Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Oscillations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Travelling waves . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.1

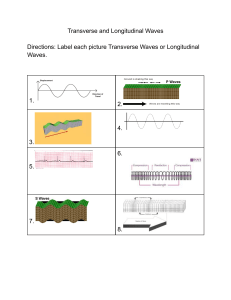

Transverse waves . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.2

Longitudinal waves . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Doppler effect . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The principle of linear superposition . . . . . . . .

Constructive and destructive interference . . . . .

Beats . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Standing waves . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7.1

Speed of a transverse wave on a string . .

7.2

Standing waves on a stretched string . . .

7.3

Standing sound waves in pipes: open pipe .

7.4

Standing sound waves in pipes: closed pipe

Resonance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The electromagnetic spectrum . . . . . . . . . . .

i

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

1

1

2

3

4

6

6

7

8

9

12

13

13

14

15

List of Examples

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Speed of sound at different temperatures. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Apparent frequency of a moving siren. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Interference due to two sound sources of the same frequency. .

Speed of a ship from the beat frequency and the Doppler effect.

Air temperature from data of a stationary wave system. . . . .

Mass of a stretched string. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Speed of a transverse wave on a string. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Harmonic of a transverse wave on a string. . . . . . . . . . . .

Length of pipe required to produce a specific frequency. . . . . .

The wavelength of an electromagnetic wave. . . . . . . . . . .

ii

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

4

5

7

8

9

11

11

12

13

16

Vibrations and Waves

1

Oscillations

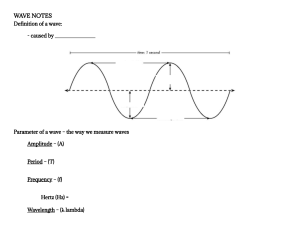

Any motion that repeats itself in equal time intervals is said to be periodic or cyclic. Examples

of periodic motion include the orbits of the moon and planets, the swing of a pendulum, or the

movement of air particles as a sound wave passes. Periodic motion can be described in terms

of sine functions and is therefore also referred to as harmonic motion.

An oscillating or vibrating particle moves to and fro about some fixed point or equilibrium

position. The displacement is the distance of the oscillating particle from the equilibrium

position. The period is the time interval for one complete cycle and the number of cycles per

unit time is the frequency. Thus

f =

1

.

T

(1)

The Greek letter ν (nu) is often used as the symbol for frequency instead of f . The unit of

frequency is the hertz (Hz). 1 Hz = 1 s−1 .

A common type of periodic motion that can be described in a simple way mathematically

is simple harmonic motion. In simple harmonic motion the displacement of the oscillating

particle varies sinusoidally with time (the acceleration is proportional to the displacement and

in the opposite direction).

2

Travelling waves

Examples of travelling (or progressive) wave phenomena abound in nature. Music is a result of

sound waves travelling through the air and setting your eardrum vibrating. Surfers ride water

waves and everything we see is a result of light waves reflecting from the objects we look at.

Waves are produced by vibrations or oscillations. A mechanical wave originates in the

vibration of some portion of an elastic medium. The energy of the vibration is transmitted to

adjacent layers of the medium thus producing a wave that travels through the medium. Water

waves, sound waves or a wave moving along a stretched string are all examples of mechanical

waves. Light waves and radio waves are electromagnetic waves (see Section 9). These do

not require a medium through which to propagate. Light from the stars travels many years

through the near vacuum of interstellar space to reach us.

If the oscillation producing a wave is perpendicular to the direction of motion of the wave,

like a wave moving along a stretched string, it is called a transverse wave. If the oscillation is in

the same direction as the resulting wave, for example a sound wave, it is called a longitudinal

wave.

1

2.1

Transverse waves

As an example of a transverse wave we consider a wave produced in a stretched string by an

oscillating mass on a spring, as in the Figure 1.

crest

wavelength

spring

oscillating

mass

trough

Figure 1: Transverse wave in a stretched string.

The period (T ) is the time for 1 cycle to pass any point.

In the example above, the period is the time for the mass on the spring to bob up and down

once.

One wavelength (λ) is the shortest distance between particles that are at the same stage of

vibration.

The amplitude is the maximum displacement from the equilibrium position.

amplitude

λ

Figure 2: One cycle of a wave.

During one cycle, the wave travels a distance λ. If f oscillations occur per second, then the

distance travelled by the wave in 1 second (the speed of the wave) is given by f × λ. Hence

v =fλ .

