Principles of Taxation for Business and Investment Planning, 2024 Edition By Jones, Rhoades-Catanach, Callaghan, Kubick

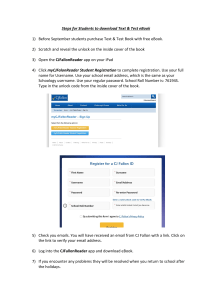

advertisement