Leptospirosis-Induced Myocarditis & Arrhythmias Case Report

advertisement

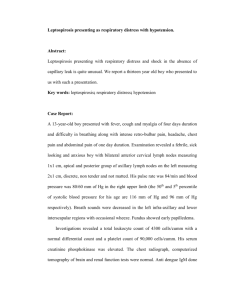

1179450 case-report20232023 HICXXX10.1177/23247096231179450Journal of Investigative Medicine High Impact Case ReportsSwarath et al Case Report Leptospirosis-Induced Myocarditis and Arrhythmias Journal of Investigative Medicine High Impact Case Reports Volume 11: 1–5 © 2023 American Federation for Medical Research https://doi.org/10.1177/23247096231179450 DOI: 10.1177/23247096231179450 journals.sagepub.com/home/hic Steven Swarath, MBBS1, Nicole Maharaj, MBBS1, Rajeev Seecheran, MBBS, MHA2, Valmiki Seecheran, MBBS, MSc1, Jessica Kawall, MBBS1, Stanley Giddings, MBBS3, and Naveen Anand Seecheran, MBBS (MD), MSc, FACP, FRCP(E), FACC, FESC, FSCAI3 Abstract Cardiac manifestations in leptospirosis usually involve atrial arrhythmias, conduction abnormalities, and nonspecific ST-T changes, while left ventricular dysfunction is rare. We present the case of a 45-year-old male without a pre-existing cardiovascular history who developed atrial fibrillation and atrial and ventricular tachycardia, in addition to new-onset cardiomyopathy in the setting of fulminant leptospirosis infection. Keywords leptospirosis, myocarditis, ventricular tachycardia, atrial tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, arrhythmia, heart failure Introduction Leptospirosis is a zoonotic disease caused by spirochetes of the genus Leptospira.1 Severe disease causes multisystem dysfunction, which includes cardiac involvement. Atrial fibrillation (AF), first-degree atrioventricular block, and nonspecific ST-T changes likely reflecting myocarditis are seen in patients with systemic infection. However, these patients rarely have significant left ventricular dysfunction (LVD).2 We present the case of a 45-year-old male without a preexisting cardiovascular history who developed AF and atrial (AT) and ventricular tachycardia (VT), in addition to newonset cardiomyopathy in the setting of fulminant leptospirosis infection. Case Report A 45-year-old South Asian male farmer with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department with chest pain and generalized myalgias. He was exposed to “flood waters” a week before admission. He also reported fever and “flu-like” symptoms, which seemingly resolved 2 days before seeking medical care. He was a lifelong nonsmoker and denied using alcohol or any illicit substances. There was no pertinent travel or pet history. His vital signs on admission were blood pressure of 86/58 mm Hg, heart rate of 102 beats per minute, pulse-oximetry 94% on room air, random blood glucose 184 mg/dL, and temperature of 36.4 °C. On physical examination, he was noted to be severely icteric. He had an S3 with no murmurs. Air entry was decreased, and there were occasional scattered crackles bilaterally. His abdomen was mildly distended, however, nontender. He was alert and oriented without any neurological deficits, and there was no anasarca with mild pitting edema to the tibial tuberosity bilaterally. His chest radiography revealed borderline cardiomegaly with mild interstitial edema, and initial admission 12-lead electro­ cardiogram indicated sinus rhythm at 94 beats per minute with no acute dynamic changes. The patient was immediately resuscitated with intravenous crystalloid infusion, and his electrolytes were repleted judiciously. His coronavirus rapid antigen test returned a negative result. 1 North Central Regional Health Authority, Mt. Hope, Trinidad and Tobago 2 Kansas University Medical Center, Wichita, USA 3 University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago Received March 31, 2023. Revised May 4, 2023. Accepted May 14, 2023. Corresponding Author: Naveen Anand Seecheran, MBBS (MD), MSc, FACP, FRCP(E), FACC, FESC, FSCAI, Department of Clinical Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of the West Indies, 2nd Floor, Building #67, Eric Williams Medical Sciences Complex, Mt. Hope, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago. Email: nseecheran@gmail.com Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage). 2 Journal of Investigative Medicine High Impact Case Reports Table 1. The Patient’s Admission Laboratory Data. Laboratory value Complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel and cardiac biomarkers White cell count Hemoglobin Platelets Serum sodium Serum potassium Serum creatinine Blood urea nitrogen Serum calcium Serum magnesium Fasting blood sugar Alanine aminotransferase Aspartate aminotransferase Alkaline phosphatase Serum albumin International normalized ratio Prothrombin time Activated partial thromboplastin time Total bilirubin Conjugated bilirubin Troponin I Creatine kinase Infectious diseases panel Erythrocyte sedimentation rate C-reactive protein Blood cultures Urine culture Human immunodeficiency virus enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay QuantiFERON-TB GOLD (Cellestis Limited, Carnegie, Victoria, Australia) Biofire Respiratory Panel (RP 2.1) (Biofire Diagnostics (Salt Lake City, UT, USA)) Respiratory pathogen panel (BioFire) tests COVID-19 test (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2019-nCoV Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel, Atlanta, GA) Leptospirosis immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies Hepatitis B surface antigen Hepatitis C IgM antibodies Hepatitis C immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies Dengue IgM antibodies Dengue IgG antibodies Malaria thick and thin smears Urine Legionella antigen Patient’s value Normal range 19.6 13.4 67 132 4.4 4.3 81 9.2 0.9 84 73 34 154 3.2 1.2 14.6 34 15.5 11.1 1.2 293 4.5-11.0 × 109/L 14.0-17.5 g/dL 156-373 × 103/µL 135-145 mEq/L 3.5-5.1 mEq/L 0.5-1.2 mg/dL 4-24 mg/dL 9.6-11.2 mg/dL 1.7-2.2 mg/dL 60-120 mg/dL 20-60 IU/L 5-40 IU/L 40-129 IU/L 3.5-5.5 g/dL 1-1.4 11-14 seconds 26-31 seconds 0.1-1.3 mg/dL 0.1-0.8 mg/dL 0.00-0.08 ng/mL 29-190 IU/L 55 42 Negative Negative Nonreactive Negative Negative 0-22 mm/h 0.0-1.0 mg/dL Positive or negative Positive or negative Nonreactive or reactive Positive or negative Positive or negative Negative Positive or negative Positive Negative Negative Negative Negative Negative Negative Negative Positive or negative Positive or negative Positive or negative Positive or negative Positive or negative Positive or negative Positive or negative Positive or negative Bold term indicates the patient’s admission diagnostic data. He was subsequently admitted to the medical intensive care unit, where he was empirically initiated on renallydosed intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam and tigecycline for suspected leptospirosis infection. He also received the routine management bundle for severe sepsis, excluding corticosteroid therapy. The following day, the patient incurred respiratory failure with severe hypoxemia and was commenced on high-flow noninvasive ventilation. A bedside 2-dimensional transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a moderate global hypokinesis with an estimated ejection fraction of 30% to 35% and mild-moderate mitral regurgitation. A noncontrast computed tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed basilar, bilateral air-space disease suggestive of aspiration pneumonitis. Eventually, his serologies returned positive for leptospirosis infection (Table 1). The patient endured a rocky clinical course. He alternated rapidly between AT, AF with rapid ventricular response, and VT, for which he was defibrillated and started on low-dose amiodarone infusion at 0.5 mg/min with vigilant hepatic function monitoring (Image 1). During his ensuing hospitalization, he remained clinically unstable and could not undergo further diagnostic testing to clinch or ascertain his Swarath et al 3 tentative diagnosis of nonischemic cardiomyopathy and myocarditis. He deteriorated into a vicious spiral of septic and cardiogenic shock for which he was admitted on multiple inotropic supports; however, he ultimately succumbed to his illness due to multiorgan failure. Discussion Image 1. The patient’s 12-lead electrocardiograms were interspersed during his hospital course. (A). The patient’s electrocardiogram displays atrial tachycardia with variable block and nonspecific ST-T changes. (B) The patient’s electrocardiogram displays atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, rate-related intraventricular conduction delay, and secondary ST-T changes. (C). The patient’s electrocardiogram displays ventricular tachycardia with several features, including atrioventricular disassociation, prolonged QRS duration exceeding 160 milliseconds, and ventricular concordance. Leptospirosis is a biphasic illness, initially presenting with an acute febrile episode that reflects early sepsis onset, typically 1 week in duration. Subsequently, there is an afebrile interval period, followed by a recrudescence of fever marking the onset of delayed immunity with sequelae of severe multiorgan dysfunction such as pulmonary hemorrhage, fulminant hepatic failure, acute kidney injury, and cardiac manifestations.3 The pathophysiology of the cardiac involvement of leptospirosis is not well elucidated. However, a glycoprotein fraction of the leptospiral cell wall has been postulated to inhibit the Na-K ATPase and implicated as a potential arrhythmogenic mechanism.4 The commonly observed electrocardiographic changes include conduction defects, nonspecific ST-T changes, and atrial arrhythmias.5-8 In addition, leptospirosis can be complicated by myocarditis and endocardial inflammation consistent with vasculitis.6 However, LVD is not usually seen.9 Our patient displayed a febrile illness with constitutional symptoms, one prior to the index presentation. He likely presented in the delayed immune phase of illness with evidence of multiorgan involvement of the hepatic, renal, hematologic, and cardiovascular systems. Due to the endemic nature of leptospirosis in Trinidad and the patient’s contextual history (farmer being exposed to “flood waters”), there was a high degree of clinical suspicion, hence the prompt diagnosis and management, confirmed by serological testing.10 Despite the association of leptospirosis and VT being exceedingly rare, our clinical acumen deduced that leptospirosis-induced myocarditis was the chief culprit. Acute myocarditis is associated with increased major adverse cardiovascular events, including short-term mortality.11 This diagnosis should be considered taking