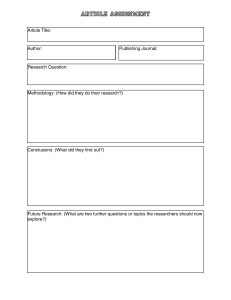

Management Accounting Research 21 (2010) 79–82 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Management Accounting Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mar Issues in the relationship between theory and practice in management accounting Gudrun Baldvinsdottir a , Falconer Mitchell b,1 , Hanne Nørreklit c,∗,2 a b c Gothenburg University, Vasagatan 1, Gothenburg, Sweden University of Edinburgh, William Robertson Building, 50 George Square, Edinburgh, UK Aarhus University, Fuglesangs Allé 4, 8210 Århus V, Denmark a r t i c l e Keywords: Practice Technical core Social science i n f o a b s t r a c t In recent decades the interest of academic researchers in the practical aspects of management accounting has waned. This editorial explores some of the reasons of this development. Over the past few decades we have witnessed the establishment of management accounting in academia as a social science. This has increased the credibility of the accounting academics. However, it has also meant that academic researchers have neglected the technical core of their discipline and its problems and issues which have a direct practical relevance. It is concluded that there is a need for academic researchers to have a stronger focus on the technical core of the subject and to harness the findings of empirical research so that they can be used to develop and support practice. © 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction 2. Contemporary management accounting research The call for papers for this special issue elicited only a very limited response. This probably reflects the academic community’s view that the issue of how research and the development of management accounting theory relates to practice is not particularly important. Contemporary circumstances and pressures may well have downgraded the significance of practical considerations for academics. In this short editorial we suggest some of the reasons why this might have happened and argue that if management accounting research is to maintain its distinctiveness from the other social sciences and disciplines to which it has become linked, there is a need to retain a focus on the technical core of practice. Over the past few decades, there has been a burgeoning growth in management accounting research and in the theory underpinning it (Luft and Shields, 2002; Zimmerman, 2001; Chapman et al., 2007; Malmi and Granlund, 2009). This growth has not been one simply of volume. It has also involved a significant extension of scope both in terms of the research topic and in the theoretical bases employed by researchers. Despite this growth, there has been scant interest shown in research by those involved in the practice of management accounting. One salient exception to this has been the work that has emerged from Harvard by academics such as R. Kaplan and R. Cooper on topics such as activity based costing and the balanced scorecard. This work has taken the form of identifying, developing and promoting solutions to practical problems initially uncovered in case studies of current practice. Consequently it may be viewed as being at the development end of the R and D process. In essence, it is based on the recycling of existing practice. The Harvard work demonstrates that the practitioner will enthusiastically use a certain type of research. Indeed, surveys show it has changed management accounting practice quite significantly e.g., Innes et al. (2000). ∗ Corresponding author. Tel.: +45 8948 6377; fax: +45 8948 6660. E-mail addresses: Baldvinsdottir@handels.gu.se (G. Baldvinsdottir), mitchllf@wrb1.bae.ed.ac.uk (F. Mitchell), hann@asb.dk (H. Nørreklit). 1 Falconer Mitchell also has a visiting position at the University of Aarhus, Denmark. 2 Hanne Nørreklit is also a Professor at NHH, Bergen, Norway. 1044-5005/$ – see front matter © 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.mar.2010.02.006 80 G. Baldvinsdottir et al. / Management Accounting Research 21 (2010) 79–82 Over recent years, management accounting has become an innovative practice and consequently the potential exists for the researcher to play a supportive role in the development of the discipline at a practical level, at least, by assessing the new practices being introduced. In this role, the independence of an academic position can benefit the researcher. However, it is apparent that the wider research community has little interest in influencing practice or in capturing the practitioner as an audience for their output. This is exemplified, in a Netherlands’, public sector context, by the van Helden et al.’s paper which follows in this issue. Most accounting research does not have practical accounting development as an aim. Why should this be so? Is this communication gap between research-based theoretical development and practice important? To answer these questions we must consider the manner in which management accounting research and theory has developed 3. Social science From the 1960s onwards accounting has become firmly established as a social science (Ryan et al., 2002). In