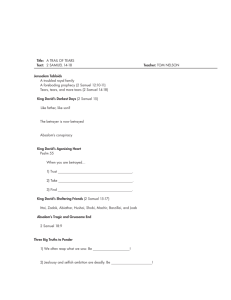

The Popish Plot and Exclusion Crisis

advertisement

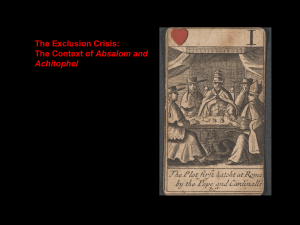

Dryden, Absalom and Achitophel (1681) The Popish Plot and Exclusion Crisis 1670s: Growing Fears of Catholic influence in England. 1673: Test Act requires public official to make an anti-Catholic oath. 1678: Titus Oates alleges that there is Catholic plot (“Popish Plot”) to assassinate Charles II and take over English government. 1679: With mass hysteria and anti-Catholic paranoia sweeping across London, the House of Commons passes the first Exclusion Bill. The King dissolves parliament. Charles sends the Duke of Monmouth into exile in Europe but he returns to England against the King’s wishes. 1680: Parliament meets again. Commons passes second Exclusion Bill; Lords rejects it. 1681: Parliament called in Oxford. Third Exclusion Bill introduced, but King dissolves parliament after a week. Oates arrested for sedition; Shaftesbury also arrested on charges of treason. Dryden publishes Absalom and Achitophel to coincide with Shaftesbury’s trial, but he is acquitted. The Old Testament story Apparently fearful that David's judicial inactivity is creating enough discontent to endanger his—or any son's—chances to succeed his father, Absalom conspires against David. He wins a sizable following in Israel, has himself declared king, and chases David out of Jerusalem. His revolt is advised by the treacherous Achitophel, counsellor to King David. However, Absalom doesn’t follow Achitophel’s advice, soon attacks David in a wooded area of Ephraim, where he is defeated and, contrary to David's wishes, is killed by Joab, the commander of David's forces. David's grief at his son's death is characteristically intense. (2 Samuel 13-19). Form Satire Mock-biblical Propaganda? Style and language Heroic couplets. At times, Miltonic syntax: Him staggering so when hell’s dire agent found, While fainting Virtue scarce maintained her ground, He pours fresh force in, and thus replies (ll. 373-5) 1 Look out for the language of angels and demons. Dryden is clearly influenced by Milton’s Paradise Lost, which he greatly admired. Some by their friends, more by themselves thought wise, Oppos'd the pow'r, to which they could not rise. Some had in courts been great, and thrown from thence, Like fiends, were harden'd in impenitence. (ll. 142-5) Achitophel is persuasive. Like Milton’s Satan, on whom he is modelled, he is a dangerously powerful orator. Dryden critiques the rhetoric of Whiggism not by openly ridiculing it but rather by showing his reader just how disturbingly seductive it is – the way it renders revolution palatable: All empire is no more than pow’r in trust: Which when resum'd, can be no longer just. Succession, for the general good design’d, In its own wrong a nation cannot bind: (ll. 405-14) Compare this to the way King David speaks at the close of the poem: That one was made for many, they contend; But 'tis to rule; for that's a monarch's end. They call my tenderness of blood, my fear; Though manly tempers can the longest bear. Yet since they will divert my native course, 'Tis time to show I am not good by force. (ll. 945-50) Also look out for the language of bodies. Beauty and ugliness have political charge. Absalom is beautiful; Achitophel, in contrast, is deformed: A fiery soul, which, working out its way, Fretted the pigmy-body to decay, And o'er-informed the tenement of clay. (ll. 156-8) … Got, while his soul did huddled notions try; And born a shapeless lump, like anarchy. (ll. 171-2) Drama Dryden was a prolific and successful dramatist. In 1674 he published The State of Innocence and The Fall of Man, a dramatic adaptation of Paradise Lost. Absalom and Achitophel is a highly dramatic poem. Look at the way Dryden constructs dialogue, speeches (Absalom essentially offers a soliloquy), and even stage directions. Is this a panegyric? Is it propaganda? What faults he had (for who from faults is free?) His father could not, or would not see. (ll. 35-6) 2