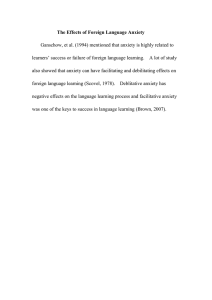

J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25:503–517 DOI 10.1007/s10826-015-0225-4 ORIGINAL PAPER Effectiveness of an Individualized Case Formulation-Based CBT for Non-responding Youths with Anxiety Disorders Irene Lundkvist-Houndoumadi1 • Mikael Thastum1 • Esben Hougaard1 Published online: 3 June 2015 Springer Science+Business Media New York 2015 Abstract The study examined the effectiveness of an individualized case formulation-based cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for youths (9–17 years) with anxiety disorders and their parents after unsuccessful treatment with a manualized group CBT program (the Cool Kids). Out of 106 participant youths assessed at a 3-month follow-up after manualized CBT, 24 were classified as non-responders on the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale (CGI-I), and 14 of 16 non-responders with anxiety as their primary complaint accepted an offer for additional individual family CBT. The treatment was short-term (M sessions = 11.14) and based on a revised case formulation that was presented to and agreed upon by the families. At post-treatment, nine youths (64.3 %) were classified as responders on the CGI-I and six (42.9 %) were free of all anxiety diagnoses, while at the 3-month follow-up 11 (78.6 %) had responded to treatment and nine (64.3 %) had remitted from all anxiety diagnoses. Large effect sizes from pre- to post-individualized treatment were found on youths’ anxiety symptoms, self-reported (d = 1.05) as well as mother-reported (d = .81). There was further progress at the 3-month follow-up, while treatment gains remained stable from post-treatment to the 1-year follow-up. Results indicate that non-responders to manualized group CBT for youth anxiety disorders can be helped by additional CBT targeting each family’s specific needs. Keywords Non-responders Anxiety disorders CBT Case formulation Individualized treatment & Irene Lundkvist-Houndoumadi irenelh@psy.au.dk 1 Department of Psychology and Behavioural Sciences, Aarhus University, Bartholins Allé 9, 8000 Aarhus C, Denmark Introduction Anxiety disorders are amongst the most common psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents (Costello et al. 2011). They negatively influence the developmental trajectories impacting family processes, youths’ functioning with peers, school, and recreation (Essau et al. 2000). Furthermore, longitudinal research has found above-average levels of life interference into early adulthood (Last et al. 1997) and anxiety disorders are considered gateway disorders, predicting mental health problems in adulthood, such as anxiety and depression (Kessler et al. 2009; Merikangas et al. 2010). During the past two decades, cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents (from now on referred to as youths) has been evaluated in an increasing number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), as evidenced by 41 studies included in a recent Cochrane review (James et al. 2013), compared to only 18 studies included in an earlier review (James et al. 2005). The studies in James et al. (2013) meta-analysis examined the effectiveness of manualized CBT that varied in duration (9–20 sessions), degree of parental participation and was either individual or group. Findings indicated that CBT is an effective treatment for anxiety disorders in youths, with the mean remission rate for any anxiety disorder diagnosis being 59.4 %, while no difference was found in the outcome of the different formats of CBT. Another meta-analysis by Reynolds et al. (2012) reported a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = .77) for youth-reported anxiety symptoms after CBT. Group CBT had a medium effect size, while individual CBT had a large effect size and disorder-specific CBT had a larger effect size than generic CBT. However, the only disorder that was examined both specifically and generically was social phobia and there 123 504 was therefore a confounding between the specificity of treatment and the anxiety disorder treated. In contrast to Reynolds et al. (2012), Liber et al. (2008) found no difference in the efficacy of individual CBT compared to group CBT, while a recent effectiveness study by Wergeland et al. (2014) also did not find any significant differences between those two formats. CBT’s effectiveness notwithstanding, about 40 % of youths do not remit (James et al. 2013). A recent systematic literature review (Lundkvist-Houndoumadi et al. 2014) found some evidence for pre-treatment symptomatic severity and non-anxiety comorbidity in youths predicting a worse end-state functioning, but not a lower degree of improvement. Few of the included studies examined the primary diagnosis as a predictor, but two of those that did, found some evidence for social phobia (SoP) being associated with a worse treatment outcome (Crawley et al. 2008; Kerns et al. 2013). This finding was also supported by two recent extensive studies (Compton et al. 2014; Hudson et al. 2015). Lundkvist-Houndoumadi et al. (2014) also reported finding some support that parental psychopathology, primarily anxiety and depression, was associated with worse outcomes of CBT for youth, when parental psychopathology was assessed through self-reports. However, two studies that assessed parental psychopathology through diagnostic interviews, reported results that were partially in opposite direction to each other (see Legerstee et al. 2008; Bodden et al. 2008). Thus, no predictor of treatment outcome has been consistently supported in the literature, a conclusion similar to the one drawn by Taylor et al. (2012) regarding the adult literature. They point out the need to develop strategies in order to improve treatment outcomes if the initial treatment has not contributed to clinical improvement, one of their suggestions being to re-evaluate the case-formulations in case of non-response. Non-response has been defined variously across studies, but in broad terms non-responders are participants, who might have experienced some symptom reduction, but have not shown clinically significant improvement, or their target symptoms are still clinically significant after the end of treatment (Taylor et al. 2012). Few have examined whether youths with anxiety disorders, who have not responded to a standard manualized CBT program, can progress through additional therapy. Perini et al. (2013) highlighted the need for developing a stepped-care approach to treating anxious children. Legerstee et al. (2010) offered 91 youths (aged 8–16) a standardized stepped care CBT. As a first treatment step youths were offered group or individual CBT following the Friends Program (Barrett et al. 2000), consisting of ten child sessions and four separate parent sessions. Treatment response was defined as youths being free of all anxiety diagnoses. Thirty-nine youths (43 %) responded to the first 123 J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25:503–517 treatment step, while after the second treatment phase, which consisted of ten standardized individual CBT sessions involving both the child and the parents, out of the 50 youths receiving the additional treatment, 37 (74 %) were free of their anxiety disorders. Similarly, van der Leeden et al. (2011) offered 132 youths manualized (group or individual) CBT, which consisted of the Friends Program (Barrett and Turner 2000). When assessments at posttreatment indicated the presence of an anxiety disorder and/ or self-reported anxiety levels above the clinical cut-off point, a second and possibly a third treatment phase were offered. Each of the additional treatment phases consisted of 5 additional sessions of manualized CBT and parents were also included in each session. They found that after the first phase, 60 youths (45 %) had remitted from all anxiety diagnoses, and of the 24 youths that received the two additional phases (i.e., 10 extra sessions), 14 youths (58 %) remitted from all diagnoses. CBT is commonly implemented through manuals, which have been suggested to enable evidence-based practice, securing therapist adherence and facilitating dissemination (Kendall et al. 2008). However, manualized treatments have also received criticism, as they are limited in their applicability to the broad range of problems encountered in clinical practice (Carroll and Rounsaville 2008). As Southam-Gerow et al. (2012) point out, the treatment programs consider specific child disorders, without considering the multiple factors (i.e., child and family factors, therapist factors, organization factors, and