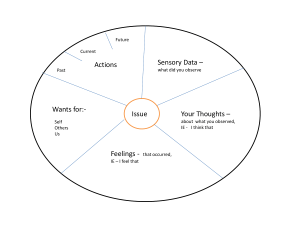

ACT Workshop Handout: Mindfulness & Acceptance Therapy

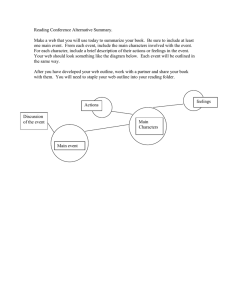

advertisement