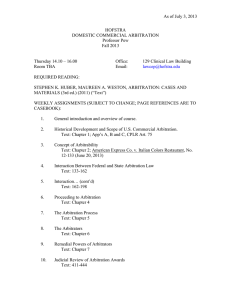

Arbitration Law in a Nutshell Chapter 1. Terms and Concepts 1. Arbitration Agreements A contract to arbitrate disputes can take one of two forms: a submission or an arbitral clause. The submission is an arbitration agreement in which the parties agree to submit an existing dispute to arbitration. The arbitral clause is a contract under which the parties agree to submit future disputes to arbitration. An agreement to arbitrate disputes must be in writing and should satisfy the standard requirements of contract formation (e.g., offer, acceptance, ‘meeting of the minds,’ consideration). The ‘emphatic federal policy favoring arbitration’ has made the requirements for entering into an arbitration agreement more flexible. A contract to arbitrate can be implied from an exchange of commercial documents. Depending on the circumstances, an email or even alleged conversations between the parties could create an agreement to arbitrate. The presumption favoring arbitration and arbitrability has made the vast majority of contracts for arbitration impervious to challenge. The arbitral clause is the more commonplace arbitration agreement. Generally, it states the obligation to arbitrate in clear and straightforward language: “Any dispute arising under this contract shall be submitted to arbitration under the rules of [a chosen arbitral institution].” Ordinarily, the arbitral clause is a provision embedded in a larger contract; despite that incorporation, legal doctrine provides that the agreement to arbitrate is a separate, self-standing contract. The separability doctrine attributes an autonomous legal character to the arbitral clause and thereby protects arbitral jurisdiction. Once a dispute arises, the parties to an arbitral clause usually enter into a submission agreement. The submission is the preliminary step in building an arbitral proceeding. It establishes the disputes that need to be resolved. In so doing, it defines the arbitrators’ jurisdiction—their right to rule. It also initiates the appointment of arbitrators. An enforceable agreement to arbitrate deprives the courts of jurisdiction to entertain matters that the agreement covers. Judicial authority to adjudicate remains in abeyance even when an arbitral award is vacated or difficulties arise in the arbitral proceeding. As a matter of law, the arbitration agreement establishes that the designated arbitrators have exclusive jurisdiction to decide submitted matters. Generally, only mutual party rescission can void an agreement to arbitrate. Court assistance is available during the proceeding when it is necessary to compel arbitration, nominate arbitrators, enforce demands for evidence, or to legitimate or give effect to the award. 2. Separability and Kompetenz-Kompetenz The separability doctrine makes the arbitral clause less vulnerable to attack; the flaws in the main 11 contract cannot impair the agreement to arbitrate, unless they also exist in the arbitration agreement. Kompetenz-kompetenz (jurisdiction to rule on jurisdictional challenges) provides that the arbitral tribunal can rule on the legitimacy of its own jurisdiction. Arbitrators have the legal right to decide whether the arbitration agreement exists, is a valid contract, and to what matters it applies. The FAA does not refer to arbitrator authority to rule on jurisdictional matters. Kompetenz-kompetenz emerged decades after the enactment of the statute. The Court incorporated the doctrine into U.S. arbitration law through its decisional law. See First Options of Chicago, Inc. v. Kaplan, 514 U.S. 938 (1995). The separability doctrine also resulted from stare 1 Arbitration Law in a Nutshell ©2021 West Academic Publishing Arbitration Law in a Nutshell Chapter 1. Terms and Concepts decisis. See Prima Paint Corp. v. Flood & Conklin Mfg. Co., 388 U.S. 395 (1967); Buckeye Check Cashing, Inc. v. Cardegna, 546 U.S. 440 (2006). The separability and kompetenz-kompetenz doctrines reinforce the independence of the arbitral process. Court supervision of the arbitrator’s determination of jurisdictional issues is likely to be highly tolerant. The law requires these determinations to be subject to deferential judicial review. Moreover, as in most hospitable jurisdictions to arbitration, judicial scrutiny of arbitrator determinations on jurisdiction is delayed until the rendition of the final award. The final award combines the ruling on the merits with any jurisdictional determinations. The joinder of the two types of rulings was intended to reduce the likelihood of a judicial reversal of either determination. See First Options of Chicago, Inc. v. Kaplan, 514 U.S. 938 (1995). For all intents and purposes, then, the arbitral tribunal conclusively decides any question pertaining to the validity and scope of its own adjudicatory authority. Unlike court decisions on jurisdiction, arbitrator awards on jurisdiction are not subject to de novo review. 