service system factors), which all influence how potent a treatment will be. In order to be able to individualize therapy and guide clinicians’ decision making during treatment, Weisz et al. (2013) proposed creating flowcharts through weekly feedback systems, based on assessments of each youth’s treatment response. The weekly feedback system was tested together with a modular treatment protocol for anxiety, depression, and conduct problems and showed good results (see Weisz et al. 2012). This suggests that a more personalized approach may be powerful. In accordance to Taylor et al.’s (2012) suggestion, Persons (1991) advocated a case formulation model, in order to tailor treatment to the needs of the individual client. Treatment plans are made, by integrating in the evidence-based treatment procedures, elements the clinician finds suitable, depending on the factors that contribute to the maintenance or protection of the youth’s psychological problems. Arguably, this approach can easily be implemented in clinical practice. We would suggest that among youths who have not responded to CBT, it would prove to be especially helpful, since it may guide clinicians in planning the subsequent treatment step, after integrating their knowledge on the family obtained during the first step of treatment. Furthermore, it encourages a collaborative J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25:503–517 stance, as the families are presented with the case formulation and invited to comment upon it, which is in accordance to participatory decision-making that according to Chorpita and Daleiden (2014) is prioritized in the paradigm of individualized care within service systems. The present study can be considered to be an evaluation of a second step of treatment, offered non-responders after a manualized group CBT intervention, following the Cool Kids Program (Rapee et al. 2000) that was recently evaluated in a RCT (Arendt et al. 2015). In the RCT 109 youths (aged 7–16) with a primary anxiety disorder received treatment and results showed that at post-treatment 27 youths (48 %) were free of all anxiety diagnoses, while at the 3-month follow-up 55 (58 %) were. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of an individualized, case formulation-based CBT for youths with anxiety disorders and their parents, after unsuccessful group treatment with manualized CBT. We hypothesized that a case formulation-based individualized CBT would contribute to a significant decrease in anxiety symptoms and in perceived life-interference due to the anxiety. Method Participants Participant youths were recruited from the Anxiety Clinic for Children and Adolescents at Aarhus University in Denmark, from January 2011 to April 2012 in connection with an RCT (Arendt et al. 2015) on a manualized CBT for youths with anxiety disorders and their parents (the Cool Kids Program; Rapee et al. 2000). In addition to the 109 participants from the RCT, 10 more youths treated in two non-randomized groups were included, while 13 were excluded, because they were lost to evaluation at the 3-month follow-up, when responder status was assessed. Based on the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement scale (CGI-I; Guy 1976), 24 youths (22.6 %) were classified as non-responders. Eight youths were excluded, since two had been admitted to treatment elsewhere and six appeared to have had another primary difficulty than anxiety (eating disorder: 2, autism spectrum disorder: 3, severe cognitive difficulties: 1). Of the 16 youths offered additional treatment, two declined (one family had moved to another part of the country and the other one did not believe further treatment was needed), resulting in our final sample of 14 participant non-responders. The youths (eight girls and six boys) were of Danish ethnic background and had a mean age of 12.7 years (SD = 3.1). Almost all youths were living with both parents (n = 12, 86 %). The highest completed education of parents was most commonly further/higher education (mothers n = 10, 71.4 %; 505 fathers n = 8, 61.54 %), while few had a vocational education (mothers n = 2, 14.3 %; fathers n = 3, 23 %) or a high-school equivalent (mothers n = 2, 14.3 %; fathers n = 2, 15.4 %). Age, gender, diagnosis and CGI-scores of participants appear in Table 1. At referral one of the youths (ID: 8) received medication for her ADHD symptomatology and another (ID: 6) for his depressive symptoms. Three of the non-responding youths (ID 2, 10, 12) were responders after the manualized treatment, but relapsed in the 3-month follow-up period, while three (ID 4, 7, 8) had progressed somewhat on the CGI-I in the follow-up period, but were still classified as non-responders. The study was approved by the local county Ethical Committee and by the Danish Data Protection Agency and all parents signed an informed consent form. Procedure The manualized Cool Kids program (Rapee et al. 2000) consisted of 10 weekly 2-h sessions in groups of five to seven youths and their parents. The main treatment components were psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring and gradual exposures. Prior to the individualized treatment, a new case formulation and treatment plan was worked out for each youth. Case formulations were also created prior to the manualized CBT, but they were not systematically used in the treatment. Most often, no major changes were made, but additional information was added, especially as to reasons for non-response in the manualized CBT. The therapist from the youth’s manualized treatment provided a draft of the new case formulation and treatment plan that was later discussed at a clinical staff meeting. Possible obstacles to treatment progress as well as length of treatment were also considered in that meeting. At a succeeding meeting with the family, the therapist presented an easy to grasp version of the proposed new case formulation and treatment plan, which the families were encouraged to comment on. Their suggestions, if any, were taken into account in the final, agreed-upon formulation and treatment plan. The individualized treatment was based on CBT principles. For youths with a primary SoP diagnosis (ID 1–6), disorder-specific components were added to therapy, such as behavioral experiments with video-feedback (see Clark 2001) and social-skills training exercises. Parents of youths with a primary separation anxiety disorder (SAD; ID 7–11) were encouraged to use contingency management, in order to promote youths’ independence and brave behavior (see Silverman and Kurtines 1999). Youths with an ADHDsymptomatology (ID 2, 4, 8, 13) received extra help in creating detailed weekly plans of the exposure exercises the youths needed to complete. Youths with a comorbid 123 506 J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25:503–517 Table 1 Demographic characteristics and categorical outcomes of manualized and individualized treatments Manualized treatment Pre-treatment Individualized treatment Post-treatment Diagnoses (CSR) 3-month F/U CGII Diagnoses (CSR) CGII Post-treatment 3-month F/U Diagnoses (CSR) Diagnoses (CSR) ID Gender, age Diagnoses (CSR) CGII CGII 1 M, 12 SoP (5), OCD (4) SoP (4) 3 SoP (5) 3 SoP (4) 2 OCD (4) 2 2 M, 10 SP (6), GAD (5), SAD (6), ADHD (4) SoP (4), SP (4) 2 SoP (6), SP (4), ADHD (4) 3 – 1 ADHD (4) 1 3 M, 15 SoP (7) SoP (5) 3 SoP (6) 3 – 1 SoP (4) 2 4 F, 14 SoP (7) SoP (7) 4 SoP (7), ADHD (4) 3 SoP (5) 3 – 1 5 F, 16 SoP (8), GAD (5) SoP (7) 3 SoP (7) 3 SoP (5) 3 SoP (5) 3 6 M, 15 SoP (7), DD (6) 4 SoP (7) 4 SoP (7) 3 SoP (7) 4 7 F, 12 SoP (7), GAD (4), DD (5) SAD (6), SP (5), GAD (5), MDD (4) SAD (6) 4 SAD (6) 3 SoP (5) 3 – 1 8 F, 13 SAD (8), GAD (6), PD (5), ADHD* SAD (7), GAD (6), MDD (6) 5 SAD (6) 3 GAD (4) 1 – 1 9 F, 9 SAD (7) SAD (6) 3 SAD (7) 3 – 1 – 1 10 F, 16 AP/PD (6), GAD (4) – 1 SAD (5), GAD (4), AP/PD (4), DD (4) 3 DD (4) 2 – 1 11 M, 10 SAD (6), SP (5) SAD (5) 3 SAD (4) 3 – 1 – 1 12 M, 7 OCD (4) – 1 OCD (7) 3 OCD (4) 2 – 1 13 F, 17 GAD (8), PD (7), SP (7), DD (6) ADHD* GAD (5), SP (4) 3 GAD (4), SP (4), ADHD (5), DD (5) 3 – 1 PD (6) 3 14 F, 9 SP (6), GAD (4), SAD (4) SP (6) 3 SP (6), GAD (6), SAD (4) 3 SP (4) 3 – 1 CSR, clinical severity rating; CGI-I, Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement Scale; SoP, social phobia; SAD, separation anxiety disorder; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; SP, specific phobia; AP/PD, agoraphobia with panic disorder; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder; DD, dysthymic disorder * Diagnosis given from psychiatric assessment prior to therapy start mood disorder (ID 10, 13) were encouraged to complete a positive events diary and arrange more enjoyable activities in their daily lives. Problems in families that inhibited youths’ treatment progress, such as an overprotective parenting style (ID 3, 5, 9, 11–14) and parental problems or conflicts (ID 4, 7, 8, 10), were also addressed. Furthermore, meetings with the therapist, the family and youths’ teachers were arranged, when needed (ID 1, 2, 5). Table 2 presents the most common problem areas identified among the youths during the manualized treatment, with the respective treatment elements added in the individualized treatment. Therapy was most often scheduled to take place in 10 weekly sessions, but in three cases (ID 3, 8, 9) 6 or 8 sessions were offered, often with a 2-week interval between sessions. The possibility of further sessions was left open; in two cases (ID 5, 6) 10 additional sessions were offered. Thus, the number of therapy sessions ranged from 6 to 20 (M = 11.14, SD = 4.13). The individualized intervention was conducted by one of the Anxiety Clinic’s psychologists, most commonly the same therapist that had 123 led the manualized treatment. All three therapists had prior experience in CBT for youths with anxiety disorders. The two therapists with less clinical experience received weekly supervision by the third therapist, who was specialized in CBT. For educational purposes, a graduate student attended therapy sessions and sometimes helped the youth with his/her exposure exercises. A case vignette of a 13-year old girl with a primary SAD (ID 8) shown in the Appendix illustrates the course of the two treatments and is accompanied by the case formulation as presented at the clinical staff meeting and the family. Measures Primary Outcome Measures Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Parent and Child Versions (ADIS-IV-C/P) The ADIS-IV-C/P (Silverman and Albano 1996) is a semi-structured interview for diagnosing anxiety disorders in youths based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25:503–517 507 Table 2 Problem areas and treatment elements of individualized treatment Problem areas in manualized treatment Treatment elements of individualized treatment Therapy Therapy Group format is anxiety provoking Therapy is conducted in individual setting Therapy not targeted to youths’ specific symptomatology Disorder specific treatment (e.g. in case of SoP: in vivo exposures with video-feedback, social skills training) Youth Youth Cognitive difficulties, youth unable to do cognitive restructuring Assistance in and simplification of cognitive restructuring, greater emphasis on exposures Youth lacks motivation to work on anxiety, seem ambivalent about engaging in therapy work Motivation talk (e.g., youth estimates the extent to which they believe in: 1. own capabilities, 2. appropriate timing, 3. treatment) Avoidance (overt or subtle) of anxiety and use of safety behaviours Practice relaxation exercises and assist youth in handling anxiety feelings and staying in situation until anxiety subsides School refusal or difficulties in attending school systematically Network meetings with school and planning of a gradual involvement in school after cooperating with teachers Depressive symptomatology and difficulties handling pressure Therapy starts with behavioral activation through very easy exposures and completion of positive diary Family Family Lack of systematic homework completion Detailed homework planning and close follow-up, problem solving Overprotective parenting, parents have difficulties setting demands to their child Parents made aware of consequences of behaviors through guided discovery, instructed in contingency management Parental psychopathology Problematic family issues (e.g., lack of resources/time for parents to practice with youth, parents disagree on how to handle youth’s symptomatology, parent–child conflicts) Parents refferred to treatment elsewhere Closer examination of family issues from which different interventions may follow, parents are involved in treatment in various ways (e.g., individual parent sessions, sessions with both parents and child) 4th edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association 1994). All disorders are given a clinical severity rating (CSR) from 0 (no interference) to 8 (extreme interference), with severity ratings of 4 and above indicating the presence of a disorder. Psychologists or trained and supervised graduate students conducted the ADIS-IV interviews (see Arendt et al. 2015 for further information). The most impairing diagnosis was considered to be the primary diagnosis. For the individualized intervention, the primary diagnosis was considered to be the one that was assessed at the 3-month follow-up to the manualized treatment. ADIS assessors were blinded at post and follow-up assessments to the youths’ prior diagnoses. Previous studies have found that ADIS-IV-C/P possesses favorable psychometric properties (Silverman et al. 2001; Wood et al. 2002). A reliability check was conducted in the RCT (Arendt et al. 2015), where one of two trained assessors watched and rated a total of 22 (20.2 %) of the video-recorded baseline interviews. Comparing these new assessments to the original, the interrater reliability (j) for the primary anxiety diagnosis was .77, and the interclass correlation coefficient for the CSR of the primary anxiety diagnosis was .69 (twoways mixed for individual raters, consistency). Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement Scale (CGII) The CGI-I (Guy 1976) is a clinician administered 7-point Likert-type scale, the seven points correspond to the following descriptions: 1: very much improved, 2: much improved, 3: minimally improved, 4: no change, 5: minimally worse, 6: much worse, 7: very much worse. A score of 1 or 2 reflects a substantial, clinically meaningful decrease in the primary anxiety disorder, while changes in other disorders are also considered. A score of 2 may be given in case of the presence of a mild disorder (CSR 0–4). The CGI-I is commonly used in clinical trials to define response to treatment and it has been found to be sensitive to change through treatment (Zaider et al. 2003). The CGI-I was rated by the therapist of the preceding treatment (manualized or individualized) after consulting changes on the ADIS, but without knowledge of youths’ and mothers’ reports on anxiety levels. A substantial agreement was found (j = .72) between CGI-I non-response and the presence of the primary diagnosis at the 3-month follow-up to the manualized treatment, when non-responders were identified. Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS-C/P) The SCAS was completed by youths (SCAS-C; Spence 1997) and mothers (SCAS-P; Nauta et al. 2004). SCAS-C consists of seven subscales for specific anxiety diagnoses: social phobia, panic disorder and agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, separation 123 508 anxiety disorder, and specific phobia (fear of physical injury). It has 38 items and six positive filler items, rated 0 (never) to 3 (always). In the current study only the total score of the subscales added together was used (range 0–114). The Danish translation of the SCAS-C has demonstrated excellent internal consistency for the total scale (a = .89) in a sample of youths with anxiety disorders and good test–retest reliability after 2 weeks (r = .84) and 3 months (r = .83) in a community sample (Arendt et al. 2014). The SCAS-P, completed by mothers, contains the same items as SCAS-C, except for the six positive filler items, and is scored in the same way. The Danish translation of SCAS-P has demonstrated good internal consistency for the total scale (a = .87) in a sample of parents of youths with anxiety disorders and good test–retest reliability after 2 weeks (r = .88) and 3 months (r = .81) in a community sample (Arendt et al. 2014). Internal consistency in the RCT sample (Arendt et al. 2015) for the total scale was excellent for SCAS-C (a = .90) and for SCAS-P, completed by mothers (a = .89). Secondary Measures Children’s Life Interference Scale (CALIS-C/P) The CALIS is designed to measure life interference and impairment experienced due to anxiety (Lyneham et al. 2013). All items are rated from 0 (not at all) to 4 (a great deal). The child version (CALIS-C) consists of nine items that examine the impairment experienced due to anxiety in several areas (e.g., how much do fears and worries make it difficult for you to do the following things? a. getting on with parents; b. getting on with brothers and sisters; c. being with friends outside of