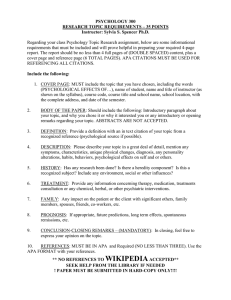

APA PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS Increasing Psychology’s Role in Health Research and Health Care This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Suzanne Bennett Johnson Florida State University The reductionistic, exclusionary, and dualistic tenets of the biomedical model have profoundly affected U.S. health care and health research as well as psychology practice, psychological science, and graduate education in psychology. Although the biomedical model was a success story in many ways, by the end of the 20th century its limitations had become increasingly apparent. These limitations included the biomedical model’s failure to adequately address the changing nature of disease facing the U.S. health care system, escalating health care costs, the role of behavior in health and illness, and patients’ mental health concerns. Medicine’s recent paradigm shift from the biomedical to the biopsychosocial model is occurring in U.S. health care, professional medical education, and health research, with significant implications for psychology. This paradigm shift provides psychology with both opportunities and challenges. Psychology must proactively and deliberately embrace the biopsychosocial model if it is to take full advantage of the opportunities this paradigm shift presents. The American Psychological Association can play an important leadership role in this effort. Keywords: biomedical, biopsychosocial, health research, health care F or over 100 years, the biomedical model has dominated Western medicine. Its impact has been broad and profound, increasing life expectancy and emphasizing biologic approaches to health care and health research. However, with the changing nature of disease, rising health care costs, increasing recognition of the importance of behavior to health, and the model’s failure to adequately address mental health problems, the limitations of the biomedical model have become more and more apparent. This has resulted in a paradigm shift from a biomedical to a biopsychosocial conceptualization of health and disease. This paradigm shift is occurring in health care, professional medical education, and health research, with significant implications for psychology. The Biomedical Model and Its Legacy Stedman’s Medical Dictionary (2006) defines the biomedical model as “a conceptual model of illness that excludes psychological and social factors and includes only biologic factors in an attempt to understand a person’s medical illness or disorder.” Since the wide acceptance of Louis Pasteur’s (1822–1895) germ theory of disease, the biomedJuly–August 2013 ● American Psychologist © 2013 American Psychological Association 0003-066X/13/$12.00 Vol. 68, No. 5, 311–321 DOI: 10.1037/a0033591 ical model has dominated Western medicine (Shore, McDowell, Johnson, & Donovan, 2011). Figure 1 illustrates the clinical course of disease from a biomedical perspective. The body is exposed to some sort of external pathogen, a germ or a poison, for example. This leads to the onset of disease. The preclinical phase— before the emergence of symptoms—may vary in duration from months to days or even minutes depending on the pathogen. Once symptoms occur, the patient may seek medical assistance. Diagnosis involves identifying the most likely biologic mechanism underlying the symptoms and initiating therapy. If the therapy is effective, the patient is “cured.” If the therapy is ineffective, the patient may deteriorate or even die. The model also provides a possible feedback loop in cases of ineffective therapies; in such cases, new diagnostic tests are run in an effort to correctly identify the underlying pathogen and recommend a successful therapy. The biomedical model is characterized by an exclusive focus on disease. It is both reductionistic and exclusionary. Disease is defined as a biologic defect, and whatever is not explained by an underlying biologic defect is excluded from consideration. This approach, in turn, fosters mind– body dualism in which biologic (somatic) processes are considered separate from, and superordinate to, the processes of the mind (emotions, cognitions, behavior; Engel, 1977). The legacies of the biomedical model are biologic assays and diagnostic tools, biologic interventions, and biologic research. Biomedical Model Successes In many respects, the biomedical model has been extremely successful. The germ theory of disease led to sanitation, the development of antibiotics, a remarkable decline in infectious disease, and increasing life expectancy. In 1900, the leading causes of death were tuberculosis, pneumonia and influenza, and diarrheal diseases. Thanks to the biomedical Editor’s note. Suzanne Bennett Johnson was president of the American Psychological Association (APA) in 2012. This article is based on her presidential address, delivered in Orlando, Florida, at APA’s 120th Annual Convention on August 3, 2012. Author’s note. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Suzanne Bennett Johnson, Department of Medical Humanities & Social Sciences, College of Medicine, 1115 West Call Street, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306-4300. E-mail: suzanne .johnson@med.fsu.edu 311 Macleod discovered insulin in dogs; in 1922, insulin was tested in a 14-year-old boy dying of type 1 diabetes. Insulin was truly a miracle drug; the boy recovered, and Banting and Macleod won the Nobel Prize for their work in 1923. Children with type 1 diabetes are still treated with daily insulin injections today, and life expectancy for these children has steadily increased in the postinsulin era (Gale, 2012). This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Impact of the Biomedical Model on U.S. Health Care Suzanne Bennett Johnson model, these diseases are no longer the primary causes of death in the developed world (Centers for Disease Control, n.d.). With the decline in mortality due to infectious disease, over the last 100 years we have seen a remarkable increase in U.S. life expectancy from 49 years in 1901 (Glover, 1921) to 77 years in 2001 (Arias, 2004). The biomedical model’s search for the underlying biologic defect led to very successful biologic interventions to treat a number of diseases. For example, before insulin was discovered, children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes died of their disease. In 1921, Frederick Banting and John Figure 1 The Clinical Course of a Disease From the Biomedical Perspective Note. Reprinted from “Disease as a Process: Natural History and Clinical Course” in AFMC Primer on Population Health (Part 1, chap. 1) by The Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada Public Health Educators’ Network, http://phprimer.afmc.ca/Part1-TheoryThinkingAboutHealth/Chapter1Concepts OfHealthAndIllness/DiseaseorSyndrome (Accessed June 3, 2013). License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA. 312 It is not surprising that the biomedical model’s reductionistic, exclusionary focus on biologic defects underlying disease would have a major impact on the U.S. health