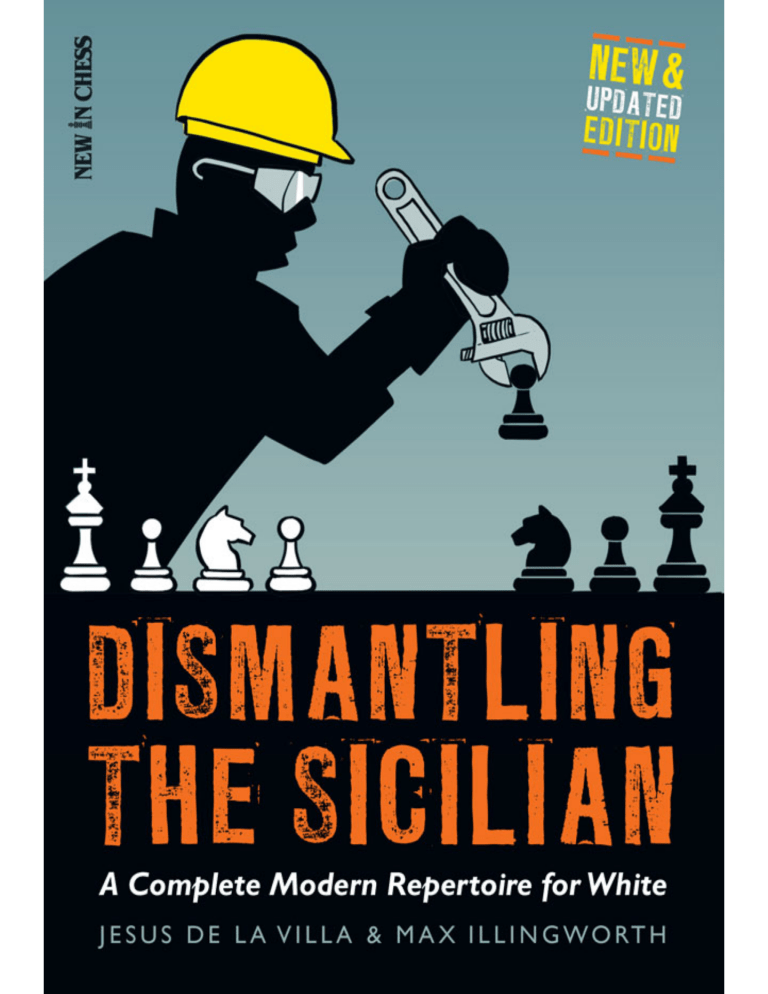

Jesus de la Villa & Max Illingworth Dismantling the Sicilian A Complete Modern Repertoire for White New & Updated Edition New In Chess 2017 © New In Chess First Edition 2009 New & Updated Edition 2017 Published by New In Chess, Alkmaar, The Netherlands www.newinchess.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. Cover design: Volken Beck Supervision: Peter Boel Proofreading: Frank Erwich Production: Anton Schermer Have you found any errors in this book? Please send your remarks to editors@newinchess.com. We will collect all relevant corrections on the Errata page of our website www.newinchess.com and implement them in a possible next edition. ISBN: 978-90-5691-752-4 Contents Explanation of symbols . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 Introduction to the new edition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7 Introduction to the first edition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13 Chapter 1 – Second move sidelines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17 Chapter 2 – 2...♘c6 sidelines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26 Chapter 3 – The Lowenthal & the Kalashnikov . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35 Chapter 4 – The Accelerated Dragon 4...g6 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50 Chapter 5 – The Sveshnikov 5...e5 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72 Chapter 6 – Sidelines after 2...e6 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100 Chapter 7 – The Taimanov 4...♘c6 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122 Chapter 8 – The Paulsen 5.♘c3 without 5...♕c7 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143 Chapter 9 – The Paulsen 5.♘c3 ♕c7 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 159 Chapter 10 – 2...d6 sidelines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 187 Chapter 11 – The Scheveningen . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 196 Chapter 12 – The Dragon 5...g6 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 203 Chapter 13 – The Richter-Rauzer without 8...♗d7 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 223 Chapter 14 – The Richter-Rauzer 8...♗d7 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 249 Chapter 15 – The 6.h3 Najdorf . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 268 Chapter 16 – The 6.♗e2 Najdorf . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 312 Chapter 17 – What others recommend... and why I disagree . . . . . . . . . . 334 Index of variations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 359 Index of players . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 364 Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 367 5 KEY TO SYMBOLS ! ? !! ?? !? ?! = a good move a weak move an excellent move a blunder an interesing move a dubious move only move equality unclear position with compensation for the sacrificed material White stands slightly better Black stands slightly better White has a serious advantage +-+ Black has a serious advantage White has a decisive advantage Black has a decisive advantage with an attack with initiative with counterplay with the idea of better is N + # worse is novelty check mate Introduction to the new edition The previous edition of Dismantling the Sicilian starts as follows: ‘This book deals with the study of the Sicilian Defence; however, the theoretical development has been so significant in recent years, that trying to cover all the variations of such a popular defence is somewhat a utopian dream. Therefore, this book is content to offer a repertoire for White based on 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 followed by 3.d4.’ Eight years on, it may seem that the ‘utopian dream’ could be extended to a one-volume repertoire book against the Sicilian. After all, last year the esteemed author GM Parimarjan Negi finished the three-volume series Grandmaster Repertoire: 1.e4 vs. the Sicilian, and the most recent Open Sicilian repertoire for White, Attacking the Flexible Sicilian by GM Vassilios Kotronias and IM Semko Semkov, covered only 2...e6 Open Sicilians in 400 pages. As a grandmaster and theoretician, I enjoy such detailed, specific works, but as a coach, I completely understand that amateur players are reluctant to study well over a thousand pages of material for one opening, however compelling the repertoire is. My opening philosophy is even more principled than Jesus de la Villa’s, in that I believe in playing the best moves against everything. That may seem like a lot more work, but my experience suggests the opposite. We will have less need to change our repertoire or rely on the element of surprise, while playing critically in the opening often carries over to our middlegame and endgame play. Furthermore, the ever-improving chess engines have demonstrated that not only are there often several equivalent moves in the opening phase, but that in many cases the best move is a rare or new continuation. In that sense, you could argue that a strong novelty is an unpleasant surprise. And you will find hundreds of novelties in this book. As this is a flexible repertoire with some reserve options for White, I should mention an exception to my above philosophy – against the Paulsen (1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6), I adhered to the previous edition’s recommendation of 5.Nc3, even though I believe in White’s chances for an edge after 5.Bd3 and 5.c4. These two moves were covered very thoroughly in the aforementioned Negi and Kotronias/Semkov books respectively. Recommending 5.Nc3 best matched my writing philosophy: to offer as much original material as possible, as every serious player has access to a large database and chess engine. Furthermore, I can say from my own experience that a nuanced understanding of Hedgehog structures is required to make use of White’s small edge, whereas White’s play in the 5.Nc3 variation is more tactical and natural for a club player to execute. Although this is a new edition of Dismantling the Sicilian, I found it necessary to change the basic framework of the repertoire. Granted, I was extremely successful with De la Villa’s English Attack-based repertoire in my own games, and I can even attribute my first win against a grandmaster (also the game that secured my FM title) in a classical game to the book: Max Illingworth 2289 Darryl Johansen 2457 Parramatta 2010 (8) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 d6 6.Be3 Nf6 7.f3 Be7 8.Qd2 0-0 9.0-0-0 a6 10.g4 Nd7 11.h4 Nde5 12.Qg2 b5 13.g5 Bd7 14.Kb1 Nxd4 15.Bxd4 b4 16.Ne2 Qc7 17.f4 Rfc8 18.Ng3 Nc6 19.Be3 d5 20.exd5 b3 21.g6 bxa2+ 22.Ka1 Nb4 23.gxf7+ Kxf7 24.dxe6+ Bxe6 25.c3 Rd8 26.Re1 Nd5 27.Bd4 Nf6 28.Rg1 Rg8 29.Ne4 Nh5 30.f5 Bxf5 31.Ng5+ Bxg5 32.Qd5+ 1-0 As I show in the uniquely New In Chess chapter called ‘What others recommend... and why I disagree’ (no. 17), overviewing the recommendations of the previous edition as well as Negi’s series, the English Attack has been neutralised by modern computers. Particularly the modern main line of the Najdorf/Scheveningen English Attack has been virtually analysed to a draw by deep engine analysis. You will still have plenty of opportunities to charge Garry the g-pawn in this repertoire – with the difference that mostly we will be supporting this aggression with h2-h3, Be2 or f2f4. Furthermore, it has recently become popular in the Open Sicilian to castle queenside with our queen more aggressively placed on e2 or f3, as you can study in the Taimanov, Scheveningen and Najdorf chapters. The theory is still developing in these systems, but I’ve made a strong case that White is fighting for an opening advantage, which can easily increase if Black settles for natural developing moves (as is frequently the case at the amateur level). I’ve noticed on online chess forums and blogs that readers desire clear explanations of ideas, and lament getting bogged down in swathes of variations, most of which they are unlikely to face over the board. This book doesn’t skimp on detail either, but I have divided each chapter into a ‘theoretical overview’ section and an ‘illustrative games’ section, so you may play the repertoire successfully without needing to read cover-to-cover. Inexperienced players can play through the games in the ‘illustrative games’ section and quickly apply the typical middlegame plans, themes and tactics. Advanced players can find all the theory they need to know (and a bit more!) explained in the theoretical overviews. Finally, professional players can subsequently work through the illustrative games for further detail, as well as reserve options to complicate the opponent’s preparation. There are some inevitable wide branches for Black’s most flexible systems, so you may choose to skip the sidelines in each branch on a first read for a ‘quick repertoire’. In principle, I have offered alternatives only where I was unable to clearly prove a white advantage, but there are some exceptions where I included another good option for its similarity with another repertoire line, or to improve our understanding of the Open Sicilian. All the illustrative games are referenced in the ‘theoretical overview’ sections, though I have not altered the move orders of the games, as the reader will benefit from acquaintance with different move orders (and may well apply some of them to his or her repertoire). You will also find a summary of each chapter, with the engine’s evaluations at a high depth of each major variation (to the nearest 0.05) to indicate the main theoretical conclusions. I lacked the space to include a separate chapter for exercises, but I have selected many of the diagrams in such a way that they (excepting those indicating important branchings, and those in the ‘What others recommend...’ chapter) serve as a ‘White to play’ puzzle. You will find the solution in the text following the diagram, which will consolidate key tactics, move orders, plans and novelties in your memory. You may find solving these diagram positions in the ‘illustrative games’ section useful for improving your overall skill. Those comparing this book to the previous edition will notice that I have merged some chapters together, namely the various sidelines are grouped by ‘Second move sidelines’, ‘2...Nc6 sidelines’, ‘2...e6 sidelines’ and ‘2...d6 sidelines’. This made it easier to divide the particularly flexible Paulsen, Richter-Rauzer and Najdorf Sicilians into two chapters each, so they would be better digestible. It was in these three systems (together with the Sveshnikov and the Four Knights Sicilian) that I was unable to conclusively prove an advantage for White. Therefore, I have offered several options for White, so the opponent cannot memorise one line against our entire repertoire. To portray the spirit of the repertoire, I will elaborate on these alternatives here. In the Paulsen with 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Bd3 Nf6, my main recommendation is now 7.0-0, but the flexible 7...Be7 proved very resilient. I show two ways to handle it, and also analyse two games with the old recommendation 7.f4 in the ‘illustrative games’ section. It might seem surprising that the Four Knights Sicilian is hard to prove a serious edge against, but I cover both 9.Bd3 and 9.exd5 in the main line. In the ‘What others recommend...’ chapter, I also share a wrinkle against 6.Nxc6 that is not mentioned in Attacking the Flexible Sicilian. Those who have done their own work on the opening can surely recognize the feeling of finding an edge against everything except one rare sideline! That was the case in the Rauzer main line with 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f3 Be7, when Black plays an early ...Nxd4. I cover both the old recommendation 10.h4 and 10.Kb1 in the theoretical overview for that chapter for some flexibility, and in the illustrative games you will even find a way to avoid it with 10.Be3!?, which could prove a starting point for your own investigations. Amusingly, this reminds me of the main rule of thumb I learned from writing this book – the once maligned Nxc6 exchange is often a good early middlegame move for White in the Open Sicilian! As for the Sveshnikov, my main recommendation is 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3, and I offer some alternative options against the more drawish lines, but I also present a repertoire with 9.Bxf6 in ‘What others recommend...’, explaining the problem line that forced me to find something better. Of course, most of the world’s elite currently avoid the Sveshnikov with 3.Bb5, but my variations have the advantage that Black finds it extremely hard to play for a win without accepting a disadvantage. Finally, the Najdorf is the one major line (the Nimzowitsch, 2...Nf6, doesn’t qualify) where I offer two different options right at the start – the modern main line 6.h3 is my main recommendation, supporting g2-g4 while avoiding certain problem lines against 6.Be3 and 6.f3 respectively, but for a lower theoretical workload (and similar ideas) I give a secondary recommendation of 6.Be2. This is partly motivated by the fact that I consider the Najdorf the only repertoire foundation against 1.e4 that offers considerable winning chances at the professional level without accepting an objective disadvantage, though I understand that’s a very contentious view! Owners of the previous edition may have noticed that I have taken a different approach to the Illustrative games themselves. Since the 2009 edition of Dismantling the Sicilian, correspondence games have become more and more theoretically significant, and about a third of the selected games are in fact from correspondence chess. This is not only because these games are of a higher quality than over-the-board play, but I also found them to contain many interesting middlegame and endgame motifs. Although I am not a correspondence player, I found from my study of these games that they are not simply ‘engine battles’ as many assume, but rather a valuable lesson in how to find ideas beyond the scope of the engine. At the same time, over-the-board games are a more practical struggle, and there are many typical tactics and ideas that especially strong players know to anticipate or avoid. The sharp nature of many of my recommendations means that even the world’s top players can falter in the complications, but we can also learn a lot from the improvements over and alternatives to these games, and not neglect the ‘human’ component of tournament play. In this book, I have covered games up to and including June 30, 2017. A larger or multi-volume book might contain a historical overview of each variation and detailed explanations of every move, but early games can be looked up in a database, and I prefer succinct, punchy explanations. I haven’t held anything back in my coverage, analysis of and views about this Open Sicilian repertoire for White. While theoreticians, analysts, players and stronger engines will be investigating my ideas more deeply, and will be finding improvements over my analysis for both sides, I’m confident that the basic repertoire, and the understanding you will acquire from my explanations, will be a strong framework for your continued success playing the Open Sicilian as White. I’d like to express my gratitude to Jesus de la Villa for giving me the opportunity to work on this updated edition of Dismantling the Sicilian, a project which remains topical and influential today. I’m also grateful to Jesus for his encouragement, and for the positive influence the previous edition of his book had on my chess development and career. I am pleased that I can give some of that back in this collaborative second edition. Max Illingworth Sydney, Australia, September 2017 Introduction to the first edition This book deals with the study of the Sicilian Defence; however, the theoretical development has been so significant in recent years, that trying to cover all the variations of such a popular defence is somehow a utopian dream. Therefore, this book is content to offer a repertoire for White based on 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 followed by 3.d4. The Sicilian is the most widely used defence. According to different databases and different periods, percentages may vary, but will be around 20%; if we take into account only those games starting with 1.e4, the percentage of Sicilians may reach 40%. Furthermore, those figures have been increasing in recent years. Therefore, my proposal is a repertoire based on the Open Variation, that starting with 2.Nf3 and virtually always followed by 3.d4. I think it is only logical to devote our best studying efforts to a position that will probably arise quite frequently in our games, and to choose secondary lines against defences we won’t face so often. Vast practical experience also indicates that, against the Sicilian, the prospects of an advantage with other moves than 2.Nf3 are not great. Flexibility and the surprise factor is one thing, and basing our repertoire on harmless lines is a quite different one. My general philosophy for developing an opening repertoire is based on the following approach: against main lines, play main lines; against secondary lines, play secondary lines; against unsound lines, play the refutation. Some amateur players have asked me why, and I will try to state my case now: – Main lines are usually the best and the most frequent in practice. Being the most frequent, it is worth being well prepared against them; being the