Uploaded by

naverzen

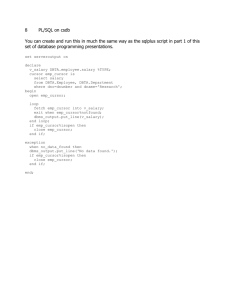

PL/SQL SQL Statements & Data Manipulation

INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME

• Determine the SQL statements that can be directly included in a

PL/SQL executable block.

• Manipulate data with DML statements in PL/SQL.

• Use transaction control statements in PL/SQL.

• Make use of the INTO clause to hold the values returned by an SQL

statement.

SQL Statements in PL/SQL

You can use the following kinds of SQL statements in PL/SQL:

• SELECT statements to retrieve data from a database.

• DML statements, such as INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE, to

make changes to the database.

• Transaction control statements, such as COMMIT, ROLLBACK,

or SAVEPOINT, to make changes to the database permanent or to

discard them.

5

DDL/DCL Limitations in PL/SQL

• You cannot directly execute DDL and DCL statements

because they are constructed and executed at run time—

that is, they are dynamic.

• There are times when you may need to run DDL or DCL

within PL/SQL.

• The recommended way of working with DDL and DCL

within PL/SQL is to use Dynamic SQL with the EXECUTE

IMMEDIATE statement.

6

SELECT Statements in PL/SQL

Retrieve data from a database into a PL/SQL variable with a

SELECT statement so you can work with the data within

PL/SQL.

SELECT

INTO

select_list

{variable_name[, variable_name]...

| record_name}

FROM

table

[WHERE condition];

7

Using the INTO Clause

• The INTO clause is mandatory and occurs between the

SELECT and FROM clauses.

• It is used to specify the names of PL/SQL variables that

hold the values that SQL returns from the SELECT clause.

DECLARE

v_emp_lname employees.last_name%TYPE;

BEGIN

SELECT last_name

INTO v_emp_lname

FROM employees

WHERE employee_id = 100;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('His last name is ' || v_emp_lname);

END;

8

Retrieving Data in PL/SQL Example

You must specify one variable for each item selected, and

the order of the variables must correspond with the order of

the items selected.

DECLARE

v_emp_hiredate employees.hire_date%TYPE;

v_emp_salary

employees.salary%TYPE;

BEGIN

hire_date, salary

SELECT

v_emp_hiredate, v_emp_salary

INTO

employees

FROM

WHERE employee_id = 100;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Hiredate: ' || v_emp_hiredate);

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Salary: '|| v_emp_salary);

END;

9

Retrieving Data in PL/SQL Embedded Rule

• SELECT statements within a PL/SQL block fall into the ANSI

classification of embedded SQL for which the following rule

applies: embedded queries must return exactly one row.

• A query that returns more than one row or no rows generates

an error.

DECLARE

v_salary employees.salary%TYPE;

BEGIN

SELECT salary INTO v_salary

FROM employees;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(' Salary is : ' || v_salary);

END;

ORA-01422: exact fetch returns more than requested number of rows

10

Retrieving Data in PL/SQL Example

Return the sum of the salaries for all the employees in the

specified department.

DECLARE

v_sum_sal NUMBER(10,2);

v_deptno NUMBER NOT NULL := 60;

BEGIN

SELECT SUM(salary) -- group function

INTO v_sum_sal FROM employees

WHERE department_id = v_deptno;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Dep #60 Salary Total: ' || v_sum_sal);

END;

11

Create Copy of Original Table

• It is very important that you do NOT modify the existing

tables (such as EMPLOYEES and DEPARTMENTS), because

they will be needed later in the course.

• The examples in this lesson use the COPY_EMP table.

• If you haven't already created the COPY_EMP table, do so

now by executing this SQL statement:

CREATE TABLE copy_emp

AS SELECT *

FROM employees;

13

Manipulating Data Using PL/SQL

Make changes to data by using DML commands within your

PLSQL block:

DELETE

• INSERT

• UPDATE

• DELETE

• MERGE

INSERT

UPDATE

MERGE

14

Manipulating Data Using PL/SQL

• You manipulate data in the database by using the DML

commands.

• You can issue the DML commands—INSERT, UPDATE,

DELETE, and MERGE—without restriction in PL/SQL.

– The INSERT statement adds new rows to the table.

– The UPDATE statement modifies existing rows in the table.

– The DELETE statement removes rows from the table.

15

Manipulating Data Using PL/SQL

• The MERGE statement selects rows from one table to

update and/or insert into another table.

• The decision whether to update or insert into the target

table is based on a condition in the ON clause.

– Note: MERGE is a deterministic statement—that is, you

cannot update the same row of the target table multiple

times in the same MERGE statement.

– You must have INSERT and UPDATE object privileges in the

target table and the SELECT privilege in the source table.

16

Inserting Data

• The INSERT statement adds new row(s) to a table.

• Example: Add new employee information to the

COPY_EMP table.

BEGIN

INSERT INTO copy_emp

(employee_id, first_name, last_name,

email,

hire_date, job_id, salary)

VALUES (99, 'Ruth', 'Cores',

'RCORES', SYSDATE, 'AD_ASST', 4000);

END;

• One new row is added to the COPY_EMP table.

17

Updating Data

• The UPDATE statement modifies existing row(s) in a table.

• Example: Increase the salary of all employees who are

stock clerks.

DECLARE

v_sal_increase employees.salary%TYPE := 800;

BEGIN

UPDATE copy_emp

SET salary = salary + v_sal_increase

WHERE job_id = 'ST_CLERK';

END;

18

Deleting Data

• The DELETE statement removes row(s) from a table.

• Example: Delete rows that belong to department 10 from

the COPY_EMP table.

DECLARE

v_deptno

employees.department_id%TYPE := 10;

BEGIN

DELETE FROM

copy_emp

WHERE department_id = v_deptno;

END;

19

Merging Rows

• The MERGE statement selects rows from one table to

update and/or insert into another table.

• Insert or update rows in the copy_emp table to match

the employees table.

BEGIN

MERGE INTO copy_emp c USING employees e

ON (e.employee_id = c.employee_id)

WHEN MATCHED THEN

UPDATE SET

c.first_name

= e.first_name,

c.last_name

= e.last_name,

c.email

= e.email,

. . .

WHEN NOT MATCHED THEN

INSERT VALUES(e.employee_id, e.first_name,...e.department_id);

END;

20

Getting Information From a Cursor

• Look again at the DELETE statement in this PL/SQL block.

DECLARE

employees.department_id%TYPE := 10;

v_deptno

BEGIN

copy_emp

DELETE FROM

WHERE department_id = v_deptno;

END;

• It would be useful to know how many COPY_EMP rows were

deleted by this statement.

• To obtain this information, we need to understand cursors.

21

What is a Cursor?

• Every time an SQL statement is about to be executed, the Oracle server

allocates a private memory area to store the SQL statement and the data that

it uses.

• This memory area is called an implicit cursor.

• Because this memory area is automatically managed by the

Oracle server, you have no direct control over it.

• However, you can use predefined PL/SQL variables, called implicit cursor

attributes, to find out how many rows were processed by the SQL statement.

23

Implicit and Explicit Cursors

There are two types of cursors:

• Implicit cursors: Defined automatically by Oracle for all SQL

data manipulation statements, and for queries that return

only one row.

– An implicit cursor is always automatically named “SQL.”

• Explicit cursors: Defined by the PL/SQL

programmer for queries that return more

than one row.

24

Cursor Attributes for Implicit Cursors

• Cursor attributes are automatically declared variables that

allow you to evaluate what happened when a cursor was last

used.

• Attributes for implicit cursors are prefaced with “SQL.”

• Use these attributes in PL/SQL statements, but not in SQL

statements.

• Using cursor attributes, you can test the

outcome of your SQL statements.

25

Cursor Attributes for Implicit Cursors

Attribute

Description

Boolean attribute that evaluates to TRUE if the

SQL%FOUND

most recent SQL statement returned at least

one row.

Boolean attribute that evaluates to TRUE if the

SQL%NOTFOUND

most recent SQL statement did not return

even one row.

An integer value that represents the number

SQL%ROWCOUNT

of rows affected by the most recent SQL

statement.

26

Using Implicit Cursor Attributes: Example 1

• Delete rows that have the specified employee ID from the

copy_emp table.

• Print the number of rows deleted.

