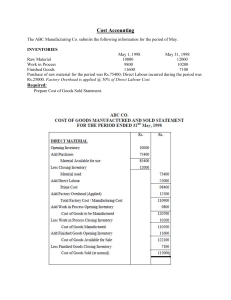

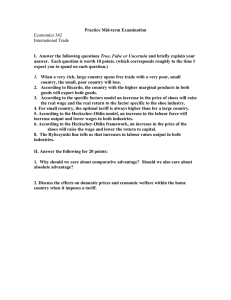

International Economics PRACTICAL INFORMATION ◼ Course: builds on courses of micro- and macro-economics ◼ Prerequisites: micro and macro economics ◼ Guidance/questions: Discussion board on TOLEDO, no e-mail Regular Q&A sessions ◼ Structure: Kaltura recordings combined with interactive Q&A sessions ◼ Handbook: International Trade: Theory and Policy (2018), Paul Krugman, Maurice Obstfeld, Marc Mélitz ◼ Combination of asynchronous (recordings) and synchronous, on-campus teaching (Q&A sessions) ◼ Class recordings and slides: Toledo (Course documents and Collaborate) ◼ Exam: Written Closed book Questions testing both knowledge and understanding Question bundle with 30 multiple choice questions – this also serves as scrap paper. Pre-printed answer sheet: make sure to be in the correct examination room!! Fill in the answer sheet at the end of the exam, using a pen (no pencil). No calculator No correction for guessing ◼ Exam feedback session Advantages and purpose Registration only possible on the day of the announcement of the exam results ◼ If guest lectures: information and study material on Toledo ◼ Contents of the course: cfr. end of this chapter 1 Structure of the course Part 1: International trade theory Chapter 1: Introduction Chapter 2: World Trade Chapter 3: Labour Productivity and Comparative Advantages: the Ricardian Model Chapter 4: Specific Factors and Income Distribution Chapter 5: Production Factors and Trade: the Heckscher-Ohlin model Chapter 7: External Scale Effects and International Location of Production Chapter 8: Firms in the Global Economy: Export Decisions, Outsourcing and Multinational Firms Part 2: International trade policy Chapter 9: Instruments of Trade Policy Chapter 10: Political Economy of Trade Policy Chapter 11: Trade Policy in Developing Countries Chapter 12: Controversies in Trade Policy Planning of the course 2 Chapter 1: What is international economics? What is international economics? ◼ Real economics (= this course) Increase in trade flows Benefits of trade Trade pattern Impact of government policy on trade ◼ Monetary economics (macro- and monetary courses) ◼ International economics studies the economic interactions between countries and the problems that can prevail The study of international economics has never been as important as today: at the beginning of the 21st century, nations are more closely linked through trade in goods and services, through flows of money, and through investment in each others’ economies than ever before – although the benefits of globalization are ever more questioned. Increase in trade flows 3 4 Average of imports and exports as % of GDP is the trade openness of an economy We notice that trade flows increased a lot Why? ▪ Decrease in trade barriers such as tariffs and quota but also decrease of transport costs in general ▪ Free trade areas/agreements (EU, NAFTA/USMCA, …) 5 Benefits of trade Free trade offers benefits and costs The most important benefits are: 1. Even if a country is the most/least efficient in producing all goods it still gains by trading: it focuses on producing the good in which it is relatively best and imports the rest (Ch3) 2. Trade will be beneficial for a country when it exports (imports) goods that intensively use the abundant (scarse) factors of production (Ch4 and 5) 3. If countries specialise they can produce more efficiently because of a larger scale of production (Ch7 and 8) We will illustrate that trade is beneficial for individual countries but can be detrimental for certain groups of economic agents within countries (division of benefits can differ – Ch4/5/11) ▪ Trade can have a negative impact on factors of production that are used in import competing sectors ▪ Trade can thus lead to different income effects within countries ▪ Trade can also lead to different income effects between countries (developed versus developing) Trade pattern Trade pattern can be explained by: ▪ Differences in climate (inter-industrial trade) ▪ Differences in labour productivity (inter-industrial trade) – Ch3 ▪ Differences in availability and use of factors of production (inter-industrial trade) – Ch4 and 5 ▪ Scale effects (intra-industrial trade) – Ch7 and 8 6 Impact of government policy on trade The government can influence trade in a number of ways What are the costs and benefits of such a policy? (Ch9-Ch12) ▪ If a government restricts trade, which instrument(s) does she use best? ▪ If a government restricts trade, to which degree does she do it best? ▪ If a government restricts trade, what are the costs of the policy ánd of the possible counter measures undertaken by trade partners? Example to illustrate the benefits of trade agreements/free trade. Trump: produce cars in US or pay 35% tariff on imported cars from Mexico 7 Chapter 2: World Trade Gravity model explains trade: ▪ Countries trade more when they are larger ▪ Countries trade more when they are closer to one another Changing pattern of world trade ▪ Has the world become smaller? ▪ Which goods are traded? ▪ Outsourcing/offshoring Gravity model explains trade What explains/influences trade? 1. Size of countries ▪ Larger economies produce more goods and services, so they have more to sell in the export market. ▪ Larger economies generate more income from the goods and services sold, so people are able to buy more imports. 2. Distance between countries (influences transport costs + personal contacts) 3. Cultural affinity 4. Geography (harbors, mountains) 5. Multinational corporations 6. Borders (time and money cost; diff in language and currency) 8 In its basic form, the gravity model assumes that only size (+) and distance (-) are important for trade in the following way: Tij = AxYi xY j Dij where Tij is the value of trade between country i and country j A is a constant Yi the GDP of country i Yj is the GDP of country j Dij is the distance between country i and country j ◼ In a slightly more general form, the gravity model that is commonly estimated is Tij = AxY a i xY b j D c ij ◼ Perhaps surprisingly, the gravity model works fairly well in predicting actual trade flows ◼ Estimates of the effect of distance from the gravity model predict that a 1% increase in the distance between countries is associated with a decrease in the volume of trade of 0.7% to 1% ◼ The gravity model can assess the effect of trade agreements on trade: ➔ does a trade agreement lead to significantly more trade among its partners than one would otherwise predict given their GDPs and distances from one another? 9 ◼ E.g. because of NAFTA/USMCA and because Mexico and Canada are close to the US, the amount of trade between the US and its northern and southern neighbors as a fraction of GDP is larger than between the US and European countries. ◼ Even with a free trade agreement between the US and Canada, which use a common language, the border between these countries still seems to be associated with a reduction in trade. ◼ The negative effect of distance on trade according to the gravity models is significant, but it has grown smaller over time due to modern transportation and communication. 10 Changing pattern of world trade: Has the world become smaller? There were different waves of globalization. ▪ 1840–1914: economies relied on steam power, railroads, telegraph, telephones. Globalization was interrupted and reversed by wars and depression. ▪ 1945–present: economies rely on telephones, airplanes, computers, internet, fiber optics,… ▪ From 1945 onwards: recovery of world trade ▪ From 1970 onwards: world trade as a fraction of GDP has increased substantially ▪ Today: recovery of the crisis + increased questioning regarding the benefits of globalization 11 Changing pattern of world trade: Which goods are traded? Today ▪ Most of the volume of trade is in manufactured products (55%) such as cars, computers, clothing, machinery ▪ Importance of trade in services increases (25% of trade is in services) ▪ Mineral products and agricultural products constitute respectively 13% and 7% of trade Before ▪ A large fraction of the volume of trade came from agricultural and mineral products. 