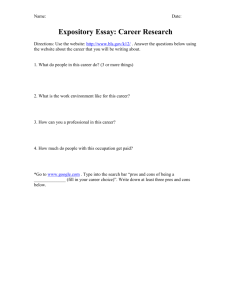

Appetite 173 (2022) 105979 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Appetite journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/appet A pilot study examining the impact of a brief health education intervention on food choices and exercise in a Latinx college student sample Julie Blow a, Roberto Sagaribay III b, Theodore V. Cooper b, * a b Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso, 5001 El Paso Drive, El Paso, TX, 79905, USA The University of Texas at El Paso, 500 West University Avenue, El Paso, TX, 79968, USA A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Keywords: Transtheoretical model Self-determination theory Intervention Eating Exercise Self-monitoring Healthy eating and physical activity (PA) necessitate interventions designed to increase these behaviors. SelfDetermination Theory (SDT) posits addressing psychological needs to promote intrinsic motivation, while the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) posits progression through stages of change consistent with contemplating pro­ cesses of change. Previous findings suggest the efficacy of combining these approaches to understand, initiate, and maintain behavior. This study assessed a pilot intervention to increase healthy eating and PA based on components derived from SDT and TTM. Latinx college students (N = 267) were randomized to either the Fit U intervention or the self-monitoring only group. The Fit U intervention augmented self-monitoring with personalized, culturally-tailored motivational enhancement feedback and goal setting. Inferential analyses used hierarchical regression models to predict total calorie intake, fruit and vegetable (FV) intake, eating behavior, PA, and perceived competence for diet and exercise. Logistic regression models were used to examine changes in motivation to engage in a healthy diet and PA at post-test. Findings suggest those in Fit U reported lower calorie intake (β = 0.143, p = .023), improvement in healthy eating (β = − 0.157, p < .001), increased perceived competence for diet (β = − 0.145, p = .007) and exercise (β = − 0.167, p = .003), and progression through the stages of change for exercise (OR = 0.297, p = .003). Findings suggest the efficacy of personalized, culturallytailored motivational enhancement and goal setting beyond simply self-monitoring on healthy eating and PA outcomes in Latinx college students. Future directions include assessing the impact of Fit U on a larger scale and including long term follow-up assessments to assess the sustainability of eating and PA changes and their impact on superordinate outcomes such as weight loss. 1. Introduction In the United States, 42.4% of adults are obese (Center for Disease Control and Prevention [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or greater, is associated with coronary heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, certain cancers, hypertension, stroke, osteoarthritis, and high cholesterol (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Obesity prevalence in Hispanic individuals (39.7%) is disproportionately higher than their White, Non-Hispanic and Asian counterparts (39.7% vs 32.2% and 12.5%), as are obesity-related diseases (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Hispanic health and health disparities are often shaped by factors such as lack of access to preventative care (i.e., health care, safe spaces for exercise, and healthy foods) and language/cultural barriers (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2021). Compared to Non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanics often have higher availability of fresh foods and a family-oriented meal pattern that serves as a protective factor against unhealthy eating (Skala Dortch et al., 2012). However, studies in the U.S. have suggested more acculturated Hispanic families eat fewer FV, less rice, drink more soda, and eat more fast food compared to less acculturated families (Creighton et al., 2012). Addi­ tionally, Hispanic families are more likely to experience food insecurity (Coleman-Jenson et al., 2021) which is associated with obesity, emotional eating, and poorer diets (Lopez-Cepero et al., 2020; Sharkey et al., 2017). The perception often reported by Hispanic individuals of regular PA includes language and family obligations as barriers and not considering PA as a health-promoting behavior (Joseph et al., 2018). Instead, PA is considered a luxurious and selfish activity. Despite these * Corresponding author. Prevention and Treatment of Clinical Health Laboratory Department of Psychology University of Texas at El Paso, 500 West University Avenue, El Paso, TX, 79968, USA. E-mail address: tvcooper@utep.edu (T.V. Cooper). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.105979 Received 1 April 2021; Received in revised form 23 February 2022; Accepted 24 February 2022 Available online 1 March 2022 0195-6663/© 2022 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. J. Blow et al. Appetite 173 (2022) 105979 greater risks for poor health, few programs have been developed, implemented, and assessed to enhance healthy eating and physical ac­ tivity in Latinx individuals; even fewer have done so within Latinx col­ lege students, the fasted growing ethnocultural minority group entering college (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). Healthy eating (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020) and physical activity (Fiuza-Luces et al., 2018) are the primary recom­ mendations to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with weight such as the prevention of chronic diseases like high blood pressure, heart disease, and Type 2 diabetes. Dietary guidelines suggest four servings of fruits, five servings of vegetables per day (American Heart Association, 2017), and 150 min of moderate intensity physical activity (PA) per week (United States Department of Health & Human Services, 2019). Only 4.3% of college students report meeting guidelines for FV intake, and approximately 45% report engaging in recommended levels of PA (American College Health Association, 2019). Similar findings were observed in a study of college students on the U.S./Mexico border (Hu et al., 2011). Just 2% of students met guidelines for FV intake; however, 63% met PA guidelines. While PA findings are promising, healthy eating may be lacking; thus, it is vital to encourage students to adopt healthier eating behaviors and maintain, and even grow, regular physical activity. Two theoretical models were utilized to conceptualize the develop­ ment of a Latinx college student healthy eating and PA intervention: Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, 2000) and the Trans­ theoretical Model (TTM; Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). SDT is a motivation-based model, purporting successful behavior change when one moves from lacking motivation, to extrinsically motivated, to intrinsically motivated. SDT posits increases in autonomy, competence, and relatedness elicit internally motivated change (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Many studies have used SDT-based weight loss, PA, and dietary behavior interventions with promising results, as these increased autonomous self-regulation, intrinsic motivation, and perceived competence relative to non-theoretical interventions (Silva et al., 2010; Trief et al., 2017). Specifically, interventions grounded in SDT suggest autonomous and intrinsic motivation as predictors for improvements in food choices, adherence to vigorous PA (Hartmann et al., 2015), and FV intake (Kaponen et al., 2019). SDT-based interventions for Latinx samples are limited, suggesting the need for assessments of novel interventions. However, one study demonstrated both cultural beliefs (i.e., destiny beliefs and familism) and SDT motivations predicted adherence to a health information text messaging intervention (Cameron et al., 2017), suggesting interventions targeting Latinx individuals should emphasize personal control and one’s ability to change. TTM is also a motivation-based model that is used to explain and predict how and when behavior change occurs (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). The theory posits behavior change involves progression through different stages (i.e., precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance); multiple processes of change such as con­ sciousness raising, helping relationships, self-reevaluation, and rein­ forcement management are suggested to increase readiness through the different stages (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). Thus, identifying an in­ dividual’s stage of change (SOC) is beneficial in determining how to intervene and the optimal processes of change (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). TTM-based weight management interventions have demon­ strated improved body perception, reduced weight and body mass index, and lower consumption of calories and foods high in fat (Johnson et al., 2013; de Menezes et al., 2015). Similarly, SOC techniques (i.e., perceived