The Enchantment of Art: Abstraction and Empathy from German Romanticism to

Expressionism

Author(s): David Morgan

Source: Journal of the History of Ideas , Apr., 1996, Vol. 57, No. 2 (Apr., 1996), pp. 317341

Published by: University of Pennsylvania Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3654101

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3654101?seq=1&cid=pdfreference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

University of Pennsylvania Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Journal of the History of Ideas

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Enchantment of Art:

Abstraction and Empathy

from German Romanticism

to Expressionism

David Morgan

A familiar tradition since the eighteenth century has invested art with the

power to heal a decadent human condition. Inheriting this ability from

religion-the romantic enthusiast Wilhelm Wackenroder considered artistic

inspiration to originate in "divine inspiration" in the case of his hero,

Raphael'-art eventually replaced institutionalized belief in an evolutionary

schedule of cultural development determined by German idealism. Hegel, for

instance, theorized the evolution of spirit from religion to art as a qualitative

advancement over time. Rejecting the metaphysics of German idealism,

Friedrich Nietzsche nevertheless contended that "Art raises its head where

religions decline." By assuming the "feelings and moods" of religion which

had been dismantled by enlightenment, Nietzsche claimed that art gave new

form to the life of feeling and imbued human endeavors with a "loftier,

darker coloration."2 In the early twentieth century Wassily Kandinsky believed that the "spiritual in art" was the historical manifestation of an "inner

necessity" that was in itself timeless and universal. Kandinsky portrayed the

"life of the spirit" as "a large acute-angled triangle divided horizontally into

unequal parts." In a kind of "trickle down" aesthetic, the compartments of

the triangle move slowly upward toward the apex, which is inhabited by the

solitary genius of an age whose vision gradually elevates all those who

occupy the lower stages.3

t Wilhelm Wackenroder, Confessionsfrom the Heart of an Art-Loving Friar, 1796, in

Confessions and Fantasies, tr. Mary Hurst Schubert (University Park, Penn., 1971), 83.

2 Friedrich Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits, tr. Marion

Fabor with Stephen Lehmann (Lincoln, 1984), 105 (? 150).

3 Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, tr. M. T. H. Sadler (New York,

1977), 6-7.

317

Copyright 1996 by Journal of the History of Ideas, Inc.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

318

David Morgan

The point for proponents of the spiritual in art from romanticism to

expressionism (and beyond) was to find in works of art what can best be

described as an enchantment.4 As the negotiation of the gaps or disjunctures

separating human beings from complete power over their lives, enchantment

conjoins the plane of immediate human experience to a desirable state of

affairs through the mediation of such symbolic devices as rituals, incantations, or charms. Thus, evil can be warded off by the use of an apotropaic

amulet, and fertility can be enhanced by the recitation of a suitable prayer or

the performance of a certain ritual. In a modem analogy a sense of impotence

is often alleviated by a trip to the mall where the bored therapeutically lose

themselves in symbolic acts of self-renewing consumption. In the traditions

of philosophy and science, systems of representation such as astrology, the

microcosm, the harmony of the spheres, the great chain of being, the celestial

hierarchies, or the mechanisms of theurgy and divination situate humanity

within a cosmos that follows a particular order accessible to and in some

degree manipulable by human beings. Enchantment consists of an apparatus

of belief whose form of representation or enactment is thought to exert

influence over the realities it configures.

But enchantment is not limited to the spells and magic of premodern

metaphysics (or modem consumerism). By means of religion, morality, and

aesthetics, Nietzsche once averred, "man likes to believe that ... he is

touching the heart of the world."5 This study will focus on the manner in

which art as constructed within the idealist tradition of German art theory

functioned as an enchantment. Specifically, it will explore what the history of

ideas about abstraction and empathy has to tell us about the spiritualization or

enchantment of art. After identifying the philosophical and aesthetic wherewithal of enchantment in nineteenth-century Germany, attention focusses on

Franz Marc's early twentieth-century theorization of abstraction. It is certainly more customary to study Kandinsky, whose writings and early efforts

at abstraction are much better known, but Marc's ideas offer more immediate

connections to German intellectual history and clarify the aims of his abstract

art as a strategy of enchantment. Moreover, Marc was unusually articulate

and wrote often, exploring ideas and artistic efforts with great insight.

Focusing on Marc therefore offers a corrective to the historiography that has

favored Kandinsky's writings. Finally, Marc differed from his Russian friend

over the cause of the war. Manifesting a difference that is portentous for this

study, Kandinsky left Germany for Russia in 1914, while Marc enthusiastically took up arms for the fatherland. Given these circumstances and the

unfortunate tendency of art historians to valorize expressionist art rather than

situate it in the ideological context of its production, it is time to delimit more

precisely than has usually been done what Marc sought to do and how it

4 On the role of enchantment in the history of scientific hermeneutics see Mark A.

Schneider, Culture and Enchantment (Chicago, 1993). For a contemporary advocacy of

enchantment in art see Suzi Gablik, The Reenchantment of Art (New York, 1991).

5 Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human, 16 (?4).

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

319

The Enchantment of Art

related to a nineteenth-century history of thought that has exercised enormous influence on the visual and creative culture of enchantment in European

and American society in the twentieth century.

Strategies of Enchantment:

Abstraction and Empathy from Schopenhauer to Marc

In the eighteenth century abstraction in the creation of a work of art was

generally defined as the determination of the essence of a thing.6 The artist

was thought to arrive at this essence by a process of generalization whereby

particulars were eliminated until only a subject's generic, universal quali-

ties-its essence-remained. It was this view that informed Hegel's discussion of the artist's treatment of the "essence" or "universal idea" and

Schopenhauer's assertion that the individual was raised to the "Idea of its

species" in aesthetic contemplation. Yet Hegel and Schopenhauer created

idealist philosophies which were distinguished by virtue of a peculiar interpretive value, a capacity to account in a sweeping manner for the human

condition and in a way that gave art a central importance. Hegel worked out a

dynamic of history in which Geist or spirit drew ever closer to its ultimate

self-expression and characterized in its development the historical ages of

mind that allowed Hegel and his contemporaries to locate themselves in the

final dispensation. "May the kingdom come," he wrote to Schelling, "and

may our hands not be idle."7 A darker vision animated Schopenhauer's

lamentation on the will as the basis of suffering. All existence groans and the

only redemption is to recognize the true nature of things and to pursue the

transcendence of art or the path of the ascetic. Each in his own way, Hegel

and Schopenhauer offered an immediate revelation of true being in art. It was

the concrete immediacy of this other that distinguished German romantic

idealism. The enchantment of romanticism was that the absolute was not

strictly absolute but immanent in nature, in the human self, and in the work of

art.

For Schopenhauer the art work disclosed the eternal platonic form under-

lying appearances. Thus, "the object of aesthetic contemplation is not the

individual thing, but the Idea in it striving for revelation."8 Knowledge of the

6 See David Morgan, "The Rise and Fall of Abstraction in Eighteenth-Century Art

Theory," Eighteenth-Century Studies, 27 (1994), 449-78.

7 Quoted in Walter Schmithals, The Apocalyptic Movement: Introduction and Interpretation, tr. John E. Steely (Nashville, 1975), 230. Schmithals writes of Hegel's view:

"This kingdom of the divine Spirit is actualized in history, and the eschatological

judgment of the world coincides with the history of the world as a whole" (ibid.). See also

M. H. Abrams, "Apocalypse: Themes and Variations," in The Apocalypse in English

Renaissance Thought and Literature, ed. C. A. Patrides and Joseph Wittreich (Ithaca,

1984), 360-62; and Karl L6with, From Hegel to Nietzsche: The Revelation in NineteenthCentury Thought, tr. David E. Green (Garden City, N.Y., 1967), 29-49.