12 Changing pattern of world trade: Outsourcing/offshoring ▪ Before 1945 there were hardly any multinationals; now they are everywhere ▪ ‘Outsourcing’ and ‘offshoring’ = what? When a firm that produces goods/services, moves its activities (or part of its activities) abroad ▪ The activities are undertaken by an independent company in another country. or ▪ The activities are undertaken by subsidiaries in another country. Chapter 3: Labor productivity and comparative advantage: the Ricardian model ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ Introduction Concept of comparative advantage Comparative advantage with 2 goods ▪ Relative production and relative prices without trade ▪ Relative production and relative prices with trade ▪ Benefits of trade ▪ Relative wages ▪ Misconceptions about comparative advantage Comparative advantage with more goods ▪ Relative production with trade ▪ Benefits of trade Transport costs and nontraded goods Empirical evidence of the Ricardian model 13 Introduction ◼ Countries engage in international trade for two basic reasons: They are different from each other in terms of climate, land, capital, labor, and technology – Ch3, 4 and 5 They try to achieve scale economies in production – Ch7 and 8 ◼ The Ricardian model is based on technological differences across countries. These technological differences are reflected in differences in the productivity of labor. Concept of comparative advantage ◼ Opportunity Cost The opportunity cost of roses in terms of computers is the number of computers that could be produced with the same resources as a given number of roses. ◼ Comparative Advantage A country has a comparative advantage in producing a good if the opportunity cost of producing that good in terms of other goods is lower in that country than it is in other countries. Numerical example: ◼ Suppose that in the U.S. 10 million roses can be produced with the same resources as 100,000 computers. ◼ Suppose also that in S-America 10 million roses can be produced with the same resources as 30,000 computers. ◼ This example assumes that S-American workers are less productive than U.S. workers. ◼ If each country specializes in the production of the good with lower opportunity costs, trade can be beneficial for both countries. ◼ Roses have lower opportunity costs in S-America. ◼ Computers have lower opportunity costs in the US, ◼ The benefits from trade can be seen by considering the changes in production of roses and computers in both countries. The world as a whole produces more (the same amount of roses but more computers) – it is therefore possible to increase everyone’s life standard 14 The example illustrates the principle of comparative advantage: ◼ If each country exports the goods in which it has comparative advantage (lower opportunity cost), then all countries can in principle gain from trade. What determines comparative advantage? How do country differences determine the pattern of trade? Second intuitive example to illustrate the difference between absolute and comparative advantage: ◼ 2 people: CEO and management assistant ◼ 2 tasks: lead company and writing up reports ◼ Given the following information: CEO is better than the management assistant in leading the company and faster in writing up reports CEO is mainly better in leading the company (5 times more efficient than the management assistant), rather than faster in writing up reports (2 times more efficient than the management assistant) ◼ Questions: Is it profit maximizing for the CEO to fire the management assistant? Who has an absolute/comparative advantage in performing which task? Comparative advantage with 2 goods Relative production and relative prices without trade Assume that we are dealing with an economy (which we call Home). In this economy: Labor is the only factor of production. Only two goods (say wine and cheese) are produced. The supply of labor is fixed in each country. The productivity of labor in each good is fixed. Perfect competition prevails in all markets. ◼ The unit labor requirement is the number of hours of labor required to produce one unit of output. aLW : amount (hours) of labor needed to produce 1 gallon of wine. aLC : amount (hours) of labor needed to produce 1 pound of cheese ◼ The total labor supply in a country is defined by L 15 ◼ 1/aLC is the marginal production ◼ Production Possibilities The production possibility frontier (PPF) of an economy shows the maximum amount of wine that can be produced for any given amount of cheese, and vice versa (the trade-off between two goods). The PPF of our economy is given by the following equation: aLCQC + aLWQW = L or aLWQW = L - aLCQC or QW = L /aLW – aLC /aLW x QC ◼ In an economy with one production factor, the PPF is a straight line ◼ If the PPF is a straight line, the opportunity cost of a pound of cheese in terms of wine is constant: aLC /aLW The production of one pound of cheese requires aLC man-hours Every man-hour could also be used for the production of 1/ aLW gallons of wine ◼ The opportunity cost is the slope of the PPF curve ◼ Example calculation opportunity cost Opportunity cost is aLC / aLW ▪ aLC is number of hours one works in cheese industry = 1 hour ▪ 1/ aLW is wine production per hour = ½ gallon per hour ▪ The opportunity cost of cheese in terms of wine = how much wine one could produce if one does not opt for the production of cheese: take 1 hour from the cheese production and use it for wine production => 1/2 gallons of wine 16 ◼ PPF reveals what a country CAN produce ◼ What a country WILL produce depends on the relative price ◼ Relative Prices and Supply The particular amounts of each good produced are determined by prices The relative price of cheese in terms of wine is the amount of wine that can be exchanged for one unit of cheese ◼ The supply is determined by the maximization decision of employees. They maximize their income by working in the sector that offers the highest wage. PW (PC): price of wine (cheese) wW (wC): wage in the wine (cheese) industry ◼ Hourly wage = value of what a worker can produce in 1 hour wW = PW / aLW wC = PC / aLC Therefore, wC / wW = (PC / PW) / (aLC / aLW) ◼ The relation between relative prices and opportunity cost determines the specialization. If PC / PW > aLC / aLW → wC > wW → specialization in C If PC / PW < aLC / aLW → wC < wW → specialization in W If PC / PW = aLC / aLW → wC = wW → production of both goods ◼ The above relations imply that if the relative price of cheese (PC / PW ) exceeds its opportunity cost (aLC / aLW), then the economy will specialize in the production of cheese. ◼ In the absence of trade, both goods are produced, and therefore PC / PW = aLC /aLW. 17 Comparative advantage with 2 goods: Relative production and relative prices with trade ◼ Assumptions of the model: There are two countries in the world (Home and Foreign). Each of the two countries produces wine and cheese. Labor is the only factor of production. The supply of labor is fixed in each country. The productivity of labor in each good is fixed. Labor is not mobile across the two countries. Perfect competition prevails in all markets. * refers to the Foreign country. ◼ Absolute advantage versus comparative advantage A country has an absolute advantage in the production of a good if it has a lower unit labor requirement than the foreign country in this good: aLC < a*LC and aLW < a*LW 2 labor inputs are required to determine absolute advantage (labour input in cheese at Home and abroad or labour input in wine at Home and abroad) A country has a comparative advantage in the production of a good (cheese) when: aLC /aLW < a*LC /a*LW 4 labor inputs are required to determine comparative advantage (labour input in cheese and wine at Home and labour input in cheese and wine in Foreign) ◼ The pattern of trade will be determined by the concept of comparative advantage ◼ Comparative Advantage Assume that aLC /aLW < a*LC /a*LW o This assumption implies that the opportunity cost of cheese in terms of wine is lower in Home than it is in Foreign. o In other words, in the absence of trade, the relative price of cheese at Home is lower than the relative price of cheese in Foreign. ◼ Home has a comparative advantage in cheese and will export it to Foreign in exchange for wine. ◼ To determine the benefits of trade, we need to know the relative price if there would be trade 18 Note: PPF for F is steeper than for H; The opp cost for cheese in terms of wine is therefore larger in F ◼ In studying comparative advantages, we do not use a ‘partial equilibrium analysis’ (studying 1 particular market, e.g. the market of cheese), ◼ But we use a so-called ‘general equilibrium analysis’, where the linkages between the two different markets – in this case cheese and wine – are studied --> hence the relative demand/supply cheese wrt wine ◼ If no trade : PC / PW = aLC / aLW ◼ What determines the relative price (PC / PW) after trade? To answer this question we have to define the relative supply and relative demand for cheese in the world as a whole. The relative supply of cheese equals the total quantity of cheese supplied by both countries at each given relative price divided by the total quantity of wine supplied, (QC + Q*C )/(QW + Q*W). The relative demand of cheese in the world is a similar concept. 19 20 21 22 ◼ PC / PW < aLC / aLW : H and F produce wine, no cheese production ◼ PC / PW = aLC / aLW : H produces wine and cheese ◼ aLC / aLW < PC / PW < a*LC / a*LW : H produces cheese, F produces wine (full specialization) ◼ PC / PW = a*LC / a*LW : F produces wine and cheese ◼ PC / PW > a*LC / a*LW : H and F produce cheese, no wine production ◼ In point 1 each country specializes fully ◼ In point 2, country 1 still specializes in the production of cheese but also produces wine (relative production of cheese is smaller than with full specialization) ◼ Note that the relative price after trade is most of the time in between the opportunity costs in both countries Comparative advantage with 2 goods: Benefits of trade ◼ The Gains from Trade If countries specialize according to their comparative advantage, they all gain from this specialization and trade. 