LESSONS

IN

NDEBELE

James

and

Pamela Felling

...... .....................................lili 441 |||1Т1Ш1|

Lessons in

NDEBELE

JAMES and PAMELA FELLING

Published in association with

The Literature Bureau

Longman Zimbabwe ™

Longman Zimbabwe (Pvt) Limited

Tourle Road, Ardbennie, Harare

Associated companies, branches and representatives

throughout the world

© J. Felling and P. Felling 1974

All rights reserved. No part of this publication

may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,

or transmitted in any form ot by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording

or otherwise, without prior permission of the

Copyright owner

First published 1974

Revised Edition 1987

ISBN O 582 61436 8

Printed by Mambo Press

Gweru

Contents

page

Introduction

1 Pronunciation

2 The verb

3 The noun: UM/ABA class

4 The noun: U /0 class

5 The object of the verb

6 Requests and commands; the imperative verb

7 Interjections and the question

8 The greetings

9 Interrogative adverbs

10 Present tense: use of the short and long forms

11 The negative verb: present tense

12 The noun: UM/IMI class

13 The noun: I LI/AMA class

14 The noun: ISl/IZI class

15 The noun: IN/IZIN class

16 The noun: ULU/IZIN class

17 The noun: UBU class

18 The noun: UKU class

19 Nouns of foreign origin

20 The locative demonstrative (here is)

21 Adverbs and relative stems

22 The verb: past tense

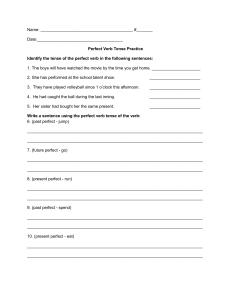

23 The verb: perfect tense

24 Different forms of the perfect tense

25 Stative verbs

26 The verb: future tense

27 Introducing vowel verbs

28 Introducing the subjunctive mood

29 Use of -BO (‘must’); the imperative with object concords;

the negative infinitive

30 Introducing the potential mood

31 The absolute pronoun

32 The stem -NKE (‘all’)

33 Verbs with two objects

34 The connective: LA- (and/with)

35 The instrumental NGA36 The locatives KU-, KO-, E37 The locative form of the noun

38 The possessive with nouns: 1

39 The possessive with nouns: II

40 Possessive pronouns

41 Adverbs with nouns and pronouns

42 The demonstrative pronoun

V

I

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

22

24

25

27

29

31

33

35

36

37

40

42

45

47

49

51

54

56

59

63

65

67

69

70

71

75

77

79

83

85

87

90

93

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

Adjective stems: I

Adjective steins: II

The relative concord

Relative clauses

The participial mood of the verb

Conjunctions with the participial mood

Conjunctions with the subjunctive mood

Reported speech and use of ‘ukuthi’

The copulative with nouns and pronouns

The passive form of the verb

Monosyllabic verbs

Vowel verbs (continued)

SA(stiU)

KA (not yet)

SE (now, then, already)

The future continuous tense and the future perfect tense

The past continuous tense (recent)

The past continuous tense (remote)

The past perfect tense (recent and remote)

The conditional verb and the use of ‘ngabe’

The potential mood (continued) and other ways of expressing

ability

64 Different forms of the verb stem

65 -DWA (alone), -PHI (which?) and the possessive pronoun

66 Comparison

67 Numbers and adverbs

68 The copulatives NGU- and YI- (continued)

69 The verb ‘ukuba’ (to be)

70 Expressions relating to time

71 Auxiliary verbs

72 Deficient verbs

73 ‘SE’ with the past continuous and past perfect tenses

74 Ideophones

75 Denoting sex and diminutives

General index

96

100

103

107

113

117

119

122

125

129

132

136

138

140

141

146

148

152

155

159

162

164

169

173

176

181

185

188

192

194

200

204

205

208

Introduction

This is not a book for linguists; it is for ordinary people. Its purpose is to

provide a series of lessons for English speaking people who have little

grammatical knowledge, but wish to learn the Ndebele language. I have

tried to make the lessons as clear and easy to read as possible, to build up

step by step an understanding of the structure of the language, and to

give students what they need to begin using it. Several years experience

of teaching Ndebele to English speaking students has helped me to

understand some of the needs and difficulties people experience.

For my husband’s part, many years of study and experience in trans­

lation work with African colleagues have given him a thorough and

detailed knowledge and appreciation of the language, thus providing

the material for these lessons. Someone who is studying the language for

the first time can be sure of learning true Ndebele, and a person who

already has some knowledge of the language will also find something

of interest here.

It is not possible to list our many Ndebele friends who have helped

indirectly with this book by discussing their language with us, but we

are very grateful to them. Special thanks go to Mr P. Mpofu of the

Rhodesia Literature Bureau, for his painstaking checking of every word in

this manuscript, and helpful comments. We would also like to thank the

members of the Ndebele Language Committee for their encouragement

and support.

Pamela Pelling

Lesson 1

Pronunciation

This lesson does not contain a study of the phonetics of the Ndebele

language; it is designed to help the student with pronunciation. Since

the language is written phonetically, once the vowel and consonant

sounds have been learnt, any word can be read.

Equivalents of sounds in Ndebele and English are often given to help

the beginner, but this practice can be misleading, as the way people

articulate English sounds varies greatly. It is essential for the student

to spend time with a Ndebele person, practising the speech sounds, and

imitating intonations of words and sentences.

In this lesson lists of words are given which the student should read

through with his African helper.There are also explanations of the use of

the speech organs (tongue, lips, and so on) for articulating the more

difficult Ndebele sounds.

I

THE VOWELS

All the vowels in Ndebele are articulated as one pure

diphthongs as in English.

e : ye

mama

(mother)

ehe

mfana

(boy)

hamba

(go)

(stay)

wena

sala

melela

(what?)

0 : woza

yiiu?

imizi

(villages)

isigodo

imini

(midday)

ogogo

(word)

inyoni

ilizwi

(person)

umuntu

umumbu (maize)

(a Zulu)

umZulu

(tortoise)

uflidu

sound; there are no

(yes)

(yes, with

approval)

(you)

(wait for)

(come)

(pole)

(grandmothers)

(bird)

II THE CONSONANTS

There is little difficulty in using the consonants found in the words listed

above, but some explanation is needed for other consonants.

1 Aspiration

An aspirated consonant is one which is followed by a rush of air. More

air is expelled than is usual when articulating English consonants, other1

wise the sound is similar. (You can test whether you are saying the as­

pirated consonants properly, by holding your hand in front of your

mouth to feel the air on it.)

Aspirated consonants are written with an ‘h’, to distinguish them from

non-aspirated consonants, which are not followed by this rush of air.

ph

th

kh

Aspirated

phapha

phepha!

phila

uthango

thenga

ulutho

ikhabe

ukhezo

ukhuni

(fly)

P

(sorry!)

(live)

t

(fence)

(buy)

(thing)

(water melon) k

(spoon)

(piece of

firewood)

Non-aspirated

impala

(impala buck)

impela

(indeed)

(life)

impilo

intango

(fences)

intengo

(price)

izinto

(things)

inkabi

(ox)

inkezo

(spoons)

inkuni

(firewood)

2 Voiced consonants

The term ‘voiced’ means that the consonant is articulated with a vibration

of the vocal chords. You will understand what is meant by this if you

compare the following:

Unvoiced: p

Voiced: b

t

d

k

g

f

V

Voiced 'k': As used in the examples above, ‘kh’ and ‘k’ are unvoiced.

There is a third way of pronouncing ‘k’, a little farther back in the mouth,

and with a slight voicing, so that it approaches the sound of ‘g’. This is

when ‘k’ is the initial vowel of the word, or comes between two vowels,

kade

(long ago)

pheka (cook)

ukufa (to die)

3 Explosive and implosive ‘b’

Explosive: bh : This is written with an ‘h’ to distinguish it from the

implosive ‘b’, but it is not aspirated. It is pronounced like the English ‘b’,

but more sharply,

bhala (write)

bhema (smoke)

ibhiza (horse)

Implosive: b : This is a very difficult sound to articulate: place

the lips together, and lower the larynx. Then when the lips are opened to

make the ‘b’, there should be a momentary intake of air, which gives the

‘b’ its distinctive character. Many people think it sounds slightly like V .

bala

(read)

beka

(put)

ibizo

(name)

4 Combinations of consonants

a) tsh : Compare with ‘ch’ as in ‘church’:

isitsha

(container)

tshetsha (walk quickly)

tshiya

(leave)

b) ng : This is a nasal sound; there are two ways of saying it,

according to the word in which it is found.

Compare with ‘ng’ in ‘singing’: Compare with ‘ng’ in ‘finger’:

ngaphi?

(where?)

amanga

Oies)

thenga

(buy)

ngaki?