8 Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation, tr. E. F. J. Payne (2

vols.; Indian Hills, Col., 1958), I, 209.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

David Morgan

320

Idea is the aim of all art, according to Schopenhauer, and such knowledge is

achieved only by passing out of the contingency of space and time. This

occurs when we

devote the whole power of our mind to perception, sink ourselves

completely therein, and let our whole consciousness be filled by the

calm contemplation of the natural object actually present, whether it

be a landscape, a tree, a rock, a crag, a building, or anything else. We

lose ourselves entirely in this object ... we forget our individuality,

our will, and continue to exist as pure subject, as clear mirror of the

object, so that it is as though the object alone existed without anyone

to perceive it, and thus we are no longer able to separate the perceiver

from the perception, but the two have become one.... Now in such

contemplation, the particular thing at one stroke becomes the Idea of

its species, and the perceiving individual becomes the pure subject of

knowing. The individual, as such, knows only particular things; the

pure subject of knowledge knows only Ideas. (178-79)

The legacy of German idealism persisted throughout the nineteenth

century. The work of such philosophers and aestheticians as Friedrich

Theodor Vischer and Eduard von Hartmann was fundamentally indebted to

Schopenhauer, Schiller, and Hegel. Schopenhauer's philosophy was also

vital to Nietzsche in the early 1870s, when his first published works defended

direct access to the "primordial will" that he found embodied in Wagner's

music.9 In 1907 Georg Simmel published his Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, in

which he gave a long chapter to Schopenhauer's "Metaphysik der Kunst."'0

Schopenhauer's concept of self-alienation in aesthetic contemplation played

a particularly important role in the early work of someone who had attended

Simmel's lectures as a student in Berlin, the art historian Wilhelm Worringer.

In his well-known Abstraction and Empathy (1908), Worringer drew an

explicit analogy between his description of the transcendental inclination of

the abstract Kunstwollen or artistic volition and Schopenhauer's discussion

of escape from the realm of blind will by contemplative immersion in the

work of art."l Before we can fully assess the idealist components of

Worringer's thought, however, it is necessary to examine the development of

empathy as a legacy of idealism.

9 See Nietzsche's Die Geburt der Tragodie (1872) and Schopenhauer als Erzieher

(1874), and, on Nietzsche's debt to Schopenhauer, Julian Young, Nietzsche's Philosophy of

Art (Cambridge, 1992).

10 Georg Simmel, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, trs. Helmut Loiskandl, Deena

Weinstein, and Donald Weinstein (Urbana, Ill., 1991).

1 Wilhelm Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy, tr. Michael Bullock (London, 1963),

33, note. Worringer's admiration for Simmel is evident (ix) in the foreword he wrote for the

1948 edition of Abstraction and Empathy, where he remembers a chance encounter with

Simmel in Paris during his student years.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Enchantment of Art

321

Implicit in Schopenhauer's account of contemplative absorption in art is

a concept of empathy that went on to become one of the major themes in

nineteenth-century German aesthetics. Two broad phases in the history of

empathy theory should be distinguished. The first consisted of an enthusiastic aesthetic experience which sought to break down the distinction between

subjective feeling and objective realities, an experience often described in

pantheistic terms. The second phase represents the attempt to construct a

theory of perception in which human feeling is projected into forms through

the eye's constructive acts of visual interpretation.

In the first phase art was regarded as an affective, pantheistic, fundamentally romantic fusion of the soul with nature. The romantic poet Novalis had

claimed at the beginning of the nineteenth century that no one could grasp

nature who did not possess an "organ for nature" which, with an inner

affinity with all things, "mixes itself through the medium of feeling into all

natural entities, as it were, feels itself into them."'2 This idea persisted

among empathy theorists in Germany. In 1876 the young aesthetician

Johannes Volkelt expressed the enchantment of the pathetic fallacy: "When I

feel my soul from out of the wind and clouds, the mountain and heath, the

illumination of morning and evening, the presentiment penetrates me that

nature is spirit of my spirit, that there is in the strictest sense no duality in the

world."13

The most renowned advocate of empathy, Theodor Lipps, followed

Heinrich W6lfflin in eliminating Volkelt's pantheistic monism from the

treatment of empathy as a psycho-perceptual process. Lipps was instrumental

in putting in place the second major understanding of empathy in the nine-

teenth century.'4 In an essay of 1900 he sought to describe empathy as a

psychological function fundamental to aesthetic experience. He characterized

it as an "animation" of an object which becomes a mirror of the viewer's

personality. According to Lipps, "Aesthetic harmony is grounded in the

harmony of the personal and the foreign...."5 Empathy is a working out of

one's relations with the objective world by means of objectifying oneself.

"Aesthetic sympathy means this: to experience and feel oneself in another, at

12 Quoted in Paul Ster, Einfihlung und Association in der neueren Aesthetik. Beitrage

zur Aesthetik, V (Hamburg, 1898), 3.

13 Johannes Volkelt, Der Symbol-Begriff in der neuesten Aesthetik (Jena, 1876), 114.

14 Heinrich Wolfflin, "Prolegomena zu einer Psychologie der Architektur," Kleine

Schriften, ed. Joseph Gantner (Basel, 1946), 13-47; translation in Empathy, Form, and

Space: Problems in German Aesthetics, 1873-1983, intro. and tr. Harry Francis Mallgrave

and Eleftherios Ikonomou (Santa Monica, 1994). See also Wilhelm Perpeet, "Historisches

und Systematisches zur Einfuhlungsaesthetik," Zeitschrift fur Aesthetik und allgemeine

Kunstwissenschaft, 11 (1966), 193-216, and for a discussion of Theodor Friedrich Vischer

and Robert Vischer, see Mallgrave and Ikonomou, "Introduction," 17-29.

15 Theodor Lipps, "Aesthetische Einfiihlung," Zeitschrift fur Psychologie und

Physiologie der Sinnesorgane, 22 (1900), 426.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

322

David Morgan

the same time in as characteristically intensified, pure, and free a manner as

the nature of the aesthetic object brings with it. Aesthetic enjoyment based on

this is the felicitous feeling of the objectified self."'6 This notion of empathy

inverted the kenosis or self-emptying of Schopenhauer's aesthetic contemplation. The presence in the work of art was ultimately the presence of one's

own self, the animation of otherness with the viewer's ego. As the concept of

empathy became more circumscribed within the bounds of perceptual psychology, the aspect of identity shifted from a pantheistic-ontological unity of

mind and nature to an epistemological imperialism of the human personality

responsible for overcoming all otherness, all difference with its powers of

animation.17 The experience of enchantment was replaced by a scientific

explanation of human feeling and perception.

But the two strands of idealist thought under consideration here-abstraction and empathy-were interwoven in Worringer's aptly titled Abstrac-

tion and Empathy. Worringer's attempt at a "psychology of style" combined

the nineteenth-century study of perception with a philosophical sensibility

colored by Schopenhauer. Worringer contended that the use of abstract line

in geometrical ornament offered comfort to primitive humanity because it

excluded all traces of organic life-that is, the change, growth, and decline

which made for an insecure and finite human existence.'8 Abstract form

created in the space of aesthetic experience a dimension composed of necessity and absolute, immutable regularity, which provided a refuge from the

"caprice" of the organic world (34-35). This yearning for the transcendent

corresponded to an abstract artistic volition or Kunstwollen. Worringer contrasted abstraction with empathy, which he defined after Lipps as the enjoy-

ment of the self projected into an object or form. Worringer repressed or

ignored empathy theorists such as Volkelt, whose thought exhibited an

important debt to idealist metaphysics. Limiting Lipps's empathy to organic

forms and identifying the "abstract Kunstwollen" as the impulse toward

geometrical, inorganic, crystalline forms, Worringer claimed that these forms

denied life because the viewer does not find in them the biomorphic design

which conforms with the design of one's own body.

