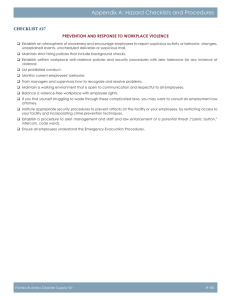

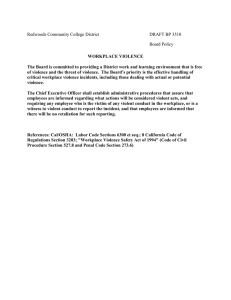

1 Policy Brief: Violence in the Social Work Profession Loyola University Chicago School of Social Work SOWK 602: Health and Behavioral Health Policy and Systems February 28, 2022 2 Dear Senators Tammy Duckworth and Dick Durbin: Executive summary The content of this brief covers the ongoing issue of violence that takes place in social service and healthcare settings across Illinois. Especially among social workers, instances of violence that happen in the workplace and out in the field threaten the safety and stability of this profession. This brief will provide an overview of the issue and how that has manifested in a single case study which had taken place in South Carolina. The findings of the study provide the harrowing data on the issues social workers have faced while working, and how prepared they felt to face the challenges. After, there will be a review of two of the most applicable guidelines and existing policy(s) that are related to protecting social workers on the job and in the office, and what that entails. The policy in this discussion will touch on funding for the protection prevention plans needed, and the role that policy plays in addressing this issue. Next, the brief presents a short discussion of the options for change that are available, and how each one impacts the implementation of preventative safety measures in health and service settings, as well as the potential for further development in policy adherence. After that, there will be a critical analysis of the policy options, and how each plays a part in contributing to safety measures and information created to protect social workers and other healthcare workers in the field. Finally, there will be the recommendation of which policy option presents as a critical component to protecting social workers and a description of why that is the case. The problem Given the variety and exposure to several settings that could make social workers vulnerable, it is important to take into consideration some precautions and trainings that can be done before 3 social workers and health professionals venture out into the field. While there are only a few existing policies and guidelines that give social workers some protection and guidance, this brief takes a look at some of the gaps that show when experienced in real life. In other words, the implementation of protective measures and enhanced awareness, understanding, and training that social workers have access to, prior to, and when working out in the field should be increased on a material level. Statistics have shown that in 2005, 14.7% of social workers had experienced a physical assault by their clients, while 30.2% had claimed to have been assaulted at some time throughout their career as a social worker (Stuck et al., 2014). The root cause of this violence may be inherent to the work that social workers do, and can be seen as a manifestation of psychological distress, or heavy resistance to treatment by clients. This risk and reality of working in social work can be applicable to many of the different sectors, practices and organizations, and therefore, it is emphasized in the literature, that organizations should take care to ensure their clinicians are trained with regards to specific safety procedures and take a variety of precautions within their workspace and without. This can be done as a part of the licensing process as well. A study was done in South Carolina which surveyed 554 social workers on their experiences with violence in their roles as well as the amount of training they received. The results concluded that 27% of the sample had experienced bullying or harassment within their workplace, while 44.4% participated in behavior that was unsafe (Guest., 2021). This could include working alone, without means of contacting another person, or without coworkers knowing where you are. 32.8% of this sample had experienced verbal assaults or threats, 16% had experienced physical assault, and 12% witnessed violence in the workplace (Guest., 2021). 4 Finally, 69.5% of the sample claimed to have received training to handle violent behavior, but only 8% stated they were prepared to handle violence they were faced with (Guest., 2021). These findings implicate that there is little regulation surrounding engagement in safety training and de-escalation techniques with clients. This could be an effect of ongoing budget cuts and at times, a lack of resources needed to meet client needs. The four main areas identified that need to be developed include awareness raising, training, education, and social work policy and guidelines (Guest., 2021). Safety measures that can be considered include the arrangement of the clinical office so that the door can be seen from where the social worker and/or client is sitting, the integration of a panic button, and creating concrete protocols for managing a threat in the workplace or a field setting (Guest., 2021). The persistent enforcement of concrete ideas for workplace safety such as safe access to vehicles, mobile phones, risk assessments for home and field visits, and someone to know where a worker is and when they are estimated to return is critical, and can make a difference should a violent encounter occur (Guest., 2021). Pre-existing Policies As it stands currently, there are two main pieces that include guidelines from the NASW and policy S. 4412 named The Protecting Social Workers and Health Professionals from Workplace Violence Act, that aim to support the protection of social service workers. The NASW guidelines state that they are meant for development into policy and practice, as well as to compare