(how many?)

ngejubane

(speedily)

ngena

(enter)

indingindi

(measles)

ingubo

(blanket)

c) ny : inyama (meat)

omunye (another person)

nyikinyeka (move)

d ) hi

: To make this sound, press the tip of the tongue on the front

ridge of the palate as when articulating T. Expel air, allowing it to escape

round the sides of the tongue, with friction.

isihlahla (tree)

kuhle

(well)

mhlophe (white)

buhlungu (painful)

e ) dl

: Make this sound using the same method as for ‘hi’, but use

the voice (as when articulating ‘d’).

ukudla

(food)

indlela

(path)

indlovu

(elephant)

indlu

(hut)

f ) kl

: This sound is made in a similar way to ‘hi’, but with the

tongue in a different position, as if articulating ‘g’.

klabalala (shriek)

klekla

(pierce the ear)

kloloda

(mock)

III THE CLICK SOUNDS

Three consonants are known as ‘clicks’, because of the sharp sound

produced by the suction as the tongue is withdrawn from the position

in which it has been pressed. The tongue must be positioned correctly for

all three, with the back of it pressed against the back of the soft palate,

the front of it pressed against the front ridge of the palate, and a depression

in between.

a) The dental click: written as ‘c’

Place the tongue in the position described above, with the tip of the

tongue against the teeth; release the tongue tip to make the click sound,

icansi

(mat)

cela

(ask for)

cina

(end)

cotsha

(peck)

isicucu

(piece)

b) The palatal click: written as ‘q’

Place the tongue in the position described for all three clicks, with the tip

of the tongue pressed hard on the front ridge of the palate; release the

tongue tip to make the click sound,

qaphela! (look out!)

qeda

(finish)

iqiniso

(truth)

qoqa

(collect)

quma

(cut through)

c) The lateral click: written a s ‘x’

Place the tongue in the position described for the palatal click; one side

of the tongue, which is pressed against the upper teeth, is released to

make the click sound,

xabana

(quarrel)

xexebula (peel off)

uxolo

(pardon)

ixuku

(crowd)

xwayisa (caution)

d) Aspirated, voiced and nasal forms o f the clicks

Each of the clicks may be pronounced aspirated (followed by a rush of

air), or voiced (with vibration of the vocal chords), or nasal (the air

passing out through the nose).

Aspirated

uchago

ichibi

chola

qha

iqhiye

isiqhotho

xhawula

ixhegu

xhuma

(milk)

(pool)

(grind finely)

(expresses

dryness)

(headscarf)

(hail)

(shake hands)

(old man)

(graft)

Nasal

ncinyane

uNcube

ingcebethu

ngcono

ilinqe

inqola

ingqamu

ingqina

nxa

inxeba

ingxabano

ingxenye

(small)

(a clan name)

(small basket)

(better)

(vulture)

(cart)

(knife)

(hoof)

(when)

(wound)

(quarrel)

(part)

Voiced

gcina

amagcobo

kugcwele

umgqala

isigqili

isigqoko

(keep)

(ointment)

(it is full)

(crossbar)

(slave)

(dress)

isigxingi

gxoza

gxumeka

(calabash)

(dribble)

(transplant)

IV STRESS

The main stress in the word falls on the next to last syllable, the penul­

timate syllable, which is lengthened. If more syllables are added to the

word, the stress will move forward so that it remains on the penultimate

syllable.

e.g. /tomba; haml>ani; hambamni

There are very few exceptions to this rule, and these will be pointed out

as they occur in the lessons.

In a group of words, the stress on individual words is secondary to the

main stress of the whole group,

e.g. Ngiya/ima (I want)

Ngifuna ukuÄomba (I want to go)

Ngifuna ukuhamba /awe (I want to go with you)

V INTONATION

Intonation refers to the way the syllables of the words are spoken: with a

high tone of voice or a low tone of voice. In the main, this has to be

learnt by imitation, but it is important. In some instances the whole

meaning of words may change with a change of tone,

e.g. imizi — kraals (high tone)

imizi — reeds (low tone)

uyafuna — he/she wants (high tone for first two syllables)

uyafuna — you want

(low tone for first two syllables)

There are various shades of tone, but it is sufficient to note whether

the tone is high or low.

VI PRONUNCIATION PRACTICE

Impondo zebhalabhala ezitshileneyo

(The twisted horns of the kudu)

Ngihlangane logogo egaxe iqhele

(I met grandmother wearing a band)

Ngisendleleni ngihlangane lexhegu ligaxe iqhele

(On the way I met an old man wearing a band)

Ixhegu laxoxomela laxamalaza

(The old man stood on tiptoe and with feet astride)

Ngubani owaqaga iqanda eguqile emgwaqweni wakoSikume?

(Who caught the egg when kneeling on the road to Sikume?)

Iqaqa lalizigiqagiqa engqoqwaneni laze laqethuka

(The polecat was rolling in the frost, then fell over backwards)

Iqaqa lalizigiqagiqa laze laqamula umqala

(The polecate was rolling along until it broke its neck)

Lesson 2

The verb

I

THE INFINITIVE

In Ndebele the verb consists of a basic stem, to which various prefixes and

suffixes are attached.

e.g. ‘-sebenza’ is the stem of the verb meaning ‘to work’,

‘-hamba’ is the stem of the verb meaning ‘to go’.

To make the infinitive, that is 'to work’, 'to go’, and so on, the prefix

‘uku-’ is attached to the stem:

ukusebenza — to work

ukuhamba — to go, go away

ukufuna

— to want

Note: verbs in a Ndebele/English dictionary are listed under the initial

letter of their stem, e.g. ‘ukusebenza’ under ‘s’; ‘ukuhamba’ under ‘h’.

The verb stem can be used on its own in one instance only, and that is in

the imperative, when making a command to one person. For example

Hamba! — Go away! This will be dealt with fully in a later lesson.

Apart from this, the verb stem is always used with a prefix of some kind.

II THE PRESENT TENSE

The present tense of the verb, for example, ‘I am going’, ‘I want’, is made by

prefixing a subject concord to a verb stem. For example, the subject

concord

‘Ngi-’ means ‘I’.

Ngifuna — I want

Ngifuna ukuhamba — I want to go

1 Subject concords

1st person singular:

2nd person singular:

3rd person singular:

1st person plural:

2nd person plural:

3rd person plural:

ngiuusiliba-

I

you

he/she

we

you (more than one person)

they

2 Short present tense

,

This is subject concord + verb stem. This short present tense is used only

when something follows the verb stem.

I want to go

e.g. Ngifuna ukuhamba

Ufuna ukuhamba

You want to go

He/She wants to go

Ufuna ukuhamba

Sifuna ukuhamba

We want to go

Lifuna ukuhamba

You want to go

They want to go

Bafuna ukuhamba

Note: intonation in speech distinguishes between ‘u’ — meaning ‘you’

and ‘u-’ meaning ‘he/she’. The first (you) has a low intonation; the second

(he/she) has a higher intonation, and is slightly longer.

3 Long present tense

If nothing follows the verb, a longer form of the present tense must be

used.

To form this, place '-ya- between the subject concord and verb stem.

e.g.

ngiyafuna — I want

uyafuna — you want

uyafuna — he/she wants

siyafuna — we want

liyafuna — you want

bayafuna — they want

Ufuna ukuhamba? Yebo, ngiyafuna.

Do you want to go? Yes, I want to.

The use of the short and long forms of the present tense will be studied

fully in a later lesson.

Vocabulary

ukubona

ukubuya

ukucela

ukudinga

ukudla

ukudlala

ukufuna

ukufunda

ukufundisa

ukugeza

ukugezisa

ukugijima

ukugula

ukuhamba

ukuhlala

ukuhleka

ukukhala

to

to

to

to

to

to

to

to

to

to

to

see

come back

request

seek

eat

play

want

learn

teach

wash (oneself)

wash

(something)

to run

to be ill

to go (away)

to stay; sit down

to laugh

to cry

ukukhangela

ukukhuluma

ukuUma

ukunatha

ukungena

ukupheka

ukuphuma

ukusebenza

ukusiza

ukuthanda

ukuthanyela

ukuthatha

ukuthenga

ukuthengisa

ukuthula

ukuthunga

ukutshaya

to look at

to speak

to plough

to drink

to go in/come in

to cook

to go out/come out

to work

to help

to like, love

to sweep

to take

to buy

to sell

to be quiet

to sew

to hit, beat

Lesson 3

The noun:

UM/ABA class

1 Introduction

In Ndebele the noun has two parts: a stem, and a prefix.

e.g. The word meaning ‘boy’ : umfana;

the stem is ‘-fana’ : the prefix is ‘um-’.

The prefix of the noun changes according to whether it is singular or

plural, but the stem remains the same,

e.g. Singular : «/nfana — boy

Plural : abafana — boys

There are a number of different prefixes for the noun stems:

e.g. stone : ilitshe (iVi-tshe)

stones : amatshe (ama-tshe)

dog : inja (««-ja)

dogs : inzinja (/r/n-ja)

Each of these nouns belongs to a different noun class, and you will learn

the eight different noun classes one by one.