23 ◼ We will demonstrate these gains from trade in two ways. A first way to see the gains from trade is to consider how trade affects the consumption in each of the two countries. The consumption possibility frontier (CPF) states the maximum amount of consumption of a good a country can obtain for any given amount of the other commodity. In the absence of trade, the consumption possibility curve is the same as the production possibility curve. Trade enlarges the consumption possibility for each of the two countries. Secondly, we can think of trade as a new way of producing goods and services (indirect production). Doel: • Aantonen dat beide landen winnen bij handel • Absoluut voordeel is niet van belang, wel comparatief voordeel 24 ◼ The previous numerical example implies that: aLC / aLW = 1/2 < a*LC / a*LW = 2 In world equilibrium, the relative price of cheese must lie between these values. Assume that PC / PW = 1 gallon of wine per pound of cheese. ◼ Both countries will specialize and gain from this specialization (H:C – F:W) ◼ Home: Home can use one hour of labor to produce 1/aLW = 1/2 gallon of wine if it does not trade. Alternatively, it can use one hour of labor to produce 1/aLC = 1 pound of cheese, sell this amount to Foreign, and obtain 1 gallon of wine. 1 gallon > ½ gallon ◼ Foreign: Foreign can use one hour of labor to produce 1/a*LC = 1/6 pound of cheese if it does not trade. Alternatively, it can use one hour of labor to produce 1/a*LW = 1/3 gallon of wine, sell this amount to Home, and obtain 1/3 pound of cheese. 1/3 pound > 1/6 pound Comparative advantage with 2 goods: Relative wages ◼ Relative Wages Because there are technological differences between the two countries, trade in goods does not make the wages equal across the two countries. A country with absolute advantage in both goods will enjoy a higher wage after trade. ◼ This can be illustrated with the help of a numerical example: Assume that PC = $12 and that PW = $12. Therefore, we have PC / PW = 1 as in our previous example. Since Home specializes in cheese after trade, its wage will be (1/aLC)PC = ( 1/1)$12 = $12. Since Foreign specializes in wine after trade, its wage will be (1/a*LW) PW = (1/3)$12 = $4. Therefore the relative wage of Home will be $12/$4 = 3. Thus, the country with the higher absolute advantage will enjoy a higher wage after trade. 25 ◼ The relative wage is between the productivity ratios of both goods: H is 6 time more productive in cheese production and 1,5 times more productive in wine production than F The wage in H is 3 time higher than the wage in F ◼ These relationships imply cost advantages for both countries: In H, higher wages are compensated for by a higher productivity In F, lower productivity is compensated for by a lower wage ◼ In the Ricardian model, relative wage differences reflect relative productivity differences Is this true in reality? Yes Comparative advantage with 2 goods: Misconceptions about comparative advantage ◼ Productivity and Competitiveness Myth 1: Free trade is beneficial only if a country is strong enough to withstand foreign competition. This argument fails to recognize that trade is based on comparative not absolute advantage. ◼ The Pauper Labor Argument Myth 2: Foreign competition is unfair and hurts other countries when it is based on low wages. Lower wages in Foreign simply reflect a lower productivity – Home still benefits from trade. ◼ Exploitation Myth 3: Trade makes the workers worse off in countries with lower wages. In the absence of trade these workers would be worse off. Denying the opportunity to export is to condemn poor people to continue to be poor. 26 Comparative advantage with MORE goods: Relative production with trade ◼ The Model: Both countries consume and are able to produce a large number, N, of different goods. ◼ Relative Wages and Specialization The pattern of trade will depend on the ratio of Home to Foreign wages (w/w*) Goods will always be produced where it is cheapest to make them. ◼ H will produce and export good i if: waLi < w*a*Li (or if a*Li /aLi > w/w*) ◼ How determine ratio of domestic and foreign wages (w/w*)? o Easy in 2-goods model: ▪ If H has a comparative advantage in cheese: determine w in terms of cheese and w* in terms of wine ▪ Then use relative price to calculate relative wage → this was only possible because we already knew the specialization o Less easy in more goods model: → we don’t know the specialisation yet – we need the relative wage to determine the specialisation How proceed? Look at relative demand and relative supply of labour – relative demand for labour is deducted from relative demand for goods ◼ Which country produces which goods? A country has a cost advantage in any good for which its relative productivity is higher than its relative wage. ◼ If, for example, w/w* = 3, Home will produce apples, bananas, and caviar, while Foreign will produce only dates and enchiladas. ◼ Both countries will gain from this specialization (direct versus indirect production). 27 ◼ Determining the Relative Wage in the Multigood Model To determine relative wages in a multigood economy we must look behind the relative demand for goods (i.e., the relative derived demand) The relative demand for Home labor depends negatively on the ratio of Home to Foreign wages Comparative advantage with more goods: Benefits of trade ◼ Illustrate benefits of trade: direct versus indirect production; e.g. H imports dates If import (indirect): 1 date ‘costs’ 12 units of labour in F If own production (direct): 1 date ‘costs’ 6 units of labour in H ◼ NOTE: these two units of labour cannot be compared why not? Because they are expressed in different units: wages in H are three times higher than wages in F If import: 1 date ‘costs’ 12 units of labour in F = 4 units of labour in H If own production: 1 date ‘costs’ 6 units of labour in H 4 units of labour in H < 6 units of labour in H so importing dates is beneficial for H Transport costs and nontraded goods ◼ There are three main reasons why specialization in the real world is not extreme: The existence of more than one factor of production. Countries sometimes protect industries from foreign competition. It is costly to transport goods and services. 28 ◼ The result of introducing transport costs makes some goods nontraded. ◼ In some cases transportation is virtually impossible. ◼ Example of non-tradable goods because of transport costs Caviar: exported from H to F NO TRANPORT COSTS ◼ H: caviar ‘costs’ 3 units of labour in H = 9 units of labour in F ◼ F: caviar ‘costs’ 12 units of labour in F => Beneficial for F to import TRANSPORT COSTS of 100 % ◼ H: caviar ‘costs’ 9*2 = 18 units of labour in F ◼ F: caviar ‘costs’ 12 units of labour in F => No longer beneficial for F to import Empirical evidence of the Ricardian model ◼ The Ricardian model has several shortcomings: There is never full specialization in the real world One does not take income differences within countries into account There is no role for differences in available production factors The role of economies of scale is ignored ◼ We still see that the basic prediction of the model gets confirmed by several studies ◼ Balassa (1963): compare production and export in the UK and US after the second world war: US has an absolute advantage in everything We however see that UK exports too (even twice as much as US); UK must therefore also have comparative advantages. 29 Chapter 4: Specific factors and income distribution ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ Introduction Specific factors model ▪ Assumptions ▪ Production possibilities ▪ Prices, wages and labour allocation International trade in the specific factors model Income distribution and benefits of trade Trade policy: preview Introduction ▪ If trade is beneficial for an economy, why do we observe so much inhibitions to trade (e.g. subisdies, quotas...)? ▪ In the model of Ricardo (chapter 3): ▪ ▪ Trade leads to international specialisation, where in each country workers are moved from the relative inefficient industry to the relative efficient industry ▪ Labour is assumed to be the only factor of production and it is mobile between industries In reality trade can lead to huge income distributions within a country Two possible reasons: ▪ ▪ Production factors cannot be transferred immediately and/or at zero costs between industries. ▪ Industries differ with respect to the factors of production they need. In chapter 4 we analyse how trade can influence income distribution within a country, assuming a more realistic world than Ricardo: → i.e. a world with more than 1 factor of production, where production factors cannot be transferred immediately and/or at zero costs between industries Specific factors model: Assumptions • Assumptions of the model: ▪ Two goods: clothing (C) and food (F) ▪ Three factors of production: labour (L), capital (K) and land (T) ▪ Perfect competition in all markets ▪ Clothing is produced with capital and labour 30 ▪ Food is produced with land and labour ▪ Labour is a mobile factor of production ▪ Land and capital are both specific factors of production that can only be used for the production of 1 of both goods Specific factors model: Production possibilities ▪ How much of each good will the economy produce? ▪ The production function for Clothing (Food) shows the quantity of Clothing (Food) that can be produced for each given input of capital (land) and labour. QC = QC (K, LC) ▪ (4-1) en QF = QF (T, LF) (4-2) The shape of the production function reflects the law of decreasing marginal revenues. - Moreover, each additional unit of labour adds less output than the previous one (‘diminishing returns’). 