(2)

The speed v of a wave depends on the medium through which the wave is travelling and the

frequency f depends on the source. v is measured in m s−1 , f in s−1 or Hz and λ in metres.

2

2.2

Longitudinal waves

If the vibrating elements producing a mechanical wave oscillate in the direction of the propagation of the wave, as is the case for sound waves, then the wave is known as a longitudinal

wave.

P

listener

mean

position

Figure 3: Representation of a sound wave through air.

The air between a vibrating tuning fork and a listener can be regarded as made up of thin

layers of molecules. As the prong (P) moves to the right (see Figure 3) it presses on the

adjacent layer, which in turn presses on the next and so on. As P moves to the left, the layers

move successively back. Regions of compression and rarefaction are thus transferred through

the air to the listener.

Each layer of air vibrates about a mean position and vibrates along the direction of propagation. At a particular instant a graph of the displacement of each layer plotted against its

mean position might be as in the lower portion of Figure 3.

For both transverse and longitudinal waves, we can draw displacement–position graphs for

any particular instant (often called simply displacement curves). These plot the instantaneous

displacement of each ‘particle’ (or layer) against its mean position.

The speed of sound depends on the medium through which the sound wave is propagating.

Some values for the speed of sound are listed in Table 1 Because sound travels more slowly than

Medium (at 0 ◦C)

Speed (m s−1 )

AIR

HYDROGEN

WATER

SEA WATER

IRON

331

1280

1480

1520

5100

Table 1: Some values for the speed of sound in different media.

light, thunder can be heard some seconds after lightning is observed. Sound takes approximately

3 seconds to travel 1 km in air.

The speed of sound in a gas is (a) independent of the gas pressure and (b) proportional to

the square root of the absolute temperature. (See later notes on Heat for an explanation of

3

absolute temperature.)

V ∝

√

T ,

(3)

where T is the absolute temperature in degrees kelvin.

Example 1: Speed of sound at different temperatures.

If the speed of sound in air at 0 ◦C is 331 m s−1 , what will it be at 15 ◦C?

Solution:

From Equation (3) we may relate the speed at different temperatures. Thus, converting

degrees Celsius to degrees kelvin,

r

V15

273 + 15

=

,

V0

273 + 0

which gives

V15 = 331 ×

3

r

288

= 340 m s−1 .

273

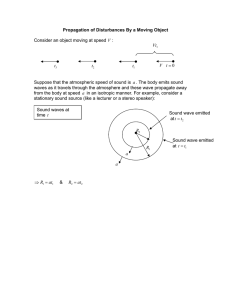

The Doppler effect

The Doppler effect is the apparent change in frequency of the wave emitted by a source

resulting from the motion of either the source, the observer, or both. It occurs for both sound

waves and light waves. Examples of the Doppler effect are the drop in apparent pitch of a

train whistle as it passes, or the shift in observed frequency of light radiated from a star which

is moving away from the earth.

An observer moving with speed vo towards a stationary source of waves intercepts more

waves per second than when stationary, so the apparent frequency f ′ is higher than the actual

frequency f . It can be shown that

f′ =

V + vo

· f,

V

(4)

where V is the speed of the wave. Note that the sign of vo changes if the observer is moving

away from the source.

If on the other hand a source is moving towards a stationary observer with speed vs ,

the waves sent out per second occupy a shorter distance (they are more ‘crowded’ together).

Thus the effective wavelength is shortened, causing a corresponding increase in the apparent

frequency f ′ . It can be shown that

f′ =

V

· f.

V − vs

(5)

Again the sign of vs changes if the source is moving away from the observer.

Thus for a source emitting a sound approaching an observer, the apparent frequency heard

by the observer is higher then the actual frequency, but once it has passed and is moving away,

the frequency is lower than the actual frequency.

4

S′

b

b

b

b

S

b

vs

b

P

b

Observer

Figure 4: Doppler effect caused by a source S moving towards an observer.

If both the observer and the source are moving towards each other, then

f ′′ =

V + vo

· f.

V − vs

(6)

Equation (4) and Equation (5) are special cases of the general expression given by Equation (6)

and can be obtained by setting vs = 0 and vo = 0 respectively in Equation (6).

Example 2: Apparent frequency of a moving siren.