care system. The model’s mind– body dualism led to a separation or “carving out” of mental health or behavior problems from the larger health care system, which remained devoted to the diagnosis and treatment of physical disease. In this system, physical complaints are given greater credence, and resources are devoted primarily to biologic assays, biologic interventions, and biologic research. In contrast, mental or behavioral problems are not considered “real” or are undervalued, fewer resources are devoted to treating and researching these problems, and treatments are delivered outside of the larger health care system. In fact, mental health expenditures account for only 6% of all U.S. health care expenditures (Mark et al., 2007). In contrast, the pharmaceutical industry—an industry predicated on biologic interventions— has fared very well in a health care system based on the biomedical model. Nearly two thirds of all Americans take prescription drugs, and over 90% of those 65 years of age and older do. The cost of these drugs keeps escalating, from $65 billion in 1996 to $271 billion in 2010 (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 1996, 2010). Even within the mental health arena, expenditures for prescription drugs for mental health and behavior problems now far exceed expenditures for physicians or all other mental health providers combined (psychologists, counselors, social workers; Mark, Levit, Vandivort-Warren, Buck, & Coffey, 2011). Taking prescription medications to address health—and even mental health— concerns is consistent with the biomedical model’s basic tenet that biologic interventions are most likely to successfully address the biologic defect that underlies the patient’s concerns. Training programs to prepare physicians and mental health providers to work in the U.S. health care system have mirrored the mind– body dualism of the biomedical model. Mental health and physical health providers are trained separately, with greater resources and prestige assigned to one type of professional training over the other. This has resulted in an imbalance in the number of welltrained and well-paid providers, strongly favoring physical health providers. Within this system, psychologists— experts on emotion, cognition, and behavior—are “mental health” providers, and physicians (with the possible exception of psychiatrists) are the “physical health” providers. July–August 2013 ● American Psychologist This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Impact of the Biomedical Model on U.S. Health Research Over the last 40 years, biomedical research has enjoyed a meteoric rise in funding (see Figure 2). While funding for other sciences, including psychology, has remained relatively flat, funding for biomedical research has increased from approximately $3 billion in 1970 to over $25 billion in 2000; no other science comes close to this level of funding (Koizumi, 2008). In this funding zeitgeist, we see the rise of cognitive, affective, behavioral, and social neuroscience. Table 1 provides a listing of some of the major journals in this area with their inception dates and descriptions of their areas of coverage; all are clearly focused on psychological processes, but by using the neuroscience label, the study of psychological phenomena presumably becomes more acceptable within the biomedical framework. This was mimicked within federal funding agencies with the 1997 establishment of the Division of Neuroscience and Basic Behavioral Science within the National Institute of Mental Health, whose priority areas include “how cognitive, affect, stress, and motivational processes interact and their role(s) in mental disorders through functional studies spanning levels of analysis (genomic, molecular, cellular, circuits, behavior) during development and throughout the lifespan” and “fundamental mechanisms (e.g., genetic, biological, behavioral, environmental) of complex social behavior” (National Institute of Mental Health, 2013, “Areas of High Priority,” para. 2, 3). Within the National Science Foundation, the Cognitive Neuroscience Program was established in 2002 to fund “interdisciplinary proposals aimed at advancing a rigorous understanding of how the human brain supports thought, perception, affect, action, so- cial processes, and other aspects of cognition and behavior” (National Science Foundation, n.d., “Synopsis”). Clearly the biomedical model has not been friendly to psychological or social science and has encouraged the metamorphosis of psychological phenomena into a neuroscience framework. Limitations of the Biomedical Model Despite the numerous successes of the biomedical model and its profound impact on U.S. health research and health care, by the end of the 20th century, the model’s limitations were becoming increasingly apparent. The leading causes of death were no longer infectious diseases, and the biomedical model was less successful at addressing the chronic disease challenges facing the United States today. U.S. health care costs continue to rise, unmitigated and perhaps even enhanced by the biomedical model’s emphasis on biologic assays and diagnostic tests and biologic interventions. The role of behavior in disease etiology, prevention, and management has become increasingly obvious. The failure to adequately address mental health concerns by relying on a separate “carved out” underfunded system has further undermined confidence in the biomedical model’s ability to address the modern health care concerns facing the United States. Changing Nature of Disease and Rising Health Care Costs While infectious disease was the leading cause of death in 1900, today most Americans die of chronic disease: heart disease, cancer, chronic lower respiratory diseases, and stroke (Hoyert & Xu, 2012). Nearly one in two U.S. adults has at least one chronic illness. Seven in 10 U.S. deaths are the result of chronic disease, and chronic diseases account Figure 2 Trends in Federal Research by Discipline, FY 1970 –2011 Note. Obligations in billions of constant fiscal year (FY) 2012 dollars. “Other” includes research not classified (includes basic research and applied research; excludes development and R&D facilities). Life sciences are split into National Institutes of Health support and all other agencies’ support. (Source: National Science Foundation, Federal Funds for R&D series. FY 2010 and 2011 are preliminary. Includes Recovery Act funding beginning in FY09. Constant-dollar conversions based on Office of Management and Budget’s gross domestic product deflators.) From “Guide to R&D Funding Data – Historical Data, by Discipline,” by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.aaas.org/spp/rd/guihist.shtml. Copyright 2012 by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Reprinted with permission. July–August 2013 ● American Psychologist 313 Table 1 Journals Addressing Cognitive, Affective, Behavioral, and Social Neuroscience This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Journal Inception date Description Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 1989 Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Neuroscience Social Neuroscience 2001 Social, Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience Cognitive Neuroscience 2009 “investigates brain–behavior interaction and . . . developments in neuroscience, neuropsychology, cognitive psychology, neurobiology, linguistics, computer science, and philosophy” “the leading vehicle for strongly psychologically motivated studies of brain–behavior relationships” “examines how the brain mediates social cognition, interpersonal exchanges, affective/cognitive group interactions, and related topics that deal with social/personality psychology” “addresses issues of mental and physical health as they relate to social and affective processes as long as cognitive neuroscience methods are used” “publishes papers on any topic in the field of cognitive neuroscience including: perception, attention, memory, language, action, decision-making, emotions, and social cognition” 2006 2010 for 75% of the U.S. health care costs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Not only has the biomedical model failed to successfully address these new health care challenges, but the cost of U.S. health care continues to escalate. In 1960, annual per person health care expenditures were $147; in 2011, they were $8,680 (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2012). While the United States leads the world in health care expenditures, U.S. life expectancy remains lower than that in most other developed countries (O’Rourke & Iammarino, 2002). Increasing Recognition of the Role of Behavior in Health Although mortality statistics are commonly reported by disease, in their seminal 1993 article, McGinnis and Foege pointed out that the factors underlying these diseases were often behaviors: smoking, poor dietary habits, sedentary behavior, substance abuse, and so forth. They termed these underlying factors “actual causes of death,” arguing that the leading causes of death in the United States were not heart disease, cancer, and stroke but tobacco, poor diet and inactivity, and alcohol abuse. This analysis was compelling because it pointed out that certain behaviors such as smoking were linked to many diseases (e.g., cancer, heart disease, chronic pulmonary disease) and, as a consequence, were responsible for far more deaths than a single disease entity. Updated for 2000, smoking remains the leading cause of death in the United States, but obesity is now a close second (Mokdad, Marks, Stroup, & Gerberding, 2004). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that health behaviors account for 50% of health outcomes in the United States, a far larger proportion than genetics (20%), the environment (20%), and access to health care (10%; Amara et al., 2003). Beginning in the 1960s, the U.S. Office of the Surgeon General has issued 37 reports on smoking and health, repeatedly bringing attention to the critical role behavior 314 plays in the nation’s health. In addition to reports on smoking, the Office has issued reports on television and youth violence and numerous reports on nutrition, physical activity, and obesity (all reports may be accessed at http:// www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/index.html). In 1979, the Office initiated the Healthy People reports, which identify the nation’s objectives for improving health. These reports are revised every 10 years and highlight the critical role of behavior in Americans’ health and well-being (see (http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx). In 1982, the Institute of Medicine published Health and Behavior: Frontiers of Biobehavioral Research, a landmark volume that emphasized the importance of behavior to health. This was followed by a number of other important reports: Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies From Social and Behavioral Research (2000); From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development (2000); and Health and Behavior: The Interplay of Biological, Behavioral, and Societal Influences (2001). (All of these reports can be retrieved at http:// www.iom.edu/Reports.aspx). Just like the reports from the Office of the Surgeon General, these Institute of Medicine publications gave important scientific credence to the role of behavior in health. Although these reports emphasized the role of behavior in disease prevention and health promotion, behavior is also critical to the management of disease, particularly chronic disease. Patients suffering from chronic disease are often expected to carry out multiple daily disease management tasks at home. These tasks might include medication taking, dietary or exercise modifications, or physiological assessments (e.g., blood pressure monitoring or blood glucose testing). Patients often fail to adhere to these treatment regimens, and poor adherence is often linked to poorer health outcomes and higher health care costs (Johnson, 2012; Willey et al., 2000). The importance of behavior to successful disease management extends beyond patient beJuly–August 2013 ● American Psychologist This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. havior; provider behavior can be just as problematic. In 2000, the Institute of Medicine published a seminal report documenting that medical errors are so widespread and serious that they are the eighth leading cause of death in the United States (Kohn, Corrigan, & Donaldson, 2000). Some have estimated that half of the medical recommendations made to patients are actually inappropriate (Myers & Midence, 1998). Clearly, both patient and provider behavior are critical to chronic disease management. The biomedical model’s failure to include behavior in its conceptual framework underlies its failure to successfully address the chronic disease challenges facing our nation. In response, new structures within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) began to emerge. In 1995, the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research was established. Even the Human Genome Project—an inherently biomedical enterprise—recognized the importance of a broader perspective with the 1990 establishment of the National Human Genome Research Institute’s Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications Research Program. Failure to Adequately Address Mental Health Concerns Mental health concerns are common—26% of U.S. adults have a mental disorder, and 6% have a serious mental disorder—and are the leading cause of disability in the United States (National Institute of Mental Health, 2008). Most patients bring their mental health concerns to their primary care provider. However, given the mind– body dualism of the biomedical model, primary care physicians are ill-equipped to address these concerns. Many patients’ mental health problems go unrecognized or untreated or are inappropriately treated (Kathol, Bulter, McAlpine, & Kane, 2010; Young, Klap, Sherbourne, & Wells, 2001). To complicate matters further, mental health disorders are frequently co-morbid with physical disorders. As many as 40% of medical patients are co-morbid for a mental health