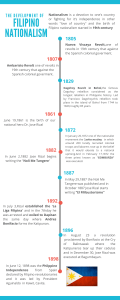

On January 20, 1872, two hundred Filipinos employed at the Cavite arsenal staged a revolt against the Spanish government’s voiding of their exemption from the payment of tributes. The Cavite Mutiny led to the persecution of prominent Filipinos; secular priests Mariano Gómez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora—who would then be collectively named GomBurZa—were tagged as the masterminds of the uprising. The priests were charged with treason and sedition by the Spanish military tribunal—a ruling believed to be part of a conspiracy to stifle the growing popularity of Filipino secular priests and the threat they posed to the Spanish clergy. The GomBurZa were publicly executed, by garrote, on the early morning of February 17, 1872 at Bagumbayan. The Archbishop of Manila refused to defrock them, and ordered the bells of every church to toll in honor of their deaths; the Sword, in this instance, denied the moral justification of the Cross. The martyrdom of the three secular priests would resonate among Filipinos; grief and outrage over their execution would make way for the first stirrings of the Filipino revolution, thus making the first secular martyrs of a nascent national identity. Jose Rizal would dedicate his second novel, El Filibusterismo, to the memory of GomBurZa, to what they stood for, and to the symbolic weight their deaths would henceforth hold: The Government, by enshrouding your trial in mystery and pardoning your co-accused, has suggested that some mistake was committed when your fate was decided; and the whole of the Philippines, in paying homage to your memory and calling you martyrs, totally rejects your guilt. The Church, by refusing to degrade you, has put in doubt the crime charged against you. THE REVOLUTIONARY GENERATION ON GOMBURZA • JOSE RIZAL’S LETTER TO MARIANO PONCE, 18 APRIL 1889— “Without 1872 there would not now be a Plaridel, a Jaena, a Sanciangco, nor would the brave and generous Filipino colonies exist in Europe. Without 1872 Rizal would now be a Jesuit and instead of writing the Noli Me Tangere, would have written the contrary. At the sight of those injustices and cruelties, though still a child, my imagination awoke, and I swore to dedicate myself to avenge one day so many victims. With this idea I have gone on studying, and this can be read in all my works and writings. God will grant me one day to fulfill my promise.” [via] • JOSE RIZAL’S LETTER TO MARIANO PONCE, 18 APRIL 1889— “If at his death Burgos had shown the courage of Gomez, the Filipinos of today would be other than they are. However, nobody knows how he will behave at that culminating moment, and perhaps, I myself, who preach and boast so much, may show more fear and less resolution than Burgos in that crisis. Life is so pleasant, and it is so repugnant to die on the scaffold, still young and with ideas in one’s head…” [via] • “RITUAL FOR THE INITIATION OF A BAYANI,” 1894— Document, via Jim Richardson, details the ritual to be followed when a Katipunan member with the rank of Soldier (Kawal) is to be elevated to the rank of Patriot (Bayani): “Presiding over the ritual, the Most Respected President (presumably Bonifacio himself) reflects on the martyrdom of the priests Burgos, Gomez and Zamora—a great wrong, he says, that tore aside the veil that had covered the eyes of the Tagalogs. Tracing the Katipunan’s political lineage a little further back, he also alludes to the movement for reforms that preceded the Cavite mutiny, mentioning specifically the newspaper El Eco Filipino, which was founded by Manuel Regidor (the brother of Antonio Ma. Regidor), Federico de Lerena (the brother-in-law of José Ma. Basa) and other liberal Filipinos in Madrid in 1871. Copies were sent to Manila but soon began to be intercepted, and people found in possession of the paper were liable to be arrested.” [via] • EMILIO JACINTO, “GOMEZ, BURGOS AT ZAMORA!” APRIL 30, 1896— Jim Richardson: “The day that Gomez, Burgos and Zamora were executed, writes Jacinto, was a day of degradation and wretchedness. Twenty-four years had since passed, but the excruciating wound inflicted that day on Tagalog hearts had never healed; the bleeding had never been staunched. Though the lives of the three priests had been extinguished that day, their legacy would endure forever. Their compatriots would honor their memory, and would seek to emulate their pursuit of truth and justice. As yet, Jacinto acknowledges, some were not fully ready to embrace those ideals, either because they failed to appreciate the need for solidarity and unity or because their minds were still clouded by the smoke of a mendacious Church. But those who could no longer tolerate oppression were now looking forward to a different way of life, to a splendid new dawn.” [via] RECALLING THE GOMBURZA • EDMOND PLAUCHUT, AS QUOTED BY JAIME VENERACION— The Execution of GomBurZa [via] Late in the night of the 15th of February 1872, a Spanish court martial found three secular priests, Jose Burgos, Mariano Gomez and Jacinto Zamora, guilty of treason as the instigators of a mutiny in the Kabite navy-yard a month before, and sentenced them to death. The judgement of the court martial was read to the priests in Fort Santiago early in the next morning and they were told it would be executed the following day… Upon hearing the sentence, Burgos broke into sobs, Zamora lost his mind and never recovered it, and only Gomez listened impassively, an old man accustomed to the thought of death. When dawn broke on the 17th of February there were almost forty thousand of Filipinos (who came from as far as Bulakan, Pampanga, Kabite and Laguna) surrounding the four platforms where the three priests and the man whose testimony had convicted them, a former artilleryman called Saldua, would die. The three priests followed Saldua: Burgos ‘weeping like a child’, Zamora with vacant eyes, and Gomez head held high, blessing the Filipinos who knelt at his feet, heads bared and praying. He was next to die. When his confessor, a Recollect friar , exhorted him loudly to accept his fate, he replied: “Father, I know that not a leaf falls to the ground but by the will of God. Since He wills that I should die here, His holy will be done.” Zamora went up the scaffold without a word and delivered his body to the executioner; his mind had already left it. Burgos was the last, a refinement of cruelty that compelled him to watch the death of his companions. He seated himself on the iron rest and then sprang up crying: “But what crime have I committed? Is it possible that I should die like this. My God, is there no justice on earth?” A dozen friars surrounded him and pressed him down again upon the seat of the garrote, pleading with him to die a Christian death. He