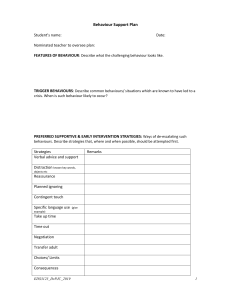

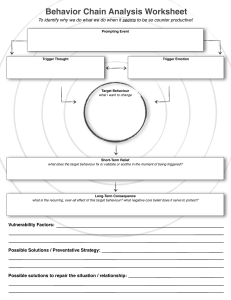

PGSC 7012 formative: Critical Review of Literature related to Teaching and Learning Across and Beyond the School Curriculum Alexander Fisher 2107141 PGCE in Education Secondary Mathematics Institute of Education Word Count (excluding in-text citation and references): 2135 Date of Submission: 27/02/2022 Throughout the nineteen-hundreds there have been a flurry of influential educationalists whose completed works and studies have contributed to radically shifting our perspective and broadening our understanding into what constitutes learning, how learning is achieved, and why it is so very important to us as individuals and as a society. In more recent times, few educational areas of interest have received more attention than classroom management which is demonstrated by extensive research to be essential in realising effective teaching and successful learning outcomes in pupils. In fact, “the most commonly expressed school related concerns of students, teachers, and parents, involves students who are disengaged from planned learning, or who actively disrupt the learning opportunities of others”, which indicates the relevance and necessity of good classroom management by teachers (Cangelosi, 2014, v). The Elton Report refers to unacceptable behaviour as behaviour that causes concern to teachers, which naturally encompasses a range of behaviours that span a continuum from low-level disruptions to more serious behavioural issues (Capel and Leask and Younie, 2019, DES, 1989). Langley (2008) succinctly summarises this continuum of challenging or unacceptable behaviour as behaviour that negatively impacts children’s normal development; is harmful towards themselves or others; or places a child at high risk of social problems or school failure. Traditionally classroom management has had a synonymity with behaviour management typified by explicit forms of discipline teachers exercise in direct response to misbehaviours. Over the last couple of decades, however, there has been a noticeable shift away from reactive approaches to dealing with unwanted behaviour resulting in classroom management taking on broader meaning (Capel and Leask and Younie, 2019). In reality classroom management far extends beyond behaviour management and encompasses a range of strategies and approaches that ultimately support in creating an appropriate classroom climate in which all pupils can effectively learn. To follow I will explore the various perceptions relating to classroom management, as well as demonstrate the clear necessity and importance of good classroom management in the process of learning within the classroom. The national picture of school behaviour is complex. Bennett (2017) highlights, however, multiple indicators suggest that there is room for improvement in a great number of schools and that pupils’ standards of behaviour persists as a significant challenge for many schools. A survey carried out by NASUWT (2013) reveals that “over two thirds of teachers believe there is a widespread problem of poor pupil behaviour in schools and nearly four in ten believe behaviour is a serious problem in their own school”. Bennett (2016) critically identifies that behaviour management impacts all aspects of a pupil’s education and their experience of teaching. Motivation, engagement, well-being, safety, and enjoyment of learning all benefit from improved behaviour and good classroom management. Spielman (2019) expands on this by stating classroom management is a necessary condition for effective learning and the provision of a high-quality education. Student’s behaviour in school strongly correlates with their eventual outcomes, and furthermore, a student’s experience in school remains one of the most insightful indicators for later life success (Bennett, 2017). The Dfe (2019) reveals, according to research undertaken, “More than 82% of parents consider good discipline in the class a key factor when choosing a school for their child.” Bennett (2017, p.6) concludes “With better behaviour management, students achieve more academically, and socially; time is reclaimed for better and more learning; staff satisfaction improves, retention is higher, and recruitment is less problematic”. Therefore, thorough consideration of whole school policy and ethos right down to day-to-day strategies teachers can utilise in their classrooms to ensure good behaviour and classroom management as well as the provision of conducive environments for the best learning outcomes is of paramount importance to school leaders, policy makers, and the school community as a whole. Historically, corporal punishment was commonplace in schools with approaches to discipline being characterised as authoritarian. Since the abolishment of corporal punishment there has been a significant evolution in pervading attitudes towards behaviour management with a trend towards ‘behaviour for learning’ (Capel and Leask and Younie, 2019). Typically, learning and behaviour is unhelpfully viewed as two distinct and different aspects of a teacher’s role (Ellis and Tod, 2015). This view is perpetuated by an over emphasis on behaviour management as a distinct skill set which is often narrowly construed to mean a set of strategies that a teacher utilises to establish and maintain control (Ellis and Tod, 2015). In response, ‘behaviour for learning’ is a conceptual framework which has been developed by reframing behaviour management in terms of promoting learning behaviour, that recognises the various influences on pupil behaviour such as the curriculum, teaching approaches and the teacher–pupil relationship (Capel and Leask and Younie, 2019, Ellis and Tod, 2015). Teachers are encouraged to link pupils’ behaviour with learning via three interconnected relationships: how pupils think about themselves, how they view their relationship with others; and how they perceive themselves as a learner, relative to the curriculum (Capel and Leask and Younie, 2019, Ellis and Tod, 2015). In addition, ‘behaviour for learning’ approaches by recognising the diversity of pupil’s backgrounds