school…). The parents’ version (CALISP), completed by mothers in the study, consists of seven additional items that examine the extent to which youth’s anxiety interferes with parents’ own life (e.g., how much do your child’s fears and worries interfere with your everyday life in the following areas: a. your relationship with your partner, or a potential partner; b. your relationship with extended family; c. your relationship with friends…) attributed to the youth’s anxiety. In the current study only ratings for the combined measure of overall interference are reported (possible score range CALIS-C: R = 0–36, CALIS-P: R = 0–64). The scale has demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency on subscales for both youth (a range = .70–.84) and parent ratings (a range = .75–.90) and moderate stability for a 2-month retest period (r range = .62–.91; Lyneham et al. 2013). In the RCT study (Arendt et al. 2015) the Cronbach’s a was .81 for youthreported and .83 for mother- reported overall interference with the youth’s life and .87 for interference on mothers’ life. Experience of Service Questionnaire (ESQ) The ESQ is a measure assessing youths’ and parents’ satisfaction with 123 J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25:503–517 the treatment (Attride-Stirling 2002). The items are rated with 0 (not true), 1 (partly true), or 2 (true). The youth version consists of 7 items (e.g., the treatment helped me; after therapy I felt more like being with family and friends…), and mothers’ version of 10 items (e.g., the treatment helped my child; I was able to change my behavior towards my child in a positive way…), while the parent version has an additional two questions to comment on what they liked about the treatment and what could be improved. Administration of Measures Measures of outcome were administered pre- and posttreatment, and at 3-month follow-up in both the manualized and the individualized intervention (3-month follow-up to the RCT was pre-treatment for the individualized treatment). At the 12-month follow-up of the individualized treatment, families completed only the SCAS and the CALIS, while the ESQ was administered only at post-treatment in both interventions. All questionnaires were electronically administered. Families were sent an e-mail with a link, and in case of non-reply, they received 3 weekly reminders, followed by a phone call after 4 weeks. Statistical Analysis Pre-post and pre-3 month comparisons of the individualized treatment were analyzed, examining: (1) the number of participants responding to treatment (CGI-I \ 3); (2) the number of participants free of diagnoses (primary and all); (3) the number of participants showing statistical and clinical significant change on the SCAS-C/P; and (4) the degree of change on continuous outcome measures (CSR, SCAS-C/P, CALIS-C/P). Statistical and clinical significant change was calculated according to the Jacobson and Truax (1991) method. In order for youths to show statistical significant change, the change in scores had to be greater than the calculated reliable change index (RCI) and in order to show a clinical significant change, in addition to the statistical significant change, they also had to score below the cut-off point between anxious (clinical) and nonanxious (norm) youths after the individualized treatment: CScut-off = [(SDnorm 9 Mclinical) ? (SDclinical 9 Mnorm)]/ (SDnorm ? SDclinical). The clinical cut-off and RCI values were calculated using Danish community and clinical norms split into age groups (7–12 and 13–17 years) and gender (see Arendt et al. 2014, Table 7, p. 953). Maintenance of treatment outcome from post-treatment to 12-month follow-up was examined on SCAS-C/P and CALIS-C/P. Outcomes on the continuous measures were analyzed by t-tests for related samples and Cohen’s d effect size was computed based on change score values 36.93 (14.36) 13.00 (7.96) 31.93 (15.64) SCAS-P CALISC CALIS-P 26.79 (16.35) 10.00 (8.03) 27.07 (10.55) 24.38 (16.03) C/P = 13/14 6.43 (3.16) 28.57 (14.57) 10.14 (7.5) 27.14 (10.64) 23.5 (9.54) N = 14 8.07 (3.40) 16.79 (11.57) 8.17 (6.78) 17.00 (9.75) 15.17 (8.93) C/P = 12/14 3.93 (2.95) 2.86 (2.21) N = 14 15.23 (12.15) 5.75 (4.16) 17.77 (8.15) 14.17 (9.52) C/P = 12/13 3.29 (3.54) 2.36 (2.17) N = 14 3-month F/U 17.50 (13.35) 4.64 (3.70) 21.29 (13.11) 15.36 (10.23) C/P = 11/14 – – N = 14 12-month F/U 3-month follow-up to manualized * p \ .05; ** p \ .005, two tailed a t(12) = 4.69**, d = 1.30 t(11) = 3.12*, d = .90 t(11) = 1.14, d = .33 t(13) = 3.87**, d = 1.03 t(13) = 3.53**, d = .98 t(11) = 4.17**, d = 1.20 t(13) = 3.43**, d = .92 t(13) = 6.15**, d = 1.64 Pre- 3-month F/U t(13) = 3.02*, d = .81 t(11) = 3.63**, d = 1.05 t(13) = 3.10*, d = .83 t(13) = 6.64**, d = 1.78 Pre- post-treatment Test statistics of individualized treatment CSR, Clinician Severity Rating (ADIS); SCAS, Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale; CALIS, Child Anxiety Life Interference Scale C = youth report, P = mother report 41.00 (16.65) N = 14 12.36 (5.39) 5.93 (1.07) N = 14 N = 14 4.93 (2.24) N = 14 6.43 (1.22) Pretreatmenta Posttreatment Pretreatment SCAS-C All CSR Primary CSR Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Posttreatment Individualized treatment Manualized treatment Table 3 Continuous outcomes of manualized and individualized treatments t(13) = -.16, d = -.04 t(10) = 2.38*, d = .72 t(13) = -1.17, d = -.31 t(10) = .00, d = .00 – – Post- 12-month F/U J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25:503–517 509 123 510 (Borenstein et al. 2009). Statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21. Results Outcomes on a Group Level Table 1 shows categorical outcomes following the manualized and the individualized treatment. As assessed by the CGI-I following the individualized treatment, nine youths (64.3 %) had responded at post-treatment, and eleven (78.6 %) at the 3-month follow-up. After the individualized treatment, eight (57.1 %) were free of their primary diagnosis and six (42.9 %) were free of all anxiety diagnoses. At the 3-month follow-up, 11 (78.6 %) were free of their primary diagnosis and nine (64.3 %) were free of all diagnoses. Table 3 shows the means and standard deviations on the continuous measures, as assessed following both interventions, together with the test statistics for the pre-post, pre-3 months and post-1 year follow-up comparisons for the individualized treatment. The CSR for the primary anxiety diagnosis, the CSR for the sum of all anxiety diagnoses and the anxiety reported by youths and mothers (SCAS-C/P) all showed a significant decrease from pre- to post-treatment and from pre- to 3-month follow-up, with large effect sizes (d = .81–1.78). A significant reduction was seen in life interference from pre- to post-treatment according to mothers, but not youths, while a significant change from pre-treatment to the 3-month follow-up was seen on both self-reports (CALIS-C/P). The treatment gains of the individualized treatment remained stable from post-treatment to the 1-year follow-up, with no significant change on the anxiety levels (SCAS-C/P) or the life-interference according to mothers, only youths reporting a significant decrease on CALIS-C. Outcomes on an Individual Level As shown in Table 1, three of the non-responders (ID 4, 7, 14) identified after the individualized treatment, subsequently responded at the 3-month follow-up. At the followup two of the youths (ID 5, 6) had been non-responders since post-treatment, while the third non-responder (ID 13) had relapsed in the follow-up period. After the individualized treatment, two of the six youths (ID 2, 3) with a primary SoP diagnosis had remitted from their primary diagnosis, while all five youths with a primary SAD diagnosis (ID 7–11) had. At the 3-month follow-up, the youths who had not remitted from their primary diagnosis (ID 1, 2, 4) all had a primary diagnosis of SoP. 123 J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25:503–517 In Fig. 1 the self-reported anxiety levels are illustrated for the manualized (T1–T3) and the individualized (T3– T6) treatment for individual participants. Clinical cut-offs are shown in the figure, along with statistically significant changes for the individualized treatment. A significant decrease in anxiety symptoms was found at post- treatment (T4) for six youths (ID 2, 4, 5, 8, 11, 14) on SCAS-C, all of them but one (ID 13) also having shown a clinically significant change. Eight youths (ID 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 13, 14) showed a statistically and clinically significant change on