obeyed but, feeling his arms tied round the fatal post, protested once again: “But I am innocent!” “So was Jesus Christ,’ said one of the friars.” At this Burgos resigned himself. The executioner knelt at his feet and asked his forgiveness. “I forgive you, my son. Do your duty.” And it was done. (Veneracion quotes Leon Ma. Guerrero’s The First Filipino: “We are told that the crowd, seeing the executioner fall to his knees, suddenly did the same, saying the prayers to the dying. Many Spaniards thought it was the beginning of an attack and fled panic-stricken to the Walled City.”) • LEON MA. GUERRERO, IN THE FIRST FILIPINO, ASIDE FROM CITING EDMOND PLAUCHUT, REVYE DES DEUX MONDES, MAY 15, 1877, WROTE: “Montero deserves a hearing because he had access to the official records. His account, in brief, is that the condemned men, in civilian clothes, were taken to the headquarters of the corps of engineers outside the city walls, where a death-cell had been improvised. Members of their families were allowed to visit them. The night before the execution, Gómez went to confession with an Augustinian Recollect (leaving a fortune of 200,000 to a natural son whom he had had before taking orders); Burgos to a Jesuit; Zamora, to a Vicentian. At the execution itself, Burgos is described as “intensamente pálido;” Zamora, as “afligidísmo;” and Gómez as “revelando en su faz sombría la ira y la desesperacíon.” The judgment was once more read to them, on their knees. Burgos and Zamora “lloraban amargamanete,” while Gòmez listened “con tranquilidad imperturbable. Ni un solo músculo de su cara se contrajó.” The order of execution, according to Montero, was Gómez, Zamora, Burgos and Saldúa last of all. He explains the panice saying it was the natives when a horse bolted: Burgos, thinking rescue was on the way, rose to his feet and had to be held down by the executioner. Montero denies both the anecdotes concerning Gómez and Burgos. It is fair to add that Montero seems to lose his composure in refuting Plauchut.” [The First Filipino. Guerrero, Leon Maria] The Cavite Mutiny of 1872 and GomBurZa Execution Written by HAROLD HISONA Friday, 31 August 2012 06:06 On the night of January 20, 1872, about 200 Filipino soldiers and workers in the Cavite arsenal rose in mutiny under the leadership of a certain Lamadrid, a Filipino sergeant. The mutineers had a secret understand with the Filipino soldiers in Manila for a concerted uprising, the signal being the firing of rockets for the walls of Intramuros. Unfortunately, the suburb of Sampaloc, in Manila, celebrated its fiesta that night with a brilliant display of fireworks. Thinking that the fireworks had been set off by the Manila troops, the Cavite plotters rose in arms. They killed their Spanish officers and took control of the arsenal. Government troops under Felipe Ginoves rushed to Cavite the following morning. A bloddy battle ensued. Many of the mutineers, including Lamadrid, were killed in the fighting. The survivors were subdued and take to Manila as prisoners. The Mutiny was magnified by the Spaniards into a "revolt" so as to implicate the Filipino priest-patriots. It was in reality just a mutiny of the Cavite soldiers and workers who had resented the government action in abolishing their old-time privileges, notable their exemption from the tribute and from forced labor. But Spanish writers alleged that it was a seditious revolt directed against Spanish rule and fomented by Fathers Burgos, Gomez and Zamora and by other Filipino leaders. This allegation was false, but it was accepted by the government authorities because it gave them a pretext to get rid of the Filipino leaders they did not like. Conviction and Execution of GomBurZa Immediately after the Cavite mutiny was suppressed, many Filipino patriots were arrested and thrown in prison. Among these were the three priests—Fathers Gomez, Burgos, and Zamora, the three men who championed the cause of the Filipino priests who had not been receiving their due from the Spanish authorities. Talented and patriotic, they carried on the nationalist movement of Father Pedro Pelaez, who had perished in the Manila earthquake in 1863. Their movement was popularly called the Filipinization or secularization of the clergy because it advocated the equality of right between the native secular priests—priests who lived among the people—and the Spanish friars, who lived in religious communities separated from the towns and cities. At that time the Filipino priests were not allowed to hold high and profitable positions in the church because of their brown skin and Asian ancestry. After a farcical trial by a military court, Fathers Burgos, Gomez, and Zamora were sentenced to die by the garrote, a strangulation machine. The court verdict was approved by the harsh General Izquierdo, who then immediately asked Archbishop Gergorio Meliton Martinez of Manila to deprive them of their priestly robes before their execution. The archbishop denied this request, for he believed the three condemned priests were innocent. On the morning of February 17, 1872, the three priests were garroted to death at the Bagumbayan. This execution was a calamitous blunder of the Spanish authorities. The Filipinos deeply resented it, for they regard the three priests as the public martyrs of their fatherland. In their indignation, the Filipinos forgot their regional boundaries and differences and rallied as a united nation to fight the Spanish injustice. The blood of the martyrs of 1872 was thus the fertile seed of Filipino nationalism. Birth of Jose Rizal's Patriotism At the time of the three priests' martyrdom, Jose Rizal was an eleven-year-old boy in Calamba, Laguna. Paciano, his older brother, who was a student and friend of Father Burgos, told Jose the tragic story of the three priests' martyrdom. The young Jose was deeply impressed and swore to carry on the unfinished work of the three martyrs. His second novel, El Filibusterismo was dedicated to the memory of these three priests. His dedication read as follows: The Church, by refusing to degrade you (Archbishop refused to remove the priesthood robes), has placed in doubt the crime that has been imputed to you; the Government, by surrounding your trials with mystery and shadow, causes the belief that there was some error committed in fatal moments; and all the Philippines, by worshiping your memory and calling you martyrs, in no sense recognizes your culpability. Insofar, therefore, as your complicity in the Cavite mutiny is not clearly proved, as you may or may not have been patriots, and as you may or may not have cherished sentiments for justice and for liberty, I have the right to dedicate my work to you as victims of the evil which I undertake to combat. And while we await expectantly upon Spain someday to restore your good name and cease to be answerable for your death, let these pages serve as a tardy wreath and dried leaves over your unknown tombs, and let it be understood that everyone who, without clear proofs, attacks your memory stains his hands in your blood! Source:http://www.philippinealmanac.com/history/cavite-mutiny-1872-gomburzaexecution-18524.html THE TWO FACES OF THE 1872 CAVITE MUTINY By Chris Antonette Piedad-Pugay Two major events happened in 1872, first was the 1872 Cavite Mutiny and the other was the martyrdom of the three martyr priests in the persons of Fathers Mariano Gomes, Jose Burgos and Jacinto Zamora (GOMBURZA). However, not all of us knew that there were different accounts in reference to the said event. All Filipinos must know the different sides of the story—since this event led to another tragic yet meaningful part of our history—the execution of GOMBURZA which in effect a major factor in the awakening of nationalism among the Filipinos. 