disorder and as many as 75% of seriously mentally ill patients are comorbid for a physical disorder (Kessler, Ormel, Demler, & Stang, 2003). Patients who are comorbid for both physical and mental disorders can be extremely costly; total health care expenditures for such patients may be twice those for patients who suffer from a medical or mental illness alone (Druss, Rosenheck, & Sledge, 2000). The biomedical model’s failure to adequately address mental health concerns is one of its major limitations. Many believe that the mind– body dualism of the U.S. health care system is one component of its escalating health care costs. When patients’ mental health concerns go unaddressed or are inappropriately treated, health care costs rise in a neverending effort to identify the biologic defect underlying the patient’s complaints. Medicine’s Paradigm Shift From the Biomedical to the Biopsychosocial Model In 1977, George Engel, an American internist at the University of Rochester, introduced the biopsychosocial model July–August 2013 ● American Psychologist in an article in Science. He argued that the biomedical model—the dominant model of Western medicine—was inadequate because it is reductionistic, exclusionary, dualistic and “leaves no room within this framework for the social, psychological, and behavioral dimensions of illness” (Engel, 1977, p. 135). Although Engel’s biopsychosocial model gained considerable credence within academic circles and among health psychologists, until very recently, it had little or no impact on the U.S. health care system, which remained strongly aligned with the biomedical model. Although Engel did not provide a conceptual diagram of his biopsychosocial model, many were subsequently developed. Figure 3 provides one example (Evans & Stoddart, 1990). Note that the biomedical model is a small component of this larger framework. Some pathogen or poison (a subset of the Physical Environment) or some genetic defect (as subset of the Genetic Environment) impacts the patient’s biology (a subset of the Individual Response), resulting in Disease. Biologic diagnostic tools and biologic therapeutics are then used (a subset of Health Care) in an effort to treat the Disease. The framework of the biopsychosocial model considers a broader array of social, environmental, and genetic factors that might affect the individual. The Individual Response is expanded to include behavior in addition to biology. Health Care might include a variety of assessment strategies, therapeutics, and delivery systems in addition to those that are purely biomedical. In this biopsychosocial framework, disease is no longer the primary outcome of interest. Rather, the model articulates the importance of Health, Function, and WellBeing in addition to Disease per se. While the biomedical model’s exclusionary, reductionistic focus on disease leads to mind– body dualism and an emphasis on biologic assays and biologic treatments, the biopsychosocial model rejects Figure 3 Evans and Stoddart’s (1990) Biopsychosocial Model Note. Reprinted from “Producing Health, Consuming Health Care,” by R. G. Evans & G. L. Stoddart, 1990, Social Science & Medicine, 31, p. 1359. Copyright 1990 by Elsevier Ltd. 315 the separation of mind and body and incorporates environmental, social, and behavioral factors in its effort to understand health, illness, and well-being. In this model, treatments may be behavioral, environmental, or biologic. Medicine’s paradigm shift away from the biomedical model toward the biopsychosocial model is under way; this paradigm shift is likely to have a profound impact on U.S. health care, medical education, and health research. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Implications of the Biopsychosocial Model for U.S. Health Care There is considerable interest in a new approach to health care based on the biopsychosocial model: patient-centered integrated care. When health care is patient-centered and integrated, mind– body dualism is abandoned and the patient is viewed as a whole person. All of the patient’s needs are addressed by an interprofessional health care team that includes both health and mental health expertise in a nonstigmatizing environment that considers the patient’s preferences and culture. To the extent that these tenets of patient-centered care can be realized in actual practice, we would expect increased quality of care (all of the patient’s concerns are addressed, not just physical concerns), greater access to care (patients have immediate access to highquality mental health care as well as medical care), reduced stigma (mental health concerns are not ignored or “carved out” to some third party), lower costs (when all of the patient’s concerns are addressed, unnecessary diagnostic tests in search of some underlying biologic defect may be avoided and appropriate treatments are more likely to be administered), and greater patient satisfaction (the patient feels listened to and cared for and receives any needed treatments in a timely fashion). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (available at http://www.healthcare.gov/law/full/index.html) is consistent with the tenets of patient-centered care and the framework of the biopsychosocial model. Essential health benefits are not limited to medical concerns but must include mental health, preventive and wellness services, and chronic disease management—aspects of health care that have been previously “carved out” or completely ignored. The Affordable Care Act stipulates that the services listed in the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s A (high certainty that the net benefit is substantial) and B (high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial) recommendations must be provided. Currently, of 45 A and B recommendations, 11 are behavioral (see Table 2). A number of other behavioral recommendations are under review (e.g., counseling to prevent tobacco use in children and adolescents, counseling to prevent child abuse and neglect, screening for suicide risk, screening for intimate partner violence and elder abuse; see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/topicsprog .htm). Consequently, we can expect additional behavioral screening and counseling recommendations to become part of the essential health benefits as the scientific evidence warrants their inclusion. 