against the current workplace safety measures and culture (Newhill & Hagan, 2010). It specifies that the generalizability of the guidelines developed, should be evolved into practices and precautions that can be specific across different settings (Newhill & Hagan, 5 2010). Encouragement and acknowledgement is made so that regulations, licensing, and resources are perpetuated by the content of the guidelines to enhance safety for social workers in their workplace (Newhill & Hagan, 2010). The guidelines include eleven standards. These standards consist of the organizational culture of safety and security standard, prevention, office safety, use of safety technology, use of mobile phones, risk assessments for field visits, transporting clients, comprehensive reporting practices, post-incident reporting and response, safety training, and student safety (Newhill & Hagan, 2010). These areas are the most prominent areas that should be considered when developing workplace safety measures. While the NASW does a great job of considering and integrating all these factors into workplace safety for social workers, it is clear that the work to implement this information is needed to adjust the statistics of violent experiences that are reported by social workers and healthcare workers. Furthermore, the Protecting Social Workers and Health Professionals from Workplace Violence Act, lays a solid foundation for the much needed funding of workplace safety measures for social service organizations. The bill states that they will award grants to states, Indian tribes, tribal organizations, and urban Indian organizations so that safety measures can be taken into account and implemented (Sinema, 2022). Some of the features mentioned to be supported include safety equipment, tracking devices, panic buttons, and locators. Additional investments might include self defense trainings, security cameras, and learning of deescalation strategies of conflict competency, along with the involvement of law enforcement. In order to obtain funding, there is an application process and grant writing that goes into it, which 6 is required to outline the specific need and developments the organization plans will make (Sinema, 2022). Finally, as an existing act in the state of Illinois, the 225 ILCS 20/—Professions, Occupations, and Business Operations Clinical Social Work and Social Work Practice Act comes forth as a statute to uphold high standards of the social work profession in our state (Illinois General Assembly, n.d.). This piece of legislature places a duty upon social workers to be educated, trained, and qualified to provide quality services as the practice has a strong impact upon public health, safety, and welfare (Illinois General Assembly, n.d.). We would like to point out, that just as regulation and importance is placed upon having competent social workers who can assist all types of people of the public, there should be an equal emphasis on the safety and implementation of protective measures, that are strictly in place to protect the welfare of those in the social work profession. This is necessary specifically in our state of Illinois, in order to carry out consistent and optimal functioning within the social work profession. Identification of Options Both of the presented pieces of formal literature created to protect social workers in the field pose the framework and provide the resources to bring more safety into the practice. With the way this information currently stands there are three options. The first is to keep the guidelines and the policy to protect social workers in place, and maintain the status quo within social work as it currently stands. This would not be the best option as social workers will continue to experience the consequences of diminished safety protocols. The second option would be to consider providing an online or in-person training for social and healthcare workers so that they 7 can directly become aware of risk when working out in the field and how to mitigate it. This option would be favorable in raising awareness and potentially having workers organize a response that is exclusive to their practice. However, that aspect is not guaranteed. The third and most supportive option would be to not only implement in-person trainings to learn about risk, but to also include self defense, in-office safety equipment, assessments, and protocols in place that organizations are committed to carry out. This third option takes a holistic approach to the protection of health and social workers. The point here is that although there is a level of resources available to protect clinicians, it may be that organizations are overlooking the grant opportunity and NASW guidelines. Every organization should evaluate the practices that they engage in, and do a risk assessment of the activities involved. From that point, there can be a better idea of what safety looks like in their organization and the kinds of tools that are needed to protect workers on home visits, out in the field, and in the office. These measures may also be built into training for licensing acquisition and renewal. It may not always be possible that every instance of violence can be prevented, but the resources available present the opportunity and actions needed to reduce the prevalence of workplace and field violence in social service and health professions. Critical Analysis of Policy Options In 2019, the first official policy to protect health and social service workers was put into place and this was the Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act. This is the policy that requires health and social service workers to create and employ safety procedures in the