the main, this has been achieved by the emphasis its researchers have placed on empiricism. The dominance of positivism in the USA (Zimmerman, 1979; Watts and Zimmerman, 1979, 1986) and the growth in interpretive case study based and survey based research in management accounting throughout Europe (Panozzo, 1997; Drury and Tayles, 1994, 2005) evidence the academic progression of accounting. During this process management accounting’s initial links to economics have been steadily expanded to include such social sciences as sociology, psychology and organisational studies. Further development has been apparent using the disciplines of mathematical analysis and perhaps, most notably philosophy. Seal’s paper in this issue is a case in point utilising both economic theory and discourse analysis to explain the acceptance and use of ideas in practice. These interdisciplinary developments have underpinned the attainment of accounting’s academic credibility. These trends in accounting research are unsurprising given the accounting researcher’s position in an academic environment. They are, however, also likely to create gaps between accounting researchers and practitioners. From a social science perspective the primary aim of accounting research is to explain and understand the behaviour of accountants. Changing (improving) their behaviour, within given institutional settings, is not (certainly in the immediacy) a priority within the research schema of most accounting academics. Embracing the status of social scientists by management accounting researchers has been accompanied by a decline in the logical and normative analyses of practice, e.g., Baxter and Oxenfeldt (1961), Thomas (1974), Solomons (1965) and Anthony (1975), which dominated the research agenda before the late 1970s. In depth analysis of new methods for practice has become relatively rare today, although prominent exceptions do exist e.g., De Haas and Kleingeld, 1999, Norreklit, 2000. It is somewhat paradoxical that intensifying the research focus, through empiricism, on what is happening in practice has apparently resulted in research outputs which practitioners do not find relevant. The theories and practices employed in this push to empiricism do not seem to have explained or illuminated practice in practical ways which possess value for the objects of the research. It seems that the issues for empirical research are derived primarily from the existing research literature as opposed to having an origin in problems of practical relevance. 4. Socio-technical discipline What can the accounting researcher contribute to accounting research that cannot be achieved by the sociologist, economist or philosopher? The answer to this question lies in the socio-technical nature of management accounting. Accounting behaviour involves the interaction of people and accounting techniques. If these accounting techniques are not understood and adequately described by the researcher then the explanations of behaviour generated by research activity are likely to be deficient and potentially misleading. It is the technical aspects of the discipline which give accounting researchers a comparative advantage over social science researchers and enables them to produce explanations of behaviour which they are more specifically capable of producing. Without sufficient attention to the technical core research will lose the stamp of “accounting”. It may be more accurately classified as research in one of the social sciences or other disciplines and its nature will make the possibility of technical prescriptions very problematic. In the “rush” to obtain social science credibility, academic accounting researchers may, in many instances, have somewhat neglected the technical core of their subject. This makes it difficult for the reader to fully interpret the significance of the results and the ways in which research on accounting and practice interrelate. If it is accepted that accounting research should be founded on the discipline’s technical core then one might expect accounting research journals to be replete with extensive and rich descriptions of the practices which constitute the technical aspects of the study. All too often this is not the case. For instance, where budgeting or costing or performance measurement is the focus of study only limited acknowledgement of the technical nature of these practices are included in the research outputs. It may well be true that the social or behavioural nature of accounting has been neglected in the normative analyses of practical techniques which used to dominate the academic literature. However, the converse is now true of much social science or philosophical based investigations of accounting practice. Management accounting research has moved from a predominant focus on the technical to a predominant focus on the social. There has been a neglect of research which seeks to balance both aspects and which therefore reflects the real world nature of the accounting discipline. 