SCAS-P. A significant increase in anxiety symptoms was found for one youth (ID 12) on SCAS-P. At 3-month follow-up (T5), when compared to pre-treatment, a significant decrease in anxiety symptoms was found for six of the youths (ID 4, 5, 7, 8, 11, 14) on SCAS-C, all of them but one (ID 4) also having shown a clinically significant change. Four youths (ID 4, 6, 8, 14) showed a statistically and clinically significant change on SCAS-P. A significant increase in anxiety was found for two youths (ID 7, 14) on SCAS-P. Families’ Satisfaction with Treatment After the individualized treatment, almost all of the youths (91.7 %) and all mothers indicated it was true that ‘‘treatment helped the youth’’, while the corresponding percentages after the manualized treatment were lower (youths 69.2 %, mothers 71.4 %). Youths’ evaluation of the statement ‘‘I trusted my therapist’’ as true rose from 85 % following the manualized treatment to 100 % following the individualised treatment, while twice as many youths believed it was true that ‘‘after therapy I felt more like being with family and friends’’ following the individualized as opposed to the manualized treatment (67 vs. 31 %). Among mothers, the percentage who believed it was true that ‘‘during therapy I managed being able to change my behavior towards my child in a positive way’’ rose to 79 from 64 % that was following the manualized treatment. Most families described how the manualized treatment had been helpful, as it offered them some techniques (e.g., It was really good to get some techniques that I had been missing for a long time and was starting to be desperate) and many families experienced the group setting of therapy as positive (e.g., It was nice and deliberating not to be the only ones with problems), but they felt it had not been sufficient (e.g., It has been too short and there was not enough time…we are afraid we cannot use the techniques on our own after so little time), while after the individualized treatment they got the last bit they were missing: (e.g., It gave us the last bit of understanding of the tools applicability). J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25:503–517 Fig. 1 Self-reported changes in anxiety levels in manualized and individualized treatments. Note T1 = pre manualized, T2 = post manualized, T3 = 3month F/U manualized/pre individualized, T4 = post individualized, T5 = 3-month F/U individualized, T6 = 1year F/U individualized. *Statistical significant change on SCAS-C; statistical significant change on SCAS-P. – Change in negative direction 511 SCAS-C SCAS-P _ _ SCAS-P cut-off … SCAS-C cut-off 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 ID. 1 T1 T2 T3 T T4 T5 T6 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 ID. 3 T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 T6 ID. 5 T1 T2 T3 T4* † T5* T6 ID. 7 T1 T2 T3 T4 T5* T6-† ID. 9 T1 T2 T3 T T4† T5 T6 -† 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 ID. 2 T1 T2 T T3 T4* † T6 -* † T5 ID. 4 T1 T2 T T3 T4* † T5* † T6 T5† T6 T5* † T6 ID. 6 T1 T2 T T3 T4 ID. 8 T1 T2 T3 T T4* † ID. 10 T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 T6 123 512 J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25:503–517 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 ID. 11 T1 T2 T3 T4* † T5* T6 ID. 13 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 ID. 12 T1 T2 T3 T4 -† T5 T6* ID. 14 Fig. 1 continued Discussion The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of an individualized case formulation-based CBT intervention for youths with anxiety disorders, who had not responded to a manualized group CBT. Nine of the 14 youths responded to the individualized treatment, as measured on the CGI-I at post-treatment, and this number increased to 11 at the 3-month follow-up. Youths’ anxiety levels decreased significantly with large effect sizes after the individualized treatment (post-treatment and 3-month follow-up). The positive outcomes remained stable until the 1-year follow-up. Even though all outcome measures showed positive effects on a group level, when examined on an individual level, the clinicians’ evaluation (ADIS-IV, CGI-I) was not always in agreement with the self-reported changes in anxiety (SCAS-C/P). For instance, three of the non-responders, identified after the individualized treatment (ID 4, 5, 14), reported decreased anxiety levels that were statistically and clinically significant. Youths and mothers reported similar changes in anxiety symptoms during the two interventions; the greatest differences often being prior to the manualized treatment (ID 6, 8, 9) and at the 1-year follow-up to the individualized intervention (ID 2, 7, 14). Besides a decrease in anxiety symptoms, the individualized treatment contributed also to a decrease in perceived life-interference due to anxiety. Usually impairment brings clients to seek treatment (Angold et al. 1999) and a decrease in life-interference is likely to have the strongest impact on satisfaction with the treatment (Lyneham et al. 123 2013). The families were highly satisfied with the individualized treatment, which they believed had helped the youths. Compared to the manualized treatment, more youths liked being with family and friends after the individualized treatment, and more mothers believed they had been able to change their behavior towards their child in a positive manner. The participants most commonly had a primary SoP diagnosis or a SAD diagnosis. Youths with primary SAD appeared to benefit a lot from the individualized treatment, since all of them were diagnosis-free at post-treatment and at the 3-month follow-up. Therapists often involved parents of youths with SAD to a large extent in treatment, since youths’ symptomatology was directly related to their parents. Instead of reinforcing and maintaining the youths’ anxiety by reassuring them nothing bad would happen to them, parents were guided on how to encourage their child to become more independent. Parents would encourage their child to use the treatment techniques, while elements of contingency management and transfer of control were emphasized. This kind of active parental involvement has also earlier been associated with better long-term outcomes (Manassis et al. 2014). In contrast, three of six youths with a primary SoP diagnosis still had their primary diagnosis at the 3-month follow-up. SoP has been associated with worse treatment outcomes after manualized CBT (e.g., Hudson et al. 2015) and this was also found for the participants of the manualized treatment from which non-responders were identified for our study (Arendt et al. 2015). The individual setting enabled the addition of disorder-specific techniques for youths with SoP, such as video-feedback (Harvey et al. J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25:503–517 2000) and social skills training (Beidel et al. 2005). Even though some of the youths were not diagnosis-free after the end of the individualized treatment, the severity of their anxiety had in most cases decreased. The three non-responders, who even after the individualized treatment and the additional 3 months after therapy still had not responded to treatment, were among the older participants in the study and two of them had been offered 20 sessions of individualized CBT each. Following information collected after the conclusion of therapy, parents of two of the youths reported that their child had been diagnosed with another disorder (epilepsy and borderline personality disorder) that could better explain their symptomatology. Overall, most of the youths classified as non-responders, who underwent additional individualized treatment, had to some degree progressed during the manualized treatment (i.e., most common CGI-I rating was minimally improved). Families were able to learn techniques in a cost-effective format and might have profited from non-specific group factors (Yalom 1975), such as group cohesiveness, interpersonal learning and ‘‘universality’’ (not being alone with the problems). However, the families experienced the manualized treatment as too short and felt unable to continue working on their own, while the therapy format had not allowed the clinician to include additional treatment elements in case of non-anxiety difficulties, or work more closely with every family. The individualized therapy allowed for the flexibility to tailor treatment components to each family’s specific needs. The focus of the individualized treatment was to enhance the families’ understanding of the techniques, in order for them to be able to work more independently, and