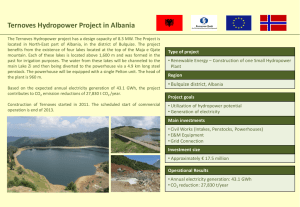

1 Home My Network Jobs Messaging Notifications Edit article View stats View post ▲ One of the two hydroelectric power plants in Asahan hydropower plant No.2 Tangga Hydropower plant. Photo/JSCE From Asahan River to Kayan River: Reflections on Driving Industrial Upgrading in Indonesia through a River Xi Deng Green Energy, EV, Circular Economy, Mining... To do well, to do good, to feel good! 3 articles July 12, 2023 This year marks the 40th anniversary of the operation of the Asahan Aluminum Smelter Plant (Inalum). Located in North Sumatra, this project was the largest investment by Japan in Southeast Asia at that time and the first aluminum smelter plant (225,000 tons/year) in Me For Business Get Tr the region. It was accompanied by two cascade hydropower plants built on the Asahan River: the Asahan Hydroelectric Plant No.2 (with a total installed capacity of 603 MW). This project represented an important attempt to secure raw material supply for Japan, and drive resource-based industrialization in Indonesia’s perspective, with certain lessons to be learned for similar future projects. ▲ The catalytic effect of The impact of the Asahan aluminum smelter on downstream & related industries in North Sumatra appears limited.Photo/Inalum According to an announcement on the official website of the Indonesian Presidential Office, on February 28th of this year, President Joko Widodo visited the Kalimantan Industrial Park (KIPI) and introduced to the press the park's plans to incorporate three major industries: EV batteries, petrochemicals, and aluminum smelters. The aim is to develop KIPI into the world's largest green industrial park, which represents the future of Indonesia. By utilizing green energy, renewable energy, and hydropower from the Kayan and Mendarang Rivers, the products from this park will also be environmentally friendly. If properly developed, it is expected to attract various industries and investments. ▲ Pres. Jokowi: KIPI Industrial Park is all about going green. Photo/Sekretariat Presiden. Can the hope for industrial upgrading and regional development in Indonesia rely on just one river? As per the plan, to provide reliable green energy to the KIPI, which focuses on industries such as lithium-ion batteries, petrochemicals, and aluminum smelters, hydropower is currently the only viable option. The power demand for the petrochemical industry is not significant. For example, a large-scale petrochemical project with a refining capacity of 10 million tons and an ethylene production capacity of 800,000 tons would require a conventional coal-fired power plant with a capacity of around 100 MW. The major electricity consumers would be the lithium-ion battery manufacturers and aluminum smelters. For instance, producing one ton of aluminum requires approximately 14,000 kWh of electricity, so an annual production capacity of 500,000 tons would need 7 billion kWh of electricity. This would require a largescale hydropower plant with a capacity of over 1,000 MW, along with corresponding solar power plants with an installed capacity of approximately 6,000-7,000 MW, occupying an area of 10,000 hectares (KIPI's planned area is about 13,000 hectares). Additionally, energy storage facilities would also need to be implemented. The previous hope for industrial upgrading and regional development centered around the Asahan aluminum smelter project on the Asahan River. ▲ The upstream of the Asahan River is Lake Toba, which has a surface area of 1,130 square kilometers. Photo/JSCE ▲ The Sigara-gura hydropower plant (286 MW) is one of the cascade hydropower plants in the Asahan 2 Hydropower Project. Photo/JSCE However, it seems that the Asahan Aluminum Smelter Plant has not had a significantly catalytic effect on the downstream industries in Indonesia or the development of related industries in North Sumatra: The lack of a sizable industrial base undermines the pioneering role of the Asahan Aluminum Smelter Plant. Large-scale industries account for a low proportion of North Sumatra's GDP, with the region's industries mainly focusing on mining, palm oil, and oil extraction, which are not directly related to aluminum products and do not complement them. The plant's impact on the upstream and downstream industries in North Sumatra is not significant. The downstream industries of the aluminum smelter plant include various aluminum fabrication plants, and consumer markets (such as rail transportation, construction, automotive, and power sectors), which are primarily concentrated in Java Island, where there is a large pool of skilled labor and convenient transportation. Transportation requirements for finished aluminum products (such as aluminum alloy frame for doors and windows) are much higher than those for aluminum ingots, which limits the clustering of downstream enterprises in North Sumatra. Similarly, due to poor inland transportation in Kalimantan, the alumina enterprises concentrated in West Kalimantan need to rely on maritime transportation to deliver their products to the aluminum smelter plant in North Kalimantan, which may incur higher transportation costs compared to those to West Java. The focus is on local resources rather than demand. It is said that the Asahan Aluminum Smelter Plant was located in North Sumatra because of the abundant and economically viable hydropower resources in the Asahan River, thanks to the presence of Lake Toba, Indonesia's largest lake. However, the project did not consider whether North Sumatra itself was qualified to be the hub radiating to the upstream and downstream of the aluminum industry chain. This decision was mainly based on the local resources without considering the demand side, as the alumina raw