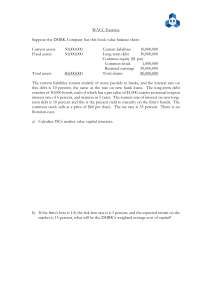

9 THE COST OF CAPITAL AND CAPITAL STRUCTURE Learning objectives After studying this chapter, you should have achieved the following learning objectives: ■ a firm understanding of how to calculate a company’s cost of capital and how to apply it appropriately in the investment appraisal process; ■ the ability to calculate the costs of different sources of finance used by a company and to calculate the weighted average cost of capital of a company; ■ an appreciation of why, when calculating the weighted average cost of capital, it is better to use market values than book values; ■ an understanding of how the capital asset pricing model can be used to calculate risk-adjusted discount rates for use in investment appraisal; ■ the ability to discuss critically whether or not a company can, by adopting a particular capital structure, influence its cost of capital. M09_WATS3037_07_SE_C09.indd 280 04/13/16 1:08 PM 9.1 CALCULATING THE COST OF INDIVIDUAL SOURCES OF FINANCE ■ ■ ■ INTRODUCTION The concept of the cost of capital, which is the rate of return required on invested funds, plays an important role in corporate finance theory and practice. A company’s cost of capital is (or could be) used as the discount rate in the investment appraisal process when using techniques such as net present value and internal rate of return. If we assume that a company is rational, it will want to raise capital by the cheapest and most efficient methods, thereby minimising its average cost of capital. This will have the effect of increasing the net present value of the company’s projects and hence its market value. For a company to try to minimise its average cost of capital, it first requires information on the costs associated with the different sources of finance available to it. Second, it needs to know how to combine these different sources of finance in order to reach its optimal capital structure. The importance of a company’s capital structure, like the importance of dividend policy, has been the subject of intense academic debate. As with dividends, Miller and Modigliani argued, somewhat against the grain of academic thought at the time, that a company’s capital structure was irrelevant in determining its average cost of capital. They later revised their views to take account of the tax implications of debt finance. If market imperfections are also considered, it can be argued that capital structure does have relevance to the average cost of capital. In practice, calculating a company’s cost of capital can be extremely difficult and time-consuming; it is also difficult to identify or prove that a given company has an optimal financing mix. 9.1 CALCULATING THE COST OF INDIVIDUAL SOURCES OF FINANCE A company’s overall or weighted average cost of capital can be used as a discount rate in investment appraisal and as a benchmark for company performance, so being able to calculate it is a key skill in corporate finance. The first step in calculating the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is to find the cost of capital of each source of long-term finance used by a company. That is the purpose of this section. 9.1.1 Ordinary shares Equity finance can be raised either by issuing new ordinary shares or by using retained earnings. We can find the cost of equity (Ke) by rearranging the dividend growth model which is considered later in the book in Section 10.4.3: Ke = where: Ke D0 g P0 = = = = D0 11 + g2 P0 + g cost of equity current dividend or dividend to be paid shortly expected annual growth rate in dividends ex dividend share price 281 M09_WATS3037_07_SE_C09.indd 281 04/13/16 1:08 PM CHAPTER 9 THE COST OF CAPITAL AND CAPITAL STRUCTURE Retained earnings have a cost of capital equal to the cost of equity. A common misconception is to see retained earnings as a source of finance with no cost. It is true that retained earnings do not have servicing costs, but they do have an opportunity cost equal to the cost of equity, since if these funds were returned to shareholders they could have achieved a return equivalent to the cost of equity through personal reinvestment. An alternative and arguably more reliable method of calculating the cost of equity is to use the capital asset pricing model (CAPM), considered earlier in Chapter 8. The CAPM allows shareholders to determine their required rate of return, based on the risk-free rate of return plus an equity risk premium. The equity risk premium reflects both the systematic risk of the company and the excess return generated by the market relative to risk-free investments. Using the CAPM, the cost of equity finance is given by the following linear relationship: where: Rj Rf bj Rm = = = = Rj = Rf + [(bj * 1Rm - Rf 2 2] the rate of return of share j predicted by the model the risk@free rate of return the beta coefficient of share j the return of the market 9.1.2 Preference shares Calculating the cost of preference shares is usually easier than calculating the cost of ordinary shares. This is because the dividends paid on preference shares are usually constant. Preference shares tend to be irredeemable and preference dividends are not tax deductible since they are a distribution of after-tax profits. The cost of irredeemable preference shares (Kps) can be calculated by dividing the dividend payable by the ex dividend market price as follows: Kps = Dividend payable Market price (ex dividend) When calculating the cost of raising new preference shares, the above expression can be modified, as can the dividend growth model, to take issue costs into account. 