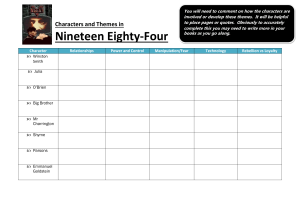

8/6/23, 1:30 PM William Sterling Parsons - Wikipedia William Sterling Parsons William Sterling "Deak" Parsons (26 November 1901 – 5 December 1953) was an American naval officer who worked as an ordnance expert on the Manhattan Project during World War II. He is best known for being the weaponeer on the Enola Gay, the aircraft which dropped a Little Boy atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945. To avoid the possibility of a nuclear explosion if the aircraft crashed and burned on takeoff, he decided to arm the bomb in flight. While the aircraft was en route to Hiroshima, Parsons climbed into the cramped and dark bomb bay, and inserted the powder charge and detonator. He was awarded the Silver Star for his part in the mission. A 1922 graduate of the United States Naval Academy, Parsons served on a variety of warships beginning with the battleship USS Idaho. He was trained in ordnance and studied ballistics under L. T. E. Thompson at the Naval Proving Ground in Dahlgren, Virginia. In July 1933, Parsons became liaison officer between the Bureau of Ordnance and the Naval Research Laboratory. He became interested in radar and was one of the first to recognize its potential to locate ships and aircraft, and perhaps even track shells in flight. In September 1940, Parsons and Merle Tuve of the National Defense Research Committee began work on the development of the proximity fuze, an invention that was provided to the US by the UK Tizard Mission, a radar-triggered fuze that would explode a shell in the proximity of the target. The fuze, eventually known as the VT (variable time) fuze, Mark 32, went into production in 1942. Parsons was on hand to watch the cruiser USS Helena shoot down the first enemy aircraft with a VT fuze in the Solomon Islands in January 1943. In June 1943, Parsons joined the Manhattan Project as Associate Director at the Project Y research laboratory at Los Alamos, New Mexico, under J. Robert Oppenheimer. Parsons became responsible for the ordnance aspects of the project, including the design and testing of the non-nuclear components of nuclear weapons. In a reorganization in 1944, he lost responsibility for the implosion-type fission weapon, but retained that for the design and development of the gun-type fission weapon, which eventually became Little Boy. He was also responsible for the delivery program, codenamed Project Alberta. He watched the Trinity nuclear test from a B-29. Rear Admiral William Sterling "Deak" Parsons Rear Admiral William S. Parsons Nickname(s) "Deak" Born 26 November 1901 Chicago, Illinois, US Died 5 December 1953 (aged 52) Bethesda, Maryland, US Place of burial Arlington National Cemetery Allegiance Service/ branch United States Navy Years of service 1922–1953 Rank Battles/wars https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Sterling_Parsons United States Rear admiral World War II: 1/14 8/6/23, 1:30 PM William Sterling Parsons - Wikipedia After the war, Parsons was promoted to the rank of rear admiral without ever having commanded a ship. He participated in Operation Crossroads, the nuclear weapon tests at Bikini Atoll in 1946, and later the Operation Sandstone tests at Enewetak Atoll in 1948. In 1947, he became deputy commander of the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project. He died of a heart attack on 5 December 1953. Early life Guadalcanal Campaign Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Korean War Awards Navy Distinguished Service Medal Silver Star Legion of Merit William Sterling Parsons was born in Chicago, Illinois, on 26 November 1901, the oldest of three children of a lawyer, Harry Robert Parsons, and his wife Clara, née Doolittle. Clara was the granddaughter of James Rood Doolittle, who served as US Senator from Wisconsin between 1857 and 1869, and of Joel Aldrich Matteson, Governor of Illinois from 1853 to 1857. In 1909, the family moved to Fort Sumner, New Mexico,[1] where William learned to speak fluent Spanish.[2] He attended the local schools in Fort Sumner and was home schooled by his mother for a time. He commenced at Santa Rosa High School, where his mother taught English and Spanish, rapidly advancing through three years in just one. In 1917 he attended Fort Sumner High School, from which he graduated in 1918.[3] In 1917 Parsons traveled to Roswell, New Mexico, to take the United States Naval Academy exam for one of the appointments by Senator Andrieus A. Jones. He was only an alternate, but passed the exam while more favored candidates did not, and received the appointment. As he was only 16, two years younger than most candidates, he was shorter and lighter than the physical standards called for, but managed to convince the examining board to admit him anyway. He entered the Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, in 1918, and eventually graduated 48th out of 539 in the class of 1922, in which Hyman G. Rickover graduated 107th. At the time, it was customary for midshipmen to acquire nicknames, and Parsons was called "Deacon", a play on his last name. This became shortened to "Deak".[4] Ordnance On graduating in June 1922, Parsons was commissioned as an ensign and posted to the battleship USS Idaho,[5] where he was placed in charge of one of the 14-inch gun turrets.[6] In May 1927, Parsons, now a lieutenant (junior grade), returned to Annapolis, where he commenced a course in ordnance at the Naval Postgraduate School.