best, we are not likely to find a way to an edge in secondary lines. – We won’t face secondary lines so often, therefore it is less profitable to spend a long time on them in our preparation. A further point is that we would run the risk of reaching a good position, but one in which our opponent has far clearer ideas. A secondary defence is much more likely to offer secondary lines with good prospects for an edge. – Finally, it is worth searching and finding a refutation against a weak system, since it will work forever. Besides, these defences will usually take us by surprise and we need a convincing preparation against them. Of course, this is a basic approach and must be adapted to each particular case. Quite frequently, main lines may become secondary and vice versa; even some unsound lines may be rehabilitated, though this is less likely to happen. A flexible approach is always necessary. Our playing style must have its influence as well when it comes to building our repertoire. However, if our style does not involve an open game against the Sicilian, then we should consider whether 1.e4 is right as our first move after all. Although this book recommends main lines, from the point of view of the current state of chess theory, the repertoire we present also tries to fulfil the principles of economy and coherence, by choosing lines that can transpose into one another, whenever possible, or that share strategic ideas. Thus, there is one set-up which constitutes the core of this repertoire. It can be used (obviously, with important adjustments) against a wide range of variations (Najdorf, Scheveningen, Classical, Taimanov, Dragon, Kupreichik and some secondary lines). This set-up is based on the moves f2-f3, Be3, Qd2 and 0-0-0. I have always considered queenside castling in the Open Sicilian to be logical: the rook immediately occupies the only open file (for White). The position of the f-pawn allows some discussion. For many years, the general trend and almost a sacred rule was the idea that White cannot develop any active play against the Sicilian without the move f2-f4. Although well founded upon a wide experience, I have the feeling that this theory has been indiscriminately applied, thus leading White into trouble in several variations. The reason is that it fuels Black’s counterplay along the a8-h1 diagonal, with pressure on e4 and, from that weak point, on White’s position as a whole. In the f2-f3 set-up, the point e4 has a solid defence. There is no need for White to worry about this square, and his plan is clear-cut and easy to carry out. This might be, if not a theoretical, at least a practical reason why White’s results with this set-up have generally been so remarkable. Fischer’s comment that the Sicilian Dragon was a weak defence because an amateur as White could easily defeat a grandmaster with the Rauzer Attack, can be applied to a certain extent to other lines. About the structure of this book I have decided to present the book as a collection of annotated games, to make the material appear not too dull. Readers may use it as a reference book or read it from beginning to end, in order to become familiar with the most frequent tactical ideas, transpositions and strategic plans. A division has been made in four main Sections. The first contains minor second moves for Black after 2.Nf3, Section 2 deals with 4...e5, 4...g6 and 4...Nc6 systems after the exchange on d4, and in Sections 3 and 4, respectively the systems with 2...e6 and those with 2...d6 are discussed. Almost all systems have an individual chapter, though some have far less material. In my view, the current preparation and competition methods (I’m thinking especially about open and rapid chess tournaments) force us to possess an accurate knowledge of some specific refutations and favour the use of surprise variations. Many of these surprise weapons, despite their theoretical weakness, pose almost insurmountable complications in over-the-board play. Furthermore, my aim has been to provide the reader with a complete repertoire and therefore to answer clearly to the question of what to play in all reasonable positions. At the beginning and at the end of each chapter I have included short sections intended to make the study easier, but not strictly necessary for an experienced player. The chapters open with the title and the diagram reflecting the starting position of our study. In my opinion, there are a lot of underrated variations in the Sicilian (and a few, overrated). I have the feeling, reinforced by writing this book, that many are playable and pose problems for White, if the first player intends to achieve an edge. The introduction tries to guide the readers on the themes of the chosen line and its relationship with other variations. Here I feel obliged to mention the real father of the Sicilian Defence, Louis Paulsen (1833-1891). He was born in Germany but developed as a chess player in the United States. Paulsen investigated most of the important variations and understood the spirit of counterplay inherent in this defence. If the Sicilian wasn’t named after him, it was due to random circumstances. A deeper analysis of the ideas contained in every variation would have been interesting, but the book is already rather thick, so I considered it more important to go deeply into certain lines. This structure should altogether help black players to choose some lines for their repertoires, though in this case they must complete their study with the attacking lines for White that we don’t mention here. We have tried to present the material in a very clear way, without complex trees and with move-by-move explanations, with the exception of the more often repeated moves. We considered it very important to understand the position and to know the purpose of every move, in order to fix our memory and prevent our opening study from becoming useless, if we forget the lines after a few days or weeks. However, in some cases it has been impossible to avoid presenting a potentially disturbing branch. This book is a revised version of the Spanish original Desmontando la Siciliana. We can’t talk about a second edition, as most of the material has been changed rather than merely updated. Furthermore, some chapters are completely new, and in those which keep recommending the same lines, many model games are more recent and recommended subvariations have quite often changed as well. Nevertheless, we cannot talk about a new book either, since the structure and base material are the same. In some cases, I have changed my recommendations because some new lines are clearly better or have cast doubts on the old ones; at other times, the previously recommended line is still equally interesting and the reasons for the change are less conclusive. In those cases (and some others) I refer to the original text, identified with the abbreviation ‘DLS’. Of course, comparing both versions may be interesting for those who have the original book. Despite all the hours devoted to this work, I’m perfectly well aware that some variations will not resist the passing of time and I hope the readers will show their sympathy. I also encourage them to continue their research and complete their repertoires, when necessary, consulting other sources and analysing on their own. However, I hope the recommendations from this book can help the readers improve their repertoire, bring them some sporting pleasure and let them have a good time with the analysis of memorable games and interesting positions. Jesus de la Villa Garcia Pamplona, Spain, May 2009 Chapter 1 Second move sidelines 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 2.Nf3 is White’s most flexible move, as against many of Black’s strange second moves we’ll want to play 3.c3 and d2d4, which is not possible after 2.Nc3. A) 2...h6? 3.c3 e6 4.d4 d5 5.exd5 exd5 6.Bb5+ Nc6 7.Ne5 Bd7 8.Bxc6 bxc6 9.0-0± is a good example of how to deal with rare second moves, as is; B) 2...Qc7? 3.c3 Nf6 4.e5 Nd5 5.d4 cxd4 6.Na3! e6 7.Nb5 Qb6 8.Qxd4 Qxd4 9.Nfxd4² when the weak d6-square is a nuisance; C) 2...b6?! 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Bb7 5.Nc3 gives White a safe advantage with an English Attack set-up (Be3/f3/Qd2/0-00/g4) against almost anything Black tries. If White really wants to punish Black’s set-up though, De la Villa’s old recommendation 5...a6 (on 5...Nf6, 6.Bg5! is very strong, since taking on e4 loses to direct play, but 6...Nc6 7.Nf5± (Mekhitarian-Limp, Rio de Janeiro ch-BRA 2016) sets substantial problems for Black’s kingside development) 6.Bg5! remains very promising, e.g. 6...Qc7 7.Nd5! Qe5 8.Be3 Bxd5 9.exd5 Qxd5 10.Be2 e5 and now a recent improvement for White is 11.Nf5! Qxd1+ (11...Qe6 12.Bg4 Qc4 13.Bf3± doesn’t give Black time for ...d7-d5) 12.Rxd1 Nc6 13.0-0², which gave White more than enough compensation in Huschenbeth-Dann, Neustadt an der Weinstrasse 2017; D) 2...g6 3.d4 will transpose to a Dragon of some form after 3...cxd4 4.Nxd4. Instead 3...Bg7?! can be met with 4.c4 and a possible transposition to Maroczy Bind territory, but I particularly like 4.dxc5! Qa5+ 5.c3 Qxc5 (5...Nf6 can be met simply with 6.Be3!? Nxe4 7.Nbd2 Nxd2 8.Qxd2 for a pleasant lead in development) 6.Na3! when Black faces problems with his c5-queen in all lines: D1) 6...Bxc3+? 7.bxc3 Qxc3+ 8.Qd2 Qxa1 9.Nb5 Na6 10.Bc4 and e4-e5 gives White a crushing initiative, as the machine confirms; D2) 6...b6? 7.Be3 Qc6 8.Bc4+–; D3) 6...Qa5?! 7.e5! and Nc4 makes it very hard for Black to develop his pieces; D4) 6...d6 7.Nb5 a6 8.Be3 Qc6 9.Na7 Qc7 10.Nxc8 Qxc8 11.Qb3 gives White a very pleasant advantage with the bishop pair, especially if he piles up on f7 with his next moves: 11...Nf6 12.e5 dxe5?! (12...Ng4 13.Bc4 0-0 14.e6 f5 15.Bb6 a5 16.a4 splits Black’s position in two, but was a better choice) 13.Nxe5 0-0 14.Nxf7! Rxf7 15.Bc4 e6 16.Bxe6 Qc7 17.0-0-0 Nc6 18.Bb6 Qe7 19.Rhe1 Bh6+ 20.Kc2 with a decisive initiative for White; D5) 6...Nf6 7.Nb5! b6 (7...Nxe4? 8.Be3 Qc6 9.Nfd4 Bxd4 10.cxd4 followed by d4-d5 finishes Black; 7...Ng4 is only a one-move attack after 8.Nfd4!±; if 7...0-0 8.Be3 Qc6 9.Nfd4 Qxe4 10.Nc7 b6 11.Qf3!± refutes Black’s exchange sacrifice) 8.b4! Qc6 9.e5 Ne4 10.Nfd4 Qb7 11.Bd3 White has a monstrous initiative and has won nearly every game from this point. To avoid losing material to Qe2, Black should try 11...d5 12.exd6 0-0 when it might be most practical to return the pawn with 13.0-0!? Nxd6 14.Nxd6 exd6 15.Bf4 d5 16.Re1 Nc6 17.Nb5± as transpired in KhanSimmelink, email 2014; E) 2...a6!? This O’Kelly Variation might be the best of Black’s unusual second move tries. Now 3.Nc3!? is the most practical, as Black cannot reasonably avoid a transposition to our Open Sicilian repertoire: E1) 3...d6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 leaves Black nothing better than 5...Nf6 or 5...e6, transposing to other chapters; E2) 3...e6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 transposes to our Paulsen section; E3) 3...Nc6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 will transpose to a Taimanov after 5...e6. Instead 5...e5?! (5...d6 6.Be3 will also transpose to other variations of our repertoire) 6.Nf5! d6 7.Bc4ƒ is very passive for Black, as White dominates the key d5 hole; E4) 3...b5 4.d4 4...cxd4 (4...e6?! is a poor independent try in light of 5.d5 – the thematic reply when Black doesn’t trade on d4: 5...Bb7 6.Be2 Nf6 7.Bg5 h6 8.Bxf6 Qxf6 9.0-0² with a turbo-charged Benoni structure for White in Wei Yi-Yan Fang, Xinghua ch-CHN 2017. White will play e4-e5 against most moves, for a clear initiative) 5.Nxd4 Bb7!? (trying to be tricky with the move order, but it doesn’t change much. 5...e6 is a direct transposition to our Paulsen repertoire) 6.Bd3 (6.Bg5!?² might also be explored, by analogy to 2...b6) 6...d6 (6...Nc6 7.Nxc6 Bxc6 8.0-0 e6 brings us back to Paulsen theory; 6...g6 7.0-0 Bg7 8.Be3 d6 9.a4 b4 10.Nd5 Bxd5 11.exd5 Nf6 12.Be2!N is not one of the better versions of the Dragadorf for Black. Note that taking on d5 doesn’t save Black: 12...Nxd5 13.Nf5 gxf5 14.Qxd5 Nd7 15.Qxf5 Bxb2 16.Rad1 and Black’s king will never find safety) 7.0-0 Nf6 8.Qe2 e6 9.b4! This unusual resource works well, to stop ...b5-b4 in reply to a2-a4. 9...Qc7 (9...Be7 10.a4 bxa4 11.Nxa4 0-0 12.c4² is similar) 10.Bb2 Be7 11.a4 bxa4 12.Nxa4 0-0 13.c4 Nbd7 14.Nb3 White has a stable positional advantage as the a6-pawn is isolated and his space comes in pretty handy. The Nimzowitsch Variation 2...Nf6 This move defines the provocative Nimzowitsch Variation. 3.e5! The critical move. A straightforward option is the old recommendation 3.Nc3, which will almost certainly transpose to an Open Sicilian after 4.d4. The exception is if Black plays a quick ...d7-d5: 3...d5 4.exd5! Nxd5 5.Bb5+ Bd7 (5...Nc6 6.0-0 Nxc3 7.dxc3!?N 7...Qxd1 8.Rxd1 f6 9.Be3 e5 10.Nd2! gives White a nice queenside initiative with Nb3. Black suffers from poor development) 6.Ne5 Rakhmanov has done well from here as Black, but objectively White must have some edge: A) 6...e6 7.Nxd7 Nxd7 8.Nxd5 exd5 9.0-0² was Kovchan-Rakhmanov, Al-Ain 2015; B) 6...Bxb5 7.Qf3 f6 8.Nxb5 (threatening 9.Qxd5 and 10.Nc7+) 8...Na6 was De la Villa’s reason for rejecting this line, but computers show that Black’s sacrifice is unsound: 9.Qh5+ g6 10.Nxg6 hxg6 11.Qxh8 Qd7 12.Nc3 (12.Qh4!? Qxb5 13.c4 Qb4 14.a3 Qa4 15.b3 Qxb3 16.cxd5 is a safer route to an advantage) 12...Qe6+ 13.Kf1 Nab4 14.Qh4!± and thanks to Qa4/Qe4 ideas, White is safe, e.g. 14...Qa6+ 15.Kg1 0-0-0 16.Qg4+ f5 17.Qd1 Bg7 (Parligras-Westerberg, Reykjavik tt 2015) and now the greedy 18.Nxd5!N 18...Rxd5 19.d3 gives White a healthy material advantage. White will activate his h1-rook with a quick h4-h5; C) 6...Nf6 7.Qf3 Qc8 (7...Qc7 doesn’t threaten the knight after 8.0-0! as b7 and then a8 would be hanging: 8...a6 9.Bxd7+ Nbxd7 10.Nc4 Rc8 11.a4 and White got a stable positional advantage with d2-d3 and Bf4 in Külaots-Sikula, Hungary tt 2008/09) 8.a4! We reduce Black’s options by keeping the piece tension. 8...e6 (8...a6 as usual is a serious positional concession: 9.Bxd7+ Nbxd7 10.Nc4 e6 11.d3 Be7 12.0-0 0-0 13.Bf4 Ra7 (Antoli Royo-Rakhmanov, Figueres 2012) 14.a5 and Black has problems activating his pieces, especially the a7-rook) 9.b3!?N (the dark-squared bishop proves to be ideal on the long diagonal) 9...Bd6 (9...Nc6 10.Nxc6 Bxc6 11.0-0 Be7 12.Bb2 0-0 13.Bxc6 Qxc6 14.Qxc6 bxc6 15.d3²) 10.Bxd7+ Nbxd7 11.Nc4 Bb8 12.Qe2 0-0 13.Bb2 Qc6 14.0-0 White has a small edge (+0.24) but Black is quite solid. 3...Nd5 4.Nc3! This gives White a pleasant advantage without much workload. 4...Nxc3 4...e6 gives White a few shortcuts to a small edge, or he can study the main line for a slightly larger advantage: 5.Nxd5 (5.Ne4!? f5 6.Nc3 Nc6 7.Nxd5 exd5 8.d4 d6 9.Bf4 is a safe route to a small edge, as 5...f5 has severely weakened Black’s position) 5...exd5 6.d4 Nc6 (6...d6 7.Bb5+ Nc6 8.0-0 Be7 9.c4! gives White a strong initiative, as in the model game Jordan-Billaudelle, corr 2004) 7.dxc5! (7.c3 gives a smaller edge if White wants to play it safe) 7...Bxc5 8.Qxd5 A) 8...d6 9.exd6 Qb6 10.Qe4+ Be6 11.Qh4! Bxd6 12.Be2! (12.Bd3 Nb4 might give Black Marshall-like compensation with the bishop pair in an open position) 12...Bf5 13.c3 0-0 14.0-0 Rfe8 (14...Rae8 15.Qc4² consolidates the extra pawn to some extent) 15.Bc4 Bg6 16.Qg4 White is able to consolidate the extra pawn with moves like Bb3 and Be3, as 16...Re4? fails to 17.Bxf7+!, intending 18.Ng5+; B) 8...Qb6 is the trickier move, but objectively weaker if White replies energetically: 9.Bc4 Bxf2+ 10.Ke2 0-0 11.Rf1 Bc5 12.Ng5 Nd4+ (12...Nxe5 13.Nxf7! Nxf7 14.Rxf7 Qe6+ 15.Qxe6 dxe6 16.Rxf8+ Kxf8 17.Bf4 gave White a stable endgame advantage in many games, most notably Tan-Bach, Helsingor 2015) 13.Kd1 Ne6 14.Ne4 (White’s king looks unsafe on d1, but Black’s developing difficulties are more significant) 14...Be7 (14...d6 15.exd6 Rd8 16.Qh5 Bxd6 17.Bd3 gives White a very strong attack – indeed, he wins nearly every game from this position. Only 17...Bc7 18.Qxf7+ Kh8 seems to pose real practical problems, but 19.a4!± and following Mayorov-Meshalkin, corr 2013, will secure a clear advantage for White) 15.Nd6 Bxd6 16.exd6 and Black’s position is quite thankless with his queenside pieces currently trapped in. 5.dxc3 Nc6 6.Bf4 Qb6!? Black is provoking b2-b3 to discourage queenside castling by White 6...e6 7.Qd2 Qc7 8.h4 h6 9.h5! (fixing Black’s structure) 9...b6 10.c4 Bb7 11.0-0-0 0-0-0 12.Rh3 Ne7 13.Bd3² (Fenes-Dolgov, corr 2013) demonstrates White’s ideal set-up against normal play. Black struggles to develop his f8-bishop, as White is ready with Rg3. 7.b3 Qc7 7...h6 can also be met with 8.Bc4 e6 9.0-0 Qc7 10.Re1² Movsisyan-Martirosyan, Yerevan 2016. 8.Bc4 Now that b2-b3 has been played, castling queenside will run into counterplay with ...a7-a6/...b7-b5/...c5-c4, so we should switch to kingside castling. 8.Bd3 e6 9.0-0 may be even more accurate, with Ng5 in mind if Black tries to do without ...h7-h6. 8...e6 9.0-0 b6 10.Qd3 Bb7 11.Rad1 Be7 12.Rfe1² Black’s position is quite passive and ...h7-h6 can always be met with h2-h4. Summary of 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3: 2...h6 3.c3 – +0.40 2...Qc7 3.c3 – +0.50 2...b6 3.d4 – +0.50 2...g6 3.d4 Bg7 4.dxc5 – +0.50 2...a6 3.Nc3 – +0.40 if Black avoids Paulsen, Najdorf or Taimanov transpositions 2...Nf6 3.Nc3 d5 4.exd5 – +0.25 2...Nf6 3.e5 Nd5 4.Nc3: 4...e6 – +0.35 4...Nxc3 – +0.40 1.1 Alexander Panchenko 2495 Lev Psakhis 2480 Vilnius ch-URS U26 1978 (10) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 b6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Bb7 5.Nc3 d6?! 