It is essential to learn the noun prefixes thoroughly, for it is on them

that the whole structure of the language depends. The following illustration

will help you to see this:

The little boy who is running is thin.

C/wfana o/micinyane agijimayo ucakile.

The little dog which is running is thin.

/nja encinyane egijimayo /cakile.

2 The article

In English nouns are usually preceded by an article, ‘a’ or ‘the’. There

is no article in Ndebele; the noun stands alone,

e.g. ‘umfana’ means ‘a boy’ or ‘the boy’.

‘abafana’ means ‘boys’ or ‘the boys’.

3 The noon: UM/ABA class

The singular noun has prefix UM- or UMU-. The plural noun has prefix

ABA-.

e.g. «mfana — boy

«¿ofana —

boys

M/wntwana — child ahantwana — children

The longer prefix UMU- is used before a noun stem of only one syllable:

e.g. ttwantu — person

aftantu — people

If the noun stem begins with a vowel, the plural prefix wUl be just AB-.

e.g. Mwakhi — builder

aAakhi — builders

Mwelusi — herdsman alielusi — herdsmen

Note: in the dictionary nouns are listed under the initial letter of their

stem. For example, ‘umfana’ under ‘f’, ‘umuntu’ under ‘n’, ‘umakhi’

under ‘a’.

8

4 Subject concords

The noun may be the subject of the verb, for example: 'The boy wants to

work.’ In Ndebele the verb stem needs a subject concord prefixed to it

always, even when there is a noun subject.

e.g. Umfana «fuña ukusebenza — The boy wants to work

The subject concord comes from the noun prefix:

Prefix UM-/UMU- gives concord U-:

e.g. £/mfana «fuña ukusebenza — The boy wants to work

Umuntu. «yasebenza — The person is working

Prefix ABA- gives concord BA-;

e.g. .diáfana iafuna ukusebenza — The boys want to work

AbaxAxx iayasebenza — The people are working

VOCABULARY

All the nouns in this class are persons.

abakhi

builders

umakhi

builder

umbazi

ababazi

carpenters

carpenter

herdsmen, herd

herdsman, herd abelusi

umelusi

boys

boy

abafana

boys

umfana

boy

abafazi

wives

umfazi*

wife

teachers, ministers

umfundisi

teacher, minister abafundisi

abalimi

farmers

umlimi

farmer

aban tu

persons, people

umuntu

person

children

abantwana

umntwana

child

abapheki

cooks

umpheki

cOok

drivers

abatshayeli

umtshayeli

driver

abazali

parents

umzali

parent

* Only use ‘umfazi’ if you really mean ‘wife’; it is not good to use

this noun as a general term for ‘woman’.

Lesson 4

The noun: U/O class

1 Prefixes

The singular noun has prefix U-.

The plural noun has prefix

0-.

e.g. «baba — my/our father

umama — my/our mother

obaba

omama

our fathers

our mothers

2 Subject concords

This class of noun is closely related to the UM/ABA class, being also a

class of personal nouns, and it has the same concords.

Singular: U- : Umama uyapheka — Mother is cooking

Plural:

B A -: Omama iayapheka — Our mothers are cooking

3 Nouns for family relationships

Most of the nouns in this class are in this category, and there are three

nouns each for mother, father, and grandfather, according to the relation­

ship.

ubaba

— my/our father

obaba

— our fathers

uyihlo

— your father

oyihlo

— your fathers

uyise

— his/her/their father oyise

— their fathers

ubabamkhulu — my/our

obabamkhulu — our grand­

grandfather

fathers

uyihlomkhulu — your grand­

oyihlomkhulu — your grand­

father

fathers

uyisemkhulu — his/her/their

oyisemkhulu — their

grandfather

grandfathers

umama

— my/our mother

omama

— our mothers

unyoko

— your mother

onyoko

— your mothers

unina

— his/her/their

onina

— their mothers

mother

For grandmother, one can proceed in1 the same way as for grandfather.

using ‘umama’ and adding ‘mkhulu’ (big), for example, ‘umamamkhulu’,

shortened to ‘umakhulu’. However, in Ndebele the more common word

for grandmother is ‘ugogo/ogogo’ just the one noun.

There are a few nouns for animals and insects in this class:

e.g. ubabhemi —

— donkey

donkey

obabhemi — donkeys

umangoye — cat

omangoye — cats

Umangoye «yahamba — The cat is going

Omangoye hnyahamba — The cats are going

¡Vote: ‘umama’ and ‘ubaba’ may be used to mean ‘a mother’ and ‘a

father’ in a general sense, and also ‘a woman’ or ‘a man’,

e.g. Omama bafuna ukupheka — The women (ladies) want to cook

Obaba bafuna ukuphumula— The men (gentlemen) want to rest

10

4 Names

Names of people belong in this class, and must have the prefixes U- or 0-.

a) The first name (ibizo), given to a child after birth:

e.g. t/Sipho uyadlala

— Sipho is playing

Ngifuna «Sipho

— I want Sipho.

Traditionally, the first name is not used after childhood when addressing a

person, but only for identification purposes.

b) The clan name or surname (isibongo), which all children take from

the father.

e.g. i/Khumalo uyahamba — Khumalo is going away

Ngifuna «Khumalo

— I

OKhumalo bayahamba — The Khumalos are going away

Ngithanda oKhumalo — I like the Khumalos

A person will normally be addressed by his clan name. Women also are

addressed by their clan name, that is, the clan name of their father, which

they retain even when married, usually with the prefix ‘Ma-’ (from'umama’).

e.g. t/MaKhumalo uyahamba — MaKhumalo is going away

Ngifuna «MaKhumalo

— I want MaKhumalo

c) Use of an ancestral name (isitemo). This is usually the grandfather's

first name, which may be taken and used by the grandson as another

surname, although he still retains his ‘isibongo’ as well.

Through experience you will learn which are the clan names, as they

are limited in number.

11

want Khu

Lesson 5

The object of the verb

1 The object concord

a) You have learnt the concords for the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd persons as

subject of the verb:

e.g. /z^/yathanda — /like

When used as the object of the verb, the concord is placed immediately

before the verb stem; this rule for the position of the object concord never

changes.

e.g. Uya/z^/'thanda — He likes me

Uyay/thanda — He likes us

The object concord is the same as the subject concord, except where it is a

single vowel:

2nd person singular (you) : u becomes ku

3rd person singular (he/she) : u becomes m

Subject Concord

Object concord

ngi-ngie.g. Uyaw^ithanda — He likes me

UyaAuthanda — He likes you

u-kuNgiyamthanda — I like him

-muUyas/thanda — He likes us

si-si-liNgiya/ithanda — I like you

liNgiyaiathanda — I like them

ba-baThe object concord may also be put with an infinitive:

e.g. Ngifuna ukuAabona — I want to see them

Ngithanda ukuA:«siza — I like to help you

Ufuna uku«?/tshaya — You want to hit me

b) Concords for nouns

Each noun has its object concord in the same way as it has its subject

concord. For the UM/ABA, U/O nouns, the concords are the same as for

the third person,

Ngiya/Msiza

e.g. Ngiyasiza umama

I am helping my mother

I am helping her

Ngiyamtshaya

Ngjyatshaya umangoye

I am hitting it

I am hitting a cat

Bayatshaya abantwana

Bayaifltshaya

They are hitting them

They are hitting some children

Baya/zatshaya

Bayatshaya obabhemi

They are hitting some donkeys They are hitting them

2 Noun object of tbe verb

The object of the verb may be a noun:

e.g. Ubaba uyatshaya umfana — Father is hitting a boy

The object concord may be used together with the noun: i

12

e.g. Ubaba uyamtshaya umfana — Father is hitting the boy

Bayaftatshaya abantwana — They are hitting the children

In these last two examples you are talking about a particular boy (and

particular children) to whom you have previously referred, and therefore

the object concord is used.

You may make a general statement:

e.g. Ugogo uthanda ukukhangela abantwana — Grandmother likes to

watch the children

But if you have referred to particular children and you mean those, you

will use the object concord:

e.g. Ugogo uthanda uku^ukhangela abantwana

Similarly compare;

Ngifuna ukubona umama — I want to see my mother

Ngifuna ukuwbona umama — I want to see the woman

Note that the noun object may be placed before the subject sometimes, and

it will then be used with the object concord,

e.g. Ugogo ngiyawbona — I see the grandmother

Umfana ubaba uyamtshaya — Father is beating the boy

13

Lesson 6

Requests and commands; the imperative verb

1 The imperative verb

This form of the verb is used for requests or commands;

e.g. ‘Look!’

‘Come here!’

Singular: when speaking to one person, use the stem of the verb only,

e.g. Khangela! — Look!

Sebenza! — Work!

Plural:

when speaking to more than one person, add ‘-ni’ to the

verb stem.

e.g. Khangelan/! — Look!

Sebenzan;! — Work!

This is the form most common these days. There is another form of the

plural imperative, where ‘-nini’ is added to the verb stem,

e.g. Fundan/w! — Learn!

