Uploaded by

M Mohsin Chowdhury (Mohsin)

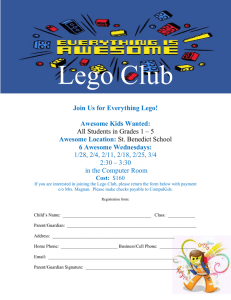

LEGO®-Based Therapy: Building Social Skills with LEGO® Clubs

advertisement