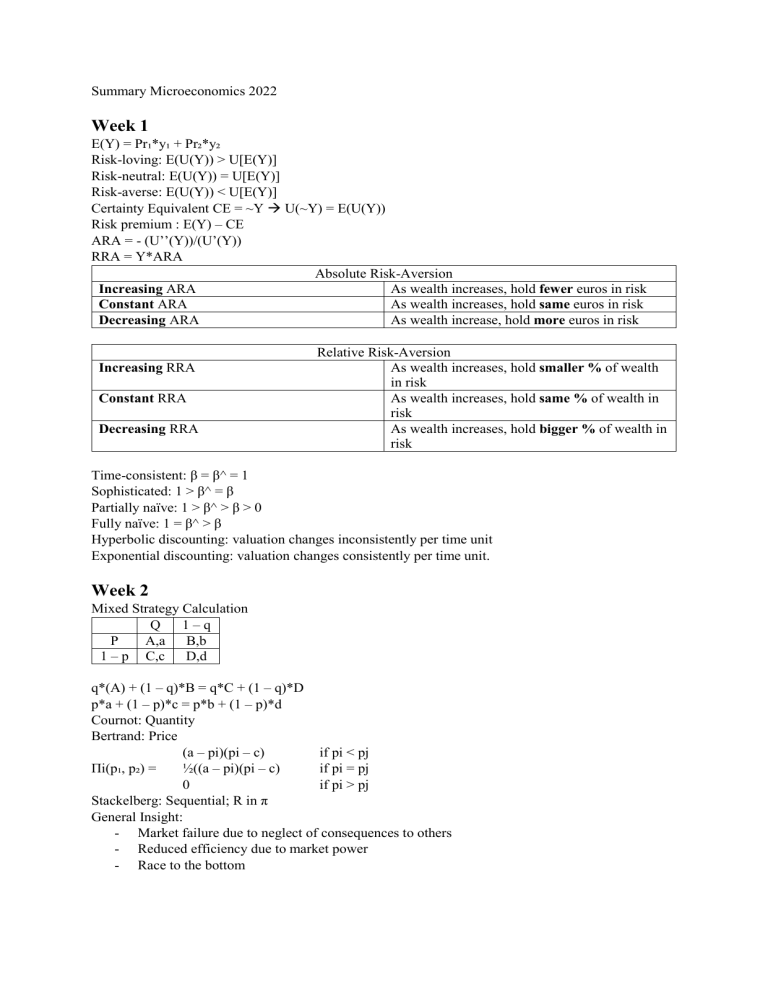

Summary Microeconomics 2022 Week 1 E(Y) = Pr₁*y₁ + Pr₂*y₂ Risk-loving: E(U(Y)) > U[E(Y)] Risk-neutral: E(U(Y)) = U[E(Y)] Risk-averse: E(U(Y)) < U[E(Y)] Certainty Equivalent CE = ~Y U(~Y) = E(U(Y)) Risk premium : E(Y) – CE ARA = - (U’’(Y))/(U’(Y)) RRA = Y*ARA Absolute Risk-Aversion Increasing ARA As wealth increases, hold fewer euros in risk Constant ARA As wealth increases, hold same euros in risk Decreasing ARA As wealth increase, hold more euros in risk Increasing RRA Constant RRA Decreasing RRA Relative Risk-Aversion As wealth increases, hold smaller % of wealth in risk As wealth increases, hold same % of wealth in risk As wealth increases, hold bigger % of wealth in risk Time-consistent: β = β^ = 1 Sophisticated: 1 > β^ = β Partially naïve: 1 > β^ > β > 0 Fully naïve: 1 = β^ > β Hyperbolic discounting: valuation changes inconsistently per time unit Exponential discounting: valuation changes consistently per time unit. Week 2 Mixed Strategy Calculation Q 1–q P A,a B,b 1 – p C,c D,d q*(A) + (1 – q)*B = q*C + (1 – q)*D p*a + (1 – p)*c = p*b + (1 – p)*d Cournot: Quantity Bertrand: Price (a – pi)(pi – c) if pi < pj Πi(p₁, p₂) = ½((a – pi)(pi – c) if pi = pj 0 if pi > pj Stackelberg: Sequential; R in π General Insight: - Market failure due to neglect of consequences to others - Reduced efficiency due to market power - Race to the bottom Week 3 # of strategies = # of action^(# of decision nodes) - In case of perfect information Credibility depends on alternatives and relative costs of delay Week 4 Complete information: all elements of the structure of the game are common knowledge. Incomplete when one player has private information on the structure of the game. Perfect information: each information set of different decision points in the game tree contains only one decision point. A game of incomplete information always has imperfect information! English Auction - Open; common value (is known after auction) - Ascending - Winner: highest bidder - Price: highest bid - Dominant strategy: bid no more than your valuation Vickery auction - Sealed private auction; personal valuations - Winner: highest bidder - Price: second highest offer - No strategic behaviour possible: bid your valuation - More bidders = higher expected revenue for the seller Dutch Auction - Open; common value (is known after auction) - Descending - Winner: highest bidder/ first to bid - Price: highest bid/ first bid - Strategy: trade-off between valuation and profit; shading First-Price Auction - Sealed private auction: private valuations - Winner: highest bidder - Price: highest offer - Strategy: trade-off between valuation and profit; shading Expected value seller: 𝐸[𝑉𝑘(n)]= 100 ∗ (𝑛 + 1 – 𝑘)/(𝑛 + 1) on U[0,100]: Expected value buyer: E[𝑉₁(𝑛−1)]= 𝑣₁ ∗ (𝑛 − 1)/ 𝑛 Winner’s curse: overestimation of the product Week 6 Complete and imperfect: Moral hazard, with: search goods, experience goods, trust goods Hidden action and hidden knowledge Incomplete and imperfect: Adverse selection - Gresham’s law Countered with; Signalling, first move by the informed party, e.g. quality, education and entry deterrence. Nature chooses type of agent, agent takes action, principal adjusts beliefs, all ICC for all types are met. Equilibria; pooling, revealing nothing and separating, revealing the “type” of player Screening, first move by the uninformed party, e.g. job interview. No beliefs in the game, requirements are either met or not, all ICC for all types are met. Week 7 Efficiency wage theory models, all starting with higher wages: - Nutrition - Selection - Turnover - Shirking - Gift-Exchange Reciprocity could explain increasing effort when wages increase. Incentive schemes: Pygmalion effect (positive) Galatea effect (negative) Might focus too broadly Contradiction; lowest on ladder work