5. Empirical research Exhibit 1 outlines the key stages in empirical management accounting research. First, an area or topic of research is selected with suitable empirical evidence identified. Sec- G. Baldvinsdottir et al. / Management Accounting Research 21 (2010) 79–82 Exhibit 1. Stages in empirical research in management accounting. ond, the situation and the behaviour of actors have to be captured through description. Theories can either be developed from the descriptive evidence (e.g., inductions such as grounded theory) or imported theories may be applied to the data that has been gathered. The role of theory is to aid explanation of what has been found empirically. Where the explanation is convincing then it can lead to an understanding of what has been found. It is rare in management accounting for description to provide sufficient substance for research publications (though there are exceptions – e.g., Patell, 1987). Explanation and understanding are what is needed for academic publications, and they have come to be recognised as the primary purpose of academic research. There is no need, nor are there expectations on the part of journal editors or reviewers, that accounting research should generate prescriptions. This does not imply there is no research which encompasses this last stage. However, it remains rare; but, see Kasanen et al. (1993) for the promotion of constructive research (an action research approach) in management accounting and Tuomela (2005) for an example of its application. The production of research which is seen as “applied”, in the sense of providing prescriptions for practitioners, may even have a negative impact on the researcher. The stigma of consultancy-type research is, perhaps too close, for this type of research to have mass appeal in academia. Thus, a prescriptive dimension in management accounting research remains rare, and it is generally unnecessary for the publication of research output. 6. Aims of empirical research Empirical research in management accounting may be viewed as a continuum. At one extreme research may be designed to explain and understand practice as it is found in the real world. In such research there would be no intention of influencing practice through research. The practitioner would be treated solely as a research object and researcher would not be influenced by the pressures of justifying the findings in terms of immediate practical relevance. This does not imply that this type of research will have no influence on practice. It is to be hoped that prescriptions for practice will be based on sound understanding of the behaviours and circumstances to which they relate. Ultimately, therefore, it might be hoped that research of this 81 type will possess some relevance for the guidance of practice. However, there is a need to harness the findings of research of this type so that they can be used by those who make prescriptions for practice. For example, what guidance might contingency theory studies contribute for the practitioner who compares his/her management accounting system to those of other organisations? Can it assist in identifying potential practical strengths and weaknesses? How can research in management accounting change help practitioners who face the challenge of changing their systems? Can it lead to good predictions of how staff will react to changes? Can it suggest actions that can be taken to improve the likelihood of change being successful? The translation of research into practical guidance remains a challenge (see van Helden et al.’s paper in this issue) as the practitioner lacks the time and skills for this task, especially when he/she is confronted by all the challenges of the mathematical, statistical and theoretical aspects of accounting research. These aspects may enhance the scientific nature of the work, but they can also compromise its accessibility outside of academia. Academic careers can also mean that the academic researcher has no motive to prescribe (unless, for example, research funding becomes linked to demonstrating research impact). Unless some mechanism is found to address this issue, research and practice in management accounting are likely to exist independently, i.e., without any provider-user linkage. Furthermore, if research is produced by academic researchers for other academic researchers then the research loop becomes closed within the academic community. If explanation and understanding are taken as ends in themselves, it may be difficult to justify accounting research outside of the academic community and, as a consequence, to properly assess its significance. The result is likely to be a knowledge application gap; i.e., a gap between theories of knowing and knowing what action needs to be taken (Pfeffer and Sutton, 1999). Academic research will be the poorer for the exclusion of practitioner judgements as practitioners are an intelligent audience with the capacity to provide correction and guidance. At the opposite extreme of the research continuum lies interventionist research which is intended to contribute directly to changing and developing practice. While this offers potential for prescription it does not have a prestigious