competence, self-esteem) are also related to motivational readiness to increase PA and improve nutrition (Boff et al., 2018; de Menezes et al., 2016). While interventions for improving PA and healthy eating are promising, little is known of the efficacy of TTM-based in­ terventions for diverse populations (i.e., Latinx samples). Thus, incor­ porating TTM in eating and activity based interventions and integrating culturally tailoring with Latinx college students represents an innovative approach, largely unaddressed in previous studies. Intervention studies of SDT and TTM applied to weight related changes have demonstrated efficacy, yet in some instances, it appears TTM has yielded strong results in terms of healthy eating, and SDT has demonstrated targeted PA outcomes. For example, an intervention grounded in TTM demonstrated those in the action phase reported an increase in FV intake and reductions in weight compared to those in other stages of change; however, improvement in exercise was not as successful (Karupaiah et al., 2015). Yet a recent study indicated an intervention grounded in SDT increased autonomous motivation for exercise (Donnachie et al., 2017). Given findings such as these, the combining of these two models to promote both healthy eating and regular PA may be optimal. In fact, one earlier study demonstrated Af­ rican American women were more likely to report less self-determined forms of exercise regulation in the earlier stages and more self-determined forms at the action and maintenance stages of TTM (Landry & Solmon, 2004). One more recent study of 100 university employees assessed a combined TTM/SDT group coaching intervention to enhance PA. Results indicated that after 15 weeks, participants re­ ported higher scores on multiple processes of change and self-efficacy, as well as multiple indicators of physical fitness (Bezner et al., 2020). Thus Latinx-focused weight related assessments, intervention studies high­ lighting the efficacy of each theoretical model on either healthy eating or PA, and combined intervention studies demonstrating desired out­ comes suggest the potential impact of combining these models to tailor a healthy eating and physical activity intervention in Latinx college students. With regard to the content and modality of intervention strategies, weight management interventions in young adults that included selfmonitoring and daily weighing aided in sustained weight loss (Carter et al., 2017; Goldstein et al., 2019; Patel et al., 2020), and improved adherence when accompanied with feedback (Burke et al., 2012; Hutchesson et al., 2016). Moreover, many studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of personalized feedback (i.e., dietary and physical activity recommendations) to intervention adherence and positive out­ comes (Beleigoli et al., 2020). Culturally tailored interventions related to diet and PA promotion in Hispanics have also yielded positive results (McCurley et al., 2017; Prado et al., 2020). Some have included digital or online feedback with mixed results (Chambliss et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2008), yet one study also noted a preference for interventions offered on campus as opposed to online or other physical locations (Gokee LaRose et al., 2011). However, gaps within the literature exist such that many of these studies were conducted with overweight in­ dividuals (Gokee LaRose et al., 2010), with older individuals (Johnson et al., 2008), and with limited Hispanic/Latinx representation (Johnson et al., 2008). Taken together, the development and assessment of a campus-based face to face intervention that augments self-monitoring with highly personalized, motivationally based, culturally tailored feedback and goal setting is innovative and warranted. The aims of the current study were to assess the efficacy of a healthy eating and PA intervention (Fit U) for Latinx college students. Hypoth­ eses were that the Fit U would demonstrate positive changes in primary outcomes (i.e. total calorie intake, FV intake, eating behavior, and PA) and secondary outcomes (i.e. motivation and competence to engage in a healthy diet and PA) relative to a self-monitoring group. As the pilot study was short, weight loss was not assessed. 2. Methods 2.1. Participants A power analysis for a multiple linear regression (Cohen et al., 2003) assuming 15% of variability in control variables, 2.5% for condition, and power set to 0.95 yielded a necessary sample size of 267 participants. Latinx college students (N = 267) were recruited from university psy­ chology courses. Eighty-eight percent were retained at post-test, resulting in a sample size of 235 (68% female; see Fig. 1 for Flow of Participation). Individuals of Latinx descent and/or report being 2 J. Blow et al. Appetite 173 (2022) 105979 2.2.5. Stage of change (5 a day) for FV consumption Assessed number of FV servings consumed per day (Vallis et al., 2003) and evaluated SOC (fewer than five servings = precontemplation, contemplation, preparation; five or more servings = action or maintenance). 2.2.6. wt decisional balance (WDB) A 20-item measure assessed positive and negative aspects of losing weight (O’Connell & Velicer, 1988). Responses are summed to create pros and cons. Higher scores indicate greater endorsement of positive and negative aspects of losing weight. High internal consistency was observed in the current study (α = 0.92 and α = 0.83, respectively). 2.2.7. Eating behavior inventory (EBI) A 26-item measure assessed weight loss and management behaviors (O’Neil et al., 1979). Items are summed; higher scores indicate behav­ iors conducive to weight loss. The internal reliability for the EBI was 0.67. 2.2.8. Food and activity log Participants were instructed to record the brand, description, and serving size of each food into a paper food and activity log. PA type and duration was also recorded. Total calorie intake was derived from par­ ticipants’ logs and calculated by study staff using CalorieKing.com (CalorieKingWellness Solutions, 2013). This database derives nutri­ tional content from trusted sources and is checked by dieticians. FV intake was calculated by serving sizes, and PA was calculated as number of minutes. 2.2.9. Body composition analyzer Participants’ height, weight, and body composition were measured in person without shoes by a body composition analyzer (Tanita Body Composition Analyzer - Model TBF-215). 2.2.10. Total energy expenditure (TDEE) TDEE, or daily calorie needs, were calculated using the HarrisBenedict Equation. This equation is commonly used to estimate Basal metabolic rate (BMR) based on the height, weight, sex, and age of the individual and then multiplies the derived value by an activity factor to obtain and individual’s TDEE (Harris & Benedict, 1919). BMR was ob­ tained from the body composition analyzer’s output. Fig. 1. Flow of participation. international/Mexican comprise 83% of the student body; females represent approximately 54% of undergraduates (UTEP Center for Institutional Evaluation, Research and Planning, 2020), suggesting the representativeness of the present sample (though the sample is skewed female). 2.3. Procedure The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board from the University of Texas at El Paso and was in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Students initiated appointments through a secure online database responding to a description of the eligibility criteria, which were posted online and assessed in person by researchers at the appointment time. Inclusion criteria were: 1) aged 18 or older and 2) self-report Latinx ethnicity. Exclusion criteria were: 1) currently pregnant or nursing and 2) currently participating in a formal diet and/or exercise program. During the initial appointment, the re­ searchers first conducted an eligibility screening interview by asking participants their age and ethnicity. Ineligible students were thanked and issued partial course credit. Eligible participants completed the informed consent and baseline assessments. After, participants were randomized into the self-monitoring or the Fit U group using an online random number generator. The randomization process was included in the informed consent. Interventionists were trained and supervised by the PI and provided both conditions. Each interventionist completed worksheets using participants’ responses in order to ensure fidelity. Baseline sessions lasted approximately 2 h to include consent, assess­ ments, body composition analysis, and intervention delivery. The first weekly check in lasted under an hour; timing was based largely on goal attainment, questions, and the extent to which new goals needed to be 2.2. Measures 2.2.1. Sociodemographics Demographic information and risks associated with weight, such as family/personal history of Type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, and high cholesterol, were obtained through self-report. 2.2.2. Perceived competence scale diet (PCSD) A 4-item measure assessed confidence in ability to maintain a healthy diet (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Scores are averaged; higher scores indicate greater perceived competence for diet. Internal reliability for the PCSD was .93. 