hardest to climb up Extrinsic motivation Intrinsic motivation Relative-price effect Crowding-out; - Recognition - Fairness - Self-determination: o Autonomy o Mastery o Purpose - Personal relationship between Principal and Agent - Contingence (onvoorspelbaarheid) - Acknowledgement Week 8 Allow for “other regarding” preferences can change the predictions of many economics models. “other regarding” preferences can explain positive and negative actions towards other players. “other regarding” preferences can relate to other people’s outcomes or intentions. Bounded rationality: awareness, reasoning, etc. Endowment effect Reference-dependent preferences Prospect Theory: People evaluate outcomes in terms of gains and losses compared to a reference point Values of gains and losses are weighted with decision weights 𝑉 = 𝜋(𝑃𝑌𝑙𝑜𝑠𝑠) 𝑣(𝑌𝑙𝑜𝑠𝑠) + 𝜋(𝑃𝑌𝑔𝑎𝑖𝑛) 𝑣(𝑌𝑔𝑎𝑖𝑛) 𝑉 = 𝜋(𝑃𝑌𝑙𝑜𝑠𝑠) 𝑣(𝑌𝑙𝑜𝑠𝑠) + 𝜋(𝑃𝑌𝑔𝑎𝑖𝑛) 𝑣(𝑌𝑔𝑎𝑖𝑛) People are loss averse Problems laboratory results: - Moral and ethics - Scrutiny - Context - Self-selection - Stakes Markets exploit biases, society and institutions respond by improve welfare through; money incentives, choice architecture (nudging) and values and norms. Literature Camerer, C. & R.H. Thaler (1995), Ultimatums, Dictators and Manners, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9 (2), Spring, pp. 209-219. Standard game theory assumes self-interest. If both players are income maximizers, and Proposers know this, then the Proposer should offer a penny (or the smallest unit of currency available), and the Responder should accept. Frey’s “Motivation as a limit to pricing” The answer to this is the summary of the entire article. Pricing (monetary incentives like flexible wage schemes) can lead to crowding out of intrinsic motivation. That may result in workers adjusting their level of effort downwards (crowding out of intrinsic motivation) if they feel that their efforts are not recognized by the employer or if they feel that the monetary incentives are unfair or if they feel that the control that they have over their own work is taken away from them. The article names several conditions when intrinsic motivation tends to be high (interesting task, lots of self-determination etc). In those situations, the danger of crowding out can be high. Possible misattribution (being attributed a lower effort than is the case in reality) and (reduction of) overjustification (being “too motivated”, both extrinsically and intrinsically) will again increase the danger of crowding out. Misattribution may be a problem even when the employer attributes the right amount of effort to the worker since on average people overestimate their abilities (see also Shirking and Work morale – we cannot really see the two Frey articles apart from each other) and the worker will feel as if his effort is not appreciated enough. In case of overjustification, the worker will bring down his motivation by lowering the type of motivation he has control of (being intrinsic motivation). Frey argues that monitoring has positive effects on the amount of output of the ‘rightly’ monitored workers (crowding in of intrinsic motivation). However, there might be a counteracting effect on those workers who feel that they need not be monitored: it signals that the principal does not know their real production/commitment. It might be that these workers feel discouraged to perform better than the minimum standard (the principal did not notice that they were doing more, anyway). The gain in increased productivity at the bottom is ‘matched by a potential loss at the top of the distribution. The net effect might easily be negative. (NB Frey is a Swiss professor…) The specific conditions that are mentioned by Frey (p. 1525) are - regulation/monitoring ineffective and/or costly - lots of discretionary decisions - decisions