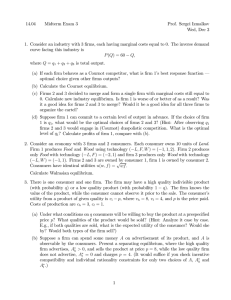

Strategist's Toolkit: Strategic Analysis & Decision Making

advertisement