16 Ibid., 432-33. Lipps was indebted to Robert Vischer's phenomenology of feeling in

Ueber das optische Formgefihl (Leipzig, 1873). Compare Vischer's statement with Lipps:

"To trace the outline of a form is a self-movement, an act that is predominantly subjective:

the form being no more than an arbitrary, willful, and unilateral means by which the body

can enjoy itself" (Mallgrave and Ikonomou, Empathy, Form, and Space, 107). But Lipps

moved beyond the idealist metaphysics which still informed Vischer's influential doctoral

dissertation; Vischer's paper is translated in Empathy, Form, and Space, 89-123.

17 Cf. Lipps, Grundlegung der Aesthetik (2 vols.; Hamburg, 1903-5), I, 106: "Der

'Andere' ist die vorgestellte und je nach der ausseren Erscheinung und den wahmehmbaren

Lebensausserungen modifizierte eigene Pers6nlichkeit, ein modifiziertes eigenes Ich. Der

Mensch ausser mir, von dem ich ein Bewusstsein habe, ist eine Verdoppelung und zugleich

eine Modifikation meiner selbst."

18 Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy, 19-21.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

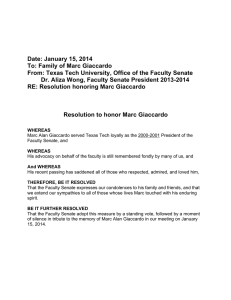

Fig. 1: Franz Marc, "Small Blue Horses," 1911, oil on canvas, 61.5 x 101 cm. Reprinted by permission

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

324

David Morgan

The influence of Worringer's dissertation on German expressionists,

particularly the artists of the Blue Rider, is customarily regarded as considerable. Many have even claimed for it the status of a manifesto.'9 While this is

dubious at best, Karsten Harries's claim that the book "suggested that the

situation of modem man demanded an abstract geometric art" seems an

accurate estimation of the book's significance.20 Early in his book Worringer

observed a parallel between "primitive" and modem humanity. Because the

primitive stood "so lost and spiritually helpless amidst the things of the

external world," he aspired to what Worringer characterized as the "thing in

itself."21 Likewise, though from the intellectual perspective of Kant's

criticial idealism, the modern indulges a "feeling for the 'thing in itself'"

when he refuses to accept phenomena as absolute reality but instead sees in

the visible world, as Worringer quoted Schopenhauer, "the work of Maya,

brought forth by magic, a transitory and in itself unsubstantial semblance,

comparable to the optical illusion" (18). The art of the modern world,

Worringer suggested, shares the abstract Kunstwollen of the primitive.

Yet the question remains just what abstract meant. In fact Worringer did

not intend by abstract the non-objective painting which Kandinsky and others

pursued only a few years later. In Abstraction and Empathy Worringer

praised the ancient Egyptians as those who "carried through most intensively

the abstract tendency in artistic volition" (42). Worringer regarded style as a

synonym for abstraction, and he contrasted style with naturalism in the same

manner that he opposed abstraction to empathy (26). The primary aim of

abstraction was to transcend nature by denying space in representation, as

Riegl had observed. Under the rubric of style Worringer included all artistic

expression whether representational or not-Gothic architecture, primitive

ornament, ancient relief sculpture-which was directed by this denial of

space and use of inorganic forms. Style, like abstraction, meant anything

anti-naturalistic, any art which did not function expressively through empathy. It seems clear, therefore, that Worringer's study was not a brief for non-

representational art.

As for Marc, the evidence is secure that he admired Worringer's general

thesis. In an essay published in PAN in March of 1912 Marc singled out

Abstraction and Empathy and Kandinsky's Concerning the Spiritual in Art

for unique praise.22 In a group of aphorisms written early in 1915 Worringer's

discussion of abstraction was probably in Marc's mind when he compared

19 Peter Selz, German Expressionist Painting (Berkeley, 1974), 8, calls Abstraction

and Empathy "almost the official guide to expressionist aesthetics"; Ulrich Weisstein,

"Expressionism: Style or 'Weltanschauung,'" Criticism, 9 (1967), 52, refers to it as the

"aesthetic Bible of Expressionism."

20 Karsten Harries, The Meaning of Modern Art: A Philosophical Interpretation

(Evanston, Ill., 1968), 69.

21 Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy, 18.

22 Franz Marc, Schriften, ed. Klaus Lankheit (Cologne, 1978), 107. When no date

follows a Marc citation, this indicates the 1978 edition of his Schriften.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Enchantment of Art

325

the "pure will to the abstract" in tribal art with the modem European "will

to abstract form" (210). Furthermore, it is attractive to parallel Worringer's

ideas of abstraction and empathy with the development in Marc's art and

thought from an earlier affinity with empathy to a later preference for

abstraction. Yet this relationship must be carefully modified for Marc's

conception of empathy was not restricted to Worringer's or to Lipps's. In the

work he produced in 1911 before the influence of cubist and futurist art

(which he would shortly see in Berlin and in organizing the Blue Rider

exhibition) Marc celebrated animal life in the landscape in a way that recalls

the monistic-pantheistic version of empathy theorized by Volkelt. Work such

as Small Blue Horses (fig. 1) organizes animal and landscape into rhythmic

configurations whose curvaceous, rolling forms merge, fusing figure and

ground, and then dissolve the unity into gaseous swirls. This pulse of

formation and dissolution characterizes Marc's pictures of animal life at this

time, which, he wrote in 1910, were informed by "a feeling for the organic

rhythm of all things, a pantheistic feeling of oneself into the quivering and

flowing blood of nature, in the trees, in the animals, in the air" (Marc 98).

In a matter of one or two years Marc went from yearning to feel the life in

nature to creating images that violently dismantled the animal and its happy

existence in the landscape. By 1912-13 he understood the artist's task to be to

escape from all forms of anthropomorphic appropriation of the animal's

autonomous being. "We must unlearn from now on to relate animals and

plants to ourselves and to portray in art our relation to them" (113, emphasis

added). Instead-and here Worringer's notion of primitive mankind's longing for the "thing in itself" comes to mind-the artist must strive to see

things "as they really are," shorn of the categories of human knowledge

(112). Marc became unable to accept empathy as a means of enchantment

because he came to see it as only a projection of anthropomorphic interests.

As with Worringer, Schopenhauer's quest for the transcendence of human

reason in the aesthetic revelation of the Idea came to inspire him.

Yet Marc was not of one mind on this as the war opened and the call to

arms seized Germany. In the final stage of his abbreviated life (he died at

Verdun in 1916) Marc vacillated between an essentialism taken to its logical

extreme by scorning nature in abstract painting, on the one hand-and a

patriotic empathy with the blood and soil of the fatherland represented in the

animal and landscape subject matter of his art, on the other. Accordingly,

Marc's oft-quoted statement in a letter of 1915 that his art became more and

more abstract "out of an inner compulsion" as he came increasingly to

recognize the "ugliness and impurity of nature," which is often interpreted

as consistent with Worringer's view that the abstract artistic drive originated

in an antipathetic attitude toward nature,23 must be balanced against his

patriotic interpretation of Germany's military struggle with the Allies.

