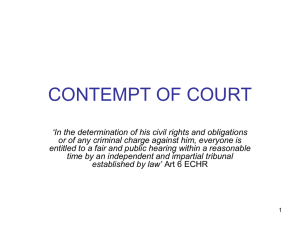

3.0 LAWYER IN CONTEMPT: IS THE SITUATION GETTING WORSE? 3.1 The Position in Malaysia Article 126 of the Federal Constitution grants the Federal Court, Court of Appeal, and High Court the authority to punish contempt. The power to punish contempt mentioned also provided again under Section 13 of Courts Judicature Act 1964. Additionally, Section 99A of the Subordinate Courts Act grants subordinate courts the power to punish contempt, with reference to Section 9 of the third schedule. However, this constitutional provision lacks specific details regarding the definition of contempt offenses, procedural requirements, defences available, and appropriate sentencing guidelines. Consequently, the absence of a codified Contempt of Court Act has created ambiguity in its application and raised concerns about the consistency and fairness of the judicial process. By comparing Malaysia's legal framework with countries such as India and England, where specific acts govern contempt of court, it becomes evident that Malaysia's reliance on common law principles and constitutional provisions hampers the establishment of a comprehensive and uniform system for dealing with contempt. The lack of a codified act has impeded the clarity, certainty, and predictability of contempt proceedings in Malaysia, necessitating immediate attention. Acknowledging the need for comprehensive legislation, the Bar Council of Malaysia has proposed a Contempt of Court Act aimed at addressing the existing gaps and providing clear guidelines for contempt-related matters. This proposed act, presently under consideration by the Attorney General's chambers, aims to enhance the legal framework governing contempt of court and streamline the process to ensure consistent and fair outcomes. In the absence of specific legislation, the Rules of Court 2012 serve as a partial guide for contempt proceedings in Malaysia. These rules provide procedural guidelines encompassing the filing of applications, service of documents, and the rights of individuals accused of contempt. Upholding principles of natural justice, the accused individuals are guaranteed a fair hearing, the opportunity to present their case, and the right to legal representation. 3.1.1 Punishment for Contempt of The Court The courts in Malaysia possess wide discretionary powers in sentencing for contempt, as opposed to statutory offences with defined punishment or sentencing. While there are no specific limits on punishment, Order 52 r. 9 of the Rules of Court 2012 provides for fines and imprisonment. The absence of clear guidelines on sentencing limits raises concerns about consistency and leaves the discretion to the courts, potentially resulting in varying penalties for similar contemptuous behavior. In addition, the lack of clear guidance regarding sentencing limits raises concerns about the potential for arbitrary or excessive punishments. 3.2 Enforcement Challenges 3.2.1 Balancing Judicial Process and Freedom of Expression Enforcing contempt of court laws requires striking a delicate balance between safeguarding the judicial process and upholding the right to freedom of expression enshrined in Article 10 of the Federal Constitution. Determining the threshold at which expression becomes contemptuous can be complex, necessitating careful consideration of competing interests. 3.2.2 Burden of Proof Proving that an act of contempt has interfered with the administration of justice presents inherent difficulties. The burden of demonstrating the impact of contemptuous behavior on the judicial process falls upon the prosecution, requiring robust evidence and legal arguments. 3.2.3 Self-Censorship and Chilling Effect The absence of clear guidelines and the discretionary nature of contempt proceedings may engender a climate of self-censorship, where individuals refrain from expressing opinions for fear of potential punishment. The chilling effect of self-censorship poses a challenge to the open exchange of ideas and public discourse.