to increase the amount of time youths spent on exposures, which is considered the primary active ingredient of anxiety treatment (Barlow 2002; Crawley et al. 2012). This was done through in vivo exposures during sessions, which also allowed clinicians to address any subtle avoidance behaviors and coach parents on how to respond to their child when anxious by using the treatment skills. Clinicians also emphasized that youths should carry out exposures between sessions; following up more closely on the families’ homework, problem solving with them when obstacles were encountered, and working on the parents’ tendency to overprotect their child, thereby creating natural exposures for the youth. Results of our study must be viewed in the light of methodological limitations, as there was a lack of a control group, a small sample size and the CGI-I assessments were conducted by the therapists. Nevertheless, our study holds promising findings of clinical relevance, as it showed how non-responders to manualized CBT may respond to treatment, when offered CBT tailored to their needs. In case of non-response to CBT, when examining the factors, which may influence treatment gains, decision-making maps 513 could facilitate this process (see Marder and Chorpita 2009). When clinicians create or revise the individual case formulations, information from the first treatment can be integrated, facilitating the planning of the individualized treatment. This approach encourages a collaborative stance towards the family, while therapists can flexibly address difficulties families may encounter during therapy. What seemed to contribute to the youths’ response to treatment was the enhancement of their exposure to anxiety-provoking situations. In case of non-response to this extra intervention, clinicians may need to consider whether another primary disorder than anxiety better explains the youths’ difficulties and another treatment form is more suitable. Further research is needed to develop empirically supported guidelines on the development of case formulations and to examine their effectiveness among non-responding youths with anxiety disorders. In conclusion, the individualized case formulation-based CBT overall proved to be effective in treating youths with anxiety disorders, who had not profited sufficiently from manualized CBT. The majority of youths responded to the treatment and most of the youths were free of their anxiety diagnoses at post-treatment and the 3-month follow-up. The self-reported anxiety and life interference showed significant changes with large effect sizes following the individualized treatment and the positive outcomes were maintained at the 1-year follow-up. Acknowledgments The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of this research by TrygFonden (Grant ID No. 10691), who had no further role in the study or in the decision to submit the article for publication. Furthermore, the authors would like to thank Lisbeth Jørgensen, Signe Matthiesen, Kristian Bech Arendt, and Marianne Bjerregaard Madsen for their contributions to the implementation and evaluation of the study. Appendix: A Case Vignette Presenting Picture Lise (fictitious name; ID 8) was a 13-year old girl, who attended 6th grade and lived with both of her parents. She was the youngest of four children, one of which had moved from home. Her parents contacted the Anxiety Clinic because Lise was afraid something horrible would happen to her mother. For instance, she was afraid that her mother might die in a car accident or from a heart attack. This negatively affected her school attendance, social activities with peers and the family life, because she wanted to be with her mother at all times. From the diagnostic interview, it was concluded that Lise had a primary SAD diagnosis, a comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder (see Table 1). Parents reported feeling stressed, since both 123 514 J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25:503–517 A PERSONAL MAINTAINING FACTORS Psychological factors - Avoidance behaviour - Anxiety escalates fast and youth is therefore unable to use treatment techniques - Cognitive difficulties due to comorbid ADHD - Immature defence mechanisms (idealization of mother and devaluation of father) contribute to conflicts at home PERSONAL PROTECTIVE FACTORS Psychological factors - Normal intelligence Anxiety CONTEXTUAL PROTECTING FACTORS Treatment system factors - Family accepts there is a problem and are committed to resolving the problem - Good relation to therapist in Clinic CONTEXTUAL MAINTAINING FACTORS Family system factors - Father attends treatment Family system factors - Stressed parents, difficult to prioritize practicing between sessions - Problematic reinforcement of avoidance behaviour (lack of school attendance is rewarded with time with the mother) - Problematic relation to father - Overinvolved mother-child relation Social network factors - Good relations to the rest of the family - Good school placement B WHAT WE NEED TO DO MORE - Create realistic plans - Choose few techniques that work - Use techniques consistently - Complete more homework (daily plans) - Follow-up on homework very closely in sessions -Practice staying in situation until anxiety subsides - Give rewards consistently - Spend time with both mum and dad - Work on becoming more independent - Dad and mum learn how to let go in a good way PROTECTIVE FACTORS Anxiety -Smart girl - Liked by others - Creative - Works well with the techniques - Therapy was successful– it works - Parents are supportive - Good relationship to older sisters - Good school that is supportive - Friends Parents’ suggestions: - Mother spends more time outside the house - Work on Lise’s catastrophic thoughts Fig. 2 Case formulation of Lise. a Case formulation as presented at clinical staff meeting. b Case formulation as presented to family were working fulltime, and three of their children had an ADHD diagnosis that demanded a lot of attention. History At the intake interview, parents reported that Lise showed the first signs of separation anxiety when she 123 had to start at early childhood care. Her difficulties escalated in the 3rd grade, when she stayed home from school for half a year. She underwent psychiatric evaluation that resulted in an ADHD diagnosis for which she received medication. Lise also saw a psychologist for 12 sessions and was helped to gradually attend a new school. Nevertheless, she was only able to attend the J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25:503–517 new school occasionally and only if her mother accompanied her. Manualized Treatment Lise had difficulties completing tasks in the group, as because of her ADHD she became easily distracted. Furthermore, the family had difficulties completing exercises on cognitive restructuring between sessions, because Lise became irritated with her father, when he posed questions that were meant to challenge her erroneous attributions, as she felt he did not take her difficulties seriously. On the other hand, the mother had a tendency to reassure Lise, instead of challenging her worries. As the mother herself reported, sometimes it was easier to stay home from work, rather than having to deal with an extremely anxious child. Therefore, the parents had very different ways of handling her anxiety. Lise idealized the mother and devaluated the father, demanding for instance that he (not the mother) should sit behind the wheel, so he would be the one killed in a possible car accident. The family was introduced to the principles of graduated exposures, but it was difficult for them to practice systematically, because of a hectic and chaotic everyday in the family. The therapist reported having difficulties to follow-up on the family’s work as closely as needed, while there was not enough time to address the problematic family dynamics in a group setting. Outcome of Manualized Treatment Lise made some progress during the manualized treatment, as she started spending more time with her father and on ‘‘good days’’ she would go to school alone. She and her mother reported decreased anxiety levels after the end of treatment (see Fig. 1). Nevertheless, the diagnostic interviews at posttreatment and at the 3-month follow-up indicated she had not remitted from her anxiety diagnoses and she was classified as a non-responder (see Table 1), so she was offered further treatment. Lise’s case formulation, as presented at the clinical staff meeting and the family, is displayed in Fig. 2. Individualized Treatment The treatment consisted of eight sessions, the