23 Franz Marc, Briefe aus dem Feld (Berlin, 1948), 64.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

326

David Morgan

The Rhetoric of Enchantment: Marc's Struggle for the Absolute

The expressionist aesthetic was premised on the rejection of naturalistic

representation because it implied the restriction of the artist to the "seen,"

what the young poet and critic Kasimir Edschmid called the "chain of facts,"

the positivist's building blocks of truth and reality.24 In an essay of 1912

Marc contrasted contemporary painting to the art of the nineteenth century

which, he wrote, was "carried to the grave in a small coffin: the camera"

(Marc 105). Marc asserted that the new art "takes the opposite direction than

all earlier movements, where volition and ability strove for ever greater

accord with the external image of nature, which banished with its bright light

of day the secret and abstract conceptions of the inner life" (105).

The "bright light of day" was an obvious reference to impressionism,

the artistic style which avant-garde voices in Marc's day identified as the

culmination of nineteenth-century naturalism. Critics directed their polemics

against impressionistic naturalism because it had come to dominate the

marketplace and exhibition system. Marc and others made use of a militarist

rhetoric of violent struggle to characterize their opposition to the old and their

search for the new. In the 1912 essay on "The Constructive Ideas of the New

Painting" Marc considered the rejection of extraneous or "foreign elements" (Fremdkorper) from the picture to constitute "the Great Revolution." He went on to maintain that the painter no longer depended on the

image of nature but destroyed (vernichtet) it in order to disclose the "power-

ful laws which rule behind beautiful appearances" (Marc 108). This use of

military rhetoric, which is consistent with the pervasive militarization of the

German middle class in the years leading up to World War I, should not be

misconstrued as a flat expression of Marc's artistic intentions.25 Instead, the

military trope adorns his pictures with a polemical character directed against

naturalistic painting. The fact is that at the time he wrote this, Marc's

painting was not at all-indeed, virtually never would be-non-objective. In

1912 he manifested the first tendencies toward the geometric abstractions of

Parisian art. As a result, the impassioned military rhetoric of the passage

depicts an inimical, embattled relationship between art and nature rather than

the final vanquishing of either foe.

Marc more frequently expressed this antagonism in another metaphor:

the opposition of an inner and an outer side of objects, which he joined in an

increasingly violent tension. The inner side was an aspect of reality governed

by its own laws rather than those of the outer, phenomenal side of things.

Marc developed this scheme in an essay entitled "The New Painting." In a

24 Kasimir Edschmid, "Expressionismus in der Dichtung," Die Neue Rundschau, 1

(1918), 364.

25 See Gerhard Ritter, The Sword and the Sceptor: The Problem of Militarism in

Germany, tr. Heinz Norden (2 vols.; Coral Gables, Fla., 1988), II, 93-104.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Enchantment of Art

327

familiar pattern of expressionist polemic, he contrasted modern painters to

"impressionists and plein-air painters of the nineteenth century."

Today we seek beneath the veil of appearances the hidden things in

nature, which seem more important to us than the discoveries of the

impressionists.... And, indeed, we seek and paint this inner, spiritual

side of nature not out of whim or desire for something different, but

because we see this side just as they "saw" violet shadows and

aether over all things. (Marc 102)

Two weeks later Marc published further meditations on the concept of

the "inner side" and asserted that opposition to "naturalistic form" was the

consequence of a deeper will that he claimed permeated the present generation: the urge to investigate metaphysical laws (106). Art, Marc believed, had

the ability to manifest the imperceptible, metaphysical essence of a thing, its

"absolute" or "abstract" being, the "true form" that was left behind when

appearances were completely removed (113). For Marc the task was to

withdraw from art the prejudices of human perception by rejecting mimesis

as an anthropomorphic mode of representation-in effect, to achieve a

manner of empathy that transcended human feeling altogether in favor of the

local feeling of another (nonhuman) being. He delineated this aim as the very

definition of "abstract art" in an important group of notes written in the

winter of 1912-13:

What we understand by "abstract" art.... It is the attempt {and

yearning to see and depict the world no longer with the human eye

but} to bring the world itself to speaking.... Art is, will be, metaphysical; it can be today for the first time. Art will free itself from

human purposes and human will. We no longer paint the forest or the

horse as they please us or appear to us, but as they really are, as the

forest or horse feels itself, its {abstract} absolute essence lives

behind the phenomenon, which we only see....26

Marc wrote that things contain their own will and form and that they

speak among themselves, and this led him to declare: "Why do we want to

interrupt? We have nothing intelligent to say to them" (Marc 113). Objects

become muter the more "we hold before them the optical mirror of their

appearance." By using this metaphor of a language of nature, Marc stressed

the autonomy of nature's underlying forms, its inherent integrity. The artist

was not to impose art on nature, but to penetrate to the essence of things

where nature speaks for itself. By emphasizing nature's own power of speech,

Marc sought to circumscribe humanity's reliance on its own perceptual habits

26 Marc, Schriften, 112 (brackets enclose original text which Marc crossed out;

emphasis in original).

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

David Morgan

328

Fig. 2: Franz Marc, "Deer in the Forest, II," 1914, oil on canvas, 129.5 x 100.5 cm.

Reprinted by permission of the Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Enchantment of Art

329

in a way that calls to mind Schopenhauer's desired transcendence of reason

(principium individuationis) in the mystical experience of aesthetic contemplation. Schopenhauer had characterized the problem of self-transcendence in

optical terms. In the state of "pure, will-less knowing," he wrote, "[w]e are

only that one eye of the world which looks out from all knowing creatures"

(I, 198). It was in this state that knowledge became absolute, free of all

relations, and therefore a disclosure of the platonic idea. According to

Schopenhauer, this vision occurs when the "pure subject of knowing gazes

through [the] struggle of nature" (I, 204), what he called the "permanent

battlefield" of the world, the "unending conflict" of the will individuated in

all phenomena (I, 265). Marc agreed:

We depend no longer on the image of nature, but destroy it, in order

to show the powerful laws which reign behind beautiful appearances.

As Schopenhauer put it, today the world as will is more important

than the world as representation. (Marc 108)

Marc held in common with Schopenhauer a deep appreciation of the suffer-

ing and turmoil that characterized existence as a whole. According to

Schopenhauer, all things are manifestations of a universal will struggling to

fulfill itself in the individual purposes directing each thing. Humans achieve

momentary deliverance from this blind striving of the will in the blissful

absorption of aesthetic contemplation. The degree to which Marc came to

regard nature as a struggle is evident in his militant rhetoric of revolution,

destruction, and the penetration beneath the surface of appearances to the

hidden metaphysical interior.