Dingan/w! — Search!

When this is used it seems to be extra polite, and may also be used for

extra politeness when addressing only one person.

Learn the imperative form of the verb ‘ukuza’, to come — which is

irregular:

Singular: W oza!— Come!

Plural: Wozani!

Do not at this stage try to use object concords in front of imperative

verbs, as the form of the verb changes when one does this.

The exception to this is ‘ngi’, which you can easily use with a singular

imperative:

e.g. Ngikhangela! — Look at me!

Ngisiza! — Help me!

Learn how to use these three verbs: ukunika — to give (to)

ukulethela — to bring to

ukuyekela — to leave off, stop

doing

e.g. Nginika! — Give (to) me!

Ngilethela! — Bring (to) me!

Yekela! — Stop it!

Yekela ukukhala! — Stop crying!

2 How to address people

When addressing someone, always drop the initial vowel of the noun used,

e.g. umama becomes

mama!

Khangela, mama!—Look, mother!

uThandiwe becomes Thandiwe! Ngisiza, Thandiwe!—^Help me,

Thandiwe!

umfana becomes mfana!

Woza, mfana!—Come, boy!

abafana becomes bafana!

Wozani, bafana!—Come, boys!

14

Exception: When using a plural noun with prefix 0-, for example

omama, the initial vowel is not dropped, as this would cause confusion

with the singular form. Instead, the letter ‘b’ is prefixed to the noun:

e.g. Khangelani, fiomama! — Look, mothers!

Wozani, fiobaba ! — Come, fathers !

All other nouns in the language drop the initial vowel when used as a form

of address.

Note: the polite way of addressing adults is to use ‘mama/bomama’ for

women, and ‘baba/bobaba’ for men.

Ngenani bobaba!

e.g. Ngena baba!

Woza mama!

Wozani bomama!

15

Lesson 7

Interjections and the question

1 Interjections

These are the common ones :

— Yes

Yebo/Ye

— Certainly (‘ke’ is attached to words to give added

Yebo-ke

emphasis)

Ehe

— Yes (with approval) Yes, that’s it

Ayi/Atshi

— No (occasionally ‘hayi/hatshi’)

Atshi bo

—■Certainly not

A’a

— No (with disapproval)

Various exclamations of surprise, disapproving or not, depending on

the tone of voice:

A’!

Hawu!

Bakithi!

Bantu!

Dadewethu!

X! — Expresses annoyance.

C! — Expresses pity, sympathy, scorn, disgust, or disapproval.

Mayel/Mamo! — Expresses pain, dismay, grief, on behalf of oneself or

someone else.

Phepha!— Usually translated ‘Sorry!’, but it is not an apology.

It would be used, for example, if the other person tripped, or knocked

himself. (It comes from the verb ‘ukuphepha’ meaning ‘to escape from

danger.’)

Uxplo! — This is a noun meaning ‘pardon’, and is used to excuse

oneself: ‘Excuse me!’ (The verb ‘ukuxolisa’ may also be used, e.g.

ngiyaxolisa — I apologise.)

Thanking: It would be appropriate to mention this here.

The verb ‘ukubonga’ (to thank, be thankful) may be used with or without

an object concord. For example: Ngiyabonga/Ngiyakubonga mama —

Thank you, mother. If you are giving thanks for something past, for

example at the end of a meeting, for a gift or service previously received,

and so on, use the form: Ngibongile/Sibongile.

The traditional form of thanking is to use the clan name of the person

being thanked, with the prefix ‘e-’:

e.g. ENdlovu!

— Thank you, Ndlovu!

EKhumalo! — Thank you, Khumalo!

2 The question

a) NA? To make a question, simply place ‘na’ at the end of the sentence,

e.g. Umama uyahamba — Mother is going away

Umama uyahamba na? — Is mother going away?

Abafana bathanda ukugijima kakhulu — Boys like to run fast

16

Abafana bathanda ukugijima kakhulu na ? — Do boys like to run

fast?

b) YINI? This really means, ‘What is it?’, and may be used on its own,

signifying: ‘What do you want ?’ or ‘What’s the matter?’

It may also be used to make a question in the same way as ‘na’, but it may

be a little more emphatic,

e.g. Uyamthanda — You love him

Uyamthanda yini? — Do you love him?/Do you really love him?

c) ANGITHl? This means literally, ‘Do I not say?’, and is used when

seeking the agreement of the person addressed.

e.g. Abafana bayasebenza kuhle, angithi! — The boys are working well,

aren’t they?

Ufuna ukufunda, angithi ? — You want to learn, don’t you ?

Angithi, ufuna ukufunda? — You want to learn, don’t you?

When answering in agreement, ‘sibili’ is often used, and it means ‘indeed’,

e.g. Abantwana bathanda ukudla — Ye, sibili!

Children like eating — Yes, indeed!

17

Lesson 8

The greetings

1 Traditionally, when a person visits a village, he stands at the gate

and calls out ‘Ekuhle’. When someone answers ‘Yebo’, he then approaches

the dwellings, sits right down on the ground, and waits to be greeted

by those in the village.

2 This is the basic form of greeting, used when addressing more than one

person, or sometimes only one person. The Ndebele is partly corrupt,

but a rough translation is given:

A : SaUbonani — We see you

B: Yebo, salibonani — Yes, we see you

A : Linjani ? — How are you ?

B: Sikhona, singabuza lina? — We are present, may we ask you?

OR Sikhona, singatsho lina?

A: Sikhona — We are present

Note: in the old days the plural form of the greeting, given above, was

used only when addressing more than one person. However, the Shona

custom of using a plural form when addressing one person, to show

respect, has influenced the Ndebele people. Some people now use the

plural form when addressing one person.

3 The singular form of the greeting, used when addressing one person:

A : Sakubona

B: Yebo, sakubona

A: Kunjani?

B: Sikhona, singabuza lina? OR Sikhona, singatsho lina?

A: Sikhona

When addressing a child or a young person, an older person will contract

‘Sakubona’ and say: ‘Sabona mntanami’ (my child).

4 The morning greeting, used to greet someone you have seen the day

before, or whom you see often. The verb ‘ukuvuka’ (to wake up, get up) is

used:

A: Livukile? — Have you woken?

B : Sivukile, singatsho lina/singabuza lina ? — We have woken, and you ?

A : Sivukile — We have woken

Singular form: Uvukile?Ngivukile

Alternative form: Uvuke/Livuke njani ?—How did you wake ?

5 The evening greeting, used to greet someone you have already greeted

that day or whom you see often. The verb ‘ukutshona’ (to go down,

set — of the sun) is used:

A: Litshonile?

B: Sitshonile, singatsho lina/singabuza lina?

A: Sitshonile

18

Singular form: Utshonile ? Ngitshonile

Alternative form: Utshone/Litshone njani?

6 Goodbye. One says either ‘stay well’ or ‘go well’, whichever is appro­

priate, using the verbs ‘ukusala’ (to remain) and ‘ukuhamba’ (to go):

Singular: Hamba kuhle — Go well

Sala kuhle — Stay well

Plural:

Hambani kuhle — Go well

Salani kuhle — Stay well

Alternative form: Singular: Uhambe kuhle OR Usale kuhle

Plural:

Lihambe kuhle OR Lisale kuhle

Someone leaving at midday may say: Kusemini — It is midday

7 Goodnight. Use the verb ‘ukulala’ (to go to sleep):

If the person is already in the place where he will sleep, say:

Singular: Lala kuhle — Sleep well

OR Ulale

Plural: Lalani kuhle

OR

Lilale

If he has to go off to his home, say:

Singular: Uyelala — Go and sleep

Plural:

Liyelala

Someone leaving in the evening may say: Kuhlwile — It is dark

8 Asking after one’s health. Use the adverb ‘njani’, meaning ‘how’, and

put the appropriate subject concord before it:

e.g. Plural:

¿/njani? How are you

Singular: i/njani? How are you? OR Kunjani? (as in the

,

greeting)

Unjani umntwana? — How is the child?

Banjani abantwana? — How are the children?

Banjani ekhaya?

— How are they at home?

In answer, one may either use the adverb ‘khona’ (present):

e.g. 5/khona — We are present

i7khona — He/She is present

Bakhona — They are present

OR one may use a verb, ‘ukuphila’, meaning ‘to live, be well’:

e.g. Siyaphila — We are well

Uyaphila — He/She is well

Bayaphila — They are well

Note: umkami — my wife OR my husband

umkakho — your wife/husband

umkakhe — his wife/her husband

e.g. Unjani umkakho? — How is your wife/husband?

9 One may send greetings to others in this way:

e.g. Ubabone ekhaya — Greet the people at home (See them at home)

Ubabone abantwana — Greet the children

OR use the verb ‘ukubingelela’ (to greet),

e.g. Ubabingelele abantwana — Greet the children

Note that the basic greeting is usually accompanied by a hand shake.