2.2.3. Perceived competence scale exercise (PCSE) This measure is similar in scoring, number of items, and interpreta­ tion to the PCSD, but assessed confidence in ability to exercise regularly (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Internal reliability for the PCSE was .92. 2.2.4. Exercise stage of change: short form (ESOC) A single item measure assessed whether participants were engaged in or plan to engage in regular exercise. Responses determine SOC (Marcus et al., 1992). 3 J. Blow et al. Appetite 173 (2022) 105979 developed. The final session also lasted under an hour and included posttest assessment completion, body composition analysis, and debriefing. college students, within the present sample, doing so seemed more a necessity in order to increase activity. In addition, students noted that exercising alone seemed selfish and noted collectivistic themes regarding physical activity participation. Through highlighting benefits and reducing barriers, each participant was able to initiate a tailored activity plan to enhance activity in a manner consistent with work, ac­ ademic, and family obligations (Please see Supplementary Table 1 for intervention mapping of culturally tailored examples and themes for healthy eating and physical activity enhancement). Goals were recorded for diet and exercise for the upcoming week. Additional generic “Tips” handouts adapted from a manual for main­ taining a healthy diet and PA (Cooper & Burke, 2003) were reviewed with the participant, and these were personalized and tailored based upon their unique responses to intervention components (Please see Supplementary Material 2 for intervention worksheets and initial “Tips” handouts prior to individualized tailoring). Participants were given the same instruction in completing food and activity logs as the self-monitoring group. Goal attainment was assessed one week later at the first check-in. New goals or the continuation of current goals were outlined. A week after the first check-in, all participants had body composition measured, completed post-test assessments and were debriefed. Partic­ ipants were awarded 5 h of course credit. 2.3.1. Self-monitoring group Participants had body composition measured after completing the baseline survey to avoid affecting responses. Results were provided at the study’s completion. Participants were given instruction in completing food and activity logs, which included accurately recording various food servings (i.e. “a serving of meat is about the size and thickness of a deck of playing cards”), the manner in which the food was prepared (i.e. breaded and fried, or grilled), and minutes engaged in PA. Participants were asked to record their food and physical activity intake for a period of two weeks. 2.3.2. Fit U intervention The Fit U group was provided with body composition feedback to provide optimal data to them when taking part in other intervention components, such as goal setting. Motivation to eat a healthy diet was assessed, guided by participants’ baseline survey responses. A decisional balance exercise determined personal positive and negative aspects of a healthy diet; benefits and barriers were assessed. Decisional balance and motivational enhancement are consistent with both TTM processes such as self-reevaluation (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997) and promoting auton­ omy and competence within SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Interventionists helped participants consider components that contributed to the scale tipping in favor of maintaining a healthy diet. While traditional reasons for eating healthily were noted and emphasized (e.g., better health, control weight), culturally specific factors were also highlighted such as enhancing healthy family eating. As part of the strategies to overcome any barriers to maintaining a healthy diet, the interventionist elicited from the participant what it means to “eat healthy” and assisted in debunking any ideas that food should be boring or bland in order to be considered healthy. By using foods that the participant enjoys, this ac­ tivity utilized culturally-relevant food items, as has been found to be efficacious in previous interventions (Foreyt et al., 1991). As an exercise, favorite food items that are typically viewed as unhealthy were decon­ structed and reconstructed into a healthier version of that food. The participant was encouraged to make a list of different ways that various foods can be made healthier with a few small changes, such as utilizing low-calorie and nutritionally dense condiments, such as salsa, in place of high fat options like cheese or sour cream. This exercise also was used to address other noted, often culturally-related barriers, for example that often students are not the primary cooks in their household and thus do not have control over how the food is prepared, yet do have control over portion size, plate assembly, and condiments. There was also a strong noted desire to not offend the family member who cooks by refusing food; interventionists suggested polite refusal strategies yet also high­ lighted refusal of foods is unnecessary and emphasized learning to build a nutritionally better balanced plate. A decisional balance exercise and motivation and barriers to PA were assessed similarly. Interventionists helped participants consider com­ ponents that contribute to the scale being tipped in favor of exercising regularly. Note that throughout these activities, theoretical constructs were also integrated when possible (e.g., TTM stimulus control, SDT relatedness). Again, in addition to common benefits of physical activity increases (e.g., enhanced health), more culturally tailored strategies were emphasized such as exercising with family members and using this time to provide and receive social support. These strategies were often utilized to overcome noted barriers such as lack of time to exercise due to family, home, and work commitments. That physical activity needs to be structured and intense was debunked in favor of incorporating PA into needed daily activities (e.g., parking further and walking greater distance, taking the stairs). Further, that many students were com­ muters, and some lived across the border in Mexico, led to participants reporting safety concerns, as well as financial impediments to activity. Thus, while using University facilities for activity is an option for many 2.4. Statistical analyses Hypotheses were specified before the data were collected. All base­ line missing data were imputed prior to analyses using the hot deck imputation method (Roth, 1994). The variables used were sex, student classification, and annual income. Responses from participants who had complete data and who matched the participant with missing values on the aforementioned variables were used to impute missing values (Myers, 2011). Missing data analyses for the current dataset found that 0.29% of the values were missing. A logistic regression model was used to assess baseline differences between study completers and non-completers. Four hierarchical mul­ tiple linear regressions assessed differences between groups across pri­ mary outcome variables: total calorie intake, FV intake, PA, and healthy eating behaviors at post-test. Multicollinearity was not observed in any model. Independent variables were entered in stepwise, in which Step 1 control variables were entered (i.e., age, sex, BMI, and interventionist) and in Step 2 group condition (i.e. self-monitoring or Fit U) was entered. Two hierarchical multiple linear regressions assessed differences be­ tween groups across changes in perceived competence for diet and ex­ ercise at post-test. For these analyses, control variables were entered in Step 1 (i.e., age, sex, BMI, interventionist, baseline scores on the pros and cons scales of the WDB, and baseline scores from the PCSD or PCSE), in Step 2 condition was entered, and in Step 3 the pros and cons of losing weight at follow up were entered. Logistic regression analyses assessed motivational changes for FV intake and exercise. Change was concep­ tualized as “forward movement” or “no forward movement” between baseline and post-test assessment. Independent variables were entered in stepwise, in which Step 1 control variables were entered (i.e., age, sex, BMI, interventionist, and baseline WDB pros and cons), in Step 2 con­ dition was entered, in Step 3 post-test WDB pros and cons were entered, and in Step 4 the interaction of post-test WDB pros and cons by condition were entered. 3. Results Frequencies of sociodemographic variables, eating behaviors, and physical activity are reported in Table 1. Baseline differences between study completers and non-completers were marginally significant, χ2 (14) = 23.64, p = .051, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.17. Completers were more likely to report more minutes of weekly PA at baseline (OR = 1.01, p = .004). 