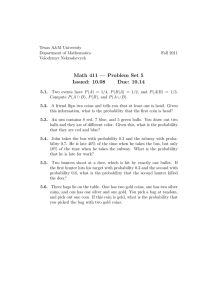

SOME NOTES ON RELIGIOUS EMBODIMENTS IN THE COINAGE OF ROMAN SYRIA AND MESOPOTAMIA PHILIPP SCHWINGHAMMER Introduction The following paper is about some religious embodiments of coins minted in Emesa, Palmyra, Hierapolis , Edessa, Hatra and Anthemusia. I’ll focus my attention on the typology and manner of representation of Ancient Arabian deities, especially on the typology of the city goddess Tyche. My point of view is that the most important aspect of describing an Ancient Arabian god is to take every detail of the whole image into consideration and try to interpret the manner of representation. Small parts of the embodiment, such as stars, eagles, lions, torches and crescents have to be seen as attributions for any particular deity. Ancient Arabia has a wealth of different deities which could be syncretized in their religious function to common Greek and Roman Gods. It represents one of the most impressive theotechnies of ancient times. Lunar symbols like crescents and bulls, solar symbols like radiate busts, lions and suns, and astral symbols are in a typological way pars pro toto for the moon god Sin / Aglibol, sun god Shamash / Shams / Yarhibol and the astral deity of Inanna / Ishtar / Atargatis. Looking at the geography of Syria and Mesopotamia we are able to recognize a large geographical complex which is bounded in the North by the Taurus and Antitaurus mountains, in the South by the Red Sea, the Negev desert and the beginning of the Arabian Peninsula, in the West by the Mediterranean Sea and in the East by the syro–mesopotamian landscape with its deserts and of course by the river systems of Euphrates and Tigris, the natural border of Syria and Mesopotamia. This natural area with its geographical determinate settlements is unique and is called the ‘fertile crescent’ because of its special agricultural use; it’s a bigger area, including the Persian Gulf to the Northern parts of Syria through the Levantian coast to Israel. The Ancient Arabian society was multilingual.1 We are able to differentiate between High-variety languages and local dialect forms, called Low-variety. An H-variety language was a language which could be understood throughout its local borders and which was important for economic reasons. In Northern Arabia, from the first century BC until the third century AD, Latin and Greek were the most important functional languages having regard to the H-variety criterion. Latin was the main linguistic instrument of the European world as the language of the Roman Empire, and Greek in its meaning as Koine Greek was very important for the economic links between the Western and Eastern civilizations. Also Aramaic as the strongest local language had H-variety status. But its dialectically different forms spoken in the urban centres (such as Petra, Palmyra, Hatra, Edessa and Emesa) were documented in the epigraphic sources and have to be seen as L-variety because of their limited local use. These urban centres were similar to the poleis of the Greek world whose terminology is reflected in the meaning of desert cities / oases. Because of the geographical situation most of these cities were built on rivers, coasts, lakes and oases and became important economic trade points in the Near Eastern world regarding the caravan trade. After the decline of the Seleucid Empire in the first century BC there was a large vacuum of 1 Sommer 2005, pp. 115 ff. 2 PHILIPP SCHWINGHAMMER power which allowed certain cities on important trade routes to gain their economic independence. These more or less independent cities are documented in lots of regionally found inscriptions. The caravan trade is a central factor of daily life, so small independent empires, such as Edessa or Palmyra, were able to make a great deal of money by regulating prices and quantities on these trade routes. They