DECLARE

v_deptno copy_emp.department_id%TYPE := 50;

BEGIN

DELETE FROM copy_emp

WHERE department_id = v_deptno;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(SQL%ROWCOUNT || ' rows deleted.');

END;

27

Using Implicit Cursor Attributes: Example 2

• Update several rows in the COPY_EMP table.

• Print the number of rows updated.

DECLARE

v_sal_increase

employees.salary%TYPE := 800;

BEGIN

UPDATE

copy_emp

SET

salary = salary + v_sal_increase

WHERE

job_id = 'ST_CLERK';

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(SQL%ROWCOUNT || ' rows updated.');

END;

28

Using Implicit Cursor Attributes: Good Practice

Guideline

• Look at this code which creates a table and then executes a

PL/SQL block.

• Determine what value is inserted into RESULTS.

CREATE TABLE results (num_rows NUMBER(4));

BEGIN

UPDATE

copy_emp

SET

salary = salary + 100

WHERE

job_id = 'ST_CLERK';

INSERT INTO results (num_rows)

VALUES (SQL%ROWCOUNT);

END;

29

Reference

PL/SQL User's Guide and Reference, Release 9.0.1

Part No. A89856-01

Copyright © 1996, 2001, Oracle Corporation. All rights

reserved.

Primary Authors: Tom Portfolio, John Russell

Oracle Academy

PLSQL S3L2 Retrieving Data in PL/SQL

PLSQL S3L3 Manipulating Data in PL/SQL

Copyright © 2019, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME

• Identify the uses and types of control structures.

• Construct an IF statement.

• Use CASE statements and CASE expressions.

• Use guidelines when using conditional control structures.

Controlling the Flow of Execution

• You can change the logical flow

of statements within the

PL/SQL block with a number of

control structures.

• This lesson introduces three

types of PL/SQL control

structures:

– Conditional constructs with the

IF statement

– CASE expressions

– LOOP control structures

LOOP

FOR

WHILE

35

IF Statements Structure

• The structure of the PL/SQL IF statement is similar to the

structure of IF statements in other procedural languages.

• It enables PL/SQL to perform actions selectively based on

conditions.

• Syntax:

IF condition THEN

statements;

[ELSIF condition THEN

statements;]

[ELSE

statements;]

END IF;

36

IF Statements

• Condition is a Boolean variable or expression that returns

TRUE, FALSE, or NULL.

• THEN introduces a clause that associates the Boolean

expression with the sequence of statements that follows it.

IF condition THEN

statements;

[ELSIF condition THEN

statements;]

[ELSE

statements;]

END IF;

37

Simple IF Statement

• This is an example of a simple IF statement with a THEN

clause.

• The v_myage variable is initialized to 31.

DECLARE

v_myage NUMBER := 31;

BEGIN

IF v_myage < 11

THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('I am a child');

END IF;

END;

38

IF THEN ELSE Statement

• The ELSE clause has been added to this example.

• The condition has not changed, thus it still evaluates to

FALSE.

DECLARE

v_myage NUMBER:=31;

BEGIN

IF v_myage < 11

THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('I am a child');

ELSE

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('I am not a child');

END IF;

END;

39

IF ELSIF ELSE Clause

• The IF statement

now contains

multiple ELSIF

clauses as well as

an ELSE clause.

• Notice that the

ELSIF clauses

add additional

conditions.

DECLARE

v_myage NUMBER := 31; BEGIN

IF v_myage < 11 THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('I am a child');

ELSIF v_myage < 20 THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('I am young');

ELSIF v_myage < 30 THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('I am in my twenties');

ELSIF v_myage < 40

THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('I am in my thirties');

ELSE

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('I am mature');

END IF;

END;

40

IF Statement with Multiple Expressions

• An IF statement can have multiple conditional

expressions related with logical operators, such as AND,

OR, and NOT.

• This example uses the AND operator.

• Therefore, it evaluates to TRUE only if both BOTH the first

name and age conditions are evaluated as TRUE.

DECLARE

v_myage

NUMBER

:= 31;

v_myfirstname VARCHAR2(11) := 'Christopher';

BEGIN

IF v_myfirstname ='Christopher' AND v_myage < 11

THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('I am a child named Christopher');

END IF;

END;

41

NULL Values in IF Statements

• In this example, the v_myage variable is declared but is

not initialized.

• The condition in the IF statement returns NULL, which is

neither TRUE nor FALSE.

• In such a case, the control goes to the ELSE statement

because, just NULL is not TRUE.

DECLARE

v_myage NUMBER;

BEGIN

IF v_myage < 11

THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('I am a child');

ELSE

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('I am not a child');

END IF;

END;

42

Handling Nulls

When working with nulls, you can avoid some common

mistakes by keeping in mind the following rules:

• Simple comparisons involving nulls always yield NULL.

• Applying the logical operator NOT to a null yields NULL.

• In conditional control statements, if a condition yields

NULL, it behaves just like a FALSE, and the associated

sequence of statements is not executed.

43

Handling Nulls Example

• In this example, you might expect the sequence of

statements to execute because a and b seem equal.

• But, NULL is unknown, so we don't know if a and b are

equal.

• The IF condition yields NULL and the THEN clause is

bypassed, with control going to the line following the

THEN clause.

a.:= NULL;

b.:= NULL;

...

IF a = b THEN … -- yields NULL, not TRUE and the

sequence of statements is not executed

END IF;

44

Using a CASE Statement

• Look at this IF statement. What do you notice?

• All the conditions test the same variable v_numvar.

• And the coding is very repetitive: v_numvar is coded

many times.

DECLARE

NUMBER;

v_numvar

BEGIN

...

IF

v_numvar = 5 THEN statement_1; statement_2;

ELSIF v_numvar = 10 THEN statement_3;

ELSIF v_numvar = 12 THEN statement_4; statement_5;

ELSIF v_numvar = 27 THEN statement_6;

ELSIF v_numvar ... – and so on

ELSE statement_15;

END IF;

...

END;

46

Using a CASE Statement

• Here is the same logic, but using a CASE statement.

• It is much easier to read. v_numvar is written only

once.

DECLARE

v_numvar

NUMBER;

BEGIN

...

CASE v_numvar

WHEN 5 THEN statement_1; statement_2;

WHEN 10 THEN statement_3;

WHEN 12 THEN statement_4; statement_5;

WHEN 27 THEN statement_6;

WHEN ... – and so on

ELSE statement_15;

END CASE;

...

END;

47

CASE Statements: An Example

A simple example to demonstrate the CASE logic.

DECLARE

v_num

NUMBER := 15;

v_txt

VARCHAR2(50);

BEGIN

CASE v_num

WHEN 20 THEN v_txt := 'number equals

WHEN 17 THEN v_txt := 'number equals

WHEN 15 THEN v_txt := 'number equals

WHEN 13 THEN v_txt := 'number equals

WHEN 10 THEN v_txt := 'number equals

ELSE v_txt := 'some other number';

END CASE;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_txt);

END;

20';

17';

15';

13';

10';

48

Searched CASE Statements

• You can use CASE statements to test for non-equality

conditions such as <, >, >=, etc.

• These are called searched CASE statements.

• The syntax is virtually identical to an equivalent IF

statement.

DECLARE

v_num

NUMBER := 15;

v_txt

VARCHAR2(50);

BEGIN

CASE

WHEN v_num > 20 THEN v_txt := 'greater than 20';

WHEN v_num > 15 THEN v_txt := 'greater than 15';

ELSE v_txt := 'less than 16';

END CASE;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_txt);

END;

49

Using a CASE Expression

• You want to assign a value to one variable that depends on

the value in another variable.

• Look at this IF statement.

• Again, the coding is very repetitive.

DECLARE

VARCHAR2(15);

v_out_var

NUMBER;

v_in_var

BEGIN

...

IF v_in_var = 1

THEN v_out_var := 'Low value';

ELSIF v_in_var = 50 THEN v_out_var := 'Middle value';

ELSIF v_in_var = 99 THEN v_out_var := 'High value';

ELSE v_out_var := 'Other value';

END IF;

...

END;

50

Using a CASE Expression

Here is the same logic, but using a CASE expression:

DECLARE

v_out_var

VARCHAR2(15);

v_in_var

NUMBER;

BEGIN

...

v_out_var := CASE v_in_var

WHEN 1 THEN 'Low value'

WHEN 50 THEN 'Middle value'

WHEN 99 THEN 'High value'

ELSE

'Other value'

END;

...