A high-speed train is travelling at a speed of 45 m s−1 when the driver sounds the 415 Hz

warning siren. If the speed of sound is 343 m s−1 , calculate the frequency and wavelength of

the sound as perceived by a person standing at a crossing, when the train is (a) approaching

and (b) leaving the crossing.

Solution:

Since the train is moving and the observer is stationary, we use Equation (4) (or Equation (6) with vo = 0).

(a) For the approaching train, the apparent frequency f ′ is higher than the true value.

f′ =

V

343

·f =

· 415 = 478 Hz.

V − vs

343 − 45

The corresponding wavelength

λ′ =

V

343

=

= 0.718 m.

′

f

478

(b) After the train has passed, the apparent frequency f ′ is lower than the true value (the

source is moving away), hence

f′ =

V

343

·f =

· 415 = 367 Hz.

V + vs

343 + 45

The corresponding wavelength

λ′ =

343

V

=

= 0.935 m.

f′

367

5

4

The principle of linear superposition

In most situations, many waves are present at a certain place at the same time. For instance

several people talking at once or the music created by several instruments playing simultaneously. The principle of linear superposition enables us to describe the resultant waveform due

to the individual waves present.

Principle of linear superposition

When two or more waves are present simultaneously at the same place, the resultant disturbance is the sum of the disturbances of the individual waves.

5

Constructive and destructive interference

The interaction of individual waves with each other is known as interference. When the peaks

and troughs of two waves coincide as in Figure 5a, the waves are said to be exactly in phase.

The resultant waveform obtained by adding waves that are in phase is a wave of amplitude

equal to the sum of the amplitudes of the individual waves. Waves that are in phase exhibit

constructive interference.

+

=

+

(a) Constructive interference

=

(b) Destructive interference

Figure 5: Two waves of equal amplitude and wavelength interfere (a) constructively when they

are in phase and (b) destructively when they are out of phase.

When the peaks of one wave coincide with the troughs of another wave as in Figure 5b,

the waves are said to be exactly out of phase. The resultant waveform obtained by adding

waves that are out of phase is a wave of amplitude equal to the difference of the amplitudes

of the individual waves. Waves that are out of phase exhibit destructive interference. If the

amplitudes of two waves which are exactly out of phase are equal, then the waves will cancel.

In the case of two sound waves, no sound will be heard.

If the sound waves from two adjacent loudspeakers (which are fed from the same oscillator)

are mixed, interference occurs.

At any point P, if the path difference S2 P − S1 P between each speaker and P is a whole

number of wavelengths, the crests (and troughs) at P will coincide and we get reinforcement

(constructive interference). If on the other hand the path difference is a whole number of

wavelengths plus half a wavelength, then the crests from one speaker will coincide with the

troughs from the other speaker and we get cancellation (destructive interference).

For constructive interference

S2 P − S1 P = mλ

(m = 0, 1, 2, . . .) ,

6

(7)

and for destructive interference,

S2 P − S1 P = (m + 21 )λ

(m = 0, 1, 2, . . .) .

(8)

Example 3: Interference due to two sound sources of the same frequency.

Two speakers, A and B, both produce a note of 850 Hz. If the speakers are placed 5.0 m apart,

determine whether a listener standing 12 m in front of speaker A, and perpendicular to the line

joining the speakers, will hear a maximum or a minimum. (Take the speed of sound in air as

340 m s−1 .)

12 m

A

b

P

5m

b

B

b

Solution:

To determine whether constructive or destructive interference will occur, we need to determine the path difference BP − AP, and calculate if this is a whole number of wavelengths,

or a whole number plus a half number of wavelengths. BX = 13 m since △BAP is a right

angled triangle. The path difference is therefore BP − AP = 1 m. The wavelength may be

obtained from Equation eq:wav-speed:

λ=

340

v

=

= 0.4 m.

f

850

The path difference is therefore 2 12 times the wavelength, hence destructive interference

occurs and a minimum will be heard.

6

Beats

Suppose two sources of sound have nearly equal frequency. The resultant effect at any point

due to the waves can be obtained by adding the two separate effects due to each source.

At a certain moment, the two waves will be in step as they reach the ear and a loud sound

is heard. A short time later they are out of step and a minimum sound is heard. The resulting

sound rises and falls in intensity which is known as the beats effect (see Figure 6).