and culture, strongly promotes educational inclusion and works to ensure the educational needs of all pupils, irrespective of their level of achievement or the nature of their behaviour, must be met (Capel and Leask and Younie, 2019). The underpinning ideology of educational inclusion can importantly be linked to progressive ideologies purported and developed by Dewey, and contemporaries, including Vygotsky, and Kohn, that promote individuality, appreciate the diversity of pupils needs, and places at the heart of education pupil interest and the development of the whole-being. An important consideration to make before discussing specific classroom management techniques a teacher may utilise is the broader school environment and ecosystem in which classrooms are placed and operate (Marzano, R. and Marzano J. and Pickering, 2003). The task then for policy makers, and school leaders is to promote a positive school culture that is conducive for learning, as well as importantly, maintain it. Garner concludes it remains clear that effective leadership is strongly linked with achieving successful outcomes for students in school, including the promotion of good behaviour and learning (Bennett, 2017). A key aspect for schools and school leaders in promoting a positive climate as well as management of misbehaviour is the ‘whole school behaviour policy’ (Bennett, 2017, Capel and Leask and Younie, 2019). It is essential that the policy, expectations, and ethos that the school creates is understood and promoted by everyone apart of the school community including, teachers, support staff, parents, and the pupils themselves (Bennett, 2017, Capel and Leask and Younie, 2019, Marzano, R. and Marzano J. and Pickering, 2003). Schools’ leaders, most importantly of which the headteacher, must be highly committed and visible as well as supported by a strong leadership team (Bennett, 2017). Communication of the school vision and strategies to achieve this must be clear and well-advertised and there must be an understanding of what the culture looks like in practice from behaviour in classes, corridors, communal areas, as well as around the local community (Bennett, 2017). Importantly in the communication, and maintenance of school wide culture is the deliberate aim to ensure that every aspect of school life feed into and reinforces that culture, and that it is not only reinforced when misdemeanours are observed (Bennett, 2017). A key element to achieving this is to promote and design routines for any repeated activity (Bennett, 2017). How entry and exits procedures from schools’ grounds and classrooms should be carried out, which side of the corridor to walk down and how to queue for lunch, are all opportunities to design routine that can positively feed into to reinforcing the school culture. In promoting and maintaining a positive ethos it is also vital that good behaviour isn’t simply viewed as the absence of ‘bad behaviour’ and that desirable behaviours are consistently promoted and encouraged in pupils as well as acknowledged (Bennett, 2017). This links strongly into ‘behaviour for learning’ ideology and could include helping pupils form good study habits, resilience, strong interpersonal skills, and an ability to cope in adversity or challenging situations. Another key aspect that behaviour policy needs to account for is the diverse range of individuals that can constitute a pupil population (Capel and Leask and Younie, 2019). A school’s approach must attend to the differing needs of pupils that arise from different home environments, language and cultural backgrounds, capabilities, and perspectives (Anthony and Walshaw, 2010). In particular children who are underachieving or have specific learning requirements can display more challenging behaviour. Senior or specialised staff need to proactively support the most vulnerable pupils, and pupils with the greatest behavioural needs, rather than waiting for issues to arise which then require a response (Bennett, 2017). Fundamentally at the core of school wide policy should be high expectations of all students and staff, and a belief that all students matter equally. School-level management and classroom-level management have a symbiotic relationship and unless the frameworks are put in place school wide teachers will find classroom management much more challenging (Marzano, 2006). At the core of a teacher’s responsibility is to ensure the provision of a safe and stimulating learning environment, which is highly dependent on good classroom management (Capel). Within the classroom environment teachers need to consider a range of approaches to promote positive behaviour for learning and to effectively manage the classroom. At the outset teachers should understand that the best way to stop misbehaviour is by trying to prevent it before its starts (Muijs and Reynolds, 2011). Classroom management then inevitably entails a range of preventive strategies that include instilling good routines, applying rules consistently and fairly, ensuring lessons are appropriate and engaging, as well as most importantly developing positive relationships with their pupils. At the outset teachers need to ensure they design and deliver the highest quality lessons. Lessons that are more likely to provoke misbehaviour are generally perceived by pupils to be boring or irrelevant (Muijs and Reynolds, 2011). Furthermore, poor teaching that doesn’t meet or respond to the abilities of pupils precipitates a lot of misbehaviour. Differentiation of tasks to match ability levels as well as appropriate scaffolding are key skills that teachers must master to aid in the realisation of good classroom management (Anthony and Walshaw, 2010, Muijs and Reynolds, 2011). To create an environment that promotes learning teachers must ensure all pupils are motivated by providing well-paced lessons that are stimulating and attend to the interests and needs of all pupils. In addition to the provision of highly stimulating and well-planned lessons teachers must promote clear and consistent routines. Teachers that are either too authoritarian or too lax on discipline invite disruptive