3. Arbitrability Arbitrability establishes which disputes can be submitted to arbitration as a matter of law. Inarbitrability can prevent the enforcement of an arbitration agreement or an arbitral award. Inarbitrability thereby limits the parties’ right to engage in arbitration and the designated arbitrators’ right to rule. Inarbitrability can arise as a result of the subject matter of the dispute or because of contractual flaws in the arbitration agreement. Under subject-matter inarbitrability, a dispute on matters directly linked to the public interest cannot be submitted to arbitration. Matters of criminal culpability, for example, are deemed inarbitrable because courts have exclusive jurisdiction over Bill-of-Rights litigation. Therefore, unless plea-bargaining is considered a form of arbitration (a dubious proposition at best), allegations of bribery, criminal violations of RICO, or fraud in matters of tax liability are inarbitrable because these disputes involve the public interest—even though the alleged misconduct may result from private commercial conduct. To some extent, subject-matter inarbitrability overlaps with the public policy exception to the enforcement of arbitral agreements and awards. In each, public interest considerations prevent the recourse to arbitration or extinguish the outcome it reaches. More difficult problems of subject-matter inarbitrability arise when disputes involve the government regulation of commercial activity through, for example, antitrust or securities statutes. The difficulty can become acute in domestic litigation or in the context of international business transactions. Statutory claims raise matters pertaining to the authority of the government to implement regulatory policy, the individual parties’ freedom of contract, whether the transactions are ‘one-off’ (single-time) transactions or have a larger presence in the marketplace, and whether arbitrators have sufficient integrity—as well as the necessary jurisdiction, independence, distance, and competence—to rule on matters of regulatory law. The U.S. Supreme Court has expressly rejected the traditional view that statutory disputes are inarbitrable. See Mitsubishi Motors Corp. v. Soler Chrysler-Plymouth, Inc., 473 U.S. 614, 632 (1985) (“The mere appearance of an antitrust dispute does not alone warrant invalidation of the selected forum on the undemonstrated assumption that the arbitration clause is tainted.”). The federal judicial position is that regulatory claims, regardless of whether they arise under international or domestic contracts, can be submitted to arbitration. See Gilmer v. 2 Arbitration Law in a Nutshell ©2021 West Academic Publishing Arbitration Law in a Nutshell Chapter 1. Terms and Concepts Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U.S. 20 (1991) (“. . . the ADEA is designed not only to address individual grievances, but also to further important social policies. . . . We do not perceive any inherent 14 inconsistency between these policies, however, and enforcing agreements to arbitrate age discrimination claims. . . . The Sherman Act, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, RICO, and the Securities Act of 1933 all are designed to advance important public policies, but . . . claims under those statutes are appropriate for arbitration.”). Inarbitrability also functions on the basis of contract. In these circumstances, the challenges to arbitrability converge on the contract of arbitration—its existence, making, and scope. The allegation of inarbitrability can be based upon the lack of an agreement to arbitrate, a contract deficiency in an agreement that does in fact exist, or the limited scope of an otherwise existing and valid arbitration contract. Under some laws, a failure to follow the provisions of the arbitration agreement in organizing the arbitration can lead to inarbitrability. Contract directives are the gateway to arbitration. See First Options of Chicago, Inc. v. Kaplan, 514 U.S. 938 (1995). Without an actual, enforceable, and applicable agreement, there is no legal obligation to arbitrate. A few case law rules have a direct bearing upon the inarbitrability defense. First, courts generally interpret a broadly-worded arbitration agreement as referring to all transactional disputes that arise between the parties. Therefore, a broad reference to arbitration (“any dispute arising under this contract”) encompasses—as a matter of law—contract problems relating to performance, delivery, conformity to specifications, excuse, and the defenses to performance, as well as statutory claims pertaining to the public regulation of commercial conduct (bankruptcy, antitrust, securities, and possibly taxation). A broad reference to arbitration also encompasses civil rights claims. Penn Plaza v. Pyett, 556 U.S. 247 (2009), however, indicates that specific mention must be made of discrimination claims in the arbitration agreement. In some circumstances, the reference to arbitration may include jurisdictional questions relating to the scope