6.Bg5! 6.Bb5+!? Nd7 7.0-0 a6 8.Bxd7+ Qxd7 9.Nd5± is also unpleasant. 6...Nd7 7.Bc4 6...a6 was a better order for Black, as now 7.Ndb5!? Ngf6 8.Nd5 Bxd5 9.exd5 a6 10.Nd4± would leave Black’s light squares too weak. 7...a6 8.Qe2 b5 8...Ngf6 9.0-0-0 b5 10.Bb3 might already be close to winning for White with Rhe1 and e4-e5, e.g. 10...Qc7 11.f4 e6 12.Bxf6 Nxf6 13.e5 dxe5 14.fxe5 Nd7 15.Bxe6! and curtains. 9.Bd5 9.Bb3 is also good, as in the 8...Ngf6 note. 9...Qc8 c7 is a better square for the queen. 10.0-0 Ngf6 11.Rad1 11.Rfe1! e6 12.Nxe6! fxe6 13.Bxe6± is a slight refinement on the game. 11...e6 11...b4 12.Bxb7 Qxb7 13.Nd5 Nxd5 14.exd5 Qxd5 is too greedy after 15.Bh4! e5 16.f4±. 12.Nxe6! fxe6 13.Bxe6± Black is unable to develop his pieces in time. 13...Qc5 13...Be7 14.e5 Qc6 15.Nd5! Nxe5 16.Bxf6 gxf6 17.f4 Ng6 18.Nxf6+ Kd8 19.Nd5 gives White a nearly winning attack with f5-f6. 14.Nd5 Bxd5 15.exd5 0-0-0 15...Be7 16.Rfe1 0-0-0 17.a4! also keeps up the attack. 16.Rd3! Or 16.a4!. 16...Kb7 17.Rc3 Qd4 18.a4! Qe5 18...bxa4 19.Bxd7 Rxd7 20.Rc6+–; 18...Qxa4 19.Bxd7 Rxd7 20.Qe6+– 19.Be3 Nc5 19...Nxd5 20.Bxd5+ Qxd5 21.axb5 axb5 22.Rd1 Qf5 23.g4+– 20.axb5 a5 21.b6 Be7 22.Ra1 Ra8 Or 22...Nxe6 23.dxe6 Rc8 24.Rca3 Ra8 25.f4+–. 23.Qb5 Ra6 23...Nxd5 24.Rxc5! dxc5 25.Qd7+ Kxb6 26.Bxd5+– is a nice shot. 24.Qc6+ Kb8 25.Qc7+ Ka8 26.b7+! Nxb7 27.Qc8+ 1-0 1.2 Hikaru Nakamura 2613 Aleksander Wojtkiewicz 2536 New York 2005 (4) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 g6 3.d4 Bg7 4.dxc5 Qa5+ 5.c3 Qxc5 6.Na3 d6 7.Nb5 a6 8.Be3 Qc6 9.Na7 Qc7 10.Nxc8 Qxc8 11.Qb3 Nd7 Black selects this square to avoid 11...Nc6 12.Ng5 Nh6 13.h4! b5 14.h5 with a big attack. 12.Ng5 e6 12...Nh6 13.Be2 0-0 14.0-0 Nc5 15.Qd1 leaves Black’s knights looking silly. 13.Rd1 13.0-0-0! 13...Qc7?! Dubious, but 13...Nc5 14.Qa3 h6 15.Rxd6 Bf8 16.Nxf7! Kxf7 17.Bxc5 Bxd6 18.Bxd6± can hardly be called a sacrifice for White. 14.Bf4? 14.Bc4 h6 15.Nxf7! Kxf7 16.Bxe6+ Kf8 17.Bxd7 Qxd7 18.Bf4 and 19.Bxd6 is a hammer blow. 14...Be5 14...Nc5 15.Bxd6 Qxd6 16.Rxd6 Nxb3 17.axb3 h6 18.Nh3 Nf6 19.f3 Ke7 20.Rd1 b5² is also not so easy for White to convert to a win. 15.Be3 Nc5?! Better was 15...Ne7; 15...h6 allows a strong sacrifice on e6. 16.Bxc5 dxc5 17.Qa4+! Ke7? 17...Qc6 18.Qxc6+ bxc6 19.g3 is a very ugly endgame for Black, but far from lost. 18.Nxf7+– b5 19.Bxb5 axb5 20.Qxa8 Kxf7 21.Rd8 Black is unable to develop his kingside, so the game is decided. White won on the 49th move. 1.3 Wei Yi 2727 Yan Fang 2447 Xinghua ch-CHN 2017 (6) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.Nc3 a6 4.Be2 b5 5.d4 Bb7 6.d5 Nf6 7.Bg5 h6 8.Bxf6 Qxf6 9.0-0 d6?! This is asking for trouble. A) 9...e5 10.a4 b4 11.Nb1± and Nbd2-c4 is very passive for Black, So-Jiang, Montreal 2012; B) 9...Bd6 10.dxe6 Qxe6 11.a4 b4 12.Nd5 0-0 13.Re1± is also a positional wreck; C) 9...Qd8!? may be Black’s best chance, preparing ...Be7, but it’s a weird move and can be met in thematic fashion with 10.Qd3² and a2-a4 followed by bringing the knight to c4 in the worst case. 10.dxe6 fxe6 11.e5! dxe5 12.Nd2? 12.Nxe5! is a very powerful sacrifice: 12...Qxe5 13.Bh5+ Ke7 14.Re1 Qd6 15.Qg4 Nd7 16.Rad1 Qc6 17.Qh3! and the threat of 18.Bf3 compels Black to return his material with 17...Qxg2+ 18.Qxg2 Bxg2 19.Kxg2, but he still faces a strong initiative. 12...Nc6? 12...Qf7 13.a4 b4 14.Nce4 Be7 is not much for White, who is after all a pawn down. 13.a4! 0-0-0 A desperate attempt to develop that falls short. No better is 13...b4 14.Nce4 Qd8 15.Bh5+ Kd7 16.Qg4+–. 14.axb5 axb5 15.Bxb5 Nb4 16.Qe2 Be7 17.Nde4 Qg6 18.Ra7 Rd4 19.Rfa1 Rhd8 20.Rxb7 Kxb7 21.Ba6+ 1-0 1.4 Ladislav Fenes 2496 Igor Dolgov 2507 ICCF email 2013 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nf6 3.e5 Nd5 4.Nc3 Nxc3 5.dxc3 Nc6 6.Bf4 e6 7.Qd2 Qc7 8.h4 h6 9.h5 b6 10.c4 Bb7 11.0-0-0 0-0-0 12.Rh3 Ne7 13.Bd3² Rg8 13...Bxf3 14.Rxf3 Nc6 targets the e5-pawn, but after 15.Qc3 Nd4 16.Rg3 f6 17.Rg6! fxe5 18.Bg3 White severely binds Black up. 14.Qe3 Kb8 15.Bh7 Rh8 16.Be4 Nc8 In principle, we should keep the queens on: 16...Bxe4 17.Qxe4 Qb7 18.Qe2!ƒ and White can switch his focus to the d7pawn. 17.Bh2!? A somewhat mysterious move. 17.Rhh1 d5 18.exd6 Bxd6 19.Bxd6 Nxd6 20.Bxb7 Nxb7 is very solid for Black, but 17.Kb1 d5 18.cxd5 exd5 19.Bd3² seems more human. 17...d5 18.cxd5 exd5 19.Bd3 Ka8 20.Kb1 c4?! This is a considerable positional concession, giving d4 to White’s pieces. 20...d4 21.Qf4 Bd5 works well if Black can play ...Be6 to blockade White’s majority, but 22.Be4! quashes that plan. 21.Be2 Bc5 22.Qd2 Bxf2 23.Nd4 Bxd4 24.Qxd4± The engine undervalues White’s dark-square domination and quick pressure on the f7-pawn. 24...Qe7 25.Bg4 Rhf8 26.Rf3 Qe8 27.Bg1 Qb5 28.Qc3 Qc6 29.Rf4 White has manoeuvred such that he’s ready to pile up on the f7-pawn. Black tries to change the position, but the issue is that any opening of the play favours the white bishops. 29...d4?! 30.Bxd4 Qxg2 31.Rg1 Qh2 32.Rff1 By this stage Black has problems with his vulnerable queen and overall coordination. He is probably objectively lost (10, 72). Chapter 2 2...Nc6 sidelines 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 The most critical move, defining the Open Sicilian. 3...cxd4 4.Nxd4 Qb6!? The Grivas Variation. Instead: A) 4...Nxd4? 5.Qxd4 only activates White’s queen, and he can play common sense moves for an edge, e.g. 5...e6 6.Nc3 Ne7 7.Nb5 (or 7.Bf4 Nc6 8.Qd2±) 7...Nc6 8.Nd6+ Bxd6 9.Qxd6 Qe7 10.Qxe7+ Kxe7 11.Be3 with an obvious endgame advantage in Hase-Khrenov, email 1999; B) 4...d5? 5.exd5 Qxd5 6.Be3! gives White an ideal version of this structure as Nc3 will gain more time on Black’s queen. 6...e6 (Negi’s main line runs 6...Nf6 7.Nc3 Qa5 followed by dynamic play with 8.Qf3 and 9.0-0-0. More positional players might consider 8.Nxc6!? bxc6 9.Qf3 Bd7 10.0-0-0 with an equally substantial advantage) 7.Nc3 Bb4 8.Qg4 Qe5 9.0-0-0 Bxc3 10.bxc3 Nge7 Here it is hard to better Negi’s advised 11.Bf4 Qf6 12.Nxc6!± followed by Bd6, where the bishop is a monster; C) 4...Qc7 5.Nc3 e6 transposes to the Taimanov; D) 4...d6 5.c4! is likely to transpose to the Accelerated Dragon version of the Maroczy Bind after ...g7-g6. Instead 5...Nf6 6.Nc3 e6 7.Be2 Be7 8.0-0 0-0 9.Be3 gives White a highly favourable version of the Hedgehog, as Black’s knight on c6 stops him fianchettoing his c8-bishop (for this reason, the knight belongs on d7 in this structure). Games such as Rublevsky-Bryzgalin, Internet 2006, and Kabanov-Rodin, Olginka 2011, show how White can press his advantage on the queenside with Rc1/f2-f3/a2-a3/b2-b4; E) 4...Nf6 5.Nc3 g6?! (Black is trying to move order us out of the Maroczy Bind, but he allows something worse. 5...Qb6? has been refuted by the gambit 6.Be3! Qxb2? 7.Ndb5 Qb4 8.Bd2! and Black is lost, e.g. 8...Kd8 (or 8...Rb8 9.Rb1 Qa5 10.e5! Nxe5 11.Qe2 d6 12.f4 Bg4 13.Qe3+– as given in the previous edition) 9.Rb1 Qc5 10.Nd5! and Be3 will finish Black) 6.Nxc6! bxc6 (De la Villa’s indicated best line remains true today: 6...dxc6 7.Qxd8+ Kxd8 8.Bc4 Ke8 9.e5 Nd7 10.e6 fxe6 11.Bxe6 Nc5 12.Bxc8 Rxc8 13.Be3²) 7.e5 Ng8 8.Bc4 Bg7 9.Qf3 (or 9.Bf4) 9...f5 10.Bf4± The engine is already giving a +0.9 advantage if White charges his h-pawn shortly, such as with 10...e6 11.0-0-0 Qc7 12.h4! Nh6 13.h5ƒ – Black’s development is simply not present. With the Grivas Variation, Black wants to play a Scheveningen set-up only after kicking White’s knight back to b3. 5.Nb3 Nf6 6.Nc3 e6 7.a3! Despite not being popular anymore, this old recommendation still looks good for an edge. 7.Be3 Qc7 8.f4 Bb4! 9.Bd3 Bxc3+ 10.bxc3 d6= demonstrates why we should start with a2-a3. 7...Qc7 Black will play this move at some point as the queen blocks ...a7-a6/...b7-b5 and tends to get hit by Be3 at some point. A) If 7...a6 8.Bf4! is the best version of De la Villa’s original Bf4 interpretation, as now ...a7-a6 doesn’t entirely fit (8.Be3 Qc7 9.f4 d6 transposing to 7...Qc7 is also good): 8...Ne7 (8...e5 9.Be3 Qc7 10.g4! h6 11.h4 d6 12.Rg1 Be6 13.g5 hxg5 14.hxg5 Nd7 15.Nd5 Bxd5 16.Qxd5± was a turbo-charged English Attack for White in Ponkratov-Savitskiy, Moscow 2016) 9.Qd6 Qxd6 10.Bxd6 Nc6 (10...Ng6 11.Bg3 is similar) 11.Bf4! d5 (an unpleasant move, but otherwise 0-0-0 will fix the black d-pawn as a weakness) 12.exd5 (12.Na4!) 12...Nxd5 13.Nxd5 exd5 14.0-0-0 Be6 and in Kokarev-Akopian, St Petersburg 2013, the simple 15.g3 and Bg2 ties Black up to the weak IQP, with a clear positional advantage; B) 7...Be7 8.Be3! Qc7 9.f4 Now 9...d6 transposes to 7...Qc7, but 9...0-0!? is tricky, intending an 10.e5 Nd5! pawn sacrifice. It’s easier to avoid it with 10.Bd3 d6 11.g4! Nd7 12.g5 a6 13.h4 b5 14.Qd2 with a strong kingside attack. 8.Be3 8.f4 is very likely to transpose after 8...d6 9.Be3. The only extra option for Black is 8...d5 9.e5 Nd7, but 10.Nb5 Qd8 11.Be3 a6 12.N5d4² is an improved Steinitz French with his strong grip over the d4-outpost. 8...a6 8...d6 9.f4 Be7 is an improved Scheveningen for White as he normally doesn’t get in Be3/f2-f4 this easily. 10.Qf3 (an important preparatory move, as 10.g4 d5! is not completely clear) 10...a6 11.g4 Nd7 12.g5 b5 13.0-0-0 gives White a considerable initiative – compared to an English Attack, White has f2-f4/Qf3 instead of f2-f3. Slow play tends to get destroyed by f4-f5 or h2-h4-h5 and g5-g6, so Black should start counterplay with 13...Rb8! 14.Rg1 b4 15.axb4 Rxb4, but here too White’s attack is faster after 16.Qf2 Na5 17.Nd2 Qb7 18.b3 Qc7 19.Bd4². 9.f4 d6 10.g4! White treats the position like a Keres Attack. 10...b5 10...d5!? is a desperate bid for activity by the engine, but 11.Bg2 d4 (Black should accept a clear disadvantage by trading on e4) 12.Nxd4 Nxd4 13.Bxd4! Qxf4 14.e5 Nxg4?! 15.Rf1 Qg5 16.Ne4 Qg6 17.Qd2 and 0-0-0 gives White a devastating initiative. 10...Be7?! 11.g5 Nd7 12.h4± is an improved version of the 8...d6 note, as the queen can go to d2 instead of f3. 11.g5 Nd7 12.Qd2 12.h4 Rb8 13.Qe2 Be7 14.h5ƒ is another very promising set-up for White. 12.Qe2!? almost transposes to a variation of Negi’s repertoire – there he has 0-0-0 in place of a2-a3. But I think White’s play is simpler with the queen on d2. 12...Rb8 12...Nb6 13.Qf2 Rb8 14.0-0-0 Nc4?! 15.Bxc4 bxc4 16.Nd2± is in general an extremely safe structure for White’s king, as the b-file counterplay is easy to cover with a well-timed Bd4. 13.0-0-0 Be7 14.Kb1!? After this preparatory move, White is just about ready to play f4-f5 with a powerful attack. However, in view of Black’s option given in the next comment, 14.Nd4 or 14.Qf2 may be better. After the latter, there may follow 14...b4 15.axb4 Rxb4 16.Rg1, transposing to the favourable 8...d6 note. 14...Nb6 14...Nc5 offers Black more counterplay, although after 15.Nxc5 dxc5 16.f5 White’s position is preferable too. Now White has various good moves for an edge, but I like 15.Nd4!? to hold up Black’s ...b5-b4. 15...0-0 16.h4 Nxd4 17.Bxd4 Nc4 18.Bxc4 Qxc4?! 19.b3 Qc6 20.f5! This demonstrates that White’s attack strikes first, and is probably already winning. Summary 2...Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4: 4...d5 – +0.65 4...d6 – +0.35 4...Qb6 5.Nb3 Nf6 6.Nc3 e6 7.a3 – +0.35 2.1 Sergei Rublevsky 2687 Kirill Bryzgalin 2473 Internet 2006 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 2...Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 d6 5.c4 Nf6 6.Nc3 e6 would be the move order for our repertoire, though the Maroczy Bind position can arise from numerous move orders, where Black delays the move ...Nf6. 3.c4 Nc6 4.Nc3 d6 5.d4 cxd4 6.Nxd4 Nf6 7.Be2 Be7 8.0-0 0-0 9.Be3 a6 9...d5 10.exd5 exd5 11.Re1 dxc4 12.Nxc6 bxc6 13.Bxc4 is a risk-free edge for White. 10.Rc1 10...Nxd4!? A rare but sensible move, when we consider White’s thematic reply to the standard 10...Bd7. A) 10...Qc7?! gives White the tactical option of 11.Nd5!? exd5 12.cxd5 to regain the piece with interest: 12...Bd7 13.Re1!N 13...Nxe4 (it makes sense for Black to change the position, as the modest 13...Rfc8 14.dxc6 bxc6 15.Bf3 leaves the hanging pawns weak) 14.Qc2 Nc5 15.dxc6 bxc6 16.b4 Ne6 17.Bd3 g6 18.Nxc6 Bxc6 19.Qxc6 Qxc6 20.Rxc6±; B) 10...Bd7 11.Nb3! A thematic move to preserve the minor pieces while up in space, and preparing the dynamic f2-f4 set-up. 11...b6 (11...Re8 12.f4 e5 13.f5±) The engine is unable to show a constructive plan for Black, as reflected by its suggestion 12.f4 Qb8 13.g4 Bc8 14.g5 Nd7 (Pacher-Csolto, Slovakia tt 2014) and here 15.Qe1!± with ideas of Qg3 and f4-f5 is especially dangerous. 11.Bxd4 11.Qxd4 Bd7 12.Rfd1 would be a more aggressive set-up. 11...Bd7 11...b6 is the most flexible, but 12.f3 Bb7 13.b4² is a promising Hedgehog for Black. It’s a bit hard to appreciate, but the exchange of even one pair of knights deprives Black of much of the dynamism associated with his structure. 12.f3 12.Qd3 b5! gives Black some counterplay, so 12.a3 Bc6 13.Qd3 is probably the most controlling move order. 12...Bc6 12...b5 is the most active, but after 13.cxb5 axb5 14.Bxb5 Bxb5 15.Nxb5 e5 (15...Qa5 16.Nc3 d5 17.e5 Nd7 18.f4 doesn’t give Black enough counterplay for the pawn) 16.Be3 Rxa2 17.Qb3 Ra8 18.Na7! Nc6 gives White an initiative. 13.a3 13.b4 first would be slightly more precise, as ...d6-d5 is always met by exd5 and c4-c5, to keep the centre stable. 13...Qd7?! 13...Qb8 is a better place for the queen, restricting White’s advantage. 14.b4 b5 15.cxb5 axb5 16.a4! Black had probably just missed this trick. 16...bxa4 17.b5 Bb7 18.Nxa4± Bd8 18...Qd8 is almost too depressing to consider! 19.Nb6 19.Qb3!? also makes sense. 19...Bxb6 20.Bxb6 Rfc8 21.Qd2 e5 22.Rfd1 22.Bf2! is a better way to anticipate ...d6-d5, so that 22...d5 23.exd5 Nxd5 can be pinned down with 24.Bc4!±, forcing favourable exchanges sooner or later. 22...d5 23.exd5 Nxd5 24.Bf2 h6 24...Qe7!? 25.Bc4 25...Rxc4?! There are too many pieces left on the board for Black to reach a drawing endgame with all the pawns on one flank. 25...Rd8 26.Bg3 Qe6± was a sad necessity. 26.Rxc4 Qxb5 27.Rc5 Qb3 28.Qe1? The right move in principle, but it runs into some deep tactics. 28.Qc2 Qxc2 29.Rxc2 f6 was best, when the opposite-coloured bishops give White good winning chances, though I suspect Black is barely within the drawing margin with best play. 28...Ra2? 28...Nf4! 29.Rb1 Ne2+! 30.Kh1 (30.Kf1 Qd3 31.Rd1 Ng3+ 32.Kg1 Ne2+ is a perpetual) 30...Qxf3! 31.Rxb7 Qxf2! 32.Rc1 Qxe1+ 33.Rxe1 f6 is the rather sophisticated tactic Black needed to spot to save the game. 29.Rdc1?? 29.Rb1 Rb2 30.Rcc1 was the correct move order to consolidate. 29...Qb2? I assume the players were very short of time for these final moves. 29...Nf4! 30.R5c3 Qe6 is winning for Black, who is getting in ...Ne2, followed by ...e5-e4 to bring the bishop into the attack. 30.Rb1 Qa3 31.Rxb7 Ra1 32.Rb1 1-0 2.2 Torbjorn Ringdal Hansen 2473 Nicolaj Zadruzny 2251 Stockholm 2013 (1) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 g6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Nxc6 bxc6 7.e5 Ng8 7...Nh5 may be the best try, but 8.Bc4 Qa5 9.f4 Rb8 10.Bd2!± (Pecka-Ingersol, email 2013) is nonetheless quite depressing for Black. 8.Bc4 Bg7 9.Qf3 f5 10.Bf4 e6 10...Qa5 11.0-0-0 Bxe5 is a suicidal pawn grab without development: 12.Rhe1 Bxc3 13.bxc3 Nf6 14.Bd6 e6 15.Bxe6! dxe6 16.Qxc6+ Kf7 17.Qxa8+– 11.0-0-0 Qc7 12.h4! Once again, we can ignore 12...Bxe5 due to the thematic Bxe6 breakthrough. 12...Nh6 13.h5 g5 13...Nf7 14.hxg6 hxg6 15.Qg3± crashes through the kingside, but trying to close it up is only a band-aid measure. 14.Bxg5 Nf7 15.Bf4 Bxe5 16.Bxe5 Qxe5?! 16...Nxe5 17.Qg3 Qb8 is more tenacious, but 18.Bb3 Nf7 19.f4 led to a white win in Pommrich-Gaboleiro, email 2012, as Black has minimal development and an exposed king. 17.Bxe6! This breakthrough is the main one to remember in our variation, as Black needs to eliminate our e5-pawn to have any hope of freeing his pieces. 17...Qxe6 18.Rhe1 Ne5 19.Qe3 Or 19.Qg3!. 19...d6 20.f4 Kf7 21.fxe5 dxe5 22.Qxe5 22.g4! was more crushing, but the endgame is also a clinical win. 22...Qxe5 23.Rxe5 Re8 24.Rxe8 1-0 2.3 Dmitry Kokarev 2611 Vladimir Akopian 2684 St Petersburg 2013 (6) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Qb6 5.Nb3 e6 6.Nc3 a6?! 6...Nf6 7.a3 a6?! 8.Bf4 would be the normal move order – as a rule of thumb, an early ...a7-a6 is well met by Bf4 to exploit the weakened dark squares. 7.Bf4! Nf6 8.a3 Ne7 9.Qd6 Qxd6 10.Bxd6 Nc6 11.Bf4 d5 12.exd5 Nxd5 13.Nxd5 exd5 14.0-0-0 Be6 15.Be3 15.g3! 0-0-0 16.Bg2 Be7 17.Rhe1 Rhe8 18.Kb1± followed by doubling on the d-file represents the ideal piece placement. However, Black’s weak structure allows White to keep a long-term advantage in any instance. 15...Be7 15...Bd6 16.Be2 0-0-0 17.Rhe1 Rhe8 18.Bf3ƒ resembles the 15.g3 note. 16.g3 16.Be2 was better. 16...Bg4! A move earlier, White could have covered f3 with Rd3, but now this is marginally irritating. 17.Re1 0-0-0 18.Bb6 Rd6 19.Bc5 Re6 20.Bg2 Re8! Black rightly sacrifices his weak pawn for some activity. 21.Bxd5 Bg5+ 22.Be3 Bxe3+ 23.Rxe3 Rxe3 24.fxe3 Rxe3 25.Bxf7 Re2 25...Kc7² and ...h7-h6 leaves Black’s position devoid of weaknesses, so he is in reach of a half point. 26.Bc4! Rf2?! The rook should have moved to g2, as now Nd2-e4 comes with tempo. 27.Nd2 Nd4 28.c3 Ne2+?! The knight is stuck here, however 28...Nc6 29.Ne4 Rf8 30.Rf1 Rxf1+ 31.Bxf1 feels like a technically winning endgame. 29.Kc2 b5 30.Bd3 30.Bd5! Bf5+ 31.Kd1 Bg4 32.Ke1+– is the clearest way to exploit the awkward e2-knight. 30...h5 31.Be4 h4?! A desperate attempt to free the knight, but then two extra pawns will suffice for the win. Surprisingly, after the more patient 31...g5 32.Kd3 h4 33.Ke3 hxg3 34.hxg3 Rf6 there is no way to win the e2-knight by force, though 35.Rf1! should still be quite close to winning. 