9.1.3 Bonds and convertibles There are three major types of bonds or loan notes: irredeemable bonds, redeemable bonds and convertible bonds. The cost of irredeemable bonds is calculated in a similar way to that of irredeemable preference shares. In both cases, the model being used is one that values a perpetual stream of cash flows (a perpetuity). Since the interest payments made on an irredeemable bond are tax deductible, it will have both a before- and an after-tax cost of debt. The before-tax cost of irredeemable bonds (Kib) can be calculated as follows: Kib = Interest rate payable Market price of bond 282 M09_WATS3037_07_SE_C09.indd 282 04/13/16 1:08 PM 9.1 CALCULATING THE COST OF INDIVIDUAL SOURCES OF FINANCE The after-tax cost of debt is then easily obtained if the corporate taxation rate (CT) is assumed to be constant: Kib 1after tax2 = Kib(1 - CT) To find the cost of redeemable bonds we need to find the overall return required by providers of debt finance, which combines both revenue (interest) and capital (principal) returns. This is equivalent to the internal rate of return (Kd) of the following valuation model: P0 = where: P0 I CT RV Kd n = = = = = = I11 - CT 2 11 + Kd 2 + I11 - CT 2 11 + Kd 2 2 + I11 - CT 2 11 + Kd 2 3 + ### + I11 - CT 2 + RV current ex interest market price of bond annual interest payment corporate taxation rate redemption value cost of debt after tax number of years to redemption 11 + Kd 2 n Note that this equation will give us the after-tax cost of debt. If the before-tax cost is required, I and not I(1 – CT) should be used. Linear interpolation can be used to estimate Kd (see ‘The internal rate of return method’, Section 6.4). Alternatively, instead of using linear interpolation, the before-tax cost of debt can be estimated using the bond yield approximation model developed by Hawawini and Vora (1982): P - NPD d n Kd = P + 0.61NPD - P2 I + c where: I P NPD n = = = = annual interest payment par value or face value net proceeds from disposal (market price of bond) number of years to redemption The after-tax cost of debt can be found using the company taxation rate (CT): Kd 1after tax2 = Kd(1 - CT) The cost of capital of convertible debt is more difficult to calculate. To find its cost we must first determine whether conversion is likely to occur (see ‘The valuation of convertible bonds’, Section 5.7). If conversion is not expected, we ignore the conversion value and treat the bond as redeemable debt, finding its cost of capital using the linear interpolation or bond approximation methods described above. If conversion is expected, we find the cost of capital of convertible debt using linear interpolation and a modified version of the redeemable bond valuation model given earlier. We modify the valuation model by replacing the number of years to redemption (n) with the number of years to conversion, and replacing the redemption value (RV) with the expected future conversion value (CV) (see ‘Market value’, Section 5.7.2). 283 M09_WATS3037_07_SE_C09.indd 283 04/13/16 1:08 PM CHAPTER 9 THE COST OF CAPITAL AND CAPITAL STRUCTURE It must be noted that an after-tax cost of debt is appropriate only if the company is in a profitable position, i.e. it has taxable profits against which to set its interest payments. 9.1.4 Bank borrowings The sources of finance considered so far have all been tradeable securities and have a market price to which interest or dividend payments can be related in order to calculate their cost. This is not the case with bank borrowings, which are not in tradeable security form and which do not have a market value. To approximate the cost of bank borrowings, therefore, the average interest rate paid on the loan should be taken, making an appropriate adjustment to allow for the tax deductibility of interest payments. The average interest rate can be found by dividing the interest paid on bank borrowings by the average amount of bank borrowings for the year. Alternatively, the cost of debt of any bonds or traded debt issued by a company can be used as an approximate value for the cost of debt of its bank borrowings. 