END;

51

CASE Expression Syntax

• A CASE expression selects one of a number of results and

assigns it to a variable.

• In the syntax, expressionN can be a literal value, such

as 50, or an expression, such as (27+23) or

(v_other_var*2).

variable_name :=

CASE selector

WHEN expression1 THEN result1

WHEN expression2 THEN result2

...

WHEN expressionN THEN resultN

[ELSE resultN+1]

END;

52

CASE Expression Example

What would be the result of this code if v_grade was

initialized as "C" instead of "A."

DECLARE

RESULT:

v_grade

CHAR(1) := 'A';

Grade: A

v_appraisal VARCHAR2(20);

Appraisal: Excellent

BEGIN

v_appraisal :=

Statement processed.

CASE v_grade

WHEN 'A' THEN 'Excellent'

WHEN 'B' THEN 'Very Good'

WHEN 'C' THEN 'Good'

ELSE 'No such grade'

END;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Grade: ' || v_grade ||

' Appraisal: ' || v_appraisal);

END;

53

CASE Expression: A Second Example

Determine what will be displayed when this block is

executed:

DECLARE

v_out_var

VARCHAR2(15);

v_in_var

NUMBER := 20;

BEGIN

v_out_var :=

CASE v_in_var

WHEN 1

THEN 'Low value'

WHEN v_in_var THEN 'Same value'

WHEN 20

THEN 'Middle value'

ELSE

'Other value'

END;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_out_var);

END;

54

Searched CASE Expression Syntax

• PL/SQL also provides a searched CASE expression, which

has the following form:

variable_name := CASE

WHEN search_condition1 THEN result1

WHEN search_condition2 THEN result2

...

WHEN search_conditionN THEN resultN

[ELSE resultN+1]

END;

• A searched CASE expression has no selector.

• Also, its WHEN clauses contain search conditions that yield

a Boolean value, not expressions that can yield a value of

any type.

55

Searched CASE Expressions: An Example

Searched CASE expressions allow non-equality conditions,

compound conditions, and different variables to be used in

different WHEN clauses.

DECLARE

v_grade

CHAR(1) := 'A';

v_appraisal VARCHAR2(20);

BEGIN

v_appraisal :=

CASE

-- no selector here

WHEN v_grade = 'A' THEN 'Excellent'

WHEN v_grade IN ('B','C') THEN 'Good'

ELSE 'No such grade'

END;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE ('Grade: '|| v_grade ||

' Appraisal ' || v_appraisal);

END;

56

How are CASE Expressions Different From

CASE Statements?

They are different because:

• CASE expressions return a value into a variable.

• CASE expressions end with END;

• A CASE expression is a single PL/SQL statement.

DECLARE

v_grade

CHAR(1) := 'A';

v_appraisal VARCHAR2(20);

BEGIN

v_appraisal :=

CASE

WHEN v_grade = 'A' THEN 'Excellent'

WHEN v_grade IN ('B','C') THEN 'Good'

ELSE 'No such grade'

END;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE ('Grade: '|| v_grade || ' Appraisal ' || v_appraisal);

END;

57

How are CASE Expressions Different From

CASE Statements?

• CASE statements evaluate conditions and perform

actions.

• A CASE statement can contain many PL/SQL statements.

• CASE statements end with END CASE;.

DECLARE

v_grade CHAR(1) := 'A';

BEGIN

CASE

WHEN v_grade = 'A' THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE ('Excellent');

WHEN v_grade IN ('B','C') THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE ('Good');

ELSE

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('No such grade');

END CASE;

END;

58

Reference

Oracle Academy

PLSQL S4L1 Retrieving Data in PL/SQL

PLSQL S4L2 Manipulating Data in PL/SQL

Copyright © 2019, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

PL/SQL User's Guide and Reference, Release 9.0.1

Part No. A89856-01

Copyright © 1996, 2001, Oracle Corporation. All rights

reserved.

Primary Authors: Tom Portfolio, John Russell

INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME

• Construct and identify loop statements.

Iterative Control: LOOP Statements

• Loops repeat a statement or a sequence of

statements multiple times.

• PL/SQL provides the following types of loops:

– Basic loops that perform repetitive actions

without overall conditions

– FOR loops that perform iterative actions based

on a counter

– WHILE loops that perform repetitive actions

based on a condition

64

Basic Loops

• The simplest form of a LOOP statement is the basic loop,

which encloses a sequence of statements between the

keywords LOOP and END LOOP.

• Use the basic loop when the statements inside the loop

must execute at least once.

66

Basic Loops Exit

• Each time the flow of execution reaches the END LOOP

statement, control is passed to the corresponding LOOP

statement that introduced it.

• A basic loop allows the execution of its statements at least

once, even if the EXIT condition is already met upon

entering the loop.

• Without the EXIT statement, the loop would never end

(an infinite loop).

BEGIN

LOOP

statements;

EXIT [WHEN condition];

END LOOP;

END;

67

Basic Loops Simple Example

• In this example, no data is processed.

• We simply display the loop counter each time we repeat

the loop.

DECLARE

v_counter

NUMBER(2) := 1;

BEGIN

LOOP

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Loop execution #' || v_counter);

v_counter := v_counter + 1;

EXIT WHEN v_counter > 5;

END LOOP;

END;

68

Basic Loops More Complex Example

In this example, three new location IDs for Montreal,

Canada, are inserted in the LOCATIONS table.

DECLARE

v_loc_id

locations.location_id%TYPE;

v_counter

NUMBER(2) := 1;

BEGIN

SELECT MAX(location_id) INTO v_loc_id FROM locations

WHERE country_id = 2;

LOOP

INSERT INTO locations(location_id, city, country_id)

VALUES((v_loc_id + v_counter), 'Montreal', 2);

v_counter := v_counter + 1;

EXIT WHEN v_counter > 3;

END LOOP;

END;

69

Basic Loops EXIT Statement

• You can use the EXIT statement to terminate a loop and

pass control to the next statement after the END LOOP

statement.

• You can issue EXIT as an action within an IF statement.

DECLARE

v_counter NUMBER := 1;

BEGIN

LOOP

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Counter is ' || v_counter);

v_counter := v_counter + 1;

IF v_counter > 10 THEN EXIT;

END IF;

END LOOP;

END;

70

Basic Loop EXIT Statement Rules

Rules:

• The EXIT statement must be placed inside a loop.

• If the EXIT condition is placed at the top of the loop

(before any of the other executable statements) and that

condition is initially true, then the loop exits and the other

statements in the loop never execute.

• A basic loop can contain multiple EXIT statements.

71

Basic Loop EXIT WHEN Statement

• Although the IF…THEN EXIT works to end a loop, the

correct way to end a basic loop is with the EXIT WHEN

statement.

• If the WHEN clause evaluates to TRUE, the loop ends and

control passes to the next statement following END LOOP.

DECLARE

v_counter NUMBER := 1;

BEGIN

LOOP

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Counter is ' || v_counter);

v_counter := v_counter + 1;

EXIT WHEN v_counter > 10;

END LOOP;

END;

72

WHILE Loops

• You can use the WHILE loop to repeat a sequence of

statements until the controlling condition is no longer

TRUE.

• The condition is evaluated at the start of each iteration.

• The loop terminates when the condition is FALSE or

NULL.

• If the condition is FALSE or NULL at the initial execution

of the loop, then no iterations are performed.

WHILE condition LOOP

statement1;

statement2;

. . .

END LOOP;

74

WHILE Loops

• In the syntax:

WHILE condition LOOP

statement1;

statement2;

. . .

END LOOP;

• Condition is a Boolean variable or expression (TRUE,

FALSE, or NULL)

• Statement can be one or more PL/SQL or SQL statements

PLSQL S4L4

Iterative Control: WHILE and FOR Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

75

WHILE

• In the syntax:

WHILE condition LOOP

statement1;

statement2;

. . .

END LOOP;

• If the variables involved in the conditions do not change

during the body of the loop, then the condition remains

TRUE and the loop does not terminate.

• Note: If the condition yields NULL, then the loop is

bypassed and control passes to the statement that follows

the loop.

PLSQL S4L4

Iterative Control: WHILE and FOR Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

76

WHILE Loops

• In this example, three new location IDs for Montreal,

Canada, are inserted in the LOCATIONS table.