materials were imported from Australia, and 60%-66% of the produced aluminum ingots were exported out of Indonesia. The employment effect is not significant. Throughout the 9-year construction period, only 12,000 workers were hired, and the operational phase of the aluminum smelter plant employed just over 2,000 people. With an investment of $1.6 billion, the project created temporary employment for over 12,000 people and long-term employment for just over 2,000 people. To achieve the desired effects of a "resource-based industrialization" as a strategy for economic growth, the pioneer industry either should not be of a large scale or should be located adjacent to a core economic area to benefit from the agglomeration economy or integrate into it (Richardson & Richardson, 1975). Hydropower, it's not easy to say "I love you" ▲ On January 18, 2014, the groundbreaking ceremony for the Kayan Hydropower Plant (6080MW) took place. Photo/Xi Deng The Mendarang Induk Hydropower Plant (1375MW) is a joint development between Sarawak Energy, the sole electricity company in Malaysia's Sarawak state, and Adaro, the Indonesian coal mining giant. Considering the situation of the industrial estate and the hydropower plant, the following observations can be made: Power demand is not strong. Hydropower accounts for 77% of Sarawak Energy's energy mix, which is their banner and image. Sarawak Energy's hydropower expansion strategy seems to be more supply-driven rather than demand-driven. Sarawak Energy currently has an installed capacity of 5,646MW (additional capacity from the ongoing construction of Kidurong Combined Cycle Power Plant with 842MW and Baleh Hydropower Plant with 1,285MW scheduled for 2023 and 2027, respectively) and has already signed power purchase agreements (PPAs) for 2,930MW, resulting in a seemly oversupply. Adaro and Sarawak Energy's hydropower joint venture company would need to sign PPAs with the KIPI or the aluminum smelter to secure financing. The aluminum smelter is reportedly set to start operations in 2025, while the hydropower plant will take another ten years to become operational. Engineering the PPA agreement will require some effort. Adaro is unlikely to allow Sarawak Energy to participate in the revenue share from aluminum sales, so Sarawak Energy's source of profit would only be the hydropower plant (Sarawak Energy currently sells electricity at an average price of around 5.9 US cents). Additionally, the three major industries to be introduced to KIPI do not possess the inherent driving force and external conditions that facilitated the development of the stainless steel industry in the Morowali Industrial Park. Therefore, the industrial park would likely require significant effort to attract these industries. Hydropower generation costs may be higher. Aluminum smelting is an energy-intensive industry and is highly sensitive to energy costs, with electricity costs accounting for 30%-40% of aluminum production costs. For an aluminum smelter with an annual capacity of 500,000 tons, a difference of one cent (1/100 U.S. Dollar) in electricity price amounts to 70 million US dollars in electricity expenses. Looking at the PLTU Jawa 5 and PLTU Jawa 7, two 2x1000MW ultra- supercritical coal-fired power plants in Indonesia, the electricity tariff (for the first ten years) can be as low as 4.2 US cents/kWh. If Adaro uses its own coal mines in Kalimantan to build coal-fired power plants at the mine mouth, the generation cost can be lower than 4.2 US cents/kWh. In comparison, the current ceiling tariff for large-scale hydropower projects by Indonesia's state electricity company (PLN) is 7.41 US cents/kWh for the first ten years (in the Kalimantan region) and 4.21 US cents/kWh for the subsequent twenty years (Why such a large difference in electricity prices? Because large-scale hydropower projects involve long construction period and significant investments, the electricity price is higher in the first ten years, which is favorable for independent power producers to repay loans). Furthermore, there is a considerable possibility of potential cost overruns for large-scale hydropower projects (the hydropower plants associated with the Asahan aluminum smelter had a cost overrun of 31%). For comparison, in Yunnan, China, which is the world's largest base for hydropower-based aluminum smelters, the government supplies electricity at a price of 0.25 RMB/kWh (approximately 3.5 US cents/kWh), and there is no need to build their own hydropower plants. High requirements for the operation and management of hydropower plants and the power grid. On the evening of June 27, 2013, Sarawak Energy's power grid experienced a blackout, resulting in the temporary shutdown of all five power plants under its control. This incident also caused damage to the electrolytic cells of Press Metal Bhd's Mukah aluminum smelter, the largest aluminum smelter in Southeast Asia, leading to a five-month production halt (with an additional four months to restore production capacity- Press Metal's 2013 financial report). It was preliminarily determined that the tripping of three units at the Bakun Hydropower Plant resulted in an unexpected drop of power supply of 650,000 kilowatts. Hydropower plant construction takes a long time. Just across the border, there are two hydropower plants in Sarawak with similar installed capacity and dam types: the Bakun Hydropower Plant (2400MW) and the Baleh Hydropower Plant (1285MW). The former took 9 years to complete, while the latter started construction in 2017 and is expected to be completed in 2027 (comparable coal-fired power plants with similar installed capacity take 4 years to construct). The long construction period is due to significant opportunity costs, as capitalists