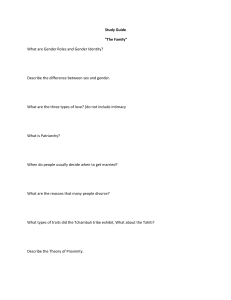

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257309424 Adaptation of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment for Elderly Filipino Patients. Article in East Asian Archives of Psychiatry · September 2013 Source: PubMed CITATIONS READS 32 71,111 7 authors, including: Jacqueline C Dominguez Jeniffer Rose Soriano St. Luke's Medical Center (Philippines) St. Luke's Medical Center (Philippines) 76 PUBLICATIONS 616 CITATIONS 4 PUBLICATIONS 49 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Cely Magpantay Ma. Lourdes Corrales Joson De La Salle University University of Santo Tomas 3 PUBLICATIONS 49 CITATIONS 11 PUBLICATIONS 115 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Frontotemporal dementia with motor neuron disease View project Burden of Disease of AD in community dwelling FIlipino ELderly View project All content following this page was uploaded by Jacqueline C Dominguez on 03 June 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. SEE PROFILE East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2013;23:80-5 Theme Paper Adaptation of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment for Elderly Filipino Patients 以菲律賓老年患者為對象的蒙特利爾認知評估量表診斷改編版 JC Dominguez, MGS Orquiza, JR Soriano, CD Magpantay, RC Esteban, ML Corrales, ER Ampil Abstract Objective: The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is an instrument that aids clinicians in detecting mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. The study aimed to adapt the MoCA for use in the Philippines, and determine its psychometric validity when used in the Filipino setting. Methods: The MoCA was adapted by a multidisciplinary team working at the Memory Center of St. Luke’s Medical Center, Manila, the Philippines. Contextual adaptation, rather than direct translation, was done. Pilot testing of the Filipino version of the MoCA (MoCA-P) was done on 12 grade 6 pupils and subsequently on 14 cognitively intact elderly people. Reliability testing of the MoCA-P was done on 25 elderly people by trained psychologists. Internal consistency, inter-rater and intra-rater reliability, as well as convergent and divergent validity of the MoCA-P were determined. Results: The MoCA-P yielded a high level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.938). Inter-rater and intra-rater reliability were 0.887 (p ≤ 0.05) and 0.969 (p ≤ 0.05), respectively. The MoCA-P correlated negatively with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (r = –0.233) and had a positive but low correlation with the Mini-Mental State Examination (r = 0.555). Conclusion: Contextual translation and pilot testing yielded several modifications of the MoCA. The MoCA-P is a reliable instrument for use in elderly Filipino patients. Further diagnostic validation of the MoCA-P to establish cutoff scores that would discriminate elderly individuals with normal cognition from those with dementia is needed to establish the clinical utility of the test. Key words: Aged; Alzheimer disease; Neuropsychological tests 摘要 目的:蒙特利爾認知評估(MoCA)量表能協助臨床醫生檢測輕度認知障礙和早期阿兹海默 病。本研究旨在把MoCA量表改編菲律賓語版本(MoCA-P),並檢視於當地醫療服務體系使用 的心理效度。 方法:由菲律賓馬尼拉聖路加醫療中心的記憶中心跨部門團隊,採用語境順應而非直接翻譯的 方法改編MoCA量表,先於12名6年級學生和14名認知功能正常的長者進行試點測試,然後由 受過訓練的心理學家向25名長者進行信度測試,以檢視量表的內部一致性、施測者間信度、施 測者內信度,以及聚合效度和分歧效度。 結果:MoCA-P量表產生高內部一致性水平(克隆巴赫系數 = 0.938)。施測者間信度和施測者 內信度分別為0.887(p ≤ 0.05)和0.969(p ≤ 0.05)。MoCA-P量表與愛普沃斯嗜睡量表呈負 相關(r = -0.233),與簡易精神狀態量表則呈正面但低相關性(r = 0.555)。 結論:MoCA-P量表因應語境順應和試點測試作幾番修改,它是診斷菲律賓老年患者的可靠工 具。為實踐研究的臨床應用,須進一步驗證MoCA-P的診斷效度,從而建立可區別認知功能正 常的長者與腦退化症患者的切點。 關鍵詞:長者、阿茲海默病、神經心理學測試 Dr Jacqueline C. Dominguez, MD, Memory Center, International Institute for Neurosciences, St. Luke’s Medical Center, Manila, Philippines. Dr Mary Grace S. Orquiza, MS, Memory Center, International Institute for Neurosciences, St. Luke’s Medical Center, Manila, Philippines. Dr Jennifer R. Soriano, MS, Memory Center, International Institute for Neurosciences, St. Luke’s Medical Center, Manila, Philippines. Dr Cely D. Magpantay, PhD, Memory Center, International Institute for Neurosciences, St. Luke’s Medical Center, Manila, Philippines. Dr Rolando C. Esteban, PhD, Research and Biotechnology Division, St. Luke’s Medical Center, Manila, Philippines. Dr Ma. Lourdes Corrales, MD, Memory Center, International Institute for 80 Neurosciences, St. Luke’s Medical Center, Manila, Philippines. Dr Encarnita R. Ampil, MD, Memory Center, International Institute for Neurosciences, St. Luke’s Medical Center, Manila, Philippines. Address for correspondence: Dr Jacqueline C. Dominguez, Memory