were controlled by a central power in a political way, but they had a degree of economic independence. The coinage of Emesa The sacrificium of Emesa is a temple which is dedicated to Heliogabal, whose name means god of the mountain, el gabal. He is the local sun god and the holy stone in his temple reflects his power and his name. On coins of Emesa we see temples with and without holy stones, eagle figures and combinations between eagle and the lithartic object. The holy stone in its function as a lithartic element is pars pro toto of the temple itself and along with the eagle as solar symbol is generally associated with the sun god, shamash / shams or his equivalent in Emesa, Heliogabal. This means that we have in this case, with regard to the reverse typology, a syncretism between the eagle-holystone combination and the sun-god heliogabal. Also in the names of the emperors of Emesa we find some onomastical parts which refer to the sun-god or to the sacrificial stone itself, like Samsigeramus (the sun-god has decided), Iamblichus / Yamlik-el (The law of god) and Sohaemus (black/precious stone).2 Emesa related to the holy stone some kind of a pilgrimage city and additionally to that a religious city state of Ancient Arabia. The local kings have not figured greatly in the coinage, like in Edessa and Palmyra. However, the local sun cult, as well as the moon star cult from Carrhae / Harran and the Atargatis cult of Hierapolis, have to be mentioned as part of the daily religious life. The first coin I want to present is a tetradrachm (Pl. I, 1) of Caracalla. The obverse contains a laureate draped bust to the right with the legend AVT K MAYP – ANTONINOYC C and the reverse a hexastyle temple with a holy stone inside with the legend ЄMISWN – KOΛONIA (Baldus 35). The second coin is a didrachm of Caracalla (Pl. I, 2) which shows on the obverse a laureate bust to the right with the legend AVT K MA – ANTONINOYC C and on the reverse an eagle frontal standing with spread wings and a small wreath in his mouth, beneath the bust of the sun god Heliogabal to the left with the legend ΔHMAPXIA YΠATOC TO Δ. The eagle is a solar symbol and represents the sun god. The third coin is a tetradrachm of Caracalla (Pl. I, 3) which embodies on the obverse a laureate bust to left with the legend AVT K MAYP – ANTONINOY – CC and on the reverse an eagle frontal standing with spread wings and a small wreath in his mouth, sitting on the top of the holy stone, and in the field right Z K Φ (527 Seleucid Era = 215/216 AD) and ЄMISWN – KOΛONIA (SNG Cop. 310). The combination of eagle and holy stone gives also a linguistic hint referring to the name of Heliogabal (god of stone) and its solar attribution the eagle. The coinage of Hierapolis The city of Hierapolis is very important for its Atargatis cult. Regarding the coinage of Hierapolis we can recognize two different types of religious reverse embodiments. The first coin (Pl. I, 4) is a bronze coin of Lucius Verus on the reverse of which we see a bull under a crescent. Both are symbols for the moon god Sin. The second coin (Pl. I, 5) shows us on 2 Sommer 2005, pp. 116 ff. SOME NOTES ON RELIGIOUS EMBODIMENTS IN THE COINAGE OF ROMAN SYRIA AND MESOPOTAMIA 3 the reverse a city goddess with a torch, riding on a lion. Both symbols are of solar nature, the torch in its function as source of light and the lion which from the front has hair reminiscent of sun radials. So the city goddess is totally a solar attributed figure and a sun god in its function as a city god. The coinage of Palmyra The autonomous copper coinage of Palmyra is in its religious intention overwhelming. Its interpretation is very important for the understanding of religious life in Palmyra itself. At this point I must mention the research papers of Aleksandra Krzyzanowska3 and Ted Kaizer4 which deal with the typology of Palmyrenian copper coins