32.gxh4 Bh5 33.Kd3 Rf4 34.Ke3 Rxh4 35.Nf3 Bxf3 36.Bxf3 Nf4 37.Rg1 Ne6 38.Rg6 Nc7 39.Bg4+ Kb7 40.h3 Nd5+ 41.Ke4 Black resigned. 2.4 Stanimir Stanojevic 2381 Michal Tochacek 2560 ICCF email 2012 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Qb6 5.Nb3 Nf6 6.Nc3 e6 7.a3 Be7 8.Be3 Qc7 9.f4 d6 10.Qf3 a6 Since Black has played ...Be7 already, he has lost a significant tempo for accelerating his queenside play. 11.0-0-0 11.g4 was my recommendation, but transpositions are very likely. 11...b5 12.g4 Nd7 13.g5 0-0?! The game is a suitable warning of how easily things can go wrong if one tries to get by with ‘happy moves’ against our repertoire. 13...Rb8! 14.Qf2! A nice prophylactic move, preparing f4-f5 without allowing ...Nde5 with tempo. 14...Nc5 15.f5 Nxb3+ 16.cxb3 f6 It’s understandable that Black didn’t want to permit 16...Bd8 17.f6 when the f6-pawn prevents Black’s pieces coming to the defence of the king. 17.g6 h6 18.Kb1 Now it’s simply a matter of technique – White will prepare a Bxh6 breakthrough. 18...Rb8 19.Bh3! 19.b4, to stop all counterplay, might be played in an over-the-board game, but of course in correspondence there is time to work out a concrete solution in full. 19...b4 20.axb4 exf5 21.Nd5 Qb7 22.Rc1 Bd8 23.Qh4 Re8 23...Nxb4 24.Rxc8! Qxc8 25.Rc1 Qb7 26.Rc7! Bxc7 27.Bxh6 crashes through for what’s already a forced mate. 24.Bxh6! gxh6 25.Rxc6 Qxc6 26.Rc1 Qd7 27.Bxf5 Qg7 28.Bxc8 White has a huge attack at no material expense. He won on move 51. Chapter 3 The Lowenthal & the Kalashnikov 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 e5 5.Nb5 We already saw in the previous chapter how Black can struggle against White’s central space advantage in the Open Sicilian. With 4...e5 he occupies the centre at the price of weakening the d5- and d6-squares. White’s adequate reaction is 5.Nb5!, after which Black has a choice between 5...a6 (the Lowenthal Variation) and 5...d6 (the Kalashnikov Variation). The Lowenthal 5...a6?! 6.Nd6+ Bxd6 7.Qxd6 This gives White a pleasant advantage with the bishop pair. 7...Qe7 This has established itself as the main trend, leaving the f6-square for the knight in case White spurns the queen trade. The alternative is 7...Qf6 8.Qd1! Qg6 9.Nc3, and now: A) 9...Nf6 10.Qd6!± should not be allowed; B) 9...Nge7 can be cleverly met with 10.Be3!? to dodge Black’s ...d7-d5 gambit: 10...d5 (10...d6 is too passive after 11.h4! h5 12.Qd2± when Black has trouble finding a decent place for his king, and ...Be6 naturally sheds the d6-pawn; 10...f5?! 11.Nd5! Nxd5 12.Qxd5± is even worse) 11.exd5 Nb4 12.Bd3 Nxd3+ (12...Bf5 13.Bxf5 Nxf5 14.Bc5 Qxg2 15.Rf1 is losing for Black, as he either loses the b4-knight or gets hit by 15...a5 16.Qe2 0-0-0 17.0-0-0 when Black’s king is miles too exposed) 13.Qxd3 Qxd3 (13...Bf5 14.Qd2 Qxg2 (14...Bxc2 15.0-0 is already lost for Black, as the d- pawn is far too strong) 15.0-0-0 Ng6 16.Rhg1! Qxh2 17.d6± As before, the passed d-pawn is going to cost Black material eventually, and he lacks coordination to create counterplay) 14.cxd3 White has a safe extra pawn and with his pieces better organised to start, he has very decent winning chances. 14...Bf5 (if 14...b5 15.d6 Nf5 16.Bc5 also retains the extra pawn) 15.Bb6! If Black doesn’t take on d3, White will play Rd1, f2-f3 and eventually d3-d4 to trade his extra doubled pawn, but 15...Bxd3 16.0-0-0 Bf5 17.d6 Nc6 18.Nd5± turned the passed d-pawn into a powerhouse in Shishkov-Bohak, email 2013; C) 9...d5! has the best chance of confounding White: 10.Nxd5 Qxe4+ 11.Be3 Nd4 12.Nc7+ Ke7 There follows a very forcing line where not much has changed since 2009: 13.Rc1! Bg4 14.Qd3 Qxd3 15.Bxd3 Rd8 16.h3 Bh5 17.f4 Kd6 18.Nxa6 bxa6 19.g4 Bg6 20.f5 White regains the piece with a nice initiative due to the bishop pair and Black’s open king. For example: C1) 20...Ne7 21.fxg6 hxg6 22.c3 Nd5 23.Bxd4 exd4 24.cxd4² as in Reis-Salcedo Medero, email 2008; C2) 20...Nf6 21.c3 Nxf5 22.gxf5 Kc7 23.Bc2 Bh5 24.c4² Fetisov-Sikorsky, email 2008, though Black eventually held the draw; C3) 20...Bxf5 21.gxf5 Ne7 White has a few good options here. The easiest is 22.Bxd4!? exd4 23.Kd2 with an edge for White, as in Sochor-Salcedo Medero, email 2008. 8.Qd1! Once again, De la Villa’s recommendation stands the test of time. 8...Nf6 9.Nc3 Here Black has several options, some of which are surprising: 9...d6 A) 9...Nd4 10.Be3 0-0 is a tricky pawn sac White can just ignore for a safe edge: 11.Bd3!²; B) 9...0-0 10.Bg5 Qe6 11.Bd3 h6 12.Bh4 makes it hard for Black to get in ...d7-d5, e.g. 12...Ne7 13.Qf3! and Black remains under pressure; C) The surprisingly common 9...h6?! 10.Be3 d6?! (but allowing Qd2 and 0-0-0 with a clamp on d6 would be pretty depressing too) 11.Qd2 Be6 12.0-0-0 Rd8 13.Bb6 Rd7 14.Nd5 Bxd5 15.exd5 Nb8 16.g3 is a quite hilarious sequence where Black is unable to move his d7-rook or b8-knight, leaving him helpless to White’s ideas. 10.Bg5! Be6 11.Nd5 Bxd5 12.exd5 Nb8 13.c4 Nbd7 14.Be2 0-0 15.0-0 De la Villa stops here, but this position has been seen in many games, so let’s have a look at White’s basic set-up: 15...h6 16.Be3 Nh7 17.f3 f5 18.Rc1 Nhf6 19.b4 f4 20.Bf2 a5 21.a3 e4 22.fxe4 Nxe4 23.Bd4 axb4 24.axb4± The position has opened for White’s bishops, but slower play would have given White time to achieve the key c4-c5 break. This position arose in the model game Shailesh-Belous, Bhubaneswar 2016. Summary 2...Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 e5 5.Nb5 a6 6.Nd6 Bxd6 7.Qxd6: 7...Qe7 8.Qd1 – +0.50 7...Qf6 8.Qd1 – +0.35 3.1 Pavel Simacek 2471 Vojtech Zwardon 2413 Czechia tt 2016/17 (10) 1.Nf3 c5 2.e4 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 e5 5.Nb5 a6 6.Nd6+ Bxd6 7.Qxd6 Qe7 8.Qd1 Nf6 9.Nc3 d6 10.Bg5 Be6 11.Nd5 Bxd5 12.exd5 Nb8 13.Be2 13.a4 h6 14.Be3 Nbd7 15.Be2 0-0 16.0-0 should also be a little better for White, but I want to avoid 16...a5!?² after which it’s not that easy to open the queenside. 13...0-0 14.0-0 a5 14...Nbd7 15.c4 a5 16.b3! Nc5 17.Qc2 h6 18.Be3 Nfd7 19.Qf5!ƒ disrupts Black’s kingside play for a serious advantage. Once the kingside is under control, White can switch to the a2-a3/b2-b4 plan. 15.c4 h6 16.Be3 Nfd7?! 16...Nbd7 is better, though White can continually improve his position, starting with 17.Re1 Rfc8 18.Bd3². 17.Rc1 Na6 18.a3! Now 18...Nac5 runs into 19.b4, but otherwise the knight is misplaced on a6. 18...f5 19.f3 Ndc5 20.b3± Because White possesses the bishop pair, the opening of the centre favours him. 20...f4 21.Bf2 Qg5 22.Bxc5!? 22.Rb1 is more natural, but transforming the position also retains White’s substantial advantage. 22...Nxc5 23.b4 axb4 24.axb4 Nd7 25.c5! White is generally much better when he achieves this pawn break, and even more so if the pawn gets to c6. 25...e4 26.c6! Ne5 27.cxb7 exf3 28.Bxf3 Ra7 29.Rc7 Qd8 30.Qc1 Ra1? This makes White’s conversion task easy, but even the obligatory 30...Qb8 31.Rc8 Qxb7 32.Rxf8+ Kxf8 33.Qxf4+ Kg8 34.Be4 leaves Black struggling for a draw, down a pawn for nothing. 31.Rxg7+ Kxg7 32.Qxa1+– Qb6+ 33.Kh1 Qxb7 34.Qd4 Qb5 35.Kg1 Qd3 36.Qxd3 Nxd3 37.b5 Nc5 38.Bg4 Rb8 39.Rxf4 Rxb5 40.h3 Nd3 41.Rd4 Ne5 42.Be6 And White converted his advantage to a win on the 66th move. 3.2 Aleksei Voll 2561 Jens Andersen 2130 ICCF email 2008 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 e5 5.Nb5 a6 6.Nd6+ Bxd6 7.Qxd6 Qf6 8.Qd1 Qg6 9.Nc3 d5 10.Nxd5 Qxe4+ 11.Be3 11...Nd4 If 11...Nb4?? 12.Nc7+ Ke7 13.Bd3 Nxd3+ 14.Qxd3 Qxd3 15.cxd3 Rb8 16.Ba7 wins the rook. 12.Nc7+ Ke7 13.Rc1 Bg4 13...Rb8? 14.c3+– 14.Qd3 Qxd3 15.Bxd3 Rd8 16.h3 Bh5 16...Bc8 17.f4 exf4 18.Bxf4 Ne6 19.Nxe6 Bxe6 20.0-0 has scored well for White over several games. I’ll just note that on 20...Bxa2!?, the best reply is 21.Rcd1! Be6 22.Be4 Rxd1 23.Rxd1 Bc8 24.Bd6+ Ke6 25.Bf8!± and Black was unable to retain his extra pawn. 17.f4 Kd6 18.Nxa6 bxa6 19.g4 Bg6 20.f5 Bxf5 21.gxf5 Ne7 22.Rd1! 22.0-0 Nd5 23.Bd2 e4 24.Bxe4 Ne2+ 25.Kf2 Nxc1 26.Rxc1 Rhe8 27.Kf3 Nf6 was Ganguly-Gillani, Dhaka Zonal 2007, from the previous edition, but the engines show that after 28.Bf4+ Kc5! 29.Be3+ Kd6 White has nothing better than repeating moves, as 30.Bd3 Kc6 31.Bxa6 Ra8 32.Bc4 Nd7! gives Black an initiative for the material. 22...Kc7 23.0-0 It is not easy for Black to find compensation for White’s bishop pair, particularly in such an unbalanced pawn structure. 23...Rd6 23...f6 24.Rd2 Rd7 25.Be4 Rb8 26.c3 Nb5 is probably the most tenacious defence, but after 27.Rxd7+ Kxd7 28.Bc5! White is applying durable piece pressure, and has the more mobile pawn majority to boot – put that way, the engine’s assessment of ² even seems a bit modest. 24.Rde1!? White has a stable advantage, so we can afford to bide our time and consolidate the position. 24.c3 Ndxf5 25.Bc5 is the sharper alternative. 24...f6 25.c3 Ndc6 26.Be4 Nd5 27.Bc5 Rd7 28.Rf3 Nf4 29.Be3 Nd5 30.Bc1! The machine doesn’t think much of manoeuvring the bishop back, but it’s quite clever, as now with White’s pieces protected, Black’s knights struggle to handle the steady advance of White’s queenside pawns. 30...Nb6 31.Rg3 Nc4 32.Kf2 Rb8 33.b3 Nd6 34.Bb1 Rb5 35.Rg4!± Black could probably have defended better, but it’s easier to criticise his play than to give an improvement. In any case, White went on to win in instructive fashion. 35...e4 36.Bf4 Ne5 37.Bxe4! Ra5 37...Nxg4+ 38.hxg4 Rc5 39.c4 Kd8 40.Bd5± leaves the black rooks completely dominated by the bishops. 38.a4 Nxg4+ 39.hxg4 Rc5 40.c4 Kd8 41.Bd5 Nc8 42.Be6 Rd3 43.Rb1 g5 44.b4 Rc6 45.Be3 Nd6 46.c5 Ne4+ 47.Ke2 Ra3 48.Bd4 Rc7 49.Rd1 Ke7 50.Rd3 1-0 The Kalashnikov 5...d6 6.N1c3 This can transpose back to the Sveshnikov if Black plays an early ...Nf6. 6...a6 7.Na3 Be7!? This Libiszewski/Rotella recommendation has established itself as the main line, keeping Black’s options open. Let’s have a look at the alternatives: A) 7...Nf6 8.Nc4!² and Ne3 punishes Black’s inaccurate move order, though White could also transpose to the Sveshnikov with 8.Bg5. 8...b5 9.Ne3 Be7 would then be a funny transposition to our main line!; B) 7...Be6 has been played several times by Shirov, but it gives White time for 8.Nc4 b5 (8...Na5 was once tried by Harikrishna, but 9.Ne3 Nf6 10.Ned5 Nxd5 11.Nxd5 and Be3 is a depressing structure for Black) 9.Ne3 Nf6 10.g3 b4 (games such as Konovalov-Pogosyan, Rasskazovo 2016, demonstrate the positional issues with quieter alternatives for Black) 11.Ncd5 Nxe4 12.Bg2 f5 Now Negi gives the 13.a3 novelty, but it may be even more effective after flicking in 13.g4!? g6: 14.a3! bxa3 15.Rxa3± and with gxf5/Qh5 in the air, Black is struggling; C) 7...b5 is the old main line, but none of Black’s choices after 8.Nd5 are too convincing. Indeed, the last two repertoire books on the Kalashnikov advocated 7...Be7, since White is quick with c2-c4 in all lines: C1) 8...Nf6 9.c4 b4. Here, 10.Nxf6+ Qxf6 11.Nc2 Qg6 12.Qd5 (or the beautiful variation 12.Ne3 Be7 13.g3 Nd4 14.Bg2 Bb7 15.Nf5 Qxf5 16.exf5 Bxg2 17.Rg1 Bf3 18.Qd3 Be2 19.Qxd4 exd4 20.Kxe2 Rc8 21.b3 d5!=) 12...Bd7! 13.g3 Rc8 14.Bg2 Be7 15.b3 h5!? 16.h4 0-0 17.0-0 a5 gave Black standard counterplay for the structure in StrengellOzmen, email 2008. Therefore, Negi’s line 10.Nc2! is the way to go: 10...Nxe4 11.g3! The point of this Negi novelty is to play Bg2, 0-0 and a2-a3 for positional domination. 11...Rb8!? This preparation for ...Nc5 isn’t given by Negi, but White retains more than enough long-term compensation: 12.Bg2 Nc5 13.Be3 Be7 14.a3 b3 15.Ncb4 Na5 16.0-0 0-0 17.Qd2! and Black’s awkward piece placement ensures White’s edge; C2) 8...Nce7 9.c4 (9.Bg5!? also gives decent chances of an edge, but the strategy behind 9.c4 is easier to execute) 9...Nxd5 10.exd5 bxc4 11.Nxc4 Nf6 12.Be3 Rb8 13.Be2 Be7 14.a4 0-0 15.0-0² is a basic position where White scores very well – the engine undervalues White’s edge here as Black’s queenside pieces are stuck defending the structural holes. 15...Bb7 (otherwise Qd2/Na5-c6 is an issue. 15...a5? stops a4-a5, but the cure is worse than the disease after 16.Bd2! Ra8 17.Qe1 Bb7 18.Bxa5 Qb8 19.Nb6 Ra7 20.b4± Wastney-Nijman, Wellington 2016) 16.Nb6 Nd7 (KraftRawlings, email 2014, is a model example for White after 16...Qe8 17.a5 Bd8 18.Bc4²) 17.a5 f5 18.b4! This is even more pointed than Negi’s 18.Rc1. 18...f4 19.Nxd7 Qxd7 20.Ba7 Rbe8 21.Bb6 Bg5 22.Rc1ƒ and Black failed to create real counterplay in Welle-Istomin, email 2011; C3) 8...Nge7 9.c4 Nd4 (9...Nxd5 10.cxd5 Nd4 11.Be3 transposes) 10.Be3 (it’s much more practical to play for a positional edge than grab the b-pawn) 10...Nxd5 11.cxd5 and now: C31) 11...Be7 12.Bd3 0-0 13.0-0 Bd7 (13...Bf6 14.Qd2 leaves nothing better than transposing back with 14...Bd7, as 14...g6 15.f4!ƒ either destabilises the d4-knight after ...exf4, or White achieves a highly desirable f4-f5 break) 14.Qd2 Black has a few options, but a good model for White is Dominguez Perez-El Gindy, Tromsø 2013: 14...Rc8!? (14...Bf6 15.Rac1 is Negi’s main line, with the long-term plan of f2-f4, Bxd4 and bringing the knight to f3 to support a kingside push. But after 15...Qe7 16.f4 Rac8 17.Rxc8 Rxc8 it may be better to preserve the central tension with 18.Qf2!² as the knight on d4 is going nowhere) 15.f4 f5 This break gives the best chance of disrupting White’s strategic advantage, but 16.Bxd4 fxe4 17.Bxe4 exd4 18.Nc2 Bf6 19.Nb4 is still a long-term edge based on the light-squared domination expertly conveyed in Sprenger-Boguslavsky, Germany Bundesliga 2015/16; C32) 11...g6!? 12.Bd3 (12.Nc2 was the original recommendation, and while 12...Bg7! is a good pawn sacrifice that should transpose to our main line after 13.Bd3 0-0 14.0-0, I want to avoid Belous’s 12...Nxc2+ 13.Qxc2 f5! even though 14.exf5 Bxf5 15.Bd3 Rc8 16.Qd2 Qd7 17.0-0 Bg7 18.h3 0-0 19.Rfc1 retains a symbolic advantage) 12...Bg7 13.0-0 0-0 14.Nc2 This is covered in detail by Negi, and no games were played since, so I’ll give a condensed analysis: C321) 14...Kh8 15.f3!? f5 16.Nxd4 exd4 17.Bf2± is a very pleasant structure for White, who has good chances to collect the d4-pawn; C322) 14...Bd7 15.Nxd4 exd4 16.Bf4 Qb6 In Sari-Ozates, Canakkale 2016, White tried Negi’s novelty 17.g4 (aimed against ...f7-f5) but I’d prefer to build up slowly with 17.Rc1 Rac8 18.Rxc8 Rxc8 19.a3² when White can continue with moves like Qd2 and f2-f3; C323) 14...Nxc2 15.Qxc2 Bd7 16.Rfc1 Rc8 17.Qd2 f5 18.Qb4!N 18...f4 19.Rxc8 Bxc8 20.Bd2 Qb6 21.a4ƒ Negi gives the same plan, but with 16.Rac1, so in our version we have the rook on a1, where it is slightly better placed than on f1. 8.Nc4! The typical reply to a delayed ...b7-b5 – White readies all his minor pieces to control d5. 8...b5 9.Ne3 Nf6 10.g3! 10.Bd3 0-0 11.0-0 Rb8 12.a3 Nd4 13.a4!? (13.Ncd5 Ne6!= is a bit annoying, but with a2-a4 thrown in, a4-a5 proves strong) 13...b4 14.Ncd5 Nxd5 15.Nxd5 Bg5 16.Bxg5 Qxg5 17.a5² with a nice hold on the queenside is a decent alternative, but 10.g3 is more harmonious. 10...0-0 Now both sides continue with their thematic set-up. 10...h5 has fallen out of fashion because of model games like Istratescu-Ikonnikov, France tt 2007, but even here I have a new approach: 11.Ncd5!?N 11...h4 12.c3 (it’s hard to explain, but White seems to benefit from not committing his kingside when Black tries to play there) 12...Rb8 (12...Nxe4? 13.Bg2 f5 14.Qc2± regains the pawn with interest – Nxf5! is coming) 13.Qd3 b4 14.Be2!? Nxd5 15.Nxd5 bxc3 16.bxc3 hxg3 17.fxg3 Black has tried to play on both flanks, but the result is that he didn’t achieve much, and his struggles to complete development give White a pleasant advantage. 11.Bg2 b4 12.Ncd5 Nxd5 13.Nxd5 Bg5 14.Bxg5 Qxg5 15.0-0 Rb8! A pivotal move for meeting a2-a3 with ...a7-a5, and a key position for the variation. While the engines tend to give a stable +0.3 edge, Black’s position is solid and it’s not easy for White to transform it into something more tangible. Fortunately, I managed to find a small improvement over Rotella’s extensive analysis in The Killer Sicilian. 16.c3!? This is the positional approach, playing against Black’s queenside pawns, but the attacking alternative 16.Qd3 a5 17.f4 Qd8 18.f5 Kh8 19.f6 g6= seems less effective, as it’s hard to build up the kingside attack. 16...a5 16...bxc3 17.bxc3 Qd8 18.Qd3 Ne7 19.Ne3 Rb6 20.Rab1 Rc6 was Cipressi-Rotella, email 2010. Rotella points out that Black will be fine if he achieves ...Qc7/...Rc5/...Nc6 followed by ...Be6xd5, so we should play 21.Rfd1! Qc7 22.c4 Rd8 23.Qb3 to meet ...Rc5 with Qb6 and pressure the d-pawn. It’s holdable but quite passive for Black and we can set a few problems with a later f4-f5. 17.Qa4 Bd7 18.Rfd1 Qd8 19.Rd2 g6 20.Rc1 Kg7 21.Ne3 Qc7 (Leupold-Isigkeit, corr 2012) 22.Qd1! Black has defended the a5-pawn well, so we focus our attention on d6. 22...bxc3 23.bxc3 Be6 24.Bf1!² We should trade minor pieces to leave Black’s rooks more tied up to the d6-weakness. A good illustration of the plan is 24...Rfd8 25.Bc4 Na7 26.Bxe6 fxe6 27.h4!? when Black has a lot of weak pawns, making his position very unpleasant to play. Summary 5...d6 6.N1c3 a6 7.Na3: 7...Be6 8.Nc4 – +0.30 7...b5 8.Nd5 Nf6 – +0.30 7...b5 8.Nd5 Nce7 – +0.35 7...b5 8.Nd5 Nge7 – +0.30 7...Be7 8.Nc4 – +0.30 3.3 Nikolay Konovalov 2459 Georgy Pogosyan 2377 Rasskazovo 2016 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 e5 5.Nb5 d6 6.N1c3 a6 7.Na3 Be6 8.Nc4 b5 9.Ne3 Nf6 10.g3 Be7 11.Bg2 0-0 12.0-0² This position can arise from several move orders, in the event of Black developing his pieces automatically. 12...Rc8 12...Na5 13.b3! Nb7 14.Bd2ƒ puts the blot on the b7-knight, which may be kicked away with b2-b4 if ...Nc5. 