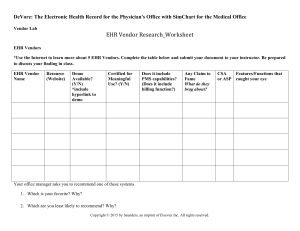

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: www.emeraldinsight.com/0952-6862.htm IJHCQA 31,2 Implementation of a nationwide electronic health record (EHR) The international experience in 13 countries 116 Leonidas L. Fragidis and Prodromos D. Chatzoglou School of Engineering, Democritus University of Thrace, Xanthi, Greece Received 13 September 2016 Revised 18 May 2017 Accepted 22 June 2017 Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to identify the best practices applied during the implementation process of a national electronic health record (EHR) system. Furthermore, the main goal is to explore the knowledge gained by experts from leading countries in the field of nationwide EHR system implementation, focusing on some of the main success factors and difficulties, or failures, of the various implementation approaches. Design/methodology/approach – To gather the necessary information, an international survey has been conducted with expert participants from 13 countries (Denmark, Austria, Sweden, Norway, the UK, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Canada, the USA, Israel, New Zealand and South Korea), who had been playing varying key roles during the implementation process. Taking into consideration that each system is unique, with each own (different) characteristics and many stakeholders, the methodological approach followed was not oriented to offer the basis for comparing the implementation process, but rather, to allow us better understand some of the pros and cons of each option. Findings – Taking into account the heterogeneity of each country’s financing mechanism and health system, the predominant EHR system implementation option is the middle-out approach. The main reasons which are responsible for adopting a specific implementation approach are usually political. Furthermore, it is revealed that the most significant success factor of a nationwide EHR system implementation process is the commitment and involvement of all stakeholders. On the other hand, the lack of support and the negative reaction to any change from the medical, nursing and administrative community is considered as the most critical failure factor. Originality/value – A strong point of the current research is the inclusion of experts from several countries (13) spanning in four continents, identifying some common barriers, success factors and best practices stemming from the experience obtained from these countries, with a sense of unification. An issue that should never be overlooked or underestimated is the alignment between the functionality of the new EHR system and users’ requirements. Keywords Critical success factors, Critical failure factors, EHR implementation, Implementation barriers, IT implementation approach Paper type Research paper International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance Vol. 31 No. 2, 2018 pp. 116-130 © Emerald Publishing Limited 0952-6862 DOI 10.1108/IJHCQA-09-2016-0136 1. Introduction Although previous studies have shown that the implementation process is as important as the system itself, the implementation of nationwide electronic health record (NEHR) system has progressed much more slowly worldwide than it was initially anticipated (Morrison et al., 2011). There are a number of reasons, such as the continuously changing system characteristics and the politically driven contractual relationships among healthcare providers, which seems to prevent the successful completion of electronic health record (EHR) system’s development (Sheikh et al., 2011). The majority of stakeholders are aware of the magnitude of the problems arising from the implementation of such a system and they understand that it is unrealistic to hold high expectations concerning the operational functions of these systems. The scope of this research is to point out the best practices, in respect to organizational and operational issues, adopted during the implementation process of the NEHR system already in operation worldwide. The main goal is to explore the knowledge gained by experts in the field of NEHR system implementation. The NEHR system is defined as a Conflicts of interest: the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in the research. national information system which ensures interoperability between EHR systems obtained/developed from different vendors, either in the public or private sector, which meets specific national interoperable standards (Morrison et al., 2011). It is clarified that this research attempts to present some of the common characteristics/problems of the implementation of the NEHR system in a unified way ( framework) in order for the readers to be able to understand the global development as far as this issue is concerned. Subsequently, a further discussion regarding some of these issues is carried out. In the current research, an international survey was conducted and experts (stakeholders) with significant roles, from 13 countries, have accepted to participate and share their experience with the research community. Four participants where the project managers of the NEHR system implementation, three where the directors of the corresponding national organization (or of the appropriate department) for NEHR implementation, while three more participants have had the role of the principal advisor of the respective organization in their countries, which is in charge for eHealth national infrastructure, strategy, policy and standards. Furthermore, two more participates where the chief officers (chief information officer or chief technology officer (CTO)) concerning eHealth development strategies, standards for interoperability, business and technical architecture guidelines. Moreover, one participant was the chairman of a national independent not-for-profit organization, promoting EHR systems. Finally, eight participants come from Europe (Denmark, Austria, Sweden, Norway, the UK, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland) and five from the rest of the world (Canada, the USA, Israel, New Zealand and South Korea). It should be made clear that the purpose of the survey was neither to compare the NEHR implementation adopted from different countries, nor to develop a guide to successful NEHR implementation. This is because the priorities that each country poses for EHR implementation differ, something that naturally leads to the development and implementation of a very diverse EHR system in each country. The current research highlights the best practices and the different approaches adopted by the leading in the field of NEHR implementation countries, taking into account the specific characteristics of each country. This research, therefore, attempts to identify some of the critical success and failure factors (difficulties – barriers) along with the best practices of the implementation process of NEHR that could be used as a reference point for other countries that intend to follow. 