316 In addition to focusing on patient behavior and wellbeing, the Affordable Care Act repeatedly highlights the importance of provider behavior. In addition to requiring evidence-based screening and interventions as part of the essential benefits like those described in Table 2, the Act emphasizes patient safety and the reduction of medical errors. The electronic medical record, including decision support systems, is often viewed as a mechanism to enhance patient safety and reduce medical errors. Unlike the disease focus of the biomedical model, the Affordable Care Act also highlights patient functioning and quality of life as important health outcomes, establishing the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, which focuses on “outcomes that people notice and care about such as survival, function, symptoms, and health related quality of life” (see http://www.pcori.org/research-wesupport/pcor/). Implications of the Biopsychosocial Model for Health Provider Education Recent policies of the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC; 2011) highlight the expanding influence of the biopsychosocial model on medical education. Based on the AAMC’s 2011 report, Behavioral and Social Science Foundations for Future Physicians, the structure of the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) will change in 2015 and will include a section on psychological, social, and biological foundations of behavior, accounting for one quarter of the exam questions (see https://www.aamc.org/ download/273766/data/finalmr5recommendations.pdf). Currently, medical school accreditation requires instruction in behavioral science as well as adequate training in patient–provider communication skills, the impact of patient culture and beliefs, the medical impact of common societal problems, and the impact of provider bias and beliefs (Liaison Committee for Medical Education, 2012). The larger health care community’s acceptance of patient-centered integrated care delivered by health care teams is highlighted in the Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice (Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, 2011), a collaborative effort of the AAMC, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine, the American Dental Education Association, and the Association of Schools of Public Health. Implications of the Biopsychosocial Model for Health Research As the Affordable Care Act illustrates, the biopsychosocial model changes the concern of evidence-based medicine from a narrow focus on disease to a wide array of potential patient outcomes—patient satisfaction, functioning, and quality of life, to name a few. Instead of a narrow focus on biologic assays and biologic interventions, a wider variety of treatment options—including psychological or behavioral treatments— can be tested as part of the scientific July–August 2013 ● American Psychologist Table 2 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) A and B Behavioral and Counseling Recommendations Relevant to the Implementation of the Affordable Care Act Topic Alcohol misuse counseling This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. BRCA screening and counseling Breastfeeding counseling Depression screening: adolescents Depression screening: adults Healthy diet counseling Obesity screening and counseling: adults Obesity screening and counseling: children Sexually transmitted infections counseling Tobacco use counseling and interventions: nonpregnant adults Tobacco use counseling: pregnant women USPSTF recommends: Grade Effective date Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce alcohol misuse by adults, including pregnant women, in primary care settings Women whose family history is associated with an increased risk for deleterious mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes be referred for genetic counseling and evaluation for BRCA testing Interventions during pregnancy and after birth to promote and support breastfeeding Screening for adolescents (12–18 years of age) for major depressive disorder when systems are in place to ensure accurate diagnosis, psychotherapy (cognitivebehavioral or interpersonal) and follow-up Screening for adults for depression disorder when staffassisted depression care supports are in place to ensure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up Intensive behavioral dietary counseling for adult patients with hyperlipidemia and other known risk factors of cardiovascular disease and diet-related chronic disease Clinicians screen all adult patients for obesity and offer intensive counseling and behavioral interventions to promote sustained weight loss for obese adults Clinicians screen children aged 6 years and older for obesity and offer them or refer them to comprehensive, intensive behavioral interventions to promote improvement in weight status High-intensity behavioral counseling to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) for all sexually active adolescents and for adults with increased risk for STIs Clinicians ask all adults about tobacco use and provide tobacco cessation interventions for those who use tobacco products Clinicians ask all pregnant women about tobacco use and provide augmented, pregnancy-tailored counseling to those who smoke B 2004 B 2005 B 2008 B 2009 B 2009 B 2003 B 2003 B 2010 B 2008 A 2009 A 2009 Note. Adapted from “USPSTF A and B Recommendations” by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce .org/uspstf/uspsabrecs.htm. enterprise. New areas of inquiry, such as translation research and implementation science, are attracting some of the best scientific minds. But perhaps most important, the biopsychosocial model encourages interdisciplinary research or team science in which scientists with differing areas of expertise come together to address the complexities of understanding and promoting health as well preventing and treating disease. Epigenetics, pharmacogenomics, and personalized medicine are just a few of these new interdisciplinary areas of inquiry. Interdisciplinary science was the focus of the National Academy of Sciences’ 2004 groundbreaking report Facilitating Interdisciplinary ReJuly–August 2013 ● American Psychologist search (National Research Council, 2004). It is also a component of the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research’s “Research Teams of the Future,” consisting of investigators from many disciplines combining their skills and knowledge to accelerate discovery. The NIH has set aside funds “to change academic research culture such that interdisciplinary approaches and team science spanning various biomedical and behavioral specialties are encouraged and rewarded” (http://commonfund.nih.gov/interdisciplinary/). Using data obtained from the NIH’s Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT; see http://projectreporter .nih.gov/reporter.cfm), I found that funded grants that used 317 the search terms “multidisciplinary” or “interdisciplinary” in their titles or abstracts increased sevenfold from 1990 to 2010; total funding for these projects increased fourfold from 2000 to 2010.1 This analysis likely underestimates the extent of interdisciplinary funding at NIH, since many interdisciplinary science teams do not choose to use these search terms in their titles and abstracts. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Implications of the Biopsychosocial Model for Psychology The biopsychosocial model is consistent with psychology’s multivariate conceptual heritage and its scientific and methodological expertise. Many psychologists have been early adopters of the model and proponents of its development and application. These include health psychologists, pediatric psychologists, rehabilitation psychologists, neuropsychologists, geropsychologists, and primary care psychologists, to name a few. These psychologists already work in public health as well as primary and specialty health care settings. Psychologists have been leading scientists in the development of interdisciplinary fields such as neuroscience, behavioral genetics, psychoneuroimmunology, medical decisionmaking, and bioethics. Three of the first four directors of the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research at the NIH have been psychologists: Norman Anderson, David Abrams, and Robert Kaplan. However, the impact of the biomedical model on psychology practice, psychological science, and graduate education in psychology has been profound. The reductionistic, exclusionary, dualistic tenets of the biomedical model meant that psychological practice or science was excluded or “carved out” from the larger health care and health research enterprise. In response, most psychologists became solo practitioners and solo scientists focusing their efforts primarily on mental health, working in their own offices or laboratories with little collaboration with other medical practitioners or scientists from other disciplines. Graduate psychology programs responded by preparing students to succeed in this environment. As a consequence, many psychologists feel ill prepared to adapt to the interprofessional practice or interdisciplinary science framework that the biopsychosocial model demands. Many professional psychologists have no experience working on health care teams in larger group practices or health care settings. They have been trained solely in mental health and have no expertise in addressing a wide array of behavioral issues common in health care (e.g., medical regimen adherence, pain management, coping with disability, life style behavior change). They are unfamiliar with the larger health care culture, including evidence-based practice, treatment guidelines, and electronic health records. They have no experience with how to collaborate with other health care providers and organizations to develop new payment models to assure mental health coverage as part of patient-centered integrated care. 318 Although health research is now conducted primarily by interdisciplinary science teams, many of our psychological scientists have never been trained to operate in such environments. Other scientists on these teams are often unfamiliar with the contributions psychological science can make or are openly hostile to such contributions. With no experience on such teams, psychological scientists often fail to defend their role successfully, if they attempt to join a science team to begin with. Our academic hiring and tenure practices further discourage interdisciplinary science and encourage solo science by valuing first-author and single-author publications and funding above all else and discouraging cross-discipline hiring.2 Medicine’s paradigm shift from the biomedical to the biopsychosocial model presents remarkable opportunities for psychology in both health care and health research. However, if psychology is to take advantage of these opportunities, it must abandon the mind– body dualism of the biomedical model and fully embrace the biopsychosocial model in practice, research, and graduate education. This means that practicing psychologists must be trained to function as health providers, not just mental health providers, delivering services as members of interprofessional health care teams. Similarly, psychological scientists must be trained to function successfully on interdisciplinary science teams and to embrace the wide array of interdisciplinary sciences— epigenetics, psychoneuroimmunology, personalized medicine, clinical trials, dissemination research, to name a few— that will characterize the health science of the future. In my view, psychology must be proactive and deliberate in its acceptance of medicine’s paradigm shift to the biopsychosocial model. No one will plead with psychology or wait for psychology to act. If psychology does not embrace this paradigm shift, others will fill the gap, providing the needed mental health services on interprofessional heath care teams and the behavioral science on the interdisciplinary science teams of the future. While others may step in if psychology does not, I do not believe psychology’s remarkable professional and scientific heritage can be easily matched. As a consequence, psychology’s failure to act will be a loss not only for psychology but also for quality patient care and health research. The American Psychological Association’s Response As the largest association of U.S. psychologists and the largest publisher of psychological science in the world, it is critical that the American Psychological Association (APA) provide leadership in this time of unprecedented opportunity and challenge for psychology. A number of APA policies are very consistent with evidence-based medicine, the Affordable Care Act, and medicine’s ongoing 1 No funding data were available before 2000. This issue is not limited to psychology but is a problem across academia. 2 July–August 2013 ● American Psychologist This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. paradigm shift to the biopsychosocial model, providing an important framework for APA’s leadership in this area (all of the following APA policies are available in the Council Policy Manual at http://www.apa.org/about/policy/index .aspx): Recognition of Psychologists as Health Service Providers (1996); Changing U.S. Health Care System (1999); Criteria for Evaluating Treatment Guidelines (2000); Health Service Psychologists as Primary Care Providers (2003); Evidence-Based Practice in Psychology (2005); Health Care for the Whole Person: Vision and Principles (2005); and APA Principles for Health Care Reform (2007). Two components of APA’s strategic plan— expanding psychology’s role in health and increasing the recognition of psychology as a science—are consistent with APA leadership in assuring psychologists as active participants in the interprofessional practice and interdisciplinary science teams of the future (see http://www.apa.org/about/ apa/strategic-plan/default.aspx for more on APA’s strategic plan). For the first time, APA is undertaking the major task of developing evidence-based treatment guidelines. The first guideline will focus on depression, and the second guideline will focus on obesity. These two topics highlight the broad role psychologists can play in the larger health care arena. In the 1970s, medicine was faced with overwhelming data showing that very little medical practice was based on scientific research. In response, evidencebased medicine and the development of scientifically grounded treatment guidelines became widely accepted (Eddy, 2005). It is important that APA join the evidencebased movement if it is to be a true player in health care. Psychologists have important expertise to offer and can play a critical role in assuring that psychological interventions are part of evidence-based treatment guidelines. Consistent with the biopsychosocial model, patients should have access to effective psychological interventions and not be limited to