A Preface to Marketing Management, 15e Paul Peter, James Donnelly

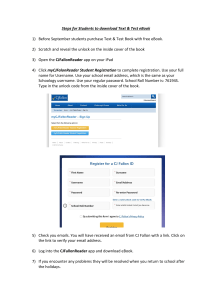

advertisement