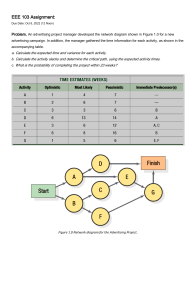

International Journal of Information Management 48 (2019) 96–107 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Information Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijinfomgt Exploring the psychological mechanisms from personalized advertisements to urge to buy impulsively on social media T ⁎ Virda Setyania, Yu-Qian Zhub, , Achmad Nizar Hidayantoa, Puspa Indahati Sandhyaduhitaa, Bo Hsiaoc a Faculty of Computer Science, University of Indonesia, Indonesia Department of Information Management, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Taiwan, ROC c Department of Information Management, Chang Jung Christian University, Taiwan, ROC b 1. Introduction Online impulse buying has become an epidemic as a result of advances in information technology and e-commerce. Considerable efforts have been devoted to identifying the factors that lead to impulse buying, and a multitude of antecedents were identified, such as user characteristics (e.g., hedonic needs and impulsiveness), online store characteristics (e.g., ease of use, interactivity), marketing stimuli (e.g., bonus and discounts), and product characteristics (e.g., type and price) (Chan, Cheung, & Lee, 2017). A systematic review of literature has found that most research has been focused on the general belief of the online store and user traits, while there is a lack of understanding of context-specific stimuli that trigger users’ online impulse buying behavior (Chan et al., 2017). Personalization is one of the technologies that create context-specific stimuli for users and is reportedly being used by online retailers to entice shopper's impulsive purchases (Dawson & Kim, 2010). Personalized advertisement incorporates information about the individual, such as demographic information, browsing history, and brand preferences (Bang & Wojdynski, 2016). With social media providing a continuous stream of data from billions of users about their likes and preferences, personalized advertisement has become the prevalent way for digital advertisers to communicate effectively with users (Chung, Wedel, & Rust, 2016), fueling the growth of social commerce. Personalized ads can increase click-through rates by as much as 670% relative to nonpersonalized advertisements (Beales, 2010; Summers, Smith, & Reczek, 2016), and has been considered as a key factor that contributes to user impulse buying (de Kervenoael, Aykac, & Palmer, 2009) Despite the impressive effectiveness of personalized advertisement in attracting people to click and buy on impulse, our knowledge about how this effectiveness is achieved is still limited. Prior research has reported that personalization increases advertising value and flow experience (Kim & Han, 2014), leads to favorable attitude (Xu, 2006), and receives higher attention (Köster, Rüth, Hamborg, & Kasper, 2015). Howard and Kerin (2004) discovered that users are more likely to have higher purchase intention for the product recommended in their personalized ads. However, prior research has not provided a coherent and integral account of how exactly personalized advertisement translates into click-through rates, and ultimately, urge to buy impulsively. The mechanism underlying the effectiveness of personalization in achieving higher click-through rates and impulse buying intentions remains, to a large degree, a black box to be opened. The present research tries to explore the psychological mechanisms and constructs underlying user's reactions to personalized advertisement on social media. Specifically, we examine how personalization increases the value of advertisement measured by perceived informativeness, credibility, creativity, and entertainment; we then look at how advertisement value translates into two click-through motivations: utilitarian click-through motivation and hedonic click-through motivation, which in turn, enhance impulsive buying intentions on social media. We contribute to extant literature with a more nuanced map of how personalization enhances click-through rates, thereby helping personalized advertiser to better understand, and strengthen their value to users. We also contribute to the impulsive buying literature by linking click-through motivations to impulsive buying intentions, which enhances our understanding how hedonic and utilitarian click-through motivations are related to impulsive buying intentions. With social commerce providing an environment even more conducive for impulsive buying (Xiang, Zheng, Lee, & Zhao, 2016), we enrich the social commerce literature by exploring how personalization, one of its technical environment elements, enhances impulsive buying intentions. In the next section, we begin with a discussion of the conceptual framework, and develop our hypotheses. We next describe our participants, data collection, and measures. The analysis and results are then presented, followed by a discussion of the results and conclusions. ⁎ Corresponding author at: Department of Information Management, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, No. 43, Keelung Road, Sec. 4, Da’an Dist., Taipei City 10607, Taiwan, ROC. E-mail addresses: setyani.virda@gmail.com (V. Setyani), yuqian@gmail.com (Y.-Q. Zhu), nizar@cs.ui.ac.id (A.N. Hidayanto), p.indahati@cs.ui.ac.id (P.I. Sandhyaduhita). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.01.007 Received 4 September 2017; Received in revised form 26 November 2018; Accepted 7 January 2019 Available online 23 February 2019 0268-4012/ © 2019 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. International Journal of Information Management 48 (2019) 96–107 V. Setyani, et al. 2. Conceptual framework and hypotheses sensation and novelty(hedonic) seeking. Voss, Spangenberg, and Grohmann (2003) further empirically tested and validated that hedonic motivations are related to affective attributes such as fun, exciting, delightful, enjoyable; and utilitarian motivations are related to cognitive attributes such as effective, helpful, practical and necessary. The theory was widely adopted in the IS and e-commerce literature and researchers have attributed informativeness, usefulness, cost-saving, credibility, convenience, selection to utilitarian motivation; and enjoyment, engagement, social, adventure and discovery to hedonic motivation to use IS services, buy online, or consume online content (Chiu, Wang, Fang, & Huang, 2014; Li & Mao, 2015; To, Liao, & Lin, 2007; Wang, Yeh, & Liao, 2013). Hedonic and utilitarian dimensions are ubiquitous in any consumption behavior and can provide building blocks for researchers attempting to develop models that explain a greater proportion of the variance in consumer behavior. They enable practitioners to test the effectiveness of advertising campaigns that stress experiential or functional strategies and reveal differences that may not be apparent when a single dimension measure is used (Voss et al., 2003). Integrating the advertising value and hedonic and utilitarian motivation theories, we build our research framework based on the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) Model (Mehrabian & Russell, 1974). The S-O-R model provides a systematic view of users’ behavior as a response to external stimuli, such as advertising, display or music (Bagozzi, 1986). The stimuli are external to the person and can consist of both marketing mix variables and other environmental inputs. In the S-O-R model, users respond to external stimulus with organism (O), which is the internal processes and structures consisting of perceptual, physiological, feeling, and thinking activities (Bagozzi, 1986). Organism intervenes between stimuli external to the person and the final actions, decisions, reactions, or responses, which is represented with R (response) (Bagozzi, 1986). In this study, the stimuli are personalized advertisements, while perceived advertising value and click-through motivation represent a two-stage internal process in organism. More specifically, we propose that personalized ads create value for users in the following dimensions: perceived informativeness, perceived credibility, perceived creativity, and perceived entertainment. We argue that these values created by personalized ads fuel users’ motivation to click through the advertisement and find out more about it on social media. Consistent with prior literature, cognitive values such as perceived informativeness and perceived credibility are linked to utilitarian click-through motivation, while affective or sensory values such as perceived creativity and perceived entertainment are linked to hedonic click-through motivation. Motivations to click through, in turn, lead to urge to buy impulsively. Our research model is depicted in Fig. 1. 