Suppose two people walk side by side and that one takes 60 steps per minute while the

other takes 59. They will be in step once per minute. If the second person takes 58 steps

per minute, she will take 29 steps while the other takes 30 steps and they will now be in step

twice per minute. The number of times the two people get into step will equal the difference

between the frequencies of their steps. Similarly for two sources of sound having frequencies

f1 and f2 ,

beat frequency f = f1 − f2 .

7

(9)

y

(b)

t

y

(a)

t

Figure 6: The beats phenomenon. Two waves of slightly different frequencies (a), combine to

give a wave whose envelope (dashed line) varies periodically with time (b).

Example 4: Speed of a ship from the beat frequency and the Doppler effect.

The fog horn of ships A and B have frequencies of 200 Hz and 198 Hz respectively. If ship A is

moving directly towards ship B which is stationary, what is its speed when the captain of ship

B hears a beat frequency of 6 Hz? (Take the velocity of sound in air as 340 m s−1 .)

Solution:

The captain of ship B hears the true frequency of his own foghorn (fB ) and the (Doppler)

shifted frequency of ship A (fA′ ). He therefore hears a beat frequency fbeat = |fA′ −fB | = 6 Hz.

Now fA′ > fA > fB , hence

fA′ = fB + fbeat = 198 + 6 = 204 Hz.

Ship B (the observer) is stationary, hence vo = 0, and from Equation (5)

fA′ =

V

340

· fA =

· 200,

V − vs

340 − vs

which gives

vs = 6.7 m s−1 .

7

Standing waves

Standing (or stationary) waves occur when a wave is reflected. Both transverse and longitudinal waves can form standing waves. Consider the displacement curves of a transverse and

longitudinal wave:

In each case, to obtain a resultant displacement curve, a forward and reflected wave are

added. The resultant displacement for both waves at O is zero. In the case of the string, point

O is held fixed by the clamp. In the case of the sound wave, the layer of air adjacent to the

wall cannot move.

Figure 7 shows the displacement curves for forward and reflected waves (dashed lines). The

sum in each case is shown as a solid line. Notice that there are places where the resultant

displacement is always zero. These points are called nodes (marked with an N in Figure 7).

8

(a) Transverse wave along a string

b

(b) Sound wave

O

b

O

Suppose a sound wave strikes a wall at

O. Again a reflection occurs (as in an

echo).

Suppose a string is clamped at O. The

reaction of the clamp on the string

varies in a simple harmonic way and

propagates its own wave back along the

string producing a reflected wave.

Successive nodes are spaced at distances equal to half the wavelength. The antinodes are

midway between the nodes. At the antinodes, the resultant displacement is a maximum.

At the point where the waves are reflected (at the right of Figure 7) the displacement of

the forward waves is equal and opposite to the displacement of the reflected wave. There is

effectively a path length change of half a wavelength on reflection.

Example 5: Air temperature from data of a stationary wave system.

A tuning fork of frequency 1 kHz is used to set up a stationary wave system in which successive

nodes are 17.5 cm apart. Calculate the air temperature (take the velocity of sound in air at

27 ◦C as 347 m s−1 ).

Solution:

The wavelength of the system is twice the distance between the nodes, hence

λ = 2 × 17.5 = 35 cm.

The velocity of the sound wave can now be determined from Equation (2):

V = f λ = 1 × 103 s−1 × 0.35 m = 350 m s−1 .

The temperature is found from Equation (3):

VT

350

=

=

V27

347

r

T

,

273 + 27

which gives

T = 300 ×

7.1

350

347

2

= 305 K = 30.5 ◦C.

Speed of a transverse wave on a string

We would expect the speed V to be larger if the tension T in a string is larger and smaller if

the mass per unit length µ is larger. It turns out that

s

T

,

(10)

V =

µ

9

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

Figure 7: Method of adding two waves of equal lengths and equal amplitudes travelling in

opposite directions to produce a standing wave.

10

where µ is the mass per unit length of the string

µ=

m

.

ℓ

(11)

When a musician tunes a stringed instrument like a guitar, she is changing the tension of

the strings. From Equation (10) it is clear that increasing the tension increases the speed.

Since the speed of a wave is proportional to the frequency, increasing the tension increases

the frequency and hence the pitch of a note. The lowest notes on a stringed instrument are

produced by the thickest strings for which µ is larger. From Equation (10) it is clear that for

a greater mass per unit length the speed, and hence the frequency, is smaller.

Example 6: Mass of a stretched string.