• The counter is explicitly declared in this example.

DECLARE

v_loc_id

locations.location_id%TYPE;

v_counter

NUMBER := 1;

BEGIN

SELECT MAX(location_id) INTO v_loc_id FROM locations

WHERE country_id = 2;

WHILE v_counter <= 3 LOOP

INSERT INTO locations(location_id, city, country_id)

VALUES((v_loc_id + v_counter), 'Montreal', 2);

v_counter := v_counter + 1;

END LOOP;

END;

PLSQL S4L4

Iterative Control: WHILE and FOR Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

77

WHILE Loops

• With each iteration through the WHILE loop, a counter

(v_counter) is incremented.

• If the number of iterations is less than or equal to the

number 3, then the code within the loop is executed and a

row is inserted into the locations table.

DECLARE

v_loc_id

locations.location_id%TYPE;

v_counter

NUMBER := 1;

BEGIN

SELECT MAX(location_id) INTO v_loc_id FROM locations

WHERE country_id = 2;

WHILE v_counter <= 3 LOOP

INSERT INTO locations(location_id, city, country_id)

VALUES((v_loc_id + v_counter), 'Montreal', 2);

v_counter := v_counter + 1;

END LOOP;

END;

PLSQL S4L4

Iterative Control: WHILE and FOR Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

78

WHILE Loops

After the counter exceeds the number of new locations for

this city and country, the condition that controls the loop

evaluates to FALSE and the loop is terminated.

DECLARE

v_loc_id

locations.location_id%TYPE;

v_counter

NUMBER := 1;

BEGIN

SELECT MAX(location_id) INTO v_loc_id FROM locations

WHERE country_id = 2;

WHILE v_counter <= 3 LOOP

INSERT INTO locations(location_id, city, country_id)

VALUES((v_loc_id + v_counter), 'Montreal', 2);

v_counter := v_counter + 1;

END LOOP;

END;

PLSQL S4L4

Iterative Control: WHILE and FOR Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

79

FOR Loops Described

• FOR loops have the same general structure as the basic

loop.

• In addition, they have a control statement before the

LOOP keyword to set the number of iterations that PL/SQL

performs.

FOR counter IN [REVERSE]

lower_bound..upper_bound LOOP

statement1;

statement2;

. . .

END LOOP;

PLSQL S4L4

Iterative Control: WHILE and FOR Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

80

FOR Loop Rules

FOR loop rules:

• Use a FOR loop to shortcut the test for the number of

iterations.

• Do not declare the counter; it is declared implicitly.

• lower_bound .. upper_bound is the required

syntax.

FOR counter IN [REVERSE]

lower_bound..upper_bound LOOP

statement1;

statement2;

. . .

END LOOP;

PLSQL S4L4

Iterative Control: WHILE and FOR Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

81

FOR Loops Syntax

• Counter is an implicitly declared integer whose value

automatically increases or decreases (decreases if the

REVERSE keyword is used) by 1 on each iteration of the

loop until the upper or lower bound is reached.

• REVERSE causes the counter to decrement with each

iteration from the upper bound to the lower bound.

• (Note that the lower bound is referenced first.)

FOR counter IN [REVERSE]

lower_bound..upper_bound LOOP

statement1;

statement2;

. . .

END LOOP;

PLSQL S4L4

Iterative Control: WHILE and FOR Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

82

FOR Loops Syntax

• lower_bound specifies the lower bound for the range of

counter values.

• upper_bound specifies the upper bound for the range

of counter values.

FOR counter IN [REVERSE]

lower_bound..upper_bound LOOP

statement1;

statement2;

. . .

END LOOP;

PLSQL S4L4

Iterative Control: WHILE and FOR Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

83

FOR Loop Example

• You have already learned how to insert three new

locations for the country code CA and the city Montreal by

using the simple LOOP and the WHILE loop.

• This slide shows you how to achieve the same by using the

FOR loop.

DECLARE

v_loc_id

locations.location_id%TYPE;

BEGIN

SELECT MAX(location_id) INTO v_loc_id FROM locations

WHERE country_id = 2;

FOR i IN 1..3 LOOP

INSERT INTO locations(location_id, city, country_id)

VALUES((v_loc_id + i), 'Montreal', 2);

END LOOP;

END;

PLSQL S4L4

Iterative Control: WHILE and FOR Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

84

FOR Loop Guidelines

FOR loops are a common structure of programming

languages.

• A FOR loop is used within the code when the beginning

and ending value of the loop is known.

• Reference the counter only within the loop; its scope does

not extend outside the loop.

• Do not reference the counter as the target of an

assignment.

• Neither loop bound (lower or upper) should be NULL.

PLSQL S4L4

Iterative Control: WHILE and FOR Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

85

FOR Loop Expression Example

• While writing a FOR loop, the lower and upper bounds of

a LOOP statement do not need to be numeric literals.

• They can be expressions that convert to numeric values.

DECLARE

v_lower NUMBER := 1;

v_upper NUMBER := 100;

BEGIN

FOR i IN v_lower..v_upper LOOP

...

END LOOP;

END;

PLSQL S4L4

Iterative Control: WHILE and FOR Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

86

Nested Loop Example

• In PL/SQL, you can nest loops to multiple levels.

• You can nest FOR, WHILE, and basic loops within one

another.

BEGIN

FOR v_outerloop IN 1..3 LOOP

FOR v_innerloop IN REVERSE 1..5 LOOP

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Outer loop is: ' ||

v_outerloop ||

' and inner loop is: ' ||

v_innerloop);

END LOOP;

END LOOP;

END;

PLSQL S4L5

Iterative Control: Nested Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

88

Nested Loops

• This example contains EXIT conditions in nested basic

loops.

• What if you want to exit from the outer loop at step A?

DECLARE

CHAR(3) := 'NO';

v_outer_done

CHAR(3) := 'NO';

v_inner_done

BEGIN

LOOP

-- outer loop

...

-- inner loop

LOOP

...

...

-- step A

EXIT WHEN v_inner_done = 'YES';

...

END LOOP;

...

EXIT WHEN v_outer_done = 'YES';

...

END LOOP;

END;

PLSQL S4L5

Iterative Control: Nested Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

89

Loop Labels

Loop labels are required in this example in order to exit an

outer loop from within an inner loop

DECLARE

...

BEGIN

<<outer_loop>>

LOOP

-- outer loop

...

<<inner_loop>>

LOOP

-- inner loop

EXIT outer_loop WHEN ... -- exits both loops

EXIT WHEN v_inner_done = 'YES';

...

END LOOP;

...

EXIT WHEN v_outer_done = 'YES';

...

END LOOP;

END;

PLSQL S4L5

Iterative Control: Nested Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

90

Loop Labels

• Loop label names follow the same rules as other

identifiers.

• A label is placed before a statement, either on the same

line or on a separate line.

• In FOR or WHILE loops, place the label before FOR or

WHILE within label delimiters (<<label>>).

• If the loop is labeled, the label name can optionally be

included after the END LOOP statement for clarity.

PLSQL S4L5

Iterative Control: Nested Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

91

Loop Labels

Label basic loops by placing the label before the word LOOP

within label delimiters (<<label>>).

DECLARE

PLS_INTEGER := 0;

v_outerloop

PLS_INTEGER := 5;

v_innerloop

BEGIN

<<outer_loop>>

LOOP

v_outerloop := v_outerloop + 1;

v_innerloop := 5;

EXIT WHEN v_outerloop > 3;

<<inner_loop>>

LOOP

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Outer loop is: ' || v_outerloop ||

' and inner loop is: ' || v_innerloop);

v_innerloop := v_innerloop - 1;

EXIT WHEN v_innerloop = 0;

END LOOP inner_loop;

END LOOP outer_loop;

END;

PLSQL S4L5

Iterative Control: Nested Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

92

Nested Loops and Labels

• In this example, there are two loops.

• The outer loop is identified by the label

<<outer_loop>>, and the inner loop is identified by

the label <<inner_loop>>.

...BEGIN

<<outer_loop>>

LOOP

v_counter := v_counter + 1;

EXIT WHEN v_counter > 10;

<<inner_loop>>

LOOP

...

EXIT Outer_loop WHEN v_total_done = 'YES';

-- Leave both loops

EXIT WHEN v_inner_done = 'YES';

...

-- Leave inner loop only

...