into account the patient’s symptomatology, the presence of VT (and non­ sustained VT on telemetry), and new-onset cardiomyopathy (CMP) diagnosed by transthoracic echocardiography.12,13 The Lake Louise criteria delineate diagnostic criteria for myocarditis; however, the patient remained critically ill and hemodynamically unstable throughout his hospitalization, precluding such an examination from being performed.14 The patient’s lack of pre-existing cardiovascular history, contributing comorbidities, and absence of calcium on chest computed tomographic scan also lent credence to this tentative diagnosis; however, we do acknowledge this is not definitive.12 Coronary angiography was also not performed to exclude an ischemic etiology due to his multiorgan dysfunction syndrome, specifically his acute kidney injury. 4 The mechanism of VT may be attributed to the myocardial inflammatory process secondary to a pathogenic infection that may continue even after myocardial recovery.15 The substrate involves an intricate milieu of formation of microreentry circuits triggered by the pro­arrhythmic effects of cytokines leading to electrical remodeling.16-18 Most cases with myocardial involvement describe normal or mildly reduced left ventricular function.7,8 Moderate to severely reduced left ventricular function is rarely encountered and reported.19,20 The patient also displayed a multitude of atrial arrhythmias, including sinus tachycardia, AT, and AF with rapid ventricular response. Atrial arrhythmias in leptospirosis have been well documented in the literature.21,22 These arrhythmias may result from a plethora of metabolic, electrolyte derangements, intravascular volume imbalances, and neurohormonal and catecholaminergic stress.23,24 Proposed mechanisms of these arrhythmias involve sympathetic nervous system–induced calcium entry into cardiac myocytes and spontaneous calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum.25 Our patient illustrated several of the aforementioned electrolyte abnormalities, including hyponatremia, hyper­ kalemia, hypomagnesemia, and hypocalcemia, all of which were aggressively corrected despite his critical illness physiology of severe sepsis and cardiorenal syndrome (Table 1). Currently, there are no specific treatment guidelines for leptospiral myocarditis other than treating the underlying sepsis and supportive therapy.26 Cardiac involvement portends a worse prognosis, and postmortem studies reveal a high prevalence of myocardial involvement.27,28 Our patient also displayed the dreaded Weil’s syndrome (jaundice, renal and hepatic failure), which is also associated with a high fatality rate.29,30 Our patient had clinical and laboratory prognosticators associated with a severe disease and a high fatality rate. He was initiated on parenteral beta-lactam antibiotic therapy while awaiting confirmation of the septic screen. Apart from beta-lactam antibiotics, intravenous doxycycline may be used to treat severe leptospirosis; however, this was not available in our setting. Tigecycline, a tetracycline antibiotic in the same class as doxycycline, has not been studied as an in vitro agent for treating human leptospirosis; however, it has been used as salvage therapy for multidrug-resistant bacteria. Recent evidence shows that tigecycline possesses both in vivo bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects on Leptospira strains.31 Despite it being associated with increased mortality among intensive care unit patients, the multidisciplinary team opted for a synergistic combination as the patient spiraled down further.32,33 Conclusion We present the case of a 45-year-old male without a preexisting cardiovascular history who developed AF and AT and VT, in addition to new-onset cardiomyopathy in the Journal of Investigative Medicine High Impact Case Reports setting of fulminant leptospirosis infection. The clinician should be aware of potentially lethal arrhythmias and newonset cardiomyopathy in a patient with leptospirosis. Authors’ Contribution All authors contributed equally to the manuscript, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript. Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Compliance With Ethics Guidelines and Standards All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed Consent Written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) for their anonymized information to be published in this article. ORCID iD Naveen Anand Seecheran https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7779-0181 Data Sharing Statement All available data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author. References 1. Khoo CY, Ng CT, Zheng S, Teo LY. An unusual case of fulminant leptospiral myocarditis: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2019;3(4):1-5. 2. Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P, et al. Braunwald’s Heart Disease E-Book: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014. 3. Bal AM. Unusual clinical manifestations of leptospirosis. J Postgrad Med. 2005;51(3):179-183. 4. Younes-Ibrahim M, Burth P, Castro-Faria M, et al. Effect of Leptospira interrogans endotoxin on renal tubular Na,KATPase and H,K-ATPase activities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997; 834:684-686. 