13.Ncd5 13.a4! b4 14.Ncd5 is a better move order, as the queenside pawns will prove a target: 14...a5 (or 14...Bxd5 15.exd5 Nd4 16.Bd2 Rb8 17.c3 bxc3 18.Bxc3±) 15.Bd2 Nd7 16.h4 Nc5 17.c3 bxc3 18.bxc3 White has a clear advantage, as Rb1/Nc4 will tie Black up to defending the queenside. 13...Nd7 13...Na5! is well timed now, as Black now threatens to trade on d5 without White being able to keep a piece on the outpost. So, after 14.c3 Nc4 15.Nxf6+ Bxf6 16.Nd5 Bg5 17.Bxg5 Qxg5 18.b3 Na5 19.Rc1² Black would at least partially free his position in trading his passive bishop. 14.a4! Nb6?! Avoiding ...b5-b4 only allows White to favourably open the queenside and weaken Black’s structure. 15.axb5 axb5 16.h4!± Preventing the only active idea of ...Bg5. 16...Nd4 17.c3 Nc6 18.Nf5 18.Qd3! 18...Bxf5 19.Nxb6 Qxb6 20.exf5 Ra8 21.Rxa8 Rxa8 22.Be3 Qb7 23.f6! A nice tactical blow to finish Black’s defences. 23...Bxf6 24.Qxd6 Rc8 25.Ra1 Qb8 Otherwise Ra7 was strong. 26.Qxb8 Nxb8 27.Ra5+– White wins a pawn and, with the bishop pair and connected passers, the remainder was easy (1-0, 42). 3.4 Mikel Ochoa Aldaz 1731 Ainhoa Ortin Blanco 1992 Pamplona 2017 (1) Normally I don’t cover club players’ games in a repertoire book, but this one may give you, dear reader, the confidence and understanding to also play the opening like a super-GM! 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 e5 5.Nb5 d6 6.N1c3 a6 7.Na3 b5 8.Nd5 Nce7 9.Bg5!? 9...h6? This most common move is a severe mistake! Black needs to deal with the pin at the earliest opportunity. A) 9...f6!? is a good move, but it doesn’t fully equalise: 10.Be3 Nxd5 (10...Rb8 11.Nb4! f5 12.c4 gives White a promising initiative, based on 12...a5?! 13.c5!! axb4 14.Nxb5 Rxb5 15.Bxb5+ Bd7 16.Bxd7+ Qxd7 17.cxd6±) 11.Qxd5 Rb8 12.Qb3 Bb7 13.f3! (13.Bd3 d5 14.Rd1 Qa5+ 15.Bd2 Qa4 16.exd5 Qxb3 17.axb3 Bxd5 18.0-0 Ne7 19.Ra1 Kf7 20.Rfd1 Be6=) 13...d5 14.Rd1 White has the better chances, as reflected by the fact that the engine already wants to play 14...Qa5+ 15.Bd2 Qd8, which gives White time to gain a serious lead in development with 16.Be2²; B) 9...Rb8! 10.c4 h6 is an annoying (albeit almost unplayed) line that convinced me to recommend 9.c4: 11.Bd2 Nxd5 12.cxd5 Be7 13.Bd3 Bg5 (after this exchange of the dark-squared bishops, Black doesn’t experience any positional problems) 14.Nc2 Bxd2+ 15.Qxd2 Ne7 16.0-0 0-0= 10.Bxb5+! axb5 11.Nxb5 Ra7 11...Ra6 12.Ndc7+ Kd7 13.Bd2 is already winning for White, who has a vastly improved version of the 11.Bxb5 Sveshnikov sacrifice. 12.Nxa7 Qa5+ 12...hxg5 13.Nxc8 Qxc8 14.a4 Nxd5 15.Qxd5± gives White a slight material advantage, and a strong passed a-pawn. 13.c3! 13.Qd2 Qxa7 14.Be3, as in Feygin-Ivanov, Kharkov 1997, also favours White, but 13.c3 is even better. 13...Qxa7 14.Be3 Qb7 15.Nb6! Qxe4 15...Be6 16.Qa4+ Kd8 17.0-0-0 is a crushing initiative for White; 15...Qc6 16.Nxc8 Nxc8 is probably best, but White is on track to win after 17.Qd5!. 16.Qxd6 f6 17.Nxc8 Nxc8 18.Qe6+ 18.Qc7! 18...Nge7 19.0-0 Qd5 20.Qa6 Qc6 21.Qxc6+ Nxc6 22.a4+– With three connected passers, White should win without too much trouble. However, White lost his way and even the game (0-1, 52). 3.5 Leinier Dominguez Perez 2757 Essam El Gindy 2487 Tromsø 2013 (1) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 e5 5.Nb5 d6 6.N1c3 a6 7.Na3 b5 8.Nd5 Nge7 9.c4 Nd4 10.Bd3 Nxd5 11.cxd5 Be7 12.0-0 0-0 13.Be3 Bd7 14.Qd2 Qb8 I covered Black’s alternatives in the theoretical section. 15.f4 Bd8 15...Qb7 is the engine’s move, but it is a bit artificial and can be met in several ways. 16.Rac1 Rac8 17.Rxc8 Rxc8 18.Qf2² by analogy to the main game is one decent option. 16.Bxd4 exd4 17.Nc2 17...Bf6 The bishop struggles to find a good square in any case, but perhaps 17...Bb6 was a better try, to have the option of ...f7-f5 in some positions. 18.f5! f6 19.Ne1² is a good reply then, leaving Black without a pawn break as he waits for White to improve his position with Nf3, g2-g4 and so forth. 18.Rae1 18.Ne1 Qb6 19.Nf3² was Negi’s recommended plan, and indeed may be the strongest, but because the structure is fixed in White’s favour, White has some flexibility in how to press the advantage. 18...Re8 19.Qf2 Kh8 20.Kh1! White doesn’t want to take on d4 and free Black’s bishop, preferring to keep control. 20...Qb6 21.Re2 21.Qg3! first seems even more accurate. 21...Re7?! 21...g6² at least allows Black to reorganise his defences somewhat. 22.e5! 22.Nb4!? is also possible, in case White wants to continue improving his position. 22...dxe5 23.fxe5 Rxe5 24.Rxe5 Bxe5 25.Qxf7 Qd6 26.Qh5 h6 27.Ne1 27.Re1! Re8 28.Nxd4 wins a pawn. Perhaps Dominguez was reluctant to open the position for Black’s bishops, but Black is unable to exploit this. 27...Bf4 27...g5 28.Nf3 Rf8 29.Nxg5 Rxf1+ 30.Bxf1 Qf6 31.Nf3± leaves White a pawn up, but the open position gives some hopes for the bishop pair to hold the draw. 28.Nf3 28.Qf3! Re8 29.Nc2± 28...Rc8? 28...Rf8! 29.Nxd4 Rf6° would see Black coordinate his forces to obtain good compensation. 29.Nh4? 29.Qf7! Rf8 30.Ne5! is a beautiful, winning tactic. 29...Kg8 30.Nf5 Bxf5? 30...Qf6! 31.Qg4 g5² opens the king, but was the only way for Black to hang on. 31.Qxf5 Rf8 32.Qh7+ Kf7 Black resigned without waiting for 33.Qe4/33.g3. 3.6 Andrei Istratescu 2619 Vyacheslav Ikonnikov 2549 France tt 2007 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 e5 5.Nb5 d6 6.N1c3 a6 7.Na3 Be7 8.Nc4 b5 9.Ne3 Nf6 10.g3 h5 11.Bg2 h4 12.0-0 White has good chances for an advantage in this main line, as his strong grip over the centre makes Black’s flank play less effective. 12...Nd4?! The most common move, but it only helps White play his Ncd5/c2-c3 plan. A) 12...h3 13.Bh1 0-0 14.Ncd5 Nxd5 15.Nxd5 Bg5 is a thematic reply, but White can use Black’s advanced h-pawn to create attacking chances on the kingside: 16.f4!N 16...exf4 17.gxf4 Bh6 18.Qh5 Be6 19.c3 b4 20.Rf2 Bxd5 21.exd5 Na5 22.Be3 bxc3 23.bxc3 Qf6 24.Bd4 Qg6+ 25.Qxg6 fxg6 26.Be4 Rxf4 27.Rxf4 Bxf4 28.Bxg6 and White’s bishop pair gives him serious winning chances in this endgame; B) 12...Rb8 13.Ncd5 Nxd5 14.Nxd5 Be6 is Black’s most solid line, and far from easy to crack: 15.a4 (15.Be3!? is probably the route to a small edge) 15...b4 (15...bxa4! 16.Rxa4 a5 17.b3 Nb4 keeps White’s advantage to an absolute minimum) 16.Be3 a5 17.Qd3 Qd7 18.c4² White kept control of the play in Cleto-Minchev, email 2008. 13.Ncd5 Nxd5 14.Nxd5 Be6 15.c3 Bxd5 15...Nc6 16.a4! in turn places Black under substantial queenside pressure. 16.exd5 Nf5 17.a4! White is clearly for choice, with the bishop pair advantage, better structure and safer king – with ...h5-h4 played, ...0-0 is less appetising for Black. 17...Rb8 17...hxg3 18.fxg3! g6 19.Qd3 bxa4 20.Be4! keeps maximum pressure on Black, who struggles to coordinate his forces. 18.axb5 axb5 19.Qd3 19.Bh3! is a better way to target the knight, but Istratescu’s move is also good. 19...g6?! 19...Nh6 is ugly, but at least permits ...Bg5 in some positions. 20.g4! Ng7 21.f4 exf4 22.Bxf4 0-0 23.Ra6 Qc8 24.Ra7 Rb7 25.Rxb7 Qxb7 26.Qd4 26.Bd2!? 26...Rc8 26...f5 27.gxf5 Nxf5 28.Qe4 is also clearly in White’s favour, as Black’s king is a bit open. 27.h3 Ne8 28.Qf2 28.Bh6 might be even better, to tie up the e8-knight. 28...b4 29.cxb4 Bf6 30.Kh1 Qxb4? A blunder from the constant pressure, but even 30...Ra8 leaves Black in a much worse position after 31.Qd2ƒ. 31.Bg5!+– Rc2 32.Qf3 Rxg2 33.Kxg2 Qxb2+ 34.Kh1 And White won (44). Chapter 4 The Accelerated Dragon 4...g6 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 g6 The Accelerated Dragon can be a very tricky opening at the club level, as White must constantly watch out for ...d7-d5 in one go in the 5.Nc3 variation. Fortunately, it’s very hard for Black to mix up the game against my recommendation. 5.c4! The Maroczy Bind is easy to play – you place your minor pieces with Nc3/Be3/Be2/0-0, and usually Qd2/f2f3/Rac1/b2-b3/Rfd1 in some order from there. Alternatives to 5...Bg7 (Gurgenidze Variation) A) Tiviakov’s 5...Bh6 is a bit slow if White develops normally: 6.Bxh6 Nxh6 7.Nc3 0-0 8.Be2 d6 9.0-0 f6 10.Qd2 Nxd4 11.Qxd4 and Black’s set-up remains passive, while White can build up with b2-b4, f2-f4, Nd5 and Rad1; B) 5...d6 6.Nc3 will transpose to other lines; C) 5...Nf6 6.Nc3 d6 followed by 7...Nxd4, the Gurgenidze Variation, is probably Black’s best line as it leads more easily to simplifications (which favour the side with less space) (6...Nxd4 7.Qxd4 d6 8.Be3 Bg7 transposes after 9.Be2 or 9.f3): C1) 7.f3!? With this move order White can somewhat restrict Black’s options. 7...Nxd4 (7...Bg7 8.Be3 0-0 9.Be2 Nh5!? is permitted by the 7.f3 move order, however White has several decent options, my preference being 10.Nxc6 bxc6 11.Qd2 Nf6 (or 11...Qa5 12.0-0 Rb8 13.Rfc1!² with the idea of preparing the b2-b4 break with a2-a3) 12.0-0 Nd7 as in O’Hare-Reichenbach, email 2014, when a slight improvement is 13.Rad1 Qc7 14.b4 with a pleasant space advantage. White can play for c4-c5 to fix Black’s queenside) 8.Qxd4 Bg7 9.Be3 0-0 10.Qd2 a5 (10...Be6 11.Rc1 Qa5 12.b3 Rfc8 is usual, and transposes to line C2 after 13.Be2) With the pawn on f3, we don’t have to allow Black’s plan of ...a5-a4/...Qa5/...Be6/...Rfc8. 11.b3! a4 (11...Bd7 12.Be2 Bc6 13.0-0 Nd7² is the 5...Bg7 main line with an extra tempo for White; 11...Be6 12.Rb1 Nd7 13.Be2 Nc5 14.0-0ƒ on the other hand makes little sense for Black, as a2-a3 and b2-b4 will force his pieces back) 12.b4 Be6 13.Rc1 Nd7 14.Be2 Nb6 15.Nb5 a3 16.Nd4 Bd7 In Caruana-Carlsen, St Louis 2014, White achieved a strong attack with 17.h4!?, but the more positional 17.0-0 Na4 18.f4 also secures a stable advantage, as Black has some trouble coordinating his pieces around White’s space. However, 18...e5 may confuse things a little. Probably White’s strongest option is 17.Kf2, which is a fairly frequent idea in this line; C2) 7.Be2 Nxd4 (7...Bg7 8.Be3 transposes back to 5...Bg7) 8.Qxd4 Bg7 9.Be3 0-0 10.Qd2 Black will tend to play ...Be6/...Qa5/...Rfc8 to pressure our c-pawn, but White’s 60% score shows there’s no cookiecutter solution for Black: C21) 10...Ng4 tries to disrupt White’s set-up, but Black ends up losing some time: 11.Bg5 h6 12.Bf4 Kh7 13.0-0 Qa5 (13...Bd7 14.Nd5 Ne5 was played in two email games, but 15.Be3!² and f2-f4 is an improvement) 14.Rab1 Ne5 15.b4 Qd8 16.Be3 and Black remains passive – a common story against the Bind; C22) 10...Qa5 11.f3 Be6 12.Rc1 transposes to 10...Be6; C23) 10...a5!? is the main trend, but Caruana-Antipov, Gibraltar 2017, showed a nice idea for White: 11.f3 (we could also reach this position with the 7.f3 move order) 11...a4 12.Kf2! Qa5 (other moves are met in the same way) 13.Rac1 Be6 14.Nd5 Bxd5 15.Qxa5 Rxa5 16.cxd5 Compared to 11.0-0, White’s king is better placed on f2. Black probably has to try and change the position, but after 16...e6!N 17.dxe6 (17.Bf4 may also favour White, but it’s messy) 17...fxe6 18.Ke1 White has a fairly stable bishop pair edge and one less pawn island. Black can bid for counterplay, but 18...d5 19.e5 Nh5 20.Bd4ƒ followed by g2-g3 and f2-f4 keeps control; C24) 10...Be6 11.Rc1 Qa5 12.f3 Rfc8 (12...a6 can be met with the usual 13.b3, but even better is 13.Nd5! Qxd2+ 14.Kxd2 Bxd5 15.cxd5 as in Dvoirys-Tiviakov, Podolsk 1993. Black faces a long fight for a draw after b2-b4 and a4a5, and if White gets his bishop to h3, Black will lose the c-file for sure) 13.b3 and now: C241) 13...Rab8!? is Zvjaginsev’s preference, but White has a couple of routes to an edge: 14.g4!? (the dynamic choice, whereas 14.Na4 Qxd2+ 15.Kxd2 gave a small positional advantage in Yu-Zvjaginsev, China tt 2017; 14.Nd5 also offers a small but nice advantage after 14...Qxd2+ 15.Kxd2 Nxd5 16.cxd5 Bd7 17.g4) 14...a6 Now 15.Na4 Qxd2 16.Kxd2 gives us a good version of 13...a6, but I also like 15.g5!N 15...Nd7 (15...Nh5 16.f4 f5 17.Nd5 Qxd2+ 18.Kxd2 is an ugly position for Black) 16.Nd5 Qxd2+ 17.Kxd2 Bxd5 18.cxd5 followed by h4-h5, with an obvious positional advantage; C242) 13...a6 14.Na4 Qxd2+ 15.Kxd2 Nd7 (more cumbersome is 15...Rc6 16.Nb6 Re8 17.g4 Nd7 18.Nd5²) 16.g4² This is to some extent the key position for the Gurgenidze Variation. Black’s problem is that his winning chances primarily lie in White over-pressing or wasting multiple tempi, and in general it is quite difficult for human players to play purely reactive chess in the hope of a draw. 16...f5 (16...Rc6 should be met with the incisive 17.h4!, when games such as Brunsek-Benko, corr 2005, and BazantovaPino Munoz, corr 2012, demonstrate that passive play by itself will not suffice for a draw. Naturally, if 17...Nc5 White should keep the minor pieces when he has more space: 18.Nc3!²) 17.exf5 gxf5 18.h3! Rf8 19.f4 Rad8 (19...Nf6 20.Rhg1 Rad8 21.Bb6!ƒ and Bf3 is best avoided; 19...d5!? is one attempt to liquidate everything for a draw, but in the forcing line 20.cxd5 Bxd5 21.Rhd1 Rac8 22.gxf5 b5 23.Nc5!N 23...Nxc5 24.Bxc5 Bb2 25.Rc2 Be4 26.Bd3 Bxd3 27.Kxd3 Rcd8+ 28.Ke2 Rxd1 29.Kxd1 Rxf5 30.Bxe7 Bf6 31.Bd6 Rd5+ 32.Rd2 Rh5 33.Rd3² Black remains a pawn down and doesn’t have an easy draw by any means) 20.Nc3 (following Sevian-Banawa, St Louis 2015, with 20.g5!? Bf7 21.Bf3 is also possible, accepting a smaller advantage but also avoiding positions where Black might memorise the drawing method at home) 20...d5! 21.cxd5 Nf6 22.Bb6 Nxd5 23.Bxd8 Rxd8 24.Nxd5 Bxd5 25.Rh2 Bxb3+ (or 25...Bb2 26.Rc7 Bd4 27.Bd3!? Bb6 28.Rc3 Ba5 29.Kc2 Bxc3 30.Kxc3 and Black can’t avoid losing a kingside pawn, because of 30...Be4?! 31.Bxe4 fxe4 32.Rd2!) 26.Ke1 Bxa2 27.Bxa6 bxa6 28.Rxa2 Rd4 Guseinov has held this position on two occasions, but neither of his opponents kept the pawns on with 29.Rf2!, which still requires some accuracy from Black to hold the draw. Old main line 5...Bg7 5...Bg7 6.Be3 6...Nf6 A) 6...Nh6 7.h3!², as in two Roiz-Shukh games, leaves the knight out of play on h6; B) 6...Qb6 7.Nb3 Qd8 is a strange preference of Mamedov, which is well met by 8.Nc3! Bxc3+ 9.bxc3 Nf6 10.f3 d6 (or 10...0-0 11.c5! b6 12.Be2!? bxc5 13.Nxc5 d6 14.Nb3 and White’s bishop pair outweighs the isolated queenside pawns) 11.Bh6 Rg8 12.Qd2² as in Tenev-Chitescu, email 2006; C) 6...d6 7.Nc3 Qb6 is another version of an early ...Qb6, favoured by Savchenko. We have a good counter in 8.Ndb5! Bxc3+ 9.Nxc3 Qxb2 10.Nb5 Kf8 11.Be2!ƒ and with subsequent simple development, White obtained a durable initiative in Sevian-Chizhikov, Stockholm 2017. 7.Nc3 0-0 A) 7...d6 8.Be2 will almost certainly transpose to 7...0-0; B) 7...Ng4 8.Qxg4 Nxd4 (8...Bxd4?! 9.Bxd4 Nxd4 is known to be bad if White plays aggressively: 10.0-0-0 e5 11.f4 d6 12.Qg3 f6 13.f5! Kf7 14.Bd3 Bd7 15.Rhf1ƒ with a strong kingside initiative) is the main alternative, but this has a poor reputation as Black’s concept is quite time-consuming. 9.Qd1 Black has many interpretations of the position, so I’ll cover all the important ones. B1) 9...Nc6 is the alternative retreat to the one to e6, but it’s still quite passive and 10.Qd2 d6 11.Be2 Qa5 12.Rc1 0-0 13.0-0 Be6 14.b3 gives White a nice spatial advantage. As is often the case in the Maroczy Bind, strategic understanding from playing through GM games is more useful than knowing everything move by move, but it should be noted that 14...Rac8 15.f4 f5 16.exf5 Bxf5 17.Bf3 was a fantastic structure for White in Polugaevsky-Suetin, Kislovodsk 1972. White can expand with h2-h3 and g2-g4, or opt for trades of pieces other than rooks in the knowledge that Black’s hanging central pawns will become weaker in the process; B2) 9...e5 10.Bd3 0-0 11.0-0 d6 is a rather passive set-up for Black, but it requires a little finesse to handle the knight on d4: 12.Qd2 Be6 13.Rac1 Rc8 14.b3 a6 15.f3 Qa5 16.Rfd1² White is well placed to deal with ...f7-f5 activity, whereas if Black sits and waits with 16...Rfd8, White can transition to a better endgame with 17.Nd5, or prepare it with 17.Qf2!?N first; B3) 9...Ne6 10.Rc1 and now: B31) 10...Qa5 11.Be2 b6 (11...d6 12.0-0 Bd7 is more passive, and 13.f4!± and f4-f5 will quickly make Black regret his decision) 12.Qd5!? (the most practical, heading for a slightly better endgame, though the main line 12.Qd2 Bb7 13.f3 g5 14.0-0, while less clear to my mind, should also offer an advantage if White plays Rfd1 and a quick a2-a3 and b2-b4) 12...Rb8 (angling for some counterplay if White trades queens; 12...Qxd5 13.cxd5 Nd4 (or 13...Nc5 14.f3²) 14.Bd3± leaves the d4-knight out on a limb, and even in correspondence Black loses a good share of the games) 13.Qxa5 bxa5 14.b3 Bd4 15.Bxd4 Nxd4 16.Nb5! and White won an instructive game in Smeets-Finegold, Al-Ain 2012. The conventional wisdom is that Black should delay castling after ...Qa5, to play on the dark squares with ...g6-g5 and ...h7-h5 at some point: B32) 10...d6 11.Be2 0-0 12.0-0 Bd7?! (12...a5 13.f4ƒ is also unpleasant though) 13.b4 a5 14.a3 axb4 15.axb4 Bc6 16.Qd2 Ra3 17.Nd5±, as in Portisch-Pfleger, Manila 1974, shows a more customary approach to the position; B33) 10...b6 11.Be2 Bb7 12.Qd2 0-0 13.0-0 Nc5 14.f3 a5 15.b3 d6 16.Rb1 Bc6 is a funny transposition to the 7...0-0 line. In this case the normal plan with 17.a3² and preparing the b3-b4 break (such as with Nd5) favours White slightly – a nice example is Schuller-Henderson, corr 2011; B34) 10...0-0 can be met in the standard way, but a more original interpretation is 11.g3!? b6 12.Bg2 Bb7 13.0-0 when the kingside fianchetto nullifies Black’s ...f7-f5 plans: 13...f5 14.Nd5! with the idea 14...Bxb2 15.Rc2 Be5 16.exf5 Rxf5 17.Nxe7+ Qxe7 18.Bxb7±. 