END LOOP inner_loop;

END LOOP outer_loop;

END;

PLSQL S4L5

Iterative Control: Nested Loops

Copyright © 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

93

Reference

Oracle Academy

PLSQL S4L3 Iterative Control: Basic Loops

PLSQL S4L4 Iterative Control: While and For Loops

PLSQL S4L5 Iterative Control: Nested Loops

Copyright © 2019, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

PL/SQL User's Guide and Reference, Release 9.0.1

Part No. A89856-01

Copyright © 1996, 2001, Oracle Corporation. All rights

reserved.

Primary Authors: Tom Portfolio, John Russell

INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME

•

Create a record with the %ROWTYPE attribute.

•

Create user-defined PL/SQL records.

PL/SQL Records

• A PL/SQL record is a composite data type consisting of a

group of related data items stored as fields, each with its

own name and data type.

• You can refer to the whole record by its name and/or to

individual fields by their names.

• Typical syntax for defining a record, shown below, is similar

to what we used for cursors, we just replace the cursor

name with the table name.

record_name

table_name%ROWTYPE;

5

The Problem

• The EMPLOYEES table contains eleven columns:

EMPLOYEE_ID, FIRST_NAME,....,

MANAGER_ID, DEPARTMENT_ID.

• You need to code a single-row SELECT * FROM

EMPLOYEES in your PL/SQL subprogram.

• Because you are selecting only a single row, you do not

need to declare and use a cursor.

• How many scalar variables must you DECLARE to hold the

column values?

6

The Problem

• That is a lot of coding, and some tables will have even more

columns.

• Plus, what do you do if a new column is added to the table?

• Or an existing column is dropped?

DECLARE

v_employee_id employees.employee_id%TYPE;

v_first_name employees.first_name%TYPE;

v_last_name employees.last_name%TYPE;

v_email

employees.email%TYPE;

... FIVE MORE SCALAR VARIABLES REQUIRED TO MATCH THE TABLE

v_manager_id employees.manager_id%TYPE;

v_department_id employees.department_id%TYPE;

BEGIN

SELECT employee_id, first_name, ... EIGHT MORE HERE, department_id

INTO v_employee_id, v_first_name, ... AND HERE, v_department_id

FROM employees

WHERE employee_id = 100;

END;

7

The Problem

• Look at the code again. Wouldn’t it be easier to declare

one variable instead of eleven?

• As it did with cursors, %ROWTYPE allows us to declare a

variable as a record based on a particular table's structure.

• Each field or component within the record will have its

own name and data type based on the table's structure.

• You can refer to the whole record by its name

individual fields by their names.

and to

8

The Solution - Use a PL/SQL Record

• Use %ROWTYPE to declare a variable as a record based

on the structure of the employees table.

• Less code to write and nothing to change if columns are

added or dropped.

DECLARE

v_emp_record employees%ROWTYPE;

BEGIN

SELECT * INTO v_emp_record

FROM employees

WHERE employee_id = 100;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Email for ' || v_emp_record.first_name ||

' ' || v_emp_record.last_name || ' is ' || v_emp_record.email ||

'@oracle.com.');

END;

9

A Record Based on Another Record

You can use %ROWTYPE to declare a record based on

another record:

DECLARE

v_emp_record employees%ROWTYPE;

v_emp_copy_record v_emp_record%ROWTYPE;

BEGIN

SELECT * INTO v_emp_record

FROM employees

WHERE employee_id = 100;

v_emp_copy_record := v_emp_record;

v_emp_copy_record.salary := v_emp_record.salary * 1.2;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_emp_record.first_name ||

' ' || v_emp_record.last_name || ': Old Salary - ' ||

v_emp_record.salary || ', Proposed New Salary - ' ||

v_emp_copy_record.salary || '.');

END;

10

Defining Your Own Records

• What if you need data from a join of multiple tables?

• You can declare your own record structures containing any

fields you like.

• PL/SQL records:

– Must contain one or more components/fields of any scalar or

composite type

– Are not the same as rows in a database table

– Can be assigned initial values and can be defined as NOT NULL

– Can be components of other records (nested records).

11

Syntax for User-Defined Records

• Start with the TYPE keyword to define your record

structure.

• It must include at least one field and the fields may be

defined using scalar data types such as DATE,

VARCHAR2, or NUMBER, or using attributes such as

%TYPE and %ROWTYPE.

• After declaring the type, use the type_name to declare a

variable of that type.

TYPE type_name IS RECORD

(field_declaration[,field_declaration]...);

identifier

type_name;

12

User-Defined Records: Example 1

• First, declare/define the type and a variable of that type.

• Then use the variable and its components.

DECLARE

TYPE person_dept IS RECORD

(first_name

employees.first_name%TYPE,

last_name

employees.last_name%TYPE,

department_name departments.department_name%TYPE);

v_person_dept_rec person_dept;

BEGIN

SELECT e.first_name, e.last_name, d.department_name

INTO v_person_dept_rec

FROM employees e JOIN departments d

ON e.department_id = d.department_id

WHERE employee_id = 200;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_person_dept_rec.first_name ||

' ' || v_person_dept_rec.last_name || ' is in the ' ||

v_person_dept_rec.department_name || ' department.');

END;

13

User-Defined Records: Example 2

• Here we have two custom data types, one nested within

the other.

• How many fields can be addressed in v_emp_dept_rec?

DECLARE

TYPE dept_info_type IS RECORD

(department_id

departments.department_id%TYPE,

department_name

departments.department_name%TYPE)

TYPE emp_dept_type IS RECORD

employees.first_name%TYPE,

(first_name

employees.last_name%TYPE,

last_name

dept_info

dept_info_type);

v_emp_dept_rec

BEGIN

...

END;

emp_dept_type;

14

Declaring and Using Types and Records

• Types and records are composite structures that can be

declared anywhere that scalar variables can be declared

in anonymous blocks, procedures, functions, package

specifications (global), package bodies (local), triggers,

and so on.

• Their scope and visibility follow the same rules as for

scalar variables.

• For example, you can declare a type (and a record based

on the type) in an outer block and reference them within

an inner block.

15

Visibility and Scope of Types and Records

The type and the record declared in the outer block are

visible within the outer block and the inner block.

DECLARE -- outer block

TYPE employee_type IS RECORD

(first_name

employees.first_name%TYPE := 'Amy');

employee_type;

v_emp_rec_outer

BEGIN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_emp_rec_outer.first_name);

DECLARE -- inner block

v_emp_rec_inner

employee_type;

BEGIN

v_emp_rec_outer.first_name := 'Clara';

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_emp_rec_outer.first_name ||

' and ' || v_emp_rec_inner.first_name);

END;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_emp_rec_outer.first_name);

END;

16

Reference

Oracle Academy

PLSQL S6L1 User-Defined Records

Copyright © 2019, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

PL/SQL User's Guide and Reference, Release 9.0.1

Part No. A89856-01

Copyright © 1996, 2001, Oracle Corporation. All rights

reserved.

Primary Authors: Tom Portfolio, John Russell

INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME

• Distinguish between implicit and explicit cursors.

• Discuss the reasons for using explicit cursors.

• Declare and control explicit cursors.

• Use simple loops and cursor FOR loops to fetch data.

Context Areas and Cursors

• The Oracle server allocates a private memory area called a

context area to store the data processed by a SQL statement.

•

Every context area (and therefore every SQL statement) has

a cursor associated with it.

Cursor

Context Area

22

Context Areas and Cursors

• You can think of a cursor either as a label for the context

area, or as a pointer to the context area.

• In fact, a cursor is both of these items.

Cursor

Context Area

23

Implicit and Explicit Cursors

There are two types of cursors:

• Implicit cursors: Defined automatically by Oracle for all SQL

DML statements (INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE, and

MERGE), and for SELECT statements that return only one

row.

• Explicit cursors: Declared by the programmer for queries

that return more than one row.

– You can use explicit cursors to name a context area and

access its stored data.

24

Limitations of Implicit Cursors

• Programmers must think about the data that is possible as

well as the data that actually exists now.

• If there ever is more than one row in the EMPLOYEES

table, the SELECT statement below (without a WHERE

clause) will cause an error.