[7] He became friends with Lieutenant Jack Crenshaw, a fellow officer attending the same training course. Jack asked Parsons to be best man at his wedding to Betty Cluverius, the daughter of the Commandant of the Norfolk Navy Yard, Rear Admiral Wat Tyler Cluverius Jr., at the Norfolk Navy Chapel. As best man, Parsons was paired with Betty's maid of honor, her sister Martha. Parsons and Martha got along well, and in November 1929, they too were married at the Norfolk Navy Chapel. This time, Jack and Betty were best man and maid of honor.[8] The ordnance course was normally followed by a relevant field posting, so Parsons was sent to the Naval Proving Ground in Dahlgren, Virginia, to further study ballistics under L. T. E. Thompson.[9] Following the usual pattern of alternating duty afloat and ashore, Parsons was posted to the battleship USS Texas in June 1930, with the rank of lieutenant. In November, the Commander in Chief United https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Sterling_Parsons 2/14 8/6/23, 1:30 PM William Sterling Parsons - Wikipedia States Fleet, Admiral Jehu V. Chase, hoisted his flag on the Texas, bringing Cluverius with him as his chief of staff. This was awkward for Parsons, his son-in-law, but Cluverius understood, being himself the son-in-law of an admiral,[10] in his case, Admiral William T. Sampson.[11] In July 1933, Parsons became liaison officer between the Bureau of Ordnance and the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) in Washington, DC.[5] At the NRL he was briefed by the head of its Radio Division, A. Hoyt Taylor, who told him about experiments Naval Research Laboratory that had been carried out into what the Navy would later name complex on the Potomac River in radar.[12][13] Parsons immediately recognized the potential of the Washington, DC new invention to locate ships and aircraft, and perhaps even track shells in flight. For this, he realized that he was going to need high frequency microwaves. He discovered that no one had attempted this. The scientists had not considered all the applications of the technology, and the Navy bureaus had not grasped their potential. He was able to persuade the scientists to establish a group to investigate microwave radar, but without official sanction it had low priority. Parsons submitted a memorandum on the subject to the Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) requesting $5,000 per annum for research. To his dismay, the BuOrd and Bureau of Engineering, which was responsible for the NRL, turned down his proposal.[14] Some thought that Parsons was ruining his career with his advocacy of radar,[15] but he acquired one powerful backer. The Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer), Rear Admiral Ernest J. King, supported the use of radar as a means of determining aircraft altitude. When the Bureau of Engineering protested that such a device would necessarily be too large to carry on a plane, King told them that it would still be worthwhile, even if the only aircraft in the Navy big enough to carry it was the airship USS Macon.[16] Parsons' marriage produced three daughters. The first, Hannah, was born in 1932; the second, Margaret (Peggy), followed in 1934. Hannah died of polio in April 1935.[17][18] Parsons returned to sea in June 1936 as the executive officer of the destroyer USS Aylwin. He was promoted to lieutenant commander in May 1937. His third daughter, Clara (Clare), was born the same year. On that occasion, Parsons left Martha with the newborn and three-year-old Peggy to care for and reported for duty the next day, believing that his first responsibility was to his ship. His skipper, Commander Earl E. Stone, did not agree, and sent him home. In March 1938, Rear Admiral William R. Sexton had Parsons assigned to his flagship, the cruiser USS Detroit, as gunnery officer. Parsons' task was to improve the gunnery scores of his command, and in this he succeeded.[19] Proximity fuze Parsons was posted back to Dahlgren in September 1939 as experimental officer. The atmosphere had changed considerably. In June 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved the creation of the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC), under the direction of Vannevar Bush. Richard C. Tolman, dean of the graduate school at Caltech, was given responsibility for the NDRC's Armor and Ordnance Division. Tolman met with Parsons and Thompson in July 1940, and discussed their needs. Within the Navy, too, there was a change of attitude, with Captain William H. P. (Spike) Blandy as the head of BuOrd's Research Desk. Blandy welcomed the assistance of NDRC scientists in improving and developing weapons.[20] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Sterling_Parsons 3/14 8/6/23, 1:30 PM William Sterling Parsons - Wikipedia In September 1940, Parsons and Merle Tuve of NDRC began work on a new concept. Shooting down an aircraft with an anti-aircraft gun was a difficult proposition. As a shell had to hit a speeding aircraft at an uncertain altitude, the only hope seemed to be to fill the sky with ammunition. A direct hit was not actually required; an aircraft might be destroyed or critically damaged by a shell detonating nearby. With this in mind, anti-aircraft gunners used time fuzes to increase the possibility of damage. The question then arose as to whether radar could be used to create an explosion in the proximity of an aircraft. Tuve's first suggestion was to have an aircraft drop a radar-controlled bomb on a bomber formation. Parsons saw that while this was technically feasible, it was tactically problematic.