2. Literature review In Europe, 19 out of 33 countries are still at the planning stage of the development and implementation process of a patient summary and EHR-like system (Stroetmann et al., 2011). The leading in the field countries in Europe are Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, the UK, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland. Worldwide, Canada and Australia are the countries with the most advanced stage of NEHR implementation (Thomson et al., 2013). Denmark is considered as a leading country as far as eHealth integration and healthcare delivery services are concerned (Kierkegaard, 2013). Similarly, in Sweden, efforts toward investigating relevant systems, both at the county and national level, are in progress aimed at enhancing their compatibility in order to increase security and effectiveness ( Jerlvall and Pehrsson, 2012). Furthermore, in Norway, a governmental organization, called the National Health Network, is in charge for the establishment of a single information exchange platform for health providers and authorities. In England, the current approach introduces the Summary Care Records, which will store a limited range of data (current medication, adverse reactions and allergies) for all patients except those who choose not to have one (Cresswell et al., 2012). In Austria, EHR was initiated in 2005 with the health reformation law (Austrian Health Care Reform Act, 2005). Like in other countries, the development of an EHR system in Austria is facing A nationwide EHR 117 IJHCQA 31,2 118 significant challenges, like standards definition and structure of the content, along with terminology harmonization. The overall progress of the EHR project in Germany (E-Health Act, 2015) has been delayed several times, due to the technical complexity and strong resistance of health professional organizations (Hoerbsta et al., 2010). Furthermore, in the Netherlands, the idea for an EHR system was initially discussed in October 1996 (Barjis, 2010). Dutch authorities have already establish, a central health information technology (HIT) network, called AORTA, in order to facilitate information exchange across healthcare providers. Moreover, Switzerland’s health system is recognized as a high quality and high cost one (OECD/WHO, 2011). However, the interoperability of all EHR systems has not been achieved yet, since the integration of hospitals’ EHRs varies significantly among cantons. In Canada, there is not a national strategy for implementing an NEHR system and there is no national patient identifier (Mossialos et al., 2016). However, efforts for the adoption of interoperable EHR are increasing rapidly and, according to Infoway’s Corporate Plan 2016-2017, efforts for establishing pan-Canadian common standards and interoperability will be continued. On the other hand, the USA decided in 2003 that its residents should have an EHR system in ten years, adopting the bottom-up implementation approach. Later, on February 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (2009) was introduced, where the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act was enacted, in order to promote and expand the adoption of HIT. In Australia, a new commission for eHealth is in charge from July 2016, and the person controlled EHR system was online in July 2012. Furthermore, in September 2010, New Zealand launched the National Health IT Plan. The main challenge is the difficulty of the implementation of a national patient portal taking into account the current low level of interoperability among EHR systems and, also, considering that there are legacy systems which are still operable (Monsen et al., 2010). Israel is the first country in the world that introduced (in mid 1990s) health IT information exchange systems, with virtually 100 percent of its primary-care doctors using EHR (Peterburg, 2010). There is not a central point where the data are kept but all information remains in its original format, location, system and ownership. Finally in Korea, a health information exchange project was initiated by the government, in 2014, with the aim of establishing a healthcare ICT infrastructure, which will be able to support systems integration and share and utilize health information, using both wired and wireless networking. 2.1 Similar studies A very useful research concerning the adoption of electronic medical records in primary care and the lessons learned from health information system (HIS) implementation experience in seven countries (Canada, the USA, Denmark, Sweden, Australia, New Zealand and the UK) was conducted by Ludwick and Doucette (2009). These researchers suggests that the quality of the implementation process is as important as the quality of the system being implemented. They also stresses that, in order EHR implementation process to be successful, factors such as health system usability, computer skills and system’s fit within the organizational culture should be carefully considered. Additionally, the same study has shown that the outcome of the implementation process is affected by the quality of the design of the systems graphical user interface, the functionality of the features incorporated, project management, procurement and users’ previous experience. Another relevant study concerning the problems of EHR systems in five countries (England, Germany, Canada, Denmark and Australia) has been conducted by Deutsch et al. (2010). They found that strategic, organizational and human challenges are usually more difficult to master than technical aspects. The critical areas were used in the current research in setting up a number of structured questions, concerning the main difficulties faced during the implementation process (as illustrated in Table II). Furthermore, Stroetmann et al. (2006) studied ten European eHealth projects, and determined six key factors for the successful development and implementation of health systems. These six key factors were also used in the current study in order to identify the critical success factors as far as the implementation of an EHR system is concerned (as presented in Table IV ). Lluch (2011) reviewed the relevant literature in order to identify the barriers to the use of HIT in the health sector. The main finding of this study is that some of the barriers preventing a successful HIT implementation can be approached from an organizational management perspective. Similarly, McGinn et al. (2011) conducted a systematic literature review, aiming to provide a synthesis of the knowledge about the barriers and facilitators influencing shared EHR implementation among its various users. It was revealed that the most frequent adoption factors, common to all user groups, were: design and technical concerns, ease of use, interoperability, privacy