Karen Engle - The Grip of Sexual Violence in Conflict Feminist Interventions in International Law-Stanford University Press (2020) (1)

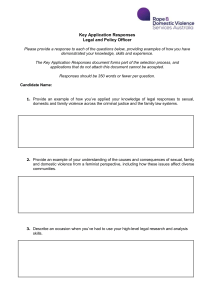

advertisement