and the reason for minting. If a political power in the oriental concept is identical with its religious authority, the propagandistic intention of political elites embodies religious ideas, cults and rites, wherewith a state identifies, through a mass medium like the coin. The reason for minting coins in Palmyra was, as I assume, neither manifested in the political propaganda nor in economic political grounds, because these coins from this point of view do not have any importance. It is rather the prestige of the city itself in producing its own coins without illustrating the central political power of Rome on the pieces and to emphasise the local propagandistic influence. The embodiments show on both sides gods, religious scenes and symbols rather than portraits of local and Roman authorities. I want to present three examples of this anonymous coinage. All pieces have a weight of 5 g and a diameter of about 1.5 cm. The first one (Pl. I, 6) shows on the obverse a bust of the city god to the right and on the reverse a caduceus with crossed cornucopiae; the second one (Pl. I, 7) a bust of Pallas Athene on the obverse and a palm tree as a symbol of a caravan city on the reverse (the palm tree has to be understood as a graphic illustration for the city itself); and the third coin (Pl. I, 8) has on the obverse Nike standing to the right, holding a palm branch in front of an altar, and the frontal bust of Malakbel with globe hairstyle, flanked by the busts of the sun god and the moon god, Aglibol and Yarhibol, on the reverse (Krzyžanowska I). Because of the anonymous character of these coins it is rather hard to date them exactly, but having regard to their style I would tend to date them in the period between the middle of the second century and the middle of the third century AD. The coinage of Anthemusia The mint of Anthemusia is a small one near Carrhae and I want to introduce two examples of religiously inspired coins. The first one shows (Pl. I, 9) the laureate bust of Caracalla with paludamentum and cuirass to the right on the obverse, and the bust of the moon god with some kind of a crescent-diadem to the right on the reverse (BMC 2 var.). The second coin (Pl. I, 10) is a bronze coin of Elagabalus which embodies on the obverse the radiate bust to the left and on the reverse the bust of the city god draped with corona muralis to the right, with the legend ANΘЄM – OYCIA (Münzen & Medaillen Deutschland GmbH 20, 926). The coinage of Edessa The mint of Edessa minted coins both with the image of the Roman Emperor, and the portrait of the local prince, the Edessenian ruler. Therefore you have to divide the coinage of Edessa in a 3 4 Krzyzanowska 1979c, pp. 445-57. Kaizer 2007, pp. 39-60. 4 PHILIPP SCHWINGHAMMER typological way into pieces with the image of the Roman Emperor and into pieces with the local ruler alone and together with the Roman Emperor. The first coin is a bronze coin of Caracalla (Pl. I, 11, diameter: 21.0 mm; weight: 4.33 g), which shows on the obverse the laureate, draped bust to the left and on the reverse two busts of city gods with corona muralis and veil fronted and below a baetyl (BMC, 114.8). The second one (Pl. I, 12) is a bronze coin of king Wael, described on the reverse with the aramaic legend mlk wael and showing on the reverse the baetyl. On the obverse of the third coin (Pl. II, 13) we see the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus with a Greek legend and on the reverse the local ruler Abgar VIII draped and diademed with a sceptre in his hands. The coinage of Hatra Hatra was a Mesopotamian city like the cities before, whereof much evidence is documented in ancient literature, epigraphy and locally found coins. Its rulers are known from Worod (about 110 AD) until 240 AD, when Hatra was occupied and destroyed by the Sassanid Empire under Ardashir I. These local kings are all