31 ▪ For the economy as a whole, the total amount of labour employed in the food and clothing industry together has to equal the total supply of labour: LC + LF = L (4-3) ▪ We use a 4-quadrants diagram to construct the production possibility frontier (Figure 4.3). ▪ Why is the production possibility frontier bent? ▪ ▪ Decreasing revenues for labour in each sector imply an increasing opportunity cost when an economy increases its production. ▪ The opportunity cost of clothing in terms of food is the absolute value of the slope of the production possibility frontier. The opportunity cost to produce one extra unit of clothing: MPLF / MPLC kilograms of food (MPL= marginal product of labour) Specific factors model: Prices, wages and labour allocation ▪ Demand for labour: In each sector, producers will maximise their profits by demanding labour until the point where the value produced by an additional hour of labour equals the marginal costs of employing a worker during that hour. 32 ▪ The demand curve for labour in the clothing sector: MPLC x PC ▪ ▪ (4-4) The demand curve for labour in the food sector: MPLF x PF ▪ = w = w (4-5) Figure 4.4 illustrates the labour demand in two sectors. ▪ The two sectors need to pay the same wage because labour is free to move between the sectors ▪ Where the two demand curves for labour intersect, we find the equilibrium wage and the equilibrium divison of labour between the two sectors There is a relation between output and relative prices: In the production point: MPLC x PC = MPLF x PF = w -MPLF / MPLC ▪ = -PC / PF (4-6) “In the production point, the production possibility frontier (PPF) has to touch a line with a slope equal to: minus the price of clothing divided by the price of food.” 33 ▪ What happens if there is an equal, proportional change in prices (e.g, P C and PF increase by 10 %)? ➢ PC and PF increase by 10 % ➢ w also increases by 10 % ➢ The allocation of labour between the two sectors remains exactly the same ➢ The real income of capital owners and landowners remains exactly the same 34 ▪ What happens if there is a change in relative price (e.g. PC increases by 7 %) ➢ When only PC increases, the relative price PC / PF changes ➢ The labour demand curve for the clothing industry shifts ➢ w does not increase as much as PC (since the employment in the clothing industry increases, the marginal product of labour in the sector decreases) ➢ Labour is transferred from the food to the clothing sector 35 • • What is the economic effect of this price increase on the incomes of the following three groups: employers, capital owners and landowners o Employers ? o Capital owners ? o Land owners ? The impact of a relative price change on the income distribution can be summarised as follows: o The production factor specific to the sector in which the relative price increases, is better off o The production factor specific to the sector in which the relative price decreases is worse off o The change in welfare for the mobile factor is ambiguous 36 International trade in the specific factors model ▪ Trade and relative prices ▪ The relative price of clothing without trade is determined by the intersection of the relative supply and the relative demand of clothing in the country considered ▪ The relative price of clothing under free trade is determined by the intersection of the relative world supply and relative world demand for clothing ▪ The relative supply for clothing for the world as a whole (RS world) will differ from the one in the specific factors model in country 1 that we looked at before 37 • If there is free trade in the specific factors model, an economy will export that good whose relative price has increased and import the good whose the relative price has decreased. Income distribution and benefits of trade ▪ Who wins and who loses from trade? ▪ How does trade influence the welfare of different groups? ▪ Summarising: “Trade is beneficial for the factor of production specific to the export sector and harmful for the production factor specific for import competing sectors. Trade has an ambiguous effect on mobile factors of production.” ▪ There are winners and losers from trade … but are the gains larger than the losses? In other words, is trade globally speaking better than protection? ▪ ▪ Can those who win from trade compensate the losers and still be better off themselves? If yes, trade is possibly beneficial to all Value of consumption has to equal value of production (note that D represents consumption and Q production): PCDC + PFDF = PCQC + PFQF ▪ (4-7) This is a budget line with a slope of – (PC /PF): (QF – DF) = – (PC /PF)(QC – DC) 38 (4-8) Trade policy: preview ▪ Often losers are the ‘weaker ones’, i.e. the employers in the import competing sectors that already have a relatively low wage ▪ Is this a reason to limit free trade? No, because of 3 reasons: 1) Income effects are not specific to technological progress, there are for instance also income effects if there is technological progress. Should technological progress as a consequence be limited? 2) It is better to reap the global benefits of trade and compensate the losers 3) The losers of free trade are often better organised than the winners = political argument (cfr. sugar industry US) Chapter 5: Heckscher-Ohlin model ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ Introduction Model of a two-factor economy ▪ Production possibilities ▪ Relationship factor prices and input choices ▪ Relationship factor prices and goods prices ▪ Relationship goods prices and input choices ▪ Relationship input choices and output International trade between two-factor economies Benefits of trade Factor-price equalization Empirical evidence 39 Introduction ◼ In the real world, while trade is partly explained by differences in labor productivity (Ch3), it also reflects differences in countries’ resources (Ch4 and 5). ◼ The Heckscher-Ohlin theory: Emphasizes resource differences as the only source of trade Shows that comparative advantage is influenced by: ◼ Relative factor abundance (refers to countries) ◼ Relative factor intensity (refers to goods) Is also referred to as the factor-proportions theory ◼ Difference specific factors (Ch4) and Heckscher-Ohlin (Ch5) Ch4: ‘short’ term, i.e. certain factors of production are specific and therefore immobile between the sectors Ch5: ‘long’ term, where all factors of production are mobile between the sectors -> Basic idea is the same: differences in available factors of production determine the trade pattern Model of a two-factor economy: Production possibilities • Assumptions of the Model ▪ Two countries: H and F ▪ Two goods, cloth (C) and food (F) ▪ Two production factors: capital (K) and labour (L) ▪ The supply of labour and capital is constant within a country but differs between countries ▪ In the long run, both labour and capital can be transferred from one sector to the other one ▪ Both cloth and food are produced by both capital and labour ▪ Two production functions: ▪ QC = QC (KC,LC ) ▪ QF = QF (KF,LF ) ▪ Perfect competition prevails in all markets ▪ Production of food is capital-intensive and production of cloth is labor-intensive in both countries. LC /KC > LF /KF or aLC /aKC > aLF/aKF or aLC /aLF > aKC /aKF 40 ▪ If more than one factor of production: PPF is no longer a straight line ▪ PPF is influenced by both capital- and labour-requirements (no subsititution inputs possible): aKFQF + aKCQC ≤ K aLFQF + aLCQC ≤ L ▪ Recall that: LC /KC > LF /KF ; this assumption influences the slope of the PPF • The opportunity cost of producing cloth in terms of food is not constant in this model: • o it’s low when the economy produces a low amount of cloth and a high amount of food o it’s high when the economy produces a high amount of cloth and a low amount of food If we allow substitution of inputs, then the PPF becomes curved. 41 • • The production possibility frontier describes what an economy can produce, but to determine what the economy does produce, we must determine the prices of goods. In general, the economy should produce at the point that maximizes the value of production, V: V = PCQC + PFQF where PC is the price of cloth and PF is the price of food • • Define an isovalue line as a line representing a constant value of production. o V = PCQC + PFQF o PFQF = V – PCQC o QF = V/PF – (PC /PF)QC o The slope of an isovalue line is – (PC /PF) At that point, the slope of the PPF equals – (PC /PF), so the opportunity cost of cloth equals the relative price of cloth. 