8.Be2 d6 8...b6 9.0-0 Bb7 10.f3 has a good reputation for White, as Black’s attempts to break with ...d7-d5 tend to backfire. One tip I can give is that Ndb5 often proves a good move, as ...a7-a6 weakens the b6-pawn. A) 10...d6 only leaves Black with a passive version of the 8...d6 lines: 11.Nc2!? Rc8 12.Qd2² (Karpov-Hamdouchi, Bordeaux rapid 2005) is a neat demonstration of how to improve White’s position from here; B) 10...Rc8 11.Qd2 Qc7 12.Ndb5 Qb8 13.Rac1± illustrates Black’s problems with delaying ...d7-d6, as ...a7-a6 severely weakens the b6-pawn, but Nd5 will soon be quite strong in any case; C) If 10...Nh5, 11.Ndb5!? avoids ...Nf4 tricks, and 11...d6 12.Qd2 a6 13.Na3 Nf6 14.Nc2² saw White coordinate his pieces well for a queenside push in Nester-Savchenko, Pardubice 2006; D) 10...Qb8 11.Qd2 Rd8 is one way to prepare the ...e7-e6/...d7-d5 break. But not for the first time we see that against slow play, we can keep the pieces on the board with 12.Nc2!? d6 13.Rad1 Rd7 14.Bg5!?² with the idea of pushing f3-f4 after tidying up the position with b2-b3 and Kh1; E) 10...e6?! is the most common move, but it doesn’t hold up to scrutiny: 11.Ndb5! d5 12.cxd5 exd5 13.exd5 Nb4 (13...Ne7 14.d6 Nf5 also fails to equalise after 15.Bf2 Ne8 16.d7 Nf6 17.g4! Ne7 18.Bh4 Bc6 (or 18...a6 19.Qd6 axb5 20.Bxf6 Bxf6 21.Qxf6 b4 22.Ne4 Bxe4 23.fxe4±) 19.Qd6 Qxd7 20.Qxd7 Bxd7 21.Rad1± and Black has problems dealing with White’s far more active pieces) 14.d6 Nfd5 15.Bf2 a6 16.Nc7 Nxc7 17.Bxb6 Bxc3 18.Bxc7 Qg5 19.bxc3 Nd5 20.Qd4 Nxc7 21.dxc7± Black will win the c7-pawn, but White is still just a pawn up. 9.0-0 9...Bd7 A) 9...Nxd4 10.Bxd4 is sometimes played to avoid Nc2 lines, but it will just transpose to the main line after 10...Bd7 11.Qd2. Instead, 10...Be6? fails to impress if White follows Fressinet-Kempinski, Germany Bundesliga 2010/11 (10...Bd7 11.Qd3!? is a good independent option, but I’m satisfied with the main line): 11.f4! Rc8 12.b3 Qa5 13.Rc1± and Black will not be able to avert the f4-f5 break forever; B) 9...a6 isn’t a very constructive move, but you sometimes see it from other move orders. In any case, one good counter is 10.Rc1 Bd7 11.f3 Nxd4 12.Bxd4 Rc8 13.Qd2 Be6 14.b3 Nd7 15.Be3² when in Petrosian-Galojan, Yerevan 2014, Black didn’t find a productive continuation. 10.Qd2 10.Nc2!? should also give an edge, but Black can avoid it with 9...Nxd4. 10...Nxd4 11.Bxd4 Bc6 11...a5 12.b3 Bc6 13.f3 is a transposition. 12.f3 a5 12...Nd7 13.Be3 Nc5 14.Rab1 a5 15.b3 is again a transposition. 13.b3 Nd7 14.Be3! It is important to preserve the dark-squared bishops, given White’s pawn chain is on the light squares. 14...Nc5 15.Rab1² We’ve reached the old tabiya position of the whole Maroczy Bind, where Black generally relies on holding the position – the problem is that with careful play, White makes progress on the queenside with a2-a3, b3-b4 and Nd5. That is why the trend has moved toward more aggressive plans with ...e7-e6, ...Be5 and eventually ...f7-f5. 15...Qb6 A) 15...f5?! is the sort of impatient break you’re likely to see at lower levels: 16.exf5 Rxf5 (16...gxf5 17.Nd5± was also much better for White in Tolstikh-Kuzmin, Alushta 2005, as Black’s central structure is very vulnerable to Bg5/Rfe1 attacks) 17.Rbd1 Qb6 18.Nb5ƒ and Black’s position remains passive after further improving moves by White; B) 15...Be5!? tends to transpose into ...e7-e6 territory, such as with 16.Rfd1 e6. An independent try is Oleksienko’s 16.g3!? with the idea 16...e6 17.Nb5, when Black would normally take on b5, but then he’ll lose some time to a later f3f4. But in the event of slower play, 17...Qe7 18.Bg5! Qd7 19.Rfd1 Bxb5 20.cxb5² forces the favourable structure in any case; C) 15...e6!? Even strong GMs have failed to grasp this middlegame, so we should take this variation seriously. Fortunately, by playing Nb5 relatively early we secure a small edge with the bishop pair: 16.Rfd1 (16.Nb5 Bxb5 17.cxb5 Qc7 18.Rfc1 Rfd8 19.Rc2² is a good alternative, playing for a2-a3 and b3-b4. It’s easy to feel that with the doubled pawns, it will be hard for White to win, but the engine confirms that Black has some trouble resolving the pressure down the c-file) 16...Be5 17.g3! (Black was threatening 17...Qh4, so it’s safest to block the bishop’s diagonal) 17...Qe7 18.Nb5! Rfd8 (18...Bxb5 19.cxb5 Rfd8 20.Rbc1 leaves Black too tied up to get in ...f7-f5 in a decent version) 19.Nd4!? (I like this reorganisation, which takes the sting out of ...f7-f5. 19.Bg5 f6 20.Be3 g5 21.Bf1 Kh8 22.Bg2 b6² was played in a couple of correspondence games, but despite the engine’s optimistic evaluation, it’s not that easy to make progress as White) 19...Be8 (19...d5 20.cxd5 exd5 21.Nxc6N 21...bxc6 22.Qc2 provides a pleasant bishop pair edge) 20.Bf1N 20...Bf6 21.Qf2 Bg7 22.Rd2² As usual, Black’s position is solid, but White has a clear plan of Rbd1 and Nb5 to exert long-term pressure. 16.Rfc1 Rfc8 16...Qb4 17.Rc2 leaves Black nothing better than 17...Rfc8 anyway, as 17...f5 18.exf5 Rxf5 19.Qc1! Qb6 20.a3 Qd8 21.b4 axb4 22.axb4 Ne6 23.Qd2² just gives an improved version of the main line with Black having weakened his structure. 17.Rc2! This is a crucial preparation for the a2-a3/b3-b4 plan, as 17.a3? Nxb3! 18.Bxb6 Nxd2 19.Rb2 Nxc4 20.Bxc4 Bd7, winning material, is a nasty trap that has caught out some strong players. 17...Qd8 17...Qb4 18.Qc1 Qb6 19.Bf1 Qd8 20.Qd2 is just a transposition to 17...Qd8 (with two extra moves played). 17...h5 is slightly committal after 18.Nd5! Bxd5 19.exd5² when White will use the weakening ...h7-h5 as a hook for a later g2-g4 and kingside attack. A good example of this point is Bokros-Pinter, Slovakia tt 2001/02. 18.Bf1 The position is not very sensitive to move orders, but we don’t have to rush here, as 18.a3 h5 19.b4 axb4 20.axb4 Na4 21.Nd5 e6 22.Nf4 Nb6! gives Black real counterplay against the c4-pawn. 18...h5 This is usually played with ...Kh7/...Qh8 in mind. It turns out White has quite a few different plans to make progress here, depending on Black’s set-up. The passive 18...b6 19.a3 Ra7 20.Qf2! Be5 21.Rd1 Raa8 22.b4 axb4 23.axb4 Nd7 24.Rcc1² was Percze-Cottegnie, email 2008, a model game White won in a long grind. 18...Be5 19.Rd1 b6 20.g3!? Ra7 21.Bh3² shows an alternative to the queenside plan – White can improve his position with Ne2-d4 and Bh6 and support a steady central advance. 18...Qf8 19.Nd5 Bxd5 20.cxd5!? (20.exd5 and following Holzke-Vuckovic, Germany Bundesliga 2004/05, is the usual continuation) I think this option is a bit underrated. After 20...Nd7 21.Rbc1 Rxc2 22.Qxc2 Nc5 23.g3 Rc8 24.Bh3 Rc7 25.Qe2± Black faces a long and thankless struggle for a draw. 19.a3 Kh7 20.Kh1!? This small improving move emphasises Black’s challenge finding a useful plan. 20...Be5 20...Qh8 is consistent, but Black is very passive in the structure after 21.Nd5 Bxd5 22.exd5!, and faces issues of how to deal with b3-b4/c4-c5 or f4-f5. For example, 22...b6 23.g3 Rcb8 24.b4 Nd7 25.Bh3 Qe8 26.f4 is a rather miserable position for Black – if he plays ...f7-f5, White can reorganise his pieces to target the e7-pawn. 21.b4 Now the game Carlsen-Lie, Gjovik rapid 2009, is a nice model for White to follow, but let’s suppose Black plays the knight to a4. 21...Na4 22.Ne2 axb4 23.axb4 Nb6 Black’s best chance after White plays b3-b4 is probably to pressure the c4-pawn, but it’s insufficient after 24.Rcc1 Be8 25.Nd4± when White is ready to make inroads on the kingside with f4-f5. Summary 4...g6 5.c4: 5...Nf6 6.Nc3 d6: 7.f3 – +0.30 7.Be2 – +0.35 5...Bg7 6.Be3 Nf6 7.Nc3: 7...Ng4 8.Qxg4 – +0.35 7...0-0 8.Be2 b6 9.0-0 Bb7 10.f3 – +0.40 7...0-0 8.Be2 d6 9.0-0 – +0.35 4.1 Yu Yangyi 2750 Vadim Zvjaginsev 2661 China tt 2017 (6) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 g6 5.c4 Nf6 6.Nc3 d6 7.Be2 Nxd4 8.Qxd4 Bg7 9.Be3 0-0 10.Qd2 Be6 11.Rc1 Qa5 12.f3 Rfc8 13.b3 Rab8 14.Na4 Qxd2+ 15.Kxd2² Bd7 15...Nd7!? 16.Nc3 Nc5 can also be met with kingside expansion: 17.g4 a5 18.h4² 16.Nc3 a6 17.g4! Bc6 17...e6 18.a4!? holds back ...b7-b5. 18.b4 18.h4 is met with 18...h5, but 18.Rhd1!? Nd7 19.h4ƒ is one way to prosecute the kingside advance. 18...Be8 19.g5 Nd7 White’s expansion across the board resembles Space Invaders. 20.f4 20.h4! and h5 is more precise. 20...Kf8 20...a5! at least gives Black’s pieces some squares: 21.b5 Nc5 22.Bf3² 21.h4 a5 22.b5 f5?! One can understand Black’s unwillingness to get squashed, but this weakens his structure. 23.gxf6 Nxf6 24.Kd3 24.e5! dxe5 25.fxe5 Nd7 26.e6 Nc5 27.Rcf1+ Kg8 28.Nd5± transforms White’s space into unassailable threats. 24...e6 25.Ba7 Ra8 26.Bd4 One thing I like about the Maroczy is that White doesn’t always have to find the very best moves to keep an edge, this game being a case in point. 26...Bf7 26...Nd7 avoids e4-e5 breaks: 27.Na4 Bxd4 28.Kxd4² 27.e5! dxe5 28.fxe5 The pawn is vulnerable here, so I would prefer 28.Bxe5! Rd8+ 29.Kc2±. 28...Nd7 29.Ne4 Nxe5+ 29...Bxe5 was better. 30.Ke3 Ke7? The decisive mistake, as c5-c6 is a pest. Black had to try 30...Be8. 31.c5 Rd8 32.Rhd1+– Rd5 33.c6 bxc6 34.bxc6 Bh6+ 35.Ng5 Be8 36.c7 Nc6 37.Ba6 37.Bb6! could be played first. 37...Nxd4 38.Rxd4 Rxg5?! Better but also losing is 38...Bd7 39.Rxd5 exd5 40.c8=Q Bxc8 41.Bxc8. 39.hxg5 Bxg5+ 40.Ke4 Bxc1 41.Bb7! 1-0 4.2 Iztok Brunsek 2477 Bostjan Benko 2303 ICCF email 2005 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 g6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.c4 Nf6 6.Nc3 d6 7.Be2 Nxd4 8.Qxd4 Bg7 9.Be3 0-0 10.Qd2 Be6 11.Rc1 Qa5 12.f3 Rfc8 13.b3 a6 14.Na4 Qxd2+ 15.Kxd2 Nd7 16.g4 Rc6 17.h4 Rac8 17...Nc5 18.Nc3 Black is unable to free himself here: 18...b5?! (if 18...Rc7 19.b4 Bxc3+ 20.Rxc3 Nd7 21.Rhc1² and ...a6-a5 can be met with Ra3) 19.Nd5 Bxd5 20.exd5 Rcc8 21.b4 Na4 22.cxb5± 18.h5 Kf8 19.Nc3! b5 Black’s typical break, but it also loosens the queenside. 20.Nd5 bxc4 21.Bxc4 White should retain a set of rooks for his initiative: 21.Rxc4! Rxc4 22.Bxc4 a5 23.Ba6 Rb8 24.Nc7ƒ 21...Ne5 22.Be2 Rxc1 23.Rxc1 Rxc1 24.Kxc1² a5?! 24...gxh5 25.gxh5 a5 avoids the boxing in of the g7-bishop. 25.h6! Bh8 26.Bd2 Nc6 27.Kd1 Be5 28.Nb6 Bd4 28...Nb4 29.Bc4 Bd4 30.Nd5 Nxa2 31.Bxa5 Bc5 32.Kc2 Bxd5 33.exd5 Nb4+ 34.Kc3 Na2+ 35.Kd3 Nb4+ 36.Ke4± gives White scope to make progress on the kingside. 29.Nc4 Bxc4 30.Bxc4 Bb2 30...Bc5 would have been more efficient. 31.Kc2 Ba3 32.f4 e6 33.Kb1 Better was 33.Bc3². 33...Ke7 34.Be3 Bc5 35.Bd2 35.Bxc5 dxc5 36.Kb2 e5!= 35...Ba3 36.g5 Bb4?! 36...Bc5! makes it difficult for White to advance his queenside majority, in light of 37.Kb2 Bd4+ 38.Kc1 Bc5=. 37.Be3 Bc5? 38.Bxc5 dxc5 39.Kb2+– The knight is too slow for this full board ending. 39...e5 39...Nb4?! 40.Bb5! 40.f5 Nd4 41.f6+ Ke8 42.Kc3 Nf3 43.Bb5+ Kd8 44.Kc4 Nxg5 45.Kd5 Ne6 46.Kxe5 Nd4 47.Bd3 g5 48.Bf1 Kd7 49.Bh3+ Kc7 50.Bf5 1-0 4.3 Samuel Sevian 2556 Joel Cholo Banawa 2359 St Louis 2015 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 g6 5.c4 Nf6 6.Nc3 d6 7.Be2 Nxd4 8.Qxd4 Bg7 9.Be3 0-0 10.Qd2 Be6 11.f3 Qa5 12.Rc1 Rfc8 13.b3 a6 14.Na4 Qxd2+ 15.Kxd2 Nd7 16.g4 f5 17.exf5 gxf5 18.h3 Rf8 19.f4 Rad8 20.g5 20...Bf7 A) 20...d5 21.cxd5 Bxd5 22.Rhd1 Bc6 23.Ke1 e5 liquidates the centre, but 24.Nc5 exf4 25.Nxd7 Rfe8 26.Bxf4 Rxd7 27.Rxd7 Bxd7 28.Kd2² retains piece pressure; B) 20...Nc5 21.Nc3! Bd7 (21...Ne4+ 22.Nxe4 fxe4 weakens the structure after 23.Bg4! Bf5 24.Bb6 Rde8 25.Ke3²) 22.Bf3 Bc6 23.Nd5 Rf7 24.Rhe1 (the pressure on Black’s centre forces him to initiate complications) 24...Ne4+ 25.Bxe4 fxe4 26.Bb6 Re8 27.Rxe4! e6 28.Rce1 Rc8! 29.Rxe6 Bxd5 30.Re8+ Rf8 31.Rxf8+ Kxf8 32.f5 Bf7 33.f6 (Black’s g7-bishop ends up lost or trapped) 33...Bxf6 (33...Bh8 34.Re7 Re8 35.Rxb7±) 34.gxf6 Re8 35.Rg1² Better opposite-coloured bishop endgames offer good practical chances with rooks on the board. 21.Bf3 Nc5 22.Nc3 e5 23.Nd5² Kh8 Black doesn’t have an easy way to release the tension, but perhaps he should increase it with 23...b5!? 24.fxe5 Bxe5„. 24.h4! Ne4+? Better was 24...exf4 25.Nxf4 Be5. 25.Bxe4 fxe4 26.f5! This pawn sacrifice completely binds Black’s pieces. 26...Bxd5 27.cxd5 Rxf5 28.Rc7± Kg8 28...b5 29.Rhc1 29.Rxb7 was better. 29...Rf3 30.Rxb7 Rh3 31.Rcc7 Some of the subsequent decisions suggest severe mutual time pressure. 31...Bh8? 31...Bf8 32.Rxh7 Rc8± 32.Rxh7+– Rh2+ 33.Ke1 Rf8 34.g6 34.Rh6! Rf3 35.Rg6+ Kf8 36.Rxd6+– 34...Rc8 35.Bg5 Bf6 36.Kd1? 36.Rb8! Rxb8 37.Bxf6 36...e3? 36...Bxg5 37.hxg5 Rhc2!= 37.Bxe3 e4 38.Rbc7 38.h5! and dancing toward the checking h2-rook was the way to win. 38...Rxc7 39.Rxc7 Rxh4 40.Rf7 Be5 41.a4² White eventually converted his extra pawn, but that is not the subject for an opening manual (1-0, 60). 4.4 Samuel Sevian 2603 Vladislav Chizhikov 2262 Stockholm 2017 (8) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 g6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Bg7 5.c4 Nc6 6.Be3 d6 7.Nc3 Qb6 8.Ndb5 Bxc3+ 9.Nxc3 Qxb2 10.Nb5 Kf8 11.Be2ƒ Nf6 11...Qe5?! 12.0-0! Qxe4 13.c5!± 12.0-0 Kg7 13.Rb1 13.f3! Be6 14.a3 places Black’s queen in some danger of being trapped. 13...Qe5? 13...Qxa2! 14.Ra1 Qb2 is risky, but at least gives Black a second pawn for his suffering. 15.f4!ƒ is an apt reply, with the point 15...Nxe4?! 16.Bf3 f5 17.Nd4 and the dark squares will bleed. 14.f3 h5 15.Qd2± Rb8 16.Nc7 Running Black’s queen out of squares. 16.Nd4!? 16...Ne8 17.f4+– Qf6 17...Qa5 18.Qxa5 Nxa5 19.Bd4+ f6 20.Bxa7 18.Nd5 Qe6 19.f5! Qd7 20.Bxa7 e6 20...Nxa7 21.Qd4+ forks king and knight. 21.Qc3+ Kg8 22.fxg6 fxg6 23.Rf8+! 1-0 4.5 Lev Polugaevsky Alexey Suetin Kislovodsk 1972 (12) 1.c4 g6 2.e4 Bg7 3.d4 c5 4.Nf3 cxd4 5.Nxd4 Nc6 6.Be3 Nf6 7.Nc3 Ng4 8.Qxg4 Nxd4 9.Qd1 Nc6 10.Qd2 Qa5 11.Rc1 d6 12.Be2 0-0 13.0-0 Be6 14.b3 Rac8 15.f4 f5 16.exf5 Bxf5 17.Bf3± Kh8 18.Rfd1 Natural, but the rooks might be best on the bishop’s files! 18.Rf2!? Bd7 19.g3± 18...Rfe8 19.Nb5 Trading queens when holding the better structure has its logic. A trickster would opt for 19.Qf2! Bxc3?! 20.Rd5 Qb4 21.Rb5+–. 19...Qxd2 20.Rxd2 a6 21.Nc3 h5? Black has to break out, or his weaknesses will be hammered: 21...e5! 22.Rxd6 (22.Nd5 exf4 23.Bxf4²) 22...Bf8 23.Rd5 exf4 24.Bxf4 Nb4° provides much-needed activity for a pawn. 22.Na4 22.Ne4 was better. 22...Rb8?! This was the last chance for 22...e5!. 23.c5!± Splitting Black’s hanging central pawns. 23...Nb4 24.Rcd1 Bc2 25.Rc1 Bf5 26.a3?! Now the game loses its theoretical value. 26.h3!, intending g2-g4, was much more useful, as Black wants to play ...Nd3 anyhow. After 26...Nd3 27.Rcd1 Nxc5 28.Nxc5 dxc5 29.Bxc5 b6 30.Bf2 Rec8 Black had equalised, but later he lost anyway. 4.6 Lajos Portisch 2645 Helmut Pfleger 2535 Manila 1974 (11) 1.Nf3 Nf6 2.c4 c5 3.Nc3 Nc6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 g6 6.e4 Bg7 7.Be3 Ng4 8.Qxg4 Nxd4 9.Qd1 Ne6 10.Rc1 d6 11.b4 0-0 12.Be2 a5 13.a3 axb4 14.axb4 Bd7 15.0-0 Bc6 16.Qd2 Ra3 17.Nd5 Black is very passive and most of White’s subsequent decisions will be between several reasonable options. 17...Kh8 Black has trouble changing the position: A) 17...Bxd5?? 18.cxd5 Nc7 19.Bb6+–; B) 17...f5? 18.exf5 gxf5 19.b5 Bxd5 20.Qxd5 Qd7 21.Bf3+–; C) 17...Re8 18.Bg4! h5 19.Bb6 Qd7 20.Bh3 Rea8 21.f3 Ra2 22.Qe1 g5 23.Bf5!+– showed the woes of weakening the kingside in Dammer-Warzecha, email 2012. 18.Bb6 18.Rfe1! first is more flexible. 18...Qd7 18...Qa8 19.Nxe7 Bxe4 20.Qxd6± 19.f4 f5 This move is almost always weakening, but few would be willing to allow kingside expansion to boot, e.g. 19...Rfa8 20.f5 Nf8 21.fxg6 fxg6 22.Rf7±. 20.exf5 gxf5 21.Bf3 Or 21.Rfe1. 21...Rfa8 22.Rce1 Ra1 23.b5 Bxd5 24.Qxd5+– Nd8 25.Rxa1 Rxa1 26.Rxa1 Bxa1 27.c5! The passed c-pawn will quash Black’s resistance. 27...e6 28.c6 bxc6 29.bxc6 exd5 30.cxd7 Bf6 31.Bxd5 Kg7 32.Bc4 Be7 33.Kf2 Nc6 1-0 4.7 Jean Claude Schuller 2376 Gregory Henderson 2024 ICCF email 2011 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 g6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.c4 Nf6 6.Nc3 d6 7.Be2 Bg7 8.Be3 0-0 9.0-0 Bd7 10.Qd2 Nxd4 11.Bxd4 Bc6 12.f3 a5 13.b3 Nd7 14.Be3 Nc5 15.Rab1 b6 16.a3² Ra7 16...Qc7 17.Nd5!? Bxd5 18.exd5² is a typical transformation, when White can play f4-f5 or b3-b4 depending on Black’s set-up (18.Qxd5 Rfd8 19.Qd2 e5! and ...Ne6-d4 is harder to crack). 17.Nd5! 17.Bd1 Qa8 18.Bc2² 17...Ra8 17...e6 meets the tactical blow 18.Nxb6! Rb7 19.b4! axb4 20.axb4 Qxb6 21.Qxd6 Nxe4 22.Qd3 Qc7 23.fxe4 Rd8 24.Qc2±. If 17...Bxd5?! 18.cxd5±. 18.Rfd1 Re8 19.Bg5 Be5 19...Ne6 20.Bh6 Bxh6 21.Qxh6ƒ hands White good attacking chances with h4-h5, but in the game Black’s knight sinks in quicksand. 20.b4 axb4 21.axb4 Na4?! 22.Rbc1± Qd7 23.Rc2 Bxd5 24.Qxd5 Qa7 25.Qd2 Rec8 26.Be3 Qb8 27.f4 Bg7 28.Bf3 Ra7 29.Bg4 Re8 30.Bd4 Now White plays on the kingside, as far away from the a4-knight as possible. 30.Rdc1± 30...Bh6? 30...Bxd4+ 31.Qxd4 Rc7 32.f5!± 31.e5!+– Rd8 31...dxe5 32.Bxe5 Qxe5 33.fxe5 Bxd2 34.Rdxd2 32.e6 White’s space advantage on the kingside translates to a decisive attack. 32...f5 33.Bxf5! Rf8 33...gxf5 34.Qf2 Qc8 35.Qg3+ Kf8 36.Re1 34.Be4 d5 35.cxd5 Bxf4 36.Qd3 Bxh2+ 37.Kh1 Rf4 38.Bxg6 Rh4 39.Bxh7+ 1-0 4.8 Jan Smeets 2614 Benjamin Finegold 2498 Al-Ain 2012 (1) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 g6 5.c4 Bg7 6.Be3 Nf6 7.Nc3 Ng4 8.Qxg4 Nxd4 9.Qd1 Ne6 10.Rc1 Qa5 11.Be2 b6 12.Qd5 Rb8 13.Qxa5 bxa5 14.b3 Bd4 15.Bxd4 Nxd4 16.Nb5!² Nc6?! After 16...Nxe2 17.Kxe2 a6 18.Nc3 Bb7 19.Rhd1 Black would be robustly placed, but for the fact he can’t hold back both c4-c5 and e4-e5: 19...Bc6 (19...f6 20.c5!²) 20.e5!N 20...Bxg2 21.f3ƒ 17.f3 17.0-0 17...a6 18.Nc3 e6 18...Nd4!? 19.Kf2 Ke7 20.Rhd1± g5 20...d6 21.Rd2 21.c5! 21...h5 22.h4! f6 23.c5 Black’s structure is growing weaker by the move. 23...Rb4 23...Bb7 24.Na4 Ne5 25.Nb6± 24.Rcd1 Ne5 25.Na4 Bb7 26.Nb6 Bc6 27.Bxa6 27.hxg5 fxg5 28.Bxa6 27...Rg8 Possibly time pressure was the cause of the forthcoming indecisive play of our combatants. 28.Be2 28.Rb1! a4 29.Rdd1 28...gxh4! 29.Rd4?! 29.Rd6± 29...Rxd4 30.Rxd4 Ng6? 30...h3! 