9.1.5 The relationship between the costs of different sources of finance When calculating the costs of the different sources of finance used by a company, a logical relationship should emerge between the cost of each source of finance on the one hand and the risk faced by each supplier of finance on the other. Equity finance represents the highest level of risk faced by investors. This is due both to the uncertainty surrounding dividend payments and capital gains, and to the ranking of ordinary shares at the bottom of the creditor hierarchy (see Figure 9.1) should a company go into liquidation. New equity issues therefore represent the most expensive source of finance, with retained earnings working out slightly cheaper owing to the savings on issue costs over a new equity issue. The cost of capital of preference shares will be less than the cost of equity for two reasons. First, preference dividends must be paid before ordinary dividends; hence, there is less risk of their not being paid. Second, preference shares rank higher in the creditor hierarchy than ordinary shares and so there is less risk of failing to receive a share of liquidation proceeds. 1 Fixed charge creditors 2 Costs of liquidation Increasing priority 3 Preferential creditors (including employees, PAYE and VAT) 4 Floating charge creditors Decreasing priority 5 Unsecured creditors 6 Preference shareholders 7 Ordinary shareholders Figure 9.1 Creditor hierarchy and the order of asset distribution on bankruptcy 284 M09_WATS3037_07_SE_C09.indd 284 04/13/16 1:08 PM 9.2 CALCULATING WEIGHTED AVERAGE COST OF CAPITAL There is no uncertainty with respect to interest payments on debt, unless a company is likely to be declared bankrupt. Debt is further up the creditor hierarchy than both preference shares and ordinary shares, implying that debt finance has a lower cost of capital than both. Whether bank borrowings are cheaper than bonds will depend on the relative costs of obtaining a bank loan and issuing bonds, on the amount of debt being raised, and on the extent and quality of security used. Generally speaking, the longer the period over which debt is raised, the higher will be its cost of capital: this is because lenders require higher rewards for giving up their purchasing power for longer periods of time. Additionally, the risk of default also increases with time. The cost of capital convertible debt depends on when and whether the debt is expected to convert into ordinary shares. If convertible debt is not expected to convert, its cost of capital will be similar to the cost of capital of redeemable bonds of a similar maturity. If convertible debt is expected to convert, its cost of capital will be between those of redeemable bonds and ordinary shares. The longer the time period before conversion, the closer will be the cost of capital of convertible debt to that of redeemable bonds and vice versa. The relationships discussed above are evident in the example of a WACC calculation given below. 9.2 CALCULATING WEIGHTED AVERAGE COST OF CAPITAL Once the costs of a company’s individual sources of finance have been found, the overall WACC can be calculated. In order to calculate the WACC, the costs of the individual sources of finance are weighted according to their relative importance as sources of finance. The WACC can be calculated either for the existing capital structure (average basis) or for additional incremental finance (marginal basis). The problem of average versus marginal basis WACC is discussed in the next section. The WACC calculation for a company financed solely by debt and equity finance is represented by: WACC = where: Ke E Kd CT D = = = = = Kd 11 - CT 2 * D Ke * E + 1D + E2 1D + E2 cost of equity value of equity before@tax cost of debt corporate taxation rate value of debt This equation will expand in proportion to the number of different sources of finance used by a company. For instance, for a company using ordinary shares, preference shares and both redeemable and irredeemable bonds, the equation will become: WACC = Kps * P Kib 11 - CT 2Di Krb 11 - CT 2Dr Ke * E + + + E + P + Di + Dr E + P + Di + Dr E + P + Di + Dr E + P + Di + Dr 285 M09_WATS3037_07_SE_C09.indd 285 04/13/16 1:08 PM CHAPTER 9 THE COST OF CAPITAL AND CAPITAL STRUCTURE where P, Di and Dr are the value of preference shares, irredeemable bonds and redeemable bonds, respectively. 