and security, costs, productivity, familiarity and ability with EHR, motivation to use EHR, patient and health professional interaction and lack of time and workload. The main conclusion was that, despite the fact that important similarities exist between user groups, there are also significant differences, thus, suggesting that each user group has a unique perspective on the implementation process that should be taken into account. Another study (Morrison et al., 2011), concerning the approaches used for an NEHR system implementation, has shown how different healthcare systems, national policy contexts and anticipated benefits have shaped the initial strategies. Coiera’s (2009) typology of national programs (“top-down,” “bottom-up” and “middle-out”) was used in order to review EHR system implementation strategies in three representative countries: England, the USA and Australia. In England, a government-driven centralized national approach was applied and this approach is considered as a “top-down” approach. In contrast to the English approach, the USA decided to either transform local healthcare organizations’ operational systems or develop new local healthcare information systems, which represents the “bottom-up” approach. Australia, on the other hand, followed a “middle-out” approach, where the government finances and supports national infrastructure, standards development and tools (combined with local choice for compatible, clinical IT systems). With middle-out approach, the local healthcare providers, along with their IT vendors, progressively change their information systems with the aim to comply with national information systems standards, in order to achieve higher interoperability standards with the evolving national health information network. Interoperable EHR systems are considered as an important tool with the potential to control healthcare cost (Kaushal et al., 2015). 3. Research methodology The primary aim of this research was to capture the existing experience from countries where nationwide EHR systems have already been implemented or they are in a medium to mature implementation phase. For that reason, experts with experience in implementing NEHR in many different countries were invited to participate in this survey and share their knowledge and experience with the academic community and other practitioners. 3.1 Survey design Initially, the appropriate questions were identified from the available relevant scientific literature and experts in the field of HIS implementation. More specifically, a number of lengthy discussions took place with medical, nursing, technical and administrative staff. A nationwide EHR 119 IJHCQA 31,2 120 Particular attention was given to the interviews that were conducted with expert staff of the IT departments of hospitals (developers, analysts and head of department), in order to clarify the most appropriate questions. Useful discussions and information exchange with researchers in the field of HIS, eHealth and EHR took place, in three relevant international scientific conferences, more specifically during the 11th IEEE International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (Pafos, Cyprus), HEALTHINF 2013 (Barcelona) and the 10th International Conference on Information Communication Technologies in Health (Samos, Greece). During the last conference, an invitation was from the chairman of a national independent not-for-profit organization supporting high-quality HER, to join the LinkedIn Professional Network group of the European Federation for Medical Informatics – Health Information Management in Europe (EFMI-HIME). After joining this specific group, we opened a discussion in EFMI-HIME group titled “Technical and Operational information of EHR System and Implementation difficulties (approaches).” The response of eight members who are specializing in the field of eHealth participated in the discussion. From this opinion exchange process, some very useful suggestions, concerning the structure of the survey and the consideration of new sources concerning EHR implementation, were obtained. After a careful consideration of the propositions expressed by the experts, it was decided to present some of the initial findings concerning EHR implementation in a third conference in order to receive new feedback ( from more researchers). A paper-based survey was conducted during the 3rd HEALTHINF 2013 (International Conference on Health Informatics, Barcelona, Spain) and the proposed international survey was validated and modified based on the comments of more researchers in the field. 3.2 Survey instrument Utilizing the experience gained from studying the literature and the discussions with experts and researchers, a complete structured questionnaire was constructed. The questionnaire consists of four sections (General questions, EHR implementation, Documents submission and Additional info). Once the data collection instrument was completed, it was evaluated by three e-HIS vendors before it was sent out to the appropriate participants worldwide. A preliminary list of experts in the field of EHR systems implementation from European organizations was generated and an evaluation request was sent to them. The valuable feedback received, from a president of a European independent not-for-profit organization promoting the use of high-quality EHR and from a treasurer of an association concerning EHR standards helped us to modify the survey instrument in many sections (more options were included in some structured questions) in order to improve the clarity of the answers and, thus, their usefulness. 3.3 Participants identification Initially, the website of the European Patient Smart Open Services (2014), which is a European eHealth project that supports interoperability between EHR systems in Europe, was used, since it offers a list of all project beneficiaries, including organization names and contact details, of the representative person for each European country. An e-mail was sent to all the representatives where a description of this research was included and a participation in the survey request was addressed. In a few cases where no response was received, a thorough search in each country’s organization website, which is responsible for EHR implementation, was performed, in order for another person’s contact details to be detected. The same method was followed for the non-European countries, in order for specific contact details of the appropriate people to be obtained. These countries are: Denmark (DK), Austria (AU), Sweden (SE), Norway (NO), the United Kingdom (UK), Germany (DE), the Netherlands (NL), Switzerland (CH), Canada (CA), the United States of America (USA), Israel (IL), New Zealand (NZ) and South Korea (KO). The participants of the survey belong to different stakeholder group, such as ministries of health, national centers of eHealth (coordinating and promoting nationwide use of IT), not-for-profit governmental organizations (in charge for EHR implementation), Commonwealth Health Corporations and independent not-for-profit organizations (EHR system certification development). There were no excluding criteria for the participation of a country, but in contrast, an attempt was made to find people from all the countries that have implemented (or are in the process of implementing) NEHR systems. A nationwide EHR 121 4. Results In this section, part of the answers provided by each one of the 13 experts in each question is presented. Since all the questions in the survey were optional, there are some boxes in some tables which are blank indicating that no answer was provided. It should also be stressed that, apart from choosing the answers for each question, the survey participants were also asked to rate the importance of each given option, where it was applicable. 