understand the principle of early production for early returns. Additionally, there is a high level of uncertainty due to the significant impact of global market (the Asahan aluminum smelter project took 9 years to complete and experienced significant losses due to fluctuations in international aluminum prices and a sharp appreciation of the Japanese Yen). Low power stability. Industries such as aluminum smelter have high requirements for stable and reliable power, raw materials, and production. Without a robust power grid and other power sources for regulation and backup, smelter or industrial park that rely solely on a direct-supply of hydropower, which naturally exhibits seasonal flow fluctuation, may face low reliability. The Asahan aluminum smelter's associated hydropower plants consist of two stages (two hydropower plants) and benefit from the presence of Lake Toba, Indonesia's largest lake, which provides multi-year regulation capabilities (the Asahan River has a large flow, and as a result, the Asahan No.1 and No.3 hydropower plants were subsequently built. Even though, a decrease in Lake Toba's water level from the second half of 1987 to early 1988 resulted in reduced production of the smelter). Regarding the KIPI's aluminum smelter and its accompanying hydropower plant, several key points can be identified: Prioritize the construction of coal-fired power plants. Currently, with Adaro's investment-grade credit rating (BBB-), as long as they can obtain loans or issue corporate bond, the electricityintensive aluminum smelter plant is likely to use coal-fired power. The development of hydropower will proceed step by step, and at this stage, hydropower can only play a role in promotion and persuasion for financing institutions and stakeholders (it is also a practical need for listed companies to achieve ESG performance, which applies to Sarawak Energy as well). The aluminum smelter plant may not be necessarily located within the KIPI. West Kalimantan and Bintan of Riau Islands are gathering places for bauxite, the raw material for aluminum, and are also production bases for alumina, the immediate feedstock for aluminum. By claiming that the aluminum smelter will be located in the KIPI and will use green hydropower in the future, it might be easier for Adaro to facilitate financing for the coal-fired power plant in the guise of future green energy. If Adaro can secure loans for the coal-fired power plant, they may choose a location close to both the coal mine and the alumina plant, where land acquisition is easier, to build the aluminum smelter plant. The Mendarang Hydroelectric Power Plant may become part of Sarawak and Sabah power grids. This might be the starting point for SEB's investment in the hydropower plant. Currently, Sarawak Energy is working on interconnecting the power grids of Sarawak and Sabah, and then connecting them to the power grid of Kalimantan (transmission to West Kalimantan was already established in 2016), gradually achieving the integration of the Borneo power grid and ultimately realizing the strategic goal of becoming the "battery of ASEAN." This approach not only benefits the improvement of power quality for major power consumers within the network, including the KIPI aluminum smelter, but also facilitates power consumption. Immigration and land acquisition as well as environmental protection should not be underestimated. Firstly, as an energy-intensive project, aluminum smelters attract attention and differ from Adaro's low-profile coal mining operations. Secondly, the joint development of Southeast Asia's largest hydropower station involves large concrete-faced rockfill dam (requiring extensive local excavation of dam fill materials), coupled with their large reservoir capacity (resulting in significant submerged areas) and location in tropical rainforests, as well as the presence of traditional longhouses belonging to the Dayak indigenous people, are all key factors that resonate strongly with NGOs and environmentalists. IN CONCLUSION, Electrolytic aluminum production is among the highest contributors to carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in the metallurgical industry. With its reliance on coal-fired power plants for electricity, the aluminum smelting process emits approximately 11-13 tons of CO2 per ton of aluminum produced. In contrast, hydropower has nearly zero emissions. In the context of carbon reduction and various specific policies such as the EU carbon tariffs, it becomes more meaningful to use clean energy sources for powering electric vehicle batteries. Despite the significant challenges involved, the development of low-carbon and green energy sources such as hydropower, wind power, and solar energy is a trend and a future necessity. Perhaps, this is what President Joko Widodo meant when he emphasized that the KIPI is the "future of Indonesia." Published by Xi Deng 3 Green Energy, EV, Circular Economy, Mining... To do well, to do good, to … articles Published • 3m My write-up examines the challenges faced in Indonesia's industrialization process through a retrospective analysis of the Asahan project. It highlights issues such as electricity demand, generation costs, grid management, and carbon emissions. These challenges require collective efforts from the government, businesses, and related stakeholders to address them and promote sustainable development and green industrialization. Like Comment Share 0 Comments Add a comment… Xi Deng Green Energy, EV, Circular Economy, Mining... To do well, to do good, to feel good! More from Xi Deng Dreams of the Indonesian High-Speed Rail: Experiences and… Will the Indonesian nickel industry win big again in the wave of new energy ? Xi Deng on LinkedIn Xi Deng on LinkedIn