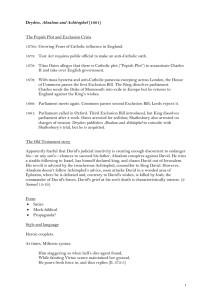

Research Paper Semper 1 Urna Semper Instructor’s Name Course Title 4 October 22 Report Name Satire is a type of writing whose stated goal is to reform human faults or vices via laughter or disgust. Though it is motivated by indignation, satire differs from scolding and outright abuse. Its goal is typically positive, and it does not have to stem from pessimism or hatefulness. The satirist examines men and women against particular ethical, intellectual, and societal norms to assess their level of crime or guilt. Satire has a wide spectrum by definition; it might be an assault on an era's vices, an individual's flaws, or follies common to the entire species of humans. Satire grew in popularity in England and throughout Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth century. Bodelaire, Moliere, and Voltaire from France; Richter and Heinefrom Germany; Swift, Pope, and Dryden from England. Cervantes from Spain. These satirists all had one thing in common with their Roman equivalents of antiquity: they all detested hypocrisy and turned insults into allegories. Research Paper Semper 2 Satire can be directed at a specific individual or at society as a whole. Genuine satire, on the other hand, never becomes so individualised that it loses interest to audiences other than the one it is targeting. Satire is more than just insults; it has the ability to change. Additionally, the personal assault must have a universal component in order to be creative. According to Augustine Birrell, the ultimate purpose of satire "is to lash the age, to mock foolish ambition, to expose deceit, to deride fraud in education, politics, and religion," and works by Horace, Juvenal, Dryden, Pope, Swift, and Samuel Butler all exhibit these traits. Political Satire Political satire examines politics in a lighthearted, sardonic, or sarcastic manner in an effort to highlight its absurdity and hypocrisy. Political satire, which combines comedy with political analysis, might lean more toward activism or toward making people laugh, depending on the subject matter and the satirist's intentions. Political satire can take many various forms, such as writing, editorial cartoons, and false news. Satire with a political bent is controversial since it may be perceived as anything from foolishness to being disloyal or even rebellious in some cultures. Dryden as a Satirist Before examining "Absalom and Achitophel" as a Political Satire, we must evaluate John Dryden as a satirist. Dryden distinguishes his satire with a focused and compelling lyrical language. Pope describes his satirical poem as having "the long majestic march and vigour heavenly." Critics have always praised Dryden's ability to elevate the banal to the poetical and turn personal enmity into the ferocity of artistic creativity. The convoluted and cryptic are clarified and made plain. The very first scene of Absalom and Achitophel displays all of this transforming power. The state of Israel is simple to comprehend, but Dryden has left out very little of the reality. Dryden demonstrates his mastery of both the Horatian and the Juvenalian satirical styles. He is powerful, incisive, urbane, and humorous, yet he is hardly ever petty. "Absalom and Achitophel" as a Political Satire Research Paper Semper 3 Dryden called Absalom and Achitophel 'a poem' and not a satire, implying thereby that it had elements other than purely satirical. For example, it is impossible to miss the clear epic or heroic overtones. However, as the poem was inspired by the political climate in England at the time, it is impossible to miss the fact that it satirises a number of important figures. The King gave Dryden the idea for the topic of the poem, which was then published in November 1681. The issue of King Charles's succession had grown quite important at this point. Due to a serious treason allegation, the Earl of Shaftesbury was imprisoned. The succession was being contested by two people. The first candidate was Charles's brother James, Duke of York, a well-known Roman Catholic; the second was the Protestant Duke of Monmouth, Charles's illegitimate son. The Whigs backed Monmouth, while the Tories backed James' cause to keep the kingdom stable. The question of succession caused considerable public dissatisfaction. King Charles II made sure that the Exclusion Bill—which was presented to Parliament and sought to bar his brother James' succession—could not be passed. An extremely ambitious man named the Earl of Shaftesbury attempted to take advantage of this turmoil. Additionally, he encouraged Monmouth to oppose his father. Even though he loved his illegitimate son, the King refused to endorse his succession since it would have been against the law. After being detained on a high treason accusation, the Earl of Shaftesbury lost favour from the public. Dryden wanted to help the King and expose his adversaries. Charles had his own flaws, of course; he had a strong attraction to women. But Dryden covers up his sexual misdeeds with a mask of charity. When it comes to his true vices, he is kind. The King himself did not have a negative opinion of his relationships. Because it was the norm for the time, sexual freedom should not be condemned. When it comes to the King's political moderation and his benevolence toward rebels, Dryden had nothing but praise. The adversaries of the King, notably the Earl of Shaftesbury, receive a whip from Dryden. He was an irresponsible, morally bankrupt politician who turned round and now drove down the stream after trying in vain to entice Charles to arbitrary government. Dryden fears the erratic nature of the mob and is unsure of the limits to which a mob may push itself. However, the King was able to establish the succession in accordance with his wishes because of his strictness and sense for the law. The adulation of the King and his belief in the "Theory of the Divine Right of Kings" are demonstrated by Dryden's allusion to the godlike David. Political Satire Cast in Biblical Mould In order to satirise the political