4.1 Healthcare systems Three different types of healthcare systems exists worldwide (Fried and Gaydos, 2002). These are the publicly funded systems (implying that a universal healthcare system exists which is funded through taxation), the private-funded systems (personal contribution meets the non-taxpayer refunded portion of healthcare) and the totally private systems (where healthcare is either paid out of pocket or met by some form of personal- or employer-funded insurance). Looking at the results (Table I), it can be easily noticed that in Europe (all European countries except Switzerland – CH) the development and implementation of EHR is totally publicly funded (except Germany – DE, where although 90 percent of the statutory healthcare is publicly funded, there is also a small portion of 10 percent which is totally private). On the other hand, from the non-European countries only Canada and South Korea have publicly funded EHR Systems. Although in the USA, most people used to pay for their insurance by themselves, with Medicare (national social insurance program), National healthcare systems Publicly funded Private funded Totally private DK UΚ CA | | | EHR implementation approach – method used Top-down | Bottom-up Middle-out | # | US IL NZ | * | | KO CH | | # DE SE NO AU NL * | | | | | | | | | | | | | # | Reasons of the chosen EHR implementation approach – method Political reasons (3) (5) (4) (5) (5) (3) | (4) (5) Current HIS (4) (4) (5) | | (4) Feasibility of implementation (5) (4) | (4) Cost (3) (3) (3) Notes: Countries having adopted the middle-out, bottom-up and top-down approach. Tick symbol (|) denotes participant’s selection. Blank space indicates that no answer was provided. Asterisk symbol (*) indicates the initial approach used. Hash symbol (#) indicates future direction. Numbers indicate the level of importance of each reason (1 ¼ slightly important, 2 ¼ fairly important, 3 ¼ important, 4 ¼ quite important, 5 ¼ very important) Table I. National healthcare systems – EHR implementation approach IJHCQA 31,2 122 health insurance is funded for citizens aged 65 and older, who have worked and paid into the system through the payroll tax, while with Medicaid (social healthcare program), people with low income, along with special cases (elderly, disabled, children, veterans), insurance is covered by the government. 4.2 EHR implementation approach Different EHR implementation approaches have been adopted from the participating countries (Table I) in order for the EHR system to be operable. More specifically, three countries have chosen the “top-down” approach, which is a government-driven centralized national approach, four countries have chosen the “bottom-up” approach, where each local healthcare organization transforms operational systems or develops new healthcare information systems, while five countries have adopted the “middle-out” approach, where the local healthcare providers progressively change their information systems in order to comply with national information systems standards. It is worth mentioning that although the top-down approach was used in the UK, it was abandoned in 2010, replaced by a more locally middle-out approach ( followed by individual NHS Trusts), while in the USA, although the bottom-up approach was initially adopted, nowadays it is moving toward a middle-out approach (Morrison et al., 2011). Moreover, in Germany, integrated personal health system efforts are currently not driven by the state and since there is no central infrastructure to support them, the numerous small local initiatives constitute a bottom-up approach (Bratan et al., 2013). However, what is more important is to examine the reasons why each country has chosen the specific EHR implementation approach. As can be seen in Table I, political reasons are the predominant reason, for 9 out of the 13 countries, for choosing the specific implementation approach. 4.3 Main difficulties during the EHR implementation process Next, in line with the results of the work of Deutsch et al. (2010), it was found that the major difficulty in the EHR implementation process is users’ acceptance of the new system (Table II). Users’ acceptance is not only the most frequent choice but, also, the most highly rated one. On the other hand, although Deutsch et al. suggest that “funding” is an equally critical issue to “acceptance,” the results of the current study do not confirm this perception. More specifically, “EHR project funding” is not so highly ranked and it is reported as the fifth most important difficulty (Table II) (in line also with the results presented in Table I). Another difference among the two research studies is that “interoperability standards” is displayed in third place in Table II, while in the research of Deutsch et al., it is the least DK UΚ CH CA US IL NZ KO DE SE NO AU NL Table II. Main difficulties during the EHR implementation process Users’ acceptance (4) (4) (5) (5) (3) (5) (5) (5) Project management (4) (4) (5) (5) (3) (4) Interoperability standards (4) (4) (3) (5) (4) (4) Data protection and safety (5) (5) (4) (4) EHR project funding (4) (4) (3) | Technical architecture – network connection (4) Health policies (3) Notes: Countries having adopted the middle-out, bottom-up and top-down approach. Tick symbol (|) denotes participant’s selection. Blank space indicates that no answer was provided. Numbers indicate the level of importance of each reason (1 ¼ slightly important, 2 ¼ fairly important, 3 ¼ important, 4 ¼ quite important, 5 ¼ very important) important. “Project management” was ranked second most important and most frequently reported factor in Table II but in Deutsch et al., research is ranked third. Turning the attention to ways of overcoming these difficulties (Table III), “apply modifications to current EHR software,” “information campaigns tailored to users’ needs” and “governmental act” are proposed as the most significant options. A