Stuvia-683145-international-business-law-samenvatting-hanzehogeschoo

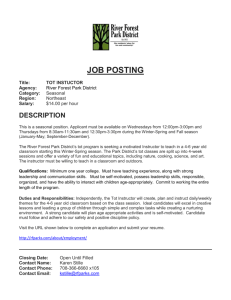

advertisement