42 Model of a two-factor economy: Relationship factor prices and input choices ▪ Producers can use different quantities of factors of production to produce clothing and food • Their choice of input combinations depends on the wage rate, w, and the rental rate r, more in particular the ratio of these two factor prices: w/r • As the wage rate increases relative to the rental rate, producers are willing to use more capital and less labor in the production of food and cloth (relationship factor prices and factors of production). • Recall that cloth production is labour-intensive, if at any given wage-rental ratio the labourcapital ratio used in the production of cloth is greater than that used in the production of food: LC/KC > LF/ KF • The production of cloth is relatively labour intensive, while the production of food is relative capital intensive 43 Model of a two-factor economy: Relationship factor prices and goods prices • Stolper-Samuelson Theorem (effect): If the relative price of a good increases, holding factor supplies constant, then the nominal and real return (in terms of both goods) to the factor used intensively in the production of that good increases, while the nominal and real return (in terms of both goods) to the other factor decreases. Model of a two-factor economy: Relationship goods prices and input choices • An increase in PC/PF will: o Raise the income of workers relative to that of capital owners, w/r o Raise the ratio of capital to labor, K/L, in both cloth and food production and thus raise (lower) the marginal productivity of labor (capital) in terms of both goods 44 o Raise the purchasing power of workers and lower the purchasing power of capital owners, by raising real wages and lowering real rents in terms of both goods w = MPL*p and r = MPK*p for both goods so w/p = MPL and r/p = MPK Model of a two-factor economy: Relationship input choices and output ▪ To what degree do the production levels change when the factors of production of an economy change? ▪ Rybczynski theorem: “If a factor of production (K or L) increases, then the supply of the good that uses this factor intensively increases and the supply of the other good decreases for any given commodity prices” ▪ We assumed that: ▪ Clothing is labour intensive ▪ Food is capital intensive • Assume the supply of labour increases; i.o.w. the ratio (L/K) increases • An increase in the supply of capital (labor) leads to a biased expansion of production possibilities towards food (cloth) production. • o The biased effect of increases (decreases) in resources on production possibilities is the key to understanding how differences in resources give rise to international trade. o Why? An economy will tend to be relatively effective at producing goods that are intensive in the factors with which the country is relatively well-endowed. 45 International trade between two-factor economies • What if trade happens? o o The two countries have similarities: ▪ Same tastes (so same relative demand) ▪ Same technology ▪ Same production structure The two countries differ: ▪ Different resources: Home is labour abundant and Foreign is capital abundant ▪ Since cloth is labour intensive, for every given relative price of cloth to food, Home will produce a higher ratio of cloth to food than Foreign • If H and F trade, their relative prices converge: relative price of cloth increases in H (from 1 to 2) and decreases in F (from 3 to 2) and we end up in a point between the two pre-trade prices (point 2) • Implications of trade pattern? • o In Home, the rise in the relative price of cloth leads to a rise in the production of cloth and a decline in relative consumption, so Home becomes an exporter of cloth and an importer of food. o Conversely, the decline in the relative price of cloth in Foreign leads it to become an importer of cloth and an exporter of food Heckscher-Ohlin theorem: o A country will export that commodity which uses intensively its abundant factor and import that commodity which uses intensively its scarce factor. 46 Benefits of trade • Trade and the Distribution of Income o Long run ▪ Trade produces a convergence of relative prices. ▪ Changes in relative prices have strong effects on the relative earnings of labor and capital in both countries: ▪ o In Home, where the relative price of cloth rises, workers are made better off and capital owners are made worse off. • In Foreign, where the relative price of cloth falls, the opposite happens, workers are made worse off and capital owners are made better off. Owners of a country’s abundant factors gain from trade, but owners of a country’s scarce factors lose. Short run ▪ • • Production factors that are ‘stuck’ in a particular industry – temporarily or for a longer time period – are called ‘specific factors’ (cfr. Chapter 4) Can those who benefit from trade compensate the losers and still be better off? Yes, cfr. Figure 4.11 Chapter 4 Factor-price equalization • • • In the absence of trade: workers would earn less in Home than in Foreign, and capital owners would earn more. The HO model predicts that factors prices will be equalized if countries trade → Free trade equalizes relative goods prices → As a consequence of the link between goods and factor prices factor prices will also be equalized. How far will this go? According to the model we will get a full equalization of factor prices (wages and rents) Factor-Price Equalization Theorem: o International trade leads to a complete equalization of factor prices. If both goods are produced in both countries, the factor prices will the the same in both countries. This implies that international trade is a substitute for the international mobility of factors of production. • BUT … In the real world factor prices are not equalized between countries o Has international trade equalized the returns to homogeneous factors in different countries in the real world? ▪ Even casual observation clearly indicates that it has not. 47 ▪ Under these circumstances, it is more realistic to say that international trade has reduced, rather than completely eliminated, the international difference in the returns to homogeneous factors. • Four assumptions crucial to the prediction of factor price equalization are in reality untrue: o Both countries produce both goods o Both countries have the same technologies in production o Both countries have the same prices of goods due to trade (often not so because of limitations to free trade) o The remuneration of production factors is the same irrespectively of their industry of employment • The model predicts the outcome in the long run, but when an economy decides to participate in free trade it is possible that production factors cannot immediately be transferred to industries that intensively use abundant factors of production Empirical evidence ▪ Tests on US data o ▪ Leontief paradox: Leontief found that US exports were less capital-intensive than US imports, even though the US is the most capital-abundant country in the world Tests on global data o A study by Bowen, Leamer, and Sveikauskas tested the Heckscher-Ohlin model using data for a large number of countries and confirms the Leontief paradox on a broader level. 𝑒𝑛𝑑𝑜𝑤𝑚𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑐𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑖𝑛 𝑐𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑦 𝑖𝑛𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑒 𝑖𝑛 𝑐𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑦 > 𝑒𝑛𝑑𝑜𝑤𝑚𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑐𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑖𝑛 𝑤𝑜𝑟𝑙𝑑 𝑖𝑛𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑒 𝑖𝑛 𝑤𝑜𝑟𝑙𝑑 ⇒ country exports capital intensive goods 48 ▪ The case of missing trade ▪ A study by Trefler in 1995 showed that technological differences across a sample of countries are very large ▪ Since factor prices are never fully equalised between countries, the predicted trade is mostly a lot larger than the effective trade → This phenomenon is known as the phenomenon of ‘missing trade’ ▪ North-South trade ▪ North-South trade in manufactures seems to fit the Heckscher-Ohlin theory much better than the overall pattern of international trade 49 ▪ Changes through time according to the HO model: ▪ ▪ When Japan and the four Asian ‘miracle’-countries (South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore) became more ‘skill-abundant’ between 1960 and 1998, the US imports from these countries has shifted from ‘less skill intensive industries’ to ‘more skill intensive industries’ – cfr. Fig 5.13 Implications of the tests of the HO model ▪ The HO model has been less successful at explaining the actual pattern of international trade. ▪ It has been useful as a way to analyze the effects of trade on income distribution. 