climate, Dryden used the well-known Biblical tale of Absalom's rebellion against his father David at the evil urging of Achitophel. Although Dryden's use of a Biblical metaphor was not entirely novel, Courthope notes that the whole quality of his handling of the topic is unmatched. But throughout, Dryden takes care to ensure that the political satire is not obscured by a too complex Biblical allusion. Setting the narrative in pre-Christian days had the apparent benefit of giving Dryden an easy way out of a tricky dilemma where he had to simultaneously glorify the King and satirise the King's enemies. He had to emphasise Monmouth's illgitimacy in order to undermine his opponents, but he also wanted to make sure that Monmouth's father, Charles, was not negatively impacted by his remarks. He was unable to publicly support Research Paper Semper 4 Charles' poor morals while also unable to publicly criticize them. He arranges the poetry with a masterful touch "In pious times ere priestcraft did begin Before polygamy was made a sin, When man on multiplied his kind, Ere one to one was cursedly confined..." The satirical undertone is unmistakable, and Dryden is clearly giggling behind Charles' back—a smart patron who could neither miss it nor fail to find it amusing. Satirical Portraits of Political Personalities By choosing on a pre-Christian setting, Dryden was able to get beyond his initial challenge and was then free to criticise the King's sponsors and glorify his followers. He continues to accomplish this in a striking series of pictures that, although evolving from real people, achieve the universality of many personality types. In his portrayal of the rebels, Dryden makes full use of his collection of sarcastic tools. These sarcastic pictures are part of his larger plan rather than the consequence of personal hatred. ACHITOPHEL The poem's first and most prominent depiction is Achitophel. Here, lofty condemnation is the strategy rather than humour and subdued sarcasm. The Earl of Shaftesbury deserves stern treatment since he was a dangerous rebel. Thus, Achitophel represents both Shaftesbury as a specific person and Achitophel as a general term for all dishonest and cunning politicians. It is implied that Shaftesbury is a dishonest, vindictive, and unprincipled politician who is "resolved to ruin or rule the State." Dryden criticises Achitophel (or Shaftesbury) as the exact essence of wickedness, and his critique is ferocious and comprehensive. In order to paint Shaftesbury in a negative light, Dryden, with the freedom of a satirist, somewhat alters the reality. He claims that the rebel, by initiating the war against Holland, destroyed the Triple Alliance and prepared England for slavery. Shaftesbury is denounced as a dishonest politician who dresses up his self-serving goals in a guise of patriotism. The lines describing Shaftesbury's offspring — "that unfeathered, two-legged thing, born a shapeless lump, like anarchy" — are sharply satirical. Dryden's satirical style has a great amount of force. Shaftesbury is revealed to be a dangerous individual, but not one that Dryden's satirical might cannot contain. How can this man be trusted with a country, Dryden seems to be asking, if he is not wise enough to take care of his own frail body? If he were to become leader, the nation would undoubtedly fall into disaster due to the intellectual craziness in his nature. Here, satire is at its most potent; Shaftesbury is not the target of crude jabs, but rather, he is developed into a Satanic figure with a hint of lunacy, making the legitimacy of his fame questionable. Shaftesbury is the target of a moral assault that diminishes him without diminishing his capacity for evil. Research Paper Semper 5 ZIMRI When it comes to Zimri or the Duke of Buckingham, we do in fact have a case of what Dryden himself refers to as "fine raillery" — the act of cutting the head off from the body and leaving it standing in its place. The sarcasm directed towards Buckingham is mostly witty because he can be written off as a simple political amateur. He is less threatening and more meddlesome. The satiric technique of irony and sarcasm is well employed by Dryden in this depiction. The name selection couldn't have been more perfect because the Biblical Zimri is linked to treasonous schemes, sexual intrigue, and restlessness. We are taught that Zimri represented humanity since he was a "chemist, fiddler, statesman, and buffoon." The implication of grouping these four terms together is obvious—statesmanship Zimri's is essentially reduced to tinkering and buffoonery. He was a waste of money and easily fooled even by fools. He "left not faction, but of that was left" when his pathetic attempts to organise parties failed. He is a "madman" in whose restlessly inventive mind, "ten thousand freaks died in thinking". The image conveys a sense of hopelessness the entire time. The sufferer is reduced to being laughably incompetent, unworthy of serious thought, and an image of instability, energy wastage, foolishness, and clashing contradiction. Here, Dryden avoids using any abusive language. SHIMEI Shimei or Slingsby Bethel is portrayed with great satiric skill. The heroic couplet is fully utilised in order to demonstrate how well it lends itself to satiric anticlimax and the juxtaposition of opposites. When writing these words on Shimei, Dryden effectively used balance, antithesis, the pause, and surprise. The couplet starts out with what seems to be praise and the hope that the man has some redeeming qualities, but in each instance, it ends in disappointment or with a shock or surprise. Shimei never violated the Sabbath unless for selfish reasons. With the exception of against the government, he never made an oath. He displays fervour for God yet disdain for his monarch, who serves as God's emissary on earth. Shimei's pursuit of wrath, guile, and blasphemy demonstrates his fervour, intelligence, and piety. Shimei's abstentions, which are not a virtue but rather a manifestation of his greed, are insulted throughout the image with mocking