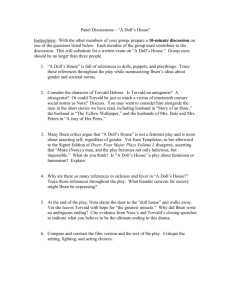

Looking closely at how weakness and strength are represented in at least two of the works you have studied, discuss the significance of the relationship between the two. The primordial archetype of the all-conquering hero posits absolute moral rigidity, overt displays of strength and abject honesty as the epitome of strength, whereas comparatively morally grey, deceitful characters are considered cowardly and weak. Henrik Ibsen’s classic realist play ‘A Doll’s House’ and Marjane Satrapi’s seminal coming of age graphic novel ‘Persepolis’ complicate normative conceptions of strength and weakness by depicting characters disoriented by an oppressive society exercising autonomy and expressing strength in manners typically considered shows of weakness. The vicissitudes endured by Nora and Marji, the protagonists, seem to indicate the underdog’s weapons by necessity differ from the victor, which Ibsen and Satrapi highlight through depictions of petty mechanics of defense, deception, a resistance to moral fixity and the necessity of existing society. Ibsen and Satrapi establish the weaknesses of their protagonists nearly the instant they are introduced, as well as, providing them with their initial, seemingly infantile symbols of covert resistance. As an undereducated, financially dependent woman repressed by the Victorian patriarchal hegemony, Nora is seemingly rendered helpless. Her husband, Torvald lavishes her with infantilizing nicknames such as ‘my helpless little mortal’, ‘squirrel’ and most frequently ‘skylark’, her association with an ornamental bird in a cage signifying that she is trapped in her role as his frivolous wife. Torvald’s power over those around him also has his financial dimension, every character in the play save Dr Rank who is dependent on his money. However, Nora has mechanisms of defense against him, ones considered laughable by the patriarchy but invaluable to women, who must be careful not to show their hand. Her womanhood isn’t merely a weakness, but can be wielded as a weapon – considering her affection of helplessness when practicing the tarantella, begging Torvald to come watch her and ‘not leave her for even a minute’ when she wants to keep him from reading Krogstad’s letter. She allows Torvald to think of her as a ‘spendthrift’ hellbent on buying petty things so she could continue paying off the loan that saved their family, hiding behind a sexist stereotype. Her symbol of resistance is a macaroon, hastily eaten against Torvald’s orders. While she may pretend she would ‘never think of going against him’, her continued consumption of this very typically feminine sweet treat hints at her iron will. In contrast to Nora, Marji seems more overtly independent and belligerent, her weakness in the face of totalitarian Islamic regime seemingly originating from her youth, her symbols of rebellion being the epitome of western adolescence, but Satrapi’s depiction of her growing into womanhood indicates that regardless of her comparative power, her gender condemns her to the same sexism that Nora endures. Marji’s childhood is marked by violence, the adults around her perpetually accosted by the puppets of the regime – her mother is assaulted and faces threat of rape, while her beloved uncle Anoosh is killed. With even the adults in her life subject to degradation, her youth renders her doubly helpless. When she is accosted by two elderly veiled women (guardians of the revolution) for wearing western clothes and Michael Jackson pin, her only form of defense is lying, eventually dissolving in tears as she concocts a story about a wicked stepmother, the drawing of her blubbering face provoking repulsion in the reader. When she smokes cigarettes and headbangs to Kim Wilde, she simultaneously resists her parents and the regime, shouting ‘Dictator! You are the guardian of the revolution in this home’, drawing a parallel between the regulating forces of her parents and the regime. But adulthood will not free her from the oppression of the regime. A panel shortly after her return to Iran depicts her form being dwarfed by murals of martyrs, staring up at them with a wary eye, the contrast in size created by spatial mechanics conveying her helplessness in the face of systemic oppression. The Iranian population’s collective voicelessness is further conveyed by the choice of not featuring speech heavy content or captions in her depiction of a raided party that led to the death of a friend. Overall, Ibsen and Satrapi highlight the fact that though their personal degrees of strength may vary, they do not diminish one’s weakness in the face of a more powerful oppressor, and that for the weak, petty symbols of defense like macaroons and cigarettes are actually vital to their exercise of autonomy. Furthermore, ‘A Doll’s House’ and ‘Persepolis’ complicate their definitions of strength and weakness by representing deception – considered cowardly – as an efficient manner of retaining a measure for power against an oppressor. ‘A Doll’s House’ presents a deception as a terrible but unavoidable sin used in the service of right. While Nora is considered a childish character, Ibsen highlights her recognition of Torvald’s inability to confront the savagery of life through his reaction to her wildly dancing the tarantella, when he complains