19

Lesson 9

Interrogative adverbs

1 Learn these;

ngaphi? — where?

nini? — when?

njani? — how?

-ni? — what?

2 Use of short present tense

These adverbs may be used with any verb, and the verb will be in the

short form, without 'ya'. The interrogative adverb is normally placed

immediately after the verb.

e.g. Abantu basebenza ngaphi? — Where do the people work?

Basebenza ngaphi khathesi? — Where are they working now?

Unyoko upheka nini? •— When does your mother cook?

Uthunga njani ? — How do you sew ?

‘What ?’ is translated by the suffix ‘-ni’, which is attached to the verb stem,

e.g. Ufuna umama — You want mother

Ufunani? — What do you want?

Bayafunda — They are learning

Bafundani ? — What are they learning ?

Bafuna ukudla — They want to eat

Bafuna ukudlani? — What do they want to eat?

Note that in speech the stress moves so that it will still be on the penulti­

mate syllable: u/«na .. .ufunani?

3 a) Use of the verb ‘ukuya’ (to go to. . .)

This verb is commonly used with ‘ngaphi’.

e.g. Uya ngaphi ? — Where are you going ?

Baya ngaphi ? — Where are they going ?

‘Ukuya’ means ‘to go t o .. . ’ somewhere, and as such is never used without

either ‘ngaphi ?’ or a stated destination,

e.g. Ngiya ekhaya — I am going (to) home

Ngiya koBulawayo — la m going to Bulawayo

Present tense:

ngiya siya

uya liya

uya baya

The verb ‘ukuhamba’ does not convey the idea of a destination, but

merely movement itself, and may be translated ‘go away", or ‘move along’,

or ‘walk’.

e.g. Abantwana bayahamba — The children are going away/walking

along

h) Another interrogative is ‘bani?’, meaning ‘whom?’

e.g. Udinga bani ? — Whom do you want ? (Whom are you looking for ?)

Abantwana bathanda bani? —^ Whom do the children love?

This actually comes from a noun, ‘ubani’, plural ‘obani’, meaning ‘who?’

which you will meet again later.

20

4 Use of adverbs without a verb

In English we may use the verb ‘to be' and say for example: ‘Where is

mother ?’, ‘How are the children ?'

In such instances there is no verb used in Ndebele; the required concord

is merely placed before the adverb,

e.g. Umama «ngaphi OR Ungaphi «mama ? — Where is mother ?

/46antwana Zxinjani? OR innjani oftantwana? — How are the

children ?

21

Lesson 10

Present tense: use of the short and long forms

One needs to use both the short and long forms of the present tense in

Ndebele, and there are some guidelines to be laid down as to when each

form may be used. It would be difficult to work out strict rules to cover

every use of the present tense in everyday spoken Ndebele, but you will

not go far wrong if you follow these guidelines.

1 The long form of the present tense

This form uses ‘ya’ e.g. Ngiyafuna — I want

a) The long form is used when nothing else follows the verb in the

clause or sentence.

e.g. Uthanda ukudlala na? Ye, ngiyathanda

Do you like playing? Yes, I like to

Ufuna ukunatha itiye na? Ye, ngiyafuna

Do you want to drink some tea? Yes, I do

Abantwana bayohamba — The children are going

Note: the interrogative ‘na?' is not counted as an extension of the verb;

the long form must be used in such sentences as this:

e.g. Abantwana bayahamba na? — Are the children going?

Uyafuna na? — Do you want to?

b) The long form is used when an object concord is used with the verb,

e.g. Uyambona umntwana na? — Do you see the child?

Uyabafuna abantwana na? — Do you want the children?

Abantwana bayabathanda omangoye — The children love the cats

c) The tong form is used for a verb of action, when the action is going

on at the present time.

e.g. Umntwana uyadlala lapha — The child is playing here

Ubaba uyatshaya umfana — Father is hitting a boy

Abantu bayanatha itiye — The people are drinking tea

2 The short form of the present tense

This form does not have ‘ya’.

a) The short form is used before an infinitive

e.g. Ngifuna ukuhamba — I want to go

Ngithanda ukupheka — I like cooking

Ngifunda ukupheka -— I am learning to cook

Ngizama ukufunda — I am trying to learn

But if one is referring to something actually going on at the present

time, the long form will be used,

e.g. Ngiyafunda ukupheka — I am learning to cook (right now)

Siyathaba ukulibona — We are happy to see you

b) The short form is used with an interrogative adverb.

22

e.g. Uhlala ngaphi? — Where do you live?

Umama upheka nini? — When does mother cook?

Upheka lokhu njani ? — How do you cook this ?

Umfana usebenza ngaphi khathesi ? — Where is the boy working

now?

c) The short form is used for a verb which does not involve action

(provided something follows the verb and there is no object concord).

e.g. Ngibona umntwana — I see a child

Ngifuna itiye — I want some tea

Ngicela imali — I request some money

Ngidinga uDube — I want (am looking for) Dube

d) The short form is used for a verb of action when there is no present

action, that is, for a statement of fact, or a general question.

e.g. Abantwana banatha itiye na ? Ye, abantwana banatha itiye

Do children drink tea? Yes, children drink tea

Lidíala lapha na? Ye, sidlala lapha

Do you play here? Yes, we play here

23

Lesson 11

The negative verb; present tense

Formation

There is only one form of the negative present tense, based on the subject

concord and the verb stem; for example, ngibona (I see).

Place the negative KA- before the subject concord, and change the

final vowel of the verb stem to ‘-i’: for example, Arnngibon; — I don’t see.

Negative present tense of ukupheka — to cook:

Kangipheki

I don’t cook/I am not cooking

Kawupheki

You don’t cook/You are not cooking

Umama kapheki

Mother doesn’t cook/Mother isn’t cooking

Kasipheki

We don’t cook/We are not cooking

You don’t cook/You are not cooking

Kalipheki

Our mothers don’t cook/Our mothers are not

Omama kabapheki

cooking

Note:

a) If two vowels come next to each other in Ndebele, one of them may

be dropped, or they may be spoken with a semivowel, ‘w’ or ‘y’, in be­

tween.

Second person singular: pronounce a ‘w’ between ‘ka’ and ‘u’, for

example, kawupheki.

Third person singular: the negative form is just ‘ka-’, for example,

umama kapheki.

b) The negative KA-may be shortened to A -: for example, Angipheki,

Awupheki, and so on.

c) Learn these two negative verbs which are different:

Angazi — I don’t know; Angizwa — I don’t hear, I don’t understand

d) Indefinite object

If there is an indefinite noun object, and no object concord is used, the

initial vowel of the noun object may be dropped:

e.g. Kangiboni muntu (umuntu) — I don’t see anyone

Kangifuni mali (imali) — I don’t want any money

24

Lesson 12

The noun: UM/IMI class

1 Prefixes

The singular noun has prefix UM- or UMU-.

The plural noun has prefix IMI-.

e.g. «wfula

— river

/m/fula — rivers

ttwlilo

— fire

//M/Ulo

— fires

The longer prefix UMU- is used before a noun stem of only one syllable,

e.g. umuzi

— kraal

imiz\

— kraals

Note that all the nouns of this class are impersonal; so in this way the

singular nouns can be distinguished from the singular nouns of the

UM/ABA class, which are personal.

In speech, when the plural prefix IMI- comes before noun stems of more

than one syllable, the second ‘i’ is hardly pronounced, so that ‘imifula’

sounds like ‘imfula’ ‘imililo’ like ‘imlilo’, and so on.

2 Concords

a) Subject concords: prefix UM/UMU- gives concord U— The river is flowing

e.g. Umfula Myageleza

t/yageleza

— It is flowing

— The fire is burning

Umlilo «yavutha

— It is burning

i/yavutha

Prefix IMI- gives concord 1— The rivers are flowing

e.g. Imifula /yageleza

—■ They are flowing

/yageleza

— The fires are burning

Imililo /yavutha

—■ They are burning

/yavutha

b) Object concords: These are the same as the subject concords, but

as they are vowels, it is necessary to put a semivowel between them and the

preceding vowel ‘a’; so put ‘w’ with ‘u’, ‘y’ with ‘i’.

Singular: -WUe.g. Ngiyawttbona umfula — I see the river

Ngiyawabona — I see it

Ngiyawttbona umlilo — I see the fire

Ngiyawnbona — I see it

Plural: -YIe.g. Ngiyay/bona imifula — I see the rivers

Ngiyay/bona — I see them

Ngiyay/bona imililo — I see the fires

Ngiyay/bona — I see them

3 The negative

When putting the negative ‘ka’ before the subject concords, it is necessary

once again to keep the vowel apart with ‘w’ and ‘y’e.g. Umfula kanoigelezi — The river is not flowing

25

Umlilo kavvuvuthi — The fire is not burning

Imifula kajdgelezi — The rivers are not flowing

Imililo kaj'ivuthi — The fires are not burning

VOCABULARY

Prefix UMumbhida

umfanekiso

umfula

umganu

umgwaqo

umlilo

umlomo

umsebenzi

umthanyelo

umoya (stem:

-moya)

umzimba

Prefix UMUumunwe

umuthi

umuzi

umumbu

26

vegetable

picture

river

plate; dish

road

fire

mouth

work; job

broom, brush

wind, spirit

Prefix IM limibhida

imifanekiso

imifula

imiganu

imigwaqo

imililo

imilomo

imisebenzi

imithanyelo ,

imimoya

vegetables

pictures

rivers

plates; dishes

roads

fires

mouths

jobs

brooms

winds, spirits

body

imizimba

bodies

fingers

finger

iminwe

medicines

medicine

imithi

kraals, villages

kraal, village

imizi

maize; mealie; some mealies (has no plural)

Lesson 13

The noun:

ILI/AMA class

1 Prefixes

The singular noun has prefix ILI- or I-.