Center, International Institute for Neurosciences, St. Luke’s Medical Center, 279 E. Rodriguez Sr. Boulevard, Quezon City, 1102 Philippines. Tel: (632) 7275558; Fax: (632) 7275559; email: jcdominguez@stluke.com.ph Submitted: 4 January 2013; Accepted: 10 June 2013 © 2013 Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists Montreal Cognitive Assessment for Elderly Filipino Patients Introduction Dementia is a progressive brain dysfunction involving memory, language, gnosis, praxis, and executive function. The cognitive impairment is sufficient to interfere with a patient’s ability to function independently.1 Dementia also causes disturbing behaviours that impair relationships with others and lead to distress to the family and the affected individual. The most common form of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease (AD),2 and age is clearly associated with an increased risk for AD.3 Since AD develops insidiously and progresses gradually, it is not uncommon that it goes unnoticed for many years before disturbing symptoms that merit medical attention occur. At the onset, when symptoms are mildest and commonly related to memory decline, such change is typically dismissed as part of normal ageing. However, early diagnosis is important as it provides an opportunity for early drug intervention, which has been shown to improve cognition4 and function, and may delay deterioration or institutionalisation in countries where elderly people are eventually cared for in nursing homes.5 Aside from early treatment, early diagnosis promotes acceptance and better understanding of the disease, its symptoms, and its course. Early diagnosis enables families to better care for their relative and plan ahead for social, financial, and legal issues that may arise from a patient’s disabilities. The cognitive domains that are affected in AD are orientation, memory, attention, executive function, language, visuospatial function, visuomotor speed, and visuoconstruction. Involvement of these domains is defined and documented through the use of neuropsychological tests that could help to identify both the impaired and preserved skills. Given that the core feature of AD is cognitive impairment, neuropsychological tests are ancillary to the diagnosis of AD. Most tests are developed in western English-speaking populations, where they have been developed from clinical experience and validated in the local population. Test performance is known to be influenced by age, education, and language as observed for the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).6 Values and beliefs can also affect neuropsychological testing.7 The issue of how culture and language affect test performance has been a topic of concern in past decades.8,9 Floor effects have been apparent when English tests were administered to non-native populations in the US, particularly because of the high cultural bias of some of the items found in the tests.10 Thus, particularly for screening instruments used in the medical field, cross-cultural adaptation is imperative. Important aspects in cross-cultural adaptation are reliability, content, and construct validity. Careful forward translation, synthesis, back-translation, expert judging, and pre-final testing components are needed.11,12 Most importantly, contextual adaptation by using experiential and conceptual equivalence to the culture where the instrument is being adapted to must be meticulously accorded.13 In an Asian country such as the Philippines, early East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2013, Vol 23, No.3 dementia or mild cognitive impairment may not be detected as some people still regard cognitive decline as part of normal ageing and elderly people are commonly spared strenuous or mentally challenging activities. Mild impairment is also not detected by the validated Filipino version of the MMSE (MMSE-P).14 There is therefore a need to adapt a good screening tool in the Philippines to help clinicians detect dementia early and accurately. This study aimed to adapt the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)15 and determine the adapted version’s psychometric reliability among the Filipino elderly. The MoCA was chosen because it has been shown to be sensitive to mild cognitive impairment15 and validated in different languages.16-19 The MoCA has also gained worldwide acceptability, being recommended as the screening instrument not only for AD, but also for other types of dementia such as vascular cognitive impairment by some professional groups and researchers.20 