As his written reflections in 1912 and after indicate, Marc aspired to

depict objects as non-materialistic, as transparent to underlying or inner

dimensions hidden by conventional pictorial devices. He was seized by the

presentiment that nature was much more than the opaque surfaces portrayed

by naturalistic art. Abstraction was the pictorial means for getting at a

hitherto imperceptible reality. Marc proceeded to visualize the penetration of

the veil of appearances by an aggressive altercation between representational

and non-representational forms. The linkage of these two aspects replaced the

priority of the mimetic relationship of the image to visible phenomena but

did so without pursuing a purely non-objective art. For Marc to have forsaken

external reality entirely would have precluded the visual sensation of penetrating into the concealed interior of his subjects. It was just this enterprise

of disclosure which was so important to him, as suggested by his repeated use

of the term "durchschauend" or "looking-through" to describe his manner

of viewing the world of objects.27 Nature was not completely surrendered or

annihilated, but seen-through, visually infiltrated and, therefore, sustained as

27 See the letters of 24 December 1914 and 12 April 1915 (Marc, Briefe aus dem Feld,

41 and 65), and Marc, Schriften, 170; also 195, ?35, where Marc distinguished

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Fig. 3: Franz Marc, "Struggling Forms," 1914, oil on canvas, 91 x 131.5 cm. Reprinted by permission of Sta

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Enchantment of Art

331

indispensable to artistic expression. The presence he sought was the absolute

in the act of becoming present.

The 1914 oil painting Deer in the Forest II (fig. 2) makes this eminently

clear. In this work the organic vitality of Small Blue Horses (fig. 1) has given

way to dissected, angular forms which somewhat unevenly compress the

nebulous space of former years into a fractured geometry clinging to the

picture surface. Marc achieved the revelatory clash of inner and outer aspects

in such visual devices as the stark contrast of surface and depth; by merging

the vertical line from the upper left with the left contour of the deer in the

foreground; and by the repetition of this deer's orange hue in the ground,

which can be read as either behind or above the deer. Likewise, the largest

deer takes its blue color from what may be fractured intervals of sky above.

Marc subverted but did not efface the descriptive function of line and color.

Recognizable forms are framed within broken templates that both echo the

forms and distill them into an abstract geometry. Contours disintegrate and

reemerge within a restless grid that oscillates between opacity and transparency. The contrast between the brilliantly colored animal family and the

violence of the abstract scheme seems to suggest a transformative event.

Marc meant to place the viewer before a nature become porous, a nature

whose surfaces submit to a momentous transformation from within. What

Marc intended for the viewer to behold in Deer in the Forest II and so many

pictures like it at this time was an ontological revelation, a disclosure of what

underlay reality. In a reversal of the Hegelian subordination of art to philosophy as the ultimate disclosure of Geist, Marc looked to art to reveal meta-

physical laws which only philosophy had previously known (Marc 106).

Despite the importance of representational form in this visual dialectic in

Marc's late work, several writers have focused on a small number of canvases

of 1914 which they believe are completely non-objective.28 The painting

most often adduced as evidence of Marc's allegedly non-objective aim is

Struggling Forms (fig. 3). But as even a cursory examination of this painting

demonstrates, the attempt to portray Marc's final works as decisively nonrepresentational is unfounded. The large red shape on the left suggests the

form of a bird, perhaps an eagle, and the linear forms possess the character of

lashing talons or tendrils reminiscent of futurist lines of force describing

violent motion. It may be that the combat between mimetic and abstract

forms tips in favor of the latter in Struggling Forms; but when viewed in the

Weltanschauung from Weltdurchschauung, regarding the latter as symptomatic of the new

art which did not seek form "im Aussen, in der stilisierten Facade der Natur" but

constructed "von innen heraus."

28 John Moffitt, "Fighting Forms: The Fate of the Animals: The Occultist Origins of

Franz Marc's 'Farbentheorie,' " Artibus et Historiae, 12 (1985), 122, repr. in Kathleen J.

Regier (ed.), The Spiritual Image in Modern Art (Wheaton, Ill., 1987); Klaus Lankheit,

Franz Marc (Cologne, 1976), 130; Marc Rosenthal, "Franz Marc: Pioneer of Spiritual

Abstraction," in Franz Marc: 1880-1916 (Berkeley, 1979), 31.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

David Morgan

332

context of Marc's entire oeuvre, the painting refuses to relinquish ties with

the painter's favorite subjects. Indeed, the struggle we witness may be the

very struggle of the artist to gaze, as it were, upon the reality that he believed

was concealed beneath the "stylized facade of nature" (Marc 195, ?35).

No appearance, no form of idealized imitation could express the absolute

for Marc as it could for Schiller and Schopenhauer. Schein as abstracted from

phenomena was still an imposition of the human will according to Marc, still

an aesthetic based on mimesis. To Marc the work of art was not an elevation

above or purification of nature, not a realm of free play of the imagination, as

Schiller characterized it, but a site of violent revelation, a destruction of

appearances, whether phenomenal or idealized. In an article of 1913 that he

entitled "Toward a Critique of the Past" Marc collapsed all forms of

apperception into the "mortal structure of our mind" and proceeded to

describe the nature and function of art:

The yearning for immutable being, for liberation from the sensory

deceptions of our ephemeral life is the fundamental disposition of all

art. Its great aim is to dissolve the entire system of our incomplete

sensations, to manifest an unearthly being that lives behind everything, to break the mirror of life [in order] that we gaze into being.

(Marc 169)

To break the mirror meant to transcend the mediated relation with nature that

representational art offered, to surpass the structures of appearance constructed by apperception. Marc strove to envision this revelation in art, to

show the break-through as an antagonistic engagement of abstract and figura-

tive forms: phenomena giving way to a higher ontology. This epiphany swept

away all forms of mimesis by suggesting the imminence of pure being. The

artist could not represent this in itself but could allude to or anticipate it by

envisioning the destruction of the present order as the birth of something

new.

The Ideology of Enchantment

As we have seen, because he regarded empathy as anthropom

Marc sought to move beyond it as an inadequate form of enchantm

it offered only a projection of human categories, empathy could not

hidden face of reality. He may have been encouraged in his re

empathy by Nietzsche's critique of anthropomorphism. In a pessim

struck by Schopenhauer and treated by the neo-Kantian historian o

phy, F. A. Lange, Nietzsche had argued that all human knowle

result of anthropomorphic projection:

The sublimity of nature, all those impressions of grandeur, nobi

grace, beauty, goodness, austerity, power, and rapture that we r

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Enchantment of Art

333

in the experience of nature, history, and mankind are not immediate

feelings, but the aftermath of innumerable, deep-rooted errors-everything would appear cold and lifeless to us were it not for this long

schooling.29

On another occasion Nietzsche insisted that, "apart from our condition of

living in it, the world that we have not reduced to our being, our logic and our

psychological prejudgments, does not exist as a world 'in itself.' '30

Yet Marc must have drawn greater support from Schopenhauer's metaphysics of the will than from Nietzsche's post-Wagnerian demythologizing

of romantic metaphysics. The former offered an escape from anthropomor-

phic delusion while Nietzsche, in the words of one scholar, came to the

conclusion that "thought cannot transcend the human standpoint or escape

its anthropomorphic perspective."31 The Birth of Tragedy (1872) extolled the

Dionysian aesthetic experience of ecstatic mingling with the "mysterious

primordial unity" of the will behind the torment of phenomenal existence;32

but by 1878 Nietzsche repudiated his earlier infatuation or enchantment with

Wagner and Schopenhauer by arguing that the thing in itself, the will, was an

"all too human" projection. Rather than renounce the individual will in

himself and merge with this metaphysical reality through art, Nietzsche

affirmed this world. He satirized the Schopenhauerian-Wagnerian religion of

art with its prophetic seer-artist:

The belief in great, superior, fertile minds is not necessarily, yet very

often connected to the religious or half-religious superstition that

those minds are of superhuman origin and possess certain miraculous

capabilities.... They are credited with a direct view into the essence of

the world, as through a hole in the cloak of appearance, and thought

able, without the toil or rigor of science, thanks to this miraculous

seer's glance, to communicate something ultimate and decisive about

man and the world.33

29 Quoted in George J. Stack, Lange and Nietzsche (New York, 1983), 125.

30 Ibid., 131.

31 George J. Stack, "Nietzsche and Anthropomorphism," Critica: Revista Hispanoamericana de Filosofia, 12 (1980), 48. Julian Young argues persuasively that Nietzsche's

middle period (Human, All Too Human, 1878; The Gay Science, 1882-87) rejected the

previous interest in Schopenhauer but that by 1888, with the Twilight of the Idols, he

returned to Schopenhauer's view of art in important respects (Nietzsche's Philosophy of

Art). Thus, opposing Schopenhauer and Nietzsche in any strict sense may miss Marc's debt

to both authors. Depending on what he read by Nietzsche, Marc could have found

Schopenhauer and Nietzsche in accord with one another. Moreover, Nietzsche remained at

least somewhat ambivalent about the enchantment of music in Human, All Too Human (see

?153).