A length of string is stretched between two points 80 cm apart. The tension in the string is

20 N and the speed of a transverse wave on the string is 80 m s−1 . Determine the mass of the

string.

Solution:

The mass per unit length is obtained from Equation (10):

µ=

20

T

= 2 = 3.125 × 10−3 kg m−1 .

2

V

80

We obtain the mass from Equation (11):

m = µℓ = 3.125 × 10−3 × 0.8 = 0.0025 kg.

Example 7: Speed of a transverse wave on a string.

The high E string of a guitar has a mass per unit length of 3.851 × 10−4 kg m−1 and is under a

tension of 70.266 N. Calculate the fundamental frequency of this string if the length is 648 mm.

Solution:

From Equation (10) we can determine the speed of the wave on the string:

V =

s

T

=

µ

r

70.266

= 427.2 m s−1 .

3.851 × 10−4

The fundamental frequency on a stretched string corresponds to half the wavelength, hence

λ = 2 × 0.648 = 1.296 m.

The frequency produced by this string may now be found from Equation (2):

f =

427.2

V

=

= 329.6 Hz.

λ

1.296

11

L

λ1

2

s

V

V

1

T

f1 =

=

=

λ1

2L

2L µ

L=

First harmonic (fundamental mode of vibration)

Second harmonic (first

overtone) f2 = 2f1

L = λ2

s

1 T

V

=

f2 =

λ2

L µ

Third harmonic (second

overtone) f3 = 3f1

3λ3

2

s

T

3

V

=

f3 =

λ3

2L µ

L=

Figure 8: Various modes of vibration for a stretched string fixed at both ends.

7.2

Standing waves on a stretched string

Various modes of vibration are possible for a stretched string fixed at both ends. The essential

requirement to produce a standing wave is that there should be a node at each end. In general,

nλn

and

for the nth harmonic, L =

2

s

n

T

fn =

for

n = 1, 2, 3, . . . .

(12)

2L µ

Example 8: Harmonic of a transverse wave on a string.

A transverse wave of frequency 120 Hz is applied to a string of length 0.450 m which is fixed

at both ends. If the propagation speed of the wave is 36.0 m s−1 , (a) at what harmonic is the

string vibrating and (b) How many antinodes are there?

Solution:

(a) To determine at which harmonic the string is vibrating, we need to compare the

wavelength to the length of the string. The wavelength is

λ=

36.0

V

=

= 0.3 m.

f

120

We know that L = nλ/2, hence

n=

2L

2 × 0.45

=

=3

λ

0.3

The string is therefore vibrating at the third harmonic – see Figure 8.

(b) The third harmonic corresponds to three antinodes.

12

7.3

Standing sound waves in pipes: open pipe

When a sound wave travels through a hollow pipe, standing waves are set up. This phenomenon

has long been used for making musical sounds. Flutes, organ pipes and didgeridoos all produce

sounds in a similar way.

L

First harmonic

(Fundamental mode

of vibration)

P

S

R

A

N

A

Q

λ1

2

V

f1 =

2L

L=

Second harmonic (First

overtone) f2 = 2f1

L = λ2

V

f2 =

L

Third harmonic (Second

overtone) f3 = 3f1

3λ3

2

3V

f3 =

2L

L=

Figure 9: Various modes of vibration for a sound wave in an open pipe.

In general, for the nth harmonic,

fn =

nV

2L

n = 1, 2, 3, . . . .

for

(13)

A sound wave travelling through a pipe which is open at both ends is partially reflected

at the ends. Since there is motion at the end of the pipe, the end point is an antinode. In

Figure 9, the resultant displacement curves for a standing wave in a hollow pipe are shown for

the first three harmonics. For clarity the resultant for a vibration at a particular moment (PQ)

as well as the resultant for a moment half a vibration later (RS) are shown. The nodes and

antinodes for the first harmonic are indicated in the diagram by N and A respectively.

7.4

Standing sound waves in pipes: closed pipe

Standing waves can also occur in a pipe that is closed at one end. In this case the air at the

closed end is not free to move so a node (N) occurs there.

Example 9: Length of pipe required to produce a specific frequency.

If the speed of sound in air is 345 m s−1 what length of organ pipe is required for a fundamental

frequency of 45.0 Hz if the pipe is (a) closed (b) open? (c) What would be the wavelength in

each case?

Solution:

13

(a) For a closed pipe:

L=

λ

V

345

=

=

= 1.92 m.