1872 Cavite Mutiny: Spanish Perspective Jose Montero y Vidal, a prolific Spanish historian documented the event and highlighted it as an attempt of the Indios to overthrow the Spanish government in the Philippines. Meanwhile, Gov. Gen. Rafael Izquierdo’s official report magnified the event and made use of it to implicate the native clergy, which was then active in the call for secularization. The two accounts complimented and corroborated with one other, only that the general’s report was more spiteful. Initially, both Montero and Izquierdo scored out that the abolition of privileges enjoyed by the workers of Cavite arsenal such as nonpayment of tributes and exemption from force labor were the main reasons of the “revolution” as how they called it, however, other causes were enumerated by them including the Spanish Revolution which overthrew the secular throne, dirty propagandas proliferated by unrestrained press, democratic, liberal and republican books and pamphlets reaching the Philippines, and most importantly, the presence of the native clergy who out of animosity against the Spanish friars, “conspired and supported” the rebels and enemies of Spain. In particular, Izquierdo blamed the unruly Spanish Press for “stockpiling” malicious propagandas grasped by the Filipinos. He reported to the King of Spain that the “rebels” wanted to overthrow the Spanish government to install a new “hari” in the likes of Fathers Burgos and Zamora. The general even added that the native clergy enticed other participants by giving them charismatic assurance that their fight will not fail because God is with them coupled with handsome promises of rewards such as employment, wealth, and ranks in the army. Izquierdo, in his report lambasted the Indios as gullible and possessed an innate propensity for stealing. The two Spaniards deemed that the event of 1872 was planned earlier and was thought of it as a big conspiracy among educated leaders, mestizos, abogadillos or native lawyers, residents of Manila and Cavite and the native clergy. They insinuated that the conspirators of Manila and Cavite planned to liquidate high-ranking Spanish officers to be followed by the massacre of the friars. The alleged pre-concerted signal among the conspirators of Manila and Cavite was the firing of rockets from the walls of Intramuros. According to the accounts of the two, on 20 January 1872, the district of Sampaloc celebrated the feast of the Virgin of Loreto, unfortunately participants to the feast celebrated the occasion with the usual fireworks displays. Allegedly, those in Cavite mistook the fireworks as the sign for the attack, and just like what was agreed upon, the 200-men contingent headed by Sergeant Lamadrid launched an attack targeting Spanish officers at sight and seized the arsenal. When the news reached the iron-fisted Gov. Izquierdo, he readily ordered the reinforcement of the Spanish forces in Cavite to quell the revolt. The “revolution” was easily crushed when the expected reinforcement from Manila did not come ashore. Major instigators including Sergeant Lamadrid were killed in the skirmish, while the GOMBURZA were tried by a court-martial and were sentenced to die by strangulation. Patriots like Joaquin Pardo de Tavera, Antonio Ma. Regidor, Jose and Pio Basa and other abogadillos were suspended by the Audencia (High Court) from the practice of law, arrested and were sentenced with life imprisonment at the Marianas Island. Furthermore, Gov. Izquierdo dissolved the native regiments of artillery and ordered the creation of artillery force to be composed exclusively of the Peninsulares. On 17 February 1872 in an attempt of the Spanish government and Frailocracia to instill fear among the Filipinos so that they may never commit such daring act again, the GOMBURZA were executed. This event was tragic but served as one of the moving forces that shaped Filipino nationalism. A Response to Injustice: The Filipino Version of the Incident Dr. Trinidad Hermenigildo Pardo de Tavera, a Filipino scholar and researcher, wrote the Filipino version of the bloody incident in Cavite. In his point of view, the incident was a mere mutiny by the native Filipino soldiers and laborers of the Cavite arsenal who turned out to be dissatisfied with the abolition of their privileges. Indirectly, Tavera blamed Gov. Izquierdo’s cold-blooded policies such as the abolition of privileges of the workers and native army members of the arsenal and the prohibition of the founding of school of arts and trades for the Filipinos, which the general believed as a cover-up for the organization of a political club. Commented [ju1]: In corroboration with Izguerido and Montero’s acct of how the mutiny begun On 20 January 1872, about 200 men comprised of soldiers, laborers of the arsenal, and residents of Cavite headed by Sergeant Lamadrid rose in arms and assassinated the commanding officer and Spanish officers in sight. The insurgents were expecting support from the bulk of the army unfortunately, that didn’t happen. The news about the mutiny reached authorities in Manila and Gen. Izquierdo immediately ordered the reinforcement of Spanish troops in Cavite. After two days, the mutiny was officially declared subdued. Tavera believed that the Spanish friars and Izquierdo used the Cavite Mutiny as a powerful lever by magnifying it as a full-blown conspiracy involving not only the native army but also included residents of Cavite and Manila, and more importantly the native clergy to overthrow the Spanish government in the Philippines. It is noteworthy that during the time, the Central Government in Madrid announced its intention to deprive the friars of all the powers of intervention in matters of civil government and the direction and management of educational institutions. This turnout of events was