nationwide EHR 4.4 Critical success factors for EHR system implementation In the same line, “commitment and involvement of all stakeholders” is considered from all participants as the most critical success factor for the implementation of an NEHR system (Table IV ). “Clear long-term perspectives, endurance, and patience” is considered as the next critical factor from ten participants. Similarly, ten participants suggest that good organizational change management, interdisciplinary teams with IT experience and clear incentives are important success factors of EHR system implementation. Commitment and involvement of medical staff is also considered as a very important success factor, since six out of the eight experts who have select this factor have rated it with five, in the 1-5 rating scale. The key factors displayed in Table IV were based on eHealth IMPACT study, which demonstrates the potential of eHealth as an enabling tool for meeting the “grand challenges” of European health delivery systems, and was financed by the European Commission, Directorate General Information Society and Media, ICT for Health Unit (Stroetmann et al., 2006). 123 DK UΚ CH CA US IL NZ KO DE SE NO AU NL Apply modifications to current EHR software (5) (4) (4) (5) (4) (5) (5) | Information campaigns tailored to users’ needs (5) (3) (3) (4) (5) (4) Governmental act (1) (5) (5) (5) Change project management (5) (3) Replace current EHR software | Notes: Countries having adopted the middle-out, bottom-up and top-down approach. Tick symbol (|) denotes participant’s selection. Blank space indicates that no answer was provided. Numbers indicate the level of importance of each reason (1 ¼ slightly important, 2 ¼ fairly important, 3 ¼ important, 4 ¼ quite important, 5 ¼ very important) Table III. Ways of overcoming EHR implementation difficulties DK UΚ CH CA US IL NZ KO DE SE NO AU NL C&I of all stakeholders (4) (5) (5) (5) (5) (5) (4) (5) (5) (4) (4) (4) (5) Clear long-term perspectives, endurance and patience (5) (3) (5) (5) (4) (4) (5) (4) (4) (4) Good organizational change management, interdisciplinary teams with IT experience and clear incentives (5) (4) (4) (5) (4) (5) (3) (4) (4) (4) C&I of medical staff (5) (5) (4) (5) (5) (4) (5) (5) A strong health policy and clinical management (4) (5) (4) (5) (3) (4) Regular analysis of costs, incentive systems and benefits organizational changes in the clinical sector (4) (4) (4) (4) (5) C&I of administrative staff (5) (4) (5) (5) C&I of nursing staff (5) (4) (5) (5) Notes: C&I, commitment and involvement. Countries having adopted the middle-out, bottom-up and top-down approach. Blank space indicates that no answer was provided. Numbers indicate the level of importance of each reason (1 ¼ slightly important, 2 ¼ fairly important, 3 ¼ important, 4 ¼ quite important, 5 ¼ very important) Table IV. Critical success factors for EHR system implementation IJHCQA 31,2 124 4.5 Critical failures (barriers) during EHR system implementation On the other hand, the most critical failure factor in the implementation process of an NEHR system is the lack of support and the negative reaction to any change from the medical, nursing and administrative community (Table V ). In contrast to common beliefs, low budget or poor resources are not considered as very important factors for EHR system implementation failure. The critical failures (barriers) listed in Table V are based on the survey conducted by the Medical Records Institute, where the principal barriers of EHR implementation were determined (as cited by Deutsch et al., 2010). 4.6 Practices to be repeated in a future EHR implementation process In an attempt to examine what was done properly (best practices), participants were asked to select or name practices they would repeat in a future NEHR implementation process. The result (Table VI) shows that although “the commitment at the highest level and the coordination of IT/business strategies” has attracted a slightly lower rating (34) than the next two practices, it is considered as the best practice since six out of seven participants (who have select this practice) have rated it with 5 (very important), in the 1-5 rating scale. Both “high usability and interoperability or integration based on standards taking basic legal requirements into account” (three out of eight have rated it with 5) and “aligning functionality with user requirements and work processes” ( four out of eight have rated it with 5) were recommended from eight experts in total and have collected the same rating (35). Other less (but still) important practices are: “understanding of the culture of the health sector, as well as the use of an evolutionary approach” and “project management.” These practices that were proposed to the experts (listed in Table VI) were based on the Brender et al. (2006) study concerning the factors that influenced the success and failure of health informatics systems. 5. Discussion The adoption of the appropriate NEHR implementation approach plays a crucial role as far as system development time and budget for each country is concerned. DK UΚ CH CA US IL NZ KO DE SE NO AU NL Table V. Critical failures (barriers) during EHR system implementation Too little support and negative reaction to any change from the medical, nursing and administration staff (5) (4) (3) (5) (5) (3) (5) (5) No clear goals and lack of functionalities really needed (5) (5) (5) (5) Quality of EHR systems available (2) (4) (4) (4) (4) (2) Total underestimation of the level of complexity (5) (4) (4) (4) Emergence of fragmented solutions (4) (4) (4) Creation of a strong business case (ROI) (2) (5) (4) Finding an EHR solution that fulfills one’s own requirement (5) (5) Migration from paper-based to electronic files (4) (5) High costs of EHR system (3) (4) Difficulty to evaluate appropriate EHR solutions or components (4) Low budget/poor resources (4) Notes: Countries having adopted the middle-out, bottom-up and top-down approach. Blank space indicates that no answer was provided. Numbers indicate the level of importance of each reason (1 ¼ slightly important, 2 ¼ fairly important, 3 ¼ important, 4 ¼ quite important, 5 ¼ very important) DK UΚ CH CA US IL NZ KO DE SE NO AU NL Commitment at the highest level and coordination of IT/business strategies (5) (5) (5) (5) (5) (4) (5) High usability and interoperability or integration based on standards taking basic legal requirements into account (4) (5) (4) (5) (4) (4) (4) (5) Aligning functionality with user requirements and work processes (4) (4) (4) (3) (5) (5) (5) (5) Understanding the culture of the health sector and an evolutionary approach (4) (5) (5) (5) (5) (5) (4) Project management (4) (4) (5) (5) (5) (5) (4) Willingness to change, intensive communication, training of and cooperation between IT and other persons involved (5) (4) (5) (5) (4) Adequate cost-effectiveness, benefits and