[21] The ideal solution was a proximity fuze inside an artillery shell as was first conceived by W. A. S. Butement, Edward S. Shire, and Amherst F. H. Thomson, researchers at the British Cut away diagram of the proximity Telecommunications Research Establishment[22] but there were fuze Mark 53 numerous technical difficulties with this. The radar set had to be made small enough to fit inside a shell, and its glass vacuum tubes had to first withstand the 20,000 g force of being fired from a gun, and then 500 rotations per second in flight. A special Section T of NDRC was created, chaired by Tuve, with Parsons as special assistant to Bush and liaison between NDRC and BuOrd.[23] On 29 January 1942, Parsons reported to Blandy that a batch of fifty proximity fuzes from the pilot production plant had been test fired, and 26 of them had exploded correctly. Blandy therefore ordered full-scale production to begin. In April 1942, Bush, now the Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), placed the project directly under OSRD. The research effort remained under Tuve but moved to the Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), where Parsons was BuOrd's representative.[24] In August 1942, a live firing test was conducted with the newly commissioned cruiser USS Cleveland. Three pilotless drones were shot down in succession.[25] Parsons had the new proximity fuzes, now known as VT (variable time) fuze, Mark 32, flown to the Mare Island Navy Yard, where they were mated with 5"/38 caliber gun rounds. Some 5,000 of them were then shipped to the South Pacific. Parsons flew there himself, where he met with Admiral William F. Halsey at his headquarters in Nouméa. He arranged for Parsons to take VT fuzes out with him on the cruiser USS Helena.[26][27] On 6 January 1943, Helena was part of a cruiser force that bombarded Munda in the Solomon Islands. On the return trip, the cruisers were attacked by four Aichi D3A (Val) dive bombers. Helena fired at one with a VT fuze. It exploded close to the aircraft, which crashed into the sea.[28] To preserve the secrecy of the weapon, its use was initially permitted only over water, where a dud round could not fall into enemy hands. In late 1943, the Army obtained permission for it to be used over land. It proved particularly effective against the V-1 flying bomb over England, and later Antwerp https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Sterling_Parsons 4/14 8/6/23, 1:30 PM William Sterling Parsons - Wikipedia in 1944. The use of a version fired from howitzers against ground targets was authorized in response to the German Ardennes Offensive in December 1944, with deadly effect. By the end of 1944, VT fuzes were coming off the production lines at the rate of 40,000 per day.[29] Manhattan Project Project Y Parsons returned to Dahlgren in March 1943.[30] Around this time, a research laboratory was established at Los Alamos, New Mexico, under the direction of J. Robert Oppenheimer as Project Y, which was part of the Manhattan Project, the top-secret effort to develop an atomic bomb. The creation of a practical weapon would necessarily require an expert in ordnance, and Oppenheimer tentatively penciled in Tolman for the role, but getting him released from OSRD was another matter.[31] Until then, Oppenheimer had to do the job himself.[32] In May 1943, the Captain Parsons on Tinian in 1945 Manhattan Project's director, Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves, took up the matter with the Military Policy Committee, the highlevel committee that oversaw the Manhattan Project. It consisted of Vannevar Bush as its chairman, Brigadier General Wilhelm D. Styer who represented the Army, and Rear Admiral William R. Purnell as the Navy's representative.[33] Groves told them that he was looking for someone with "a sound understanding of both practical and theoretical ordnance – high explosives, guns and fusing – a wide acquaintance and an excellent reputation among military ordnance people and an ability to gain their support; a reasonably broad background in scientific development; and an ability to attract and hold the respect of scientists."[34] He said that a military officer would be his ideal, as the job might involve planning and coordinating the use of the bomb, but added that he knew of no Army officer who fit the bill. Bush then suggested Parsons, a nomination supported by Purnell.[35] The next morning, Parsons received a phone call from Purnell, ordering him to report to Admiral King, who was now the Commander in Chief, US Fleet (Cominch). In a terse ten-minute meeting, King briefed Parsons on the Project, which he said had his full backing.[36] That afternoon, Parsons met with Groves, who quickly sized him up as the right man for the job.[35] "Thin Man" plutonium gun test casings at Wendover Army Air Field. In the background, casing designs for "Fat Man" bombs can be seen as well. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Sterling_Parsons Parsons was relieved of his duties at Dahlgren and officially assigned to Admiral King's Cominch staff on 1 June 1943, with a promotion to the rank of captain. On 15 June 1943 he arrived at Los Alamos as Associate Director.[37] Parsons would be Oppenheimer's second in command.