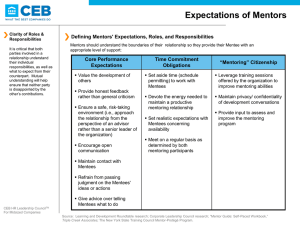

To: Sarah Hodgeson From: Junior Attorney Date: July 22nd, 2023 Re: Matter of I.B.I. This memo address changes to I.B.I.’s Agreement with Business Mentors. The goal is to clarify the relationships between I.B.I., its mentors, and its mentees. We want to protect the mentees from unfair relationships by enabling contractual claims as third-party beneficiaries and establishing fiduciary obligations with a confidential relationship. 1. Fiduciary obligations owed by mentor to mentee arising from the I.B.I. Mentorship Agreement. Mentors may become obligated to mentees when a fiduciary relationship is established between them. The Agreement can be used to create such a relationship. This relationship would exist outside of contract law, enabling mentees to raise claims not specifically defined by a contractual term, but rather a duty. a. The Togs rule: liability apart from contractual obligations. Togs involved Children’s Clothing Manufacturer (CCM) and Togs for Tots (Togs), a corporation that markets children’s clothing to retailers. This relationship began in 2001 when Painter (Togs) approached Denito (CCM) with a proposition for Denito to create CCM so Painter could sell their clothing. Painter held himself out as a partner of CCM while advertising their clothing. Painter and Denito made all business decisions together, with each controlling the activities of their respective companies. Stepping outside this arrangement, around 2009, Painter helped design a unique line of clothing in order for CCM to secure its biggest client, Walmart, worth $12m of their $15m in gross sales. Then, in 2009, CCM terminated their relationship with Togs. Togs filed for breach of contract and separately that CCM breached a duty owed to them from a confidential relationship. The trial court dismissed the breach claim but not the later. The appeals court confirmed. The appeal to the Columbia Supreme Court concerned the fiduciary duty. b. Ways to create a fiduciary duty The Court established that a breach of fiduciary duty claim exists when a plaintiff proves three elements: (1) a fiduciary duty, (2) defendant breached the duty, and (3) damages were proximately caused by the breach. A fiduciary duty may be proved in two ways: a recognized relationship or “confidential relationship.” i. Recognized relationships Recognized relationships are those like agent and principal, trustee and beneficiary, or guardian and ward. I.B.I. is not seeking to establish one of these with their Agreement. ii. Not standard, “confidential relationships” established as matters of fact A confidential relationship cannot be proven as easily. They must be inferred from the circumstances and relationships between the parties. 1. Reliance and dominance are key factors In Togs, the Court found that reliance and dominance of the party alleged to owe the fiduciary duty are most important factors. They can be shown when there is “reliance because of a history of trust, older age, family connection, and/or superior training and knowledge.” The question is whether the differences create an inequity that imposes duties. Ultimately, the Court in Togs held the trial court should have dismissed the claim based on a confidential relationship and a resulting fiduciary duty. 2. Not for “everyday commercial activity” The Court also discussed that typical relationships do not create these relationships. In Shaw, the court found no such relationship. The plaintiff in that case sued for unpaid commissions and the defendant counterclaimed for a breach of a confidential relationship. There was no such relationship because the parties’ relationship was based on a bargained for exchange, everyday commercial activity, rather than a non-contractual relationship involving commercial activity and a power imbalance. c. Recommended changes Togs demonstrates the importance of making clear that mentors have “substantially greater knowledge, expertise, or financial resources than the other [party]” and lack of “a history of bargained-for collaboration.” Id. These lessons can be incorporated in the Mentorship Agreement. i. Make the relationship and imbalance clear I.B.I. should add a term that the mentor agrees to explicating that the mentor acknowledges that have superior knowledge and expertise than the mentee. The implications of this, in line with Togs, should be explicated. Understanding when liability could be created should alleviate mentor’s concerns by guiding them away from potential conflicts. ii. Explicitly warrant this this is not an “everyday commercial activity” In addition to the term cautioning against fees and gifts, mentors should be cautioned against engaging in any kind of commercial activity with their mentees. This will prevent the formation of obligations that may harm parties and keep their relationships informal. iii. Caution against bargained for exchanges I.B.I. should dissuade parties, but perhaps not prohibit them, from collaborating with their mentees. Such an agreement would muddy the relationship and enable disagreements. This would protect mentees by putting them on notice that the power imbalance in a mentorship could result in unexpected difficulties. It would also alleviate the concerns of mentors by letting them know how they can shield themselves from liability – do not enter into contractual relationships if there is any doubt about their fairness. This should include language cautioning against recommending services other than the mentor’s, such as a business partner or family member. 