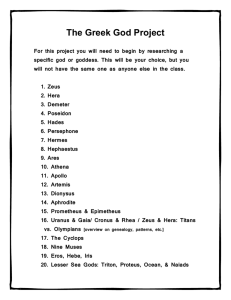

The Concept of the Goddess: Mythology & Religious Studies

advertisement