31.gxh3 h4 with ideas of ...Rg3/...Ne5-g6-f4 shifts the game’s trend. 31.a3 Nf4 32.Bf1± e5? 32...Rb8 33.b4 axb4 34.axb4 33.Rd6 33.Rd1 was better. 33...Rb8 34.Rd1 Ne6 35.b4 axb4 36.axb4 Nd4 37.Bc4 37.Ba6! prevents 37...d6? due to 38.b5!. 37...d6! 38.Rh1 dxc5? 38...f5! was the only way to disrupt White’s hold. Now Black gets ground down. 39.bxc5 Ne6 40.Bxe6 Kxe6 41.Rxh4 Rd8 42.Rxh5 Rd2+ 43.Kg3+– Rc2 44.Rh7 Rxc5 45.Nc8! Bxe4 46.Re7+ Kd5 47.fxe4+ Kxe4 48.Nd6+ Kd5 49.Nf5 Ke4 50.Kg4 Rc2 51.g3 Rc6 52.Rd7 Ra6 53.Rd6 Rxd6 54.Nxd6+ Kd5 55.Ne8 Ke6 56.Ng7+ Kd5 57.Kf5 e4 58.Ne6 e3 59.Nf4+ 1-0 4.9 Anatoly Karpov 2674 Hicham Hamdouchi 2559 Bordeaux 2005 (3) 1.Nf3 Nf6 2.c4 c5 3.Nc3 g6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 Bg7 6.e4 d6 7.Be2 Nc6 8.Nc2 0-0 9.0-0 b6 10.Be3 Bb7 11.Qd2 Rc8 12.f3² Ne5 Black has several options, but White can meet them in a similar way: A) 12...Qd7 13.Rfd1 Rfd8 14.Rac1 Qe8 15.Na3!? Qf8 16.Nab5ƒ; B) 12...Qc7 13.Rac1 Qb8 14.b3 Rfd8 15.Rfd1 Ne5 16.Nd5 Re8 17.Bg5 forced Black back in Radovanovic-Herman, Novi Sad 2016; C) 12...Nd7 13.Rad1 f5?! 14.exf5 gxf5 15.f4!±; D) 12...Re8 13.Rad1 Ne5 14.b3 Qc7 15.Nb4!? Qb8 16.Nbd5 Nxd5 17.exd5 Nd7 18.f4ƒ 13.b3 a6 14.Rac1 Ned7 15.Nb4 Or 15.Rfd1 Re8 16.Nb4. 15...Re8 16.Rfd1 Nc5 17.Bf1 Karpov makes incremental improvements to run Black’s clock down, but 17.Nbd5! was more incisive. 17...Nfd7 18.Kh1 Be5 18...Ne5 19.Nbd5 e6?! Black tires of shuffling, but the pawns can’t move back! 19...Bc6 20.Ne2 a5 21.Nd4 Bb7 22.Nb5± 20.Nf4± Bc6 21.Nh3 21.Nfe2! 21...Qc7 22.Nf2 Qb7?! 22...f5 prevents Ng4, albeit by further compromising his structure. 23.Ng4+–... 1-0 (31) 4.10 Laurent Fressinet 2718 Robert Kempinski 2615 Germany Bundesliga 2010/11 (1) 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 Bg7 4.e4 0-0 5.Be2 d6 6.Nf3 c5 7.0-0 cxd4 8.Nxd4 Nc6 9.Be3 Nxd4 10.Bxd4 Be6 11.f4 Rc8 12.b3 Qa5 13.Rc1± a6 13...b5 fails to 14.f5!. 14.a4 Kh8 14...b5 15.axb5 axb5 16.f5!; 14...Rfe8 15.Kh1 Qc7 16.f5 Bd7 17.Qd3 b6 18.Rcd1± 15.Kh1 15.Qd3!? 15...Ng8?! This looks bad, but who wants to play the computer’s move 15...Kg8 ? 16.f5! Bd7 17.Nd5 Bxd4 17...Qd8 18.Qxd4+ f6 The rest is a matter of technique – just look at Black’s pieces! 19.b4!? 19.fxg6 hxg6 20.Rc3+– 19...Qd8 20.Nb6 Rc7 21.Rcd1 21.Qe3!? 21...Qe8 21...gxf5 22.exf5 Nh6 23.c5! Nxf5 24.Qf2± 22.a5 Bc6 23.Qe3 23.Rd3! is not the first chance White has had for an attacking rook lift, but he opts to win on the queenside. 23...Kg7 24.Rc1 Nh6 25.b5 Bd7 26.bxa6 bxa6 27.c5 Bb5? 27...Rxc5 28.Rxc5 dxc5 29.Qxc5 Bc6± keeps hope alive. 28.Nd5+–... 1-0 (31) 4.11 Tigran S Petrosian,T. 2425 Lilit Galojan 2317 Yerevan EU-ch 2014 (6) 1.Nf3 Nf6 2.c4 c5 3.Nc3 g6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 Bg7 6.e4 d6 7.Be2 0-0 8.Be3 Nc6 9.0-0 Bd7 10.Rc1 a6 11.f3 Rc8 12.Qd2 Nxd4 13.Bxd4 Be6 14.b3 Nd7 15.Be3 15...Nc5?! This amounts to shuffling. A) 15...Qa5?! 16.Nd5!; B) 15...f5?! 16.exf5 Rxf5 (16...gxf5 17.f4!) 17.f4±; C) 15...Kh8 16.Nd5 Kg8 17.b4 is a comical transposition to the game; D) 15...Re8 16.Nd5 a5 (16...Bxd5 17.cxd5 Nf6 (17...Nc5 18.Rc2±) 18.Qb4 Qd7 19.Rc4±) 17.f4 f5 18.exf5 Bxf5 19.Bf3± We’ve seen this type of dream position before. 16.b4! Nd7 17.Nd5± b6 17...Nf6 18.Bb6 Qe8 makes the best of an adverse situation. 18.Rfd1 18.Nf4!? 18...a5 19.a3 Rb8 20.Nf4 axb4 21.axb4 Black can’t avoid further structural degradation. 21...Kh8 21...Bh6 22.h4! 22.Nxe6 fxe6 23.f4 e5 24.f5! Qe8 24...gxf5 25.exf5 Rxf5 26.c5! bxc5 27.bxc5+– 25.Rf1 Nf6 26.Bf3 b5 27.c5 1-0 The game score must be incomplete, though White is strategically winning by now. 4.12 Nikolay Tolstikh 2375 Gennady Kuzmin 2510 Alushta 2005 (7) 1.Nf3 c5 2.c4 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 g6 5.e4 Bg7 6.Be3 Nf6 7.Nc3 0-0 8.Be2 d6 9.0-0 Bd7 10.Qd2 Nxd4 11.Bxd4 Bc6 12.f3 a5 13.b3 Nd7 14.Be3 Nc5 15.Rab1 f5 16.exf5 gxf5 17.Nd5± 17...Rf7 As Black’s pawns advance, they become more vulnerable to attack: 17...e6 18.Bg5! Qb8 19.Nf4 Qc7 20.Rbd1±; or 17...Bxd5 18.cxd5 Qe8 19.Rbc1 b6 20.Rfe1±. 18.Rbd1 The classic ‘wrong rook’ question, though it doesn’t matter too much. Slightly better was 18.Rfd1! Kh8 19.a3. 18...e6 19.Nf4 Rd7 20.Nh5 Qf8?! 20...Be5 21.Qe1!ƒ 21.Qe1 A nice manoeuvre to target Black’s open king. 21...Qf7 22.Qh4 e5 23.f4 23.Rd2!? 23...Ne6? 23...Ne4 24.fxe5 dxe5 25.Rxd7 Bxd7 26.Bd3+– f4 27.Bxh7+! Most winning middlegames are converted by tactical means. 27...Kxh7 28.Nxf4+ Kg8 29.Nd5 1-0 4.13 Albert Bokros 2420 Erik Pinter 2416 Slovakia tt 2001/02 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.f3 Nc6 6.c4 g6 7.Nc3 Bg7 8.Be3 0-0 9.Be2 Bd7 10.0-0 Nxd4 11.Bxd4 Bc6 12.Qd2 a5 13.b3 Nd7 14.Be3 Nc5 15.Rab1 Qb6 16.Rfc1 Rfc8 17.Rc2 h5 18.Nd5 Bxd5 19.exd5 Qd8 20.f4 20.a3 and b2-b4 is the other plan, but it’s arduous for Black to swing pieces to the defence of the kingside. 20...Kh7? Black can’t be successful with a passive defence, and should change the position: 20...Qd7 21.Bf3 e5! 22.dxe6 Qxe6 23.Bxc5 dxc5 24.Bxb7 Rd8 25.Qe2 Ra7 26.Qxe6 fxe6 27.Be4 Bd4+ 28.Kh1 Kg7 and Black has a fortress in this pawndown ending. 21.Rf1 21.f5!± could have been played without preparation. 21...f5 22.Bf3± Qh8 23.g3 Rcb8 24.h3! b5 24...Qc8 was preferable. 25.g4 bxc4 26.Rxc4 Rb4 27.gxf5 gxf5 28.Qc2! Rf8 29.Kh2 29.Kh1! avoids a check in the next note. 29...h4? 29...Rxc4 30.Qxc4 Bh6 31.Bxh5 Ne4 32.Bf3 Qb2+ 33.Qe2 Qxe2+ 34.Bxe2² 30.Rg1+– Black’s pieces are too awkward to cover the g-file. White won on move 49. 4.14 Frank Holzke 2492 Aleksandar Vuckovic 2325 Germany Bundesliga 2004/05 (6) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 g6 5.c4 Bg7 6.Be3 Nf6 7.Nc3 0-0 8.Be2 d6 9.0-0 Nxd4 10.Bxd4 Bd7 11.Qd2 Bc6 12.f3 a5 13.b3 Nd7 14.Be3 Nc5 15.Rab1 Qb6 16.Rfc1 Rfc8 17.Rc2 Qd8 18.Bf1 Qf8 19.Nd5 Bxd5 20.exd5ƒ As we have seen this structure before, most of the ideas are apparent. 20...h5 20...Qd8 21.a3 b6 22.g3ƒ; 20...Rc7 21.Re1 b6 22.Rcc1±; 20...Be5 21.g3 f5?! 22.Bh3 Bg7 23.Re1± 21.Re1 21.g3 Rc7 22.Bh3± 21...Kh7 The f4-f5 plan of the previous game is less effective, but g2-g4 is a good substitute. 22.h3!? 22.g3 22...Rc7 22...Kg8 23.g4 hxg4 24.hxg4± 23.g4± Bh6 24.f4! hxg4 25.hxg4+– Kg8 26.Bh3 26.Qh2! 26...Bg7 27.f5! The opening of the kingside settles the issue. 27...Be5 28.fxg6 fxg6 29.Bxc5 Rxc5 30.Rf1 Qg7 31.g5 Bd4+ 32.Kh1 Qh7 33.Kg2 Qh4 34.Be6+ Kg7 35.Qf4 1-0 4.15 Magnus Carlsen 2776 Kjetil Lie 2539 Gjovik rapid 2009 (1) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 g6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Bg7 5.c4 Nc6 6.Be3 Nf6 7.Nc3 d6 8.Be2 0-0 9.0-0 Nxd4 10.Bxd4 Bd7 11.Qd2 Bc6 12.f3 Nd7 13.Be3 a5 14.b3 Nc5 15.Rab1 Qb6 16.Rfc1 Rfc8 17.Rc2 Qd8 18.Bf1 h5 19.a3 Kh7 20.Kh1 Be5 21.b4 axb4 21...Na4 22.Ne2 Qh8 23.Nd4 Bd7 24.f4 Bf6 25.Be2± 22.axb4 Ne6?! 23.Nd5± As we know already, Black struggles to counter full-board play with f4-f5. 23...Ra3 24.f4 Bg7 25.f5 25.Re1!? was more restrained, but Carlsen’s play quickly gives him a winning position. 25...Nf8 26.Bg5 Bxd5 26...Bf6 was ugly but necessary. 27.Qxd5 e6 28.fxe6 fxe6 29.Qxb7 Qxg5 30.Qxc8+– One does not need to be a super-GM to convert White’s material advantage. Carlsen won on move 48. Chapter 5 The Sveshnikov 5...e5 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 Let’s start from move 1. 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Here 5...e6 transposes to the Four Knights and 5...d6 to the Classical. 5...e5 The Sveshnikov gives Black more active piece play than most other Open Sicilians, but like the Kalashnikov it entails some positional concessions. 6.Ndb5 d6 6...h6?! 7.Nd6+ Bxd6 8.Qxd6 Qe7 9.Qxe7+ Kxe7 This is an endgame where Black scores respectably, but pressuring the d6 weakness with 10.b3! d6 11.Ba3 poses some tricky questions, e.g. 11...a6 (if 11...Be6 12.0-0-0 Rhd8 13.Nd5+ Bxd5 14.exd5 Nb8 15.Re1! Nbd7 16.f4 e4 17.Bd3 pins and wins material) 12.0-0-0 Rd8 13.Bc4 Be6 (or 13...b5 14.Bd5 Bd7 15.f4!ƒ and the king feels uncomfortable on e7) 14.Nd5+ Bxd5 15.exd5 (A.Horvath-P.Kiss, Hungary tt 2010/11) 15...b5 16.Bd3!? b4 17.Bb2 Nb8 18.f4! and White again uses his bishop pair dynamically to secure a considerable advantage. 7.Bg5 a6 Otherwise Nd5 will hurt. 8.Na3 b5 This move defines the Sveshnikov, though in my experience White has a few options where it’s quite hard for Black to play for a win. Bird Variation Perhaps this is the reason some strong players have employed the Bird Variation 8...Be6, although I don’t feel Black can equalise after 9.Nc4 followed by playing to dominate the d5-square. A) 9...Rc8 is the old main line, but White can either grab a lazy edge with 10.Bxf6 or punish Black with 10.Nd5 Bxd5 11.Bxf6 gxf6 12.Qxd5, when Black has the bad structure without the dynamism: 12...Nd4 (the one forcing line White really should remember when entering this variation is 12...Nb4 13.Qd2 d5 14.exd5 Nxc2+ 15.Qxc2 Bb4+ 16.Kd1 Qxd5+ 17.Kc1 0-0 18.Kb1 Rfd8 19.a4!± and White will secure the extra knight with a4-a5. If 19...b5?! 20.axb5 axb5 21.Ne3 retains the extra piece) 13.Bd3! (13.0-0-0 b5 14.c3 Bh6+ 15.Ne3 Rc5 16.Qb7 Rc7! 17.Qxa6 Qb8, trapping White’s queen with ...Ra7, is an important trap to avoid) 13...b5 14.Ne3 Bh6 15.c3 Now the ...Rc5 tricks don’t work, and 15...Bxe3 16.fxe3 Ne6 17.0-0 was depressing for Black in Baranowski-Zlotkowski, email 2010; B) 9...Rb8!? Black is placing the rook out of the way of Bxf6 Qxf6 Nb6, but it’s a bit passive. 10.Nd5! (once again, the best move) 10...Bxd5 11.exd5 Ne7 12.Bxf6 gxf6 13.a4 Black will fall into a positional bind on the queenside with a4a5, and compared to a normal Sveshnikov, his kingside play is too slow: 13...f5 (13...Bg7 14.Qg4!? Kf8 15.Bd3 Nxd5 16.0-0ƒ is a strong pawn sacrifice, keeping the g7-bishop out of play) 14.a5 Bg7 15.g4! fxg4 (other moves are treated in Kryvoruchko-Iturrizaga Bonelli, Spain tt 2016) 16.Qxg4 0-0 17.Rg1 Ng6 18.Bd3 Rc8 (18...e4 does not solve the problems: 19.Bxe4 Rc8 20.Bd3 Rc5 21.Qh5 Qe8+ 22.Kf1 Qb5 23.Nxd6) 19.Ne3 e4 20.Qxe4 Bxb2 21.Rb1 Qxa5+ 22.Kf1² As before, White’s kingside initiative with the opposite-coloured bishops outweighs Black’s extra pawn. 9.Nd5! After my futile efforts to make 9.Bxf6 work, I saw the positional approach is both safer and stronger. 9...Be7 A) 9...Be6? 10.Bxf6 gxf6 11.c3± and Nc2-e3 doesn’t require a special analysis; B) 9...Qa5+ 10.Bd2 Qd8 is a tacit draw offer as 11.Bg5 repeats, but we should seize the advantage with 11.Bd3!? (11.c4 should also favour White, but is more complicated) 11...Nxd5 (11...Rb8 12.0-0 Be7 13.Nxe7 Nxe7 14.c4 also favours White, with the bishop pair and a nice structure) 12.exd5 Ne7 13.c4² White has some initiative, see Zakharov-Masarik, email 2010. 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 10...gxf6? 11.Bd3 is already positionally lost for Black. 11.c3! White’s basic plan is Nc2 and a2-a4, to weaken Black’s queenside and maintain the d5 outpost with Nce3 or Ncb4. 11.c4 b4 12.Nc2 is the main trend, but I see absolutely no advantage for White after 12...0-0 13.g3 a5 14.Bg2 (or 14.h4 Be6 15.Bh3 a4!=) 14...Bg5 15.0-0 Ne7=. 11...Bg5 It is not so easy for Black to do without this move. Alternatives to 11...Bg5 A) 11...Be6?! only misplaces the bishop after 12.Nc2 0-0 13.a4 Ne7 14.Nxf6+ gxf6 15.Bd3² with an improved version of the 9.Bxf6 lines in Baghdasaryan-Shomoev, Kazan 2016; B) 11...Rb8 12.Nc2 will almost certainly transpose to 11...Bg5 or 11...0-0; C) 11...Bb7?! is also not the ideal placement for the bishop: 12.Nc2 Nb8 (12...Ne7 13.Nxf6+ gxf6 transposes to 11...Ne7) 13.a4 (13.c4!? is also promising, but one good line is sufficient) 13...bxa4 14.Rxa4 Nd7 15.Bc4 0-0 16.Qe2 a5 17.0-0 Bg5 18.Rfa1² White has a fine version of a normal position because of Black’s slow Breyer-style manoeuvre. See Kudrin-Ochoa de Echaguen, New York 1992; D) 11...Ne7 12.Nxf6+ gxf6 insists on the doubled f-pawns structure, but here Black doesn’t have the bishop pair as compensation: 13.Nc2 (13.g3!? Bb7 14.Bg2 f5 15.Qe2² is also a bit better for White, but Black could dodge this option with the 11...Bb7 move order) 13...Bb7 14.Bd3 (Black must create counterplay fast or his structure will simply be inferior) 14...d5 (14...f5? gives up the initiative after 15.exf5 Bxg2 16.Rg1 Bb7 17.a4± Szczepankiewicz-Krebs, email 2000) D1) 15.exd5 Qxd5 16.Ne3 Qe6 17.Qc2 e4 18.Be2 f5 19.g3 scores well, but Black has a defence: 19...0-0 (19...Ng6 20.0-0-0 0-0 21.Kb1 f4 22.gxf4 Nxf4 23.Rhg1+ Kh8 24.Bg4² was Kravtsiv-Zinchenko, Simferopol 2004) 20.0-0-0 Qxa2! 21.Rd7 Nc6 22.Qb1 (Popov-Thierry, email 2005) 22...Qxb1+ 23.Kxb1 Bc8 24.Rc7 Nd8 25.f4 Ne6 26.Rc6 Rd8 and the endgame proves fine for Black; D2) 15.Qe2!? is a safe route to a small edge, keeping the tension, e.g. D21) 15...f5?! 16.exf5 e4 17.f6! Ng6 18.Qe3 Qxf6 19.g3 clearly favoured White in Minasian-Esen, Moscow 2006, as he dominates the dark squares; D22) 15...Qb6 16.0-0-0 0-0-0 17.exd5 Nxd5 (17...Kb8 18.Rhe1 Bxd5 19.a3! is strong, as we don’t have to fear 19...Bxg2 20.f4 Qb7 21.Rd2 Bf3 22.Qe3 Ng6 23.Bxg6 hxg6 24.fxe5 with a stable edge because of the better minor piece and Black’s weaker king) 18.g3 If Black does nothing, White improves his position with Be4/Rhe1/Kb1 in some order and sits on his superior structure. But the direct 18...b4 19.cxb4 Nxb4 also doesn’t help after 20.Qg4+ Kb8 21.Qxb4 Qxb4 22.Nxb4 a5 23.Na6+ Ka7 24.Rhe1 Bxa6 25.Bxa6 Kxa6 26.Re4! and despite the equal material, Black’s weak structure gives White serious winning chances; D23) 15...dxe4 16.Bxe4 Bxe4 17.Qxe4 Qd5 18.Qxd5 Nxd5 19.0-0-0 0-0-0 20.g3 This is an unpleasant endgame for Black due to his inferior pawn structure, e.g. 20...Rd7 21.Rhe1 h5 (21...Rhd8 22.Rd3 Ne7 23.Rxd7 (Alsina LealMartorell Aubanell, Sabadell 2008) 23...Kxd7 24.a4!² and Re4 creates further weaknesses in Black’s structure) 22.a4! h4 23.axb5 axb5 24.Re2 Kc7 25.Red2 hxg3 26.hxg3 Rhd8 27.g4² With precise defence the engine neutralises White’s edge, but he still has some problems to solve as his pawns are all fixed; E) 11...0-0 12.Nc2 Rb8 is unfashionable because of 13.h4! and Black has difficulty activating his dark-squared bishop: E1) 13...g6 has been successful in correspondence, but feels like a positional mistake due to giving a hook for h4-h5: 14.g3 Bg7 (14...h5 15.a4 bxa4 16.Nce3! is very powerful: 16...Rxb2 17.Qxa4 Bd7 18.Qa3±) 15.h5 Ne7 16.Nce3 Nxd5 17.Nxd5 Be6 (17...Bb7 18.Be2 Bf6! 19.Qd3 Bg5 led to a draw in Bauer-Meissen, corr 2013, but a slight improvement is 20.a3!? with the positional idea of Bd1-b3, holding back ...f7-f5, as demonstrated by 20...Qe8 21.Bd1 Kg7 22.Bb3 Qd7 23.Rd1 and Black is solid but passive) 18.Bh3!? Qd7 19.Bxe6 fxe6 20.hxg6! hxg6 21.Ne3 White has a stable advantage based on his superior structure, e.g. 21...Qf7 (21...Qc6 22.Qd3 Rbd8 23.Rd1 Rd7² is probably best, but Black remains tied down) 22.0-0 Rbd8 23.a4 d5 24.Qe2 dxe4 25.axb5 axb5 26.Ra6! and Black’s attempt to break out has only increased his positional woes; E2) 13...Be6 14.a3!N 14...Bxd5 15.Qxd5 is a durable edge for White because of the superior bishop, which isn’t changed by 15...Ne7 16.Qd3 d5 17.exd5 Qxd5 18.Qxd5 Nxd5 19.0-0-0 Rfd8 20.g3²; E3) For 13...a5 see Schuller-Dunlop, email 2014; E4) 13...Be7 14.Nce3 (14.g3 Be6 15.a3 is another possibility, see Karjakin-Shirov, Heraklion 2007) 14...Be6 15.a4 Qd7 16.axb5 axb5 (in the other lines Black can avoid this b5-weakness with ...bxa4) 17.Be2 Bd8 18.h5 This position has been tested extensively in correspondence chess, where Black mostly holds the draw, but the d6-weakness condemns him to a long defence, which is hardly pleasant in an over-the-board game: E31) 18...h6 19.0-0 Bg5 20.Ra6² will be considered in Percze-Raivio, email 2011; E32) 18...Bg5 19.0-0 Rfd8 (19...b4?! 20.Ra6! bxc3 21.bxc3± gives mostly wins in correspondence) 20.b4! Bxe3 21.Nxe3 Ne7 22.Qd3 d5 23.exd5 Nxd5 24.Nxd5 Bxd5² gives White a few promising tries, as we’ll see in OliveiraMyakutin, email 2011; E33) 18...b4 19.Ra6 bxc3 20.bxc3 Kh8 This has led to all draws in correspondence, but I have a novelty: 21.Nc4!?N, reshuffling the knights to target d6: 21...f5 (Black resorts to forcing play to resolve his problems; 21...Rb7 22.Nde3 Be7 23.0-0 Nb8 24.Ra8 Nc6 25.Ra1² is a persistent white edge, due to the pressure on d6) 22.exf5 Bxd5 23.Qxd5 Rb1+ 24.Bd1 Qxf5 25.0-0 Nd4 26.Ra2 Nb5 27.Nxd6 Nxc3 28.Qc4 Qf6 29.Ne4 Qf4! 30.Qxc3 Qxe4 31.Qc5 (if Black could get in ...Bb6 the position would be easy to hold, but White can keep Black tied up) 31...Qf4 (or 31...Re8 32.Ra6!) 32.Ra8 and White retains winning chances because of his more active pieces. 11.c3 Bg5 main line 12.Nc2 This position represents the main crossroads, with no less than three plans for Black. 12...Rb8!? This anticipates our a2-a4 plan, though we can play it regardless. A) 12...Ne7!?, challenging our control of d5, is the toughest line to crack, though Black is playing purely for a draw: A1) 13.a4 bxa4 14.Bc4!? is a decent surprise if you think your opponent knows the drawing line after 13.h4, though Black’s position is pretty decent after 14...Rb8! (14...Bd7?! 15.h4! Bh6 16.g4ƒ is unpleasant for Black; 14...0-0 15.Rxa4 a5 16.0-0 meanwhile move orders Black into the 12...0-0 variation) 15.Ncb4 Bd7 16.Bxa6 Qa5N (16...Nxd5 17.Qxd5 0-0 18.0-0 Qb6 19.Qd1! with the idea of Bd3-c2 gives White something to work with) 17.Qe2 Nxd5 18.Nxd5 Qc5 19.0-0 0-0 20.Bc4 g6 21.Nb4 Rbc8 22.Bd3 Kg7= and Black can sit on this position unperturbed; A2) 13.h4 Bh6 14.a4 (14.Ncb4 0-0 15.a4 gives the extra option of 15...Nxd5!? 16.Nxd5 Be6, which was fine for Black in Matyukhin-Grigoryev, email 2007, despite White’s eventual win) 14...bxa4 15.Ncb4 0-0 (15...Bd7 16.Rxa4! is a standard positional exchange sacrifice, as we’ll observe in Karjakin-Radjabov, Warsaw 2005): A21) 16.Qxa4 a5 17.Bb5 Nxd5 18.Nxd5 Be6 (18...Kh8?! 