position in the academic research community and is pursued by only a minority of accounting researchers. This is because, as van Helden et al acknowledge, it lies in the grey area where research and consultancy meet. Essentially, it can take two forms. First, it may be constructive in nature (Kasanen et al., 1993) and designed to solve practical problems with much the same ethos as action research. van Helden et al.’s paper suggests that work of this nature (deemed knowledge creation rather than research) falls within the remit of the consultant/researcher who fulfils an important role in the public sector context. Alternatively, it may involve the researcher playing a role similar to that of “theatre” critic; identifying where management accounting practice has deficiencies. Seal, in his paper in this issue, concludes that it is in the twinning of these roles that the management accounting researcher may find a niche to enhance practice in the discipline. 82 G. Baldvinsdottir et al. / Management Accounting Research 21 (2010) 79–82 7. Research agenda The research agenda in management accounting has, in recent times, emphasised a social science and interdisciplinary based empiricism. This has fostered the attainment of academic credibility for the discipline. There has been a focus on finding out about behaviour in the practical world as opposed to deriving guidance for practice. The conclusions drawn from such studies are for further research, rather than for practice. As a result, practical learning from research, from its theories and from its interdisciplinary links, has been missing from much of the management accounting research agenda. This absence is an important one if the ultimate purpose of social science research is to improve life (rather than simply to describe and/or understand it). If the former objective (of improving life) is accepted, at a minimum the research findings and theoretical understandings should to be applied to the benefit of management accounting practice. References Anthony, R.N., 1975. Accounting for the Cost of Interest. Lexington, Mass., USA. Baxter, W., Oxenfeldt, A.R., 1961. Costing and Pricing: The Cost Accountant versus the Economist, Business Horizons, 4, 4, 77–90, (reprinted in Studies in Cost Analysis, In: D. Solomons (Ed.), Sweet and Maxwell, London, 1968). Chapman, C.S., Hopwood, A.G., Shields, M.D., 2007. Handbook of Management Accounting Research. Elsevier, Amsterdam. De Haas, M., Kleingeld, A., 1999. Multilevel design of performance measurement systems: enhancing strategic dialogue throughout the organization. Management Accounting Research 10, 233–261. Drury, C., Tayles, M., 1994. Product costing in UK manufacturing organisations. The European Accounting Review 3 (3), 443–469. Drury, C., Tayles, M., 2005. Explicating the design of overhead absorption procedures in UK organisations. British Accounting Review 37, 47–84. Innes, J., Mitchell, F., Sinclair, D., 2000. Activity-based costing in the UK’s largest companies: a comparison of 1994 and 1999 survey results. Management Accounting Research 11, 349–362. Kasanen, E., Lukka, K., Siitonen, A., 1993. The constructive approach in management accounting research. Journal of Management Accounting Research 5, 243–264. Luft, J.L., Shields, M.D., 2002. Zimmerman’s contentious conjectures: describing the present and prescribing the future of empirical management accounting research. European Accounting Review 11. (4). Malmi, T., Granlund, M., 2009. In search of management accounting theory. The European Accounting Review 18 (3), 597–620. Norreklit, H., 2000. The balance on the balanced scorecard—a critical analysis of some of its assumptions. Management Accounting Research 11, 65–88. Panozzo, F., 1997. The making of the good academic accountant. Accounting Organisations and Society 22 (5), 447–480. Patell, J.M., 1987. Cost accounting, process control and product design: a case study of the Hewlett-Packard personal office computer division. The Accounting Review 62 (4), 808–839. Pfeffer, J., Sutton, R.I., 1999. Knowing what to do is not enough: turning knowledge into action. California Management Review (Fall), 83–108. Ryan, R., Scapens, R.W., Theobald, M., 2002. Research Method & Methodology in Finance & Accounting. Thomson, London, UK. Solomons, D., 1965. Divisional Performance: Measurement and Control. Richard D Irwin, Illinois, USA. Thomas, A.L., 1974. The Allocation Problem: Part Two. American Accounting Association. Tuomela, T., 2005. The interplay of different levers of control: a case study of introducing a new performance system. Management Accounting Research 16 (3), 293–320. Watts, R., Zimmerman, J., 1979. The demand for and supply of accounting theories. The market for excuses. The Accounting Review 59, 273–305. Watts, R., Zimmerman, J., 1986. Positive Accounting Theory. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Zimmerman, J., 1979. The costs and benefits of cost allocations. The Accounting Review 54, 504–521. Zimmerman, J., 2001. Conjectures regarding empirical management accounting research. Journal of Accounting and Economics. 32 (1–3), 411–427.