5. Agampodi SB, Dahanayaka NJ, Bandaranayaka AK, et al. Regional differences of leptospirosis in Sri Lanka: observations from a flood-associated outbreak in 2011. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(1):e2626. 6. Shah K, Amonkar GP, Kamat RN, Deshpande JR. Cardiac findings in leptospirosis. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63(2):119-123. 7. Trivedi SV, Bhattacharya A, Amichandwala K, Jakkamsetti V. Evaluation of cardiovascular status in severe leptospirosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2003;51:951-953. Swarath et al 8. Rajiv C, Manjuran RJ, Sudhayakumar N, et al. Cardiovascular involvement in leptospirosis. Indian Heart J. 1996;48:691-694. 9. Pushpakumara J, Prasath T, Samarajiwa G, et al. Myocarditis causing severe heart failure—an unusual early manifestation of leptospirosis: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:80. 10. Peters A, Vokaty A, Portch R, et al. Leptospirosis in the Caribbean: a literature review. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2017;41:e166. 11. Kragholm KH, Lindgren FL, Zaremba T, et al. Mortality and ventricular arrhythmia after acute myocarditis: a nationwide registry-based follow-up study. Open Heart. 2021;8(2):806. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2021-001806 12. Caforio ALP. Myocarditis: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2020. 13. Caforio ALP, Marcolongo R, Basso C, et al. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of myocarditis. Heart. 2015;101:1332-1344. 14. Ferreira VM, Schulz-Menger J, Holmvang G, et al. Cardio­ vascular magnetic resonance in non-ischemic myocardial inflammation: expert recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:3158-3176. 15. Dello Russo A, Casella M, Pieroni M, et al. Drug-refractory ventricular tachycardias after myocarditis: endocardial and epicardial radiofrequency catheter ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:492-498. 16. Shenasa M. Arrhythmias in Cardiomyopathies, An Issue of Cardiac Electrophysiology Clinics. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015. 17. Cihakova D. Myocarditis. London, UK: Bod—Books on Demand; 2011. 18. Saito J, Niwano S, Niwano H, et al. Electrical remodeling of the ventricular myocardium in myocarditis: studies of rat experimental autoimmune myocarditis. Circ J. 2002;66(1): 97-103. 19. Zuin M, Rigatelli G, Roncon L. Severe heart dysfunction caused by leptospiral myocarditis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018; 99(5):1108-1109. 20. Forbat E, Rouhani MJ, Pavitt C, Patel S, Handslip R, Ledot S. Leptospirosis presenting as severe cardiogenic shock: a case report. J Intensive Care Soc. 2018;19(4):351-353. 5 21. Kouba SJ, Kobayashi T, Blount RJ, et al. Atrial flutter as a rare manifestation of leptospirosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:237693. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-237693 22. Škerk V, Markotić A, Puljiz I, et al. Electrocardiographic changes in hospitalized patients with leptospirosis over a 10-year period. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17(7):CR369-75. 23. Kuipers S, Klein Klouwenberg PMC, Cremer OL. Incidence, risk factors and outcomes of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with sepsis: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2014;18:688. 24. Walkey AJ, Wiener RS, Ghobrial JM, et al. Incident stroke and mortality associated with new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized with severe sepsis. JAMA. 2011;306:2248-2254. 25. Ter Keurs HEDJ Boyden PA. Calcium and arrhythmogenesis. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:457-506. 26. Navinan MR, Rajapakse S. Cardiac involvement in leptospirosis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:515-520. 27. Jayathilaka PGNS, Mendis ASV, Perera MHMTS, et al. An outbreak of leptospirosis with predominant cardiac involvement: a case series. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:265. 28. Chakurkar G, Vaideeswar P, Pandit SP, Divate SA. Cardio­ vascular lesions in leptospirosis: an autopsy study. J Infect. 2008;56(3):197-203. 29. Sharp TM, Rivera García B, Pérez-Padilla J, et al. Early indicators of fatal leptospirosis during the 2010 epidemic in Puerto Rico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(2):e0004482. 30. McBride AJA, Athanazio DA, Reis MG, et al. Leptospirosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:376-386. 31. Bertelloni F, Cilia G, Fratini F. Bacteriostatic and bactericidal effect of tigecycline on SPP. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020;9:80467. 32. Center for Drug Evaluation, Research. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns of increased risk of death with IV antibacterial Tygacil (tigecycline) and approves new Boxed Warning. In: U.S. Food and Drug Administration [Internet]. FDA, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/ fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-warns-increased-riskdeath-iv-antibacterial-tygacil-tigecycline 33. Wang J, Pan Y, Shen J, et al. The efficacy and safety of tigecycline for the treatment of bloodstream infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2017;16:24.