funding (4) (5) (5) (3) (5) Notes: Countries having adopted the middle-out, bottom-up and top-down approach. Blank space indicates that no answer was provided. Numbers indicate the level of importance of each reason (1 ¼ slightly important, 2 ¼ fairly important, 3 ¼ important, 4 ¼ quite important, 5 ¼ very important) 5.1 EHR implementation approach and healthcare systems funding The results show that the “middle-out” approach is the predominant approach adopted by almost all the non-European countries. On the other hand, three of the European countries have adopted the top-down, while three more the bottom-up approach. It is not clear whether this is related to the funding body (as it is shown in Table I) or not, but it is obvious that the countries where EHR implementation is funded by the state have adopted either the top-down or the bottom-up approach. Furthermore, the selection of the implementation approach is probably influenced by each country’s administrative structure. For example, in Norway and Sweden, where the healthcare system is considered decentralized, while county councils are responsible for the organization and provision of healthcare services (Thomson et al., 2013), the bottom-up approach is followed. Similarly, Switzerland, which consists of 26 cantons that are responsible for licensing providers vendors, hospital planning and the subsidizing of institutions and organizations (Thomson et al., 2013), has also chosen to adopt the bottom-up implementation approach. However, regardless of the NEHR implementation approach followed, the establishment of a unique patient identifier on a national level is an important priority, where 9 out of 13 countries already using it (as illustrated in Table VII). 5.2 Issues and considerations during the EHR implementation process A business architecture director has stated that “the political imperative came from frustration and lack of local activity.” Moreover, it was also proposed by a CTO that “overall strategy and definition of the EHR” is another quite important reason. Furthermore, the same expert insists that special consideration should be given to current and legacy systems. A project leader and senior clinical informatics specialist stated that it is easy to underestimate the complexity of healthcare and how the system needs to respond. Apart from the difficulties in implementing EHR systems, more issues emerged from the comments made by a CTO. These issues are the EHR adoption and use by clinicians, the EHR implementation cost, the EHR system productivity and, also, the training for using an EHR system. Furthermore, as the CTO underlines, all projects are taking longer than expected to be developed and implemented, while sometimes analysis-paralysis phenomenon arises. It was also suggested that a more step-by-step approach in the release of the new system should be followed. A nationwide EHR 125 Table VI. Practices to be repeated in the future EHR implementation process IJHCQA 31,2 126 Table VII. Unique personal identifier usage Country Personal identifier Denmark Yes Comments A unique electronic personal identifier exists for every Danish citizen, which is used in all health databases The UK Yes The NHS number assigned to every registered in the UK is considered as a unique personal identifier Switzerland Yes Each Swiss resident holds a personal identification number Canada No There is no national patient identifier The USA No Absence of a universal patient identifier Australia Yes Each person has a unique personal identifier New Zealand Yes Every person using health services has a national health index number which is used as a unique identifier Israel Yes Each citizen has a unique patient identification number Korea No There is no unique patient identifier that can be used only for medical purposes Germany No Absence of a unique patient identifier Sweden Yes Every Swedish has a personal electronic identity number Norway Yes All residents in Norway are assigned a unique personal identification number Austria Yes Patient’s social insurance number is considered as the unique patient identifier The Netherlands Yes All Dutch patients have a unique identification number Note: Countries having adopted the middle-out, bottom-up and top-down approach 5.3 Ways of overcoming EHR implementation difficulties Information campaigns, as a way of overcoming EHR implementation difficulties, should also be directed at doctors and not only to patients, because they also need persuasion in order to accept a new EHR system, as was noted by a business architecture director. It should also be stressed that a project manager has recommended two more ways of overcoming EHR implementation difficulties (“the inclusion of different actors” and “the integration of stakeholders” – both rated as “very important”). Finally, another participant, the director of a national organization for EHR implementation, suggested that most difficult situations will be resolved over time with the adoption of good project management practices and processes reengineering. 5.4 Success factors for EHR system implementation More success factors that were considered important and were proposed by the experts are: industry support (proposed by a project manager), benefit for professionals (proposed by a chairman) and the solution must provide early benefits for many stakeholders (not only to the fund provider) (proposed by a director of a national organization for EHR implementation). Another project manager commented that the administrative staff will be the key in the successful implementation process, since they will be required to equally support all the users of the new system. Another condition for success is to ensure continuous engagement and a productive dialogue between clinical and administrative users on the one hand, and ICT experts on the other, taking into account that the only people who can help identify the requirements and modifications needed to an ICT system are the users, themselves (Brender et al., 2006). Another aspect that was raised by a CTO was that a more evolutionary approach in funding should be followed, and that IS funding should be guaranteed for every province. Furthermore, it is necessary for healthcare administrators to evaluate EHR benefits and disadvantages to strengthen efficiency, lower costs and improve patient care (Tsai et al., 2014). 