[38] Parsons and his family moved into one of the houses on "Bathtub Row" that had formerly belonged to the headmaster and staff of the Los Alamos Ranch School. Bathtub Row, so-called because the houses were the only ones at Los Alamos with bathtubs, was the most prestigious address at Los Alamos.[39] Parsons became Oppenheimer's nextdoor neighbor,[40] and in fact his house was slightly larger, because Parsons had two children and Oppenheimer, at this point, had only one.[41] With two school-age children, Parsons took a 5/14 8/6/23, 1:30 PM William Sterling Parsons - Wikipedia keen interest in the construction of the Central School at Los Alamos, and became president of the school board. Instead of the temporary two-story structure that Groves had envisioned in the interest of economy and not misusing the project's high priorities for labor and materials, Parsons had a wellbuilt, modern, single-story school constructed. On seeing the result, Groves said: "I'll hold you personally responsible for this, Parsons."[42] Oppenheimer had already recruited key people for Parsons' Ordnance Division. Edwin McMillan was a physicist who headed the Proving Ground Group. His first task was to establish the ordnance test area. Later he became Parsons' deputy for the gun-type fission weapon. Charles Critchfield, a mathematical physicist with ordnance experience at the Army's Aberdeen Proving Ground, was in charge of the Target, Projectile and Source Group. Kenneth Bainbridge arrived in August to take charge of the Instrumentation Group. Parsons recruited Robert Brode from the proximity fuze project to become head of the Fuze Development Group. Joseph Hirschfelder was brought in as an expert on internal ballistics, and headed the Interior Ballistics Group. From the beginning, Parsons wanted Norman Ramsey as the head of the delivery group. Edward L. Bowles, the scientific adviser to the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, was reluctant to part with Ramsey, but gave way under pressure from Groves, Tolman and Bush. Perhaps the most controversial group head would be Seth Neddermeyer, the head of the Implosion Experimentation Group; for the time being, Parsons accorded a relatively low priority to this work. He also recruited Hazel Greenbacker as his secretary.[43][44] Groves, among others, felt that Parsons had a tendency to fill positions with Naval officers. There was some aspect of service parochialism, and Parsons believed that involvement in the Manhattan Project would be important for the future of the Navy, but it was also due to the difficulty of getting highly skilled people from any source in wartime. Parsons simply found it easiest to get them through Navy channels.[45] Lieutenant Commander Norris Bradbury said that he did not wish to join Project Y, but was soon on his way to Los Alamos anyway.[46] Parsons recruited Commander Francis Birch, who replaced McMillan at Anchor Ranch.[47] Commander Frederick Ashworth was a Naval ordnance officer and aviator who was senior aviator at Dahlgren when he was brought in to work on the delivery side.[48] By the end of the war, there were 41 Naval officers at Los Alamos.[49] Parsons (right) supervises loading of Little Boy into the bomb bay of Enola Gay. Over the next few months, Parsons' division designed the gun-type plutonium weapon, codenamed Thin Man. It was assumed that a uranium-235 weapon would be similar in nature. Hirschfelder's group considered various designs, and evaluated different propellants.[50] The ordnance test area, which became known as "Anchor Ranch", was established on a nearby ranch, where Parsons conducted test firings with a 3-inch anti-aircraft gun.[51] Work on implosion lagged by comparison, but this was not initially a major concern, because it was expected that the gun-type would work with both uranium and plutonium. However, Oppenheimer, Groves and Parsons lobbied Purnell and Tolman to get John von Neumann to have a look at the problem. Von Neumann suggested the use of shaped charges to initiate implosion.[52] Oppenheimer considered that there was a "reciprocal lack of confidence" between Parsons and Neddermeyer,[53] and in October 1943 he brought in George Kistiakowsky, who began a new attack on the implosion design.[53] Kistiakowsky clashed with both Parsons and Neddermeyer, but felt that "my disagreements with Deak Parsons were very minor compared to my disagreements with https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Sterling_Parsons 6/14 8/6/23, 1:30 PM A gun-type nuclear bomb William Sterling Parsons - Wikipedia Neddermeyer."[54] The implosion design acquired a new urgency in April 1944, when studies of reactor-produced plutonium confirmed that it could not be used in a gun-type weapon. An accelerated effort was called for to design and build the implosiontype weapon, codenamed Fat Man. Two new groups were created at Los Alamos: X (for explosives) Division headed by Kistiakowsky, and G (for gadget) Division under Robert Bacher. Parsons was placed in charge of O (for ordnance) Division, with responsibility for both the gun-type design and delivery.[55] The uranium gun-type weapon known as Little Boy did prove to be simpler than Thin Man. The gun velocity needed to be only 1,000 feet per second (300 m/s), a third that of Thin Man. A corresponding reduction in the barrel length reduced the bomb's overall length to 6 feet (1.8 m). In turn, this made it much easier to handle, and permitted a conventional bomb shape, resulting in a more predictable flight.