laughter. Reading about his giving his chefs spiritual nourishment is hilarious. Dryden jokingly remarks that because he dared not to start even his kitchen fire, he was the ideal sheriff for a town that had once been devastated by fire. Shimei is unredeemable in any way. He is completely corrupt and utilises the laws he had promised to protect for illegal purposes. But aside from impiety and revolt, he is also something nasty, pinched, and cheap. In this instance, the satire takes use of a comic bathos. CORAH Contempt and disdain are used to paint a picture of Corah or Titus Oates. He is referred to as "monumental brass," which is a sign of his arrogance and conceit. The term alludes to Moses' savage snake, which rescued the Israelites, much as Corah will save England with his incredible lie. However, the word "brass" also connotes a brainless nature. Sarcasm and irony permeate the image. Dryden asserts in an ironic defence of Corah's modest birth that both a weaver's son and a prince are capable of great deeds. After all, a comet is born from atmospheric gases on Earth. Additionally, during Stephen's martyrdom, Research Paper Semper 6 no investigation into the lineage of the false witness, whose falsehoods led to the innocent person's execution, was conducted. Although Corah was a prophet who saw visions, he was also a false prophet. He talked as a prophet of future truths in cases when he was unable to use current facts (because they were not yet true). One cannot escape the irony. Corah is a deceptive, cunning, dishonest, and hypocritical person who is severely exposed by Dryden. These sentences, more than any other in the poem, reveal a nasty nature and employ blatant insult. For Corah, savage disdain and overtly offensive language are used, however the techniques are disguised by a clever play on words. The victim's crude physical description makes him despicable: he had sun eyes and a voice that wasn't loud or harsh, which were obvious signals he wasn't choleric or haughty (apparently enough, Dryden implied the opposite of what is stated.) Another derisive statement is that his long chin showed his cleverness. It's amusing how they mention his reddish complexion. He possessed the ability to recall incredible stories that no one could believe. His excellent judgement also fit the circumstances and the chances that were available. He was able to piece together several bits of proof to develop a plausible story. He even stated that he had earned a doctorate in divinity, although God only knows how Dryden's sarcasm could have taken him to such a lowly position. He gains nothing from his birth, his impudence, his false claim of public duty, the delusions he concocts from memory and judgement, or his cynical use of religious sanction for his own evil ends. He will share the same fate as the millions of other false witnesses. Although he has some redeemable qualities, he is too despicable to be regretted. ABSALOM Absalom (the Duke of Monmouth) is treated leniently by Dryden. He is presented rather as having been led astray by the clever Achitophel. Ambitious and restless, his wrong is not a crime: "It is juster to lament him than accuse". However, the presentation of Absalom is not totally devoid of ironical touches which are implicit rather than explicit in lines such as: "What cannot praise effect in mighty minds, When flattery soothes and when ambition blinds?" Tact demanded that Dryden should treat Absalom moderately. The satirist is subdued to subtle irony here. SATIRE AGAINST THE ENGLISH PEOPLE IN GENERAL. In his satire, Dryden does not hold back while mocking the English people as a whole. He makes fun of their mental instability, unstable thinking, and constant state of uprising. They are a stubborn, moody race that murmurs, making it difficult for any monarch to simply rule them during times of calm. Even God couldn't make them happy. Though they had ample freedom, they cried out for more. They are mocked by Dryden, who claims that they desired to live in a state of Nature like savages. Their unpredictable behavior is demonstrated by the warm greeting they gave the King and the following demand that he be exiled. They asserted that they had the authority to install and depose monarchs at will. Dryden makes fun of them by claiming that they are ruled by the moon, which at the time was thought to be the origin and cause of madness. He jokingly notes Research Paper Semper 7 that they change kings every twenty years. Dryden is aware of the conflicts, rivalries, and hypocrisies among various religious groups. All religious priests are the same. Because their gods provide them with a means of living, they would protect and revere them. Different faiths' priests are described as being greedy, self-centered, ambitious, and hypocritical. Conclusion The most ferocious and well-polished of English satirists, Dryden successfully combines finesse and ferocity. In "Absalom and Achitophel," Dryden demonstrates his unmatched skill at reasoning in poetry. In terms of political satire, "Absalom and Achitophel" is without a doubt the best. The poem's attraction to the current reader stems from its insights on English character and the flaws of men in general, aside from its historical significance and present importance. His broad generalisations about human nature have enduring appeal. Dryden overcame the unusual challenges presented by his subject of choice. Not abuse or politics, but the poetry of abuse and politics, was what he had to give. He had to criticise a son whom the father still liked; he had to make Shaftesbury denounce the King but he had to see to it that the King's susceptibilities were not wounded. He had to criticise aesthetically but also praising without appearing slavish. All of this is accomplished by Dryden deftly and skillfully. In Charles's eyes, Achitophel's criticism of the King takes on the hues of a praise. Achitophel is using Absalom as a misdirected tool. The poem is undoubtedly political satire, yet it manages to combine dignity with biting and effective criticism.