believed by Tavera, prompted the friars to do something drastic in their dire sedire to maintain power in the Philippines. Commented [ju2]: The event existed to be a loop hole to get what they wanted: for Filipinos to be under their restraint or manipulation to avoid dethronement and secularization of the government and church leaders Meanwhile, in the intention of installing reforms, the Central Government of Spain welcomed an educational decree authored by Segismundo Moret promoted the fusion of sectarian schools run by the friars into a school called Philippine Institute. The decree proposed to improve the standard of education in the Philippines by requiring teaching positions in such schools to be filled by competitive examinations. This improvement was warmly received by most Filipinos in spite of the native clergy’s zest for secularization. The friars, fearing that their influence in the Philippines would be a thing of the past, took advantage of the incident and presented it to the Spanish Government as a vast conspiracy organized throughout the archipelago with the object of destroying Spanish sovereignty. Tavera sadly confirmed that the Madrid government came to believe that the scheme was true without any attempt to investigate the real facts or extent of the alleged “revolution” reported by Izquierdo and the friars. Commented [ju3]: The manipulation of the Spaniards circled the country whereas they also manipulated the central Spanish government that the filipinos are against them. A form of corruption indeed. Convicted educated men who participated in the mutiny were sentenced life imprisonment while members of the native clergy headed by the GOMBURZA were tried and executed by garrote. This episode leads to the awakening of nationalism and eventually to the outbreak of Philippine Revolution of 1896. The French writer Edmund Plauchut’s account complimented Tavera’s account by confirming that the event happened due to discontentment of the arsenal workers and soldiers in Cavite fort. The Frenchman, however, dwelt more on the execution of the three martyr priests which he actually witnessed. Unraveling the Truth Considering the four accounts of the 1872 Mutiny, there were some basic facts that remained to be unvarying: First, there was dissatisfaction among the workers of the arsenal as well as the members of the native army after their privileges were drawn back by Gen. Izquierdo; Second, Gen. Izquierdo introduced rigid and strict policies that made the Filipinos move and turn away from Spanish government out of disgust; Third, the Central Government failed to conduct an investigation on what truly transpired but relied on reports of Izquierdo and the friars and the opinion of the public; Fourth, the happy days of the friars were already numbered in 1872 when the Central Government in Spain decided to deprive them of the power to intervene in government affairs as well as in the direction and management of schools prompting them to commit frantic moves to extend their stay and power; Fifth, the Filipino clergy members actively participated in the secularization movement in order to allow Filipino priests to take hold of the parishes in the country making them prey to the rage of the friars; Sixth, Filipinos during the time were active participants, and responded to what they deemed as injustices; and Lastly, the execution of GOMBURZA was a blunder on the part of the Spanish government, for the action severed the ill-feelings of the Filipinos and the event inspired Filipino patriots to call for reforms and eventually independence. There may be different versions of the event, but one thing is certain, the 1872 Cavite Mutiny paved way for a momentous 1898. The road to independence was rough and tough to toddle, many patriots named and unnamed shed their bloods to attain reforms and achieve independence. 12 June 1898 may be a glorious event for us, but we should not forget that before we came across to victory, our forefathers suffered enough. As we enjoy our freeedom, may we be more historically aware of our past to have a better future ahead of us. And just like what Elias said in Noli me Tangere, may we “not forget those who fell during the night.” http://nhcp.gov.ph/the-two-faces-of-the-1872-cavite-mutiny/ The incredible Father Burgos By: Ambeth R. Ocampo - @inquirerdotnet Philippine Daily Inquirer / 09:26 PM September 12, 2013 Fr. Dr. Jose A. Burgos (1837-1872) is a name always associated with Fathers Jacinto Zamora and Mariano Gomez. In 1872 the three priests, together with the snitch who testified falsely against them, were executed by garrote at the Luneta, in a spot close to the Rizal monument. Thus has the term “Gomburza” been burned into the minds of Filipino schoolchildren. Towards Awakening the National Spirit Jaime B. Veneracion A Fine Morning At about an hour ago today, February 17, exactly 8 a.m., 134 years ago, three priests were executed at a place not more than 250 meters from where we are. Just like today, it could have been a fine morning. There was no report of rain or storm in the newspapers. Yet the ambience at the open fields of what was then called Bagumbayan was nothing but stormy. A French writer-journalist by the name of Edmund Plauchut gave us an account of the execution, its prologue and all. “Late in the night of the 15th of February 1872, a Spanish court martial found three secular priests, Jose Burgos, Mariano Gomez and Jacinto Zamora, guilty of treason as the instigators of a mutiny in the Kabite navy-yard a month before, and sentenced them to death.” “The judgement of the court martial was read to the priests in Fort Santiago early in the next morning and they were told it would be executed the following day…Upon hearing the sentence, Burgos broke into sobs, Zamora lost his mind and never recovered it, and only Gomez listened impassively, an old man accustomed to the thought of death.” “When dawn broke on the 17th of February there were almost forty thousand of (Filipinos who came from as far as Bulakan, Pampanga, Kabite and Laguna) surrounding the four platforms where the three priests and the man whose testimony had convicted them, a former artilleryman called Saldua, would die. “ Saldua, who had claimed to handle Burgos correspondence with the mutineers, had hopes of a reprieve to the last moment. He was the first to be called and, even as he seated himself on the iron rest projecting from the post of the garrote and felt its iron ring round his neck, his eyes searched desperately for the royal messenger. The executioner quickly put an end to the informer’s hopes with the turn of the screw that broke his neck. “The three priests followed Saldua: Burgos ‘weeping like a child’, Zamora with vacant eyes, and Gomez head held high, blessing the Filipinos