Cognition-exploring-the-science-of-the-mind- Chapter 1 – Hints and Tips

advertisement

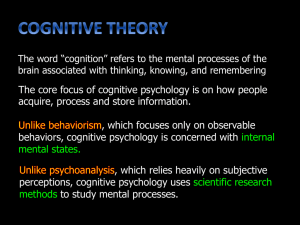

1. What is cognition? Cognitive psychology is concerned with how people remember, pay attention, and think. The importance of all these issues arises partly from the fact that most of what we do, say, and feel is guided by things we already know. One example is our comprehension of a simple story, which turns out to be heavily influenced by the knowledge we supply. 2. What does cognitive psychology look at in a general sense? This field is sometimes defined as the scientific study of the acquisition, reten- tion, and use of knowledge. We’ve now seen, though, that “knowledge” (and hence the study of how we gain and use knowledge) is relevant to a huge range of concerns. Our self-concept, it seems, depends on our knowledge (and, in particular, on our memory for various episodes in our past). Our emotional adjustments to the world rely on our memories. Even our abil- ity to understand a simple story—or, presumably, our ability to understand any experience—depends on our supplementing that experience with some knowledge. The suggestion, then, is that cognitive psychology can help us understand capacities relevant to virtually every moment of our lives. Activities that don’t appear to be intellectual would collapse without the support of our cogni- tive functioning. 3. Why is memory so important for everyday life? You obviously rely on memory when you’re taking an exam—memory for what you learned during the term. Likewise, you rely on memory when you’re at the supermarket and trying to remember the cheesecake recipe so that you can buy the right ingredients. You also rely on memory when you’re reminiscing about childhood. Also, many (perhaps all) of your encounters with the world depend on your supplementing your experience with knowledge that you bring to the situation. “Betsy and Jacob” story Betsy wanted to bring Jacob a present. She shook her piggy bank. It made no sound. She went to look for her mother. Prior knowledge (a) that the things one gives as presents are often things bought for the occasion (rather than things already owned), (b) that buying things requires money, and (c) that money is sometimes stored in piggy banks. (d) that Betsy was a child (because few adults keep their money in piggy banks), (e) that children don’t keep track of how much money is in their banks, and (f) that piggy banks are made out of opaque material (and so a child can’t simply look into the bank to see what’s inside). Without these facts, Betsy’s shaking of the bank would make no sense. Similarly, you understood what it meant that the bank made no sound. That’s because you know (g) that it’s usually coins (not bills) that are kept in piggy banks, and (h) that coins make noise when they’re shaken. In a sense, then, without a memory, there is no self. Numerous memories sup- port our conception of who we are: We know whether we deserve praise for our good deeds or blame for our transgressions because we remember those good deeds and transgressions. We know whether we’ve kept our promises or achieved our goals because, again, we have the relevant memories. 4. How is a cognitive science similar to but still different from a criminal investigation? Of course, physicists (and other scientists) have a huge advantage over a police detective. If the detective has insufficient evidence, she can’t arrange for the crime to happen again in order to produce more evidence. (She can’t say to the robber, “Please visit the bank again, but this time don’t wear a mask.”) Scientists, in contrast, can arrange for a repeat of the “crime” they’re seeking to explain— they can arrange for new experiments, with new measures. Better still, they can set the stage in advance, to maximize the likelihood that the “culprit” (in our example, the electron) will leave useful clues behind. They can, for example, add new recording devices to the situation, or they can place various obstacles in the electron’s path. In this way, scientists can gather more and more data, including data crucial for testing the predictions of a particular theory. This prospect — of reproducing experiments and varying the experiments to test hypotheses — is what gives science its power. It’s what enables scientists to assert that their hypotheses have been rigorously tested, and it’s what gives scientists assurance that their theories are correct. 5. What is Introspection? Introspection, or “looking within,” to observe and record the content of our own mental lives and the sequence of our own experiences. 6. What do classical behaviourists study? The behaviorist perspective demands that we not talk about mental entities such as beliefs, memories, and so on, because these things cannot be studied directly and so cannot be studied scientifically. Yet it seems that these subjec- tive entities play a pivotal role in guiding behavior, and so we must consider them if we want to understand behavior. 7. What is the transcendental method? To use Kant’s transcendental method, you begin with the observable facts and then work backward from these observations. In essence, you ask: How could these observations have come about? What must be the underlying causes that led to these effects? This method, sometimes called “inference to best explanation,” is at the heart of most modern science. In each case, we begin with a particular performance — say, a prob- lem that someone solved—and then hypothesize a series of unseen mental events that made the performance possible. But we don’t stop there. We also ask whether some other, perhaps simpler, sequence of events might explain the data. In other words, we do more than ask how the data came about; we seek the best way to think about the data. 8. How did computer science contribute to cognitive science? In the 1950s a new approach to psychological explanation became available and turned out to be immensely fruitful. It soon became clear that com- puters were capable of immensely efficient information storage and retrieval (“memory”), as well as performance that seemed to involve decision making and problem solving. Psychologists were intrigued by these proposals and began to explore the possibility that the human mind followed processes and procedures similar to those used in computers. As a result, psychological data were soon being explained in terms of “buffers” and “gates” and “central processors,” terms borrowed from computer technology. This computer-based vocabulary allowed a new style of theorizing. Given a particular performance, say, in paying attention or on some memory task, one could hypothesize a series of information-processing events that made the performance possible. As we will see, hypotheses cast in these terms led psychologists to predict a broad range of new observations, and in this way both organized the available information and led to many new discoveries. 9. What was the Gestalt Movement’s contribution to modern psychology? Overall, the Gestalt psychologists argued that behaviors, ideas, and perceptions are organized in a way that could not be understood through a part-by-part, element- by-element, analysis of the world. Instead, they claimed, the elements take on meaning only as part of the whole — and therefore psychology needed to understand the nature of the “whole.” This position had many implications, including an emphasis on the role of the perceiver in organizing his or her experience. As we will see, this notion—that perceivers shape their own experience—is a central theme for modern cognitive psychology.