The plural noun has prefix AMA-.

The prefix ILl- is used before noun stems of one syllable,

e.g. iV/tshe — stone

amatshe

— stones

///zwe

— country

amazwe

— countries

The shorter prefix 1- is used before noun stems of more than one syllable

(these constitute the majority),

e.g. /hloka — axe

amahloka — axes

ijaha

— youth

awajaha

— youths

2 Concords

a) Subject concords Prefix ILI- gives concord LI-.

e.g. Ilitshe//ngaphi?

— Where is the stone?

¿ingaphi?

— Where is it?

Ijaha //yasebenza

— The youth is working

L/yasebenza

— He is working

Prefix AM A- gives concord A-.

- Where are the stones ?

Amatshe nngaphi ?

- Where are they?

.4ngaphi?

- The youths are working

Amajaha ayasebenza

y4yasebenza

~ They are working

b) Object concords

These are the same as the subject concords, but concord A-, being a

vowel, is used with *w’.

Singular; -LIe.g. Ngiya/ibona ilitshe — I see the stone

Ngiya/Zbona — I see it

Ngiya/ibona ijaha — I see the youth

Ngiya/ibona — I see him

Plural: -WAe.g. Ngiyawabona amatshe — I see the stones

Ngiyatvabona — I see them

Ngiyawabona amajaha — I see the youths

Ngiyatvabona — I see them

3 The negative

e.g. Ijaha kalisebenzi -—The youth is not working

Ilitshe kaliboni — A stone doesn’t see

When placing ‘ka’ before concord A-, insert ‘w’ to keep the vowels apart,

e.g. Amajaha katvasebenzi — The youths are not working

Amatshe kawaboni — Stones don't see

But note that in speech one may combine these two ‘a’s’, and the concord

will be a lengthened ‘ka’. For example, Amajaha Arasebenzi.

27

VOCABULARY

Prefix ILIilitshe

ilizwe

ilizwi

ilihlo

stone

country

word; message; voice

eye

Irregular form.

Prefix /igwayi

ihloka

ijaha

ikhabe

ikhanda

ikhaya

ikhuba

ilambazi

ilanga

ilembu

iqanda

ithanga

itshwayi

ixhegu

izulu

tobacco, cigarettes

axe

youth; unmarried man

water melon

head

home

plough; hoe

soft mealie porridge

sun; day

cloth, material

egg

pumpkin

salt

old man

rain; sky

amaliloka

amajaha

amakhabe

amakhanda

amakhaya

amakhuba

amalanga

amalembu

amaqanda

amathanga

Irregular form

The weather

28

llanga liyatshisa —

OR Kuyatshisa —

Kuyaqanda—

Ngiyagodola —

Izulu liyana —

Prefix AMAamatshe

amazwe

amazwi

amehio

amaxhegu

amazulu

amakhaza (no singular)

cold weather

ainanga (no singular) —

lie, lies

amanzi (no singular) —

water

ameva (sing, rarely used)

thom/thoms

It is hot (The sun is hot)

It is hot

It is cold

I am cold

It is raining

Lesson 14

The noun: ISI/IZI class

1 Prefixes

The singular noun has prefix ISI-.

The plural noun has prefix IZI-.

e.g. wmkwa

— loaf of bread

iz/nkwa

loaves

»/hlahla — tree

/zihlahla

trees

If the noun stem begins with a vowel, the second ‘i’ of the prefix is dropped,

e.g. isalukazi — old woman

/zalukazi — old women

/joni

— evil doer

izoni

— evil doers

2 Concords

a) Subject concords: Prefix ISI- gives concord SI-.

e.g. Isinkwa j/ngaphi? — Where is the loaf?

5/ngaphi? — Where is it?

Isalukazi s/yagula — The old woman is ill

5iyagula — She is ill

Prefix IZI- gives concord ZI-.

e.g. Izinkwa z/ngaphi? — Where are the loaves?

Z/ngaphi? — Where are they?

Izalukazi z/yagula — The old women are ill

Z/yagula — They are ill

b) Object concords

Singul^ -SI"

e.g. Ngiyaribona isinkwa — I see the loaf

Ngiyaribona — I see it

Ngiyastbona isalukazi — I see the old woman

Ngiyaj/bona — I see her

Plural: -ZIe.g. Ngiyazibona izinkwa — I see the loaves

Ngiyaz/bona — I see them

Ngiyaz/bona izalukazi — I see the old women

Ngiyaz/bona — I see them

The Negative

e.g. Isinkwa kasitshisi — The loaf is not hot

Isalukazi kasiguli — The old woman is not ill

Izinkwa kazitshisi — The loaves are not hot

Izalukazi kaziguli — The old women are not ill

29

VOCABULARY

Prefix ISIisalukazi

isandia

isanuse

isicathulo

isigqoko

isigelo

isigulane

isihambi

isihlahla

isihlalo

isikhathi

isikhwama

isinkwa

isipho

isiphofu

isisebenzi

isisu

isitsha

isitshebo

isitshwala

isivalo

old woman

hand

witch doctor

shoe

dress, garment

pair of scissors

patient (medical)

traveller

tree

seat, chair

time

purse, handbag; pocket

loaf of bread

gift

blind person

worker

stomach

vessel, container (basket, bowl)

relish

stiff porridge

door

Prefix IZlizalukazi

izandta

izanuse

izicathulo

izigqoko

izigelo

izigulane

izihambi

izihlahia

izihlalo

izikhathi

izikhwama

izinkwa

izipho

iziphofu

izisebenzi

izisu

izitsha

izivalo

To open or close the door, use umnyango (um/imi) ■ the doorway.

e.g. Vala umnyango — Close the door

Vula umnyango — Open the door

The time: Yisikhathi bani? — What is the time?

30

Lesson 15

The noun: IN/IZEM class

1 Prefixes

The singular noun has prefix IN- or IM-.

The plural noun has prefix IZIN- or IZIM-.

e.g. /nja — dog

tz/>/ja — dogs

wduna — chief

?z/«duna — chiefs

i/nvu — sheep

izinmx — sheep

iwbuzi — goat

/z/mbuzi — goats

The prefix IM/IZIM is used with noun stems begitming with consonants

b,p,f,v.

e.g. imhuzi

impuphu (mealie meal)

im/e (sweet cane)

imvu

Before all other consonants, the prefix IN/IZIN is used.

2 Concords

fl) Subject concords: Prefix IN-/IM- gives concord I-.

e.g. Ipja lyadla — The dog is eating

/yadla — It is eating

Imbuzi /yadla — The goat is eating

/yadla — It is eating

Prefix IZIN-/IZIM-• gives concord ZI-.

e.g. Izinja z/yadla — The dogs are eating

Z/yadla — They are eating

Izimbuzi z/yadla — The goats are eating

Z/yadla — They are eating

Note: the plural prefix IZIN-/IZIM- is very often shortened to IN-/IMprovided the plural concord ZI- (or some other part of speech, like an

adjective) is used, and shows that the noun is plural,

e.g. Imbvtii ziyadla — The goats are eating

7/iduna z/yafika — The chiefs are arriving

In speech the vowel sound will be longer in the plural IN-/IM- than it is

in the singular. Do not shorten the plural prefix of nouns with one syllable

steins.

e.g. Always: /zi//ja ziyadla

/zi/nvu ziyadla

b) Object concords: The vowel I- is used with a “y’.