who knelt at his feet, heads bared and praying.” “He was next to die. When his confessor, a Recollect friar , exhorted him loudly to accept his fate, he replied: ‘Father, I know that not a leaf falls to the ground but by the will of God. Since He wills that I should die here, His holy will be done.’” Zamora went up the scaffold without a word and delivered his body to the executioner; his mind had already left it.” Burgos was the last, a refinement of cruelty that compelled him to watch the death of his companions. He seated himself on the iron rest and then sprang up crying: ’But what crime have I committed? Is it possible that I should die like this. My God, is there no justice on earth?’” “A dozen friars surrounded him and pressed him down again upon the seat of the garrote, pleading with him to die a Christian death. “He obeyed but, feeling his arms tied round the fatal post, protested once again: ‘But I am innocent!’” “’So was Jesus Christ,’ said one of the friars.””At this Burgos resigned himself. The executioner knelt at his feet and asked his forgiveness.” “’I forgive you, my son. Do your duty.’ And it was done. Leon Ma Guerrero (The First Filipino) from whose book can be read this account then continued where Plauchut left off: “We are told that the crowd, seeing the executioner fall to his knees, suddenly did the same, saying the prayers to the dying. Many Spaniards thought it was the beginning of an attack and fled panic-stricken to the Walled City.” If the Spaniards thought that by doing away with the three priests and the laypersons that supported them would solve the problem of restlessness in the populace, they were wrong. When a new generation of Filipinos gave importance to this event, its place in the annals of history was assured. By being connected to a bigger event (The Philippine Revolution of 1896), the Gomburza execution became historical. It was said that Francisco Mercado, father of Rizal, forbade his household to talk about Cavite and Gomburza. Yet it was possible that instead of modulating the impact of the event on the family, it merely fed more on young Jose Rizal’s curiosity – why this secrecy about the event? And the curiosity to know who these persons were could only be satisfied by the stories told discreetly by his older brother Paciano. On this matter, the evidence could be circumstantial -- Paciano at the time of the Cavite Mutiny was a student boarder at the residence of Fr. Jose Burgos. We have a sense of this when in recalling the event, Rizal had said: “Without 1872 there would not now be a Plaridel, a Jaena, a Sanciangco, nor would the brave and generous Filipino colonies exist in Europe. Without 1872 Rizal would now be a Jesuit and instead of writing the Noli Me Tangere, would have written the contrary. At the sight of those injustices and cruelties, though still a child, my imagination awoke, and I swore to dedicate myself to avenge one day so many victims. With this idea I have gone on studying, and this can be read in all my works and writings. God will grant me one day to fulfill my promise.” The critical phrase, as underscored in the above quotation, was “though still a child, my imagination awoke.” Rizal knew as a child of eleven what happened. His imagination was awakened... And aside from proposing to study (our past), he longed for the day to “fulfill my (his) promise.” What was this promise? Looking at subsequent statements, an ambivalent feeling he made on Jose Burgos, we can see this promise. Writing to Ponce seventeen years later, Rizal said: “‘If at his death Burgos had shown the courage of Gomez, the Filipinos of today would be other than they are. However, nobody knows how he will behave at that culminating moment, and perhaps, I myself, who preach and boast so much, may show more fear and less resolution than Burgos in that crisis. Life is so pleasant, and it is so repugnant to die on the scaffold, still young and with ideas in one’s head...’” Rizal judged the previous generations rather harshly: “The men who preceded us struggled for their own interests, and for this reason God did not sustain them. Novales for a question of ranks, Cuesta for vengeance, Burgos for his parishes. We on the other hand struggle that there may be more justice, for freedom, for the sacred rights of man; we do not ask anything for ourselves, we sacrifice Commented [ju4]: Seems like a conspiracy/ cover-up for something. Solidifies previous points all for the common good.” There were three elements in these statements important to Rizal. The first had something to do with bravery—the kind of calm acceptance of death as exhibited by the warriors, whom our peoples called the bagani or bayani. The other was the capacity to bear self-sacrifice, the kind exhibited by the Christian saints. In a way, these values harked to the days of our forefathers as further re-enforced by the heroes of the Christian faith. And then, sacrifice for what? Rizal’s vision of fighting for justice, for freedom and for the sacred rights of man, in other words, for doing not for oneself but for the whole, would transform an individual act into an act of sacrifice. As Fr. John Schumacher would say: “Hence in the mind of Rizal, the task was not so much to seek for reforms from the colonial regime as to build up a nation as a unified, self-reliant people, ready to take its place among the nations of the world in due time.” Yet even as Rizal condemned Burgos for his ambivalence in accepting the role of a martyr to a cause, at the moment when he wrote El Filibusterismo, it would appear that the execution had always been at the back of his mind. In his dedication of the book to Gomburza, Rizal had said: “As long then as your participation in the Cavite uprising is not clearly demonstrated, nor has it been shown whether you have been patriots or not, whether you have cherished longings for justice and for liberty, I have the right to dedicate to you my work as victims of the evil which I endeavour to fight. https://web.facebook.com/sampakabulacan/posts/506495399414762?