4 J. Blow et al. Appetite 173 (2022) 105979 Table 1 Participant characteristics (Nbaseline = 267; Npost-test = 235). Characteristic Mean Age 20.70 Sex Female Male Classification Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior Graduate Weight Baseline Males 173.22 Females 136.47 Post-test Males 171.33 Females 137.64 BMI Baseline Males 25.69 Females 23.98 Post-test Males 25.49 Females 24.11 Smoking status Daily 5 < 10 Daily <5 Weekly Monthly No longer smoke, in past smoked at least 1 per day No longer smoke, in past smoked weekly Experimented with cigarettes Never smoked Self-reported healthy eating and physical activity Strength training (days per week) 2.16 Cardiovascular exercise (minutes per 255.78 week) Daily fruit and vegetable intake (cup 2.16 servings) Observed healthy eating and physical activity at post-test Daily calorie intake 1735.60 Cardiovascular exercise (minutes per 195.20 week) Daily fruit and vegetable intake (cup .84 servings) Type 2 diabetes history Personal Yes Family Yes Heart disease history Personal Yes Family Yes High cholesterol history Personal Yes Family Yes High blood pressure history Personal Yes Family Yes SDT Baseline PCS D (range 1–7) 4.85 PCS E (range 1–7) 5.58 Post-test PCS D (range 1–7) 4.89 PCS E (range 1–7) 5.41 SD Table 1 (continued ) Characteristic Frequency (%) TTM ESC Baseline Precontemplation Contemplation Preparation Action Maintenance ESC Post-test Precontemplation Contemplation Preparation Action Maintenance 5 A Day SoC Baseline Precontemplation Contemplation Preparation Action Maintenance 5 A Day SoC Post-test Precontemplation Contemplation Preparation Action Maintenance Baseline WDB Pros (range 10–50) WDB Cons (range 10–50) Post-test WDB Pros (range 10–50) WDB Cons (range 10–50) Eating Behavior Baseline EBI (range 26–130) Post-test EBI (range 26–130) 4.42 68.2 31.8 55.1 27.7 13.1 3.4 .7 39.11 26.43 40.67 29.48 5.07 4.32 5.25 4.41 .4 1.9 3.8 5.3 4.2 2.3 42.4 39.7 1.99 265.39 Mean SD Frequency (%) 1.5 11.6 32.2 25.5 29.2 1.3 13.7 10.3 47.9 26.9 11.1 41.1 40.0 2.3 5.3 10.9 45.0 44.0 4.1 4.9 32.87 25.63 10.24 7.65 33.49 27.33 11.55 8.16 72.18 9.78 75.07 10.92 When assessing caloric intake, sex (β = − 0.367, p < .001) and group condition (β = 0.143, p = .023) were statistically significant such that females and those in the Fit U condition reported less caloric intake (see Table 2). The models assessing FV intake and PA were not statistically significant. In the model assessing eating behaviors, sex (β = 0.105, p = .023), EBI scores at baseline (β = 0.709, p < .001), and group condition (β = − 0.157, p < .001) were significant predictors such that females, higher EBI scores, and Fit U participants reported higher EBI scores at post-test. Significant predictors of increased perceived competence for diet at post-test included: higher PCS D baseline scores (β = 0.565, p < .001), higher WDB cons at baseline (β = 0.234, p = .006), the Fit U condition (β = − 0.145, p = .007), and lower WDB cons at follow-up (β = − 0.364, p < .001). When the interaction of post-test WDB pros and cons by con­ dition were entered, the overall model was significant but incremental variance was not (see Table 2) Fit U participants reported greater perceived competence for diet at post-test relative to self-monitoring participants. Significant predictors of increased perceived competence for exercise at post-test included: higher PCS E baseline scores (β = 0.613, p < .001), higher WDB cons baseline scores (β = 0.301, p = .001), the Fit U con­ dition (β = − 0.167, p = .003), higher WDB pros scores at post-test (β = 0.250, p = .006), and lower WDB cons scores at post-test (β = − 0.285, p = .001). When the interaction of post-test WDB pros and cons by con­ dition were entered, the overall model was significant but incremental variance was not (see Table 2). Fit U participants reported greater perceived competence for exercise at post-test relative to selfmonitoring participants. Changes in motivation for increasing FV intake were assessed using the SOC (5 A Day). Greater likelihood of forward movement to increase FV intake was associated with female sex (OR = 2.731, p = .021), lesser 1.37 530.46 253.89 .85 0 43.8 .4 18.7 2.2 39.3 1.9 56.9 1.36 1.23 1.26 1.32 5 J. Blow et al. Appetite 173 (2022) 105979 Table 2 Summary of the hierarchical regressions predicting average calorie intake, eating behavior, perceived competence for diet, and perceived competence for exercise at post-test. Variable Average Calorie Intake Eating Behavior Perceived Competence for Diet Step 1 Age Sex BMI Interventionist B Interventionist C Interventionist D R2 Step 2 Age Sex BMI Interventionist B Interventionist C Interventionist D Condition R2 ΔR2 Step 1 Age Sex BMI EBI Baseline Interventionist B Interventionist C Interventionist D R2 Step 2 Age Sex BMI EBI Baseline Interventionist B Interventionist C Interventionist D Condition R2 ΔR2 Step 1 Age Sex BMI PCS D Baseline WDB Pros Baseline WDB Cons Baseline Interventionist B Interventionist C Interventionist D R2 Step 2 Age Sex BMI PCS D Baseline WDB Pros Baseline WDB Cons Baseline Interventionist B Interventionist C Interventionist D Condition R2 ΔR2 Step 3 Age Sex BMI PCS D Baseline B SE B β − 1.745 − 410.985 − 10.082 43.858 − 83.064 − 105.815 7.619 72.843 7.417 87.531 87.747 95.569 -.015 -.355** -.089 .034 -.064 -.075 − 2.363 − 425.571 − 7.526 − 96.328 37.018 − 75.275 151.358 7.553 72.454 7.433 86.778 87.006 94.781 66.265 -.020 -.367** -.067 -.068 .029 -.058 .143* .018 2.171 .197 .769 -.619 − 1.119 -.277 .112 1.107 .109 .051 1.289 1.278 1.471 .008 .092 .086 .706** -.024 -.043 -.009 .031 2.470 .143 .772 -.507 − 1.393 -.650 − 3.429 .110 1.083 .107 .050 1.257 1.249 1.438 .965 .013 .105* .062 .709** -.021 -.019 -.053 -.157** .014 -.152 -.005 .489 .023 .016 .159 .017 .053 .008 .050 -.055 -.018 .523** .189* -.008 .009 -.052 .073 .259 .400 .180 .178 .202 .024 .086 .114* .014 -.103 -.009 .511 .021 .015 .159 .017 .053 .008 .052 -.038 -.035 .546** .177* -.010 .009 -.063 .091 .231 .361 -.347 .178 .177 .200 .139 .030 .076 .103 -.137* .015 -.157 -.017 .528 .015 .152 .016 .052 .054 -.057 -.063 .565** Table 2 (continued ) .135** .155** .020* .541** Perceived Competence for Exercise .563** .024** .382** .399** .017* Variable B SE B β WDB Pros Baseline WDB Cons Baseline Interventionist B Interventionist C Interventionist D Condition WDB Pros Posttest WDB Cons Posttest R2 ΔR2 Step 4 Age Sex BMI PCS D Baseline WDB Pros Baseline WDB Cons Baseline Interventionist B Interventionist C Interventionist D Condition WDB Pros Posttest WDB Cons Posttest WDB Pros Posttest by Condition WDB Cons Posttest by Condition R2 ΔR2 .002 .012 .014 .038 .014 .234* .092 .179 .368 -.368 .020 .170 .171 .191 .135 .010 .030 .059 .105 -.145* .183* -.056 .012 -.364** Step 1 Age Sex BMI PCS E Baseline WDB Pros Baseline WDB Cons Baseline Interventionist B Interventionist C Interventionist D R2 Step 2 Age Sex BMI PCS E Baseline WDB Pros Baseline WDB Cons Baseline Interventionist B Interventionist C Interventionist D Condition R2 ΔR2 Step 3 Age Sex BMI PCS E Baseline WDB Pros Baseline WDB Cons Baseline Interventionist B .456** .057** .015 -.151 -.016 .526 .000 .015 .153 .016 .052 .012 .053 -.055 -.061 .563** -.001 .039 .014 .238* .087 .181 .369 -.548 .011 .171 .171 .192 .555 .018 .028 .060 .105 -.217 .100 -.054 .027 -.350* .007 .012 .126 -.002 .016 -.030 .457** .001 -.014 -.194 .017 .612 .007 .017 .173 .018 .061 .008 -.050 -.068 .060 .566** .054 .013 .010 .078 -.088 .209 .369 .192 .190 .217 -.028 .066 .100 -.013 -.121 .011 .638 .006 .016 .171 .018 .060 .008 -.046 -.042 .039 .589** .044 .010 .010 .060 -.071 .180 .324 -.453 .189 .187 .214 .147 -.022 .057 .088 -.171* -.012 -.156 .005 .664 -.021 .016 .166 .017 .059 .012 -.041 -.054 .017 .613** -.168 .051 .015 .301* -.066 .183 .348** .375** .027* -.020 (continued on next page) 6 J. Blow et al. Appetite 173 (2022) 105979 vegetables used as toppings, condiments, or ingredients toward total servings (i.e. fruit in yogurt parfaits, vegetables in sandwiches, and fruits or vegetables in smoothies). Even with this methodology, post-test logs yielded an average of less than one cup per day for the sample. It should be noted that while the intervention focused on improving healthy eating, due to the highly tailored nature of the intervention, it seemed that participants were more concerned with respect for familial and cultural expectations and did not focus on healthy eating as increasing fruit and vegetable intake. Given the benefits derived from consuming the recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables daily (Toh et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021), it is imperative to refine the current inter­ vention in order to improve fruit and vegetable intake in this group. Given that feedback regarding daily calorie needs was efficacious in reducing overall calorie intake in the Fit U condition, perhaps a similar health education component that outlines recommended daily servings of fruits and vegetables should be incorporated into future iterations. One previous study found that awareness of recommended daily serv­ ings of fruits and vegetables was associated