Managing the Profitable Construction Business, 1e Thomas Schleifer, Kenneth Sullivan, John Murdough

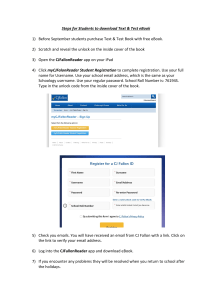

advertisement