_rdc=1&_rdr According to the La Solidaridad and French newsman Edmund Plauchut, it took place on February 16, 1872. Philippine history has it that the aftermath of the so-called Cavite mutiny was a mass purging of people who have been suspected of having led or supported it. On the day the news of the uprising reached the central government in Manila, the Governor-General immediately caused the arrest of prominent priests and civilians as conspirators of the mutiny, among them, the Gomburza. In an article written by Philippine historian Ambeth Ocampo, he said that during the trial, the principal witness was a certain Francisco Saldua who testified that the mutiny was a conspiracy, and confessed that he was a part of it. He wished to be pardoned in exchange for his testimony. He narrated on the trial that for three times he delivered messages to Fr. Jacinto Zamora, who had then gone to Burgos’ abode. Saldua said that the conspirators met at the home of certain Lorenzana. Some military witnesses testified that they were told that should the uprising succeed, the president of the republic would be Fr. Burgos, parish priest of the Manila Cathedral but all were just hearsay. A fellow priest, Fray Norvel, testified that the Creoles were inciting the people to rise up in arms against Spain, and that he saw Burgos passing subversive pamphlets. Lies and unfounded information subdued the trial. Fr. Burgos’ landlady testified as a sort of character witness. She vouched that Fr. Burgos was a peaceful man and with no liking for gossip. She said that Fr. Burgos would even advise the insurgents to seek reforms without spilling of blood or the recourse to violent means. He was the most distinguished among the three, having earned two doctorates one in theology and another in canon law. He was a prolific writer and was connected with the Manila Cathedral, a good swordsman and boxer. Burgos got into a quarrel more than once with his superior, Archbishop of Manila Gregorio Martinez, regarding the right of native secular clergy over those newly-arrived priests from Spain. After eight hours of trial, according to Ocampo, the Council of War condemned to die in the garrote the three priests Don Jose Burgos, Mariano Gomez, and Jacinto Zamora. Padre Burgos’ last words are as follows:"But I haven't committed any crime!" Reportedly one of the friars holding him down hissed,"Even Christ was innocent!" It was only then, it is said, when Padre Burgos freely accepted his death. There are present-day idiots like Francisco Saldua who, in order to save their neck, point at fellow human being with his far-fetched accusations. There are also the likes of Fray Norvel who has the bad feeling and implicate and accuse his brother priests. And there are still Archbishop Martinezes among us who favor friars (priests) from other places than the homegrown clergy. They are, too, the Padre Dámasos of our time… POSTED BY NORMAN NOVIO HTTP://NANOVIO.BLOGSPOT.COM/2015/02/PRIESTS-ON-TRIALGOMBURZA.HTML Famous Trials of the Philippines: The Gomburza Trial of 1872 Introduction Any discussion on famous trials of the Philippines can only begin with the trial of Fr. Mariano Gomez, Fr. Jose Burgos and Fr. Jacinto Zamora, (GOMBURZA). The case stemmed from the Cavite Mutiny, an event best described as an overnight disturbance, but which event led to the trial and execution of the three secular priests in the last few decades of the Spanish era in the Philippines. Historians marked the day of their execution as the day when the term “Filipino” became ingrained in the minds of the citizens of colonial Philippines leading to the advent of the Propaganda Movement in Spain, and eventually the Philippine Revolution of 1896. Rizal himself admitted that were it not for the three martyr priests, he would not been part of the Propaganda Movement and would have been a Jesuit priest instead. In spite of its significance, however, the proceedings of the trial have been kept hidden for many years. Fr. John Shumacher, a Jesuit historian, claims that until the present an objective history of the trial cannot be made until the trial records in Segovia, Spain are released to researchers. In 1896, at the start of the Philippine Revolution and twenty-four years after the trial and execution of the three martyr priests, members of the Katipunan extracted testimonies from captured friars who testified that the whole thing was a set- Commented [ju5]: In the line of rizal’s notes up. Considering, however, that the testimonies were extracted under duress, historians have argued on the credibility of the story. Commented [ju6]: Supporting comment tagged as: GOLD The Cavite Mutiny It is the late 19th century, and one of the key issues of the day is the secularization of parishes. Can the parishes be entrusted to the care of the local clergy? Fr. Burgos and Fr. Gomez championed the rights of the Filipino secular clergy to become the parish priests of local parishes over the claims of friars. Fr. Burgos was outspoken in his quest, and even wrote to newspapers in Spain for this cause. His insistence of secularization irritated the friars who belittled the abilities of the Filipino clergy to govern the parishes. Fr. Burgos's outspoken disposition on this issue even merited a warning from the Jesuit provincial, that should Fr. Burgos continue to speak and write about the secularization issue in public, Fr. Burgos may not turn to the Jesuits for help. The story begins with the arrival in Manila in 1871 of General Rafael Izquierdo y Gutierrez. On the day he assumed control of the colonial government, he declared that “ I shall govern with a cross and the sword in hand.” Whatever he meant by that, it seemed that the emphasis was on the sword. At that time, the Spanish government subjected the natives to forced labor and the payment of an annual tribute. The workers assigned to the navy yard and the artillery engineers and the arsenal of Cavite, however, were exempt from these obligations. These artisans were chosen from the infantrymen of the navy. They did not have any rank while they render service to the army. But General Izquierdo changed all that when he issued an edict removing these privileges, requiring them to pay tax and render forced labor, and removing from them the rights acquired from retirement. This edict is believed to have caused widespread dismay among those affected who staged the mutiny. Soon after the publication of the order, forty infantry solders of the navy and artillerymen led by a certain Sergeant Lamadrid seized the Fort of San Felipe in Cavite. Sergeant Lamadrid and his band of mutineers killed the officials who resisted. At ten o’clock in the evening when the rebels entered the fort, the rebels fired a cannon to announce victory to the city. But at dawn, the following morning, the rebels failed to get the support of the soldiers who remained loyal to their regiment. From atop the walls, the rebels called loyal soliders, induced them with promises to make them join the movement, but nothing proved successful. Instead, the regiment hurried to prepare an attack on the rebels, which caused the mutineers to hide in the fort, hoping that Manila would send the rebels help, but none came. Instead, a column composed of two regiments of infantrymen and one brigade of artillerymen with four cannons came from Manila to quell the rebellion. After a few preliminary assaults, which were not successful, the loyal forces decided to force the surrender of the mutineers by starving them, as it turned