Understanding Human Communication, 14e Ronald Adler, George Rodman, Athena du Pré

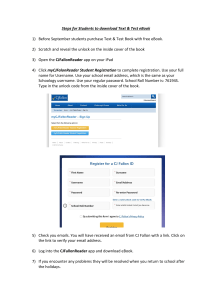

advertisement