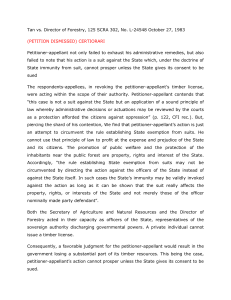

State Immunity Doctrine: Legal Analysis & Case Study

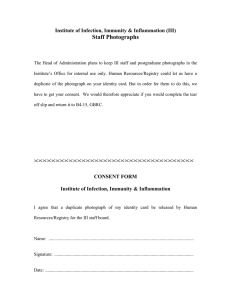

advertisement