out that Fort San Felipe did not have any provisions. With the blockade in force, the mutineers realized their doom and Commented [ju7]: Made him the logical mastermind or identity of the mutiny for his cause or propaganda flew the white flag over the walls of the fort. In spite of the white flag being flung by the rebels, the loyal forces decided to divide into two groups to prepare for the assault of the fort. While this was being done, the principal gate of the fort was opened, and a small group of rebels carrying the flag of truce stepped out. The loyal forces allowed the rebels to take fifteen steps. When the rebels were near enough, the Spanish commander ordered his soldiers to fire. Nobody among the small group that stepped out survived. Thereafter, the loyal forces assaulted the fort, firing shots as they entered it. The rebels offered very little resistance, as the mutiny was completely suppressed. The aftermath of the mutiny was a mass purging of people who have been suspected of having led or supported it. On the day the news of the uprising was received in Manila, the Governor-General immediately caused the arrest of prominent priests and civilians as conspirators of the mutiny. Among them were Fr. Jose Burgos, Fr. Zamora, (curate and co-curate of the Manila Cathedral), Fr. Gomez (curate of Bacoor), D. Agustin Mendoza (curate of Sta. Cruz), Don Feliciano Gomez, Don Antonio Regidor (eminent lawyer and municipal councilor), Joaquin Pardo de Tavera (counsellor of the administration), Don Enrique Paraiso, D. Pio Basa (old employees), Don Jose Basan, Maximo Paterno, Crisanto Reyes, Ramon Maurente and many others. The Trial The sergeants and soldiers taken prisoners at the fort were court martialed and immediately shot, some in Manila and others in Cavite. Soldiers of the marine infantry had their sentences commuted to ten years of hard labor in Mindanao. Meanwhile, the clerics, lawyers, businessmen accused were tried by a special military court. Appointed fiscal of the government was a commandant of the infantry, a future governor of the province, Manuel Boscaza. The defenders were some officers of the infantry who were given only 24 hours to prepare their defenses. The rebels were charged with the crime of proclaiming the advent of a republic in agreement with the ideas of the leaders of the progressive parties of the Peninsula. During the trial, the principal witness was a certain Francisco Saldua, who testified that the mutiny was a conspiracy, and confessed that he was a part of if. He wished to be pardoned in exchange for his testimony. He testified that for three times he delivered messages to Fr. Jacinto Zamora, who had then gone to Burgos’s abode. Saldua said that Sergeant Lamadrid and one of the Basa Brothers told Saldua that the “government of Father Burgos” would bring the fleet of the United States to assist a revolution. He also testified that Ramon Maurente was financing it with 50,000 pesos, and Maurente would become the revolutions’ field marshal. Saldua also testified that the conspirators met at the home of Lorenzana. Some military witnesses testified that they were told that should the uprising succeed, the president of the republic would be the parish priest of St. Peter. At that time, Burgos Commented [ju8]: Red flag: It may have been that the people may have misunderstood burgos’ cause and saw his goal as the whole of overturning the gov’t. Thus, they have implanted a different idea regarding burgos’ actions. Commented [ju9]: It was not a direct order from Burgos was the parish priest of the Manila Cathedral, which was known as St. Peter as a parish. Fr. Jacinto Zamora was his co-curate. Other military witnesses mentioned the name of Fr. Burgos, or the native curate of St. Peter, as the one who would be president, but likewise this knowledge was only heard by them from someone. Enrique Genato testified that Fr. Burgos, Marcelo H. del Pilar, Regidor, Rafael Labra, Antonio Rojas and others spoke of clerics, wars, insurrections and rebellions at secret meetings. Marina Chua Kempo testified that she heard the conspirators speak of a general massacre of Spaniards and that Lamadrid, the leader of the mutiny, would be governor or captain general. Fray Norvel testified that the Creoles were inciting the people to rise up in arms against Spai, and that he saw Burgos passing subversive pamphlets. Fr. Burgos’s landlady testified as a sort of character witness. She vouched that Fr. Burgos was a peaceful man, devout to the virgin, and with no liking for gossip. She said that others might talk of guns and cannons and cry “Fuera oficiales, canallas, envidiosos, malvados! or Viva Fiipinas libre, independiente!”. But Fr. Burgos would advise them to seek reforms without spilling of blood or the recourse of violence. A curious piece of evidence was a note found in the belongings of Fr. Jacinto Zamora, a gambling and card game afficionado. The note said, “Big gathering. Come without fail. The comrades will come well provided with bullets and gunpowder.” (Nick Joaquin claims that this is a joke for bullets and gunpowder were idioms among card players to refer to gambling funds.) Captain Fontivel, Fr. Burgos’s counsel, moved to dismiss the case for lack of evidence. But the Governor General rejected it and ordered the court martial continued. The defense then moved that Saldua be called to the stand. But the court claimed that Saldua was too ill to be called to the witness stand. After eight hours of discussion, the Council of War condemned to die in the garrote the three priests Don Jose Burgos, Mariano Gomez, and Jacinto Zamora. Saldua was likewise sentenced to die. The others were either sentenced to ten years of hard labor or sent to the Marianas for a period ranging from two to eight years. At 11 o’clock in the evening of February 15, 1872, the Council of War dictated the sentence and asked the accused if they had anything to say in their defenses. Burgos and Zamora expressed their innocence, maintaining that they had no relation with the rebels of Cavite and that there had been no positive evidence against them. The curate Gomez, an old man of seventy years, (Nick Joaquin claims he was 85) said that he was sure his judges would consider him innocent, but seeing that he was denied confrontation with his accusers, a lawyer for his defense chosen by himself, would be useless, the trial over, in influencing those who already decided that he was guilty. The accused were led to the military jail and on the following day, the sentence was pronounced on them by the Commissary of the government himself. As part of the sentence, the Governor General ordered the Archbishop to defrock the priests as has Commented [ju10]: Connection of previous comment been the custom, but the archbishop refused