[56] The main concerns with Little Boy were its safety and reliability.[57] Project Alberta The delivery program, codenamed Project Alberta, got underway under Ramsey's direction in October 1943. Starting in November, the Army Air Forces Materiel Command at Wright Field, Ohio, began Silverplate, the codename for the modification of B-29s to Enola Gay after Hiroshima mission, carry the bombs. Parsons arranged for a test program at Dahlgren entering hardstand using scale models of Thin Man and Fat Man. Test drops were carried out at Muroc Army Air Field, California, and the Naval Ordnance Test Station at Inyokern, California, using full-size replicas of Fat Man known as pumpkin bombs. The ungainly and non-aerodynamic shape of Fat Man proved to be the main difficulty, but many other problems were encountered and overcome.[58][59] Parsons, wrote Oppenheimer, "has been almost alone in this project to appreciate the actual military and engineering problems which we would encounter. He has been almost alone in insisting on facing these problems at a date early enough so that we might arrive at their solution."[56] The "Tinian Joint Chiefs": Captain William S. Parsons (left), Rear Admiral William R. Purnell (center), and Brigadier General Thomas F. Farrell (right) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Sterling_Parsons In July 1944, Parsons joined Jack Crenshaw, who was investigating the Port Chicago disaster. The two men surveyed the disaster area, where 1,500 tons of munitions had exploded and 320 men had died.[60] A year later, Parsons watched the Trinity nuclear test from a circling B-29.[61] Afterwards, Parsons flew to Tinian, where the B-29s of Colonel Paul W. Tibbets' 509th Composite Group were preparing to deliver the weapons. En route, he stopped off in San Diego to visit his eighteen-year-old half-brother Bob, a U.S. Marine who had been badly wounded in the Battle of Iwo Jima.[62] Parsons also met with Captain Charles B. McVay III, the skipper of the cruiser USS Indianapolis, in Purnell's office at the Embarcadero in San Francisco and gave McVay his orders: 7/14 8/6/23, 1:30 PM William Sterling Parsons - Wikipedia You will sail at high speed to Tinian where your cargo will be not be told what the cargo is, but it is to be guarded even afte goes down, save the cargo at all costs, in a lifeboat if necessar your voyage will cut the length of the war by just that much.[6 Parsons was in charge of scientists and technicians from Project Alberta on Tinian, who were nominally organized as the 1st Technical Service Detachment. Their role was the handling and maintenance of the nuclear weapons. Parsons was joined by Purnell, who represented the Military Liaison Committee, and Brigadier General Thomas F. Farrell, Groves' Deputy for Operations. They became, informally, the "Tinian Joint Chiefs", with decision-making authority over the nuclear mission. Before Farrell left for Tinian, Groves had told him: "Don't let Parsons get killed. We need him!"[64] In the space of a week on Tinian, four B-29s crashed and burned on the runway. Parsons became very concerned. If a B-29 crashed with a Little Boy, the fire could cook off the explosive and detonate the weapon, with catastrophic consequences. He raised the possibility of arming the bomb in flight with Farrell, who agreed that it might be a good idea. Farrell asked Parsons if he knew how to perform this task. "No sir, I don't", Parsons conceded, "but I've got all afternoon to learn."[65] The night before the mission, Parsons repeatedly practiced inserting the powder charge and detonator in the bomb in the poor visibility and cramped conditions of the bomb bay.[66] Presentation of the Army–Navy "E" Award at Los Alamos on 16 October 1945. Standing, left to right: J. Robert Oppenheimer, unidentified, unidentified, Kenneth Nichols, Leslie Groves, Robert Gordon Sproul, Deak Parsons. Parsons participated in the bombing of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, flying on the Enola Gay as weaponeer and Senior Military Technical Observer.[67] Shortly after takeoff, he clambered into the bomb bay and carefully carried out the procedure that he had rehearsed the night before. It was Parsons and not Tibbets, the pilot, who was in charge of the mission. He approved the choice of Hiroshima as the target, and gave the final approval for the bomb to be released. For his part in the mission, Parsons was awarded the Silver Star,[68] and was promoted to the wartime rank of commodore on 10 August 1945.[5] For his work on the Manhattan Project, he was awarded the Navy Distinguished Service Medal.[69] Postwar career In November 1945, King created a new position of Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Special Weapons, which was given to Vice Admiral Blandy. Parsons became Blandy's assistant. In turn, Parsons had two assistants of his own, Ashworth and Horacio Rivero Jr. He also brought Greenbacker from Los Alamos to help set up the new office.[70] Parsons was a strong supporter of research into the use of nuclear power for warship propulsion, but disagreed with Rear Admiral Harold G. Bowen Sr., the head of the Office of Research and Inventions, who wanted the U.S. Navy to initiate its own nuclear project. Parsons felt that the Navy should work with the Manhattan Project, and arranged for Navy officers to be assigned to Oak Ridge. The most senior of them was his former classmate Rickover, who became assistant director there. They immersed themselves in the study of nuclear energy, laying the foundations for a nuclear-powered navy.