32 Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy or Hellenism or Pessimism, tr. Wm. A. Haussmann

(New York, 1964), 27.

33 Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human, 112-13 (?164).

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

334

David Morgan

Nietzsche developed a critique of enchantment which contrasts with the

metaphysical aim which Marc assigned art. Nietzsche proposed a perspectivalism that embraced anthropomorphism as the necessary condition of

human knowledge. "Relativity" was inescapable. The "world" was unavoidably a valuation from the perspective of "the preservation and enhancement of the power of a certain species of animal."34

In notes written at the front in 1915 Marc explicitly rejected such

"Relativitat" as "a thoroughly secondary thought and as philosophy a false

doctrine which only exhausted minds could invent in order to give the

appearance of wit to their failure of judgment" (Marc 185, ? 1). In contrast to

Nietzsche, Marc insisted on the dualism of essence and appearance and

charged the artist with the task of penetrating to the "essence of the world,"

what he regarded as the purpose of abstraction, affirming that "[e]ach thing

in the world has its form, its formula, which we cannot touch with our coarse

hands, but which we can embrace intuitively in the degree that we are

artistically gifted" (Marc 113; 185, ?1). Schopenhauer's philosophy provided a special place for art as revelatory and redemptive. For this reason

Marc relied on Schopenhauer's construction of a dualistic contrast between

the surface of appearances and the will as the metaphysical basis for artistic

experience as a disclosure of the transcendent. For Marc this power was

nothing less than soteriological. In a group of notes from 1912-13 he proclaimed that "Faith in art is wanting, we wish to raise it up," and, complaining of the adulteration of the concept of art, concluded that "only a single

way out remains: return the word art to its purity and lead the people back to

God instead of the golden calf" (Marc 113, 114). Two years later, in the

midst of the war, he announced that "The coming art ... is our religion, our

center of gravity, our truth" (Marc 196, ?35). If Nietzsche sought to dismantle the religion of art, Marc yearned to reinvigorate it.

In spite of his vigorous rejection of animals and nature as ugly, Marc

could also write during the war years with a nostalgia that revived in him a

romantic ethos of empathy. In a letter of 1915 to his wife Marc described

gardens that reminded him of his own in Bavaria, and confessed: "More than

ever I am still in love with flowers and leaves. When I look at them some

feeling of compassion is always present, a kind of secret understanding."35

he embraced abstraction and empathy alternately because each in its own way

could reveal for him the deeper laws that governed appearances. With the

arrival of World War I and the emergence of the German nation as an

eschatological force in creating a new European order, Marc had turned with

even greater rigor to empathy as a patriotic enchantment. Not only did

34 Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power, ed. Walter Kaufmann, tr. Kaufmann and R.

J. Hollingdale (New York, 1967), 305, ?567.

35 Marc, Briefe aus dem Feld, 66. letter of 13 April 1915: "Ich bin noch mehr als je in

die Blumen und Blatter verliebt. Ich seh sie jetzt so anders an, irgend ein Gefuhl von

Mitleid ist immer dabei, eine Art Mitwissertum...."

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Enchantment of Art

335

empathy identify him with the elusive reality of the German nation unveiling

itself in the war as the future of Europe, the aesthetic of empathy allowed him

to express a mystical identity with Germany in conscious contrast to France

and its culture.

Two weeks before joining the army in the summer of 1914, Marc

revealed in a letter to the painter August Macke a fervent patriotism which

dismissed Parisian avant-garde painting. Suddenly the old romantic metaphors of blood and soil and the familiar contrast of Roman and Teuton serve

as the foundation of his art. In the pressing context of German mobilization

for the imminent war, we encounter the traditional rhetoric of German

nationalism extending from Vater Jahn to Julius Langbehn:

I am a German and can only plow my own field. What do I care about

the painting of the Orphists? As beautiful as the French are, we say:

Romans we cannot be. We Germans are and remain born graphic

artists, illustrators as well as painters. (Worringer says this very

nicely in his introduction to "Old German Book Illustration.") You

know how I love the French, but I cannot make myself into a

Frenchman. I dig [schiirfen] into myself, only into myself, and seek

what lives within me, to represent the rhythm of my blood....36

On the eve of the war, convinced of the unprovoked aggression against

the fatherland, Marc, like millions of Germans, prepared for the conflict by

seeking to ground his art within himself and his national identity. In this light

we do well to consider an alternative reading of Struggling Forms (fig. 3),

which was completed only shortly before the outbreak of conflict in a

summer dominated by rumors of war. An emphasis on abstraction as disinte-

gration sees the painting as visualizing the destruction of mimesis; but the

suggestive forms, one of which appears to be an eagle, invite, under the

auspices of empathy, a reading which puts the imagery to political use: as a

totem of imperial Germany, the eagle engages an enemy in battle for its

existence. Rather than passing out of existence, the eagle invites the viewer's

empathic conjuring of a narrative in which the German mascot fights for

dominance.37

Yet it was abstraction that remained the primary strategy for enchantment

for Marc until his death. The enchantment of abstraction consisted of a spell

cast by the new art of dissolving nature's appearances in search of a novel

36 Letter to Macke, 12 July 1914, Briefiechsel (Cologne, 1964), 184. For further

discussion, see Pese, Franz Marc: Leben und Werk (Stuttgart, 1989), 129. Already in 1910,

in Form Problems of the Gothic (New York, 1922), 416, Worringer had argued that the

Germans were the "conditio sine qua non of the Gothic."

37 On the political significance of the eagle for Marc see Peter Klaus Schuster, "In

Search of Paradise Lost: Runge-Marc-Beuys," Keith Hartley, Henry Meyric Hughes,

Peter-Klaus Schuster, and William Vaughan (eds.), The Romantic Spirit in German Art

1790-1990 (London, 1994), 74.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

336

David Morgan

order of being. Abstraction represented a new dispensation which Marc's late

writings demonstrate the war helped to usher in. The ideological function of

abstraction amounted to its magical ability to bring about a spiritual regen-

eration of Europe under a German aegis. What remains is to show the

mechanics of this enchantment.

Marc and the Problem of Modernity

The ideological significance of abstraction for Marc was framed within

his understanding of moder cultural history in Europe. Marc premised his

artistic efforts on a repudiation of nineteenth-century art and technological

developments and on an abiding, characteristically Germanic suspicion of

modernity. In effect, what he sought to exclude through abstraction was a

mechanized, industrialized modernity and its foundations in the applied

sciences and an economy geared to proliferate the moder urban world.