behaviour (Muijs and Reynolds, 2011). A commonly known framework for promoting positive classroom behaviour is the 4R’s: rights, responsibilities, rules, and routines. Rules and routines are inextricably linked as routines provided the structures that underpin the rules enabling the smooth running of the classroom (Capel and Leask and Younie, 2019). The more habitual routines become the more likely they will be followed (Muijs and Reynolds, 2011). Applying and promoting adherence to the rules and routines of the classroom and school is extremely important or else they will break down over time (Muijs and Reynolds, 2011). It has been demonstrated that consistency between all staff and students about school values and rules make expectations more simplified and more easily realised (Bennett, 2017). A teacher then should be acutely aware of the school wide ethos and rules, and echo that within their own classrooms. Teachers should also be aware that pupil misbehaviour tends to be observed during the start and end of lessons, during downtime and transitions (Muijs and Reynolds, 2011). Addressing these sections of lessons is key when establishing routines which if done effectively and consistently from the beginning of the year can save teachers a lot of time later in the year (Muijs and Reynolds, 2011). A consideration for school leaders when developing whole school policy is the number and clarity of rules. Too many rules that are over convoluted become difficult to apply fairly, consistently, can be viewed as oppressive by pupils, and inevitably become soon ignored (Bennett, 2017, Muijs and Reynolds, 2011). The teacher-pupil relationship is a crucial factor when instilling rules and routines into pupils as well as more generally classroom management. Rights and responsibilities are key components which are outlined in the 4R’s. A teacher must treat pupils with respect and ensure the pupil feels safe and are able to learn (Capel and Leask and Younie, 2019). By promoting good relationships pupils are more likely to abide by teachers’ expectations, and a positive classroom climate will ensue. Frequent use of praise, both verbal and non-verbal is key in developing relationships (Bennett, 2017). Another aspect that Pollard (2014) notes is the importance of learning pupils’ names, which is of course crucial in establishing the groundwork for positive relationships with individual children. Teacher also need to be aware of pupils specific needs to adapt teaching appropriately which is helped and strengthened by good relationships. Overall good teacher-pupil relationships form the basis for good and effective classroom management, and impact on all aspects of teaching. Parson (2012) identifies behaviour problems increase stress levels for all within the classroom, disturb the flow and delivery of lessons, as well as conflict with the learning process and objectives. A range of strategies to manage behaviour and promote a positive climate in school must be utilised and will include consideration to school wide policy, classroom-based rules, and routines, as well as individual child-focused interventions. Key to realising is good classroom management is a preventative approach in which teachers form good relationships with pupils, design and deliver appropriate and engaging lessons and reinforce the school ethos and culture. Effective teaching and positively functioning classrooms with low levels of disruptive behaviour ultimately require a lot planning and consistency and is fundamental to the provision of a high-quality education for all (Bennett, 2017). References Anthony, G. and Walshaw, M., 2010. Effective pedagogy in mathematics. Brussels: Internat. Acad. of Education, pp. 6, 8-9, 15-17 Bennett, T., 2016. [online] Assets.publishing.service.gov.uk. Available at: <https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_d ata/file/536889/Behaviour_Management_report_final__11_July_2016.pdf> [Accessed 3 February 2022]. Bennett, T., 2017. Creating a Culture: How School Leaders Can Optimise Behaviour. Independent Review of Behaviour in Schools. [online] London: Crown. Available at: <https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/602487/To m_Bennett_Independent_Review_of_Behaviour_in_Schools.pdf> [Accessed 02 February 2022]. Cangelosi, J., 2014. Classroom management strategies. 7th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., v. Capel, S.A., Leask, M. and Younie, S., 2019. Learning to teach in the secondary school: a companion to school experience. 8th ed. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, Ny: Routledge, p.168. Department for Education and Science, 1989. Discipline in schools (The Elton Report). London: HMSO, p. 102 Department for Education. 2019. Schools backed to tackle bad behaviour. [online] Available at: <https://www.gov.uk/government/news/schools-backed-to-tackle-bad-behaviour> [Accessed 2 February 2022]. Ellis, S. and Tod, J., 2015. Promoting behaviour for learning in the classroom. Routledge. Langley, D., 2008. Student Challenging behaviour and its impact on classroom culture. The University of Waikato, Hamilton NASUWT, 2013. WIDESPREAD CONCERN OVER PUPIL BEHAVIOUR. [online] North Yorkshire Federation. Available at: <https://nasuwtny.wordpress.com/2013/04/02/widespread-concernover-pupil-behaviour/> [Accessed 6 February 2022]. Parsonson, B.S. 2012. Evidence-Based Classroom Behaviour Management Strategies. Ministry of Education: Special Education, Hawkes Bay Region. Pollard, A., 2014. Reflective teaching in schools. London: Bloomsbury. Marzano, R., 2006. A handbook for classroom management that works. Heatherton, Vic.: Hawker Brownlee Education. Marzano, R., Marzano, J. and Pickering, D., 2003. Classroom management that works. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development Muijs, D. and Reynolds, D., 2011. Effective teaching: evidence and practice. Los Angeles, Calif.; London: Sage, p.88. Spielman, A., 2019. HMCI commentary: managing behaviour research. [online] GOV.UK. Available at: <https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/research-commentary-managing-behaviour> [Accessed 4 February 2022].