9.2.1 Market value weightings or book value weightings? We now need to determine the weightings to be attached to the costs of the different sources of finance. The weightings allow the calculated average to reflect the relative proportions of capital used by a company. We must choose between book values or market values. Book values are easily obtained from a company’s accounts whereas market values can be obtained from the financial press and from a range of financial databases. While book values are easy to obtain, using them to calculate the WACC cannot be recommended. Book values are based on historical costs and rarely reflect the current required return of providers of finance, whether equity or debt. The nominal value of an ordinary share, for example, is usually only a fraction of its market value. In the following example, an ordinary share with a nominal value of £1 has a market value of £4.17. Using book values will therefore understate the impact of the cost of equity finance on the average cost of capital. As the cost of equity is always greater than the cost of debt, this will lead to the WACC being underestimated. This can be seen in the following example by comparing the WACC calculated using market values with the WACC calculated using book values. If the WACC is underestimated, unprofitable projects will be accepted. As mentioned earlier, some sources of finance, such as bank loans, do not have market values. There is no reason, theoretically, why book values and market values cannot be used in conjunction with each other. Hence when making WACC calculations it is recommended to use as many market values as possible. Example Calculating weighted average cost of capital Strummer plc is calculating its current weighted average cost of capital on both a book value and a market value basis. You have the following information: Financial position statement as at 31 December Non-current assets Current assets Current liabilities 5% bonds (redeemable in 6 years) 9% irredeemable bonds Bank loans Ordinary shares (50p nominal value) 7% preference shares (£1 nominal value) Reserves £000 33,344 15,345 (9,679) (4,650) (8,500) (3,260) 22,600 6,400 9,000 7,200 22,600 286 M09_WATS3037_07_SE_C09.indd 286 04/13/16 1:08 PM 9.2 CALCULATING WEIGHTED AVERAGE COST OF CAPITAL 1 The current dividend, shortly to be paid, is 23p per share. Dividends in the future are expected to grow at a rate of 5 per cent per year. 2 Corporation tax is currently 30 per cent. 3 The interest rate on bank borrowings is currently 7 per cent. 4 Stock market prices as at 31 December (all ex dividend or ex interest): Ordinary shares Preference shares 5% bonds 9% irredeemable bonds £4.17 89p £96 per £100 bond £108 per £100 bond Step one: Calculating the costs of individual sources of finance 1 Cost of equity: using the dividend growth model: Ke = [D0(1 + g)>P0] + g = [23 * (1 + 0.05)/417] + 0.05 = 10 .8 per cent 2 Cost of preference shares: Kps = 8>89 = 9.0 per cent 3 Cost of redeemable bonds (after tax): using the Hawawini–Vora bond yield approximation model: Krb = 5 + 1100 - 962 >6 100 + 0.6196 - 1002 Krb(before tax) = 5 .8% Krb(after tax) = 5 .8 * (1 - 0 .30) = 4 .1 per cent 4 Cost of bank loans (after tax): Kbl 1after tax2 = 7 * (1 - 0.30) = 4.9 per cent 5 Cost of irredeemable bonds (after tax): Kib 1after tax2 = 9 * (1 - 0.30)>108 = 5.8 per cent Step two: Calculating book and market values of individual sources of finance Source of finance Ordinary shares Preference shares Redeemable bonds Irredeemable bonds Bank loans Total Book value (£000) 6,400 + 7,200 = 13,600 9,000 4,650 8,500 3,260 39,010 Market value (£000) 6,400 * 4.17 * 2 = 53,376 9,000 * 0.89 = 8,010 4,650 * 96/100 = 4,464 8,500 * 108/100 = 9,180 3,260 78,290 ➨ 287 M09_WATS3037_07_SE_C09.indd 287 04/13/16 1:08 PM CHAPTER 9 THE COST OF CAPITAL AND CAPITAL STRUCTURE Step three: Calculating WACC using book values and market values WACC (book values) = (10 .8% * 13,600/39,010) + (9 .0% * 9,000/39,010) + (4 .1% * 4,650/39,010) + (4 .9% * 3,260/39,010) + (5 .8% * 8,500/39,010) = 8 .0 per cent WACC (market values) = (10 .8% * 53,376/78,290) + (9 .0% * 8,010/78,290) + (4 .1% * 4,464/78,290) + (4 .9% * 3,260/78,290) + (5 .8% * 9,180/78,290) = 9 .4 per cent 9.3 AVERAGE AND MARGINAL COST OF CAPITAL As mentioned earlier, the cost of capital can be calculated in two ways. If it is calculated on an average basis using balance sheet data and book values or market values as weightings, as in the above example, it represents the average cost of capital currently employed. This cost of capital represents historical financial decisions. If it is calculated as the cost of the next increment of capital raised by a company, it represents the marginal cost of capital. The relationship between average (AC) cost of capital and marginal (MC) cost of capital is shown in Figure 9.2. The relationship between the average cost and marginal cost curves can be explained as follows. When the marginal cost is less than the average cost of capital, the average cost of capital will fall. Once the marginal cost rises above the average cost of capital, however, the marginal cost of capital will pull up the average cost of capital, albeit at a slower rate than that at which the marginal cost is rising. Should we use the marginal or the average cost of capital when appraising investment projects? Strictly speaking, the marginal cost of capital raised to finance an investment project should be used rather than an average cost of capital. One problem with calculating Cost (%) AC MC 0 Gearing (debt/equity) Figure 9.2 The marginal cost and the average cost of capital 288 M09_WATS3037_07_SE_C09.indd 288 04/13/16 1:08 PM