This is made clear in a number of Marc's writings in the last two years of

his life. For instance, in the midst of the catastrophic upheaval viewed firsthand from the trenches of the First World War, Marc defined "das

Abstrakte" as "natural sight, as primary, intuitive vision." He contrasted

this to "das Sentimentale": the "hysterical sickness and reduction of our

spiritual capacity to see," which he explicitly linked to a "deeply ill France"

and proclaimed was the sensibility that the war came to purge from the

moder world.38 "Our European will to abstract form," he wrote feverishly,

"is indeed nothing other than our highly conscious, energetic retaliation and

conquering of the sentimental spirit."39 This recalls Friedrich Schiller's

distinction between the naive and sentimental in poetry, where the naive

denoted simplicity, closeness to nature, and directness of expression and the

sentimental exhibited greater conceptuality, artificiality, and a longing for

nature from which it was estranged.40 Such an allusion in regard to abstract

art suggests that what Marc sought was a purified vision, a way of seeing

restored to "primitive" simplicity and directness. The appearances which he

sought to strip away were the artistic and social conventions which concealed

a spiritual view of nature whose features he could only anticipate in his

paintings. He grafted to Schiller's romantic primitivism the colonial discourse of German expressionism, which associated purity with the tribal

cultures of Germany's colonies. In contrast to moder society, "early man"

38 Marc, Schriften, 210 (?89); see also ?6 and ?86 on the question of the purification

and the war; and Briefe aus dem Feld, 60; on the sentimental sickness of France, 210, ?86.

39 Marc, Schriften, 210, ?87: "Unser europaischer Wille zur abstrakten Form ist ja

nichts anderes als unsre hochst bewusste, thatenheisse Erwiderung und Ueberwindung des

sentimentalen Geistes."

40 Friedrich Schiller, "Ueber Naive und sentimentalische Dichtung" (first published

in Die Horen, 1795). Marc reversed Schiller's scheme, which had located the naive in the

irretrievable past.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Enchantment of Art

337

had still not encountered the sentimental illness because, as Marc insisted,

"he loved the Abstract."4'

Many concerns which occupied Marc and shaped his estimation of the

significance of art can be found among those who sought to define a spiritual

and cultural agenda for Germany on the basis of the mythical idea of the Volk.

This ideology has been carefully studied in a classic work by George Mosse,

who has identified several themes among proponents of the Germanic Volk

that were also present in Marc's art and writings: an emphasis on intuition,

instinct, and feeling over reason; a suspicion of technology and moder

industry; a mystical, pantheistic experience of the German landscape; a

rejection of moder urban life; and a substitution of cultural ideals for

political and social praxis.42 It is of course important to point out that these

similarities to Marc's thought should be balanced against several significant

dissimilarities: Marc shared nothing of the antisemitism or the ardent nationalism of the volkish ideology; he spoke enthusiastically of the importance of

non-German artists at a time when it was not popular to do so; and he

exhibited an enduring ambivalence toward the aesthetic of empathy that

formed the basis of the volkish, patriotic, neo-romantic experience of the

landscape.43 Marc was not a rabid nationalist, but a patriot who came to

equate Europe's future with what he believed was the manifest destiny of

Germany.

In the fall of 1914 Marc wrote a brief essay in which he took care to

distinguish himself from the "narrowness of heart and of national desire"

and sought to redirect the "German cultural spirit and national impulse"

toward a broader European scope. Yet he did not hesitate to assert that

Germany would be, as France had formerly been, the "heart of Europe." On

the role of the war in accomplishing this Marc differed from his friend and

colleague, Wassily Kandinsky, who left Germany appalled at the violent

prospect of war.44 But Marc had no misgivings: "Germanness," he pro-

41 Marc, Schriften, 210, ?87. See Joan Weinstein, book review, Art Bulletin, 75 (1993),

183-87; also Jill Lloyd, German Expressionism: Primitivism and Modernity (New Haven,

1991); and David Morgan, "Empathy and the Experience of 'Otherness' in Pechstein's

Depictions of Women: The Expressionist Search for Immediacy," The Smart Museum of

Art Bulletin, University of Chicago, 4 (1992-93), 12-22.

42 George Mosse, The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third

Reich (New York, 1964), see especially the first four chapters.

43 See for instance Adolf Lasson, who wrote in the patriotic speech mentioned above:

"Idealistische Vertiefung in den Gegenstand, das ist der Grundzug des deutschen Geistes;

das bestimmt vor allem sein Verhaltnis zur Natur. Alles tiefere lebendige Naturgefuihl ist

deutschen Ursprungs" (Lasson, "Deutsche Art and deutsche Bildung," speech of 25

September 1914, repr. in Deutsche Reden in schwerer Zeit [Berlin, 1914-17], 21). See also

Elizabeth Kriegelstein, "Vom landschaftlichen Erlebnis," Preussische Jahrbiicher, 157

(1914), esp. 6. Mosse has considered and carefully differentiated expressionism and the

ideology of the Volk, Crisis of German Ideology, 157, 186-87.

44 Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, Briefwechsel, ed. Klaus Lankheit (Munich,

1993), 263ff, on the significance of the war.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

338

David Morgan

claimed, "will rise over all boundaries after this war."45 Thus, it is important

to recognize that certain affinities with conservative German nationalism

situate Marc within a cultural milieu that illuminates his ideology without,

however, fully defining it, and-it is important to bear in mind-help explain

why his art later appealed to the Nazis.46 As one recent study of expressionism has pointed out, "modernism and volkish-conservatism were not rigidly

separate phenomena, but rather parallel developments within a particular

historical context."47

A discussion of Marc's view of culture and modernity will bring his

ideology of abstraction into focus. If there was a single theme which charac-

terized the optimism behind the positivist conception of science and the

technocratic hopes for moder technology in the industrial state in the

nineteenth century, it was the fundamental belief in progress. This grew out

of the ideology of the enlightenment with such thinkers as Saint-Simon who

communicated a belief in progress to his pupil, Auguste Comte, through

whom it attained a permanent place in the presuppositions of positivism.48

The operative premise was that nature could be controlled by science and

technology to provide a secure environment for human development. Nothing could be more disenchanting: symbolic influence over the universe was

replaced by physical, technological control. Romantics early in the century

and neo-Romantics at the end resented this view because to them it tended to

reduce the experience of nature to a materialist framework shorn of the

beloved sublimity, mystery, and divine presence, in short, the power of

enchantment. Furthermore, the new industrialism with its techniques of mass

production made the tradition of Handwerk or craftsmanship obsolete and

thereby threatened to leave behind the customs and folkways inherited from

the past and transmitted in the arts and crafts. The rural, nationalist sensibility

was imperiled by an urban, pragmatic, and cosmopolitan understanding of

moder society.

Marc polemically described "progress" as a moder "system of religion" with its own prophets, priests, and laity (Marc 122). This new religion

replaced the "inner, inherited, and organic abilities of people with external,

learned, mechanical abilities." The gullibility of "the people" for this

religion disturbed Marc but not as much as the agents of technological

transformation of whom he spoke in the impersonal "they" as he lamented

the insidious effects of modern technology and its machines:

45 Marc, "Im Fegfeuer des Krieges," in Schriften, 161: "Das Deutschtum wird nach

diesem Kriege iiber alle Grenzen schwillen."

46 See Stephanie Barron, "Degenerate Art": The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi

Germany (Los Angeles, 1991), 295.