of the contract— if the parties include an addendum to that effect in the arbitration agreement (a so-called Kaplan jurisdictional delegation clause) that attributes authority to the arbitrators to interpret the arbitral clause itself. It may, therefore, be necessary to exclude expressly matters that the parties do not wish to submit to arbitration. Second, state contract law generally governs the validity and construction of an arbitration agreement. Therefore, questions pertaining to the formation of the contract and its validity— adhesion, unconscionability, and other restrictions that protect consumer rights—are resolved pursuant to the applicable state law. Because the U.S. law on arbitration has been federalized, any state contract law provision that disables arbitration agreements is subject to challenge under the preemption doctrine. To survive preemption, the statutory disability must apply to contracts in general; it cannot be directed at arbitration agreements alone. Rulings that adhesive arbitration agreements are unconscionable have been especially common in employment and consumer cases in the state and federal courts in California. See, e.g., Chalk v. T-Mobile USA Inc., 560 F.3d 1087 (9th Cir. 2009). The Court’s recent ruling in AT & T Mobility v. Concepcion, 563 U.S. 333 (2011), however, voided an entire line of California decisional law (the Discover Bank case et. al.) in which the state courts invalidated arbitration agreements because they contained class action waivers and, therefore, arguably compromised the legal rights of the weaker party to an adhesive agreement. The Court held that, no matter how justifiable a state public policy might be, the 3 Arbitration Law in a Nutshell ©2021 West Academic Publishing Arbitration Law in a Nutshell Chapter 1. Terms and Concepts California decisional law conflicted with the “fundamental objectives” of FAA § 2 and was preempted by federal law. As a general rule, courts uphold arbitration agreements no matter their would-be deficiencies. Third, the U.S. Supreme Court has proclaimed that arbitral proceedings are a viable form of adjudication. According to the Court, arbitration is as effective as court proceedings for the protection of legal rights. Legal rights, therefore, are neither diminished nor destroyed by the submission to arbitration. Moreover, each arbitration stands on its own and has no significance beyond the private agreement and relationship that gave rise to it. Each arbitration is a stand-alone and self-contained event. Finally, the unstated view in many of the U.S. Supreme Court’s rulings is that arbitration is, as a matter of law, in the parties’ and society’s best interest. Some access to justice is better than none at all. This position limits considerably contract inarbitrability. As long as the parties refer to arbitration, they intend to arbitrate all disputes no matter what contract flaws may exist. The presumption that arbitration is in the best interest of all the affected parties can remedy flaws that might otherwise render the agreement unenforceable. 4. The Arbitral Process Arbitration, however, is not a remedial panacea. In some—but certainly not all—instances, arbitration provides a better, or even the best, dispute resolution protocol. It is one of several adjudicatory possibilities available to parties. It should be chosen intelligently—i.e., only if it effectively responds to the parties’ actual needs and promotes their goals. Like judicial litigation, mediation, or party negotiations, arbitration has advantages and disadvantages. The use of the remedy should be based on a calculation of gains and losses it brings with a view of achieving maximum benefits for the parties. In every case, choosing between judicial litigation, arbitration, or structured negotiation requires a clear understanding of the circumstances of the dispute and the operation and characteristics of the available remedies. Court proceedings are generally protracted and costly; appeal is available and discovery can be complex, yet inconclusive. The courts are seen as guarantors of fairness and impartiality. Due process in judicial litigation, however, is often more theoretical than real. Many judicial trials end in a settlement that results from the parties’ need to manage their risk of loss. While arbitral adjudication is not infallible, it provides sensible and effective justice. When an arbitral proceeding results in a settlement, it is memorialized in an ‘award on agreed terms’. The latter is enforceable as an award; it is not merely a contract. An award on agreed terms is final and binding and can be coercively enforced by a court pursuant to the ‘emphatic federal policy favoring arbitration’. To resolve intractable problems with a settlement, the parties must return to court. Arbitral proceedings usually take place in accordance with the rules of an administering arbitral institution, like the American Arbitration Association (AAA) or the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). The institutional rules organize the arbitral process into various stages: (1) the constitution of the arbitral tribunal; (2) the establishment of the tribunal’s jurisdiction through the terms of reference; (3) the selection of a procedural format for the hearings; (4) the trial phase of the process; (5) the deliberations; and, finally, (6) the rendering of an award. Parties can also customize their arbitration. Judicialization is always possible, but, ordinarily, the contracting parties trust the arbitrators and the arbitral process to provide a fair result. 