Conjunctions

263

Definition and types. A conjunction is a function word that connects sentences, clauses, or words within a clause {my daughter graduated from

college in December, and my son will graduate from high school in May

[and connects two sentences]} {I said hello, but no one answered [but

connects two clauses]} {we’re making progress slowly but surely [but

joins two adverbs within an adverbial clause]}. In Standard English,

conjunctions connect pronouns in the same case {he and she are colleagues} {the teacher encouraged her and me}. A pronoun following the

conjunction than or as is normally in the nominative case even when the

clause that follows is understood {you are wiser than I [am]} {you seem as

pleased as she [does]}—except in informal or colloquial English {you are

wiser than me}. In the latter instance, than can be read as a preposition.

264

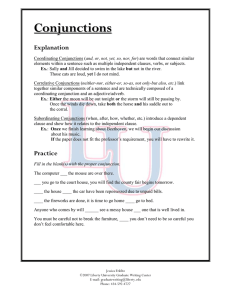

Types of conjunctions: simple and compound. A conjunction may be

simple, a single word such as and, but, if, or, or though. Most are derived

from prepositions. Compound conjunctions are single words formed by

combining two or more words. Most are relatively modern formations

and include words such as although, because, nevertheless, notwithstanding,

and unless. Phrasal conjunctions are connectives made up of two or more

separate words. Examples are as though, inasmuch as, in case, provided

that, so that, and supposing that. The two main classes of conjunctions are

coordinating and subordinating.

265

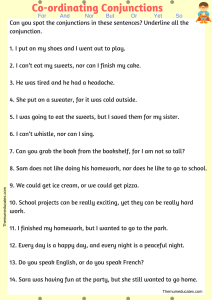

Coordinating conjunctions. Coordinating conjunctions join words or

groups of words of equal grammatical rank, i.e., elements of independent

and equal rank, such as two nouns, two verbs, two phrases, or two clauses

{are you speaking to him or to me?} {the results are disappointing but not

discouraging}. Coordinating conjunctions are further broken down into

copulative, adversative, disjunctive, and final. A coordinating conjunction may be either a single word or a correlative conjunction.

266

Correlative conjunctions. Correlative conjunctions are conjunctions used

in pairs, often to join successive clauses that depend on each other to form

a complete thought. Correlative conjunctions must frame structurally

identical or matching sentence parts {she wanted both to win the gold

medal and to set a new record}; in other words, each member of the pair

146

Conjunctions

should immediately precede the same part of speech {they not only read

the book but also saw the movie} {if the first claim is true, then the second claim must be false}. Some examples of correlative conjunctions are

as–as; if–then; either–or, neither–nor; both–and; where–there; so–as; and

not only–but also. For more on parallelism with correlative conjunctions,

see § 332.

267

Copulative conjunctions. Copulative or additive coordinating conjunctions denote addition. The second clause states an additional fact that is

related to the first clause. These conjunctions include and, also, moreover,

and no less than {one associate received a raise, and the other was promoted} {the jockeys’ postrace party was no less exciting than the race

itself}.

268

Adversative conjunctions. Adversative or contrasting coordinating conjunctions denote contrasts or comparisons. The second clause, sometimes

called an adversative clause, usually qualifies the first clause in some way.

These conjunctions include but, still, yet, and nevertheless {the message is

sad but inspiring} {she’s earned her doctorate, yet she’s still not satisfied

with herself}.

269

Disjunctive conjunctions. Disjunctive or separative coordinating conjunctions denote separation or alternatives. Only one of the statements

joined by the conjunction may be true; both may be false. These conjunctions include either, or, else, but, nor, neither, otherwise, and other {that bird

is either a heron or a crane} {you can wear the blue coat or the green one}.

270

Final conjunctions. Final or illative coordinating conjunctions denote

inferences or consequences. The second clause gives a reason for the first

clause’s statement, or it shows what has been or ought to be done in view

of the first clause’s expression. These conjunctions include consequently,

for, hence, so, thus, therefore, as a consequence, as a result, so that, and so

then {he had betrayed the king; therefore, he was banished} {it’s time to

leave, so let’s go}.

271

Subordinating conjunctions. A subordinating conjunction connects

clauses of unequal grammatical rank. The conjunction introduces a

clause that is dependent on the independent clause {follow this road

until you reach the highway} {that squirrel is friendly because people

feed it} {Marcus promised that he would help}. A pure subordinating

147

The Traditional Parts of Speech

conjunction has no antecedent and is not a pronoun or an adverb {take a

message if someone calls}.

272

Special uses of subordinating conjunctions. Subordinating conjunctions

or conjunctive phrases often denote the following relationships:

1. Comparison or degree—e.g., than (if it follows comparative adverbs

or adjectives, or if it follows else, rather, other, or otherwise), as, else,

otherwise, rather, as much as, as far as, and as well as {is a raven less

clever than a magpie?} {these amateur musicians play as well as

professionals} {it’s not true as far as I can discover}.