first four every week and the remaining every other week. From therapy start, the family’s homework was closely monitored, the therapist following up at each session the entries on exposure work made by the family, in the booklet they were given. Lise had difficulties with completing the exposure exercises due to her anxiety escalating very rapidly, making it hard for her to use the techniques. Interoceptive exposures were practiced in the session and Lise at first laughed when seeing the therapist 515 hyperventilating, then when she started to hyperventilate, she felt dizzy, got scared and thought: this will end badly. She was encouraged to challenge her catastrophizing thoughts and she got a cue card with the alternative thought: I have some techniques I can try out. I am sure I can make this stop. Lise made progress in staying home for longer intervals and when she would get thoughts such as: what if they never come home? They could be dead, she tried to ignore them by focusing on what she was doing. When she got anxious in school, she reported tackling the butterflies in the stomach by trying to breathe more calmly, as she was taught to do in therapy sessions. She commented on her progress: Now I am a bit more like the others, doing the same things as them. Nevertheless, Lise would easily become discouraged and it was hypothesized that the ADHD contributed to her difficulties in having an overview of her progress and drawing learning from her experiences, negatively impacting her motivation. She was therefore given a success-diary in which she would write down her success-experiences and what she had learned. The individualized format allowed the therapist to spend some time with the parents alone during the sessions, where behaviors that contributed to the maintenance of Lise’s anxiety were discussed. During those sessions, a trained graduate student would conduct in vivo exposures with Lise, where she would practice taking the bus. The parents developed a more consistent way of handling her anxiety, assisting her in the implementation of techniques and praising her for bravery. Instead of creating ‘‘stepladders’’ of graduated exposures, they were presented with an alternative graphical presentation of behavioral experiments that was more flexible and easy for them to follow. Outcome of Individualized Treatment Lise made great progress during the individualized treatment, as she for instance became able to stay home alone for 2 h and she ended up taking the bus alone to school on a daily basis. At post-treatment and at the 3-month follow-up, Lise was classified as a responder (see Table 1). Self-reports showed that Lise and her mother experienced a significant decrease in anxiety levels, which remained low at the 3-month and at the 1-year follow-up assessments (see Fig. 1). The mother evaluated the therapy they had received: It [the individualized treatment] was intense…but also good. We had already learned the techniques and gotten a lot out of being together with the others. Now we needed to work more intensively and it was very good that it was always adjusted in order to fit exactly to what Lise needed. It wouldn’t have helped being in a group again…We needed this continuous monitoring in order to get to the bottom of 123 516 things…breathing exercises might for instance not be something all children need, but we couldn’t get any further, until Lise learned to tackle the symptoms. References American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Angold, A., Costello, E., Farmer, E. M., Burns, B. J., & Erkanli, A. (1999). Impaired but undiagnosed. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 129–137. doi:10.1097/00004583-199902000-00. Arendt, K., Hougaard, E., & Thastum, M. (2014). Psychometric properties of the child and parent versions of Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale in a Danish community and clinical sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28, 947–956. doi:10.1016/j. janxdis.2014.09.021. Arendt, K., Thastum, M., & Hougaard, E. (2015). Efficacy of a Danish version of the Cool Kids Program: A randomized waitlist controlled trial. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. doi:10. 1111/acps.12448. Attride-Stirling, J. (2002). Development of methods to capture users’ views of CAMHS in clinical governance reviews. Cambridge, UK: Commission for Health Improvement. Barlow, D. H. (2002). Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. Barrett, P. M., Lowry-Webster, H., & Holmes, J. (2000). The friends anxiety prevention program. Queensland: Australian Academic Press. Barrett, P. M., & Turner, C. (2000). FRIENDS for children: Group leader’s manual. Bowen Hills: Australian Academic Press. Beidel, D. C., Turner, S. M., Young, B., & Paulson, A. (2005). Social effectiveness therapy for children: Three-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 721–725. doi:10. 1037/0022-006X.73.4.721. Bodden, D. H. M., Bögels, S. M., Nauta, M. H., De Haan, E., Ringrose, J., Appelboom, C., & Appelboom-Geerts, K. C. M. M. J. (2008). Child versus family cognitive-behavioral therapy in clinically anxious youth: an efficacy and partial effectiveness study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 1384–1394. doi:10.1097/CHI. 0b013e318189148e. Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgens, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. West Sussex: Wiley. Carroll, K. M., & Rounsaville, B. J. (2008). Efficacy and effectiveness in developing treatment manuals. In A. M. Nezu & C. M. Nezu (Eds.), Evidence-based outcome research: A practical guide to conducting randomized controlled trials for psychosocial interventions (pp. 219–243). New York: Oxford University Press. Chorpita, B. F., & Daleiden, E. L. (2014). Doing more with what we know: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of clinical child and adolescent psychology, 43, 143–144. doi:10.1080/15374416. 2013.869751. Clark, D. M. (2001). A cognitive perspective on social phobia. In W. R. Crozier & L. E. Alden (Eds.), International handbook of social anxiety: Concepts, research and interventions relating to the self and shyness (pp. 405–430). London: Wiley. Compton, S. N., Peris, T. S., Almirall, D., Birmaher, B., Sherrill, J., Kendall, P. C., & Albano, A. M. (2014). Predictors and moderators of treatment response in childhood anxiety disorders: 123 J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25:503–517 Results from the CAMS trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82, 212–224. doi:10.1037/a0035458. Costello, E. J., Egger, H. L., Copeland, W., Erkanli, A., & Angold, A. (2011). The developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders: Phenomenology, prevalence, and comorbidity. In W. K. Silverman & A. P. Field (Eds.), Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents (2nd ed., pp. 56–75). New York: Cambridge University Press. Crawley, S. A., Beidas, R. S., Benjamin, C., Martin, E., & Kendall, P. C. (2008). Treating socially phobic youth with CBT: Differential outcomes and treatment considerations. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36, 379–389. doi:10.1017/ S1352465808004542. Crawley, S. A., Kendall, P. C., Benjamin, C. L., Brodman, D. M., Wei, C., Beidas, R. S., & Mauro, C. (2012). Brief cognitivebehavioral therapy for anxious youth: Feasibility and initial outcomes. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20, 123–133. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.07.003. Essau, C. A., Conradt, J., & Petermann, F. (2000). Frequency, comorbidity, and psychosocial impairment of anxiety disorders in German adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 14, 263–279. doi:10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_8. Guy, W. (1976). The Clinical Global Impression Scale. In ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology—revised (pp. 218–222). Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, ADAMHA, MIMH Psychopharmacology Research Branch. Harvey, A. G., Clark, D. M., Ehlers, A., & Rapee, R. M. (2000). Social anxiety and self-impression: Cognitive preparation enhances the beneficial effects of video feedback following a stressful social task. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 1183–1192. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00148-5. Hudson, J. L., Keers, R., Roberts, S., Coleman, J. R. I., Breen, G., Arendt, K., Eley, T. C. (2015). The genes for treatment study: A multi-site trial of clinical and genetic predictors of response to Cognitive Behaviour Therapy in paediatric anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54, 454–463. Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, 12–19. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12. James, A. C., James, G., Cowdrey, F. A., Soler, A., & Choke, A. (2013). Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6, 1–103. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004690.pub3. James, A., Soler, A., & Weatherall, R. (2005). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews,. doi:10.1002/ 14651858.CD004690.pub2. Kendall, P. C., Gosch, E., Furr, J. M., & Sood, E. (2008). Flexibility within fidelity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 987–993. doi:10.1097/CHI. 0b013e31817eed2f. Kerns, C. M., Read, K. L., Klugman, J., & Kendall, P. C. (2013). Cognitive behavioral therapy for youth with social anxiety: Differential short and long-term treatment outcomes. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27, 210–215. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.01.009. Kessler, R. C., Avenevoli, S., Green, J. G., Gruber, M., Guyer, M., & Merikangas, K. R. (2009). The national comorbidity survey adolescent supplement (NCS-A), III: Concordance of DSMIV/ CIDI diagnoses with clinical reassessments. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 386–399. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819a1cbc. Last, C. G., Hansen, C., & Franco, N. (1997). Anxious children in adulthood: A prospective study of adjustment. Journal of the J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25:503–517 American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 645–652. doi:10.1097/00004583-199705000-00. Legerstee, J. S., Huizink, A. C., van Gastel, W., Liber, J. M., Treffers, P. D. A., Verhulst, F. C., & Utens, E. M. W. J. (2008). Maternal anxiety predicts favourable treatment outcomes in anxietydisordered adolescents. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 117, 289–298. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01161.x. Legerstee, J. S., Tulen, J. H. M., Dierckx, B., Treffers, P. D. A., Verhulst, F. C., & Utens, E. M. W. J. (2010). CBT for childhood anxiety disorders: Differential changes in selective attention between treatment responders and non-responders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 162–172. doi:10.1111/j. 1469-7610.2009.02143.x. Liber, J. M., Van Widenfelt, B. M., Utens, E. M., Ferdinand, R. F., Van der Leeden, A. J., Van Gastel, W., & Treffers, P. D. A. (2008). No differences between group versus individual treatment of childhood anxiety disorders in a randomised clinical trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 886–893. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01877.x. Lundkvist-Houndoumadi, I., Hougaard, E., & Thastum, M. (2014). Pre-treatment child and family characteristics as predictors of outcome in cognitive behavioural therapy for youth anxiety disorders. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 68, 524–535. doi:10. 3109/08039488.2014.903295. Lyneham, H. J., Sburlati, E., Abbott, M., Rapee, R. M., Hudson, J., Tolin, D., & Carlson, S. (2013). Psychometric properties of the child anxiety life interference scale (CALIS). Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27, 711–719. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.09.008. Manassis, K., Lee, T. C., Bennett, K., Zhao, X. Y., Mendlowitz, S., Duda, S., & Wood, J. J. (2014). Types of parental involvement in CBT with anxious youth: A preliminary meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82, 1163–1172. doi:10. 1037/a0036969. Marder, A. M., & Chorpita, B. F. (2009). Adjustments in treatment for limited or nonresponding cases in contemporary cognitivebehavioral therapy with youth. In D. McKay & E. A. Storch (Eds.), Cognitive-behavior therapy for children: Treating complex and refractory cases (pp. 9–46). New York, NY: Springer. Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Shelli, A., Cui, L., & Swendsen, J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 980–989. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. Nauta, M. H., Scholing, A., Rapee, R. M., Abbott, M., Spence, S. H., & Waters, A. (2004). A parent-report measure of children’s anxiety: Psychometric properties and comparison with childreport in a clinic and normal sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 813–839. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00200-6. Perini, S. J., Wuthrich, V. M., & Rapee, R. M. (2013). ‘‘Cool Kids’’ in Denmark: Commentary on a cognitive-behavioral therapy group for anxious youth. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy, 9, 359–370. Persons, J. B. (1991). Psychotherapy outcome studies do not accurately represent current models of psychotherapy: A proposed remedy. American Psychologist, 46, 99–106. Rapee, R. M., Wignall, A., Hudson, J. L., & Schniering, C. A. (2000). Treating anxious children and adolescents: An evidence-based approach. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications. Reynolds, S., Wilson, C., Austin, J., & Hooper, L. (2012). Effects of psychotherapy for anxiety in children and adolescents: A meta- 517 analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 251–262. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.005. Silverman, W. K., & Albano, A. M. (1996). Anxiety disorder interview schedule for DSM-IV, child version. Silverman, W. K., & Kurtines, W. M. (1999). A pragmatic perspective toward treating children with phobia and anxiety problems. In S. W. Russ & T. H. Ollendick (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapies with children and families (pp. 505–521). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press. Silverman, W. K., Saavedra, L. M., & Pina, A. A. (2001). Test–retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 937–944. doi:10.1097/00004583200108000-00. Southam-Gerow, M. A., Rodriguez, A., Chorpita, B. F., & Daleiden, E. L. (2012). Dissemination and implementation of evidence based treatments for youth: Challenges and recommendations. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43, 527–534. doi:10.1037/a0029101. Spence, S. H. (1997). Structure of anxiety symptoms among children: A confirmatory factor-analytic study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 280–297. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.106.2.280. Taylor, S., Abramowitz, J. S., & McKay, D. (2012). Non-adherence and non-response in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 583–589. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2012. 02.010. Van der Leeden, A. J., van Widenfelt, B. M., van der Leeden, R., Liber, J. M., Utens, E. M., & Treffers, P. D. (2011). Stepped care cognitive behavioural therapy for children with anxiety disorders: A new treatment approach. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 39, 55–75. doi:10.1017/S1352465810000500. Weisz, J. R., Chorpita, B. F., Palinkas, L. A., Schoenwald, S. K., Miranda, I., Bearman, S., & the Research Network on Youth Mental Health. (2012). Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy treating depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in youth: A randomized effectiveness trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69, 274–282. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychia try.2011.147. Weisz, J. R., Ugueto, A. M., Cheron, D. M., & Herren, J. (2013). Evidence-based youth psychotherapy in the mental health ecosystem. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42, 274–286. doi:10.1080/15374416.2013.764824. Wergeland, G. J. H., Fjermestad, K. W., Marin, C. E., Haugland, B. S., Bjaastad, J. F., Oeding, K., & Heiervang, E. R. (2014). An effectiveness study of individual vs. group cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in youth. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 57, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2014.03.007. Wood, J. J., Piacentini, J. C., Bergman, R. L., McCracken, J., & Barrios, V. (2002). Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 31, 335–342. doi:10.1207/153744202760082595. Yalom, I. D. (1975). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books. Zaider, T. I., Heimberg, R. G., Fresco, D. M., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (2003). Evaluation of the Clinical Global Impression Scale among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Psychological Medicine, 33, 611–622. doi:10.1017/ S0033291703007414. 123 Copyright of Journal of Child & Family Studies is the property of Springer Science & Business Media B.V. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.