to defrock the three martyrs until evidence of their guilt was presented to the archbishop. The evidence was never shown to the Archbishop. The Execution On February 16, 1872, a big crowd gathered to witness the execution. Saldua, with a smile on his lips for he thought that his pardon was forthcoming led the march. Saldua was followed by Burgos, who cried like a boy, bowing to friends as he recognized them from the crowd, and then Zamora -- who had gone mad and had a vague stare -followed. Last in line was Father Gomez who with eyes wide open, head held high, blessed the natives who were kneeling along the road. Saldua, expecting a pardon that never came, was the first to go to the scaffold. Then Fr. Gomez was called. Replying to his confessor, a Recollect, Fr. Gomez said, “Dear Father, I know very well that a leaf of a tree does not move without the Will of the Creator; inasmuch as He asks that I die in this place, may His will be done.” Minutes later, he was dead. Fr. Zamora rose when his name was called. He had gone mad two days before and he died without a final word. Fr. Burgos was the last to be called. Upon mounting the scaffold, he cried to Commissary Boscaza, “Gentlemen, I forgive you, and may God forgive you like I do.” Then he sat to his death chair. Suddenly, he stood up and cried, “But what crime have I committed? Is it possible that I should die this way? My God, is there no more justice on earth?” The friars went to him and obliged him to be seated again, begging him to die the Christian way. Fr. Burgos obeyed, and as he was being tied he rose exclaiming: “But I am innocent!” “Jesus Christ was also innocent,” exclaimed one of the friars. Then Fr. Burgos stopped resisting. Then the executioner knelt before the condemned man saying, “Father, forgive me if I have to kill you. I do not wish to do so.” Fr. Burgos repleid, “My son, I forgive you, comply with your duty.” Then the executioner did, and thereafter, Fr. Burgos was dead. The natives who gathered to witness the event knelt and recited the prayer of the dying. The Spaniards who saw the reaction of the natives panicked and ran to the city walls of Intramuros. The Aftermath After the execution, the Spanish colonial government prohibited people from talking about the execution, and the records of the trial were kept from the public. Jose Rizal soon published the novel, Noli Me Tangere", the plotline of which includes a creole character, Crisostomo Ibarra, who was set up by the friars that led to his being charged with sedition by the authorities. Nick Joaquin says this was Rizal's allusion to the fate of the three martyrs. On February 15, 1892, twenty years after the event, the La Solidaridad, the newspaper founded by the members of the Propaganda Movement, which included Jose Rizal, in Spain, published an account of the mutiny, trial, and the execution written by Edmund Plauchut, a Frenchman supposedly living in Manila at the time of the trial and execution, from whom most of the above narrative was derived. A few months earlier Jose Rizal dedicated his second novel El Filibusterismo to the three martyred priests. Appearing on the cover of the novel is a picture of the three martyred priests. Then in 1896, after achieving an early success as the Magdalo faction of the Revolution in Cavite, members of the Katipunan extracted a testimony from Fr. Agapito Echegoyen, a Recollect, who said that he learned from a fellow friar what really happened. He said that the heads of the friar orders had held a conference on how to get rid of Burgos and other leaders of the native clergy and had decided to implicate them in a seditious plot. A Franciscan friar disguised as a secular priest was sent with a lot of money to Cavite to foment mutiny, and negotiated with Saldua to denounce Burgos as the instigator of the uprising. Afterwards, the heads of the friar orders used a large bribe—“una fuerte suma de dinero” – to convince the Governor-General that Burgos should be arrested, tried, and condemned. Commented [ju11]: GOLD. The key to winning. :D Another friar, Fr. Antonio Piernavieja said that a certain Fray Claudio del Arceo disguised himself as Father Burgos, went to Cavite to spread the idea of an uprising. When the mutiny was suppressed, the friars exerted pressure on the Governor General through his secretary and a lady with great influence on him, plus a gift of 40,000 pesos. Commented [ju12]: Yesssssss Conclusion Fr. John N. Shumacher opines in his book, “The Making of A Nation: Essays on Nineteenth Century-Filipino Nationalism” published in 1991, that the testimonies of Fr. Agapito Echegoyen and Fr. Antonio Piernavieja on the alleged conspiracy against Fr. Burgos are not credible, because they were extracted while they were captives of the revolutionary army and made under duress. And perhaps, we can add that they were also hearsay. Thus, until we have a firsthand account of this alleged conspiracy, this question of whether the trial was a set up may not be put to rest. For if Burgos Gomez and Zamora were indeed innocent of any crime, what motive could we attribute to Commented [ju13]: Uh oh Governor General Izquierdo and his military trial court for having acted as such against the prominent priests? Or is it possible that the three martyr priests were just circumstantial victims of Spanish hysteria in the wake of the Cavite Mutiny? Historians note that the significance of the trial of the three martyr priests lies in the fact that it marked the day that nationalism was born in the minds of the Filipinos. By today’s standards, the trial of the three martyr priests could hardly pass the basic tenets of due process. Clearly, the evidence against the three priests is at best hearsay, circumstantial, and by no means establishing any guilt beyond reasonable doubt. Thus, it can be said that Filipino nationalism may have been borne out of the cry for justice for the three martyr priests, but justice could not be obtained from the Spanish colonizers. The foregoing accounts were taken from Edmund Plauchut’s article “The Philippine Islands” in La Solidaridad, February 15, 1892, and Nick Joaquin’s “How Filipino was Burgos?” in A Question of Heroes, published by the Filipinas Foundation in 1977 and reprinted recently by Anvil. Nick Joaquin based his trial accounts from Manuel Artigas who had copies of the trial records. Of course, Fr. Schumaker is saying that the authentic records are still in Segovia, Spain and prohibited from being disclosed to researchers. Finally, the date of execution has been officially marked on February 17, 1872 but according to the La Solidaridad and Edmund Plauchut, it took place on February 16, 1872. Posted by Marvin Aceron 2005 – 09 - 15 http://lavidalawyer.blogspot.com/2005/09/famous-trials-of-philippines-gomburza.html