2. Time—e.g., since, until, as long as, before, after, when, as, and while

{while we waited, it began to snow} {the tire went flat as we were

turning the corner} {we’ll start the game as soon as everyone

understands the rules} {the audience returned to the auditorium

after the concert’s resumption was announced}.

3. Condition or assumption—e.g., if, though, unless, except, without,

and once {once you sign the agreement, we can begin remodeling

the house} {your thesis must be presented next week unless you

have a good reason to postpone it} {I’ll go on this business trip if

I can fly first class}.

4. Reason or concession—e.g., as, inasmuch as, why, because, for, since,

though, although, and albeit {since you won’t share the information, I can’t help you} {Sir John decided to purchase the painting

although it was very expensive} {she deserves credit because it

was her idea}.

5. Purpose or result—e.g., that, so that, in order that, and such that {we

dug up the yard so that a new water garden could be laid out} {he

sang so loudly that he became hoarse}.

6. Place—e.g., where {I found a great restaurant where I didn’t expect

one to be}.

7. Manner—e.g., as if and as though {he swaggers around the office

as if he were an executive}.

8. Appositions—e.g., and, or, what, and that {the buffalo, or American

bison, was once nearly extinct}.

9. Indirect questions—e.g., whether, why, and when {he could not say

whether we were going the right way}.

273

Adverbial conjunctions. An adverbial conjunction connects two clauses

and also qualifies a verb {the valet has forgotten where Alvaro’s car is

parked [where qualifies the verb is parked]}. There are two types of

148

Conjunctions

adverbial conjunctions: relative and interrogative. A relative adverbial

conjunction does the same job as any other adverbial conjunction, but it

has an antecedent {do you recall that cafe where we first met? [cafe is the

antecedent of where]}. An interrogative adverbial conjunction indirectly

states a question {Barbara asked when we are supposed to leave [when

poses the indirect question]}. Some common examples of conjunctive

relative adverbs are after, as, before, until, as, now, since, so, when, and where.

Interrogative adverbs are used to ask direct and indirect questions; the

most common are why, how, when, where, and what {I don’t see how you

reached that conclusion}.

274

Expletive conjunctions. An expletive conjunction is a conjunction that

connects two thoughts that are not expressed in the same sentence. The

conjunction refers to a preceding sentence and often, but not always,

begins the sentence {but then the professor pointed out the flaws in their

reasoning} {survival is thus the most important motivation}.

275

Disguised conjunctions. So-called disguised conjunctions are participles

that have long been used as conjunctions—e.g., barring, considering, provided, regarding, speaking, and supposing. A disguised conjunction does not

have a subject, while a verb does {considering the poor road conditions,

we traveled swiftly [considering as a preposition]} {we traveled swiftly,

considering the poor road conditions [considering as a disguised conjunction]} {the committee is considering a budget increase [considering as a

verb]}. The key distinction between a conjunction and a participial preposition is that a conjunction does not take an object but a preposition does.

(See §§ 243, 246.) Compare the steak and eggs were perfectly cooked (eggs

is part of the subject, not the object of and) with the steak comes with eggs

(eggs is the object of the preposition with). The key distinction between a

conjunction and an adverb is that a conjunction does not qualify any part

of speech. Compare the use of before in I’ve seen this movie before (adverb)

with the cart is standing before the horse (preposition) and it began raining

before we left (conjunction).

276

“With” used loosely as a conjunction. The word with is sometimes used

as a quasi-conjunction meaning “and.” This construction is nonstandard:

the with-clause appears to be tacked on as an afterthought. For example,

the sentence *Everyone else grabbed the easy jobs with me being left to scrub

the oven could be revised as Since everyone else grabbed the easy jobs, I had

to scrub the oven. Or it could also be split into two independent clauses

149

The Traditional Parts of Speech

joined by a semicolon—e.g., Everyone else grabbed the easy jobs; I had to

scrub the oven. Instead of with, find the connecting word, phrase, or punctuation that best shows the relationship between the final thought and

the first, and recast the sentence.

277

Beginning a sentence with a conjunction. There is a widespread belief—

one with no historical or grammatical foundation—that it is an error to

begin a sentence with a conjunction such as and, but, or so. In fact, a substantial percentage (often as many as 10%) of the sentences in first-rate

writing begin with conjunctions. It has been so for centuries, and even

the most conservative grammarians have followed this practice. Charles

Allen Lloyd’s 1938 words fairly sum up the situation as it stands even

today:

Next to the groundless notion that it is incorrect to end an English sentence

with a preposition, perhaps the most widespread of the many false beliefs

about the use of our language is the equally groundless notion that it is

incorrect to begin one with “but” or “and.” As in the case of the superstition

about the prepositional ending, no textbook supports it, but apparently

about half of our teachers of English go out of their way to handicap their

pupils by inculcating it. One cannot help wondering whether those who

teach such a monstrous doctrine ever read any English themselves.5

Still, but as an adversative conjunction can occasionally be unclear at

the beginning of a sentence. Evaluate the contrasting force of the but in

question, and see whether the needed word is really and; if and can be

substituted, then but is almost certainly the wrong word. Consider this

example: He went to school this morning. But he left his lunch box on the

kitchen table. Between those sentences is an elliptical idea, since the two

actions are in no way contradictory. What is implied is something like

this: He went to school, intending to have lunch there, but he left his lunch

behind. Because and would have made sense in the passage as originally

stated, but is not the right word—the idea for the contrastive but should

be explicit.