[71] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Sterling_Parsons 8/14 8/6/23, 1:30 PM William Sterling Parsons - Wikipedia On 11 January 1946, Blandy was appointed to command Joint Task Force One (JTF-1), a special force created to conduct a series of nuclear weapon tests at Bikini Atoll, which he named Operation Crossroads, to determine the effect of nuclear weapons on warships.[72] Parsons, who was promoted to the rank of rear admiral on 8 January 1946, became Blandy's Deputy Commander for Technical Direction and Commander Task Group 1.1.[5] Parsons worked hard to make a success of the operation, which he described as "the largest laboratory experiment in history".[73] In addition to the 95 target ships, there was a support fleet of more than 150 ships, 156 aircraft, and over 42,000 personnel.[74] Parsons witnessed the first explosion, Able, from the deck of the task force flagship, the command ship USS Mount McKinley. An airburst like News conference on board the Hiroshima blast, it was unimpressive, and even Parsons thought that the amphibious command it must have been smaller than the Hiroshima bomb. It failed to sink the ship USS Appalachian target ship, the battleship USS Nevada, mainly because it missed it by a during Operation considerable distance. This made it difficult to assess the amount of Crossroads. In foreground damage caused, which was the objective of the exercise. Blandy then is Parsons, Major General William E. Kepner and Vice announced that the next test, Baker, would occur in just three weeks. This Admiral William H. P. meant that Parsons had to carry out the evaluation of Able Blandy. Colonel Stafford L. simultaneously with the preparations for Baker. This time he assisted Warren holds the with the final preparations on USS LSM-60 before heading back to microphone. seaplane tender USS Cumberland Sound for the test. The underwater Baker explosion was no larger than Able, but the dome and water column made it look far more spectacular. The real problem was the radioactive fallout, as Colonel Stafford L. Warren, the Manhattan Project's medical advisor, had predicted. The target ships proved impossible to decontaminate and, lacking targets, the test series had to be called off.[75] For his part in Operation Crossroads, Parsons was awarded the Legion of Merit.[76] The Special Weapons Office was abolished in November 1946, and the Manhattan Project followed suit at the end of the year. A civilian agency, the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), was created by the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 to take over the functions and assets of the Manhattan Project, including development, production and control of nuclear weapons. The law provided for a Military Liaison Committee (MLC) to advise the AEC on military matters, and Parsons became a member. A joint Army-Navy organization, the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project (AFSWP), was created to handle the military aspects of nuclear weapons.[77] Groves was appointed to command the AFSWP, with Parsons and Air Force Major General Roscoe C. Wilson as his deputies. In this capacity, Parsons pressed for the development of improved nuclear weapons. During the Operation Sandstone series of nuclear weapon tests at Enewetak Atoll in 1948, Parsons once again served as deputy commander.[78] Parsons hoped that his next posting would be to sea, but he was instead sent to the Weapons Systems Evaluation Group in 1949. He finally returned to sea duty in 1951, this time as Commander, Cruiser Division 6, despite having never commanded a ship. Parsons and his cruisers conducted a tour of the Mediterranean showing the flag. He then became Deputy Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance in March 1952.[79] Death and legacy Parsons remained in contact with Oppenheimer. The two men and their wives visited each other from time to time, and the Parsons family especially enjoyed visiting its former neighbors at their new home at Olden Manor,[80] a 17th-century estate with a cook and groundskeeper, surrounded by 265 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Sterling_Parsons 9/14 8/6/23, 1:30 PM William Sterling Parsons - Wikipedia acres (107 ha) of woodlands at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey.[81] Parsons was disturbed by the rise of McCarthyism in the early 1950s. In 1953 he wrote a letter to Oppenheimer expressing his hope that "the anti-intellectualism of recent months may have passed its peak". On 4 December that year, Parsons heard of President Dwight Eisenhower's "blank wall" directive, blocking Oppenheimer from access to classified material. Parsons became visibly upset, and that night began experiencing severe chest pains.[82] The next morning, he went to Bethesda Naval Hospital, where he died while the doctors were still examining him.[83] He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery alongside his daughter Hannah.[17] He was survived by his father, brother, half-brother and sister, as well as his wife Martha and daughters Peggy and Clare.