drugs or other biologic treatments. (To learn more about APA’s treatment guideline efforts, go to http://www.apa.org/about/offices/directorates/guidelines/ clinical-treatment.aspx). APA has also been very active in graduate education relevant to training psychologists to practice in integrated care. APA lobbied successfully for the Graduate Psychology Education Program that established psychology as a health profession within the federal Bureau of Health Professions grant programs in 2001. This program currently provides competitive funding to accredited doctoral, internship, and postdoctoral programs for psychology students providing services to underserved populations in interdisciplinary integrated health care settings. (To learn more, go to http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/grants/mentalbehavioral/gpe.html). APA is also a member of the Health Service Psychology Education Collaborative, an interorganizational group that has articulated the necessary competencies for psychologists to practice as health service providers (Health Service Psychology Education Collaborative, in press). In a similar partnership, APA joined with nine other July–August 2013 ● American Psychologist organizations to produce a document identifying the competencies for psychological practice in primary care (McDaniel et al., 2013). These reports provide important resources for practicing psychologists wanting to expand their skills to function in the larger health care arena and for the Commission on Accreditation and the graduate programs that are responsible for training the next generation of professional psychologists to function effectively in health care. Finally, although not a party to the development of the Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice (Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, 2011), APA’s Council of Representatives took the important step of endorsing this document in 2013. Most recently, APA joined with the American Psychological Association Practice Organization to establish a new Center for Psychology and Health. The goal of the center, directed by APA CEO Norman Anderson, is to expand the use of psychological knowledge within evolving health care settings as well as prepare psychologists to practice in these settings. A unit of the center, the Office of Health Care Financing, will focus on payment models that are fair and sustainable for both health systems and practitioners. The office will coordinate APA’s participation in the American Medical Association’s (AMA’s) Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) Editorial Panel—where CPT codes describing psychologists’ work are developed—and the AMA’s Relative Value Scale Update Committee, where those procedure codes are valued. (To learn more about the Center go to http://www.apa.org/health/index .aspx). It is critically important that other health practitioners understand the value of having psychological expertise on their health care teams. However, these teams cannot be sustained unless new payment models are developed. The Center will play critical roles both internally— educating psychologists—and externally— educating and collaborating with other health care providers and their organizations to assure patient access to high-quality psychological expertise. APA is also committed to conducting a work force analysis as one of its strategic initiatives. A work force analysis is sorely needed in order to respond to the nation’s work force needs of the future and to assure an adequate response by the discipline. However, psychology’s work force analysis will look very different if professional psychology is viewed as a central player in patient-centered integrated health care than if it remains a “carved out” mental health profession. Finally, APA is committed to a path toward interdisciplinary science broadly conceived, including interdisciplinary health research. Interdisciplinary education, professionalism, and science were the foci of the 2011 Education Leadership Conference (for more information, go to http:// www.apa.org/ed/governance/elc/2011/index.aspx). APA has also produced a task force report relevant to this issue (APA 2009 Presidential Task Force on the Future of Psychology as a Stem Discipline, 2010) and is currently represented on the Council of Scientific Society Presidents’ Committee on Interdisciplinary Science. The purpose of 319 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. this committee is to do more than identify barriers to interdisciplinary science—such as hiring practices, promotion and tenure requirements, and funding formulas— but to identify solutions. There are a host of creative models that have successfully been used to increase both interdisciplinary science and teaching within the academy. By articulating models and solutions, APA can join with other scientific organizations to promote interdisciplinary science that includes psychology. APA’s leadership is important if psychology is to take advantage of medicine’s paradigm shift from the biomedical to the biopsychosocial model. However, APA cannot do this alone. Individual psychologists and other psychological associations, at the state and national levels, must be proactive and deliberate, joining with APA, each other, and other health care providers and their organizations to make patient-centered integrated care a reality. REFERENCES Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (1996). Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 1996. Retrieved from http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/ data_stats/quick_tables_results.jsp?component⫽1&subcomponent⫽ 0&year⫽1996&tableSeries⫽-1&searchText⫽&searchMethod⫽1& Action⫽Search Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2010). Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2010. Retrieved from http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/ data_stats/quick_tables_results.jsp?component⫽1&subcomponent⫽0& year⫽2010&tableSeries⫽-1&searchText⫽&searchMethod⫽1&Action⫽ Search Amara, R., Bodenhorn, K., Cain, M., Carlson, R., Chambers, J., Cypress, D., . . . Yu, K. (2003). Health and health care 2010: The forecast, the challenge. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. American Association for the Advancement of Science. (2012). Guide to R&D funding data – historical data, by discipline. Retrieved from http://www.aaas.org/spp/rd/guihist.shtml American Association of Medical Colleges. (2011). Behavioral and social science foundations for future physicians. Retrieved from https:// www.aamc.org/download/271020/data/behavioralandsocialscience foundationsforfuturephysicians.pdf American Psychological Association 2009 Presidential Task Force on the Future of Psychology as a Stem Discipline. (2010). Psychology as a core science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) disclipline. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/science/about/psa/2010/ 08/stem-report.pdf Arias, E. (2004). United States life tables, 2001. National Vital Statistics Reports, 52(14). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/ nvsr52/nvsr52_14.pdf Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). The power of prevention: Chronic disease . . . the public health challenge of the 21st century. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/pdf/2009power-of-prevention.pdf Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Leading causes of death, 1900 –1998. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/ lead1900_98 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2012). National health expenditures; aggregate and per capita amounts, annual percent change and percent distribution, and average annual percent growth, by source of funds: Selected calendar years 1960 –2011. Retrieved from http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/StatisticsTrends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/tables.pdf Druss, B. G., Rosenheck, R. A., & Sledge, W. H. (2000). Health and disability costs of depressive illness in a major U.S. corporation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1274 –1278. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157 .8.1274 Eddy, D. M. (2005). Evidence-based medicine: A unified approach. Health Affairs, 24, 9 –17. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.9 320 Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196, 129 –136. doi:10.1126/science.847460 Evans, R. G., & Stoddart, G. L. (1990). Producing health, consuming health care. Social Science & Medicine, 31, 1347–1363. doi:10.1016/ 0277-9536(90)90074-3 Gale, E. A. M. (2012). Historical aspects of type 1 diabetes. Retrieved from http://www.diapedia.org/type-1-diabetes-mellitus/2104085134/ historical-aspects-of-type-1-diabetes Glover, J. (1921). United States life tables, 1890, 1901, 1910, and 1901– 1910. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/lifetables/life18901910.pdf Health Service Psychology Education Collaborative. (in press). A blueprint for health service psychology education and training. American Psychologist. Hoyert, D. L., & Xu, J. (2012). Deaths: Preliminary data for 2011. National Vital Statistics Reports, 61(6). Retrieved from http://www .cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_06.pdf Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. (2011). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/ ipecreport.pdf Johnson, S. B. (2012). Adherence to medical regimens. In D. YoungHyman & M. Peyrot (Eds.), Psychosocial care for patients with diabetes (pp. 117–130). Alexandria, VA: American Diabetes Association. Kathol, R. G., Butler, M., McAlpine, D. D., & Kane, R. L. (2010). Barriers to physical and mental condition integrated service delivery. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72, 511–518. doi:10.1097/PSY .0b013e3181e2c4a0 Kessler, R. C., Ormel, J., Demler, O., & Stang, P. E. (2003). Comorbid mental disorders account for the role impairment of commonly occurring chronic physical disorders: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 45, 1257–1266. doi:10.1097/01.jom.0000100000.70011.bb Kohn, L., Corrigan, J., & Donaldson, M. (Eds.). (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Retrieved from http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php? isbn⫽0309068371 Koizumi, K. (2008). Federal funding for research and development and the federal budget. Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved from http://www.aaas.org/spp/rd/ presentations/prapprop208.pdf Liaison Committee for Medical Education. (2012). Functions and structure of a medical school: Standards for accreditation of medical education programs leading to the M.D. degree. Retrieved from http:// www.lcme.org/functions.pdf Mark, T., Levit, K., Coffey, R., McKusick, D., Harwood, H., King, E., . . . Ryan, K. (2007). National expenditures for mental health services and substance abuse treatment 1993–2003. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from http://store.samhsa.gov/product/National-Expenditures-for-Mental-HealthServices-and-Substance-Abuse-Treatment-1993-2003/SMA07-4227 Mark, T. L., Levit, K. R., Vandivort-Warren, R., Buck, J. A., & Coffey, R. M. (2011). Changes in US spending on mental health and substance abuse treatment, 1986 –2005, and implications for policy. Health Affairs, 30, 284 –292. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0765 McDaniel, S., Grus, C., Cubic, B., Hunter, C., Kearney, L., Schuman, C., . . . Johnson, S. B. (2013). Competencies for psychology practice in primary care. Manuscript submitted for publication. McGinnis, J. M., & Foege, W. (1993). Actual causes of death in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association, 270, 2207–2212. doi:10.1001/jama.1993.03510180077038 Mokdad, A. H., Marks, J. S., Stroup, D. F., & Gerberding, J. L. (2004). Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, 291, 1238 –1245. doi:10.1001/jama.291 .10.1238 Myers, L., & Midence, K. (Eds.). (1998). Adherence to treatment in medical conditions. Newark, NJ: Gordon & Breach. National Institute of Mental Health. (2008). The numbers count: Mental disorders in America. Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/ publications/the-numbers-count-mental-disorders-in-america/index.shtml# MoreInfo July–August 2013 ● American Psychologist Stedman’s medical dictionary (28th ed.). (2006). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Retrieved from http://www.stedmansonline .com U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2013, January). USPSTF A and B recommendations. Rockville, MD: Author. Retrieved from http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsabrecs .htm Willey, C., Redding, C., Stafford, J., Garfield, F., Geletko, S., Flanigan, T., . . . Caro, J. J. (2000). Stages of change for adherence with medication regimens for chronic disease: Development and validation of a measure. Clinical Therapeutics, 22, 858 – 871. doi:10.1016/S01492918(00)80058-2 Young, A. S., Klap, R., Sherbourne, C. D., & Wells, K. B. (2001). The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 55– 61. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. National Institute of Mental Health. (2013). Division of Neuroscience and Basic Behavioral Science (DNBBS). Retrieved from http://www.nimh .nih.gov/about/organization/dnbbs/index.shtml National Research Council. (2004). Facilitating interdisciplinary research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Retrieved from http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id⫽11153#toc National Science Foundation. (n.d.). Cognitive Neuroscience. Retrieved from http://www.nsf.gov/funding/pgm_summ.jsp?pims_id⫽5316 O’Rourke, T. W., & Iammarino, N. K. (2002). Future of healthcare reform in the USA: Lessons learned from abroad. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 2, 279 –291. doi:10.1586/14737167.2.3.279 Shore, B., McDowell, I., Johnson, I. L., & Donovan, D. (2011). A primeron population health: A new resource for students and clinicians. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 41(4, Sippl. 3), S302–S303. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.023 July–August 2013 ● American Psychologist 321