DECLARE

v_salary employees.salary%TYPE;

BEGIN

SELECT salary INTO v_salary

FROM employees;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(' Salary is : '||v_salary);

END;

ORA-01422:

exact fetch returns more than requested number of rows

25

Explicit Cursors

• With an explicit cursor, you can retrieve multiple rows

from a database table, have a pointer to each row that is

retrieved, and work on the rows one at a time.

• Reasons to use an explicit cursor:

– It is the only way in PL/SQL to retrieve more than one row

from a table.

– Each row is fetched by a separate program statement, giving

the programmer more control over the processing of the

rows.

26

Example of an Explicit Cursor

The following example uses an explicit cursor to display each

row from the departments table.

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_depts IS

SELECT department_id, department_name FROM departments;

v_department_id

departments.department_id%TYPE;

departments.department_name%TYPE;

v_department_name

BEGIN

OPEN cur_depts;

LOOP

FETCH cur_depts INTO v_department_id, v_department_name;

EXIT WHEN cur_depts%NOTFOUND;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_department_id||' '||v_department_name);

END LOOP;

CLOSE cur_depts;

END;

27

Explicit Cursor Operations

• The set of rows returned by a multiple-row query is called

the active set, and is stored in the context area.

• Its size is the number of rows that meet your query

criteria.

Table

Explicit Cursor

100

King

AD_PRES

101

Kochhar

AD_VP

102

De Haan

AD_VP

139

Seo

ST_CLERK

Active set

28

Explicit Cursor Operations

• Think of the context area (named by the cursor) as a box,

and the active set as the contents of the box.

• To get at the data, you must OPEN the box and FETCH

each row from the box one at a time.

• When finished, you must CLOSE the box.

Explicit Cursor

Table

100

King

AD_PRES

101

Kochhar

AD_VP

102

De Haan

AD_VP

139

Seo

ST_CLERK

Active set

29

Controlling Explicit Cursors

1

Open the cursor.

Cursor

pointer

2

Fetch each row,

one at a time.

3

Close the cursor.

Cursor

pointer

Cursor

pointer

30

Steps for Using Explicit Cursors

You first DECLARE a cursor, and then you use the OPEN,

FETCH, and CLOSE statements to control a cursor.

DECLARE

OPEN

FETCH

EXIT

Define the

cursor.

Fill the

cursor

active set

with data.

Retrieve the

current row

into

variables.

Test for

remaining

rows.

CLOSE

Release the

active set.

Return to

FETCH if

additional

row found.

31

Steps for Using Explicit Cursors

Now that you have a conceptual understanding of cursors,

review the steps to use them:

• DECLARE the cursor in the declarative section by naming it

and defining the SQL SELECT statement to be associated

with it.

• OPEN the cursor.

– This will populate the cursor's active set with the results of

the SELECT statement in the cursor's definition.

– The OPEN statement also positions the cursor pointer at the

first row.

32

Steps for Using Explicit Cursors

Now that you have a conceptual understanding of cursors,

review the steps to use them:

• FETCH each row from the active set and load the data into

variables.

– After each FETCH, the EXIT WHEN checks to see if the FETCH

reached the end of the active set resulting in a data NOTFOUND

condition.

– If the end of the active set was reached, the LOOP is exited.

• CLOSE the cursor.

– The CLOSE statement releases the active set of rows.

– It is now possible to reopen the cursor to establish a fresh

active set using a new OPEN statement.

33

Declaring the Cursor

When declaring the cursor:

• Do not include the INTO clause in the cursor declaration

because it appears later in the FETCH statement.

• If processing rows in a specific sequence is required, then

use the ORDER BY clause in the query.

• The cursor can be any valid SELECT statement, including

joins, subqueries, and so on.

• If a cursor declaration references any PL/SQL variables,

these variables must be declared before declaring the

cursor.

34

Syntax for Declaring the Cursor

• The active set of a cursor is determined by the SELECT

statement in the cursor declaration.

• Syntax:

CURSOR cursor_name IS

select_statement;

• In the syntax:

– cursor_name

– select_statement

Is a PL/SQL identifier

Is a SELECT statement without

an INTO clause

35

Declaring the Cursor Example 1

The cur_emps cursor is declared to retrieve the

employee_id and last_name columns of the employees

working in the department with a department_id of 30.

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_emps IS

SELECT employee_id, last_name FROM employees

WHERE department_id = 30;

...

36

Declaring the Cursor Example 2

• The cur_depts cursor is declared to retrieve all the

details for the departments with the location_id

1700.

• You want to fetch and process these rows in ascending

sequence by department_name.

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_depts IS

SELECT * FROM departments

WHERE location_id = 1700

ORDER BY department_name;

...

37

Declaring the Cursor Example 3

• A SELECT statement in a cursor declaration can include

joins, group functions, and subqueries.

• This example retrieves each department that has at least

two employees, giving the department name and number

of employees.

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_depts_emps IS

SELECT department_name, COUNT(*) AS how_many

FROM departments d, employees e

WHERE d.department_id = e.department_id

GROUP BY d.department_name

HAVING COUNT(*) > 1;

...

38

Opening the Cursor

• The OPEN statement executes the query associated with

the cursor, identifies the active set, and positions the

cursor pointer to the first row.

• The OPEN statement is included in the executable section

of the PL/SQL block.

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_emps IS

SELECT employee_id, last_name FROM employees

WHERE department_id = 30;

...

BEGIN

OPEN cur_emps;

...

39

Opening the Cursor

The OPEN statement performs the following operations:

• Allocates memory for a context area (creates the box to

hold the data)

• Executes the SELECT statement in the cursor declaration,

returning the results into the active set (fills the box with

the data)

• Positions the pointer to the first row

in the active set

40

Fetching Data from the Cursor

• The FETCH statement retrieves the rows from the cursor

one at a time.

• After each successful fetch, the cursor advances to the

next row in the active set.

DECLARE

CURSOR emp_cursor IS

SELECT employee_id, last_name FROM employees

WHERE department_id =10;

v_empno employees.employee_id%TYPE;

v_lname employees.last_name%TYPE;

BEGIN

OPEN emp_cursor;

FETCH emp_cursor INTO v_empno, v_lname;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE( v_empno ||' '||v_lname);

...

END;

41

Fetching Data from the Cursor

• Two variables, v_empno and v_lname, were declared to

hold the values fetched from the cursor.

DECLARE

CURSOR emp_cursor IS

SELECT employee_id, last_name FROM employees

WHERE department_id =10;

v_empno employees.employee_id%TYPE;

v_lname employees.last_name%TYPE;

BEGIN

OPEN emp_cursor;

FETCH emp_cursor INTO v_empno, v_lname;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE( v_empno ||' '||v_lname);

...

END;

42

Fetching Data from the Cursor

• The previous code successfully fetched the values from the

first row in the cursor into the variables.

• If there are other employees in department 50, you have

to use a loop as shown below to access and process each

row.

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_emps IS

SELECT employee_id, last_name FROM employees

WHERE department_id =50;

v_empno employees.employee_id%TYPE;

v_lname employees.last_name%TYPE;

BEGIN

OPEN cur_emps;

LOOP

FETCH cur_emps INTO v_empno, v_lname;

EXIT WHEN cur_emps%NOTFOUND;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE( v_empno ||' '||v_lname);

END LOOP; …

END;

43

Guidelines for Fetching Data From the

Cursor

Follow these guidelines when fetching data from the cursor:

• Include the same number of variables in the INTO clause

of the FETCH statement as columns in the SELECT

statement, and be sure that the data types are compatible.

• Match each variable to correspond to the columns position

in the cursor definition.

• Use %TYPE to ensure data types are compatible between

variable and table.

44

Guidelines for Fetching Data From the

Cursor

Follow these guidelines when fetching data from the cursor:

• Test to see whether the cursor contains rows.

• If a fetch acquires no values, then there are no rows to

process (or left to process) in the active set and no error is

recorded.

• You can use the %NOTFOUND cursor attribute to test for

the exit condition.

45

Fetching Data From the Cursor Example 1

What is wrong with this example?

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_emps IS

SELECT employee_id, last_name, salary FROM employees

WHERE department_id =30;

v_empno employees.employee_id%TYPE;

v_lname employees.last_name%TYPE;

v_sal

employees.salary%TYPE;

BEGIN

OPEN cur_emps;

LOOP

FETCH cur_emps INTO v_empno, v_lname;

EXIT WHEN cur_emps%NOTFOUND;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE( v_empno ||' '||v_lname);

END LOOP;

…

END;

46

Fetching Data From the Cursor Example 2

• There is only one employee in department 10.

