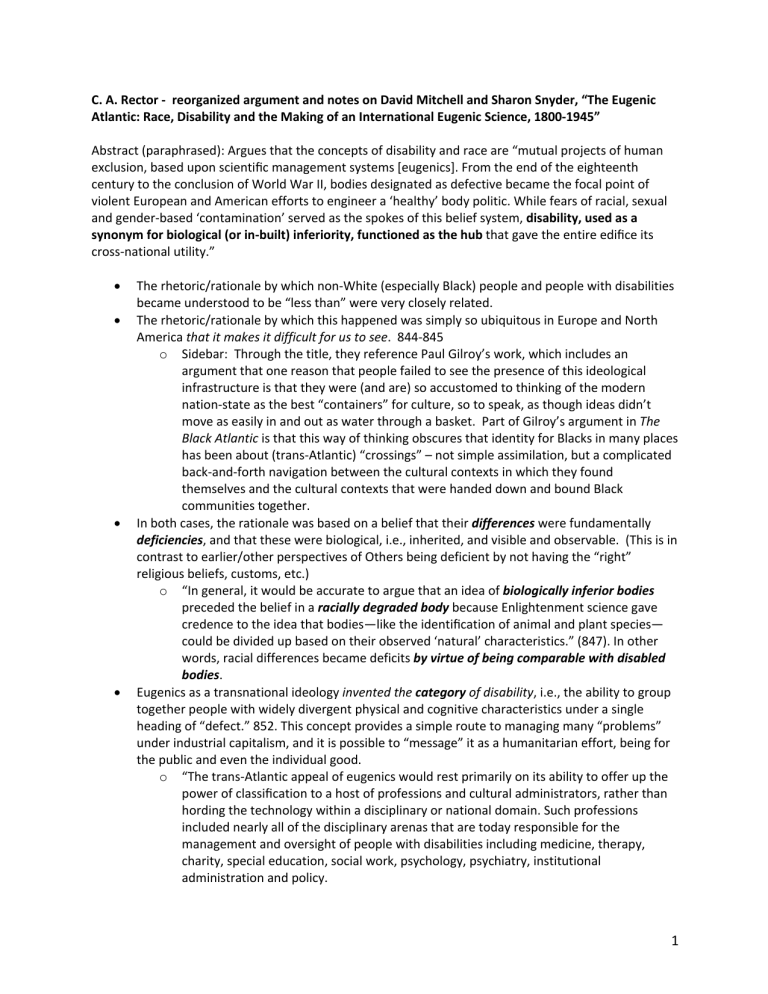

C. A. Rector - reorganized argument and notes on David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder, “The Eugenic Atlantic: Race, Disability and the Making of an International Eugenic Science, 1800-1945” Abstract (paraphrased): Argues that the concepts of disability and race are “mutual projects of human exclusion, based upon scientific management systems [eugenics]. From the end of the eighteenth century to the conclusion of World War II, bodies designated as defective became the focal point of violent European and American efforts to engineer a ‘healthy’ body politic. While fears of racial, sexual and gender-based ‘contamination’ served as the spokes of this belief system, disability, used as a synonym for biological (or in-built) inferiority, functioned as the hub that gave the entire edifice its cross-national utility.” • • • • The rhetoric/rationale by which non-White (especially Black) people and people with disabilities became understood to be “less than” were very closely related. The rhetoric/rationale by which this happened was simply so ubiquitous in Europe and North America that it makes it difficult for us to see. 844-845 o Sidebar: Through the title, they reference Paul Gilroy’s work, which includes an argument that one reason that people failed to see the presence of this ideological infrastructure is that they were (and are) so accustomed to thinking of the modern nation-state as the best “containers” for culture, so to speak, as though ideas didn’t move as easily in and out as water through a basket. Part of Gilroy’s argument in The Black Atlantic is that this way of thinking obscures that identity for Blacks in many places has been about (trans-Atlantic) “crossings” – not simple assimilation, but a complicated back-and-forth navigation between the cultural contexts in which they found themselves and the cultural contexts that were handed down and bound Black communities together. In both cases, the rationale was based on a belief that their differences were fundamentally deficiencies, and that these were biological, i.e., inherited, and visible and observable. (This is in contrast to earlier/other perspectives of Others being deficient by not having the “right” religious beliefs, customs, etc.) o “In general, it would be accurate to argue that an idea of biologically inferior bodies preceded the belief in a racially degraded body because Enlightenment science gave credence to the idea that bodies—like the identification of animal and plant species— could be divided up based on their observed ‘natural’ characteristics.” (847). In other words, racial differences became deficits by virtue of being comparable with disabled bodies. Eugenics as a transnational ideology invented the category of disability, i.e., the ability to group together people with widely divergent physical and cognitive characteristics under a single heading of “defect.” 852. This concept provides a simple route to managing many “problems” under industrial capitalism, and it is possible to “message” it as a humanitarian effort, being for the public and even the individual good. o “The trans-Atlantic appeal of eugenics would rest primarily on its ability to offer up the power of classification to a host of professions and cultural administrators, rather than hording the technology within a disciplinary or national domain. Such professions included nearly all of the disciplinary arenas that are today responsible for the management and oversight of people with disabilities including medicine, therapy, charity, special education, social work, psychology, psychiatry, institutional administration and policy. 1 The eugenics movement took the form of academic conferences, university degree programs and departments, and publications in the U.S. and Europe, which essentially provided the roadmap for the Nazi genocide of “inferior” peoples.” o Supporting industrial capitalism was typically an interest of the nation-state. Nationstates wanted people working outside the home, while caring for disabled family members may have reduced that pool of people (beyond that required for the raising of children.) Therefore institutionalization was an interest of the nation-state. 