50 Chapter 7: External scale effects and the international location of production ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ Introduction Economic scale effects and international trade Scale effects and market structure Theory of external scale effects External scale effects and international trade Dynamic increasing scale effects International trade and economic geography Introduction ▪ Countries engage in international trade for two basic reasons: Countries trade because they differ either in their resources or in technology (comparative advantages). (Chapters 3-5) Countries trade in order to achieve scale economies or increasing returns in production. (Chapters 7-8) ▪ Implications for trade?: Chapters 3-5: markets are perfectly competitive. All monopoly gains are competed away. With scale effects, large firms have an advantage over small firms, such that markets are often dominated by 1 firm (monopoly) or a limited number of firms (oligopoly). ▪ There are external scale effects (level of the industry) and internal scale effects (level of the individual firm). External scale effects = chapter 7 Internal scale effects = chapter 8 Economic scale effects and international trade ◼ Models of trade based on comparative advantage used the assumptions of constant returns to scale and perfect competition: Increasing the amount of all inputs used in the production of any commodity will increase output of that commodity in the same proportion. Ricardo and HO model assume all incomes of production are transferred to the factors of production; there are no ‘monopoly’gains 51 ◼ In practice, many industries are characterized by economies of scale (also referred to as increasing returns). Production is most efficient, the larger the scale at which it takes place. Output grows proportionately more than the increase in all inputs. Average costs (costs per unit) decline with the size of the market. Scale effects and market structure ◼ External scale effects (chapter 7) The cost per unit depends on the size of the industry but not necessarily on the size of any one firm An industry will typically consist of many small firms and be perfectly competitive ◼ Internal scale effects (chapter 8 ) The cost per unit depends on the size of an individual firm but not necessarily on that of the industry The market structure will be imperfectly competitive with large firms having a cost advantage over small ◼ Both types of scale economies are important causes of international trade 52 Theory of external scale effects There are three main reasons why a cluster of firms may be more efficient than an individual firm in isolation: 1. Specialized suppliers 2. Labor market pooling 3. Knowledge spillovers 1. Specialized Suppliers In many industries, the production of goods and services and the development of new products requires the use of specialized equipment or support services. An individual company does not provide a large enough market for these services to keep the suppliers in business. ◼ A localized industrial cluster can solve this problem by bringing together many firms that provide a large enough market to support specialized suppliers. ◼ Eg. Silicon Valley has a large concentration of silicon chip firms that need particular machines to make these chips 2. Labor Market Pooling A cluster of firms can create a pooled market for workers with highly specialized skills. It is an advantage for: ◼ Producers They are less likely to suffer from labor shortages. ◼ Workers They are less likely to become unemployed. 3. Knowledge Spillovers Knowledge is one of the important input factors in highly innovative industries. The specialized knowledge that is crucial to success in innovative industries comes from: ◼ Research and development efforts ◼ Informal exchange of information and ideas 53 External scale effects and international trade ▪ A country that has large production in some industry will tend to have low costs of producing that good. ▪ Trade with external scale effets happens often, both within and between countries: ▪ ▪ What are the implications of this type of trade? ▪ ▪ ▪ Eg. New York (Manhattan) exports financial services to the rest of the US and the world. External scale effects can make countries stuck in an unwanted pattern of specialisation and can even result in losses from international trade. With external economis of scale, the pattern of trade is often determined by historical coincidence. ▪ Countries that start out as large producers in certain industries (eg. because of historical reasons) tend to remain large producers even if some other country could potentially produce the goods more cheaply. ▪ Eg. Location of financial centers in London and New York is determined by historical events (cfr. book). ▪ A consequence of the role of ‘history’ in determining the location of an industry is the fact that industries are not always localised in the best location. Graphically: external scale effects imply lower costs and therefore lower prices with an increasing output ➔ ‘forward-falling’ supply curve ▪ Example: button industry in China and the US ▪ No trade: equilibrium price and output for each country is where demand and supply curve intersect Suppose: price in China is initially lower ▪ ▪ Trade: equilibrium price and output for the two countries together (‘world’) is where total demand and supply curve of the cheapest producer intersect Intitially lower price in 1 country can be because of: ▪ Better technology ▪ Lower labour costs ▪ Historical events ▪ … 54 ▪ What happens to production and prices if there is trade? ▪ Production? China expand production, production US shrinks ➔ costs in China decrease and costs in US increase until finally all production takes place in China ▪ Prices? Trade leads to lower prices for both China and the US!! DIFFERENCE comparative advantages: ➢ Comparative advantages: trade converges prices, ie increase in 1 country, decrease in the other country ➢ External scale effects: trade decreases prices in both countries 55 ▪ Impact on welfare if external scale effects? ▪ Trade based on external economies has more ambiguous effects on national welfare than either trade based on comparative advantage or trade based on economies of scale at the level of the firm. With external scale effects, a country can be worse off because of ▪ trade Suppose: Vietnam and China are 2 button producers and Vietnam is cheaper ▪ This does not imply that Vietnam will produce for the whole world – if China has a beginners advantage – for whatever reason - China will serve the world market (because Vietnam does not produce enough to benefit from a lower production cost) → It can be better for a country to produce the goods itself rather than to import; iow trade can be negative for an individual country → Trade is and remains beneficial because one can use external scale effects → Total welfare impact = ambiguous ▪ Example of negative welfare impact for 1 country ▪ Watch-industry: Thailand versus Switzerland 56 Dynamic increasing scale effects Until now: costs depend on current output Now: costs depend on accumulated output = Dynamic increasing returns ▪ Costs decrease with cumulative production over time rather than with current production = Learning curve ▪ It relates unit cost to cumulative output ▪ It is downward sloping because of the effect of the experience gained though production on costs Dynamic scale effects justify protectionism ▪ Temporary (!!) protection of industries enables them to gain experience (infant industry argument). ▪ Is this a good argument for trade protection? International trade and economic geography • External scale effects explain trade patterns and therefore also the location of industries = economic geography • Trade and location cannot simply be explained by comparative advantages but also by accident and historical events ▪ Silicon Valley – Hewlett and Packard ▪ LA – movies 57 Chapter 8: Internal scale effects ▪ ▪ ▪ Introduction Theory of imperfect competition Monopolistic competition and trade Introduction ▪ We focus on internal econonomies of scale that are typical for imperfect competition. ▪ Now large firms have a cost advantage over small firms, rendering the industry not competitive. ▪ The industry is therefore monopolistic or oligopolistic. Theory of imperfect competition • With imperfect competition, firms are aware that they can influence the price of their product ▪ They know that they can sell more only by reducing their price. ▪ Each firm considers itself to be a price setter, choosing the price of its product, rather than a price taker ▪ Some examples of imperfectly competitive market structure are those of monopoly, oligopoly and monopolistic competition ▪ Oligopoly ▪ What is an oligopolististic market structure? There are several firms, each of which is large enough to affect prices, but none with an uncontested monopoly. ▪ Strategic interactions between oligopolists Each firm decides its own actions, taking into account how its decision might influence its rival’s actions -> problems of interdependence ▪ Cooperation among oligopolists Monopolistic competition and trade • Monopolististic competition = a special case of oligopoly o Two key assumptions are made to get around the problem of interdependence: ▪ Each firm is assumed to be able to differentiate its product from its rivals ▪ Each firm is assumed to take the prices charged by its rivals as given (there is competition but each firm acts as a monopolist) 58 o • Are there any monopolistically competitive industries in the real world? ▪ Some industries may be reasonable approximations (e.g., the automobile industry in Europe) ▪ The main appeal of the monopolistic competition model is not its realism, but its simplicity and the fact that it can illustrate how all countries can gain from trade Market equilibrium: o All firms in the industry are symmetric ▪ o 3 steps to determine the average price (P) and the number of firms (n): ▪ ▪ ▪ • The demand and cost function is the same for all firms We derive a relationship between the number of firms and the average cost of a typical firm. We derive a relationship