• What happens when this example is executed?

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_emps IS

SELECT employee_id, last_name FROM employees

WHERE department_id =10;

v_empno

employees.employee_id%TYPE;

v_lname

employees.last_name%TYPE;

BEGIN

OPEN cur_emps;

LOOP

FETCH cur_emps INTO v_empno, v_lname;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_empno || ' ' || v_lname);

END LOOP;

…

END;

47

Closing the Cursor

• The CLOSE statement disables the cursor, releases the

context area, and undefines the active set.

• You should close the cursor after completing the

processing of the FETCH statement.

...

LOOP

FETCH cur_emps INTO v_empno, v_lname;

EXIT WHEN cur_emps%NOTFOUND;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_empno || ' ' ||

v_lname);

END LOOP;

CLOSE cur_emps;

END;

48

Closing the Cursor

• You can reopen the cursor later if required.

• Think of CLOSE as closing and emptying the box, so you

can no longer FETCH its contents.

...

LOOP

FETCH cur_emps INTO v_empno, v_lname;

EXIT WHEN cur_emps%NOTFOUND;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_empno || ' ' ||

v_lname);

END LOOP;

CLOSE cur_emps;

END;

49

Guidelines for Closing the Cursor

Follow these guidelines when closing the cursor:

• A cursor can be reopened only if it is closed.

• If you attempt to fetch data from a cursor after it has been

closed, then an INVALID_CURSOR exception is raised.

• If you later reopen the cursor, the associated SELECT

statement is re-executed to re-populate the context area

with the most recent data from the database.

50

Putting It All Together

Now, when looking at an explicit cursor, you should be able

to identify the cursor-related keywords and explain what

each statement is doing.

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_depts IS

SELECT department_id, department_name FROM departments

v_department_id

departments.department_id%TYPE;

v_department_name

departments.department_name%TYPE;

BEGIN

OPEN cur_depts;

LOOP

FETCH cur_depts INTO v_department_id, v_department_name;

EXIT WHEN cur_depts%NOTFOUND;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_department_id||' '||v_department_name);

END LOOP;

CLOSE cur_depts;

END;

51

Explicit Cursor Attributes

• As with implicit cursors, there are several attributes for

obtaining status information about an explicit cursor.

• When appended to the cursor variable name, these

attributes return useful information about the execution of

a cursor manipulation statement.

Attribute

Type

Description

%ISOPEN

Boolean

Evaluates to TRUE if the cursor is open.

%NOTFOUND

Boolean

Evaluates to TRUE if the most recent fetch did not return

a row.

%FOUND

Boolean

Evaluates to TRUE if the most recent fetch returned a

row; opposite of %NOTFOUND.

%ROWCOUNT

Number

Evaluates to the total number of rows FETCHed so far.

53

%ISOPEN Attribute

• You can fetch rows only when the cursor is open.

• Use the %ISOPEN cursor attribute before performing a

fetch to test whether the cursor is open.

• %ISOPEN returns the status of the cursor: TRUE if open

and FALSE if not.

• Example:

IF NOT cur_emps%ISOPEN THEN

OPEN cur_emps;

END IF;

LOOP

FETCH cur_emps...

54

%ROWCOUNT and %NOTFOUND

Attributes

• Usually the %ROWCOUNT and %NOTFOUND attributes

are used in a loop to determine when to exit the loop.

• Use the %ROWCOUNT cursor attribute for the following:

– To process an exact number of rows

– To count the number of rows fetched so far in a loop and/or

determine when to exit the loop

55

%ROWCOUNT and %NOTFOUND

Attributes

Use the %NOTFOUND cursor attribute for the following:

• To determine whether the query found any rows matching

your criteria

• To determine when to exit the loop

56

Example of %ROWCOUNT and

%NOTFOUND

This example shows how you can use %ROWCOUNT and

%NOTFOUND attributes for exit conditions in a loop.

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_emps IS

SELECT employee_id, last_name FROM employees;

v_emp_record

cur_emps%ROWTYPE;

BEGIN

OPEN cur_emps;

LOOP

FETCH cur_emps INTO v_emp_record;

EXIT WHEN cur_emps%ROWCOUNT > 10 OR cur_emps%NOTFOUND;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_emp_record.employee_id || ' '

|| v_emp_record.last_name);

END LOOP;

CLOSE cur_emps;

END;

57

Explicit Cursor Attributes in SQL Statements

• You cannot use an explicit cursor attribute directly in an

SQL statement.

• The following code returns an error:

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_emps IS

SELECT employee_id, salary

FROM employees

ORDER BY SALARY DESC;

v_emp_record

cur_emps%ROWTYPE;

v_count

NUMBER;

BEGIN

OPEN cur_emps;

LOOP

FETCH cur_emps INTO v_emp_record;

EXIT WHEN cur_emps%NOTFOUND;

INSERT INTO top_paid_emps (employee_id, rank, salary)

VALUES

(v_emp_record.employee_id, cur_emps%ROWCOUNT, v_emp_record.salary);

...

58

Explicit Cursor Attributes in SQL Statements

• To avoid the error on the previous slide,we would copy the

cursor attribute value to a variable, then use the variable in the

SQL statement:

Cursor FOR Loops

• A cursor FOR loop processes rows in an explicit cursor.

• It is a shortcut because the cursor is opened, a row is

fetched once for each iteration in the loop, the loop exits

when the last row is processed, and the cursor is closed

automatically.

• The loop itself is terminated automatically at the end of

the iteration when the last row has been fetched.

• Syntax:

FOR record_name IN cursor_name LOOP

statement1;

statement2;

. . .

END LOOP;

61

Cursor FOR Loops

In the syntax:

• record_name

• cursor_name

Is the name of the implicitly declared

record (as cursor_name%ROWTYPE)

Is a PL/SQL identifier for a previously

declared cursor

FOR record_name IN cursor_name LOOP

statement1;

statement2;

. . .

END LOOP;

62

Cursor FOR Loops

• You can simplify your coding by using a cursor FOR loop

instead of the OPEN, FETCH, and CLOSE statements.

• A cursor FOR loop implicitly declares its loop counter as a

record that represents a row FETCHed from the database.

• A cursor FOR loop:

–OPENs a cursor.

– Repeatedly FETCHes rows of values from the active set

into fields in the record.

– CLOSEs the cursor when all rows have been processed.

Cursor FOR Loops

• Note: v_emp_record is the record that is implicitly

declared.

• You can access the fetched data with this implicit record as

shown below.

64

Cursor FOR Loops

• No variables are declared to hold the fetched data and no

INTO clause is required.

• OPEN and CLOSE statements are not required, they happen

automatically in this syntax.

Cursor FOR Loops

• There is no need to declare the variable v_emp_rec in the

declarative section. The syntax "FOR v_emp_rec IN …"

implicitly defines v_emp_rec.

• The scope of the implicit record is restricted to the loop, so

you cannot reference the fetched data outside the loop.

Cursor FOR Loops

• Compare the cursor FOR loop (on the left) with the cursor

code you learned in the previous lesson.

• The two forms of the code are logically identical to each

other and produce exactly the same results.

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_emps IS

SELECT employee_id, last_name

FROM employees

WHERE department_id = 50;

BEGIN

FOR v_emp_rec IN cur_emps LOOP

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(…);

END LOOP;

END;

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_emps IS

SELECT employee_id, last_name

FROM employees

WHERE department_id = 50;

v_emp_rec cur_emps%ROWTYPE;

BEGIN

OPEN cur_emps;

LOOP

FETCH cur_emps INTO v_emp_rec;

EXIT WHEN cur_emps%NOTFOUND;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(…);

END LOOP;

CLOSE cur_emps;

END;

67

Guidelines for Cursor FOR Loops

Guidelines:

• Do not declare the record that controls the loop because it

is declared implicitly.

• The scope of the implicit record is restricted to the loop, so

you cannot reference the record outside the loop.

• You can access fetched data using

record_name.column_name.

68

Testing Cursor Attributes

• You can still test cursor attributes, such as %ROWCOUNT.

• This example exits from the loop after five rows have been

fetched and processed.

• The cursor is still closed automatically.