with a greater likelihood of consuming the recommended amount (Erinosho et al., 2012). Moreover, efficacy may be further bolstered by eliciting strategies to incorporate more fruits and vegetables into participants’ current diets. For example, adding fruit to oatmeal or cereal at breakfast or vegetables to sand­ wiches at lunch can assist in achieving daily recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables. Table 2 (continued ) Variable B SE B β Interventionist C Interventionist D Condition WDB Pros Posttest WDB Cons Posttest R2 ΔR2 Step 4 Age Sex BMI PCS E Baseline WDB Pros Baseline WDB Cons Baseline Interventionist B Interventionist C Interventionist D Condition WDB Pros Posttest WDB Cons Posttest WDB Pros Posttest by Condition WDB Cons Posttest by Condition R2 ΔR2 .114 .342 -.441 .028 .182 .207 .145 .010 .036 .093 -.167* .250* -.046 .013 -.285* .420** .045** -.012 -.153 .005 .659 -.023 .016 .167 .017 .060 .013 -.042 -.053 .019 .609** -.181 .051 .015 .304* -.070 .116 .341 -.739 .019 .184 .183 .208 .601 .019 -.022 -.037 .093 -.279 .167 -.050 .029 -.311 .007 .013 .122 .002 .018 .028 4.3. Physical activity Increased PA was also not associated with Fit U. Weekly PA, both self-reported at baseline and derived from logs at post-test, were wellabove the recommended amount for the sample (United States Depart­ ment of Health & Human Services, 2019). Hu et al. (2011) also observed high rates of exercise in a similar sample. A ceiling effect may account for the lack of change in PA from baseline to post-test. Analyses indi­ cated those lost to post-test reported fewer minutes of baseline PA per week, suggesting those who remained were exercising the most. Future studies may wish to focus retention efforts on those who report lower levels of PA initially. .421** .001 Note: * all values significant at the 0.05 level. ** all values significant at the 0.001 level. endorsement of the pros of weight loss at baseline (OR = 0.949, p = .009), Interventionist C (OR = 2.725, p = .022), and Interventionist D (OR = 3.012, p = .025). In later steps, no other additional variables were significant (see Table 3). Changes in PA motivation were assessed using the ESOC. Increased likelihood of forward movement in ESOC was associated with Fit U (OR = 0.297, p = .003) and higher post-test WDB pros (OR = 1.135, p = .010). In later steps, no other additional variables were significant (see Table 3). Fit U participants reported greater PA motivation relative to self-monitoring participants. Data (Blow & Cooper, 2020) are available through fig­ share:10.6084/m9.figshare.12730712. 4.4. Eating behavior That females were more likely to report improvement in healthy eating behaviors at post-test suggests females may be more amenable to making healthy eating changes relative to their male counterparts. One possible explanation may be that females in Latinx cultures contribute more to food purchase and preparation (McVey et al., 2020) and were thus more sensitive to the nuances of healthy eating processed through Fit U relative to males. As predicted, improvement in healthy eating behaviors was associated with Fit U, indicating the EBI was more sen­ sitive to capturing such changes. Rather than focusing on fruit and vegetable intake, the EBI focuses on behaviors such as regulating the quantity of food or the place that food is consumed (at the table versus while reading, or watching TV), and this mirrors aspects of the Fit U intervention. Cultural emphases on addressing food quantity, healthy alternatives for enjoyed recipes (e.g., use of corn tortillas), and using time away from home to eat healthily with greater portion control may have contributed to the efficacy of Fit U in healthy eating. It is also promising that general healthy eating behavior change occurred, as one recent study found that improvement in one area increases the odds of improving in other areas (Johnson et al., 2013), though these effects were observed over longer follow-up periods. Perhaps changes in eating behavior may act as a catalyst to changes in fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity over time. 4. Discussion 4.1. Calorie intake Consistent with hypotheses, those in Fit U reported lower calorie intake relative to those in the self-monitoring group. Though restricting calories was not instructed, perhaps those in Fit U made healthier choices due to the highly personalized and culturally sensitive feedback (i.e., portion control, healthier substitutions in recipes, and daily calorie needs) and the motivational enhancement exercise. These findings show promise, as previous studies suggest even a small calorie deficit can be beneficial (Romeijn et al., 2020). Interventions with longer follow-ups are needed to assess whether these changes are maintained. 4.2. Fruit and vegetable intake Increased FV intake was not associated with Fit U participation. In line with suggestions from Hu et al. (2011) and the USDA (2020, pp. 2020–2025), researchers in the current study counted items such as salsas, agua frescas, and fruit and vegetable juices, as well as fruits and 4.5. Perceived competence for diet Increased perceived competence for diet at post-test was associated 7 J. Blow et al. Appetite 173 (2022) 105979 Table 3 Summary of the Logistic Regressions Predicting 5 A day Stage of Change Movement and Exercise Stage of Change Movement. Variables B SE B Odds Ratio Confidence Interval (CI) p 5 A Day Stage of Change Movement Step 1 Age .032 .035 1.033 .964–1.107 .360 Sex 1.005 .435 2.731 1.165–6.403 .021 BMI .042 .043 1.043 .958–1.135 .333 WDB Pros Baseline -.052 .020 .949 .913–.987 .009 WDB Cons Baseline .010 .024 .1.011 .964–1.059 .661 Interventionist B .392 .449 1.479 .614–3.564 .383 Interventionist C 1.002 .438 2.725 1.155–6.427 .022 Interventionist D 1.103 .492 3.012 1.147–7.907 .025 Step 2 Age .032 .035 1.033 .963–1.107 .364 Sex .993 .437 2.699 1.147–6.351 .023 BMI .043 .044 1.044 .959–1.137 .318 WDB Pros Baseline -.052 .020 .949 .913–.987 .009 WDB Cons Baseline .012 .024 1.012 .965–1.061 .627 Interventionist B .390 .449 1.477 .613–3.559 .385 Interventionist C 1.014 .439 2.757 1.165–6.525 .021 Interventionist D 1.119 .495 3.061 1.160–8.076 .024 Condition .123 .342 1.131 .579–2.209 .718 Step 3 Age .037 .036 1.307 .967–1.112 .304 Sex 1.047 .445 2.849 1.190–6.818 .019 BMI .052 .045 1.054 .965–1.150 .245 WDB Pros Baseline -.085 .030 .919 .866–.974 .005 WDB Cons Baseline -.026 .037 .975 .907–1.047 .482 Interventionist B .396 .457 3.115 .607–3.638 .385 Interventionist C .916 .452 1.486 1.031–6.060 .043 Interventionist D 1.136 .504 2.500 1.161–8.356 .024 Condition .314 .356 1.369 .681–2.754 .378 WDB Pros Post-test .039 .024 1.040 .992–1.090 .106 WDB Cons Post-test .055 .033 1.057 .990–1.129 .097 Step 4 Age .036 .036 1.037 .967–1.112 .308 Sex 1.078 .450 2.938 1.216–7.099 .017 BMI .055 .045 1.057 .967–1.155 .220 WDB Pros Baseline -.093 .032 .911 .856–.969 .003 WDB Cons Baseline -.022 .037 .979 .910–1.052 .560 Interventionist B .372 .458 1.451 .591–3.564 .417 Interventionist C .927 .453 2.528 1.041–6.139 .041 Interventionist D 1.148 .505 3.153 1.171–8.490 .023 Condition -.131 1.622 .877 .037–21.051 .935 WDB Pros Post-test .009 .044 1.009 .926–1.101 .833 WDB Cons Post-test .070 .077 1.073 .922–1.248 .363 WDB Pros Post-test by Condition .025 .032 1.026 .963–1.092 .427 WDB Cons Post-test by Condition -.013 .046 .987 .902–1.081 .781 2 Note: Step 1 χ2 (8) = 17.174, p = .028, Nagelkerke R = .117; Step 2 χ2 (9) = 17.304, p = .044, Nagelkerke R2 = .118; Step 3 χ2 (11) = 24.109, p = .012, Nagelkerke R2 = .162; Step 4 χ2 (13) = 24.773, p = .025, Nagelkerke R2 = .166 Exercise Stage of Change Movement Step 1 Age Sex BMI WDB Pros Baseline WDB Cons Baseline Interventionist B Interventionist C Interventionist D Step 2 Age Sex BMI WDB Pros Baseline WDB Cons Baseline Interventionist B Interventionist C Interventionist D Condition Step 3 Age Sex BMI WDB Pros Baseline WDB Cons Baseline Interventionist B Interventionist C -.024 -.123 -.002 .024 .006 -.195 -.323 .484 .035 .466 .045 .021 .025 .448 .478 .559 .976 .885 .998 1.024 1.006 .823 .724 1.622 .911–1.046 .355–2.207 .913–1.090 .983–1.067 .959–1.056 .342–1.978 .284–1.847 .542–4.854 .490 .793 .957 .251 .809 .663 .499 .387 -.024 .093 -.025 .028 -.002 -.253 -.465 .373 − 1.475 .037 .499 .049 .022 .026 .476 .513 .594 .389 .976 1.097 .975 1.028 .998 .776 .628 1.453 .229 .907–1.049 .413–2.919 .885–1.074 .984–1.074 .948–1.051 .306–1.972 .230–1.717 .453–4.657 .107–.490 .509 .852 .608 .216 .943 .595 .365 .530 .000 -.019 -.037 -.036 -.087 .057 -.241 -.636 .037 .517 .052 .049 .045 .490 .533 .981 .964 .964 .916 1.059 .786 .529 .912–1.055 .350–2.656 .871–1.067 .832–1.009 .970–1.156 .301–2.054 .186–1.506 .605 .943 .482 .076 .203 .623 .233 (continued on next page) 8 J. Blow et al. Appetite 173 (2022) 105979 Table 3 (continued ) Variables B SE B Odds Ratio Confidence Interval (CI) p Interventionist D Condition WDB Pros Post-test WDB Cons Post-test Step 4 Age Sex BMI WDB Pros Baseline WDB Cons Baseline Interventionist B Interventionist C Interventionist D Condition WDB Pros Post-test WDB Cons Post-test WDB Pros Post-test by Condition