2.1. Value of advertisement Based on the Uses and Gratifications Theory (UGT), Ducoffe (1996) developed a model that focused on advertising value, e.g. the subjective evaluation of the relative worth or utility of advertising to users, and explored what factors determine advertising value from a user's perspective. Predictors of advertising value can be categorized as either cognitive or affective (Ducoffe, 1996; Kim & Han, 2014). Cognitive factors include the perception of informativeness and credibility of the advertisement (Kim & Han, 2014). Informativeness refers to the ability to inform users of product alternatives for their greatest possible satisfaction (Gao & Koufaris, 2006). In advertising, there are three types of perceived credibility: the advertising message itself, the advertising site, and finally, the sponsor of the ad (Flanagin & Metzger, 2007). Ducoffe's model focuses on message credibility, which refers to the perceived truthfulness and believability of the advertising message (MacKenzie, Lutz, & Belch, 1986). Affective factors include perceptions of entertainment (Ducoffe, 1996; Kim & Han, 2014), which is positively related to advertisement value, and irritation, which is negatively related to advertisement value (Ducoffe, 1996). Entertainment denotes the ability to fulfill users’ needs for diversion, esthetic enjoyment or emotional release (McQuail, 2005), while irritation is the extent to which the advertising message is annoying and irritating to users (Kim & Han, 2014). Recently, creativity, which refers to the extent to which an ad is original and unexpected, is added as a new affective factor of advertising value (Lee & Hong, 2016; Reinartz & Saffert, 2013). These perceived values serve as perceptual antecedents that affect user attitude toward advertising (Ducoffe, 1996; Lee & Hong, 2016). Ducoffe's model has been extensively applied and modified in various research covering different contexts. Table 1 shows a brief summary of these studies. We integrate different studies and focused on four most commonly used advertising values in prior literature; namely, informativeness, credibility, entertainment and creativity. In the personalization context, one recent research reported the personalization is not significantly related to irritation (Kim & Han, 2014). In addition, irritation in the context of personalized ads was repeatedly found to be not significantly related to ad attitudes in various settings such as China, U.S. and Taiwan (Logan, Bright, & Gangadharbatla, 2012; Tsang, Ho, & Liang, 2004; Xu, 2006). Therefore, it is unlikely that irritation will be a significant mediator of personalization to urge to buy impulsively relationship in our context. Hence, we exclude irritation from the model to explore other more important constructs in the personalized ad context. 2.2. Hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumption 2.3. Personalized ads and advertisement value Hirschman (1980) argued that humans are endowed with two essential modes of consumption: thinking and sensing. He asserted that all consumption can be viewed as either cognition seeking (utilitarian) or How do personalized advertisements create value for users? We argue that it could create value for users in four different ways. First, as Table 1 Summary of Advertising values in prior literature. Source Context Results Xu (2006) Personalized ad in mobile advertising Perceived credibility and entertainment are positively related to ad attitude; informativeness and irritation are not significantly related to ad attitudes Logan et al. (2012) General social media advertising Perceived informativeness and entertainment are positively related to ad value; irritation is not significantly related to ad value Kim and Han (2014) Personalized ad in mobile advertising Perceived credibility, incentive and entertainment are positively related to ad value; irritation and informativeness are not significantly related to ad value Lee and Hong (2016) General social media advertising Perceived informativeness and creativity are positively related to attitude Tsang et al. (2004) General web advertising Perceived credibility and entertainment are positively related to ad attitude; informativeness and irritation are not significantly related to ad attitudes 97 International Journal of Information Management 48 (2019) 96–107 V. Setyani, et al. what is considered original, unexpected or meaningful, perceived creativity may well differ by factors such as user age, gender, education and culture (Smith & Yang, 2004). Instead of a general ad for all demographic groups, personalization allows advertisers to design content for each group, factor in the differenes between different groups (i.e., what would be considered “the usual” for a certain group) and thus come up with relevant and original content that is different from the pack and delivery it to the right audience. With high level of personalization, the advertisment content can be tailored to the target audience, thereby satisfying the need to be novel, different, and relevant for each group; accordingly, the messages will be perceived as more creative. Fig. 1. Proposed research model. H1c. Level of ad personalization is positively related to users’ perceived creativity. the internet content grows every day, users are typically overwhelmed by information and find it difficult to locate the exact piece of information that is useful to them. It is typical for a user to go through pages of search results before he/she finally finds the right piece of information. Gao and Koufaris (2006) found that users appreciate being given information that is important for making a purchasing decision. One of the main purposes of advertising is to distribute information of certain goods or services (Kim & Han, 2014), and personalized advertisements meet this purpose by tailoring the advertisement content according to user's personal information such as age, gender, preferences etc. Thus, it could provide more targeted and relevant information that meets user needs (Chen & Hsieh, 2012) and reduces information overload by channeling relevant information directly to individual users (Liang, Lai, & Ku, 2006). Information is valuable only when it is relevant and needed. Therefore, the higher the perceived personalization level of the advertisement, the higher the users’ perceive informativeness will be. Advertising entertainment lies in the ability to fulfill audience needs for diversion, esthetic enjoyment, or emotional release (McQuail, 2005). Like creativity, esthetics and tastes are very personal and differ greatly from person to person, and from group to group. With high level of personalization, the advertisments delievered are more appropriate for the audience, as the ads are tailored for their taste, preference and esthetics need. For example, cartoon characters may be perceived as quite entertaining and enjoyable by teenagers, but not so much by seniors. Accordingly, the higher the level of personalization, the more likely the messages will be perceived as entertaining. H1d. Level of ad personalization is positively related to users’ perceived entertainment. 2.4. Impact of advertising value on user's click-through motivation H1a. Level of ad personalization is positively related to users’ perceived informativeness. How does advertising value translate to users’ clicks? We try to link the values personalized advertisements create to two different types of click-through motivations: utilitarian and hedonic. In ecommerce, utilitarian motivation is linked with cognitive and functional factors such as convenience, information availability, product selection, efficiency, etc., while hedonic motivation seeks affective and sensory outcomes such as aesthetics, emotions, adventure, happiness, fantasy, awakening, sensuality, and enjoyment (To et al., 2007). Based on Mikalef, Giannakos, and Pateli (2013), we define utilitarian click-through motivation as the degree to which users perceive clicking-through personalized advertisements to browse further content to be a useful and effective means to find products or services, whereas hedonic clickthrough motivation is the degree to which users perceive clickingthrough personalized advertisements to browse further content to be a fun and emotionally stimulating experience. We argue that advertising values are positively related to both utilitarian and hedonic clickthrough motivations. Specifically, perceived informativeness and perceived credibility are cognition-based constructs and are related to utilitarian click-through motivation; while perceived entertainment and creativity are affection and experience-based constructs and are related to hedonic click-through motivation. First, personalized advertising provides tailored content based on users’ preferences, therefore increasing the availability of relevant information to users while at the same time reducing information overflow (Liang et al., 2006). The availability of product information is important for users, and is a key predictor of purchase intentions (Childers, Carr, Peck, & Carson, 2001). Prior research has found informativeness is positively related to utilitarian shopping motivation in ecommerce (Burke, 1997; To et al., 2007). When users perceive high informativeness from personalized advertisement (the ads are relevant, timely, and accurate), they are more likely to find clicking through the ads to be helpful and effective in satisfying their shopping needs. Therefore, we propose: Komiak and Benbasat (2006) argued that high level of personalization means that the advertisements users see effectively articulate the user's personal needs, and are consistent with the users’ personal shopping strategy. Highly personalized advertisment delivers better representation of user needs, generate more relevant and better-customized recommendations, and is more likely to be perceived as having high information quality and accuracy. Flanagin and Metzger (2007) argued that message credibility is determined by the accuracy and information quality of the message itself in the online environment. Hence, we infer that highly personalized ad can make users feel that the message in the personalized ad is more credible. Furthermore, personalization can serve as a cue for users, trigger cognitive heuristics about the nature of the underlying content, and shape user judgements of the content crediblity (Sundar, Kim, & Gambino, 2017). In particular, with high level of personalization, the similarity heuristic (if there is a similarity between my interest and what this ad offers, it is credible) and the helper heuristic (if this ad helps me find things I like, it is credible) are likely to be triggered, which enhance the perceived crediblity of the ad (Sundar et al., 2017). Therefore, we propose: H1b. Level of ad personalization is positively related to users’ perceived credibility. Advertising creativity is the extent to which an ad is original and unexpected (Haberland & Dacin, 1992). There has been a strong focus on creativity in advertising from both academia and industry as creativity has long been recognized as an important determinant of ad effectivenss (Smith & Yang, 2004). Divergence and relevance are important factors leading to creativity perceptions (Lee & Hong, 2016). Divergence is associated with being novel and different from the usual, while relevance is concerned with being meaningful, appropriate, useful, and valuable (Smith, MacKenzie, Yang, Buchholz, & Darley, 2007). As different demographics groups have different ideas about H2. Perceived informativeness is positively related to utilitarian click98 International Journal of Information Management 48 (2019) 96–107 V. Setyani, et al. central component in the unplanned buying process (Verhagen & van Dolen, 2011). Exposure to situational stimuli has been found to be a main driver of impulsive buying (Chan et al., 2017). Verhagen and van Dolen (2011) reported browsing activities lead to higher impulsive buying urges. When people click through the ads, regardless of utilitarian or hedonic motivation, they are likely to be exposed to more information about the product or service, more opportunities for not only exposure to extrinsic stimuli, but also positive affects, which all increase the urge to buy impulsively (Huang, 2015; Verhagen & van Dolen, 2011). Therefore, we propose: through motivation. Although there is ample information on social media, people tend to be more cautious and do not believe every piece of information blindly (Kang, Höllerer, & O’Donovan, 2015). Cognitive response theory suggests that when persuasive communications are perceived as more credible, both the cognitive responses and attitude toward the ad are more favorable (Petty, Cacioppo, & Schumann, 1983). Perceived credibility of the source can determine the next action to be undertaken by users, including the willingness in receiving further information (Li & Suh, 2015). Credibility can effectively reduce the situational complexity as users can focus on evaluating the product without worrying whether the product information is biased or untruthful. In this way, credibility increases the efficiency of exploring product/services via clickingthrough personalized ads, which is a key aspect of utilitarian motivation. When you are confident that you can believe the information you see, time and efforts are saved from checking and verifying the truthfulness of the information. Thus, when users think of the personalized advertisement as credible, they are more likely to click-through the advertisements. H6. Utilitarian click-through motivation is positively related to the urge to buy impulsively. H7. Hedonic click-through motivation is positively related to the urge to buy impulsively. 2.6. The mediation hypotheses Based on the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) Model, we propose a research model that systematically examines users’ response to personalized advertising. The S-O-R model is the most widely adopted framework in online impulsive buying research as it emphasizes the role of environmental cues in online impulse buying behavior and can be largely reconciled with research drawn on the environmental psychology paradigm (Chan et al., 2017). In our model, personalized advertising serves as the stimuli, perceived advertising value and clickthrough motivations serves as the organism between stimuli and the final responses of impulsive buying intentions. Ducoffe (1996) maintained that perceived values serve as perceptual antecedents that affect user attitude toward advertising. Thus, perceived advertising value is likely to influence people's attitude about the personalized ad on whether they would think it is helpful or fun to click through the link and learn more about it. Finally, the urge to buy impulsively represents the response component in our study. In essence, our model depicts the four advertising values and click-through motivations as the internal mechanisms that mediate the relationship between personalized ads and urge to buy impulsively. Therefore, we develop the following mediation hypotheses: H3. Perceived credibility is positively related to utilitarian clickthrough motivation. Hedonic motivation is associated with need for novelty, variety, and surprise (Hausman, 2000; Hirschman, 1980; Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982). Mehrabian and Russell (1974) suggest that novelty and unfamiliarity in the environment lead to arousal. Poels and Dewitte (2008) explored the question of how ad creativity can be characterized from an emotional point of view and found that creativity leads to pleasure and arousal reactions in consumers. Yang and Smith (2009) reasoned that processing creative ads should be deemed as intrinsically interesting and enjoyable because consumers have the internal dispositions to appreciate stimuli that is different and surprising. They found that creative ads lead to positive affects such as interested, excited, and inspired. Im, Bhat, and Lee (2015) found that novelty in ads is linked to perceived hedonic value of the ads. As creative content is novel, out-of-ordinary, intriguing and surprising (Lee & Hong, 2016), it is likely to arouse experiential or sensory reactions and satisfy the need for novelty, variety and surprises that correspond with hedonic-seeking consumers (Voss et al., 2003). Therefore, the higher the perceived creativity, the higher the users’ hedonic motivation to click through the ad in search of novelty, variety and surprise would be. H8a. Perceived informativeness and utilitarian click-through motivations mediate the relationship between level of ad personalization and urge to buy impulsively. H4. Perceived creativity is positively related to hedonic click-through motivation. H8b. Perceived credibility and utilitarian click-through motivations mediate the relationship between level of ad personalization and urge to buy impulsively. Another factor that attracts user attention is entertainment. Tsang et al. (2004) found that perceived entertainment is the biggest predictor of user's attitude toward the advertising message on their mobile phones. Enjoyment, fun, and entertainment reflect the hedonic aspects of user's motivation to use technologies (Weijters, Rangarajan, Falk, & Schillewaert, 2007). Ads with high entertainment value are exciting, enjoyable and fun (Ducoffe, 1996). As hedonic motivation seeks happiness, fantasy, awakening, sensuality, and enjoyment (To et al., 2007), high entertainment value is likely to increases hedonic motivation to click-through the ads to experience more and see more content. H8c. Perceived creativity and hedonic click-through motivations mediate the relationship between level of ad personalization and urge to buy impulsively. H8d. Perceived entertainment and hedonic click-through motivations mediate the relationship between level of ad personalization and urge to buy impulsively. As perceived advertising value and click-through motivations are the organism between stimuli and the final responses of impulsive buying intentions, we expect that they fully mediate the relationship between level of ad personalization and urge to buy impulsively. H5. Perceived entertainment is positively related to hedonic clickthrough motivation. H8e. Perceived advertising value and click-through motivations fully mediate the relationship between level of ad personalization and urge to buy impulsively. 2.5. User's click-through motivation and urge to buy impulsively When users click-through the ad in social media, they are linked to the product web site where they could browse and examine the product or service with more detailed information. Browsing, defined as the examination of a merchandize for recreational and informational purposes without an immediate intent to buy, has been argued to be a 99 International Journal of Information Management 48 (2019) 96–107 V. Setyani, et al. 3. Methodology strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Personalization items were adopted from Kim and Han (2014). Items for perceived entertainment, perceived informativeness, perceived creativity, and perceived credibility were adapted from Lee and Hong (2016), Kim and Han (2014), and Buil, Chernatony, and Martinez (2013). Utilitarian and hedonic click-through motivation items were from Mikalef et al. (2013). Finally, urge to buy impulsively measures were derived from Huang (2015), and Kacen and Lee (2002). Complete questionnaire items for each dimension can be found in Appendix. We controlled for age and shopping budget for shopping to partial out any possible confounding effects as suggested by prior research on impulsive buying (Jeffrey & Hodge, 2007; Stilley, Inman, & Wakefield, 2010) and independently tested gender's effect on our dependent variable. 3.1. Participants and procedure The target population of this study is social media users in Indonesia. With a population of 261 million, Indonesia is the world's fourth most populous country, largest Muslim population, and Southeast Asia's largest economy. Indonesia is considered as quite representative of developing countries, especially in the Asia Pacific region. Samples from Indonesia could possibly be generalized to other developing countries, especially those with similar cultural, political, techno-logical, legal and socioeconomic conditions (Kurnia, Karnali, & Rahim, 2015). We enlisted respondents that were familiar with social media advertising to ensure that they would able to answer the questions in the questionnaire. The initial screening questions excluded respondents that (1) did not have a social media account and (2) were not Indonesian to ensure that our sample was consistent with our population. In the beginning of the questionnaire, we gave them an example of social media advertising taken from a personalized Facebook advertising page and asked the respondents to login into their social media account and view social media advertising that has been personalized. The respondents then were asked to reflect upon their experience when viewing the ad and fill out the questionnaire. We distributed questionnaire online through various social media platforms and forums in Indonesia. The survey was administrated for approximately two months starting from March 24, 2016. Data from 963 respondents were collected, of which 101 were invalid or incomplete. Finally, 862 data points were used in our analysis. The distribution of respondent demographics is summarized in Table 2. There were more female respondents (72%) than male respondents (28%). Respondents aged between 21 and 25 year represented the majority of the samples (51%). Most respondents were seeing/reading advertising social media several times in a day 4. Results and analysis 4.1. Data normality, linearity and homoscedasticity Before conducting SEM analysis, we checked our data for normality, linearity and homoscedasticity (Hair, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2011). Hair et al. (2011) argued that to meet normality requirements, the skewness should be between −2 to +2 and kurtosis should be between −7 to +7. The data normality test showed that the skewness and kurtosis stats for all our measures are within the recommended range. Therefore, data normality requirement was satisfied. Linearity is checked by examining the correlation matrix. As we can see from Table 3, no correlation between any two constructs is greater than 0.8, satisfying the requirement for linearity (Katz, 2006). Finally, homoscedasticity requires that all dependent variables exhibit equal level of variance across the range of predictor variables. We ran the Levene's test of equality of error variances and all constructs had a significance higher than 0.05, indicating that the variability in our dependent variables are not significantly different from each other. With these results, we proceeded to data analysis. 4.2. Measurement model testing 3.2. Measurements Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using structural equation model (SEM) with AMOS 2. First, we performed the convergent validity testing for each indicator, and found that all indicators except one (P4) met the 0.6 factor loadings threshold (Kline, 1994). We deleted P4 due to low factor loading. Next, we evaluated the AVE value of each variable, and all variables met the requirement of AVE > 0.5 (Hair et al., 2011) as exhibited in Table 5. We also conducted discriminant validity test per Hair et al. (2011). Table 3 shows that the square roots of AVE are greater than the correlation between variables. Furthermore, the cross-loading values of this research model, as shown by Table 4, also met the requirement such that each indicator has the largest correlation to its construct variable (Barclay, Higgins, & Thompson, 1995). Reliability in the forms of Composite Reliability (CR) and Cronbach's Alpha (CA) for each variable exceeded 0.7 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2011). Lastly, we addressed the concern for common method variance with two tests. First, we performed Harman's one-factor test (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, 2012). All items were included in an unrotated principal components factor analysis. The analysis yielded ten factors with eigenvalue > 1.0, with the first factor explaining 34.89% of the total variance. Second, we conducted the Common Latent Factor test in AMOS (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). This technique was similar to the Harman's one-factor test; however, the research model's latent variables and their relationships were kept in this analysis. The common bias was estimated by using the square of the common factor of each path before standardization. The resulting value of the common latent factor is 0.45. The results of both tests were below the recommended threshold of 50% (Eichhorn, 2014), suggesting that common method variance is unlikely to confound the interpretations of results (Eichhorn, 2014; Podsakoff The questionnaire was developed using five-point Likert scale from Table 2 Respondent demographics. Demographic variables Frequency Percentage Gender Female Male 623 239 72 28 Age 15–20 years 21–25 years 26–30 years 31–40 years 41–50 years > 50 years 313 441 54 34 18 2 36 51 6 4 2 0.2 Occupation Student Government employees Private employees Entrepreneur The others 649 28 75 3 115 23 47 13 3 6 Social media usage Several times a day Once a day 1–2 times a week 3–5 times a week Seldom 703 91 18 36 14 81 11 2 4 2 Impulsive buying experience Never These several days A few weeks ago A few months ago More than a year 220 128 206 261 47 26 15 24 30 5 100 International Journal of Information Management 48 (2019) 96–107 V. Setyani, et al. Table 3 Correlation matrix. P PE PI PC PD UM HM UB Age Budget Mean STD P PE PI PC PD UM HM UB Age Budget 3.055 2.942 3.104 3.014 2.682 3.049 2.937 3.170 1.849 2.441 .859 .887 .698 .784 .763 .782 .895 .956 .887 .816 (.832) .355** .448** .310** .342** .258** .292** .237** .067* .171** (.846) .650** .667** .451** .541** .626** .469** (.009) .140** (.727) .621** .593** .569** .560** .435** .014 .134** (.784) .500** .583** .632** .484** (.036) .094** (.829) .469** .494** .369** (.006) .152** (.800) .729** .472** −.092** .159** (.871) .559** (.064) .133** (.847) −.142** .179** – .234** – Square root of AVE in bold on diagonals are Pearson correlation of constructs. * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). Table 4 Loading and cross loading. UB5 UB4 UB3 UB2 UB1 HM1 HM2 HM3 HM4 HM5 UM5 UM4 UM3 UM2 UM1 PE1 PE2 PE3 PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 PD3 PD2 PD1 PI5 PI4 PI3 PI2 PI1 P1 P2 P3 Table 5 Reliability and convergent validity measures. P PE PC PD PI HM UM UB Indicator Loading Variable AVE CR CA 0.115 0.130 0.133 0.121 0.124 0.245 0.261 0.259 0.262 0.261 0.216 0.249 0.264 0.286 0.269 0.308 0.337 0.321 0.262 0.243 0.299 0.313 0.261 0.304 0.244 0.336 0.355 0.348 0.375 0.379 0.839 0.939 0.680 0.329 0.372 0.382 0.348 0.356 0.558 0.592 0.588 0.596 0.594 0.390 0.449 0.476 0.516 0.485 0.804 0.880 0.837 0.539 0.499 0.690 0.647 0.366 0.426 0.479 0.546 0.545 0.487 0.526 0.531 0.321 0.284 0.260 0.341 0.386 0.396 0.360 0.369 0.594 0.630 0.626 0.635 0.632 0.440 0.506 0.537 0.582 0.547 0.615 0.648 0.640 0.705 0.653 0.804 0.843 0.410 0.478 0.532 0.588 0.550 0.486 0.524 0.529 0.312 0.251 0.253 0.269 0.304 0.313 0.284 0.291 0.400 0.425 0.422 0.427 0.425 0.310 0.357 0.378 0.410 0.385 0.369 0.404 0.384 0.363 0.336 0.482 0.434 0.798 0.929 0.745 0.393 0.415 0.504 0.440 0.444 0.274 0.252 0.222 0.313 0.355 0.364 0.331 0.339 0.500 0.531 0.528 0.535 0.532 0.417 0.481 0.510 0.553 0.519 0.579 0.633 0.624 0.506 0.468 0.599 0.583 0.480 0.559 0.571 0.654 0.690 0.677 0.731 0.738 0.431 0.363 0.349 0.437 0.495 0.508 0.462 0.474 0.837 0.889 0.883 0.895 0.891 0.594 0.559 0.593 0.643 0.604 0.536 0.575 0.558 0.500 0.463 0.593 0.599 0.381 0.444 0.468 0.471 0.454 0.405 0.437 0.441 0.246 0.206 0.199 0.366 0.414 0.425 0.386 0.396 0.662 0.644 0.639 0.648 0.645 0.671 0.772 0.819 0.888 0.834 0.468 0.512 0.499 0.462 0.428 0.549 0.541 0.369 0.430 0.457 0.511 0.430 0.435 0.455 0.459 0.270 0.208 0.219 0.778 0.880 0.904 0.822 0.842 0.479 0.500 0.496 0.503 0.501 0.351 0.363 0.385 0.417 0.392 0.340 0.368 0.356 0.309 0.286 0.504 0.368 0.276 0.321 0.348 0.306 0.292 0.275 0.295 0.297 0.124 0.101 0.100 P1 P2 P3 0.849 0.936 0.693 Personalization (P) 0.692 0.869 0.835 PI1 PI2 PI3 PI4 PI5 0.76 0.696 0.728 0.747 0.704 Informativeness (PI) 0.529 0.849 0.848 PD1 PD2 PD3 0.736 0.934 0.804 Credibility (PD) 0.687 0.867 0.862 PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 0.81 0.784 0.75 0.79 Creativity (PC) 0.614 0.864 0.864 PE1 PE2 PE3 0.803 0.888 0.844 Entertainment (PE) 0.715 0.883 0.881 UM1 UM2 UM3 UM4 UM5 0.827 0.886 0.826 0.767 0.68 Utilitarian motivation (UM) 0.64 0.898 0.902 HM1 HM2 HM3 HM4 HM5 0.848 0.881 0.878 0.884 0.863 Hedonic motivation (HM) 0.758 0.94 0.948 indices were good: CMIN/DF = 2.184 (CMIN = 1168.7; DF = 535; suggested value < 5); GFI = 0.948 (suggested value > 0.9); CFI = 0.971 (suggested value > 0.9); TLI = 0.966 (suggested value > 0.9); RMSEA = 0.037 (suggested value < 0.10), pClose = 1. The results of structural model testing are summarized in Table 6 and Fig. 2. Our results show that the level of personalization is positively related to all four advertising values, with perceived informativeness having the largest effect size (beta = 0.57, P < 0.01). The four advertising values positively relates to utilitarian and hedonic clickthrough motivations. Utilitarian and hedonic click-through motivations, in turn, contributes to urge to buy impulsively. We controlled for age and spending budget. Age is significantly negatively related to urge to buy impulsively (beta = −0.13), while budget is significantly positively related to urge to buy impulsively (beta = 0.10). We independently tested the effect of gender and it was not significantly related to our dependent variable. P: personalization; PE: perceived entertainment, PC: perceived creativity; PD: perceived credibility; PI: perceived informativeness; HM: hedonic click-through motivation; UM: utilitarian click-through motivation; UB: urge to buy impulsively. et al., 2012). The last step of measurement model testing is the goodness of fit (GOF) testing. The fitness indices we obtained indicate that our data fit the measurement model well: CMIN/DF = 3.518 (CMIN = 1643; DF = 467; suggested value < 5); GFI = 0.927 (suggested value > 0.9); CFI = 0.946 (suggested value > 0.9); TLI = 0.939 (suggested value > 0.9); RMSEA = 0.054 (suggested value < 0.10), pClose = 0.01. 4.3. Structural model testing We tested the structural model with AMOS. The structural model fit 101 International Journal of Information Management 48 (2019) 96–107 V. Setyani, et al. Table 6 Summary of results. Hypotheses H1a H1b H1c H1d H2 H3 H4 H5 H7 H6 Table 7 Mediation test results. Estimate S.E. C.R. P Result Support Support Support Support Support Support Support Support Support Support P → PI P → PD P → PC P → PE PI → UM PD → UM PC → HM PE → HM HM → UB UM → UB 0.568 0.392 0.4 0.412 0.609 0.14 0.489 0.295 0.43 0.161 0.036 0.034 0.038 0.041 0.07 0.051 0.068 0.062 0.052 0.056 13.048 9.387 9.76 10.2 10.245 3.274 8.395 5.048 8.849 3.381 *** Age Budget −0.126 0.098 0.029 0.032 −4.435 3.477 *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** Parameter Estimate SE Bootstrapping Bias-corrected 95% CI Indirect effect P → PI → UM P → PD → UM P → PE > HM P → PC → HM P → PI → UM → UB P → PD → UM → UB P → PE > HM → UB P → PC → HM → UB Direct effect P → UM P → HM P → UM → UB P → HM → UB P → UB Total effect P → UM P → HM P → UM → UB P → HM → UB P → UB *** *** Significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). Lower Upper P 0.334 0.053 0.130 0.210 0.063 0.010 0.059 0.096 0.045 0.021 0.039 0.041 0.023 0.005 0.019 0.022 0.256 0.013 0.053 0.145 0.022 0.002 0.024 0.061 0.435 0.095 0.204 0.307 0.116 0.023 0.099 0.149 0.000 0.008 0.006 0.000 0.002 0.006 0.006 0.000 −0.125 0.003 −0.024 0.001 0.081 0.047 0.037 0.013 0.017 0.037 −0.216 −0.066 −0.056 −0.031 0.010 −0.03 0.076 −0.005 0.035 0.156 0.008 0.936 0.006 0.933 0.027 0.262 0.343 0.050 0.156 0.287 0.045 0.045 0.018 0.028 0.046 0.177 0.256 0.018 0.107 0.199 0.355 0.436 0.091 0.219 0.381 0.000 0.000 0.002 0.000 0.000 P: personalization; PE: perceived entertainment, PC: perceived creativity; PD: perceived credibility; PI: perceived informativeness; HM: hedonic click-through motivation; UM: utilitarian click-through motivation; UB: urge to buy impulsively. Fig. 2. Results. we stratified our sample according to the general gender and age distribution of social media users’ profile in Indonesia (slightly more male than female users and 90% of users under the age of 34) (eMarketer, 2016) and randomly discarded respondents from the over-represented strata to achieve better sample representativeness. In the end, we discarded 539 respondents and ended up with a sample of 323 respondents that were balanced according to age and gender. Chi-square tests showed that our sample did not differ from the expected age and gender distribution. Table 8 below shows our stratified sample distribution. We re-estimated model fit, reliability and validity and every requirement was met. We then reran the analysis and the results are reported in Table 9 and Table 10. We used multiple group structural model to test whether there are differences between the full sample model and the stratified sample 4.4. Mediation testing We tested whether advertising value and click-through motivations mediate the relationship between personalization and urge to buy impulsively with an asymmetric bootstrap test of mediation using biascorrected confidence intervals for indirect effects (Hamby, Daniloski, & Brinberg, 2015; Zhao, Lynch, & Chen, 2010). To establish mediation, the only requirement is a significant indirect effect (Zhao et al., 2010). The results show that all four advertising values serve as mediators from personalization to utilitarian and hedonic click-through motivations. Perceived informativeness has the biggest indirect effect (beta = 0.33, SE = 0.045, p < 0.01), followed by perceived creativity (beta = 0.21, SE = 0.021, p < 0.01), perceived entertainment (beta = 0.13, SE = 0.039, p < 0.01), and perceived credibility (beta = 0.05, SE = 0.041, p < 0.01). The four advertising values together with utilitarian and hedonic click-through motivations serve as serial mediators from personalization to urge to buy impulsively. Perceived creativity and hedonic motivation have the biggest indirect effect size (beta = 0.096, SE = 0.022, p < 0.01), followed by perceived informativeness and utilitarian motivation (beta = 0.063, SE = 0.023, p < 0.01), perceived entertainment and hedonic motivation (beta = 0.059, SE = 0.019, p < 0.01), and perceived credibility and utilitarian motivation (beta = 0.01, SE = 0.005, p < 0.01). The results provide support for the proposed serial mediation model. Perceived advertising value and click-through motivations, however, did not fully mediate the relationship between level of ad personalization and urge to buy impulsively, as the direct effects from personalization to utilitarian motivation and urge to buy impulsively are still significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 8a, 8b, 8c, 8d received support, while Hypothesis 8e did not (Table 7). Table 8 Stratified sample demographics. Demographics 4.5. Stratified sample test Because our sample was biased toward female and young respondents, our results could possibly be biased. To address this concern, Frequency Percent Gender Male Female 167 156 51.7 48.3 Generationa ≤35 years > 35 280 43 86.7 13.3 Age 15–20 years 21–25 years 26–30 years 31–40 years 41–50 years > 50 years 91 151 27 34 18 2 28.2 46.7 8.4 10.5 5.6 .6 Occupation Student Government employees Private employees Entrepreneur other 190 27 57 12 37 58.8 8.4 17.6 3.7 11.5 a We estimated the number of people aged 31–35 to be 50% of the 31–40 age bracket. 102 International Journal of Information Management 48 (2019) 96–107 V. Setyani, et al. Hsieh, 2012) and reduce information overload (Liang et al., 2006), but also expand the value of personalization to include a broader spectrum of values such as perceived creativity, perceived entertainment and perceived credibility. Prior research that broadly discusses the impact of utilitarian and hedonic motivation on impulsive buying has mostly found hedonic motivation to be the main driver of impulsive buy (Amos, Holmes, & Keneson, 2014; Chan et al., 2017), while utilitarian motivation is found to reduce impulsive buying (Park, Kim, Funches, & Foxx, 2011). Like prior research, this research found that in the social platform personalized advertisement context, hedonic motivation is a stronger driver of impulsive buy behavior. In our results, however, utilitarian clickthrough motivation is also significantly associated with urge to buy impulsively. We speculate that with the advancements in user data analysis, personalized advertisements are able to reflect and address a user's deeper needs, the ones that even the user him/herself may not be aware of. For example, a busy mom may not have thought about whether she need to buy a set of award-winning math tutorials for her kids, but when she sees advertisement for it on Facebook, which obviously knows her identity as a mother of young children, she finds it could be useful and helpful for her kids and immediately buys it. Therefore, personalized advertisements based on user's interest, roles, and preferences may profoundly change the landscape of impulsive buying in that it uncovers user's hidden needs and desires even before the user becomes aware of it. The classic driver of impulsive buying, hedonic motivation, is still a significant driver of urge to buy impulsively in our study, however, its role may be complemented by utilitarian click-through motivation in the personalized advertisement context. For our control variables, age and budget effects on urge to buy impulsively were confirmed. The results are in-line with prior research (Amos et al., 2014; Wells, Parboteeah, & Valacich, 2011). People are more capable of regulating themselves from impulsive buying as they advance in age. People with more budget, however, are more prone to impulsive buying behaviors. Advertising values are key mediators of the personalization to clickthrough motivation relationship. Specifically, perceived entertainment and creativity fully mediate the personalization to hedonic clickthrough motivation relationship, while perceived credibility and informativeness partially mediate the personalization to utilitarian clickthrough motivation relationship. Interestingly, the direct effect of personalization to utilitarian click-through motivation turned out to be negative, signaling a suppression effect, i.e., when the direct and mediated effects of an independent variable on a dependent variable have opposite signs (Cheung & Lau, 2008). Similarly, the indirect effect from personalization to urge to buy impulsively mediated through utilitarian click-through motivation is also negative. We suspect that this may be due to the so-called “Personalization Privacy Paradox” that people may feel toward personalization: on the one hand, personalized services add value to customers and increase customer loyalty; on the other hand, people are concerned about their privacy as personalization requires collection of customer personal data (Awad & Krishnan, 2006). When consumers perceive privacy invasion, they form less favorable attitudes toward the ad, and are less likely to buy (Cases, Fournier, Dubois, & Tanner, 2010). It is possible that these love/hate relationship consumers have with personalization is manifested in the opposite signs of the direct and indirect relationships personalization has on utilitarian click-through motivation. Advertising values along with utilitarian and hedonic click-through motivations serve as serial mediators from personalization to urge to buy impulsively, accounting for the majority of the personalization to urge to buy impulsively relationship. However, they failed to fully mediate the relationship, as the direct effect from personalization to urge to buy impulsively remained significant. Just as Zhao et al. (2010) have observed, most mediation studies report “partial mediation” with a significant direct path that is rarely predicted or explained. Zhao et al. Table 9 Stratified sample hypothesis testing. Hypotheses H1a H1b H1c H1d H2 H3 H4 H5 H7 H6 P P P P PI PD PC PE HM UM Age Budget Estimate PI PD PC PE UM UM HM HM UB UB UB UB 0.492 0.357 0.368 0.377 0.6 0.196 0.446 0.396 0.443 0.173 −0.178 0.088 S.E. 0.062 0.058 0.065 0.071 0.086 0.072 0.108 0.096 0.081 0.093 0.035 0.048 C.R. P Result 7.251 5.25 5.502 5.851 7.388 3.124 4.786 4.246 5.668 2.249 −4.072 2.019 *** Supported Supported Supported Supported Supported Supported Supported Supported Supported Supported *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** ** *** ** ** Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). *** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). Table 10 Stratified sample mediation test results. Parameter Estimate SE Bootstrapping Bias-corrected 95% CI Indirect effect P → PI → UM P → PD → UM P → PE → HM P → PC → HM P → PI → UM → UB P → PD → UM → UB P → PE → HM → UB P → PC → HM → UB Direct effect P → UM P → HM P → UM → UB P → HM → UB P → UB Total effect P → UM P → HM P → UM → UB P → HM → UB P → UB Lower Upper P 0.288 0.068 0.168 0.185 0.060 0.014 0.078 0.085 0.068 0.032 0.094 0.103 0.035 0.010 0.045 0.052 0.182 0.014 0.029 0.069 0.002 0.001 0.021 0.031 0.451 0.142 0.307 0.406 0.137 0.048 0.154 0.215 0.000 0.019 0.036 0.000 0.047 0.036 0.025 0.000 −0.152 −0.049 −0.032 −0.023 0.172 0.068 0.052 0.024 0.025 0.058 −0.294 −0.155 −0.095 −0.079 0.065 −0.025 0.050 0.000 0.020 0.294 0.020 0.307 0.051 0.259 0.001 0.204 0.304 0.043 0.140 0.355 0.078 0.077 0.027 0.044 0.076 0.051 0.158 0.004 0.070 0.217 0.361 0.465 0.114 0.247 0.512 0.007 0.000 0.030 0.000 0.000 model (Deng & Yuan, 2015). Specifically, measurement weights, structural weights and structural covariance were used to estimate the differences between the two models. The results show that all three parameters: measurement weights, structural weights and structural covariance are invariant between the full sample and the stratified sample, suggesting that there are no statistically significant differences between the results of the two models. Thus, the results seem to be robust with the complete sample test. 5. Discussion and conclusion 5.1. Discussion With the increasing popularity of personalized advertising in social media, it is important to understand how personalized advertising works and how it is linked to purchase intentions. This research explores the psychological mechanism and constructs underlying user's reactions to personalized advertisement. Our results show that personalized advertisement has significant influence on all four aspects of advertising value. The results not only resonance with prior literature that views the key value of personalization to be providing more targeted and relevant information that could meet user needs (Chen & 103 International Journal of Information Management 48 (2019) 96–107 V. Setyani, et al. (2010) contented that this may be an indication that there is an omitted mediator. Reflecting upon our context, we postulate that it is possible that there are other mediators in the process that were not included in our model. Some possible omissions are the social value and social click-through motivations. Facebook and other social platforms have the “like” button and often display ads with a line explaining, so and so from your friend list have liked the product or service. Thus, personalized ads could help you to understand your friends better, by showing you what they like, and could possible trigger you to click-through the ads because you are curious to find out what they liked or why the liked it. 5.3. Practical implications The results of this study are meaningful for companies deploying personalized advertisements in social media in several ways. As people spend more and more time on social media, managers respond by devoting considerable more resources to promote their products and services on social media. However, what really works for personalized advertisement on social platforms? What motivates users to click, and what makes them want to buy immediately? We offer the following recommendations for managers wondering these questions. First, provide relevant and useful information. Of the four advertising value, informativeness is the strongest predictor of click motivation, followed by creativity and entertainment. The results provide some guidelines for managers hoping to boost their click-through rates on social media personalized ads. To be informative, ads need to provide accurate and relevant information. With social media data, it is easier than ever to identify what would be relevant for a user based on their social media activities. For example, for young people troubled with acne and posting on their Facebook complaining about acne, the ad could provide information like “8 out of 10 find salicylic acid to be effective for their acne” and promote their product with salicylic acid ingredient. For young mothers perplexed by their babies’ fussiness, ads for anti-colic bottle could say “air in the bottle makes babies fussy. Try our new product”, which not only showcases the product, but also explains why this product is effective to keep the users informed. Second, be creative. Creativity is the biggest driver for hedonic click through motivation, and bears the biggest indirect effect from personalization to impulsive buying on social media personalized ads. Therefore, it is important to incorporate some unexpected and new elements in ads to attract people to buy. Creative ads are surprising and out of ordinary. Depending on what is the norm in ads of similar products, creative ad content could work from the usual and achieve the surprising element by going different directions. For example, instead of using beautiful girls in cosmetics ads, some ads creatively showed a beautiful “girl” removing all “her” makeup and in the end, turned out to be a boy to highlight the beauty product's transformative power. Third, keep them entertained. Entertainment bears the second largest indirect effect from personalization to impulsive buying. Therefore, it is helpful for the ads to be interesting and enjoyable. Depending on the user's interest and preferences, customized content could be applied. For example, Sci-Fi lovers would probably find an ad with Sci-Fi elements in it to be interesting, while sports fans would enjoy an ad with their favorite stars in it. Finally, motivate them. Hedonic and utilitarian click-through motivations both lead to higher impulsive buying urges, with hedonic motivation having a stronger effect size. Are there other ways to appeal to the hedonic side of motivation besides creativity and entertainment? How about aesthetics, adventure, happiness, fantasy or awakening (To et al., 2007)? Are there other ways to increase the utilitarian motivation of users besides credibility and informativeness? How about convenience, product selection and efficiency (To et al., 2007)? Personalization technology can be used to achieve these values. For example, if a person likes content about African safari adventures, an African safari ad would address the adventure side of hedonic motivation and is more likely to be clicked and viewed. The value of personalization lies in that it allows a multi-faceted understanding of the customer, and this understanding can be used to create customer value in different dimensions. Therefore, advertising value is not limited to the four that we examined in this research, but could be expanded to include more dimensions that correspond to either hedonic or utilitarian motivation of customer consumption. 5.2. Theoretical implications The effectiveness of personalized advertising has been widely recognized, what is less understood is how personalized advertising achieves these outcomes, necessitating the need to study the underlying mechanism. The promise of mediation analysis is that it can identify fundamental processes underlying human behavior that are relevant across behaviors and contexts, and enable us to develop efficient and powerful interventions to focus on variables in the mediating process (MacKinnon & Fairchild, 2009). Our research contributes to extant literature in three ways. First, our results uncovered the mechanism from personalized advertising to click-through motivation, explaining how personalized advertising lead to impressively higher click-through rates. This research proposed, and tested advertising values as mediators to two kinds of click motivation. Our results show that there could be multiple paths for personalized advertisement to exert its effect on click-through rates. It could be through providing valued information, enhancing advertiser's credibility, and providing tailored creative and entertaining content. By integrating click-through motivations and the advertising value framework, we unveiled the mediators that tie personalization to click-through motivation. The results not only contribute to extant literature with a better understanding of the process through which personalization works, but also aid managers in tailoring their efforts to further enhance personalizing effectiveness with four avenues of possible intervention, thereby helping personalized advertiser to better understand, and strengthen their value to users. Second, while prior research has examined impulsive shopping motivations from various lenses (Amos et al., 2014; Chan et al., 2017), few have investigated impulsive buying from a personalization perspective. Exposure to generic online advertisement in various formats (text, video and image) has been linked to impulsive buying (Adelaar, Chang, Lancendorfer, Lee, & Morimoto, 2003), yet little is known about the role of personalized advertisements in impulsive buying online. While 48% users reportedly spend more with personalized e-commerce (Fletcher, 2012), a theoretical account for the relationship between personalized advertising and impulsive buying is still missing. Based on the S-O-R model, this research contributes to the impulsive buying literature by theoretically linking personalized advertisement to impulsive buying intentions and explaining the process with advertising value and click-through motivations as the mediators. The findings enriched the S-O-R model with the two-stage internal process in organism and provided evidence for the importance of click-through rates in impulsive buying intentions. Third, our study adds new insights to the role of hedonic and utilitarian clicking in the personalized advertisement context. Contrary to prior research that identified utilitarian motivation as an inhibitor of impulsive buying (Park et al., 2011), this research found that in the social platform personalized advertisement context, utilitarian motivation also appears to be a driver of impulsive buying behavior. This may be partly due to the ability of data analytics and personalization to uncover users’ hidden needs and desires. This finding helps us to better understand how personalized advertisement transforms user's reaction in the social media platform and provide novel insights into buying intentions subsequent to user's social media clicking activities. 5.4. Limitations and future research Several limitations of this research should be noted. Although these findings are interesting, we relied mainly on cross-sectional self104 International Journal of Information Management 48 (2019) 96–107 V. Setyani, et al. social media platforms from different cultural background for personalized advertisement to achieve wider generalizability. Finally, we did not explore the relationship between utilitarian motivation and hedonic motivation, which could be a possible avenue for future research. reported conventional sample and only measured the intentions to buy impulsively. Future research could consider using actual sales numbers with a longitudinal design to validate the causal relationship between personalized advertisements and impulsive buying behavior. Second, similar to other online impulsive buying literature (Lo, Lin, & Hsu, 2016; Verhagen & van Dolen, 2011), our sample is biased toward women and young people. We accounted for this bias by stratifying our sample according to our population parameters and compare their differences. Third, we drew our sample from a single country. Thus, the generalizability of our results may be limited in countries with different cultural backgrounds. Future research could design tests with multiple Acknowledgements Yu-Qian Zhu is grateful for the support from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, ROC (Republic of China) (Funding #: 1052410-H-011-MY2). Appendix A. Measurement items Respondents were asked to respond to each statement by clicking the number that best indicated how strongly they agreed or disagreed with each statement. Five-point Likert scale was used, where 1 denoted Strongly Disagree, 2 denoted Disagree, 3 denoted Neutral, 4 denoted Agree, and 5 denoted Strongly Agree. Variable Code Items Personalization P1 P2 P3 P4 I feel that I feel that I feel that I feel that loading) Perceived Entertainment PE1 PE2 PE3 I feel that the ad on my social media is interesting I feel that the ad on my social media is enjoyable I feel that the ad on my social media is pleasant Kim and Han (2014) Perceived Informativeness PI1 PI2 PI3 PI4 PI5 The The The The The ad ad ad ad ad on on on on on my my my my my social social social social social media media media media media supplies relevant information on products or services provides timely information on products or services provides accurate product information is a good source of information is a good source of up to date products or services Hsu, Wang, Chih, and Lin (2015) and Kim and Han (2014) Perceived Creativity PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 The The The The ad ad ad ad on on on on my my my my social social social social media media media media is is is is Lee & Hong (2016) Perceived Credibility PD1 PD2 PD3 I feel that the ad on my social media is convincing I feel that the ad on my social media is believable I feel that the ad on my social media is credible Utilitarian click-through motivation UM1 Clicking through services) Clicking through services) Clicking through services) Clicking through services) Clicking through services) UM2 UM3 UM4 UM5 Hedonic click-through motivation Urge to Buy Impulsively HM1 HM2 HM3 HM4 HM5 UB1 UB2 UB3 UB4 UB5 Source the ad on my social media is tailored to me contents of the ad on my social media are personalized the ad on my social media is personalized for my use the ad on my social media is delivered in a timely way (deleted due to low factor unique really out of ordinary intriguing surprising Kim and Han (2014) Kim & Han (2014) the ad to browse products on my social media is effective (to find product/ Mikalef et al. (2013) the ad to browse products on my social media is helpful (to find product/ the ad to browse products on my social media is functional(to find product/ the ad to browse products on my social media is practical (to find product/ the ad to browse products on my social media is necessary (to find product/ Clicking through the ad to browse products on my social media is fun Mikalef et al. (2013) Clicking through the ad to browse products on my social media is exciting Clicking through the ad to browse products on my social media is delightful Clicking through the ad to browse products on my social media is enjoyable Clicking through the ad to browse products on my social media is thrilling I experienced a number a number of sudden urges to buy things after viewing the ad on my Huang (2015) social media I saw a number of things on the ad on my social media I wanted to buy even though they were not on my shopping list I felt a sudden urge to buy something after viewing the ad on my social media I want to buy things in the ad on my social media even though I had not planned to purchase I want to buy things in the ad on my social media even though I do not really need it buying. Journal of Retailing and User Services, 21(2), 86–97. Awad, N. F., & Krishnan, M. S. (2006). The personalization privacy paradox: An empirical evaluation of information transparency and the willingness to be profiled online for personalization. MIS Quarterly, 13–28. Bagozzi, R. P. (1986). Principles of marketing management. Chicago: Science Research Associates, Inc. Bang, H., & Wojdynski, B. W. (2016). Tracking users’ visual attention and responses to References Adelaar, T., Chang, S., Lancendorfer, K. M., Lee, B., & Morimoto, M. (2003). Effects of media formats on emotions and impulse buying intent. Journal of Information Technology, 18(4), 247–266. Amos, C., Holmes, G. R., & Keneson, W. C. (2014). A meta-analysis of user impulse 105 International Journal of Information Management 48 (2019) 96–107 V. Setyani, et al. Katz, M. H. (2006). Multivariable analysis: A practical guide for clinicians (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kim, Y. J., & Han, J. (2014). Why smartphone advertising attracts users: A model of web advertising, flow, and personalization. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 256–269. Kline, P. (1994). An easy guide to factor analysis. New York: Routledge. Köster, M., Rüth, M., Hamborg, C., & Kasper, K. (2015). Effects of personalized banner ads on visual attention and recognition memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 29(2), 181–192. Komiak, S. Y., & Benbasat, I. (2006). The effects of personalization and familiarity on trust and adoption of recommendation agents. MIS Quarterly, 30(4), 941–960. Kurnia, S., Karnali, R. J., & Rahim, M. M. (2015). A qualitative study of business-tobusiness electronic commerce adoption within the Indonesian grocery industry: A multi-theory perspective. Information & Management, 52(4), 518–536. Lee, J., & Hong, I. (2016). Predicting positive user responses to social media advertising: The roles of emotional appeal, informativeness, and creativity. International Journal of Information Management, 36(3), 360–373. Li, M., & Mao, J. (2015). Hedonic or utilitarian? Exploring the impact of communication style alignment on user's perception of virtual health advisory services. International Journal of Information Management, 35(2), 229–243. Li, R., & Suh, A. (2015). Factors influencing information credibility on social media platforms: Evidence from Facebook pages. Procedia Computer Science, 72, 314–328. Liang, T.-P., Lai, H.-J., & Ku, Y.-C. (2006). Personalized content recommendation and user satisfaction: Theoretical synthesis and empirical findings. Journal of Management Information Systems, 23(3), 45–70. Lo, L. Y. S., Lin, S. W., & Hsu, L. Y. (2016). Motivation for online impulse buying: A twofactor theory perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 36(5), 759–772. Logan, K., Bright, L. F., & Gangadharbatla, H. (2012). Facebook versus television: Advertising value perceptions among females. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 6(3), 164–179. MacKenzie, S. B., Lutz, R. J., & Belch, G. E. (1986). The role of attitude toward the ad as a mediator of advertising effectiveness: A test of competing explanations. Journal of Marketing Research, 23(2), 130–143. MacKinnon, D. P., & Fairchild, A. J. (2009). Current directions in mediation analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(1), 16–20. McQuail, D. (2005). Mass communication theory (5th ed.). London: Sage Publications. Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Mikalef, P., Giannakos, M., & Pateli, A. (2013). Shopping and word-of-mouth intentions on social media. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 8(1), 17–34. Park, E. J., Kim, E. Y., Funches, V. M., & Foxx, W. (2011). Apparel product attributes, web browsing, and e-impulse buying on shopping websites. Journal of Business Research, 65(11), 1583–1589. Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Schumann, D. (1983). Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement. Journal of User Research, 10(2), 135–146. Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903. Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. Poels, K., & Dewitte, S. (2008). Getting a line on print ads: Pleasure and arousal reactions reveal an implicit advertising mechanism. Journal of Advertising, 37(4), 63–74. Reinartz, W., & Saffert, P. (2013). Creativity in advertising: When it works and when it doesn’t. Harvard Business Review, 91(6), 106–112. Smith, R. E., MacKenzie, S. B., Yang, X., Buchholz, L. M., & Darley, W. K. (2007). Modeling the determinants and effects of creativity in advertising. Marketing Science, 26(6), 819–833. Smith, R. E., & Yang, X. (2004). Toward a general theory of creativity in advertising: Examining the role of divergence. Marketing Theory, 4(1–2), 31–58. Stilley, K. M., Inman, J. J., & Wakefield, K. L. (2010). Spending on the fly: Mental budgets, promotions, and spending behavior. Journal of Marketing, 74(3), 34–47. Summers, C. A., Smith, R. W., & Reczek, R. W. (2016). An audience of one: Behaviorally targeted ads as implied social labels. Journal of User Research, 43(1), 156–178. Sundar, S. S., Kim, J., & Gambino, A. (2017). Using theory of interactive media effects (TIME) to analyze digital advertisingDigital advertising: Theory and research (3rd ed.). Taylor and Francis86–109. To, P. L., Liao, C., & Lin, T. H. (2007). Shopping motivations on Internet: A study based on utilitarian and hedonic value. Technovation, 27(12), 774–787. Tsang, M. M., Ho, S. C., & Liang, T. P. (2004). User attitudes toward mobile advertising: An empirical study. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 8(3), 65–78. Verhagen, T., & van Dolen, W. (2011). The influence of online store beliefs on user online impulse buying: A model and empirical application. Information & Management, 48(8), 320–327. Voss, K. E., Spangenberg, E. R., & Grohmann, B. (2003). Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitude. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(3), 310–320. Wang, Y. S., Yeh, C. H., & Liao, Y. W. (2013). What drives purchase intention in the context of online content services? The moderating role of ethical self-efficacy for online piracy. International Journal of Information Management, 33(1), 199–208. Weijters, B., Rangarajan, D., Falk, T., & Schillewaert, N. (2007). Determinants and outcomes of user's use of self-service technology in a retail setting. Journal of Service Research, 10(1), 3–21. Wells, J., Parboteeah, D., & Valacich, J. (2011). Online impulse buying: Understanding personalized advertising based on task cognitive demand. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 867–876. Barclay, D., Higgins, C., & Thompson, R. (1995). The partial least squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as illustration. Technology Studies, 2(22), 285–309. Beales, H. (2010). The value of behavioral targeting. Network Advertising Initiative (NAI). Retrieved from http://www.networkadvertising.org/pdfs/Beales_NAI_Study.pdf. Buil, I., Chernatony, L.d., & Martinez, E. (2013). Examining the role of advertising and sales promotions in brand equity creation. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 115–122. Burke, R. R. (1997). Do you see what I see? The future of virtual shopping. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(4), 352–361. Cases, A. S., Fournier, C., Dubois, P. L., & Tanner, J. F., Jr. (2010). Web Site spill over to email campaigns: The role of privacy, trust and shoppers’ attitudes. Journal of Business Research, 63(9–10), 993–999. Chan, T. K., Cheung, C. M., & Lee, Z. W. (2017). The state of online impulse-buying research: A literature analysis. Information & Management, 54(2), 204–217. Chen, P. T., & Hsieh, H. P. (2012). Personalized mobile advertising: Its key attributes, trends, and social impact. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 79(3), 543–557. Cheung, G. W., & Lau, R. S. (2008). Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods, 11(2), 296–325. Childers, T. L., Carr, C. L., Peck, J., & Carson, S. (2001). Hedonic and utilitarian motivations for online retail shopping behavior. Journal of Retailing, 77(4), 511–535. Chiu, C. M., Wang, E. T., Fang, Y. H., & Huang, H. Y. (2014). Understanding customers’ repeat purchase intentions in B2C e-commerce: The roles of utilitarian value, hedonic value and perceived risk. Information Systems Journal, 24(1), 85–114. Chung, T. S., Wedel, M., & Rust, R. T. (2016). Adaptive personalization using social networks. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(1), 66–87. Dawson, S., & Kim, M. (2010). Cues on apparel web sites that trigger impulse purchases. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 14(2), 230–246. de Kervenoael, R., Aykac, D. S. O., & Palmer, M. (2009). Online social capital: Understanding e-impulse buying in practice. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 16(4), 320–328. Deng, L., & Yuan, K. H. (2015). Multiple-group analysis for structural equation modeling with dependent samples. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 22(4), 552–567. Ducoffe, R. (1996). Advertising value and advertising on the web. Journal of Advertising Research, 36(5), 21–34. Eichhorn, B. R. (2014). Common method variance techniques. MWSUG 2014 Proceedings. Midwest SAS Users Group 2014 Proceedings Paper AA-11. eMarketer. (2016). Demographic profile of social network users in Indonesia, July 2015–June 2016. Retrieved from http://www.eMarketer.com/ (Accessed 21 May 2017). Flanagin, A. J., & Metzger, M. J. (2007). The role of site features, user attributes, and information verification behaviors on the perceived credibility of web-based information. New Media & Society, 9(2), 319–342. Fletcher, H. (2012). 48% of users spend more after personalized e-commerce efforts, survey says. Retrieved from http://www.targetmarketingmag.com/article/48-users-spendmore-after-personalized-e-commerce-efforts-survey/all/ (Accessed 21 May 2017). Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50. Gao, Y., & Koufaris, M. (2006). Perceptual antecedents of user attitude in electronic commerce. ACM SIGMIS Database: The DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 37(2–3), 42–50. Haberland, G. S., & Dacin, P. A. (1992). The development of a measure to assess viewers’ judgments of the creativity of an advertisement: A preliminary study. Advances in User Research, 19, 817–825. Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–151. Hamby, A., Daniloski, K., & Brinberg, D. (2015). How consumer reviews persuade through narratives. Journal of Business Research, 68(6), 1242–1250. Hausman, A. (2000). A multi-method investigation of consumer motivations in impulse buying behavior. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 17(5), 403–426. Hirschman, E. C. (1980). Innovativeness, novelty seeking, and consumer creativity. Journal of Consumer Research, 7(3), 283–295. Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132–140. Howard, D. J., & Kerin, R. A. (2004). The effects of personalized product recommendations on advertisement response rates: The “try this. It works!” technique. Journal of User Psychology, 14(3), 271–279. Hsu, L. C., Wang, K. Y., Chih, W. H., & Lin, K. Y. (2015). Investigating the ripple effect in virtual communities: An example of Facebook Fan Pages. Computers in Human Behavior, 51(A), 483–494. Huang, L. T. (2015). Flow and social capital theory in online impulse buying. Journal of Business Research, 69(6), 2277–2283. Im, S., Bhat, S., & Lee, Y. (2015). Consumer perceptions of product creativity, coolness, value and attitude. Journal of Business Research, 68(1), 166–172. Jeffrey, S. A., & Hodge, R. (2007). Factors influencing impulse buying during an online purchase. Electronic Commerce Research, 7(3–4), 367–379. Kacen, J. J., & Lee, J. A. (2002). The influence of culture on user impulsive buying behavior. Journal of User Psychology, 12(2), 163–176. Kang, B., Höllerer, T., & O’Donovan, J. (2015). Believe it or not? Analyzing information credibility in microblogs. Poster session presentation at International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining. 106 International Journal of Information Management 48 (2019) 96–107 V. Setyani, et al. Puspa Indahati Sandhyaduhita is currently a lecturer at the Faculty of Computer Science, Universitas Indonesia. She received her master degree in Computer Science, Information Architecture Track from TU Delft, the Netherlands. Her research interests include information systems, IS requirements, business process modeling, enterprise architecture, enterprise resource planning, IS adoption, e-commerce, e-government and knowledge management systems. Her researches have been published in International Journal of E-health and Medical Communications, Information Resources Management Journal, International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development, Electronic Government and other international refereed journals and conference proceedings the interplay between user impulsiveness and website quality. Journal of the Association of Information Systems, 12(1), 32–56. Xiang, L., Zheng, X., Lee, M. K., & Zhao, D. (2016). Exploring users’ impulse buying behavior on social commerce platform: The role of parasocial interaction. International Journal of Information Management, 36(3), 333–347. Xu, D. J. (2006). The influence of personalization in affecting user attitudes toward mobile advertising in China. The Journal of Computer Information Systems, 47(2), 9–19. Yang, X., & Smith, R. E. (2009). Beyond attention effects: Modeling the persuasive and emotional effects of advertising creativity. Marketing Science, 28(5), 935–949. Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., Jr., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. Virda Setyani is currently a developer in one of the biggest Indonesian e-marketplace and part-time teaching assistant at Faculty of Computer Science, Universitas Indonesia. She received her bachelor's degree from Department of Information Systems, Universitas Indonesia. Her research interests are mainly in e-commerce, business intelligence, and social media. Bo Hsiao is an Associate Professor in the Department of Information Management at Chang Jung Christian University, Taiwan. He received his PhD degree in Information Management from National Taiwan University, Taiwan. His research interests include manufacturing information systems, data envelopment analysis, project management, knowledge economy, and pattern recognition. Yu-Qian Zhu is Associate Professor in the Department of Information Management, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology. She holds a PhD in Management of Technology from National Taiwan University. Prior to her academic career, she served as R&D engineer and R&D manager in Fortune 100 and InfoTech 100 firms. Her research interests include knowledge management, R&D team management, and social media. Her works can be found in journals such as Journal of Management, R&D Management, International Journal of Information Management, Government Information Quarterly, Computers in Human Behavior etc. YuQian can be contacted at yzhu@mail.ntust.edu.tw Achmad Nizar Hidayanto is an Associate Professor and the Head of Information Systems/Information Technology Stream, the Faculty of Computer Science, Universitas Indonesia. He received his PhD in Computer Science from Universitas Indonesia. His research interests are information systems/information technology adoption, e-commerce, e-government, social media analysis, knowledge management, and strategic information technology management. Her researches have been published in International Journal of Medical Informatics, Informatics for Health and Social Care, Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, International Journal of Innovation and Learning, and other international refereed journals and conference proceedings 107