Methods Study Design This was a cross-sectional study conducted at the Memory Center of St. Luke’s Medical Center in Manila, the Philippines. This centre is a specialised referral unit providing assessment and treatment for patients with dementia and other related disorders. Ethics approval for the study was granted by the St. Luke’s Medical Center Institutional Ethics Review Committee. Permission to adapt the MoCA was obtained from Prof. Ziad Nasreddine, the primary author of the MoCA.15 Study Population The study participants for the pilot test were recruited from grade 6 pupils in a public elementary school and cognitively intact elderly individuals. The pre-testing participants were elderly individuals who were different from those in the pilot tests. The elderly people were recruited from the Senior Citizen Registry of Marikina, which is an outreach community of the St. Luke’s International Institute for Neurosciences. All study participants provided informed consent before any testing was done. Procedure The original version of the MoCA was translated and adapted by a multidisciplinary team comprising a neurologist, a geriatrician, 2 psychologists, a geriatric psychiatrist, an anthropologist, a speech and language therapist, and a nurse. The members were specifically chosen because of their knowledge of the concepts and objectives underlying the test items. All team members are bilingual (English and Filipino) but their mother tongue is Filipino. Since the intended users, i.e. the testers who are medical / allied medical professionals and are English-literate, the guideline for the test administrators was retained in English, and only the test instructions that would be read to the participants were translated into Filipino. To ensure the applicability 81 JC Dominguez, MGS Orquiza, JR Soriano, et al of test items to the Filipino elderly, contextual adaptation rather than simple direct translation was done, with careful consideration of the Filipino culture. The translation was compared with the original15 to verify cross-cultural equivalence. This translation was the first version of the MoCA adaptation. This version was then critiqued independently by a second multidisciplinary team with the same qualifications as the translating team. The translation was also back-translated by a nurse and physician who were not working at the memory centre and were unacquainted with the intent of the test. The critique and comments from the back-translation were discussed by all members of the 2 teams and amendments were introduced. The result was the second version of the MoCA adaptation. This version was then pilot-tested by grade 6 pupils for comprehensibility of instructions and ease of delivery. The second version was also pilot-tested by cognitively intact elderly people. The elderly participants were assessed by a neurologist to ascertain absence of dementia based on the National Institute of Non-communicative Disorders and Stroke — Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association clinical criteria.1 Observations from the pilot tests — particularly semantic, experiential, and conceptual equivalence with the original test—were incorporated in the second version. The result was the third version of the adaptation, which was referred to as the Filipino version of the MoCA (MoCA-P). All disagreements throughout the process were resolved by consensus. The guidelines to preserve equivalence in cross-cultural adaptation of health-related measures were followed.21 The cognitively intact elderly people who pretested the MoCA-P returned for re-testing after 2 weeks to assess retest reliability. The pre-testing was videotaped and the tapes were viewed and rated independently by other testers in order to assess inter-rater reliability. The pre-test participants were also administered the MMSE-P14 and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale to assess for convergent and divergent validity, respectively. The testers were psychologists with experience of MoCA test administration. Statistical Analysis Internal consistency of the MoCA-P was computed by Cronbach’s α. Test-retest reliability was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients for scores at baseline and at 2 weeks. Pearson’s correlation scores were calculated to assess the relationship between the MoCA-P and MMSE-P, and between the MoCA-P and Epworth Sleepiness Scale. All statistical analyses were done using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Windows version 17 (SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all