[84] The Rear Admiral William S. Parsons Award for Scientific and Technical Progress was established by the Navy in his memory. It is awarded "to a Navy or Marine Corps officer, enlisted person, or civilian who has made an outstanding contribution in any field of science that has furthered the development and progress of the Navy or Marine Corps."[85] The Forrest Sherman-class destroyer USS Parsons was named in his honor. Her keel was laid down by Ingalls Shipbuilding of Pascagoula, Mississippi, on 17 June 1957 and was launched by his widow Martha on 17 August 1958.[5] When it was rechristened as a guided missile destroyer (DDG-33) in 1967, Clare, now a Naval officer herself, represented her family.[86] Parsons was decommissioned on 19 November 1982, stricken from the Navy list on 1 December 1984, and disposed of as a target on 25 April 1989.[87] The Deak Parsons Center, headquarters of Afloat Training Group, Atlantic, in Norfolk, Virginia, was also named for him.[84] Parsons' portrait is among a series of paintings related to Operation Crossroads.[88] His papers are in the Naval Historical Center in Washington, DC.[89] In popular culture Parsons was depicted in the following films: The Beginning or the End (1947) by Warner Anderson Above and Beyond by Larry Gates Enola Gay: The Men, the Mission, the Atomic Bomb (1980) by Robert Pine Day One by Dee McCafferty Fat Man and Little Boy (1989) by Michael Brockman Hiroshima (1995) by Gary Reineke Notes 1. Christman 1998, pp. 6–9. 2. Christman 1998, p. 17. 3. Christman 1998, pp. 12–13. 4. Christman 1998, pp. 13–18. 5. "Parsons" (https://web.archive.org/web/20121022182909/http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/p2/par sons.htm). US Naval Historical Center. Archived from the original (http://www.history.navy.mil/danf s/p2/parsons.htm) on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2011. 6. Christman 1998, p. 25. 7. Christman 1998, pp. 29–30. 8. Christman 1998, pp. 32–34. 9. Christman 1998, pp. 38–39. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Sterling_Parsons 10/14 8/6/23, 1:30 PM William Sterling Parsons - Wikipedia 10. Christman 1998, pp. 38–40. 11. Ault, Jon. "William Sampson" (http://www.spanamwar.com/sampson.htm). Spanish American War Centennial Website. Retrieved 24 July 2011. 12. Christman 1998, p. 45. 13. Terrett 1953, pp. 39–41. 14. Christman 1998, pp. 45–49. 15. Christman 1998, p. 49. 16. Christman 1998, p. 53. 17. "William Sterling Parsons Rear Admiral, United States Navy" (http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/wp arsons.htm). Arlington National Cemetery. Retrieved 24 July 2011. 18. Christman 1998, pp. 43, 54–55. 19. Christman 1998, pp. 57–61. 20. Christman 1998, pp. 72–73. 21. Christman 1998, pp. 74–77. 22. Brennan, James W. (December 1968). "The Proximity Fuze Whose Brainchild?" (https://www.usni. org/magazines/proceedings/1968/september/proximity-fuze-whose-brainchild). United States Naval Institute Proceedings: 72–78. Retrieved 6 April 2019. 23. Furer 1959, pp. 346–347. 24. Christman 1998, pp. 86–91. 25. Furer 1959, p. 348. 26. "Radio Proximty (VT) Fuzes" (https://web.archive.org/web/20140209105150/http://www.history.na vy.mil/faqs/faq96-1.htm). Naval Historical Center. Archived from the original (http://www.history.na vy.mil/faqs/faq96-1.htm) on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2011. 27. Christman 1998, pp. 96–98. 28. Morison 1948, pp. 329–330. 29. Furer 1959, p. 349. 30. Christman 1998, p. 102. 31. Christman 1998, pp. 106–107. 32. Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 83–84. 33. Groves 1962, pp. 24–25. 34. Groves 1962, pp. 159–160. 35. Groves 1962, p. 160. 36. Christman 1998, p. 108. 37. Christman 1998, pp. 112–115. 38. Christman 1998, p. 148. 39. Hunner 2004, p. 32. 40. Hunner 2004, p. 193. 41. Christman 1998, p. 118. 42. Hunner 2004, pp. 50–51. 43. Christman 1998, pp. 120–127, 131. 44. Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 84–85. 45. Christman 1998, pp. 153–154. 46. Christman 1998, p. 139. 47. Christman 1998, p. 144. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Sterling_Parsons 11/14 8/6/23, 1:30 PM William Sterling Parsons - Wikipedia 48. Christman 1998, p. 152. 49. Christman 1998, p. 133. 50. Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 112–114. 51. Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 116–118. 52. Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 130–132. 53. Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 137 54. Christman 1998, p. 138. 55. Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 242–246. 56. Christman 1998, p. 149. 57. Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 261–263. 58. Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 378–381. 59. Christman 1998, p. 167. 60. Christman 1998, pp. 154–155. 61. Christman 1998, pp. 170–171. 62. Christman 1998, pp. 173–174. 63. Thomas & Morgan-Witts 1977, p. 279. 64. Christman 1998, p. 176. 65. Lewis & Tolzer 1957, p. 72. 66. Thomas & Morgan-Witts 1977, p. 383. 67. Thomas & Morgan-Witts 1977, pp. 372–373. 68. "Citations for Awards of the Silver Star to U.S. Navy Personnel in World War II" (https://web.archiv e.org/web/20100727041518/http://www.homeofheroes.com/members/04_SS/2_WWII/citations/na vy/a.html). Military Times. Archived from the original (http://www.homeofheroes.com/members/04_ SS/2_WWII/citations/navy/a.html) on 27 July 2010. Retrieved 26 July 2011. 69. Christman 1998, p. 204. 70. Christman 1998, pp. 210–211. 71. Hewlett & Duncan 1969, pp. 74–76. 72. Weisgall 1994, p. 31. 73. Christman 1998, pp. 220–221. 74. Shurcliff 1947, p. 2. 