documented in a epigraphic way, but only one, Worod, is embodied on a coin. The other coin types deal with religious emblems and local gods, especially with the trias of Shams, Syn and Bar-Maren. At this point I should mention the studies regarding Hatrenian coinage by Al-Salihi, Walker, Slocum and Udo Hartmann, with their extensive inventory of the Hatrenian coins from the collections of New York, London and Berlin. With regard to the epigraphic evidence, coin types and nominals have been mentioned in Upper Mesopotamian inscriptions from Hatra and Assur.5 For example we know a bronze weight found in Hatra (H 47) with the legend which means ‘40 As of PN (slave of god Semya) the Son of PN (God may have profit)’. This Bronze piece weights 560 g, so we can trace back a calculated As weight of about 14g . This 14 g heavy piece could be the name of the coins summarized under group 1 at the system of weight. The name As reflects indeed the Roman expression for the As copper coin and is in that point at least inspired on this side. Beside the term of the As coin you can find more economically inspired words, like ‘salary’ (H 344,7), dmīn ‘price’ (H 49,3), ’esterīn ‘stater’ (H 242, 3) und mnēn ‘mine’ (H 241, 4; 243,2; 244,2 also with its abbreviated form m H 191,2 und 192,2).6 All these terms, which have been used in general, represent in a certain way the common parlance and terms for money and commodities in this area at this time. With regard to the coin system there are the following weight standards, whereof the first is, as I mentioned before, obviously named with the Romano-Aramaic term As:7 I want to present four coin types from Hatra. The first (Pl. II, 14) shows on the obverse the radiate bust of the sun god Shams to the right, who is also mentioned in the legend as shms di hatra ‘Shamas of Hatra’; the reverse shows a frontal standing eagle sitting on an inverse SC, the common abbreviation for senatus consulto, which reflects the Hatrenian victory against the Roman Empire during the Roman occupation in 117 AD. The second one (Pl. II, 15) is largely the same type, but in a primitive way of presentation and is to be dated about 200 AD.8 5 6 7 Cf. Beyer 1998, pp. 8, 41, 106-107 and 169-81. Regarding Hatrenian inscription, see Beyer 1998. Compare the weight standards in Walker 1958, pp. 167-72; Slocum 1977, pp. 37-47; and Hartmann / Luther 2002, pp. 161-68. 8 Cf. Schwinghammer 2008, p. 18. SOME NOTES ON RELIGIOUS EMBODIMENTS IN THE COINAGE OF ROMAN SYRIA AND MESOPOTAMIA 5 The third coin (Pl. II, 16) embodies on the obverse a right standing eagle on a palm branch, also to be seen as symbol of sun god Shams, and on the reverse now the SC written in the right way. This coin was probably minted before the Hatrenian victory and the SC could be seen as part of the Roman influence in minting this coin type. The fourth coin (Pl. II, 17) represents the only coin type having the portrait of a local ruler, the king Worod, and is dated about 110 AD.9 On the obverse we can see the portrait of Worod with some kind of radiate hair style, which reminds as well of the Sassanid crown typology as the term of Sumerian hili which describes a certain wig used for religious cults and has been mentioned in the Dumuzi-Inanna texts in the third century AD.10 It could be recognized as some kind of a local corona inspired by the city god Shams with regard to the radial-looking parts of the hair. Generally speaking these few examples show us how much religious embodiments on the coins of Syria and Mesopotamia could help us to interpret the Ancient Arabian theotechny regarding its illustrations and religious intentions of designing a coin in a certain way. BIBLIOGRAPHY Abbreviations: BM British Museum, Department of Coins & Medals, London CM Bibliotheque Francaise, Cabinet des Médailles, Paris KHM Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien / Münzkabinett, Wien Literature: Baldus, H.R. (1971), Uranius Antoninus: Münzprägung und Geschichte, Antiquitas, Reihe 3, Bd. 2. Beyer, K. (1998), Die aramäischen Inschriften aus Assur Hatra und dem übrigen Obermesopotamien, Göttingen. Classical Numismatic Group 2001 Mail Bid Sale 57, Lancaster. 