the analyses. Results Twelve grade 6 pupils and 14 cognitively intact elderly individuals were included in the pilot test and 25 cognitively 82 intact elderly individuals were included in the pre-test. The elderly participants were community-dwelling and were representative of the diversity of Filipino communities in terms of education and ethnicity (Table). All of the elderly participants were fluent in the Filipino language. The MoCA translation was fully comprehensible to the grade 6 pilot participants. However, it was apparent from the responses of the elderly pilot participants that linguistic and cultural modifications had to be made. None among the elderly participants named the rhinoceros correctly because it seemed that the animal was not within the realm of their reality and vocabulary. Inability to name the rhinoceros by the elderly participants appeared to be a generational issue as all the grade 6 pupils in the pilot test were able to name the animal with ease. Three animals were recommended as a replacement for rhinoceros — carabao (water buffalo), crocodile, and owl. Carabao was too common, hence easy to identify, while a crocodile’s picture could be mistakenly named as lizard or alligator. The owl, which is an indigenous Philippine fauna used with medium frequency and is distinctly identifiable by its prominently big round eyes, was chosen by consensus. In the language subtest, letter fluency with ‘F’ was not possible as there are no Filipino words that begin with this letter other than the word Filipino. Thus, the letter B was chosen. It was also found that word-for-word translation of the 2 English sentences for repetition unusually lengthened the text in Filipino, and the long sentences became challenging tongue twisters. Therefore, the 2 sentences were carefully abridged while retaining their meaning and the number of words in the original version. In the abstraction subtest, the consensus was to change clock to weighing scale (‘timbangan’). This was done because the elderly pilot participants did not consider a clock to be a measuring instrument like a ruler. For these participants, a clock tells the time, but does not measure time. The elderly participants also categorised the paired items based on concrete and physical attributes. For example, a common response regarding the similarity of a bicycle and train was that both are made of metal (vs. the correct original response that both are modes of transportation). The participants also categorised items from the viewpoint of what is immediately practical, as in orange and banana are food (vs. the correct original response that both are fruits). The responses were not the best answers, but were nevertheless correct. By consensus agreement, these responses were considered acceptable and participants would not be penalised for not thinking in concepts familiar to western populations. These responses were therefore to be rated correct in the MoCA-P. Some modifications of the original test instructions were also introduced. The test sheet was folded crosswise to hide the pictures of the animals to be named because the participants were distracted by them. Another modification was made to the abstraction subtest, for which participants needed repetition to understand the instruction. Therefore, repetition of the instructions up to 2 times was allowed and East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2013, Vol 23, No.3 Montreal Cognitive Assessment for Elderly Filipino Patients Table. Demographic profile of pilot and pre-test groups.* Demographics Sex Female Male Age (years) 10-12 60-69 70-79 80-89 Education level (years) Elementary (1-6) High school (7-10) College (11-14) Postgraduate (≥ 15) Ethnicity Tagalog Bicolano Bisaya Kapampangan Ilocano * † Pilot testing of grade 6 pupils (n = 12) Pilot testing of elderly people† (n = 14) Pre-testing of elderly people† (n = 25) 5 (42%) 7 (58%) 11.5 ± 0.5 12 (100%) 6±0 12 (100%) - 7 (50%) 7 (50%) 69.6 ± 4.4 5 (36%) 9 (64%) 0 9.8 ± 3.5 4 (28%) 5 (36%) 5 (36%) 0 19 (76%) 6 (24%) 72.6 ± 7.2 10 (40%) 12 (48%) 3 (12%) 8.2 ± 3.7 9 (36%) 12 (48%) 3 (12%) 1 (4%) 12 (100%) 0 0 0 0 9 (64%) 4 (29%) 1 (7%) 0 0 9 (36%) 4 (16%) 5 (20%) 3 (12%) 4 (16%) Data are shown as No. (%) of subjects or mean ± standard deviation. All patients were cognitively intact. was incorporated in the instructions to testers. The resultant MoCA-P version finalised after the pilot testing is shown in the Figure. The MoCA-P yielded a high level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.938). Re-test reliability