854 o A lack of familiarity bred contempt: “As familiarity [of communities and families in accommodating disability] lessened and eugenics rhetoric further debased its clientele, Eugenic Atlantic attitudes toward disability grew increasingly less tolerant of human differences.” 856 o Institutionalization provided a ready-made research population. “Beneath the guise of a liberal sentiment (care for those who could not care for themselves), eugenics took shape as an educational rescue mission for children who were seen as exhibiting signs that would make then unworthy of education (from atrophied muscles to cross-eyes to reading delays). Yet, once institutional administrators, trainers and, later, psychiatrists/psychologists recognised the institution as an ideal laboratory with a ready-made research population, institutions for the feebleminded sought to retain their charges.” 855 o “If disability robbed one of a viable life, reasoned Nazi eugenicists, then destruction was for their own benefit and that of the nation, through the alleviation of ‘suffering’ and a lessening of institutionalisation as an economic burden.” 857 Conclusion: They argue that disability is the “master trope” of human disqualification. o “The culmination of the era of the Eugenic Atlantic in the systematic extermination of disabled and racialised peoples allows for a juxtaposition of the intertwined fate of two populations that share an identification as ‘subhuman’.” 859 o “Skin pigmentation, religious practices, cultural separatism and refusals to assimilate came to be viewed by the dominant culture as signs of deterministic incapacity and therefore provided a basis for exclusion.” 859 o “Rather than sustain race and disability as separate phenomenon within the eugenics profile drawn here, we want to argue for the identification of a convergence that condemns stigmatised groupings to a shared deterministic fate. The fact that the systematic killing of Jews, Romanies and gay peoples in the Holocaust was devised in the gas chambers of the psychiatric killing hospitals provides an instructive parable for future research.” 860-61 “As one surveys eugenics literature of the period, it becomes evident that approaches to disabled people that were initially unspeakable—permanent institutionalisation, marriage laws, immigration laws, sterilisation laws and, eventually, even extermination—gradually creep into the discourse as a whispered plausibility… Once the unspeakable is spoken, to resignify African American novelist Toni Morrison’s phrase, the road is already paved for that very impossibility to become reality.” o • • 2 Discussion Questions • • • Snyder and Mitchell argue that historians have not adequately addressed the issue of eugenics as one of the “foremost ideological movements of the European and North American fin-de-siecle” because of a “persistent ambivalence in Europe and North America about the value of disabled lives.” 845 What do you think about their functional assertion that historians can’t see eugenic thinking very well because they’re still caught up in it? o In their view, historians have tended to differentiate the “euthanasia” or murder of people whose disabilities could have been “remediated” – i.e., Snyder and Mitchell are saying that other historians tend to differentiate people who could be “normalized” from those who could not, i.e., that these other historians themselves are participating in a worldview that places a greater value on people with disabilities who can be “normalized” than those who cannot. 846-847 o Existing historical scholarship tends to dismiss eugenics as a “quack science,” which lets us avoid having to deal with its lingering repercussions. What are the consequences of this? Snyder and Mitchell note that cognitive disabilities (“idiocy” or “feeblemindedness,” in the parlance of the times) were positioned at “the farthest degree of subnormality.” How does that intersect with contemporary culture? What value do we place on intelligence as a component of human value? 846 See the last point in the outline. Do you see parallels in today’s political discourse? What do you think about that? 3