4

4f

4 × 45.0

L=

V

345

λ

=

=

= 3.84 m.

2

2f

2 × 45.0

(b) For an open pipe:

(c) Since the frequency is the same for both pipes, the wavelength is also the same. Thus

λ=

V

345

=

= 7.67 m.

f

45

L

First harmonic

(Fundamental mode

of vibration)

λ1

4

V

f1 =

4L

L=

A

N

Third harmonic (First

overtone) f3 = 3f1

3λ3

4

3V

f3 =

4L

Fifth harmonic (Second

overtone) f5 = 5f1

5λ5

4

5V

f5 =

4L

L=

L=

Figure 10: Various modes of vibration for a sound wave in a closed pipe.

In general, for the nth harmonic,

fn =

nV

4L

n = 1, 3, 5, . . . .

for

(14)

Note that for a closed pipe only odd harmonics can occur.

8

Resonance

Vibrations of stretched strings and of air columns in pipes provide examples of resonance.

14

For example if one end of a stretched string is held fixed whilst the other is vibrated with

small amplitude by a vibrator of adjustable frequency f , standing waves occur whatever the

value of f . However when f becomes equal to one of the natural frequencies

s

n

T

,

fn =

2L µ

resonance occurs (see Equation (12)). At resonance, the amplitude at the antinodes is very

much larger than at the driven end and standing waves are sustained.

Similarly, if a tuning fork is held over a ‘closed’ pipe of adjustable length, resonance occurs

(i.e. a relatively loud sound is heard) when the length is equal to a value corresponding to the

fundamental or one of the overtones (see Figure 11).

λ/4

3λ/4

5λ/4

Fundamental

Second

harmonic

Third

harmonic

Figure 11: Resonance in a closed pipe.

9

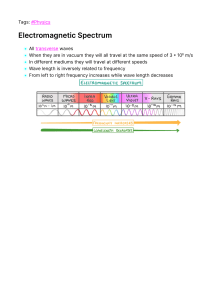

The electromagnetic spectrum

Light waves are transverse waves. They have vibrations at right angles to the direction in

which they travel.

Light waves, radio waves, microwaves, infrared waves, ultra-violet waves, X-rays and γrays (from radioactive sources) all have the same physical nature and basically differ only in

wavelength. They are described as transverse electromagnetic waves and together make up

the complete electromagnetic spectrum.

For all electromagnetic waves v = f λ holds. Furthermore, for an electromagnetic wave

travelling in a vacuum, the speed is equal to the speed of light in vacuum c = 3.0 × 108 m s−1

(This value may be used in air to a good approximation.) Hence for electromagnetic waves,

c =fλ .

(15)

The wavelength of visible light is usually quoted in nanometres. For example, visible light

corresponds to a range of wavelengths from about 400 nm (violet light) to 700 nm (red light).

15

10−12

γ-rays

10−10

X-rays

10−8

10−6

UV

10−4

infrared

10−2

100

microwaves

102

104 λ(m)

radio waves

z }| {

visible light

Figure 12: The electromagnetic spectrum

A typical microwave wavelength on the other hand, would be of the order of a few centimetres. Microwave ovens for example operate on a wavelength of 12.2 cm.

Example 10: The wavelength of an electromagnetic wave.

One of the East Coast Radio frequencies is 95.7 MHz. Determine the corresponding wavelength.

Solution:

We use Equation (15) with c = 3.0 × 108 m s−1 :

λ=

c

3.0 × 108 m s−1

= 3.13 m.

=

f

95.7 × 106 s−1

16

Problems

Waves

Unless otherwise stated, take the speed of sound in air at 0 ◦C as 331 m s−1 . The speed of

electromagnetic radiation c = 3.0 × 108 m s−1 .

B1 A person standing in the ocean notices that after a wave crest passes by, ten more crests

pass in a time of 120 s. What is the frequency of the wave?

(0.083 Hz)

B2 The right-most key on a piano produces a sound wave that has a frequency of 4185.6 Hz.

Assuming the speed of sound in air is 343 m s−1 , find the corresponding wavelength.

(8.19 × 10−2 m)

B3 A person fishing from a pier observes that four wave crests pass by in 7.0 s and estimates

the distance between two successive crests as 4.0 m. The timing starts with the first

crest and ends with the fourth. What is the speed of the wave?