was done at a mean of 15.31 days (standard deviation [SD], 6.79 days) apart, although 4 of the 25 participants failed to return for re-testing. The mean MoCA scores were 16.14 and 16.81 for baseline and follow-up, respectively, with a mean change of -0.76 (SD, 2.26) points. The inter-rater and intrarater reliability were 0.887 (p ≤ 0.05) and 0.969 (p ≤ 0.05), respectively. The MoCA-P correlated negatively with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (r = –0.233) and had a positive but low correlation with the MMSE-P (r = 0.555). This low convergent validity could be due to the fact that, although both tests are measures of cognition and should be highly correlated, the MMSE-P is limited in measures of executive function, which are found in the MoCA-P. Discussion At least some degree of familiarity of participants with test items is essential for a test to be valid. In the Korean version of the MoCA, ‘velvet’ and ‘daisy’ were changed to ‘silk’ and ‘azalea’, respectively, because the original items were unfamiliar to Korean elderly people.17 In the MoCA-P, 2 words were changed in the memory list because they have no Filipino translation. Silk (‘seda’ in Filipino) was used to replace velvet because it is a familiar East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2013, Vol 23, No.3 fabric used for religious draperies and daisy was replaced by rose (‘rosas’). The elderly participants employed a different cognitive approach to western populations when determining the relationship of 2 seemingly obtuse objects as evidenced by the answers to the similarity of bicycle and train or orange and banana. Certain responses are therefore rated as correct in the MoCA-P, even if different from the original version. This issue is of particular importance in this instance when a response can only be rated as right or wrong, unlike in protocols where responses are graded in a 3-point scale from best to inappropriate answers. The same is true of the rating for the cube performance, which can only be scored as either right or wrong, whereas in other protocols such as the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale,22 the answers are rated with respect to lines, face orientation, parallelism, and dimensionality. Subjectivity was therefore observed in the testers when rating these tests, including the simple clock drawing where the tester could be lenient or strict. The need for modification of the test items and instructions in the MoCA-P supports the recommendation of the International Working Group for the Harmonization of Dementia Drug Guidelines that test instruments should be validated in the population where the tests will be used, particularly in populations for whom language and cultural experiences differ from those of the West.23 Valid assessment of elderly Filipino patients can now be done using the MoCA-P, and since the MoCA has also been validated in 83 JC Dominguez, MGS Orquiza, JR Soriano, et al Figure. Filipino version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. other Asian countries,16,17 it can be used in cross-cultural studies of dementia in Asia. This study has some limitations. Firstly, in adapting an existing instrument, conclusions based on concepts in the original instrument’s source culture may be heightened despite differences or absence of these concepts in the Filipino culture, as was evident in the abstraction subtest. Thus, an implicit limitation in this adaptation is the restriction in discovering or identifying patterns unique 84 to the Filipino elderly in exchange for content validity. Secondly, the subjectivity in rating responses justifies the development of an instruction manual to standardise test administration, rating, and interpretation. Conclusion Contextual translation and pilot testing yielded several modifications in the adaptation of the MoCA for use in the East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2013, Vol 23, No.3 Montreal Cognitive Assessment for Elderly Filipino Patients Philippines. Pre-testing study showed that the MoCA-P is a reliable instrument for use in the Filipino elderly. Due to the variability of responses that can be considered as correct by testers and subjectivity in rating responses, a manual of instructions must be developed to standardise test administration, rating, and interpretation. Further diagnostic validation of the MoCA-P to establish cutoff scores that would discriminate elderly individuals with normal cognition from those with dementia is needed to establish the clinical utility of the test. Acknowledgement This study would not have been possible without the support of the St. Luke’s Medical Center Research and Biotechnology Division, the Philippine Council for Health Related Diseases of the Philippine Department of Science and Technology, and Prof. Ziad Nasreddine who granted permission to adapt the MoCA. Declaration This study was supported by St. Luke’s Medical Center and the Philippine Council for Health and Research Development, Philippine Department of Science and Technology. The authors declared that they have no disclosures to make. References 1. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDSADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984;34:939-44. 2. Barker WW, Luis CA, Kashuba A, Luis M, Harwood DG, Loewenstein D, et al. Relative frequencies of Alzheimer disease, Lewy body, vascular and frontotemporal dementia, and hippocampal sclerosis in the State of Florida Brain Bank. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2002;16:203-12. 3. Lindsay J, Laurin D, Verreault R, Hébert R, Helliwell B, Hill GB, et al. Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective analysis from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Am J Epidemiol 2002;156:445-53. 4. Dominguez JC, Giron MS. Long term treatment of AD with donepezil in a clinical practice setting in an Asian population. Alzheimers Dement 2006;2(Suppl 1):P3-464. 5. Geldmacher DS, Provenzano G, McRae T, Mastey V, Ieni JR. Donepezil is associated with delayed nursing home placement in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:937-44. 6. Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-based East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2013, Vol 23, No.3 View publication stats 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA 1993;269:2386-91. Ardila A. Cultural values underlying psychometric cognitive testing. Neuropsychol Rev 2005;15:185-95. Manly JJ, Miller SW, Heaton RK, Byrd D, Reilly J, Velasquez RJ, et al. The effect of African-American acculturation on neuropsychological test performance in normal and HIV-positive individuals. The HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC) Group. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1998;4:291-302. Ferraz MB. Cross cultural adaptation of questionnaires: what is it and when should it be performed? J Rheumatol 1997;24:2066-8. te Nijenhuis J, van der Flier H. Immigrant–majority group differences in cognitive performance: Jensen effects, cultural effects, or both? Intelligence 2003;31:443-59. Geisinger KF. Cross-cultural normative assessment: translation and adaptation issues influencing the normative interpretation of assessment instruments. Psychol Assess 1994;6:304-12. Hambleton RK. Translating achievement tests for use in cross-national studies. Eur J Psychol Assess 1993;9:57-68. Beaton D, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:3186-91. Ligsay A. Validation of the Mini Mental State Examination in the Philippines [thesis]. Manila: University of the Philippines; 2003. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:695-9. Montreal Cognitive Assessment Hong Kong version (HK-MoCA). Available from: http://mocatest.org/pdf_files/test/MoCA-Test-HongKong_ 2010.pdf. Accessed 30 July 2009. Lee JY, Lee DW, Cho SJ, Na DL, Jeon HJ, Kim SK, et al. Brief screening for mild cognitive impairment in elderly outpatient clinic: validation of the Korean version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2008;21:104-10. Wen HB, Zhang ZX, Niu FS, Li L. The application of Montreal cognitive assessment in urban Chinese residents of Beijing [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2008;47:36-9. Rahman TT, El Gaaffary MM. Montreal Cognitive Assessment Arabic version: reliability and validity prevalence of mild cognitive impairment among elderly attending geriatric clubs in Cairo. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2009;9:54-61. Hachinski V, Iadecola C, Petersen RC, Breteler MM, Nyenhuis DL, Black SE, et al. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Canadian Stroke Network vascular cognitive impairment harmonization standards. Stroke 2006;37:2220-41. Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:1417-32. Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1984;141:1356-64. Auchus AP, Chen CP; International Working Group for the Harmonization of Dementia Drug Guidelines. Asia regional meeting of the International Working Group for the Harmonization of Dementia Drug Guidelines: meeting report. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2001;15:66-8. 85