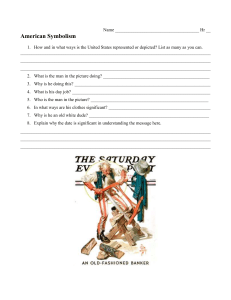

Chapter 8 Symbolism Copyright 2019. John Catt Educational. All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law. Literary symbolism is a hidden code that is threaded throughout literature of all kinds. It is wrapped up in complex layers of mythology, religious texts, linguistic history, art and culture. This means that it can act like an inaccessible barrier to many students, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds. Images aren’t always symbolic; an apple does not always signal temptation or danger, but it often does, and it’s an easy win for analysis and context. It would be impossible to list every literary symbol that has ever been used and – to complicate matters – many symbols have a range of different meanings in different contexts, genres and periods. For example, in some literature the colour yellow is symbolic of decay and old age, whereas in Victorian poetry, it is often associated with youth and angelic purity. Rather than attempt to provide an exhaustive list, I have outlined below some of the more fruitful areas of symbolism, with some examples. Colours Red often symbolises love, passion, danger, blood, violence, death, warning, power, or a range political ideologies. Black is often related to death, evil, or depression. White often signifies innocence, purity, virginity, light, or hope. Depending on the text and context, you might find that colours mean different things in a range of cultures and literary periods. Seasons of the year The season in which a text is set often contributes to the atmosphere and general tone. As seasons change over the course of texts (often in novels), this can also signal a shift in atmosphere and the trajectory of some characters. Spring: birth, new life, new beginnings. Summer: plenty, happiness. Autumn: old age, decline, reaping what is sown. Winter: death, sleep, stillness, stagnation. Plants Roses: beauty, youth, romance, a young woman. The Virgin Mary is often referred to as a ‘rose without thorns’ since she was free of original sin. Lilies are traditional funeral flowers: death, peace, stillness. Poppies: remembrance, death, war, loss. Weeds: evil, outcasts, wildness. Oak trees: masculinity, strength, endurance, faithfulness, Englishness. Willow trees: femininity and women. Fruit trees: knowledge, temptation. Weather Fog/mist: confusion, mystery, isolation. Rain: sadness, despair, depression. Wind and Storms: violent emotions. Lightning/thunder: power, God’s wrath, punishment. EBSCO Publishing : eBook High School Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 2/23/2023 8:57 AM via TSU NATIONAL SCIENCE LIBRARY AN: 3097641 ; Jennifer Webb.; How To Teach English Literature : Overcoming Cultural Poverty Account: ns335569.main.ehost 85 Animals There are a lot of animal symbols and they are often wrapped up in folklore and religious stories. Some of the most prominent are: Birds: flight, freedom/entrapment. Dove: peace, purity. Raven: death, foreboding. Lion: power, authority, royalty. Snake: evil, the Devil, deceit. Symbolic biblical and classical stories There are lots of classic texts and religious stories that have directly influenced many writers (both consciously and sub-consciously). Sometimes we teach texts where writers directly reference existing stories, for example, in The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Utterson says ‘I incline to Cain’s heresy’. This reference suggests that, like Cain, Utterson believes that he is not the keeper of his fellow man. This Biblical story of murder, passion and jealousy is also clearly linked to the key themes in Stevenson’s novel. Our students need to know something of the meaning of this story in order to fully appreciate this moment in the text. In other cases, symbolism from classic stories is far subtler, and it is up to the teacher to make a choice about what to teach, what will be useful, and what to leave. We cannot possibly teach or know everything. Here are some – but not all – of the most common biblical stories which crop up in literary symbolism. Adam and Eve, Genesis Temptation, weakness, paradise, punishment, pain. Cain and Abel, Genesis Original sin, sacrifice, punishment, wrath of God, responsibility, brotherhood. Job, The Book of Job Endurance, faith, trials. Samson and Delilah, The Book of Judges Seduction, power, women, deceit, strength, pride. Noah’s Ark, Genesis Punishment, God’s wrath, rebirth, new beginnings, faith, salvation. The Virgin Mary and the Birth of Christ, New Testament Immaculate conception, purity, sacrifice, motherhood. The Crucifixion and Resurrection of Christ, New Testament Sacrifice, faith, redemption, suffering. The Betrayal of Judas, New Testament Deceit, guilt, betrayal, treason, desire. The Conversion of St Paul, New Testament Revelation, faith, teaching, conversion. For an example of how you might approach classical and biblical allusions in the classroom, see Section 5: Practical Walkthrough. As with everything else we teach, students only need to write about symbolism where it is going to enhance their analysis. They shouldn’t try to shoehorn it in to every point they make. As an addition to an existing strong piece of analysis, discussion of literary symbolism can add a huge amount to written responses: EBSCOhost - printed on 2/23/2023 8:57 AM via TSU NATIONAL SCIENCE LIBRARY. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use 86 Browning creates an incredibly sinister atmosphere in the start of this poem; when Porphyria ‘glide(s)’ in, she comes out of the storm. The storm outside is angry and destructive, ‘it tore down the elm-tops for spite,’ which foreshadows the brutal violence later in the poem. The storm outside is in direct contrast with the ‘warm’ cottage and the ‘blaze’ in the fireplace. Porphyria arrives and the reader is suddenly aware of a shift in tone; it is calm, comfortable and safe inside the cottage. In creating this contrast, Browning sets up an opposition between Porphyria inside and the storm outside. The storm symbolises power and uncontrolled fury, while this beautiful young woman represents peace and vulnerability. Section Summary Reading and Analysis Strategies for Disadvantaged Students Be unashamedly ambitious and aspirational for these students; they have further to go! When teaching language, structure and form, make sure you focus on what’s relevant and useful. Students don’t need to ‘feature spot’, they need to analyse texts in a meaningful way. Teach students to select the best quotations from the text, and to pull them apart to use them in as many ways as possible (look at the range of resources in this chapter). Help students to talk about what the writer might mean – make them feel like they are critics with valid opinions. Teach students to use tentative academic language. Teach students context alongside the text, not as a standalone history lesson. Model clearly how they should talk about context in a specific, meaningful way. If you are going to teach literary theory, do it well and in a way that empowers students to agree and disagree with a range of interpretations. For poetry – especially with GCSE anthologies -– make a clear plan to teach a few at a time rather than inflicting death by poetry and doing them all at once. For drama, find ways of helping students to see that it’s a play. Teach symbolism so that students can unlock texts and feel that they are in on the secret too. EBSCOhost - printed on 2/23/2023 8:57 AM via TSU NATIONAL SCIENCE LIBRARY. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use 87 Section 3 Writing EBSCOhost - printed on 2/23/2023 8:57 AM via TSU NATIONAL SCIENCE LIBRARY. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use 88