workplace. The literature reads that it took seven years for this bill to pass 8 since the reception of its acknowledgement in 2013 (After 7-year effort…, 2022). The statement made is that prevention plans make workplace violence events more foreseeable. The bill has a focus towards protecting women who occupy a large amount of the health and social service workers we see. The bill recognizes workplace safety as a human right and targets employers to uphold their due diligence in protecting their workplace (After 7-year effort…, 2022). It urges employers to investigate violence that takes place in the workplace, hazards, and risks as soon as they are identified. It also protects workers against discrimination and retaliation for reporting these incidents, and requires employers to keep records of incidents, education, and training that take place (After 7-year effort…, 2022). A study from 2016 found that 70% of nonfatal attacks that took place in the workplace were in health care and social service sectors (After 7-year effort…, 2022). Additionally, the rate of violence that occurs in health care settings was found to be 12 times the amount of the rates of these occurrences in other settings(After 7-year effort…, 2022). This bill targets one of the main stakeholders which is the employer of all health and social service organizations to make sure that protocols to avoid and curb workplace violence take place (H.R.1309, 2019). They are a central stakeholder because their facilities and reputation are on the line when these events take place. Another central stakeholder would be the employees, who’s lives and wellbeing are at stake in some of these roles. Finally, clients can be seen as a stakeholder, who may be protected from self inflicted harm by the introduction of this policy. My Recommendation 9 The Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act plays a critical role in the implementation of safety prevention plans, and tools to keep social and healthcare workers from harm. While the NASW guidelines provide the specific framework for the safety measures that should be taken, The Protecting Social Workers and Health Professionals from Workplace Violence Act provides the monetary assistance to states and organizations who apply for it. This bill was so popular it passed again in May of 2022 with a higher level of bipartisan support (Following deadly shooting of home health…, 2022). While this bill and the NASW guidelines are critical to bringing more workplace safety to health and social service workers, the reinforcement of the Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act is a critical piece of legislation that is on the brink of protecting many in healthcare, and should be deliberately executed in all social work settings to make it a safer workplace for all. This bill was passed in the house twice, and was brought to the senate in May of 2022, where it currently awaits a vote (Following deadly shooting of home health…, 2022). It is my recommendation that this bill become a requirement in all social service organizations in the state of Illinois, in order to protect social workers from unexpected violence. That way, we will see required safety measures and practices become implemented in social work organizations across Illinois—that when recorded and maintained, can serve their purpose in protecting social workers over time. I hope that following this brief you will better understand the risk, and strongly support the passing of this bill through the senate when it comes time. Sincerely, Illinois Social Workers 10 References After 7-year effort, House votes to pass rep. Courtney's Bill to curb workplace violence against health care and Social Service Workers. Congressman Joe Courtney. (2022, June 29). Retrieved February 11, 2023, from https://courtney.house.gov/media-center/pressreleases/after-7-year-effort-house-votes-pass-rep-courtneys-bill-curb-workplace Following deadly shooting of home health care worker, rep. Courtney urges the Senate to bring the Bipartisan Workplace Violence Prevention Bill to a vote. Congressman Joe Courtney. (2022, December 9). Retrieved February 11, 2023, from https://courtney.house.gov/ media-center/press-releases/following-deadly-shooting-home-health-care-worker-repcourtney-urges Guest, A. (2021, July). Worker protection peer-reviewed social worker safety - ASSP. Retrieved February 11, 2023, from https://www.assp.org/docs/default-source/psj-articles/ f1guest_0721.pdf?sfvrsn=f9139947_2 H.R.1309 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): Workplace violence prevention ... (2019, November 21). Retrieved February 11, 2023, from https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/ house-bill/1309 Illinois General Assembly. (n.d.). PROFESSIONS, OCCUPATIONS, AND BUSINESS OPERATIONS (225 ILCS 20/) Clinical Social Work and Social Work Practice Act. 225 ILCS 20/ clinical social work and social work practice act. Retrieved February 28, 2023, from https://ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/ilcs3.asp?ActID=1295&ChapterID=24 11 Newhill, C., & Hagan, L. (2010). Violence in Social Work Practice. Retrieved February 11, 2023, from https://www.socialworkers.org/assets/secured/documents/sections/mental_health/ newsletters/SEC-NL-26815.MH-NL.pdf Sinema, K. (2022, June 15). S. 4412. Retrieved February 11, 2023, from https:// www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-117hr2617enr/pdf/BILLS-117hr2617enr.pdf Stuck, E., Skolnik-Acker, E., Sankar, S., Keaney, B., Fisher, B., Perlstein, J., & Trust, C. (2014, January 20). Workplace Safety - National Association of Social Workers - NASW-MA. Retrieved February 11, 2023, from https://www.naswma.org/page/_Test_SafetyLanding