4 Arbitration Law in a Nutshell ©2021 West Academic Publishing Arbitration Law in a Nutshell Chapter 1. Terms and Concepts Following receipt of a ‘demand for arbitration’ from the aggrieved party, the arbitral administrator notifies the other party of the demand, delivers it, and requests that it file an answer. The parties nominate arbitrators pursuant to their agreement or, in the event of an impasse, the arbitral administrator or a court of law (in exceptional circumstances) names the arbitrators. The arbitral administrator can assist the parties by providing arbitrator lists. Legal counsel can also assist clients to choose arbitrators. The party-designated arbitrators name a neutral presiding arbitrator. Despite their connection to one of the parties, party-appointed arbitrators are expected to act in a generally disinterested manner. How sufficient or workable arbitrator impartiality can be achieved is difficult to define. Some courts believe that the presence of a neutral arbitrator is sufficient to guarantee the impartiality of the adjudicatory proceeding and result. Moreover, they add, the arbitrating parties are entitled to ‘their’ arbitrator on the tribunal so that they can have confidence that their positions are heard and considered, especially during tribunal deliberations. Arbitral administrators, however, believe that all arbitrators—even those who are party-appointed—should be as neutral as the presiding arbitrator. The disclosure of potential conflicts of interest by both prospective and sitting arbitrators furthers arbitrator transparency. Arbitrators may also develop conflicts during the proceedings. Arbitral administrators can appoint emergency or interim arbitrators to address matters involving the preservation of assets and evidence prior to the constitution of the actual arbitral tribunal. The failure of the arbitrators to disclose relevant information can result in the vacatur of the award on the basis of partiality. Depending upon the specific circumstances, arbitrators can refuse to serve on the arbitral panel or disqualify (recuse) themselves because of an existing or potential conflict of interest or for personal reasons. The parties can also file a motion to disqualify an arbitrator before the arbitral tribunal, the administering arbitral institution, or a court of law. Such filings should remain within the arbitral process whenever possible. With the ‘acquiescence’ of the parties and under the ‘direction’ of the arbitral administrator, the arbitral tribunal chooses a venue for holding the arbitration and sets a time for the initial hearing. At this stage of the process, parties submit a deposit for arbitrator and administrative fees with the arbitral administrator. An arbitration can be conducted solely on the basis of submitted documents. In an ‘arbitration on the documents’, the parties supply the arbitral administrator with a statement of their positions and allegations, as well as the evidence in support of their claims. The arbitral tribunal or the sole arbitrator then rules on the dispute on the basis of the submissions. Hearings are not held. Arbitral trials can range from rulings on a written record to an abbreviated hearing process to protracted proceedings that include pretrial discovery, testimonial evidence, and crossexamination. How arbitral hearings are conducted can be determined in the arbitration agreement or result from the parties’ ability to reach a mutual agreement once a dispute arises. In the event of disagreement, the arbitral tribunal—‘assisted’ by the arbitral administrator—establishes the logistical protocol for the arbitral trial. Once these preliminary matters are resolved, the hearings begin. The parties’ expectation is to participate in a flexible and fair hearing process. The arbitrators generally establish and supervise the arbitral procedure. They have sufficient authority to thwart trial tactics that 5 Arbitration Law in a Nutshell ©2021 West Academic Publishing Arbitration Law in a Nutshell Chapter 1. Terms and Concepts unnecessarily lengthen the proceedings. As a rule, the parties want a sufficient opportunity to make their case. Then, they want a final and binding ruling from the arbitral tribunal. Arbitration usually does not include a right to pretrial discovery or to appeal on the merits. The parties can engage in cooperative record-building by exchanging documents