2001. 2004 Mail Bid Sale 67, Lancaster. 2004. 2006 Mail Bid Sale 73, Lancaster. 2006. 2008 Mail Bid Sale 79, Lancaster. 2008. Hartmann, U. / Luther, A. (2002), ‘Münzen des hatrenischen Herrschers wrwd (Worod)’. In: Schuol, M. / Hartmann, U. / Luther, A. (eds.), Grenzüberschreitungen: Formen des Kontakts zwischen Orient und Okzident im Altertum (= Oriens et Occidens 3), pp. 161–69. Hill, G.F. (1922), Catalogue of the Greek Coins of Arabia Mesopotamia and Persia (Nabataea, Arabia Provincia, S. Arabia, Mesopotamia, Babylonia, Assyria, Persia, Alexandrine Empire of the East, Persis, Elymais, Charakene). (= BMC Greek Bd. 25), London. Kaizer, T. (2002), The Religious Life of Palmyra (= Oriens et Occidens 4), Stuttgart. 9 10 Cf. Hartmann / Luther 2002, p. 161. Cf. Klein 1981. 6 PHILIPP SCHWINGHAMMER Kaizer, T. (2007), ‘Pamyre, cité grecque? A question of coinage’, Klio 89, pp. 39-60. Klein, J. (1981), Three Šulgi Hymnus, Bar-Ilan. 1981. Krzyzanowska, A. (1975), ‘Monety z piaskow Palmyry’, Biuletyn Numizmatyczny 7, pp. 121-27. Krzyzanowska, A. (1979a), ‘Mennictwo Palmyry’, Wiadomosci Numizmatyczne 23.3, pp. 143-54. Krzyzanowska, A. (1979b), ‘La monnayage de Palmyre’, in: Ninth International Congress of Numismatics, Bern, 1979, Vol. I, pp. 445-57. Krzyzanowska, A. (1979c), ‘La circulation monétaire a Palmyre d’aprés le matérial provenant de fouilles’, Wiadomosci Numizmatyczne 23.1, pp. 44-52. Krzyzanowska, A. (2002), ‘Les monnaies de Palmyre: leur chronologie et leur rôle dans la circulation monétaire de la région, Monnayages Syriens, pp. 167–73. Krzyzanowska, A. (2003), ‘Coins of Zenobia’, Wiadomosci Numizmatyczne 47, 1, pp. 73-76. Münzen & Medaillen Deutschland GmbH 2004 Auktion 14, Weil am Rhein. 2004. 2006 Auktion 20, Weil am Rhein. 2006. Schwinghammer, P. (2007), ‘Shams – Darstellungen auf Münzen und Tesserae in Nord.- und Zentralarabien’, MIN 35, pp. 8-18. Schwinghammer, P. (2008), ‘lšmš ’lh’ ţ’b[’]- Sonnengott-Darstellungen in Hatra und Südarabien im Vergleich’, MIN 36, pp. 18-21. Slocum, J.J. (1977), ‘Another look at the coins of Hatra’, ANSMN 22, pp. 37-47. SNG Cop. (Sylloge Nummorum Graecorum. The Royal Collection of Coins and Medals, Danish National Museum, Copenhagen). 1959a 35. Mørkholm, O. Syria, Seleucid Kings. 1959b 36. Mørkholm, O. Syria, Cities. Sommer, M. (2003), Hatra. Geschichte und Kultur einer Karawanenstadt im römisch parthischen Mesopotamien, Mainz. Sommer, M. (2005), Roms orientalische Steppengrenze. Palmyra – Edessa – Dura Europos – Hatra. Eine Kulturgeschichte von Pompeius bis Diocletian (= Oriens et Occidens 9), Stuttgart. Walker, J. (1958), ‘The coins of Hatra’, NC 18, pp. 167-72. Wroth, W. (1899), Catalogue of the Coins of Galatia, Cappadocia, and Syria (sic!) (= BMC Greek Bd. 21), London. SOME NOTES ON RELIGIOUS EMBODIMENTS IN THE COINAGE OF ROMAN SYRIA AND MESOPOTAMIA KEY TO PLATES Plate I 1. Classical Numismatic Group, Mail Bid Sale 73, lot 793. 2. Classical Numismatic Group, Mail Bid Sale 67, lot 1143. 3. Münzen & Medaillen Deutschland GmbH 14, lot 665. 4. Classical Numismatic Group 57, lot 847. 5. CM G54 6. BM 1908 1 – 10 – 2201 7. BM 1908 1 – 10 H 2333 8. Classical Numismatic Group 79, lot 715. 9. Münzen & Medaillen Deutschland GmbH 20, lot 926 (piece 1 of 2). 10. Münzen & Medaillen Deutschland GmbH 20, lot 926 (piece 2 of 2). 11. KHM 22786. 12. Münzen & Medaillen Deutschland GmbH 20, lot 927. Plate II 13. KHM 22846. 14. Classical Numismatic Group 79, lot 709. 15. Slocum 1977, No. 23. 16. Collection of the author. 17. BM 1963 12 – 4 – 2. 7 PLATE I 1 2 3 4 5 8 6 7 9 11 10 12 PLATE II 13 14 15 16 17