between the number of firms and the price each firm charges. We derive the equilibrium number of firms and the average price that firms charge. (1) The number of firms and average cost o The upward sloping CC curve tells us that the more firms are present, the higher the average cost of each firm will be (if the number of firms increases, each firm will sell less so firms will not be able to move down their average cost curve) • • (2) The number of firms and the price o The downward-sloping PP curve shows that the more firms are present, the lower the price of each firm will be o (the more firms, the more competition each firm faces) (3) Equilibrium number of firms and price 59 • • The monopolistic competition model can be used to show how trade leads to: o A lower average price due to scale economies o The availability of a greater variety of goods due to product differentiation o Imports and exports within each industry (intra-industry trade) Graphically: effects of an increase in market size (because of trade): o PP-curve does not change o CC-curve changes 60 • • • Internal scale effects and comparative advantage combined: what is the trade pattern? Assumptions: ▪ 2 countries: Home (the capital-abundant country) and Foreign. ▪ 2 industries: manufactures (the capital-intensive industry) and food. ▪ Neither country is able to produce the full range of manufactured products by itself due to economies of scale. Main differences between inter-industry and intra-industry trade: ▪ Inter-industry trade reflects comparative advantage, whereas intra-industry reflects scale effects. ▪ The pattern of intra-industry trade itself is unpredictable, whereas that of inter-industry trade is determined by underlying differences between countries. ▪ The relative importance of intra-industry and inter-industry trade depends on how similar countries are. ▪ No income effects if intra-industrial trade, as opposed to inter-industry trade in the HO model 61 • • The Significance of Intraindustry Trade ▪ About one-fourth of world trade consists of intra-industry trade. ▪ Intra-industry trade plays a particularly large role in the trade in manufactured goods among advanced industrial nations, which accounts for most of world trade. Why Intraindustry Trade Matters ▪ Intraindustry trade allows countries to benefit from larger markets (extra benefits of trade apart from the effects of comparative advantage). ▪ Gains from intraindustry trade will be large when economies of scale are strong and products are highly differentiated (little or no income effects). Chapter 9: Instruments of trade policy ▪ ▪ Instruments of trade policy Costs and benefits of different instruments ▪ Tariff ▪ Export subsidy ▪ Other instruments Instruments of trade policy • Tariff barriers o Tariffs are taxes levied on goods that cross borders: ▪ Specific tariffs • ▪ Ad valorem tariffs • o Taxes that are levied as a fixed charge for each unit of goods imported Taxes that are levied as a fraction of the value of the imported goods Export subsidies are given by a government to an exporting firm; can also be specific or ad valorem 62 • Non-tariff barriers o Import quotas: limit the quantity of imports o ‘Voluntary’ Export restraints: limit the quantity of exports Costs and benefits of different instruments: Tariff • Assumptions: o Two countries (Home and Foreign) o 1 good o No transportation costs o Suppose that in the absence of trade the price of the good at H exceeds the corresponding price at F This implies that shippers begin to move the good from F to H such that the price in F increases and in H decreases • To determine the world price (Pw) and the quantity of trade (Qw), two curves are defined: o Home import demand curve ▪ o Shows the maximum quantity of imports the Home country would like to consume at each price of the imported good. • That is, the excess of what Home consumers demand over what Home producers supply: MD = D(P) – S(P) Foreign export supply curve ▪ Shows the maximum quantity of exports Foreign would like to provide the rest of the world at each price. • That is, the excess of what Foreign producers supply over what foreign consumers demand: XS = S*(P*) – D*(P*) 63 • Some useful definitions: o The terms of trade is the relative price of the exported good expressed in units of the imported good (PEX/PIM ) o A small country is a country that cannot affect its terms of trade no matter how much it trades with the rest of the world o The tariff always equals the difference between domestic and foreign prices: PT - PT* = t the level of these prices depends on the fact whether the tariff is small or rather large 64 country installing the • We assume the importing country to be a large country and there is a specific tariff of “t” Euro The price for importers in a large country becomes: PT - PT* = t (where PT* < PW) • • • • • • In the absence of tariff, the world price of the good (Pw) would be equalized in both countries. With the tariff in place, the price of the good rises at Home and falls at Foreign. o In Home: producers supply more and consumers demand less due to the higher price, so that fewer imports are demanded. o In Foreign: producers supply less and consumers demand more due to the lower price, so that fewer exports are supplied. o Thus, the total volume traded declines due to the imposition of the tariff. The increase in the domestic Home price is less than the tariff, because part of the tariff is reflected in a decline in Foreign’s export price. A tariff raises the price of a good in the importing country and lowers it in the exporting country. As a result of these price changes: o Consumers lose in the importing country and gain in the exporting country o Producers gain in the importing country and lose in the exporting country o Government imposing the tariff gains revenue To measure and compare these costs and benefits, we need to define consumer and producer surplus. 65 • Measuring the Cost and Benefits o Is it possible to sum consumer and producer surplus? ▪ o We can (algebraically) sum consumer and producer surplus because any change in price affects each individual in two ways: • As a consumer • As a worker We assume that at the margin a dollar’s worth of gain or loss to each group is of the same social worth. 66 • The net welfare effect of a tariff on national welfare in a large country: Loss for consumers = - (a + b + c + d) + gain for producers = + a + gain for government = + c + e -------------------------------------------------------= - (a + b + c + d) + a + c + e = - (b + d) + e Net effect: ambiguous because depends on (b+d) < e or (b+d) > e • The areas of the two triangles b and d measure the loss to the nation as a whole (efficiency loss) and the area of the rectangle e measures an offsetting gain (terms of trade gain). o The efficiency loss arises because a tariff distorts incentives to consume and produce. ▪ Producers and consumers act as if imports were more expensive than they actually are. ▪ Triangle b is the production distortion loss and triangle d is the consumption distortion loss. o The terms of trade gain arises because a tariff lowers foreign export prices (PEX/PIM ) o If the terms of trade gain is greater than the efficiency loss, the tariff increases welfare for the importing country. • What if we assume a small country? o The domestic price increases by less than the tariff because part of the tariff is ‘transferred’ to the foreign country ▪ If the home country is a small country, it cannot ‘transfer’ anything abroad and the domestic price increase will equal the tariff The price for importers in a small country is: PT - PW = t (where PT* = PW) 67 o o Note that a small country can never improve its terms of trade such that the welfare impact of a tariff for a small country can never be positive Make the graphical welfare analysis for a small country on your own Costs and benefits of different instruments: Export subsidy ▪ A payment by the government to a firm or individual that ships a good abroad ▪ ▪ ▪ The firm exports to the point where the domestic price PS equals the foreign price PS* plus the export subsidy (PS - PS* = s) Analysis for a large country ▪ An export subsidy increases the price in the exporting country (from Pw to Ps) and decreases the price (from Pw to Ps*) in the importing country ▪ Since the price in the importing country decreases from Pw to Ps*, the price increase in the exporting country is smaller than the subsidy ▪ An export subsidy decreases the terms of trade (PEX /PIM) ▪ An export subsidy always implies larger costs than benefits Make your own analysis for a small country 68 ▪ The net effect of an export subsidy on the national welfare in a large country: loss for consumers = - (a + b) + gain for producers = + a + b + c + loss for government = - (b + c + d + e + f + g) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------= - (b + c + d + e + f + g) + c = - (b + d) – (e + f + g) What effects does this equation represent? Costs and benefits of different instruments: Other instruments (1) Import quota o An import quota is a direct restriction on the quantity of a good that is imported. o The restriction is usually enforced by issuing licenses to some group of individuals or firms. o An