2. Contractual rights that I.B.I. mentees can assert as third party beneficiaries Mentees can also hold mentors liable inside contract as third-party beneficiaries. The Mentorship Agreement is signed only by I.B.I. and the mentors, but the Agreement is explicitly for the benefit of the mentees. This is likely to create a third-party beneficiary situation, which has implications worth considering and discussing in the Agreement. a. Fiduciary duties versus contractual obligations Contractual relationships create obligations by objective agreement between the parties. In contrast, fiduciary duties arise out of less clear relationships that may not include consideration or be directly aimed at commercial activity. Thus, when I.B.I. wishes to create contractual relationships it is important to establish the components of such an agreement in a way that all parties understand. b. Norton: Who is a third-party beneficiary? Norton is a Columbia Supreme Court case that concerned a non-profit spiritual retreat’s agreement with its spiritual leader. About 20 “resident members” of the organization sued as third party beneficiaries claiming that the leader, Samuel Kramer (AKA Joseph Morgan), misled them about his background such that he breached a contractual obligation owed to them. They argue that since the non-profit used Morgan as an advertising figure and leader, in a way that provided life advice and mentorship, but this was based on lies about Morgan’s background (and name) so severe that the inducement by this advertisement was fraudulent. This, they argued, breached a contract in which they were third-party beneficiaries (among other arguments). This argument was dismissed by the trial court and later that dismissal was affirmed by the Columbia Supreme Court because it failed to state a claim for breach of the contract between the non-profit and Kramer – there was no term they could point to that had been breached. However, the resident members succeeded in establishing a third-party beneficiary relationship, and studying this helps I.B.I. understand what changes they should make to their Agreement. i. Intent matters most The “key question” is whether there was intent to benefit a third party in the contract. “The intent must appear from the contract itself or be shown by a necessary implication.” Norton. The Court found that the residents could establish a third-party beneficiary arrangement by showing Kramer contracted with the non-profit retreat for valuable consideration to provide services to the residents. The contract did establish this relationship. It set requirements for Kramer, such as attending the retreat and teaching yoga courses. But because the contract did not contain terms suitable the resident’s purposes in the lawsuit, their argument the Kramer breached because he was not “authentic” and reaped substantial profits could not win. The Court suggested that the residents could have won had the contract limited the financial benefits to Kramer or held him to a particular standard of behavior. Id. c. Recommended changes Norton provides several lessons for I.B.I. that they can implement in the Agreement. i. Make intent to benefit mentees clear I.B.I. should add a term specifically mentioning that a third-party beneficiary relationship will be formed when a mentor signs the agreement. This ensures protection for mentees. Further, it should encourage mentors by removing doubt about what sort of relationship they have with their mentee. This could lessen the informality of these relationships, but since it does not create more obligations than have already been implied, creating explicit contractual duties should not be too burdensome. ii. Create specific terms that mentees can raise claims under In Norton, the non-profit and Kramer could not be held accountable for their allegedly misleading conduct under contract law because there was no term specifically agreed to that the members could point to as having been violated. I.B.I. can avoid a similar problem by deciding carefully about what sorts of behaviors mentees should be able to sue over. A beginning to this would be prohibiting misleading mentees or engaging in fraud. 1. Code of conduct A code of conduct, like one implied by a fiduciary duty, can be explicitly assumed by mentors. I.B.I. would be wise to consult business experts about what code is most appropriate for this situation. 2. Behavior Specific behavior, like perhaps self-interested dealing or unconscionable charges, can be explicitly prohibited, enabling mentees to challenge the behaviors of their mentors.