WDB Cons Post-test by Condition .443 − 1.215 .127 -.065 .615 .408 .050 .042 1.557 .297 1.135 .937 .467–5.195 .133–.660 1.030–1.251 .864–1.017 .471 .003 .010 .122 -.019 -.011 -.033 -.084 .056 -.204 -.601 .459 − 2.847 .106 -.139 .009 .047 .037 .527 .052 .049 .045 .493 .537 .624 1.998 .089 .090 .042 .050 .981 .989 .968 .919 1.057 .816 .548 1.582 .058 1.112 .870 1.009 1.048 .912–1.055 .352–2.776 .874–1.072 .834–1.013 .968–1.155 .311–2.143 .191–1.571 .465–5.378 .001–2.914 .934–1.324 .730–1.038 .929–1.096 .951–1.156 .612 .983 .529 .088 .218 .697 .263 .462 .154 .231 .122 .824 .343 Note: Step 1 χ2 (8) = 3.951, p = .862, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.039; Step 2 χ2 (9) = 19.560, p = .021, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.181; Step 3 χ2 (11) = 27.792, p = .003, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.250; Step 4 χ2 (13) = 28.769, p = .007, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.258. with Fit U. Similar findings were observed in a SDT-based intervention relative to health education (Robbins et al., 2018). It appears processing and overcoming healthy diet barriers in a culturally tailored manner (i. e., focusing on respectful refusal and appreciation strategies with fam­ ily) bolstered perceived competence for diet and post-test EBI. Increased perceived competence for diet at post-test was associated with endorsing more cons of losing weight at baseline and fewer at posttest. Consistent with SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2000) enhancing dieting self-efficacy appears to have reduced the number of negative aspects of weight loss endorsed. Extending this finding to promoting weight loss autonomy and utilizing a longer follow-up that permits measuring weight loss is a necessary future direction. for increasing FV intake, the intervention clearly was not efficacious in moving individuals into the preparation or action stages. Adding behavioral, action oriented strategies, above and beyond goal setting, to the Fit U intervention may promote later stage movement. Also, Fit U focused on general healthy eating behavior and did not specifically target FV intake; thus, future iterations should be refined to bolster motivation to increase FV intake. 4.8. Exercise stage of change movement Movement through SOC for exercise was associated with Fit U. Almost one-third of the sample was in preparation stage for exercise at baseline. As previously mentioned, Fit U participants increased perceived competence for exercise, which may have translated to moving participants into the action stage. Studies in college student (Ersoz & Eklund, 2016) and Mexican (Zamarripa et al., 2018) samples have suggested more self-determined motivations and regulations (i.e., intrinsic) are associated with the later stages of change for exercise. Many participants in Fit U reported time constraints as a barrier. Elic­ iting PA time management and coupling this strategy with culturally relevant suggestions such as exercising with family may have bolstered likelihood to engage, thereby enhancing motivation. Forward move­ ment through the stages for exercise was also associated with endorsing the pros of weight loss at post-test. It may be increasing beliefs in the benefits of losing weight enhances motivation to engage in behaviors, such as PA. 4.6. Perceived competence for exercise Consistent with hypotheses and research of SDT-based interventions (Robbins et al., 2018), forward movement in PA perceived competence was associated with Fit U. Discussing barriers and strategies was effi­ cacious in boosting perceived competence for exercise.Many of these focused on integrating other family members into PA, while others focused on minimizing discomfort with engaging in PA alone. Safety concerns while engaging in PA alone in participants’ neighborhoods were also cited as a barrier to PA. Interventionists explored feasibly safety strategies with these participants. Other strategies focused on garnering social support for PA from friends and involving them in regularly scheduled PA in order to bolster consistency, which was reportedly a barrier to PA. Increases at post-test were associated with endorsing more cons of losing weight at baseline, fewer cons at post-test, and endorsing more pros to weight loss at post-test. Promoting PA competence appears to have reduced the negative aspects of weight loss while increasing the positive aspects. 4.9. Strengths and limitations Strengths of the study are the inclusion of normal-weight individuals, minimal missing data and rates of attrition, utilizing an intervention with theoretically derived components, the addressing and inclusion of a traditionally underrepresented sample, and the use of a pilot trial that can inform the development of larger scale interventions in Latinx col­ lege students. Additionally, the study contributes to the understanding of SDT and TTM approaches with diverse samples and the effectiveness of interventions grounded in them. More studies assessing SDT and TTM components with Latinx and other ethnoculturally diverse samples are warranted. Limitations included using a convenience sample and short time to post-test, which may have limited generalizability and removed the capacity to assess weight changes. Self-reported data may have resulted in inaccurate estimates of caloric, FV, and PA intake at baseline, yet this is not likely to differ based on group nor distort changes over time. The focus on general healthy eating in the intervention did not target FV 4.7. 5 A day stage of change movement Forward movement through the SOC for increasing FV intake was associated with identifying as female and reporting fewer pros of weight loss at baseline. While completing the food log may have heightened awareness of FV intake and increased motivation to increase intake, it may not have translated to behavior change due to the short amount of time between baseline and post-test assessments. Indeed, discussing dietary benefits and barriers during the Fit U intervention did not yield movement through SOC for increasing FV intake. Previous research has suggested reporting fewer healthy eating behaviors at baseline is asso­ ciated with less forward movement with the stages of change (Brick et al., 2019). Since 41.1% of the sample were in the contemplation stage 9 Appetite 173 (2022) 105979 J. Blow et al. intake and perhaps did not prepare participants to make changes to FV intake. The intervention should be refined and bolster its efficacy for enhancing motivation to increase FV intake. Lastly, although the inter­ vention and control groups differed significantly on multiple outcomes, investigating the unique role of culturally tailored feedback could not be assessed. Future iterations should compare interventions that only differ in the type of tailored feedback provided for the participants (i.e., culturally tailored versus general feedback) to identify the relative ef­ ficacy of cultural tailoring in Latinx groups. Unhealthy weight control behaviors should also be assessed in future studies for potential threats to participants’ health. Prevention and Treatment in Clinical Health Lab at UTEP, United States, particularly Erica Landrau-Cribbs, Nicole Kim, Dessaray Gorbett, and Theo Adams. Appendix A. Supplementary data Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi. org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.105979. References American College Health Association. (2019). National college health assessment spring 2008 reference group data report (abridged). The American College Health Association, Journal of American College Health, 57, 477–488. https://doi.org/10.3200/ JACH.57.5.477-488 American Heart Association. (2017, June). Fruits and vegetables serving sizes. https ://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/add-color/fruits-and-veget ables-serving-sizes. Beleigoli, A., Andrade, A. Q., Diniz, M. D., & Ribeiro, A. L. (2020). Personalized webbased weight loss behavior change program with and without dietitian online coaching for adults with overweight and obesity: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(11). https://doi.org/10.2196/17494 Bezner, J. R., Franklin, K. A., Lloyd, L. K., & Crixell, S. H. (2020). Effect of group health behaviour change coaching on psychosocial constructs associated with physical activity among university employees. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(1), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197x.2018.1462232 Blow, J., & Cooper, T. V. (2020). Fit U data. Figshare. https://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.fig share.12730712. Boff, R., Dornelles, M. A., Feoli, A. M., Gustavo, A., & Oliveira, M. (2018). Transtheoretical model for change in obese adolescents: Merc Randomized Clinical trial. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(13–14), 2272–2285. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1359105318793189 Brick, L. A. D., Yang, S., Harlow, L. L., Redding, C. A., & Prochaska, J. O. (2019). Longitudinal analysis of intervention effects on temptations and stages of change for dietary fat using parallel process latent growth modeling. Journal of Health Psychology, 24(5), 572–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316679723 Burke, L. E., Styn, M. A., Sereika, S. M., Conroy, M. B., Ye, L., Glanz, K., … Ewing, L. J. (2012). Using mHealth technology to enhance self-monitoring for weight loss. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43(1), 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. amepre.2012.03.016 CalorieKing Wellness Solutions. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.calorieking.com/. Cameron, L. D., Durazo, A., Ramírez, A. S., Corona, R., Ultreras, M., & Piva, S. (2017). Cultural and linguistic adaptation of a healthy diet text message intervention for Hispanic adults living in the United States. Journal of Health Communication, 22(3), 262–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2016.1276985 Carter, M. C., Burley, V. J., & Cade, J. E. (2017). Weight loss associated with different patterns of self-monitoring using the mobile phone app My Meal Mate. JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.4520 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Adult obesity prevalence maps. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved October 28, 2021, from https://www. cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html. Chambliss, H. O., Huber, R. C., Finley, C. E., McDoniel, S. O., Kitzman-Ulrich, H., & Wilkinson, W. J. (2011). Computerized self-monitoring and technology-assisted feedback for weight loss with and without an enhanced behavioral component. Patient Education and Counseling, 85, 375–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. pec.2010.12.024 Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/ correlation analysis for behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Hillsdale: Erlbaum. Coleman-Jenson, A., Rabbitt, M. P., Gregory, C. A., & Singh, A. (2021). Household food security in the United States in 2020. U.S. Department of Agriculture: Economic Research Service. Retrieved February 10, 2022, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/pub lications/pub-details/?pubid=102075. Cooper, T. V., & Burke, R. (2003). Tobacco cessation clinic: Training manual. G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Creighton, M. J., Goldman, N., Pebley, A. R., & Chung, C. Y. (2012). Durational and generational differences in Mexican immigrant obesity: Is acculturation the explanation? Social Science & Medicine, 75(2), 300–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. socscimed.2012.03.013 Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum. Donnachie, C., Wyke, S., Mutrie, N., & Hunt, K. (2017). “It”s like a personal motivator that you carried around wi’ you’: Utilising self-determination theory to understand men’s experiences of using pedometers to increase physical activity in a weight management programme. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0505-z Erinosho, T. O., Moser, R. P., Oh, A. Y., Nebeling, L. C., & Yaroch, A. L. (2012). Awareness of the Fruits and Veggies—more Matters campaign, knowledge of the fruit and vegetable recommendation, and fruit and vegetable intake of adults in the 2007 Food Attitudes and Behaviors (FAB) Survey. Appetite, 59, 155–160. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.04.010 Ersöz, G., & Eklund, R. C. (2016). Behavioral regulations and dispositional flow in exercise among American college students relative to stages of change and gender. 4.10. Conclusions and future directions Findings suggest the efficacy of a brief pilot intervention for Latinx college students in reducing caloric intake, improving healthy eating, increasing perceived competence for diet and exercise, and motivating progression through SOC for exercise. Clinical implications include the importance of motivation in promoting healthy eating, the use of personalized and culturally tailored data from participants within the intervention, and the importance of goal setting to optimize success. Implications for future research include longer term follow-up assess­ ments, greater emphasis on fruit and vegetable intake, assessing the efficacy of culturally tailored feedback relative to more generic feed­ back, and the retention of those reporting lower levels of initial physical activity. Further, given Latinx college students’ high rates of smartphone and social media use (Lerma et al., 2021), adapting self-monitoring and intervention elements to digital platforms may promote heightened participant convenience and greater reach. Finally such efforts should also include the assessments of unhealthy eating behaviors and weight loss goals and outcomes to ultimately promote Latinx college student health. Contributors Blow: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investi­ gation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft Sagaribay: Writing –review and editing Cooper: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Formal analysis, Writing – re­ view and editing, Supervision. All authors significantly contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript and have given approval of submission of their work for consideration of publication in Appetite. Role of funding source No specific grants were sought from funding agencies in the public, commercial, and not-for-profit sectors for this research. Ethical statement The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board from the University of Texas at El Paso and was in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Eligible participants completed the informed consent process before proceeding to the baseline assessments. Declaration of competing interest The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge all members of the 10 J. Blow et al. Appetite 173 (2022) 105979 Journal of American College Health, 65(2), 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 07448481.2016.1239203 Fiuza-Luces, C., Santos-Lozano, A., Joyner, M., Carrera-Bastos, P., Picazo, O., Zugaza, J. L., Izquierdo, M., Ruilope, L. M., & Lucia, A. (2018). Exercise benefits in cardiovascular disease: Beyond attenuation of traditional risk factors. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 15(12), 731–743. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-018-0065-1 Foreyt, J. P., Ramirez, A. G., & Cousins, J. H. (1991). Cuidando El corazon- a weightreduction intervention for Mexican-Americans. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 53, 1639S-41S. Retrieved from http://www.ajcn.org/content/vol53/issue6/index. dtl. Gokee LaRose, J., Gorin, A. A., Clarke, M. M., & Wing, R. R. (2011). Beliefs about weight gain among young adults. Potential challenges to prevention. Obesity, 19, 1901–1904. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.203 Gokee LaRose, J., Tate, D. F., Gorin, A. A., & Wing, R. R. (2010). Preventing weight gain in young adults: A randomized controlled pilot study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 39, 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.011 Goldstein, S. P., Goldstein, C. M., Bond, D. S., Raynor, H. A., Wing, R. R., & Thomas, J. G. (2019). Associations between self-monitoring and weight change in behavioral weight loss interventions. Health Psychology, 38(12), 1128–1136. https://doi.org/ 10.1037/hea0000800 Harris, J. A., & Benedict, F. G. (1919). A biometric study of basal metabolism in man. Washington DC: Carnegie Institution. Hartmann, C., Dohle, S., & Siegrist, M. (2015). A self-determination theory approach to adults’ healthy body weight motivation: A longitudinal study focussing on food choices and recreational physical activity. Psychology and Health, 30(8), 924–948. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2015.1006223 Hu, D., Taylor, T., Blow, J., & Cooper, T. V. (2011). Multiple health behaviors: Patterns and correlates of diet and exercise in a Hispanic college sample. Eating Behaviors, 12, 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.07.009 Hutchesson, M. J., Tan, C. Y., Morgan, P., Callister, R., & Collins, C. (2016). Enhancement of self-monitoring in a web-based weight loss program by extra individualized feedback and reminders: Randomized trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18 (4), 82. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4100 Johnson, S. S., Paiva, A. L., Cummins, C. O., Johnson, J. L., Dyment, S. J., Wright, J. A., Prochaska, J. O., Prochaska, J. M., & Sherman, K. (2008). Transtheoretical modelbased multiple behavior intervention for weight management: Effectiveness on a population basis. Preventive Medicine, 46(3), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ypmed.2007.09.010 Johnson, S. S., Paiva, A. L., Mauriello, L., Prochaska, J. O., Redding, C., & Velicer, W. F. (2013). Coaction in multiple behavior change interventions: Consistency across multiple studies on weight management and obesity prevention. Health Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034215 Joseph, N. M., Ramaswamy, P., & Wang, J. (2018). Cultural factors associated with physical activity among U.S. adults: An integrative review. Applied Nursing Research, 42, 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2018.06.006 Karupaiah, T., Wong, K., Chinna, K., Arasu, K., & Chee, W. S. (2015). Metering selfreported adherence to clinical outcomes in Malaysian patients with hypertension. Health Education & Behavior, 42(3), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1090198114558588 Koponen, A. M., Simonsen, N., & Suominen, S. (2019). How to promote fruits, vegetables, and berries intake among patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care? A self-determination theory perspective. Health Psychology Open, 6(1). https://doi. org/10.1177/2055102919854977, 205510291985497. Landry, J. B., & Solmon, M. A. (2004). African American Women’s self-determination across the stages of change for exercise. