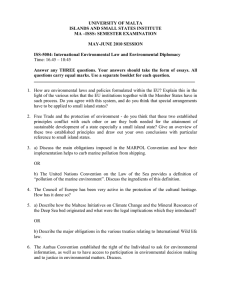

Principles of International Environmental Law by Philippe Sands

advertisement