Audit of Small Entities: Philippine Practice Statement

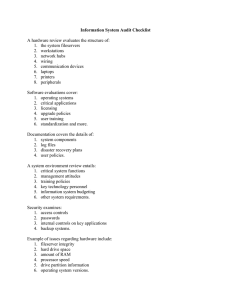

advertisement