47 Lloyd, German Expressionism, 110.

48 Donald D. Egbert, "The Idea of the 'Avant-Garde' in Art and Politics," American

Historical Review, 73 (1967), 339-66.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Enchantment of Art

339

[T]hey build railroads for the people ... in order to spare them

walking and bearing burdens. But in reality, to make them bodily

dependent {and wretched}. They invent the telephone, the highspeed press, and the like for the people in order to impair their

independent thinking. They build machines so that people might

forget their wonderful abilities in the arts and crafts and become

sufficiently crude and stupid for the religion of progress.49

On another occasion Marc proclaimed that the "genuine art" of his day

was incompatible with "our scientific and technical age" (Marc 111). He

went on to prophesy that the "time will come very soon when we will find all

of our technology and science immeasurably boring; we will altogether

abandon it, even forget it; we will have no time for it because we will deal in

spiritual goods" (ibid.). Marc's aim to revive "faith in art" to lead the people

away from the false god of the mass cult of progress lead him to announce a

prophetic warning: the grand "achievements" of science and technology

were a "dangerous, bloody toy" in the hands of the people and may very well

lead to a violent end (Marc 123). Marc's art stands in contrast to the

mechanized world which his ongoing jeremiad bemoaned. In the place of

industrialized urban society he focused on the animal and its place in nature.

Even after Marc began dismantling the empathy between viewer and image,

nature remained the locus of epiphany, the violent epicenter of metaphysical

truth on which humanity depended for its spiritual welfare.

The revelation of metaphysical truths by the new art of abstraction

prophesied a transformation in European culture. During the war Marc wrote

passionately of what he called the "high type," the "few" who were being

"steeled" through the sacrifice of the war to carry on the struggle against the

bonds of the past (Marc 169). Marc took the trouble to point out that he was

not referring to politicians or their efforts or to the masses, but to the "good

European" whom he hoped would emerge from the war ready to assume the

task of ushering in a new age. The thought is indebted to Nietzsche's concept

of the Uebermensch. "Now is the hour," Marc wrote, "in which all values

will be measured anew ..."-transvalued (umwertet), Nietzsche would have

said.

During the war Marc became an avid reader of Nietzsche whose theme of

destruction developed Marc's antebellum reflections on struggle into a full

blown apocalyptic purge that promised a new age rising from the ashes of the

war.50 For millennia, we read, humanity has longed to overcome nature, to

peer behind the world, to see the back of divinity. The new European would

be poised to do just that. The war for Marc was a watershed that left the

Europe of the past steeped in absurdity.

49 Marc, Schriften, 122-23 (brackets enclose original text which Marc crossed out).

50 Ibid., 170, 66. On Nietzsche's importance for expressionist art and thought, see

Pese, Franz Marc, 51-58; and Donald Gordon, Expressionism: Art and Idea (New Haven,

1987), 11-25, esp. 16-17 and 24, on Marc's and Nietzsche's glorification of destruction.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

David Morgan

340

We stand on the other side, we few, the young, whom the jaws of the

war have spat on the far shore like the grumbling Jonah. Let us go

forth, onward, without looking back.... The great war has refreshed

and freed us.51

The war was a spiritual, cultural conflict in Marc's view, one waged in paint

and ideas as well as cannon and mortar shells. Indeed, this struggle was not

preeminently a political or social reality for Marc, but a metaphysical one.

Mosse has discussed the ways in which, since early in the nineteenth century,

volkish thought in Germany tended to detach itself from real events in the

political arena in order to address what it felt was the superior reality of the

spiritual crisis of the German Volk. Marc followed this pattern, although he

never exhibited extreme German nationalism. He had read Nietzsche too

attentively for that and, like the cosmopolitan philosopher, looked for a

supranational European elite to command affairs.52 Yet Marc was a proud

German who fully anticipated a just victory for his nation. And the "high

type" he awaited was going to be German. "The coming type of European,"

he wrote from the front in 1915, "will be the German type," although he was

careful to add that this would not occur before the German had become "a

good European" (Marc 161).

Marc's characterization of the relationship between art and nature in a

rhetoric of antagonistic struggle could easily be mystified by modernist

historiography as a noble struggle of the avant-gardist against a backward

establishment.53 However, this would overlook the fact that he forged his

rhetoric in a period of unprecedented German militarization. In fact his

ideology was able to mask German militarism. Rather than address the

political issues of Germany's foreign policy and historic preparation for war,

Marc mythologized the conflict into a search for European rebirth under the

star of German leadership. In November of 1914 he wrote the following:

Politics stand in a very loose and secondary relationship to the

meaning and course of world history, always merely the mask and

not the spirit, administration not imagination.... No and a thousand

times no, we Germans are not fighting for a place in the sun.... The

war concerns more [than that]. Europe ails from a deep-rooted weak-

51 Marc, Schriften, 173. The war was perceived by many German soldiers as possessing a cleansing, purifying power for modem Europe, see Wilhelm Pfeiler's examination of

letters from the front in his War and the German Mind (New York, 1941), 70-72.

52 Cf. The Gay Science, ?257, ?377, ?357, and ?377 contra German nationalism and in

favor of the "good European."

53 Helen Boorman, "Rethinking the Expressionist Era: Wilhelmine Cultural Debates

and Prussian Elements in German Expressionism," The Oxford Art Journal, 9 (1986), 315, examines the historiographical packaging of expressionism as "escapist" and "revolutionary," and originating in "anxiety" and "crisis."

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Enchantment of Art

341

ness and longs to be healthy, thus it pursues a frightful path of blood.

(Marc 163)

Such was the cultural rather than formally political strategy for European

renewal. This was the way of enchantment, the magic of a cultural tradition

of yearning, an artistic incantation which summoned into being a longed-for

state that politics and economics could not finally be trusted to achieve. As

Schiller had argued, the aesthetic state must be attained before the political

one could become a reality. But Marc found himself in the midst of unprecedented conflagration and no doubt expected the new art and the new Europe

would share a violent birth. He admired the Nietzschean will to power as a

dire expression of the need for radical cultural transformation, as a purgatorial fire to cleanse Europe. But after the war, Marc was convinced, the will to

power would take a constructive turn and become the "will to form" in order

to build a new order to replace the destruction of the old one (Marc 193, ?26).

The form which would emerge among artists, which was even then taking

shape in early experiments in abstraction would, according to Marc, visualize

the truth of things rather than their surfaces. Marc charted a path between the

two philosophers whom he admired by transforming Nietzsche's will to

power and by dismissing Schopenhauer's pessimism. The "good European"

would create a vision of the absolute that was not anthropomorphic pace

Nietzsche and that offered a viable alternative to the void into which

Schopenhauer saw all things pass (Marc 197, ??40, 41).

As a cultural strategy of enchantment, abstraction consisted of destroying

a bankrupt materialist worldview just as the war would purge society of its

decadence. By violently perforating the outer shell of phenomena, abstract

painting promised to unveil the absolute. What Marc fashioned in his abstract

art was a practice of image-making that preserved the Germanic notion that

the fatherland's problems were spiritual in character, that nature remained the

site of revelation and national identity, and that a cultural rebirth, the

complete epiphany of a new age, summoned by the new art, would follow the

purgatory of the war. Gripped by the need to glimpse what was invisible, to

embrace what was transcendent, the artist-shaman cast a spell that bewitched

whoever shared his urgency. Abstraction and empathy were powerful means

of imaging a transcendence to venerate and pointing toward an invisible

reality to behold. Each performed the cultural work of evocation, an ideological operation that attempted to transfigure the world through the work of art.

Such was the aim of the spiritual in art as a form of cultural enchantment.

Valparaiso University.

This content downloaded from

202.119.44.64 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 02:54:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms