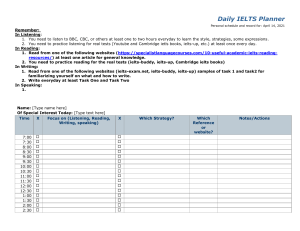

![Key-to-IELTS-Success-2021 [@ielts weekly]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/026177397_1-3694c3cfc14593d0153e0e520df5fcf7-768x994.png)