To sum up, then, but is a perfectly proper way to open a sentence,

but only if the idea it introduces truly contrasts with what precedes. For

that matter, but is often an effective way of introducing a paragraph that

develops an idea contrary to the one preceding it.

5

150

Charles Allen Lloyd, We Who Speak English: And Our Ignorance of Our Mother Tongue (New York:

Thomas Y. Crowell, 1938), 19.

Conjunctions

278

Beginning a sentence with “however.” However has been used as a conjunctive adverb since the 14th century. Like other adverbs, it can be used

at the beginning of a sentence. But however is more ponderous and has

less impact than the simple but. As a matter of style, however is more effectively used within a sentence to emphasize the word or phrase that precedes it {The job seemed exciting at first. Soon, however, it turned out to

be exceedingly dull}. For purposes of euphony and flow, not of grammar,

many highly accomplished writers shun the sentence-starting however as

a contrasting word. Yet the word is fine in that position in the sense “in

whatever way” (not followed by a comma) {however that may be, we’ve

now made our decision}.

279

Conjunctions and the number of a verb. Coordinating and disjunctive

conjunctions affect whether a verb should be plural or singular. Conjunctions such as and and through indicate that group sentence elements

impart plurality, so a plural verb is correct {the best vacation and the worst

vacation of my life were on cruises} {the first through seventh innings

were scoreless}. But conjunctions such as or and either–or distinguish

the elements and do not impart plurality, so the singular verb is used if

the elements are singular {a squirrel or a chipmunk raids the bird feeder

every day} {either William or Henry dances with Lady Hill}. Other types

of conjunctions have no effect on the verb’s number; for example, if and

is used as a copulative conjunction, the verb that follows may be singular

{Andrés’s bicycle was new, and so was his helmet}.

151

Interjections

280

Definition. An interjection or exclamation is a word, phrase, or clause

that denotes strong feeling {never again!} {you don’t say!}. An interjection has little or no grammatical function in a sentence; it is used absolutely {really, I can’t understand why you put up with the situation} {oh

no, how am I going to fix the damage?} {hey, it’s my turn next!}. It is

frequently allowed to stand as a sentence by itself {Oh! I’ve lost my wallet!} {Ouch! I think my ankle is sprained!} {Get out!} {Whoa!}. Introductory words like well and why may also act as interjections when they are

meaningless utterances {well, I tried my best} {why, I would never do

that}. The punctuation offsetting the interjections distinguishes them.

Compare the different meanings of Well, I didn’t know him with I didn’t

know him well, and Why, here you are! with I have no idea why you are here

and Why? I have no idea.

281

Usage generally. Interjections are natural in speech {your order should

be shipped, oh, in eight to ten days} and frequently used in dialogue

(and formerly in poetry). As a midsentence interrupter, an interjection

may direct attention to one’s phrasing or reflect the writer’s or speaker’s

attitude toward the subject, especially with informal and colloquial tone

{because our business proposal was, ahem, poorly presented, our budget

will not be increased this year}.

282

Functional variation. Because interjections are usually grammatically

independent of the rest of the sentence, all other parts of speech may

be used as interjections. A word that is classified as some other part of

speech but used with the force of an interjection is called an exclamatory noun, exclamatory adjective, etc. Some examples are good! (adjective);

idiot! (noun); help! (verb); indeed! (adverb); me! (pronoun); and! (conjunction); quickly! (adverb).

283

Words that are exclusively interjections. Some words are used only as

interjections—for example, ouch, whew, ugh, psst, and oops.

284

Punctuating interjections. An exclamation mark usually follows an

interjection {oh no!} or the point where the strong feeling ends {oh no,

I’ve forgotten the assignment!}. But as with other interrupters, when an

152

Interjections

interjection appears midsentence, it is typically set off by commas, parentheses, or dashes {he’s a nice enough lad, but his manners are—forgive

me—somewhat lacking}.

285

“O” and “oh.” The interjections O and oh are similar in appearance but

distinguished in meaning and use. O is always capitalized and is typically

unpunctuated as a form of classically stylized direct address {O Jerusalem!}. It most often appears in poetry (especially pre-20th-century

poetry). Oh takes the place of other interjections to express an emotion such as pain {ow!}, surprise {what!}, wonder {strange!}, or aversion

{ugh!}. It is lowercase if it doesn’t start the sentence, and it is typically

followed by a comma {oh, why did I have to ask?} {the scenery is so beautiful, but oh, I can’t describe it!}. Oh is more common in prose than in

poetry.

153