that it is a ‘trifle too realistic’. This underpins Nora’s choice not to tell him about the true extent of his sickness, the loan, as well as the severity of Dr Rank’s illness, making deception the key to ensuring his mental wellbeing. But Ibsen suggests that in order to genuinely seize power and independence in the face of patriarchal hegemony, Nora must make a clean presentation of her actions and willfulness, fully claiming them, as evidenced by Mrs. Linde playing the part as deus ex machina by convincing Krogstad to leave his letter in the letterbox, exposing Nora, seeing it as necessary to her happiness. In contrast, ‘Persepolis’ presents lying and concealment as wholly necessary when enduring a viciously intolerant regime, and a more positive source of strength. For one, Nora is a single person resisting a domineering but non-violent husband. Marji and her family are a few of thousands of people attempting to survive imprisonment and execution, seeming to present collective deception as a public good. In order to protect themselves from prying eyes, Marji’s mother had to put up blackout curtains, indicating how the divide between public and private behaviour widens when people are not permitted to enjoy simple pleasures within their own homes. This dichotomy between public conformity masking private rebellion is further illustrated through two juxtaposed panels depicting Marji and her college mates in hijabs versus them with loose hair and makeup. When Marji and her family are accosted by teenage boys with guns who threaten to search their house for alcohol, her grandmother lies about having diabetes that isn’t presented as a necessary evil but a necessary good, permitting them to pour the alcohol away and avoid violence. While Ibsen and Satrapi vary in their moral conceptions of deception, they both identify it as necessary to minimize harm, and do not characterize it as a cowardly act, but a brave alternative to conformity. ‘A Doll’s House’ and ‘Persepolis’ make a final, powerful statement against normative conceptions of weakness and strength by redefining the weakest of acts – the retreat. In ‘A Doll’s House’, Nora’s decision to leave her home marks the beginning of selfactualisation and freedom from the shackles of patriarchal domesticity. In Ibsen’s temporal context, leaving one’s family was a horrific act, Victorian standards dismissing women who did so as the pinnacle of both emotional and moral weakness. Helmer calls upon this worldview by reminding Nora of her ‘duty’ to him and their children, suggesting that abandoning them during a period of marital difficulty would be immoral and weak. Nora confronts him by pointing out that she has a ‘more important duty’ to herself. She also posits her departure as an act of familial love – an attempt to gain the worldly knowledge and experience she requires to be a wise mother and equal partner. ‘A Doll’s House’ follows the typical structure of a three-scene play with exposition, conflict and resolution. Her departure at the end of the play signifies a solution to the personal and societal problems posed by the narrative, as well as the beginning of a new era on New Year’s day. ‘Persepolis’, being an autobiographical novel, covers a far wider swath of time, giving it the opportunity to explore elements of strength and weakness in a retreat and eventual return. In the context of modern Middle Eastern conflict and the refugee crisis, the ultimate act of freedom is generally considered the act of leaving an oppressive, war-torn nation for the freedom of safer locales. But just as Ibsen countered the norms of his period, Satrapi does the same evaluating the necessity of a retreat and the courage required to return. Marji’s decision to return to Iran after her hardships in Austria isn’t a failure as she describes it, or a final submission to the oppression of the regime, but an act of incredible strength and familial love. Her long hair is indicative of her womanhood, needing to be covered by a veil, when in Iran. Her cutting her hair – first to a bob and then to a punk crop – is symbolic of her distancing herself from war and Iran. When she finally decides to return, her hair grows out and she considers the veil a necessary compromise to see her family again, her return to conformity – an incredible act of courage and love. Even her destructive relationship with Reza – which could be perceived as her succumbing to the doctrine of a monogamous, conservative culture – is a subversive act of strength. After avoiding people in Austria on talks of war, changing news channels and even pretending to be French, she marries a former soldier, saying, “sought in him a war I had escaped.” Though she ultimately divorces him and immigrates to France, her relationship with Reza symbolizes her finally confronting the horror of her country with open eyes and heart. Overall, ‘A Doll’s House’ and ‘Persepolis’ counter the normative conceptions of retreat and return in their contexts by depicting both as potential expressions of power, selfactualisation and strength. Despite the vast variability in their protagonists and the gap in their temporal and spatial context, the two literary works present the relationship between strength and weakness as infinitely compliant through the perspective of one already weakened by society. 1678 words