made collectively (team work) - quality of work hard to measure Fehr et al., “Does fairness prevent market clearing?” Gift-exchange efficiency wages (now called ‘fair wage’ hypothesis). It is measures whether a ‘gift’ of a high wage is reciprocated by the worker by exerting higher effort. The experiment is an auction during a time of unemployment (so employers do not have to offer higher wages in order to attract workers). Employers offer higher than equilibrium wages and workers react by putting in more effort. Motivation Theory The relative price effect: Following the standard economic principal agent theory, external interventions impose a higher marginal cost (e.g. by imposing a threat of being fired) on shirking, or increase the marginal monetary benefit of performing (e.g. being paid a higher wage when putting in more effort). The crowding effect: all interventions originating from outside the person under consideration, i.e. both positive monetary rewards and regulations accompanied by negative (monetary or other) sanctions may affect intrinsic motivation (by affecting the marginal intrinsic benefit of performing, i.e. the marginal utility one derives from putting in effort). External interventions may crowd-out or crowd-in intrinsic motivation (or leave it unaffected, as is the implicit assumption in mainstream theory). The direction Intermediate Microeconomics, Games and Behaviour ECB2VMIE 2022-2023 8 and magnitude in which an agent adjusts his or her intrinsic motivation depends on how pricing affects the marginal benefits of acting in accordance with one’s inner motivation (e.g. does one derive more or less utility from acting according to e.g. one’s norms and values). External interventions raise intrinsic motivation if the marginal benefit of performing is increased and the effect of disciplining the agent is further strengthened by a crowding-in effect. In this case both the relative price effect and the crowding effect work in the same direction. The opposite occurs if the external intervention undermines intrinsic motivation (crowding out) and thus negatively affects the agent’s marginal benefit from performing (e.g. when an agent feels that the intervention is unfair or incorrect (“misattribution”), the marginal utility from putting in effort decreases). Akerlof & Kranton’s article on “Economics of Identity” In our utility function, identity is based on social categories, C. Each person j has an assignment of people to these categories, cj, so that each person has a conception of her own categories and that of all other people. Prescriptions P indicate the behaviour appropriate for people in different social categories in different situations. Utility depends on j’s identity or self-image Ij, as well as on the usual vectors of j’s actions, aj, and others’ actions, a-j. A person j’s identity Ij depends, first of all, on j’s assigned social categories cj. The social status of a category is given by the function Ij(·), and a person assigned a category with higher social status may enjoy an enhanced self-image. Identity further depends on the extent to which j’s own given characteristics ej match the ideal of j’s assigned category, indicated by the prescriptions P. Finally, identity depends on the extent to which j’s own and others’ actions correspond to prescribed behaviour indicated by P. Gender identity: There is a set of categories C, ‘‘man’’ and ‘‘woman,’’ where men have higher social status than women. cj describes j’s own gender category as well as j’s assignment for everyone else in the population. P associates to each category basic physical and other characteristics that constitute the ideal man or woman as well as specifies behaviour in different situations according to gender. E.g., the ideal woman is female, thin, and should always wear a dress.