import quota always raises the domestic price of the imported good. o License holders are able to buy imports and resell them at a higher price in the domestic market. o Welfare analysis of import quotas versus of that of tariffs ▪ The difference between a quota and a tariff is that with a quota the government receives no revenue. ▪ In assessing the costs and benefits of an import quota, it is crucial to determine who gets the rents. (2) Voluntary export restraint (VER) o A voluntary export restraint (VER) is an export quota administered by the exporting country. o VERs are imposed at the request of the importer and are agreed to by the exporter to forestall other trade restrictions. o Welfare analysis? A VER is exactly like an import quota where the licenses are assigned to foreign governments and is therefore very costly to the importing country. (3) Local Content Requirements (4) Export credit subsidies o A form of a subsidized loan to the buyer of exports o Welfare analysis idem export subsidies (5) National procurement (6) Red-tape barriers 69 Chapter 10: Political economy of trade policy • • Why do governments not always base their policy on economists’ cost-benefit calculations? o Why opt for free trade? o Why deviate from free trade? International trade agreements Why do governments not always base their policy on economists’ cost-benefit calculations?: Why opt for free trade? 1) Free trade increases efficiency (certainly for a small country) Cfr. Chapter 9: analysis of tariff for a small country; free trade avoids efficiency losses and thus increases welfare Note that since tariffs are already very low for most countries, extra free trade will not increase welfare that much 70 2) Extra benefits of free trade (figures Table 10.1 may be an underestimation): Free trade allows countries to exploit scale economies Cfr. Chapter 8: scale economies lead to lower prices and more varieties for consumers Free trade stimulates learning and innovating ▪ Only the best and most efficient firms can survive ▪ Countries can learn from each other; especially important for developing countries 3) More trade reduces rent-seeking Rent seeking = investing time and money to obtain quota rights (and the profits they imply) 4) Political argument for free trade Trade policies in practice are dominated by special-interest politics rather than consideration of national costs and benefits. Why do governments not always base their policy on economists’ cost-benefit calculations?: Why deviate from free trade? 1) Infant industry argument (Chapter 8) 2) Terms of trade argument (Chapter 9) For a large country (that is, a country that can affect the world price through trading), a tariff lowers the price of imports and generates a terms of trade benefit. ◼ This benefit must be compared to the costs of the tariff (production and consumption distortions). It is possible that the terms of trade benefits of a tariff outweigh its costs. ◼ Therefore, free trade might not be the best policy for a large country. 71 Optimal tariff: ◼ Zero for a small country ◼ Always less than the prohibitive tariff 3) Domestic market failure argument Producer and consumer surplus do not properly measure social costs and benefits. ◼ Consumer and producer surplus ignore domestic market failures such as: Unemployment or underemployment of labor Technological spillovers from industries that are new or particularly innovative Environmental externalities A tariff may raise welfare if there is a marginal social benefit to production of a good that is not captured by producer surplus measures. 72 The domestic market failure argument against free trade is a particular case of the theory of the second best. ◼ The theory of the second best states that a hands-off policy is desirable in any one market only if all other markets are working properly. If one market fails to work properly, a government intervention may actually increase welfare. How Convincing Is the Market Failure Argument? ◼ There are two basic arguments in defense of free trade in the presence of domestic distortions: Domestic distortions should be corrected with domestic (as opposed to international trade) policies Market failures are hard to diagnose and measure International trade agreements ◼ Since 1930’s tariffs and nontariff barriers to trade were gradually removed ◼ How was the removal of tariffs politically possible? The postwar liberalization of trade was achieved through international negotiation. It is easier to lower tariffs as part of a mutual agreement than to do so as a unilateral policy because: ◼ It helps mobilize exporters to support freer trade. ◼ It can help governments avoid getting caught in destructive trade wars. First bilateral negotiations (since 1930’s) The multilateral tariff reductions since World War II have taken place under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) – now called WTO The GATT-WTO system prohibits the imposition of: ◼ Export Subsidies (except for agricultural products) ◼ Import quotas (except when imports threaten “market disruption”) ◼ Tariffs (any new tariff or increase in a tariff must be offset by reductions in other tariffs to compensate the affected exporting countries) WTO engages in Trade rounds where a large group of countries get together to negotiate a set of tariff reductions and other measures to liberalize trade. ◼ Now also services + TRIPS ◼ Dispute settlement (decisions within 12 months; WTO can allow counter measures) 73 ◼ Doha round: why not a success? • Tariffs have already decreased a lot, politically sensitive sectors remain • Estimated profits are small and even negative for some countries GATT/WTO assume a non-discriminatory decrease in tariffs The GATT-WTO, through the principle of non-discrimination called the “most favored nation” (MFN) principle, prohibits such agreements. ◼ The formation of preferential trading agreements is allowed if they lead to free trade between the agreeing countries. ◼ Preferential Trade Agreements (PTA’s) can lead to trade creation (+) and trade diversion (-) -> ‘Stumbling block’ or ‘stepping stone’ for free trade? 74 Chapter 12: Controversies in trade policy ▪ ▪ Argument for trade protection: market failures ▪ Externalities ▪ Strategic trade policy with imperfect competition Arguments concerning trade and people ▪ Trade and low wages ▪ Trade and environment ▪ Trade and culture Argument for trade protection: market failures: Externalities ▪ First argument for trade protection ▪ Firms realize that if they invest in technology, they risk their knowledge to be copied ▪ Investments in technology create positive externalities for other firms ▪ The costs are for one party, the benefits for more parties ▪ The marginal social benefit of the investment cannot be measured by the producer surplus ➔ Governments should subsidize these high tech firms in order to stimulate them to innovate ▪ Possible problems of such a subsidy: ▪ Defining the ‘right’ industry ▪ Can be introduced in a simpler way through taxes (e.g. allowing firms to deduct investments from taxes) ▪ Correct estimation of externalities ▪ Externalities also happen outside country borders Argument for trade protection: market failures: Strategic trade policy with imperfect competition ▪ ▪ Second argument for trade protection Because of trade protection, oligopoly profits can be transferred to the own country o Brander-Spencer analysis: ▪ 2 airplane constructors: Airbus (EU) and Boeing (VS) ▪ Will they each build a new plane? This will depend on the decision of their competitor (game theory) ▪ Suppose there are large fixed costs such that if they both decide to produce the average costs remain very high (because of the limited production) such that both producers suffer a loss ▪ Who will start up production first? The government can influence this game by giving subsidies 75 ▪ Trade policy can attract oligopoly profits to the country (e.g: Airbus realizes large profits thanks to a relative small subsidy) ▪ Possible problems of such a policy: o One often does not have the correct information of all firms (e.g. correct costs and benefits) o If all countries do this, we end up in a very expensive trade war o Strategic trade policy can be influenced by strong lobby groups Arguments concerning trade and people: Trade and low wages ▪ Rich countries often import from poorer countries with lower wages and bad working conditions ▪ Lower wages: ▪ ▪ Ricardo and HO illustrate that without trade wages would be even lower Bad working conditions ▪ Often working conditions in exporting firms within developing countries are better than in domestic firms within developing countries ▪ How improve working conditions? ▪ International labour standards but this can be very expensive for developing countries – hence their resistence 76 Arguments concerning trade and people: Trade and environment ▪ Does trade have a negative impact on the environment? ▪ ▪ Depends on the level of development: Kuznets curve Should international environmental standards be introduced? ▪ Cfr. International labour standards: developing countries are not in favour because of higher costs ▪ Problem pollution havens Arguments concerning trade and people: Trade and culture ▪ Does trade destroy culture? 77