and witness lists prior to the commencement of the hearing. The arbitral tribunal decides whether proffered evidence is relevant and evaluates the significance of the admitted evidence. While the arbitrating parties have the right to be heard, neither side can abuse their rights by manufacturing specious arguments, issues, and requests for evidence—thereby tactically prolonging the proceeding for litigious advantage. Arbitrators are generally intolerant of such conduct. When the record is established, the parties present their closing arguments and final briefs. The arbitral tribunal then closes the hearing and adjourns to deliberate. The tribunal’s deliberations are private; only the arbitrators are present. As noted earlier, the expectation is that partydesignated arbitrators will highlight the various points in their appointing party’s case. It is important to arbitrating parties to have a sense that their position is being considered at this stage of the process. A decision can be, and usually is, reached by simple majority vote. Especially in domestic arbitral practice, tribunals are unlikely to provide reasons with rendered awards; reasons are meant to explain how the arbitrators reached their determination. Awards usually follow a standard format: A statement of the facts, a description of the issues, the parties’ respective positions, and a disposition of the matters submitted. The practice of not providing an opinion with domestic awards is intended to discourage the possibility of a judicial review of the merits, especially of the arbitrators’ application of law. The practice, however, is no longer as pervasive as it once was. Arbitrators are more confident that courts will defer to them and limit their scrutiny to how the arbitrators conducted the proceedings. They also realize that an explanation can create greater party acceptance of the result and the process that gave rise to it. Arbitration statutes should consider integrating ‘privileged reasons’ into their regulation of arbitral awards. The practice arose in English maritime arbitration and involves the arbitral tribunal’s communication of its assessments of the case to each party—‘off the record’. The practice wards off judicial merits reviews while explaining the reasons for the results to the parties. 5. The Case Groupings Four sets of case trilogies represent the pillars of U.S. arbitration law. The first, the Steelworkers Trilogy, announced in 1960, established that arbitration had a fundamental role to play in the resolution of labor and management disputes in the unionized workplace. See United Steelworkers of Am. 23v. American Mfg. Co., 363 U.S. 564 (1960); United Steelworkers of Am. v. Warrior & Gulf Navigation Co., 363 U.S. 574 (1960); and United Steelworkers of Am. v. Enterprise Wheel & Car Corp., 363 U.S. 593 (1960). The labor arbitration cases articulated the basic legal principles that would come to govern most of the other forms of arbitration. The doctrines developed in labor arbitration eventually were incorporated into the FAA. In Granite Rock Co. v. Int’l Bro. of Teamsters, 561 U.S. 287 (2010), the Court recognized, in fact, that a set of unitary legal principles regulated arbitration no matter the area in which it was applied and the disputes it addressed. 6 Arbitration Law in a Nutshell ©2021 West Academic Publishing Arbitration Law in a Nutshell Chapter 1. Terms and Concepts The second trilogy, the ‘Federalism’ Trilogy, came a number of years after The Steelworkers Trilogy. It made clear that the FAA was the controlling statute in matters of arbitration. Conflicting state law provisions could not undo the FAA’s jurisdictional hold over arbitration. See Moses H. Cone Mem. Hosp. v. Mercury Constr. Co., 460 U.S. 1 (1983); Southland Corp. v. Keating, 465 U.S. 1 (1984); Dean Witter Reynolds v. Byrd, 470 U.S. 213 (1985). The FAA, especially Sections Two and Ten which respectively legitimated arbitration agreements and awards, applied to all transactions that had an arguable connection to interstate commerce. The Commerce Clause and the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution combined to guarantee the federal power over arbitration. The command of the FAA reached federal courts sitting in state law cases, state legislation that might directly or incidentally affect arbitration, and state court rulings in ordinary contract cases. In effect, the federalization of U.S. arbitration law led to the creation of a federal right to arbitrate that had a clear but ill-defined constitutional standing. The first Federalism Trilogy was eventually affirmed by a second group of cases on federalization. They eliminated any doubts about federalization that may have been created by Volt Information Sciences v. Stanford University, 489 U.S. 468 (1989). See Allied-Bruce Terminix Cos., Inc. v. Dobson, 513 U.S. 265 (1995); Doctor’s Associates, Inc. v. Casarotto, 517 U.S. 681 (1996); Buckeye Check Cashing, Inc. v. Cardegna, 546 U.S. 440 (2006); Preston v. Ferrer, 552 U.S. 346 (2008); AT & T Mobility v. Concepcion, 563 U.S. 333 (2011). In the Court’s assessment, a single, uniform framework of substantive legal rules was vital to the status and operation of arbitration. Uniformity created effective legal regulation. A multiplicity of views, disagreement, and the exercise of discretion would render the necessary unity of approach impossible to achieve. The federal right to arbitrate eclipsed the political authority of states and the independent jurisdiction of state courts. In effect, the FAA represented a statement of national policy on arbitration. Acquiescing to states’ rights in this area would have brought about a nationwide denial of due process. Tolerating exceptions—large or small—would have robbed arbitration of its universal reach. See, e.g., Buckeye Check Cashing, Inc. v. Cardegna, 546 U.S. 440 (2006). A third trilogy of cases addressed the authority of arbitrators to resolve issues that arose at the head of the arbitral process, including their ability to decide 25 challenges to their own jurisdictional authority. The case law created two regimes: first, a contractual framework in which the parties could agree (“clearly and unmistakably”) to confer authority on the arbitrators to decide jurisdictional challenges. Then, a common law framework under which arbitrators acquired the right to decide matters of procedural arbitrability arising from the parties’ conduct (e.g., a waiver of the right to arbitrate arising from participation in a judicial action), as well as the power to construe the content of the arbitral clause itself. See First Options of Chicago, Inc., v. Kaplan, 514 U.S. 938 (1995); Howsam v. Dean Witter Reynolds, Inc., 573 U.S. 79 (2002); Green Tree Fin. Corp. v. Bazzle, 539 U.S. 444 (2003). The enhanced threshold authority of the arbitrator was, to some extent, destabilized by the holding in Stolt-Nielsen v. AnimalFeeds Int’l, 559 U.S. 662 (2010), in which the Court ruled that, in construing an arbitral clause, arbitrators could not reach conclusions that imposed the arbitrators’ personal views of the bargain and public policy upon the arbitrating parties. The arbitrators’ interpretation of the arbitral clause could not incorporate ‘alien’ content into the arbitration agreement. See Rent-A-Center v. Jackson, 561 U.S. 63 (2010). The Court placed other limitations on the arbitrators’ authority to exercise their jurisdictional and interpretive authority. In Rent-A-Center v. Jackson, the Court held that the arbitrators’ right to rule 7 Arbitration Law in a Nutshell ©2021 West Academic Publishing Arbitration Law in a Nutshell Chapter 1. Terms and Concepts on jurisdiction must be validated by a court of law. Finally, in BG Group PLC v. Republic of Argentina, 572 U.S. 25 (2014), the Court attributed enormous decisional authority to arbitrators by holding that, in reviewing an award pertaining to a World Bank (or ICSID) arbitration, arbitrators could alter the provisions of an international treaty in deciding the parties’ dispute. Lastly, a fourth trilogy consisted of a group of cases on international litigation. See The Bremen v. Zapata Off-Shore Co., 407 U.S. 1 (1972); Scherk v. Alberto-Culver Co., 417 U.S. 506, reh’g denied, 419 U.S. 885 (1974); Mitsubishi Motors Corp. v. Soler Chrysler-Plymouth, Inc., 473 U.S. 614 (1985). The need to have recourse to arbitration is even more pressing in international commerce. Without a viable system of international arbitration, transborder commerce could not take place. International merchants and transactions would be overwhelmed by risk if there were no process for imposing contract accountability. The judicial enforcement of arbitral agreements and awards across national boundaries was a vital source of stability for international commercial transactions. Some of the international decisions played a decisive role in crafting the general domestic doctrine on arbitration. They gave rise to another string of cases on subject-matter or statutory arbitrability. For example, the ruling in Mitsubishi, part of the international litigation trilogy, gave rise to the holdings in Shearson/Am. Express, Inc. v. McMahon, 482 U.S. 220 (1987), and Rodriguez de Quijas v. Shearson/Am. Express, Inc., 490 U.S. 477 (1989). These two cases eventually led to the creation of the securities arbitration industry. Gilmer v. Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U.S. 20 (1991), integrated the principles of the Steelworkers Trilogy into the nonunionized workplace, thereby posing a substantial challenge to the rule of Alexander v. Gardner-Denver, 415 U.S. 36 (1974), as well as generating the field of employment arbitration. In fact, in 14 Penn Plaza v. Pyett, 556 U.S. 247 (2009), the Court integrated the Gilmer arbitrability rule into CBA arbitration and reduced the status of Gardner-Denver to a “narrow holding,” the application of which it described as limited. 8 Arbitration Law in a Nutshell ©2021 West Academic Publishing