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_emps IS

SELECT employee_id, last_name

FROM employees;

BEGIN

FOR v_emp_record IN cur_emps LOOP

EXIT WHEN cur_emps%ROWCOUNT > 5;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_emp_record.employee_id || ' ' ||

v_emp_record.last_name);

END LOOP;

END;

69

Cursor FOR Loops Using Subqueries

• You can go one step further. You don’t have to declare the

cursor at all!

• Instead, you can specify the SELECT on which the cursor

is based directly in the FOR loop.

• The advantage of this is the cursor definition is contained

in a single FOR … statement.

• In complex code with lots of cursors, this simplification

makes code maintenance easier and quicker.

• The downside is you can't reference cursor attributes.

70

Cursor FOR Loops Using Subqueries:

Example

The SELECT clause in the FOR statement is technically a

subquery, so you must enclose it in parentheses.

BEGIN

FOR v_emp_record IN (SELECT employee_id, last_name

FROM employees WHERE department_id = 50)

LOOP

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_emp_record.employee_id || ' '

|| v_emp_record.last_name);

END LOOP;

END;

71

Cursor FOR Loops Using Subqueries

• Again, compare these two forms of code.

• They are logically identical, but which one would you

rather write – especially if you hate typing!

BEGIN

FOR v_dept_rec IN (SELECT *

FROM departments) LOOP

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(…);

END LOOP;

END;

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_depts IS

SELECT * FROM departments;

v_dept_rec

cur_depts%ROWTYPE;

BEGIN

OPEN cur_depts;

LOOP

FETCH cur_depts INTO

v_dept_rec;

EXIT WHEN

cur_depts%NOTFOUND;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(…);

END LOOP;

CLOSE cur_depts;

END;

72

Reference

Oracle Academy

PLSQL S5L1 Introduction to Explicit Cursors

PLSQL S5L2 Using Explicit Cursor Attributes

PLSQL S5L3 Cursor FOR Loops

Copyright © 2019, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

PL/SQL User's Guide and Reference, Release 9.0.1

Part No. A89856-01

Copyright © 1996, 2001, Oracle Corporation. All rights

reserved.

Primary Authors: Tom Portfolio, John Russell

INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME

• Declare and use cursors with parameters.

• Lock rows with the FOR UPDATE clause.

Cursors with Parameters

• A parameter is a variable whose name is used in a cursor

declaration.

• When the cursor is opened, the parameter value is passed

to the Oracle server, which uses it to decide which rows to

retrieve into the active set of the cursor.

78

Cursors with Parameters

• This means that you can open and close an explicit cursor

several times in a block, or in different executions of the

same block, returning a different active set on each

occasion.

• Consider an example where you pass a location_id to a

cursor and it returns the names of the departments at that

location.

79

Cursors with Parameters: Example

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_country (p_region_id NUMBER) IS

SELECT country_id, country_name

FROM countries

WHERE region_id = p_region_id;

v_country_record

cur_country%ROWTYPE;

BEGIN

Change to whichever

OPEN cur_country (5);

region is required.

LOOP

.

FETCH cur_country INTO v_country_record;

EXIT WHEN cur_country%NOTFOUND;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_country_record.country_id || ' '

|| v_country_record.country_name);

END LOOP;

CLOSE cur_country;

END;

80

Defining Cursors with Parameters Syntax

• Each parameter named in the cursor declaration must

have a corresponding value in the OPEN statement.

• Parameter data types are the same as those for scalar

variables, but you do not give them sizes.

• The parameter names are used in the WHERE clause of the

cursor SELECT statement.

CURSOR cursor_name

[(parameter_name datatype, ...)]

IS

select_statement;

81

Defining Cursors with Parameters Syntax

In the syntax:

• cursor_name Is a PL/SQL identifier for the declared

cursor

• parameter_name Is the name of a parameter

• datatype Is the scalar data type of the parameter

• select_statement Is a SELECT statement without

the INTO clause

CURSOR cursor_name

[(parameter_name datatype, ...)]

IS

select_statement;

82

Opening Cursors with Parameters

The following is the syntax for opening a cursor with

parameters:

OPEN cursor_name(parameter_value1, parameter_value2, ...);

83

Cursors with Parameters

• You pass parameter values to a cursor when the cursor is

opened.

• Therefore you can open a single explicit cursor several

times and fetch a different active set each time.

• In the following example, a cursor is opened several times.

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_countries (p_region_id NUMBER) IS

SELECT country_id, country_name FROM countries

WHERE region_id = p_region_id;

v_country_record

c_countries%ROWTYPE;

BEGIN

OPEN cur_countries (5);

Open the cursor again and

...

CLOSE cur_countries;

return a different active set.

OPEN cur_countries (145);

...

84

Another Example of a Cursor with a Parameter

DECLARE

v_deptid

employees.department_id%TYPE;

CURSOR cur_emps (p_deptid NUMBER) IS

SELECT employee_id, salary

FROM employees

WHERE department_id = p_deptid;

v_emp_rec

cur_emps%ROWTYPE;

BEGIN

SELECT MAX(department_id) INTO v_deptid

FROM employees;

OPEN cur_emps(v_deptid);

LOOP

FETCH cur_emps INTO v_emp_rec;

EXIT WHEN cur_emps%NOTFOUND;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_emp_rec.employee_id || '

|| v_emp_rec.salary);

END LOOP;

CLOSE cur_emps;

END;

'

85

Cursor FOR Loops wıth a Parameter

We can use a cursor FOR loop if needed:

DECLARE

CURSOR

cur_emps (p_deptno NUMBER) IS

SELECT employee_id, last_name

FROM

employees

WHERE

department_id = p_deptno;

BEGIN

FOR v_emp_record IN cur_emps(10) LOOP

...

END LOOP;

END;

86

Cursors with Multiple Parameters: Example 1

In the following example, a cursor is declared and is called

with two parameters:

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_countries (p_region_id NUMBER, p_population NUMBER) IS

SELECT country_id, country_name, population

FROM

countries

WHERE

region_id = p_region_id

OR

population > p_population;

BEGIN

FOR v_country_record IN cur_countries(145,10000000) LOOP

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_country_record.country_id ||' '

|| v_country_record. country_name||' '

|| v_country_record.population);

END LOOP;

END;

87

Cursors with Multiple Parameters: Example 2

This cursor fetches all IT Programmers who earn more than

$10,000.00

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_emps (p_job VARCHAR2, p_salary NUMBER) IS

SELECT employee_id, last_name

FROM

employees

WHERE

job_id = p_job

AND

salary > p_salary;

BEGIN

FOR v_emp_record IN cur_emps('IT_PROG', 10000) LOOP

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(v_emp_record.employee_id ||' '

|| v_emp_record.last_name);

END LOOP;

END;

88

89

Declaring a Cursor with the FOR UPDATE

Syntax

• When we declare a cursor FOR UPDATE, each row is

locked as we open the cursor.

• This prevents other users from modifying the rows while

our cursor is open.

• It also allows us to modify the rows ourselves using a …

WHERE CURRENT OF … clause.

CURSOR cursor_name IS

SELECT

... FROM ...

FOR UPDATE [OF column_reference][NOWAIT | WAIT n];

• This does not prevent other users from reading the rows.

90

Declaring a Cursor with the FOR UPDATE

Clause

• column_reference is a column in the table whose

rows we need to lock.

CURSOR cursor_name IS

SELECT

... FROM ...

FOR UPDATE [OF column_reference][NOWAIT | WAIT n];

• If the rows have already been locked by another session:

– NOWAIT returns an Oracle server error immediately

– WAIT n waits for n seconds, and returns an Oracle server

error if the other session is still locking the rows at the end of

that time.

91

NOWAIT Keyword in the FOR UPDATE

Clause Example

• The optional NOWAIT keyword tells the Oracle server not

to wait if any of the requested rows have already been

locked by another user.

• Control is immediately returned to your program so that it

can do other work before trying again to acquire the lock.

• If you omit the NOWAIT keyword, then the Oracle server

waits indefinitely until the rows are available.

DECLARE

CURSOR cur_emps IS

SELECT employee_id, last_name FROM employees

WHERE department_id = 80 FOR UPDATE NOWAIT;

...

92

NOWAIT Keyword in the FOR UPDATE

Clause

• If the rows are already locked by another session and you

have specified NOWAIT, then opening the cursor will

result in an error.

• You can try to open the cursor later.

• You can use WAIT n instead of NOWAIT and specify the

number of seconds to wait and check whether the rows

are unlocked.