Singular: -YIe.g. Ngiyay/bona inja — I see the dog

Ngiyay/bona — I see it

Ngiyay/bona imbuzi — I see the goat

Ngiyay/bona — I see it

Plural: -ZIe.g. Ngiyaz/bona izinja — I see the dogs

31

Ngiyazibona — I see them

Ngiyaz/bona (iz)imbuzi — I see the goats

Ngiyaz/bona — I see them

3 The negative

Again, use ‘y’ with concord I-.

e.g. Inja kayidli — The dog is not eating

Imbuzi kayidli — The goat is not eating

Izinja kazidli — The dogs are not eating

T

(Iz)imbuzi kazidli

“ he goats are not eating

VOCABULARY

Prefix INindlu

inja

indawo

indlebe

indlela

induku

induna

ingalo

ingqamu

ingubo

inkomo

inkukhu

intaba

intombi

inyama

inyanga

inyoka

inyoni

hut, house; room

dog

place

ear

path, way

club (knobkerrie)

chief

arm

knife

blanket

one of the cattle

domestic fowl

hill, mountain

girl (teenage); spinster

meat

moon, month; doctor (herbalist)

snake

bird

izindlu

izinja

(iz)indawo

(iz)indlebe

(iz)indlela

(iz)induku

(iz)induna

(iz)ingalo

(iz)ingqamu

(iz)ingubo

(iz)inkomo

(iz)inkukhu

(iz)intaba

(iz)intombi

(iz)inyanga

(iz)inyoka

(iz)inyoni

Prefix IMimfe

sweet cane

imvu

izimVu

sheep

imbiza

pot, pan

(iz)imbiza

(iz)imbuzi

imbuzi

goat

(iz)impahla

impahla

goods, possessions, luggage

impuphu

mealie meal

Note: there are some nouns which have a singular form with prefi

(concord I-), and a plural form with prefix AMA- (concord A-).

e.g. indoda

— man, married man

— men

amadoda

— girl (not yet marriageable)

inkazana

amankazana

— girls

intombazana

— girl (not yet marriageable)

amantombazana — girls

insimu

— field

amasimu

— fields

32

Lesson 16

The noun:

ULU/IZIN class

1 Prefixes

The singular noun has prefix ULU- or U-.

The plural noun has prefix IZIN- or IZIM-.

The prefix ULU- is used before noun stems of one syllable.

e.g. u/«thi — stick

izinii — sticks

u/wtho — thing

izinXo — things

The shorter prefix U- is used before noun stems of more than one syllable

(these constitute the majority).

e.g. ugwalo — book, letter

(iz)ingwalo — letters, books

«phondo — horn

(/z)i>wpondo — horns

Plural:

a) Note that the plural prefix IZIN-/IZIM- is usually shortened to

IN-/IM- before noun stems of more than one syllable, as there is no

possibility of confusion with the singular prefix ULU-/U-; noun stems of

one syllable have the full prefix 1Z1N-/1Z1M-.

e.g. /ngwalo

impondo

But: izinti

izinto

b) The plural prefix (IZ)IM- is used before noun stems beginning with

consonants b,p,f,v.

e.g. ubhalu

— cave

(/z)//nbalu — caves

uphondo — horn

(iz)/»ipondo — horns

ufudu — tortoise

(/z)//wfudu — tortoises

Mvava — splinter

(iz)//wvava — splinters

Before all other consonants the plural prefix is (IZ)IN-.

c) After the ‘n’ or ‘m’ of this prefix consonants are not pronounced with

aspiration (see Lesson 1) and are therefore written without the ‘h’.

e.g. uA:Mini — piece of firewood inAmni — firewood

urAango — fence

intango — fences

upAondo — horn

uppondo — horns

and explosive ‘bh’ becomes implosive ‘b’:

uAAalu — cave

imAalu — caves

Note that all the nouns of this class are impersonal (except for ‘usane —

baby’), so that in this way the singular nouns can be distinguished from the

singular nouns of the U/O class which are personal.

2 Concords

a) Subject concords Prefix ULU-gives concord LU-.

e.g. Uluthi /ungaphi? — Where is the stick?

Lungaphi? — Where is it?

Usane /uyakhala — The baby is crying

¿^Hyakhala — He/She is crying

33

Prefix IZIN-/IZIM- gives concord ZI-.

Where are the sticks?

e.g. Izinti zi'ngaphi ?

Where are they?

Z/ngaphi?

Where are the caves?

Imbalu z/ngaphi?

Where are they?

Z/ngaphi?

The babies are crying

Insane z/yakhala

They are crying

Z/yakhaia

b) Object concords

Singular: -LUe.g. Ngiya///bona uluthi — I see the stick

Ngiya/i/bona — I see it

Ngiya///bona usane — I see the baby

Ngiya///bona — I see him/her

Plural: -ZIe.g. Ngiyaz/bona izinti — I see the sticks

Ngiyaz/bona — I see them

Ngiyaz/bona insane — I see the babies

Ngiyaz/bona — I see them

3 The negative

e.g. Usane kalukhali — The baby is not crying

Ufudu kaludli — The tortoise is not eating

The babies are not crying

Insane kazikhali Imfudu kazidli — The tortoises are not eating

VOCABULARY

Prefix ULUuluthi

ulutho

stick

thing

Prefix IZINizinti

izinto

Prefix Uuchago

ucingo

ugwalo

ukhezo

ukhuni

usane

usuku

uthango

unwabu

unyawo

unwele

milk

wire

book, letter

spoon

piece of firewood

baby (at helpless stage)

day

fence

chameleon

foot

hair of head (one strand)

(iz)incingo

(iz)ingwalo

(iz)inkezo

(iz)inkuni

(iz)insane

(iz)insuku

(iz)intango

(iz)inwabu

(iz)inyawo

(iz)inwele

ubhalu

ufudu

uphahla

uphondo

cave

tortoise

roof

horn

Prefix IZIM(iz)imbalu

(iz)imfudu

(iz)impahla

(iz)impondo

34

Lesson 17

The noun:

UBU class

1 Prefix

There is only one prefix for this class of noun: UBU-.

Thus, ‘ubuchakide’ means either one weasel, or more than one;

‘ubunyonyo’ means either one ant, or more than one.

Most of the npuns in this class are abstract in meaning,

e.g. ubukhulu — greatness (from -khulu — great)

ubuhle — beauty (from -hie — beautiful)

Note: there are two nouns in this class which appear to have a prefix U-:

utshani — grass

utshwala — beer

In fact these nouns have developed from ‘ubu-ani’ and ‘ubu-ala’ by a

process called palatalisation, which will be explained later,

2 Concords

Subject concord: BU-.

Object concord: -BU-.

e.g. Ubunyonyo ¿«yaphuma — The ants are coming out

Ngiyaftttbona — I see them

Utshani ¿«ngaphi? — Where is the grass ?

Ngiyaittfuna — I want it

3 Negative

e.g. Ubunyonyo kabuphumi — The ants are not coming out

Utshani kabukhuli kuhle — The grass is not growing well

VOCABULARY

ubuchakide

ubunyonyo

ubuhlungu

ubuthongo

ubusuku

ubuso

utshani

utshwala

weasel/s

ant/s (small black variety)

pain/s; venom, poison/s

sleep

night/s

face/s

grass

beer

35

Lesson 18

The noun:

UKU class

1 Prefix

In this class are found verb infinitives used as nouns; therefore the prefix

is UKU-.

e.g. ukudla — food; eating; to eat

ukuphela — the end; to end

ukuthula — peace; quietness; to be quiet

ukulwa — fighting; to fight

2 Concords

Subject concord: KU-.

Object concord: -KU-.

e.g. Ukudla A:«ngaphi? — Where’s the food?

Ngiya/rttfuna — I want it

Ukulwa A:«yaphela — The fighting is ending

AsiA:«thandi ukulwa — We don’t like fighting

Note: the concord KU- may be used in a general way for the pronoun

‘it’, when it does not refer to any particular noun.

e.g. Kuyini? — What is it?

Kuyaqanda — It is cold

Kuyatshisa — It is hot

Kuhle — It is good/It is nice

Kulungile — It’s all right

It may even sometimes be used when there is a noun subject, instead of that

noun concord.

e.g. Kufika umuntu — There’s someone coming

Kukhala inyoni — There’s a bird crying

3 Negative

e.g. Ukulwa kakupheli — The fighting is not ending

Ukuthula kakufiki — Peace does not come

36

Lesson 19

Nouns of foreign origin

There are some nouns which have been taken into the language from

Enghsh and Afrikaans, their pronunciation adapted to the Ndebele

speech sounds and a prefix attached. This is a process which is going on all

the time, but it will be helpful to sort out some of the well established

nouns of this type.

1 Nouns with singular prefix I-, plural prefix AMAMost foreign nouns are given these prefixes, which put them into the

ILI/AMA class, with concords LI- and A-.

e.g. /pholisa /»yafika — The policeman is coming

/4/Twpholisa oyafika — The police are coming

L/ngaphi ibhasikili? — Where’s the bicycle?

Ngiya/Zfuna — I want it

Siyawafuna a/nabhasikili — We want the cycles

However, you will find that in speech people are not very careful about

the way they use these nouns with prefix I- (the singular). Often they will

use the concord I- (from prefix IN-):

e.g. Ijesi mgaphi? — Where is the jersey?

Ngiyay/funa — I want it

In some instances either concord may be used. Where a noun has been

definitely accepted into one or other class, this is indicated in the

vocabulary.