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 26(3), 457–469. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.26.3.457 Lerma, M., Marquez, C., Sandoval, K., & Cooper, T. V. (2021). Psychosocial correlates of excessive social media use in a Hispanic college sample. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(11), 722–728. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0498 Lopez-Cepero, A., Frisard, C., Lemon, S., & Rosal, M. (2020). Emotional eating partially mediates the relationship between food insecurity and obesity in Latina women residing in the Northeast U.S. Current Developments in Nutrition, 4(Supplement_2). https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzaa043_081, 230–230. Marcus, B. H., Selby, V. C., Niaura, R. S., & Rossi, J. S. (1992). Self-efficacy and the stages of exercise behavior change. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport, 63, 60–66. Retrieved from http://www.aahperd.org/rc/publications/rqes/. McCurley, J. L., Fortmann, A. L., Gutierrez, A. P., Gonzalez, P., Euyoque, J., Clark, T., Preciado, J., Ahmad, A., Philis-Tsimikas, A., & Gallo, L. C. (2017). Pilot test of a culturally appropriate diabetes prevention intervention for at-risk Latina women. The Diabetes Educator, 43(6), 631–640. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0145721717738020 McVey, B. A., Lopez, R., & Padilla, B. I. (2020). Evidence-based approach to healthy food choices for Hispanic women. Hispanic Health Care International, 19(1), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540415320921471 Menezes, M. C., Bedeschi, L. B., Santos, L. C., & Lopes, A. C. S. (2016). Interventions directed at eating habits and physical activity using the transtheoretical model: A systematic review. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 33(5). https://doi.org/10.20960/nh.586 Menezes, M. C., Mingoti, S. A., Cardoso, C. S., de Mendonça, R., & Lopes, A. C. (2015). Intervention based on transtheoretical model promotes anthropometric and nutritional improvements — a randomized controlled trial. Eating Behaviors, 17, 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.12.007 Myers, T. A. (2011). Goodbye listwise deletion: Presenting hotdeck imputation as an easy and effective tool for handling missing data. Communication Methods and Measures, 5, 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2011.624490 O’Connell, D., & Velicer, W. F. (1988). A decisional balance measure for weight loss. International Journal of the Addictions, 23, 729–750. https://doi.org/10.3109/ 10826088809058836 O’Neil, P. M., Currey, H. S., Hirsch, A. A., Malcolm, R. J., Sexauer, J. D., Riddle, F. E., & Taylor, C. I. (1979). Development and validation of the eating behavior inventory. Journal of Behavioral Assessment, 1, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01322019 Patel, M. L., Brooks, T. L., & Bennett, G. G. (2020). Consistent self-monitoring in a commercial app-based intervention for weight loss: Results from a randomized trial. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-019-00091-8 Prado, G., Fernandez, A., St George, S. M., Lee, T. K., Lebron, C., Tapia, M. I., Velazquez, M. R., & Messiah, S. E. (2020). Results of a family-based intervention promoting healthy weight strategies in overweight Hispanic adolescents and parents: An RCT. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 59(5), 658–668. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.010 Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12, 38–48. Retrieved from http ://healthpromotionjournal.com. Robbins, L. B., Ling, J., Clevenger, K., Voskuil, V. R., Wasilevich, E., Kerver, J. M., Kaciroti, N., & Pfeiffer, K. A. (2018). A school- and home-based intervention to improve adolescents’ physical activity and healthy eating. The Journal of School Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840518791290, 105984051879129. Romeijn, M. M., Kolen, A. M., Holthuijsen, D. D., Janssen, L., Schep, G., Leclercq, W. K., & van Dielen, F. M. (2020). Effectiveness of a low-calorie diet for liver volume reduction prior to bariatric surgery: A systematic review. Obesity Surgery, 31(1), 350–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-05070-6 Roth, P. L. (1994). Missing data: A conceptual review for applied psychologists. Personnel Psychology, 47, 537–560. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1994.tb01736.x Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 Sharkey, J. R., Nalty, C., Johnson, C. M., & Dean, W. R. (2017). Chapter 10 children’s very low food security is associated with increased dietary intakes in energy, fat, and added sugar among Mexican-origin children (6-11 y) in Texas Border Colonias. Food Insecurity and Disease, 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315365763-11 Silva, M. N., Vieira, P. N., Coutinho, S. R., Minderico, C. S., Matos, M. G., Sardinha, L. B., & Teixeira, P. J. (2010). Using self-determination theory to promote physical activity and weight control: A randomized controlled trial in women. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 33, 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-009-9239-y Skala Dortch, K., Chuang, R.-J., Evans, A., Hedberg, A.-M., Dave, J., & Sharma, S. (2012). Ethnic differences in the home food environment and parental food practices among families of low-income Hispanic and African-American preschoolers. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 14(6), 1014–1022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903012-9575-9 Toh, D. W., Koh, E. S., & Kim, J. E. (2020). Incorporating healthy dietary changes in addition to an increase in fruit and vegetable intake further improves the status of cardiovascular disease risk factors: A systematic review, meta-regression, and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition Reviews, 78(7), 532–545. https:// doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuz104 Trief, P. M., Cibula, D., Delahanty, L. M., & Weinstock, R. S. (2017). Self-determination theory and weight loss in a diabetes prevention program translation trial. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 40(3), 483–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9816-9 United States Department of Agriculture. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans (pp. 2020–2025). Retrieved from https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files /2021-03/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans-2020-2025.pdf. United States Department of Health & Human Services. (2019). Physical activity guidelines for Americans. https://www.hhs.gov/fitness/be-active/physical-activity-guidelines -for-americans/index.html. United States Department of Health & Human Services. (2021). Profile: Hispanic/Latino Americans. Hispanic/latino - the office of minority health. Retrieved October 28, 2021, from https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=64. U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). Hispanic heritage month 2020. The United States census Bureau. Retrieved September 23, 2020, from https://www.census.gov/newsroom /facts-for-features/2020/hispanic-heritage-month.html. UTEP Center for Institutional Evaluation, Research, and Planning. (2020). Factbook. Retrieved October 28, 2021, from https://www.utep.edu/planning/cierp/Files/ docs/past-fact-books1/UTEP%20Fact%20Book%202013-14.pdf. Vallis, M., Ruggiero, L., Greene, G., Jones, H., Zinman, B., Rossi, S., Edwards, L., Rossi, J. S., & Prochaska, J. O. (2003). Stages of change for healthy eating in diabetes: Relation to demographic, eating-related, health care utilization, and psychosocial factors. Diabetes Care, 26, 1468–1474. https://doi.org/10.2337/ diacare.26.5.1468 Wang, D. D., Li, Y., Bhupathiraju, S. N., Rosner, B. A., Sun, Q., Giovannucci, E. L., Rimm, E. B., Manson, J. A. E., Willett, W. C., Stampfer, M. J., & Hu, F. B. (2021). Fruit and vegetable intake and mortality. Circulation, 143(17), 1642–1654. https:// doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.120.048996 Zamarripa, J., Castillo, I., Baños, R., Delgado, M., & Álvarez, O. (2018). Motivational regulations across the stages of change for exercise in the general population of Monterrey (Mexico). Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fpsyg.2018.02368 11