75. Christman 1998, pp. 224–231. 76. Christman 1998, p. 257. 77. Groves 1962, pp. 394–399. 78. Christman 1998, pp. 234–239. 79. Christman 1998, pp. 240–246. 80. Christman 1998, p. 242. 81. Bird & Sherwin 2005, p. 369. 82. Bird & Sherwin 2005, pp. 480–481. 83. Christman 1998, pp. 249–250. 84. Christman 1998, p. 258. 85. "Sea Service Awards Descriptions" (https://web.archive.org/web/20110927162745/http://www.nav yleague.org/councils/awards_manual.pdf) (PDF). Navy League of the United States. Archived from the original (http://www.navyleague.org/councils/awards_manual.pdf) (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Sterling_Parsons 12/14 8/6/23, 1:30 PM William Sterling Parsons - Wikipedia 86. Christman 1998, p. 253. 87. Willshaw, Fred. "USS Parsons (DD-949 / DDG-33)" (http://www.navsource.org/archives/05/949.ht m). NavSource Naval History. Retrieved 30 July 2011. 88. "Operation Crossroads: Bikini Atoll" (https://web.archive.org/web/20130120201330/http://www.hist ory.navy.mil/ac/bikini/bikini7.htm). 1946. Archived from the original (http://www.history.navy.mil/ac/ bikini/bikini7.htm) on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2007. Specifically, Charles Bittinger (1946). "Rear Admiral William Sterling Parsons, USN" (https://web.archive.org/web/201211051222 01/http://www.history.navy.mil/ac/bikini/95129g.jpg). Archived from the original (http://www.history. navy.mil/ac/bikini/95129g.jpg) on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2007. 89. "Papers of William S. Parsons, Operational Archives Branch, Naval Historical Center, Washington, D.C." (http://www.history.navy.mil/research/archives/research-guides-and-finding-aids/personal-pa pers/p/papers-of-rear-admiral-william-s-parsons.html) Retrieved 17 October 2015. References Bird, Kai; Sherwin, Martin J. (2005). American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-41202-6. OCLC 56753298 (https://www.wo rldcat.org/oclc/56753298). Christman, Albert B. (1998). Target Hiroshima: Deak Parsons and the Creation of the Atomic Bomb. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-120-3. OCLC 38257982 (https:// www.worldcat.org/oclc/38257982). Furer, Julius Augustus (1959). Administration of the Navy Department in World War II. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. OCLC 1915787 (https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1 915787). Groves, Leslie (1962). Now it Can be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project (https://archive.or g/details/nowitcanbetolds00grov). New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-306-70738-1. OCLC 537684 (https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/537684). Hewlett, Richard G.; Duncan, Francis (1969). Atomic Shield, 1947–1952. A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0520-07187-5. OCLC 3717478 (https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/3717478). Hoddeson, Lillian; Henriksen, Paul W.; Meade, Roger A.; Westfall, Catherine L. (1993). Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943–1945 (https:// archive.org/details/criticalassembly0000unse). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521-44132-3. OCLC 26764320 (https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/26764320). Hunner, Jon (2004). Inventing Los Alamos: The Growth of an Atomic Community. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3891-6. OCLC 154690200 (https://www.worldca t.org/oclc/154690200). Lewis, Robert A.; Tolzer, Eliot (August 1957). "How We Dropped the A-Bomb". Popular Science. pp. 71–75, 209–210. Morison, Samuel Eliot (1948). Volume V: The Struggle for Guadalcanal, August 1942 – February 1943. Boston: Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 978-1612513188. OCLC 4091661 (https://www.worldca t.org/oclc/4091661). Shurcliff, William A. (1947). Bombs at Bikini: The Official Report of Operation Crossroads (https://a rchive.org/details/bombsatbikinioff00unit). New York: William H. Wise and Co. OCLC 1492066 (htt ps://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1492066). Retrieved 30 July 2011. Terrett, Dulaney (1953). The Signal Corps: The Emergency. Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army. OCLC 8990522 (https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/899052 2). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Sterling_Parsons 13/14 8/6/23, 1:30 PM William Sterling Parsons - Wikipedia Thomas, Gordon; Morgan-Witts, Max (1977). Ruin from the Air. London: Hamilton. ISBN 0-24189726-2. OCLC 252041787 (https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/252041787). Weisgall, Jonathan (1994). Operation Crossroads: The Atomic Tests at Bikini Atoll (https://archive. org/details/operationcrossro0000weis). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-155750-919-2. OCLC 29477984 (https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/29477984). External links Interview with Peggy Parsons Bowditch, daughter of Deak Parsons, about her father and growing up in Los Alamos (http://manhattanprojectvoices.org/oral-histories/peggy-bowditchs-interview) Voices of the Manhattan Project Arlington National Cemetery (https://ancexplorer.army.mil/publicwmv/#/arlington-national/search/r esults/1/CgdQYXJzb25zEgdXaWxsaWFt/) Retrieved from "https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=William_Sterling_Parsons&oldid=1168957103" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Sterling_Parsons 14/14