2 Nouns in the IN/IZIN class

Some of the foreign nouns put into this class begin with ‘m’ or ‘n’.

e.g. -moto — car; -mali — money;

Imali mgaphi? Ngiyay/dinga — Where’s the money? I’m looking

for it

Izimota z/yahamba — The cars are going

Injini /hamba kuhle — The engine goes well

3 Nouns in the ISI/IZI class

An initial ‘s’ in the foreign noun usually means it will be put in this class,

e.g. Isikolo s/ngaphi? Ngiyafidinga? — Where’s the school? I’m

looking for it

Ngiyasifuna isitulo — I want the chair/stool

4 Nouns in the U/O class

These will be mostly people

e.g. Udokotela ungaphi? — Where is the doctor?

Ngiyamdinga — I’m looking for him

Otitshala hayafiindisa — The teachers are teaching

37

But note that in the plural these nouns are sometimes given prefix AMAe.g. /Imatitshala ayafundisa — The teachers are teaching

Ngiyatvflbona a/nadokotela — I see the doctors

S Other noon classes

Odd nouns may be put into other classes,

e.g. t/AMtshina «hamba kuhle — The machine goes well

//n/tshina /hamba kuhle — The machines go well

VOCABULARY

Concord LIibhasikili

ibhatshi

ibhulugwe

idamu

idolobho

igabha

iphephandaba

ipholisa

ipulazi

itshukela

ivili

iwindi

bicycle

jacket

pair of trousers

dam

town

fat

tin

newspaper

policeman

farm

sugar

wheel

window

Concord Iibhasi

bus

ifasikoti

apron

ifotsholo

shovel, spade

ifulawa

flour

ijesi

jersey

ikhiye

key, lock

inkomitsho/inkomitshi cup

Concord Aamabhasikili

amabhatshi

amabhulugwe

amadamu

amadolobho

amafutha (no singular)

amagabha

amaphephandaba

amapholisa

amapulazi

amavili

amawindi

Concord Aamabhasi

amafasikoti

amafotsholo

amajesi

amakhiye

amankomitsho/

amankomitshi

isepa

itafula

itiye

iyembe

soap

table

tea

shirt

Concord Iinditshi

injini

imali

imota

impompi

dish, bowl

engine

money

motor car

pump, tap, water pipe

Concord Z lizinditshi

izinjini

izimali

izimota

izimpompi

Concord SIisando

isibhedlela

hammer

hospital

Concord Z lizando

izibhedlela

38

amatafula

amayembe

isikolo

isitimela

isitolo

isitulo

Concord Uudokotela

unesi

utitshala

Concord Uumtshina

umbheda

school

train, steam engine

shop, store

stool, chair

doctor

nurse

schoolteacher

machine

bed

izikolo

izitimela

izitolo

izitulo

Concord BAodokotela

onesi

otitshala

Concord Aamadokotela

amanesi

amatitshala

Concord Iimitshina

TABLE OF NOUN PREFIXES AND CONCORDS

UMfana; UMUntu; UMelusi

ABAfana; ABAntu; ABelusi

Ubaba

Obaba

UMfula; UMUthi

IMIfula; IMIthi

ILItshe; Ijaha

AMAtshe; AMAjaha

ISItsha; ISalukazi

IZItsha; IZalukazi

INja; IMvu

IZINja; IZIMvu

ULUthi; Ukhezo; Ubhalu

IZINti; INkezo; IMbalu

UBUnyonyo

UKUdla

Subject concord

U

BA

U

BA

U

I

LI

A

SI

ZI

I

ZI

LU

ZI

BU

KU

Object concord

M

BA

M

BA

WU

YI

LI

WA

SI

ZI

YI

ZI

LU

ZI

BU

KU

39

Lesson 20

The locative demonstrative (here is)

The locative demonstrative is the term used to designate the part of

speech which is used when one indicates the person or object. In English

we say, ‘Here is the child’, ‘Here are the books’, and so on.

In Ndebele the locative demonstrative is one word, beginning NAN- or

NAM-, but with a different ending to agree with each different noun

prefix:

e.g. Umama nangu OR Nangu umama — Here is mother

Izinja nanzi OR Nanzi izinja — Here are the dogs

There are three positions in Ndebele.

1 ‘Here is’ poses no special problems.

2 ‘There is’ - There are two positions in Ndebele indicated by two

different forms.

a) If you wish to point out to a person an object, and that person is

close to the object, but you are not, you use the form ‘nango’.

b) If you wish to point out to a person an object, and that person is next

to you, you use the form ‘nanguya’ or ‘nanguyana’.

First position: The final vowel will be the same as the vowel of the noun

concord, and the preceding consonant changes according to which class of

noun is used:

e.g. Nangu umntwana — Here’s the child

Nanz/ izinja

— Here are the dogs

Nanka amaqanda — Here are the eggs

Second position: This is formed by changing the final vowel of the

locative demonstrative to ‘o’:

e.g. Nangu umntwana — Here’s the child

Nango umntwana — There’s the child

Nanzi izinja — Here are the dogs

Nanzo izinja — There are the dogs

Nanka amaqanda — Here are the eggs

Nanko amaqanda — There are the eggs

Third position: This is formed by adding the suffix ‘-ya’ or ‘-yana’ to the

first position:

e.g. Nangu umntwana

Nanguya umntwana/Nanguyaaa umntwana — There’s the child

(over there)

Nanzi izinja

Nanziya/Nanziyawafizinja — There are the dogs (over there)

Nanka amaqanda

Nankaya/Nankayana amaqanda — There are the eggs (over there)

40

Note: if the shorter form, ending in ‘-ya’, is used, the stress in speech

falls on the final syllable, an exception to the rule,

e.g. Nanka;»'aaniaqanda; Izinjananziyo

Any of the locative demonstratives may be placed either before or after

their noun, and they may also be used on their own.

e.g. Ungaphi umganu ? Nanku — Where is the plate? Here it is

TABLE OF LOCATIVE DEMONSTRATIVES

Noun prefix

UMABAUOUMIMIILIAMAISIIZIIN/IMIZIN/IZIMULUIZINUBUUKU-

First position

Second position

nangu umntwana

nango

nampa abantwana

nampo

nangu ubaba

nango

nampa obaba

nampo

nanku umganu

nanko

nanso

nansi imiganu

nanto

nanti iqanda

папка amaqanda

nanko

nansi isitsha

nanso

nanzo

nanzi izitsha

nansi inja

nanso

nanzi izipja

nanzo

nantu ukhezo

nanto

nanzi inkezo

nanzo

nampu ubunyonyo

nampo

nanko

nanku ukudla

Third position

nanguya/na

nampaya/na

nanguya/na

nampaya/na

nanlmya/na

nansiya/na

nantiya/na

nankaya/na

nansiya/na

nanziya/na

nansiya/na

nanziya/na

nantuya/na

nanziya/na

nampuya/na

nankuya/na

41

Lesson 21

Adverbs and relative stems

I

ADVERBS OF PLACE

— up

— down;

on the ground

phakathi

— inside

eduze

— near

phandle

— outside

khatshana

— far

phetsheya

— on the other side; overseas

lapha

— here

khona

— present

lapho

— there

khonapha — here

khonapho — there

laphaya/laphayana — over there

ngale — used when indicating the direction: that way; over

there

Learn these: phambili

emuva

in front

behind

phezulu

phansi

1 With verbs

Adverbs may be used after verbs, just as in English:

e.g. Angifuni ukuhlala lapha •— 1 don’t want to stay here

Omama bahamba phambili — The women go in front

Khangela phezulu, mntwana — Look up, child

Abantu bavela phetsheya — The people come from overseas

2 With no verb

Adverbs may be used without a verb, that is, where in English we use the

verb ‘to be’ (e.g. Mother is inside).

In Ndebele, although there is a verb ‘to be’ (ukuba), it is not used in

this construction. Merely place the required concord before the adverb,

e.g. Umama «phakathi — Mother is inside

Abantwana ¿»aphandle — The children are outside

Imbiza /phansi — The pot is on the ground

Ag/lapha — la m here

Note: if the adverb begins with a vowel, insert ‘s’ between concord and

adverb, to separate the vowels.

e.g. Umuzi useduze — The village is near

Inja ijemuva — The dog is behind

♦

Negative: use the negative KA* (or A-) with the concord:

e.g. Umama Araphakathi — Mother is not inside

Abantwana A:aZ>aphandle — The children are not outside

Imbiza /tay/phansi — The pot is not on the ground

Umuzi /raw«seduze — The village is not near

Inja A:ay/semuva — The dog is not behind

3 Khona

a) The adverb ‘khona’ means ‘present’. It does not in itself have any

42

sense of position or distance, as do ‘lapha’ and ‘lapho’, and so on. It may

be used to translate the English ‘here’ or ‘there’, if this only means presence

in a certain place.

e.g. Unyokoukhonana? — Is your mother here?/Isyour mother in?

Uyayazi iGwelo na? Ubaba uhlala khona

Do you know Gwelo? My father lives there

Ngifuna ukuya khona — I want to go there

‘Khona’ is commonly used in the following way:

Amanzi akhona na? — Is there any water?

Impuphu ikhona n a? — Is there any mealie meal?