5.5 Barriers during EHR system implementation A CTO mentioned the fact that the community office physicians are not familiar or trained to interoperate with an EHR. Clinicians, as IT users, are not well prepared to express their requirements, with respect to EHR functionality and interoperability. This occurs because healthcare professionals, who are essential users of eHealth systems, are too often not sufficiently involved in the implementation process (Lluch, 2011). Furthermore, a project manager argues that fragmented systems do speed up departments’ processes, but may cost more in the production phase. Finally, a business architecture director underlines that technical and functional issues can be sorted out, but without the confidence and support of users, the system will never be used. Moreover, another project manager also highlighted that it is not always preferable to align IT systems with current work processes but, sometimes, work processes need to be aligned with IT systems. Otherwise, the full value of the IT systems used cannot be captured. A nationwide EHR 127 5.6 Strengths of the research Introducing a nationwide EHR system requires a huge amount of change for different stakeholders. These changes depend, to a large extend, on the implementation approach that each country decide to adopt. Taking into account the heterogeneity of each country’s financing mechanism, health system and health IT infrastructure, along with the characteristics of the participated countries, this research offers an overview of what/why/ how has been achieved by other countries and offers some general guidelines to the countries that intend to implement new NEHR, proposing useful suggestions concerning the proper and more relevant implementation approach. Another strong point of the current research is the inclusion of experts from a number of countries (13) spanning in four continents. Furthermore, bearing in mind that EHR development is very diverse in each country, this research identifies some common barriers, success factors and best practices stemming from the experience obtained from many countries, with a sense of unification and not of comparison (Table VIII). Countries Difficulties – barriers of EHR implementation process Users’ acceptance Project management Interoperability standards Success factors for EHR system implementation Commitment and involvement of all stakeholders Clear long-term perspectives, endurance and patience Good organizational change management, interdisciplinary teams with IT experience and clear incentives Commitment and involvement of medical staff Best practices in EHR implementation process Aligning functionality with user requirements and work processes High usability and interoperability or integration based on standards taking basic legal requirements into account Commitment at the highest level and coordination of IT/business strategies Understanding the culture of the health sector and an evolutionary approach Good project management 8 6 6 13 10 9 8 8 8 7 7 7 Table VIII. Common results to most countries IJHCQA 31,2 128 5.7 Limitations of the research Although the current research has been conducted to four continents (Europe, North-America, Oceania and Asia) with the participation of more than 13 countries, the results could not be generalized, since the characteristics of the health system, as well as the strategic target, significantly differ from country to country. Furthermore, despite the fact that the participants of this survey belong to different stakeholder group, it would be necessary to add some more experts (with various roles in the NEHR implementation process) in order to enhance the representativeness of the sample and the validity of the findings. Finally, additional structured interviews should be carried out in order verify the research findings. 6. Conclusions In the current research, experts from 13 countries (eight from Europe and five from the rest of the world) have provided some useful insight, as far as the NEHR implementation process is concerned. Considering the limitations of this research, especially the heterogeneity amongst the participated country’s healthcare systems and the limited representation of the stakeholders, this research can be used as a reference point for other countries that intend to proceed in NEHR system implementation for issues concerning: the EHR implementation approach to follow, the main difficulties and how to overcome them during the implementation process and the critical success factors and critical failures – barriers. References American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (2009), “United States of America”, available at: www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ5/PLAW-111publ5.pdf (accessed April 10, 2016). Austrian Health Care Reform Act (2005), “Austrian Government”, BGBl. I Nr. 179/2004. Barjis, J. (2010), “Dutch electronic medical record – complexity perspective”, 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Honolulu, HI, pp. 1-10, doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2010.162. Bratan, T., Engelhard, K. and Ruiz, V. (2013), Strategic Intelligence Monitor on Personal Health Systems, Phase 2: Country Study: Germany, RC Scientific and Policy Reports – European Commission, Seville, available at: http://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC71156/jrc71156.pdf (accessed February 15, 2016). Brender, J., Ammenwerth, E., Nykänen, P. and Talmon, J. (2006), “Factors influencing success and failure of health informatics systems: a pilot Delphi study”, Methods of Information in Medicine, Vol. 45 No. 1, pp. 125-136. Coiera, E. (2009), “Building a national health IT system from the middle out”, Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 271-273, doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3183. Cresswell, K.M., Robertson, A. and Sheikh, A. (2012), “Lessons learned from England’s national electronic health record implementation: implications for the international community”, 2nd ACM SIGHIT, Proceeding of the International Health Informatics Symposium in Miami, Florida, USA, ACM, New York, NY, pp. 685-690. Deutsch, E., Duftschmid, G. and Dorda, W. (2010), “Critical areas of national electronic health record programs – is our focus correct?”, International Journal of Medical Informatics, Vol. 79 No. 3, pp. 211-222, doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf. European Patient Smart Open Services (epSOS) (2014), available at: www.epsos.eu/ (accessed June 11, 2014). Fried, B. and Gaydos, L. (2002), World Health Systems: Challenges and Perspectives, Health Administration Press, Chicago, IL. Hoerbsta, A., Kohlb, C., Knaupb, P. and Ammenwerthc, E. (2010), “Attitudes and behaviors related to the introduction of electronic health records among Austrian and German citizens”, International Journal of Medical Informatics, Vol. 79 No. 2, pp. 81-89, doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf. Jerlvall, L. and Pehrsson, T. (2012), “eHealth in Swedish county councils”, inventory commissioned by the SLIT group, available at: http://cehis.se/images/uploads/dokumentarkiv/Rapport_eHalsa_i_ landstingen_SLIT2012_eng_rapport_121019.pdf (accessed March 13, 2014). Kaushal, R., Edwards, A., Kern, L.M. and HITEC Investigators (2015), “Association between electronic health records and health care utilization”, Applied