(1.7 m s−1 )

B4 The wavelength of a sound wave in air is 2.76 m at 0 ◦C. What is the wavelength of

this sound in water at 0 ◦C? (Use the data in Table 1 of your notes.) (Hint: since the

frequency is dependent on the source, it is the same in both media.)

(12.3 m)

B5 At a height of ten metres above the surface of a lake, a sound pulse is generated. The

echo from the bottom of the lake returns to the point of origin 0.140 s later. The air and

water temperatures are 0 ◦C. How deep is the lake? (Refer to Table 1 of your notes.)

(59 m)

B6 On a day when the temperature is 0 ◦C, a man is watching as spikes are being driven to

hold a steel rail in place. The sound of each sledgehammer blow reaches him in 0.14 s

through the rail and in 2.0 s through the air, after he sees the blow fall. Find the speed

of sound in the rail.

(4.7 × 103 m s−1 )

B7 If the speed of sound in air at 0 ◦C is 331 m s−1 , what will it be at 27 ◦C?

(347 m s−1 )

B8 Calculate (a) the speed and (b) the wavelength of a sound wave in air at 45 ◦C produced

by a tuning fork of frequency 400 Hz.

(357 m s−1 ; 0.893 m)

B9 At a football game, a stationary spectator is watching the halftime show. A trumpet

player in the band is playing a 784 Hz tone while marching directly towards the spectator

at a speed of 0.900 m s−1 . On a day when the speed of sound is 343 m s−1 , what frequency

does the spectator hear?

(786 Hz)

17

B10 A hawk is flying directly away from a bird watcher at a speed of 11.0 m s−1 . The hawk

produces a shrill cry whose frequency is 865 Hz. The speed of sound is 343 m s−1 . What

is the frequency that the bird watcher hears?

(838 Hz)

B11 On a day when the speed of sound in air is 340.0 m s−1 a siren mounted on a car emits

a note whose frequency is 1000 Hz.

(a) Determine the frequency of the sound heard by a stationary observer when the car

approaches him with a speed of 40.00 m s−1 .

(b) Determine the frequency heard by an observer moving toward the car with a speed

of 40.00 m s−1 while the car remains stationary.

(1133 Hz;

1118 Hz)

B12 A speeding motorcyclist passes a stationary police car. The car siren is started (the car

still being stationary) and the motorcyclist hears a frequency of 900 Hz. If the true siren

frequency is 1000 Hz and the speed of sound in the air is 343 m s−1 , (a) calculate the

speed of the motorcyclist. The police car starts up in pursuit and soon reaches a speed of

43.0 m s−1 , still sounding its siren. (b) What frequency does the motorcyclist now hear?

(34.3 m s−1 ; 1029 Hz)

B13 The security alarm on a parked car goes off and produces a frequency of 1000 Hz. As

you drive towards this parked car, pass it and drive away, you observe the frequency to

change by 99 Hz. Calculate your own speed. (Take the speed of sound in the air as

343 m s−1 .)

(17 m s−1 )

B14 A tuning fork vibrates at a frequency of 521 Hz. An out-of-tune piano string vibrates at

519 Hz. How much time separates successive beats?

(0.5 s)

B15 Two guitars are slightly out of tune. When they play the ‘same’ note simultaneously,

the sounds they produce have wavelengths of 0.776 m and 0.769 m. On a day when the

speed of sound is 343 m s−1 , what beat frequency is heard?

(4 Hz)

B16 A tuning fork of frequency 400 Hz is moved away from an observer and towards a flat wall

with a speed of 2 m s−1 , the air temperature being 27 ◦C. What is the apparent frequency

(a) of the unreflected sound wave coming directly towards the observer and (b) of the

sound waves coming to the observer after reflection? (c) How many beats are heard?

(398 Hz; 402 Hz; 4 Hz)

B17 On a hot night a bat emitting ‘squeaks’ of frequency 100 kHz flies with a speed of 20 m s−1

towards a stationary bat which is emitting squeaks of the same frequency. When the

squeaks of the two bats occur together, a beat note of frequency 6 kHz is produced, as

recorded by a suitable detector near the stationary bat. Calculate the night temperature.

(Take the speed of sound in air at 0 ◦C as 330 m s−1 .)

(40 ◦C)

B18 Standing waves are set up on a string with a frequency of 20 Hz and a distance between

successive nodes of 0.070 m. Determine the speed with which the separate waves travel

along the string.

(2.8 m s−1 )

18

B19 With a source of sound of frequency 5000 Hz, stationary waves are formed in air at 0 ◦C.

The distance between successive antinodes is 3.31 cm. At a higher temperature it is

found that the separation of the antinodes with the same source is 3.43 cm. Calculate

(a) the speed of sound in air at 0 ◦C (b) the temperature at which the second observation

was made.

(331 m s−1 ; 20.2 ◦C)

B20 A source of frequency 256 Hz is emitting sound energy in air at 0 ◦C. The velocity of

sound in air at 0 ◦C is 330 m s−1 .

(a) If an observer sets up a stationary wave system by intercepting the original sound

wave with a reflecting barrier, what would be the distance between successive nodes?

(b) If the air temperature rises to 20 ◦C, what would be the new sound wave velocity?

(c) If the observer moves steadily towards the source, would the apparent frequency be

higher than, the same as, or lower than the true frequency? Explain your answer

carefully but without the use of formulae.

(d) What beat frequency would be heard if a second source is sounded, of frequency

260 Hz (the observer being stationary)?

(0.645 m;

342 m s−1 ;

higher;

4 Hz)

B21 A string of length 2.0 m and mass 40 g is under a tension of 8.0 N. Calculate the speed

with which a transverse wave will travel along it.

(20 m s−1 )

B22 Two strings made of the same material have the same length and are under the same

tension. The second string has twice the diameter of the first. Determine the ratio of

the velocities of transverse waves along them.

(2:1)

B23 A clothesline 4.5 m long has a mass of 0.61 kg. One end is fastened to a house and the

other end runs over a pulley. (a) If a child of mass 36 kg hangs on the free end, what

is the velocity of a transverse disturbance travelling in the clothesline? (b) What will be

the fundamental frequency of oscillations in the clothesline?

(51 m s−1 ; 5.7 Hz)

B24 The lowest note on a piano has a fundamental frequency of 27.5 Hz and is produced by

a wire that has length 1.18 m. The speed of sound in air is 343 m s−1 . Determine the

ratio of the wavelength of the sound wave to the wavelength of the waves that travel on

the wire.

(5.3)

B25 The A string of a violin has a mass per unit length of 0.60 g m−1 and an effective length

of 330 mm. (a) Find the tension required for its fundamental frequency to be 440 Hz.

(b) If the string is under this tension, how far along the fingerboard (from the tuning

pegs end) should it be pressed in order to vibrate at a fundamental frequency of 495 Hz,

which corresponds to note B?

(51 N; 37 mm)

B26 What will be the fundamental frequency and first two overtones for a 26 cm long organ

pipe if it is (a) open and (b) closed? (Take the speed of sound in air as 343 m s−1 .)

Sketch the displacement curve diagram in each case.

B27 A cylindrical tube sustains standing waves at the following frequencies: 500, 700 and

900 Hz. There are no standing waves at frequencies of 600 and 800 Hz. (a) What is the

19

fundamental frequency? (b) Is the tube open at both ends or just one end?

open at one end)

(100 Hz;

B28 A tube of air is open at only one end and has a length of 1.5 m. This tube sustains a

standing wave at its third harmonic. What is the distance between one node and the

adjacent antinode?

(0.50 m)

B29 The fundamental frequencies of two air columns are the same. Column A is open at both

ends while column B is open at only one end. The length of column A is 0.60 m. What

is the length of column B?

(0.30 m)

B30 A tube is open at both ends, has a length of 2.50 m and is at a temperature of 310 K.

The speed of sound at 293 K is 343 m s−1 . Find the fundamental frequency of the tube.

(70.6 Hz)

B31 A light wave travels through air at a speed of 3.0 × 108 m s−1 . Red light has a wavelength

of about 6.6 × 10−7 m. What is the frequency of red light?

(4.5 × 1014 Hz)

B32 One of the Radio Zulu broadcasting frequencies is 90.8 MHz. What is the corresponding

wavelength?

(3.30 m)

20

Index

Amplitude, 2

Antinodes, 9

Doppler effect, 4

Electromagnetic spectrum, 15

Frequency, 1

beats, 7

Interference, 6

constructive, 6

destructive, 6

Linear superposition, 6

Nodes, 8

Oscillations, 1

Period, 2

Resonance, 14

Wave

longitudinal, 1, 3

mechanical, 1

standing, 8

transverse, 1

travelling, 1

Wavelength, 2

21