Clinical Informatics, Vol. 28 No. 6, pp. 42-55, doi: 10.4338/ACI-2014-10-RA-0089. Kierkegaard, P. (2013), “eHealth in Denmark: a case study”, Journal of Medical System, Vol. 37 No. 9991, pp. 1-10, doi: 10.1007/s10916-013-9991-y. Lluch, M. (2011), “Healthcare professionals’ organisational barriers to health information technologies – a literature review”, International Journal of Medical Informatics, Vol. 80 No. 12, pp. 849-862, doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf. Ludwick, D.A. and Doucette, J. (2009), “Adopting electronic medical records in primary care: lessons learned from health information systems implementation experience in seven countries”, International Journal of Medical Informatics, Vol. 78 No. 1, pp. 22-31, doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf. McGinn, C.A., Grenier, S., Duplantie, J., Shaw, N., Sicotte, C., Mathieu, L., Leduc, Y., Légaré, F. and Gagnon, M.P. (2011), “Comparison of user groups’ perspectives of barriers and facilitators to implementing electronic health records: a systematic review”, BMC Medicine, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 1-10, doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-46. Monsen, K., Honey, M. and Wilson, S. (2010), “Meaningful use of a standardized terminology to support the electronic health record in New Zealand”, Applied Clinical Informatics, Vol. 1 No. 4, pp. 368-376, doi: 10.4338/ACI-2010-06-CR-0035. Morrison, Z., Robertson, A., Cresswell, K., Crowe, S. and Sheikh, A. (2011), “Understanding contrasting approaches to nationwide implementations of electronic health record systems: England, the USA and Australia”, Journal of Healthcare Engineering, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 25-41, doi: 10.1260/20402295.2.1.25. Mossialos, E., Wenzl, M., Osborn, R. and Sarnak, D. (2016), International Profiles of Health Care Systems, The Commonwealth Fund, New York, NY, p. 180, available at: www.commonwealthfund.org/ ~/media/files/publications/fund-report/2016/jan/1857_mossialos_intl_profiles_2015_v7.pdf (accessed March 20, 2016). OECD/WHO (2011), OECD Reviews of Health Systems: Switzerland 2011, OECD Publishing, Paris, available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264120914-en (accessed April 2, 2013). Sheikh, A., Cornford, T., Barber, N., Avery, A., Takian, A., Lichtner, V., Petrakaki, D., Crowe, S., Marsden, K., Robertson, A., Morrison, Z., Klecun, E., Prescott, R., Quinn, C., Jani, Y., Ficociello, M., Voutsina, K., Paton, J., Bernard, A. and Cresswell, K. (2011), “Implementation and adoption of nationwide electronic health records in secondary care in England: final qualitative results from prospective national evaluation in ‘early adopter’ hospitals”, British Medical Journal, Vol. 343 No. 1, pp. 1-14, doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6054. Stroetmann, K., Artmann, J., Stroetmann, V., Protti, D., Dumortier, J., Giest, S., Walossek, U. and Whitehouse, D. (2011), “European countries on their journey towards national eHealth infrastructures: final European progress report”, European Commission – Information Society and Media – Unit ICT for Health, Brussels, p. 58, available at: www.ehealthnews.eu/images/ stories/pdf/ehstrategies_final_report.pdf (accessed September 8, 2016). Stroetmann, K.A., Jones, T., Dobrev, A. and Stroetmann, V.N. (2006), eHealth is Worth it – The Economic Benefits of Implemented Ehealth Solutions an Ten European Sites, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Brussels, available at: www.ehealth-impact.org/ download/documents/ehealthimpactsept2006.pdf (accessed January 16, 2013). Thomson, S., Osborn, R., Squires, D. and Jun, M. (2013), International Profiles of Health Care Systems, The Commonwealth Fund, New York, NY, p. 138, available at: www.ehealthnews.eu/images/ stories/pdf/ehstrategies_final_report.pdf (accessed March 20, 2013). Tsai, C.Y., Pancoast, P., Duguid, M. and Tsai, C. (2014), “Hospital rounding – EHR’s impact”, International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, Vol. 27 No. 7, pp. 605-615. A nationwide EHR 129 IJHCQA 31,2 130 Further reading Act on secure digital communication and applications in the health care system (E-Health Act) (2015), German Federal Ministry of Heath, available at: www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/health/ e-health-act.html (accessed February 15, 2016). Australian Government (2010), A National Health and Hospitals Network for Australia’s Future – Delivering Better Health and Better Hospitals, Commonwealth of Australia, Barton, p. 82, available at: https:// acnp.org.au/sites/default/files/docs/nhhn_full_report.pdf (accessed May 15, 2016). Dobrev, A., Jones, T., Stroetmann, V., Stroetmann, K., Vatter, Y. and Peng, K. (2010), Interoperable eHealth is Worth it: Securing Benefits from Electronic Health Records and ePrescribing, European Commission – Information Society and Media – Unit ICT for Health, Bonn and Brussels, available at: www.ehealthnews.eu/images/stories/pdf/201002ehrimpact_study-final.pdf (accessed January 16, 2016). Peterburg, Y. (2010), Israel’s Health IT Industry, Israel Trade Commission, Sydney – Australia, available at: http://assets1c.milkeninstitute.org/assets/Publication/ResearchReport/PDF/ IsraelsHealthITIndustry.pdf (accessed January 16, 2016). About the authors Leonidas L. Fragidis received the BSc Degree in Computer Science and the MSc Degree in Communication System from the University of Wales, Swansea, UK, He received another MSc Degree in Finance and Financial Information Systems from the University of Greenwich, UK. He is an IT Professional and a PhD candidate in Democritus University of Thrace, Xanthi. His research interests include health information systems, eHealth, electronic health record implementation, eEducation, quality assurance in higher education, wed development and software engineering. His work has been published in Health Policy and Technology, Technology and Health Care and Scientometrics. Leonidas L. Fragidis is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: lfrangid@pme.duth.gr Prodromos D. Chatzoglou is a Professor of MIS and Business Decisions in the Department of Production and Management Engineering, Democritus University of Thrace, Xanthi, Greece. He received a BA Degree in Economics from Graduate Industrial School of Thessaloniki, Greece, an MSc Degree in Management Sciences and a PhD Degree in Information Engineering both from UMIST, Manchester, UK. His research interests include IS project management, requirements engineering, health information systems, knowledge management, e-Business and strategic management. His work has been published in Information Systems Journal, Decision Sciences, International Journal of Medical Informatics, International Journal of Human Resource Management and Computers and Education. For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com