19.b4 f5 20.Bc6 Ra7 21.b5! fxe4 22.Qxe4 gave White positional domination in Müller Alves-Taboada, email 2008. In the 12...Rb8 line we’ll see White sacrifice an exchange to reach such a set-up) 19.Bc6 Rb8 20.b4 axb4 21.cxb4 (White would be much better if he could consolidate, but Black can create counterplay) 21...Kh8 (21...Bxd5?! 22.Bxd5 Qb6 23.Rb1! Kh8 24.0-0² is a tough position to hold because of Black’s offside bishop, see Leko-Carlsen, Linares 2008) 22.b5 Bxd5 23.Bxd5 Qb6 24.0-0 (24.Bc6 Be3!= is a crucial trick) 24...Qxb5 25.Qxb5 Rxb5 26.Ra6 The endgame is a draw, but Black must be accurate: 26...f5!? (the exchange of pawns helps the inferior side to defend; 26...f6 27.Rxd6 Bd2² is the engine’s way of defending, but it looks a bit awkward from a human perspective) 27.Rxd6 fxe4 28.Bxe4 Rb4 29.Re1 g6 30.h5 Rb2 31.f3 Rd2 32.Rxd2 Bxd2 33.Re2 Rd8 34.hxg6 hxg6 35.Bxg6 Kg7 36.Be4 Kf6 and White’s extra pawn can’t be exploited; A22) 16.Rxa4!? would be my recommendation if White wants to avoid the drawish line, since he can count on the faintest of edges here: 16...a5 (16...Nxd5 17.Nxd5 a5 18.g3 Kh8 19.Bg2 Rb8 20.b3² keeps Black in a bind) 17.Nxe7+ Qxe7 18.Nd5 Qb7! 19.b3 Kh8 20.Bc4 f5 (Black should start with this move, so he can play ...Bd7 with tempo later) 21.exf5 Bxf5 22.0-0 (White doesn’t have to be nervous about the combination of 0-0/h2-h4, as Black is too tied down to exploit it) 22...Bd7 23.Ra2 Bc6 24.Qd3 a4 (the computer idea 24...Qd7!? doesn’t fully equalise after 25.Nb6 Qg4 26.Bd5) 25.bxa4 Rxa4 26.Rxa4 Bxa4 27.Rb1 Qf7 28.Rb2 and White has some slight chances because of the misplaced h6-bishop. B) 12...0-0 13.a4 bxa4 14.Rxa4 a5 (14...Rb8?! 15.h4! Bh6 16.Bxa6 is a safe pawn grab, as 16...Rxb2 17.Bxc8 Qxc8 18.Rc4!±, threatening 19.Rxc6, is very unpleasant) is the old main line and was Kotronias’s recommendation in GM Repertoire: Sveshnikov Sicilian, but it has come under pressure of late: 15.Bc4 Rb8 (Radjabov’s 15...Bd7! might be Black’s best line, to rapidly trade White’s d5-knight. In Anand-Radjabov, Monaco 2007, I show the precision White must display to claim any edge) 16.b3 Kh8 17.Nce3! and now: B1) 17...Be6 18.h4!? Bxe3 19.Nxe3² is a nice material distribution for White, as demonstrated in CraciunescuBennborn, email 2008; B2) 17...Bxe3 18.Nxe3 Ne7 19.0-0 f5 20.exf5 Bxf5 (20...Nxf5?! 21.Nxf5 Bxf5 22.Qd5 wins a pawn for no compensation, as demonstrated in several games) 21.Ra2!² White won a nice game by switching between Black’s weaknesses in Leko-Radjabov, Morelia 2008; B3) 17...g6?! was the main line, but it is under a cloud because of the gambit 18.h4! Bxh4 19.g3 Bg5 (after the logical defence 19...Bf6 20.Ra2 Bg7 21.f4! is very strong) 20.f4 exf4 21.gxf4 Bh4+ 22.Kf1 f5 23.Ra2 fxe4 24.Rah2 g5 25.Qh5. White has a winning attack with best play, as we’ll witness in Giri-Shirov, Hoogeveen 2014; B4) 17...Ne7 was Kotronias’s recommendation, so I’ve made it my main line: 18.Nxe7 Qxe7 19.Nd5 Qd8 20.0-0 f5 21.exf5 Bxf5 22.Ra2! Rc8 (22...Bd7 23.Bd3!? and Be4 shows the issue with vacating this diagonal) 23.Qe2 Be6 24.Rd1 As I previously noted in the 50 Moves Magazine, the position is a mutual zugzwang according to the computer – although I would be hard pressed to explain why! 24...Rc5 (24...Bh4 25.g3 Bg5 is another attempt to wait, but then we might slowly improve the position with e.g. 26.Ra4!? Bd7 27.Bb5² followed soon by c3-c4) 25.g3!? looks slightly better for White, in case one wishes to avoid a drawish endgame (25.b4 axb4 26.cxb4 Rc6 27.b5 Rc5 28.Rb2 – I stopped here in my previous analysis, but let’s continue: 28...Qa5! 29.g3 Qa4 30.Nb6 Bxc4 31.Nxa4 Bxe2 32.Rxe2 Rxb5 33.Rxd6 Kg8² The endgame is a draw, but White can press a bit, Laane-Kurgansky, email 2008) 25...Qb8 26.h4 Bh6 (Evans-Massimini Gerbino, email 2008) 27.b4 axb4 28.cxb4 Rcc8 29.Nb6!? (29.b5 is the other approach) 29...Qxb6 30.Bxe6 Rc3 31.Kg2 Qxb4 32.Bd5 and though White is down a pawn, his far superior bishop gives him real winning chances. This theme constantly crops up in this variation. 13.a4 13.h4!? Bxh4 14.g3 Bg5 15.f4 exf4 16.gxf4 Bh4+ 17.Kd2 is an interesting pawn sacrifice, but not enough for an edge after 17...Ne7!N. 13...bxa4 14.Ncb4 Nxb4 15.cxb4 Bd7 Prompting an exchange sacrifice from White. 15...0-0 16.Rxa4 a5 is the current preference, but we’ll see in Ganguly-Shirov, Edmonton 2016 that 17.h4! Bh6 18.b5 puts pressure on Black. 16.Bxa6 0-0 17.0-0 Bc6 17...Qe8!? was recently played by Dubov, avoiding the exchange sacrifice: 18.b3 axb3 19.Qxb3 Kh8 20.Bc4 f5 21.exf5 Bxf5 22.b5 Bd8 (22...Qg6!? is also fully playable for Black, though the assessment remains the same after 23.Ra2 Bd8 24.Qg3²) 23.Qa3!? Qd7 24.Rad1² White can’t claim an objective advantage, but in my view the passed b-pawn offers enough scope to play for a win without any risk. 18.Rxa4! Bxa4 19.Qxa4 In a similar vein to Negi’s recommendation against the Sveshnikov, the engines give a 0.00 evaluation, but a quick look at the position (and correspondence games) shows that White is the one pressing here, as Black lacks a way to utilise his exchange. 19...Kh8 The game Nekhaev-Rost, email 2009, is a good demonstration of the computer’s weakness in such positions. A) 19...g6 20.Qc6 Qe8 21.Qxe8 Rfxe8 22.b5 f5 23.exf5 gxf5 24.b6 and modern engines only give White a tiny edge, when in fact the endgame is close to winning; B) 19...Qe8 20.Qxe8 Rfxe8 21.b5 is covered in Anand-Van Wely, Wijk aan Zee 2006, though I think 21.g3!² is a slight refinement; C) 19...f5 is a likely response over the board, as most players do not like to sit and wait passively. But after 20.exf5 Rxf5 21.b5 the game Timmerman-Boger, email 2006, proves that White is already better. The attempted improvement 21...Qe8 22.Qe4 g6 doesn’t change things after 23.b6 Kg7 24.Qc4 e4 (Dauga-Bösenberg, email 2010) 25.Re1! Qf7 26.Qc3+ Re5 27.Bc4! with positional control. 20.b5! We shouldn’t fear our bishop being stuck, as it supports b6-b7 and keeps Black’s rooks out of the game. 20...Qd7 21.Qc4 Bd8 21...f5 22.exf5 Bd8 (this move order gives a strange appearance; 22...Qxf5 23.b6 e4 24.b7² is White’s dream scenario, as explicated in Chocenka-Hebels, email 2008) 23.Qc6 Qxf5 24.b6 Bh4 25.g3 Qf3 26.b7 Bg5 Boger held two draws in correspondence games after 27.Nb4, but a possible refinement is 27.b4!? Bd2 28.Qc4 when Black does not have an easy way to make a draw, while White can keep improving his position. For example, 28...Be1?! is tricky but well met by 29.Qa2! Qd1 30.Ne7 Rxf2 31.Rxf2 Bxf2+ 32.Kg2! Qg1+ 33.Kh3 Bxg3 34.hxg3 Qh1+ 35.Qh2±. 22.Qc6 Qa7! 22...Qxc6 23.bxc6 Rxb2 24.c7 Bxc7 25.Nxc7 Rfb8 26.Nd5 g6 has led to all draws in correspondence, but I doubt many players would enjoy the task of holding Black’s position after 27.g4! Kg7 28.g5 h6 29.h4². 23.Qxd6 Re8 Correspondence play and computers confirm that because of Black’s dark-squared blockade, White has no advantage. But... 24.g3 Bb6 25.Kg2 Bd4 26.Qc7 Qxc7 27.Nxc7 Re7 27...Red8?! 28.b3 g6 29.Rc1² already looks a bit better for White. 28.Nd5 Rd7 29.b3 f5 30.f3= White is also not risking anything, and with Rc1-c6 still has some potential to outplay a weaker player. From this overview, we can understand why most of the world’s top players currently prefer 3.Bb5 against 2...Nc6, but my recommendation allows us to prove an advantage against all but the most precise defence by Black, without giving Black any winning chances. Summary 5...e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3: 8...Be6 9.Nc4 – +0.35 8...b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3: 11...Bb7 – +0.40 11...Ne7 – +0.40 11...0-0 12.Nc2 Rb8 – +0.30 11...Bg5 12.Nc2: 12...Ne7 – +0.30 12...0-0 – +0.30 12...Rb8 – +0.10 5.1 Tadeusz Baranowski 2491 Arkadiusz Zlotkowski 2448 ICCF email 2010 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 Be6 9.Nc4 Rc8 10.Nd5 Bxd5 11.Bxf6 gxf6 12.Qxd5 Nd4 13.Bd3 b5 14.Ne3 Bh6 15.c3 Bxe3 16.fxe3 Ne6 17.0-0² Ke7 After 17...Qb6 18.Rxf6 Qxe3+ 19.Kh1 0-0 20.Rf3 Qc5 surprisingly White has spurned 21.Qb3!N 21...Nf4 22.Raf1 Rcd8 23.Qd1 Kh8 24.Bc2 d5 25.exd5 Qxd5 26.Qb1!ƒ with the far safer king. 18.Bb1 A strange square for the bishop; I would favour 18.Bc2 Qb6 19.Qd2 Rhg8 20.Bb3 (or 20.a4 bxa4 21.Rxa4 a5 22.Ra2 Rg6²) 20...a5 21.a3 a4 22.Ba2 Rg6 23.Kh1 Rcg8 24.Rf2². Perhaps the engine could sit on Black’s position, but I would not volunteer for the task. 18...Qb6 19.Qd2 Rhg8 20.a4 Rg4 21.Qf2 Rg6 22.axb5 Qxb5 22...axb5 23.Ra3 Rcg8 24.Kh1 Qb7 25.b4ƒ 23.Ba2 23.Kh1 Nc5! initiates annoying counterplay. 23...Rcg8 24.g3 24.Kh1 Nc5 25.Bd5 Nd3 26.Qf3 Qxb2= 24...h5 25.Kh1 White’s play has been a bit indecisive, and Black now has full kingside counterplay. 25...h4 25...Rh6 26.Qf3 h4 27.Bxe6 fxe6 28.gxh4 Rgg6 29.Rg1 Qxb2 30.h5 Rxg1+ 31.Rxg1 Rh7= 26.gxh4 Rh6 27.Bxe6 fxe6 28.Rg1 Rxg1+ 29.Qxg1 Rxh4?? It seems Black mixed up his move order. 29...Kf7 30.Qg2 Rg6 31.Qc2 Qc4 should be a draw, as White’s king is too open. 30.Qg7+ 1-0 5.2 Yuri Kryvoruchko 2693 Eduardo Iturrizaga Bonelli 2650 Spain tt 2016 (4) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 e5 5.Nb5 d6 6.N1c3 a6 7.Na3 Nf6 8.Bg5 Be6 9.Nc4 Rb8 10.Nd5 Bxd5 11.exd5 Ne7 12.Bxf6 gxf6 13.a4 f5 14.a5 Bg7 15.g4 Black will lose the battle for the light squares. 15...f4?! A) 15...Rc8 16.gxf5 Rc5 17.Qf3 Bh6 18.b4! Rc7 19.Bd3±; B) 15...0-0 16.gxf5 Nxf5 17.Rg1 Nh4 18.Qh5!? (this in conjunction with Ra3-h3 gives White a strong attack; 18.Qg4 Ng6 19.Bd3²) 18...e4 (18...Ng6 19.Ra3!) 19.Ra3 Nf3+ (19...Qf6 20.Be2) 20.Rxf3 exf3 21.Bd3 f5 22.Bxf5 Qe8+ 23.Be6+ Kh8 24.Qxe8 Rbxe8 25.Nxd6 Re7 26.Nc4² 16.Bg2 The ideal configuration is 16.Qf3!? 0-0 17.Bd3ƒ. 16...Rc8 17.Qd3 Rc5 18.Be4! Qc7 19.b3± 19.Nb6! has the cute point that 19...Nc8?! 20.Na8! and b3-b4 wins the exchange. 19...h6 20.Kd2 0-0 21.h4? 21.Ra4 stops all the tricks. 21...Nc6! 22.g5 22.dxc6 d5! 23.Bxd5 Rd8 22...h5? A failed attempt to close the kingside. Black had to play 22...Nxa5! 23.Nxa5 Rxa5 24.gxh6 Bxh6 25.Rag1+ Kh8 26.Rg5 f5! when the king stays guarded: 27.Bxf5 Qc5 28.Ke2 Qxd5 29.Qxd5 Rxd5= 23.Qf3 Nxa5 24.Nxa5 Rxa5 25.Qxh5+– White is effectively up a bishop for his attack. Black resigned on move 35. 5.3 Viktor Zakharov 2341 Drahoslav Masarik 2337 ICCF email 2010 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Qa5+ 10.Bd2 Qd8 11.Bd3 Nxd5 12.exd5 Ne7 13.c4² Black’s sad score explains why this variation is virtually unseen today. 13...g6 13...bxc4? 14.Nxc4 turns White’s rim knight into a beast! 14...Ng6 (14...Nxd5 15.Ba5 Nc7 16.Rc1+–) 15.Ba5 Qg5 16.Nb6 Rb8 17.Rc1 Qd8 18.b4+–. It would be too optimistic to play 13...f5? 14.cxb5 Nxd5 15.bxa6 Nf6 16.Rc1+–. 14.cxb5 Bg7 15.0-0 0-0 16.Bc4! White should retain his grasp of the centre. 16.Bb4? Nxd5! 17.Be4 Nxb4 18.Bxa8 d5 19.Qd2 Qe7 20.b6 Be6 with counterchances. 16...e4 16...f5 17.Qa4! Bd7 (17...Qd7 18.b3) 18.Qb4 f4 19.bxa6 Nf5 20.Nc2 Qg5 21.f3± puts a halt to Black’s attack. 17.Qc2 Nf5 17...Bb7!? 18.Rfe1 Bxd5 19.Bxd5 Nxd5 20.Qxe4² 18.Rfe1!? I would prefer to trade Black’s one active bishop, but this is also fine. 18.Bc3 Bxc3 19.Qxc3 axb5 20.Nxb5 Ba6 21.a4² Boschma-Thierry, email 2008. 18...Qb6 19.Rxe4 19.Bc3! Bxc3 20.Qxc3± 19...Nd4 20.Qd1 Bf5 21.Rf4 axb5 21...Nxb5!? might already be the last chance to avoid defeat. 22.Bc3! Ne2+ 23.Qxe2 Bxc3 24.bxc3 Rxa3 25.Bxb5 Qa5 26.Qb2 Rxc3 27.a4± It is difficult to save the game against an extra outside passed pawn, supported by the rook behind it! 27...Rb8 27...Rc2 28.Qb4 Qxb4 29.Rxb4 Rb8 30.a5 Bc8 31.Bd3 Rxb4 32.Bxc2 Ba6 33.Rb1 Rxb1+ 34.Bxb1+– 28.h3 Bd7 29.Rb4 Rc7 30.Kh2 Rc5 Better was 30...Bf5. 31.Rb1 Bxb5 32.Rxb5 Rcxb5 33.axb5+– h5 34.f4 Qa4 35.Qb4 1-0 5.4 Sergey Kudrin 2550 Javier Ochoa de Echaguen 2405 New York 1992 (9) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 Bb7 12.Nc2 Bg5 13.a4 bxa4 14.Rxa4 Nb8 14...0-0 15.Bc4 Na5 16.Ba2 Bc6 17.Ra3 Bb5 is an abnormal manoeuvre, against which we can follow Ould AhmedDurandal, email 2009: 18.h4! Bh6 19.Nce3 Bxe3 20.Nxe3 Rc8 (possibly best (but passive) is 20...Nb7 21.Bd5 Rb8 22.c4 Bd7 23.Qd2!?±) 21.h5 Nc4 22.Bxc4 Bxc4 23.h6 g6 24.Nxc4 Rxc4 25.Qd3 Qc8 26.0-0 Qc6 27.Rd1 Rd8 28.Ra5! Qxe4 29.Rxa6+– 15.Bc4 15.h4! Bh6 16.Nce3 Bxe3 17.Nxe3± and Nf5/Qg4 is a deft play. 15...Nd7 16.Qe2 0-0 17.0-0 a5 18.Rfa1 Nc5 18...g6 19.R4a2 Kg7 keeps a solid position, but White can intensify the pressure with 20.Na3!?² and Nb5. 19.R4a2 a4 20.Ncb4 Rb8 21.Rd1± Kh8 21...Qc8 22.Bb5 Bxd5 23.Rxd5± 22.Bb5 22.Nd3!? 22...f5 23.exf5 Rxf5 24.Bxa4 e4 This splits the structure, but 24...Nxa4 25.Rxa4 Rf7 is still bad for Black. 25.Bc6! Bc8 26.Rda1+– Nb3 27.Ra8! Rxa8 28.Rxa8 The back-rank pin is unbearable. 28...Nc5 29.Qc2 Even better was 29.Nb6. 29...Nd3 30.Nxd3 exd3 31.Qxd3 Rf7 32.b4 Qg8 33.Nb6 1-0 5.5 Ara Minasian 2479 Baris Esen 2420 Moscow 2006 (6) 1.e4 c5 2.Ne2 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 Ne7 12.Nxf6+ gxf6 13.Nc2 Bb7 14.Bd3 d5 15.Qe2 f5 16.exf5 e4 17.f6 Ng6 18.Qe3 Qxf6 19.g3± b4!? 11...Ne7 players tend to solve a hundred tactical puzzles before breakfast, so we should be careful. 20.Be2! 20.Nxb4? d4! 21.cxd4 Qe7 is a painful trick. 20...bxc3 21.bxc3 0-0 22.Rb1 22.0-0 Rac8 23.Nd4² 22...Bc8 23.0-0 Bh3 24.Rb6?! The active move, but for tactical reasons White should precede it with 24.Rfd1 Be6 25.Rb6±. 24...Qe5? 24...d4! 25.Rxf6 dxe3 26.Rc1 exf2+ 27.Kxf2 Ne5² 25.f4! 25.Rd1 25...Qc7 26.Rf2? White wants to play on the kingside, but he should have focused on the queenside: 26.Rfb1 26...Ne7 27.g4 f5! 28.g5 Bg4 29.Bxa6 Rfb8 30.Rxb8+ Rxb8 Suddenly White must be exact, because of his open king. 31.Nb4 31.Nd4 31...Bh5 31...Qd6! 32.Qd4 Bf3= 32.Bf1 32.a4! 32...Rc8 33.Rc2 Bf7= The rest of the game was a scrappy affair. Black got himself mated on move 54. 5.6 Daniel Alsina Leal 2517 Adria Martorell Aubanell 2159 Sabadell 2008 (4) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 Ne7 12.Nxf6+ gxf6 13.g3 Bb7 14.Bg2 d5 15.exd5 Bxd5 16.Bxd5 Qxd5 17.Qxd5 Nxd5 18.0-0-0 0-0-0 19.Nc2 Rd7 20.Rhe1 Rhd8 21.Rd3 Ne7 22.Rxd7 Rxd7? 22...Kxd7 23.a4² 23.Re4!± The Spanish GM’s endgame handling from here is exemplary. 23...Ng6 24.Ne3 Kc7 25.a4! Inducing further weaknesses in Black’s camp. 25...Kd6 26.Kc2 Rb7 27.axb5 27.Nf5+!? Ke6 28.Ng7+ Kd6 29.axb5 axb5 30.Re1± 27...axb5 28.f4 28.Nf5+! Kc5 29.Re3± is more precise, preparing Rf3 or Rd3. 28...exf4 29.gxf4 Rb8? 29...Rd7! 30.Rd4+ Kc6 31.Rxd7 Kxd7 32.f5 Nf4² and the knight endgame is not so easy for White to win, due to Black’s active knight. 30.Rd4+ Kc6 31.Nf5 Re8?! 31...Kc7± 32.Rd6+ Kc7 33.Rxf6 Re2+ 34.Kb3 Rxh2 35.Nd4+– Now Black will haemorrhage pawns. 35...Rh5 36.Rxf7+ Kb6 37.Kb4 Rh2 38.b3 Rf2 39.Rf6+ Kb7 40.f5 Nf4 41.Kxb5 1-0 5.7 Jean Claude Schuller 2381 Gordon Dunlop 2450 ICCF email 2014 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 00 Funnily enough castling is probably not the best move here! 12.h4!? A favourite of correspondence GM Siigur. 12.Nc2 Rb8 13.h4 12...Rb8 A) 12...g6 13.g3 Bg7 14.Nc2 Ne7 15.Nce3 h5 16.Be2 Nxd5 17.Nxd5² Schlenther-Killer, email 2011; B) 12...Be6 13.Nc2 Bxd5 14.Qxd5 Ne7 15.Qd3²; C) 12...Ne7!? 13.Nxf6+ gxf6... ... is a creative try, but I prefer White in the arising ending: 14.Nc2 d5 15.exd5 Qxd5 16.Qxd5 Nxd5 17.0-0-0 Be6 18.g3 Kg7 19.Bg2 Rad8 20.Rhe1 as his structure is preferable. 13.Nc2 a5 14.Nce3 b4 14...Be6?! 15.Nxf6+ Qxf6 16.Qxd6 Rfc8 17.Be2± 14...Be7 15.a4! b4 16.Bb5 Na7 17.cxb4 Nxb5 18.axb5 axb4 19.b6± 15.Bc4 15.g3 15...Kh8 15...bxc3 16.bxc3 Be6 17.g3 Bxd5 18.Qxd5! Ne7 19.Qd3± 16.g3 g6 Creating a hook, but otherwise one wonders where the f6-bishop is going. 17.Bb3! Bg7 18.h5ƒ Black has avoided the undermining of his queenside, but now feels the heat on the kingside. 18...h6 19.Qd2 Be6 20.Rd1 20.hxg6?! bxc3 21.bxc3 fxg6 22.Nf5 h5 23.g4 a4! 24.Bxa4 Bxd5 25.Nxg7 Kxg7 26.exd5 Na5 27.gxh5 Nc4 28.Qc2 Qg5 29.Bb3 Na5 30.Qxg6+ Qxg6 31.hxg6 Nxb3 32.axb3 Rxb3² looks like a draw with best play, due to the reduced pawns. 20...bxc3 21.bxc3 Rb7 22.Kf1 Nb8 23.Kg2 Na6 24.Nc4 Nc5 25.Bc2 a4 26.Qc1 26.f3!? 26...g5?! The course of the game indicates this is a strategic mistake. Black had to lash out with 26...f5! 27.hxg6 f4 28.Rh2 Qg5 29.Nxd6 Rd7 30.Nf7+ Bxf7 31.gxf7² with a tense position, but White has an extra pawn as insurance. 27.Rhe1 Qb8 28.Qe3 a3 29.Rd2 Rc8 30.Nxa3 Bf8 31.Nc4± Qa7 32.Bb3 Kg7 33.Nb4 Nxb3 34.Qxa7 Rxa7 35.axb3 Bxc4 36.bxc4 Rxc4 37.Nd5 Black’s bishop is so dominated that it’s hard to see him surviving for the long haul. White won on move 58. 5.8 Sergey Karjakin 2694 Alexei Shirov 2739 Heraklion Ech-tt 2007 (2) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 00 12.Nc2 Rb8 13.h4 Be7 14.g3 Be6 15.a3 a5? An instructive positional mistake. A) 15...Rb7 16.Ncb4 (16.Nce3 Qd7 17.f4!? exf4 18.gxf4 a5 19.h5 h6 20.Qd2 Bd8 with counterchances) 16...Nb8! leaves White’s knights treading on each other: 17.Ne3 Qd7 18.Bg2 (18.Be2!?) 18...Bd8 19.Nbd5 Nc6 20.0-0 Ne7=; B) 15...Qd7 16.Ncb4 Nxb4 17.axb4 Ra8 18.Bg2 Bd8 19.0-0 Qc6 20.Ra3 Ra7 has exclusively been drawn in practice. 16.Nce3 Re8 16...Qd7 17.a4! bxa4 18.Qxa4 Rxb2? 19.Qxc6+–; 16...a4 fixes b5 as a weakness after 17.Bd3±. 17.a4! This is the problem! Now Black loses the queenside battle. 17...b4 18.Bb5 Bd7 19.0-0 bxc3 20.bxc3± Bf8 21.Qd3 Na7?! 21...Re6 was more resistant. 22.Bxd7 Qxd7 23.Qa6 23.Nc4! 23...Nc6 24.Rab1+– Red8 25.Rb6 Rxb6 26.Nxb6 Qa7 27.Qxa7 Nxa7 28.Nbc4 Rc8 29.Rb1 Rc5 30.Rb8 g6 31.Ra8 Nc6 32.Nb6 Black resigned. 5.9 Janos Percze 2545 Pertti Raivio 2451 ICCF email 2011 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 00 12.Nc2 Rb8 13.h4 Be7 14.Nce3 Be6 15.a4 Qd7 16.axb5 axb5 17.Be2 Bd8 18.h5 h6 19.0-0 Bg5 20.Ra6² 20...Rfd8 A) 20...Kh8 21.Qa1 Bxe3 22.Nxe3 Rfd8 23.Rd1 Bb3 24.Rd2 Qb7 25.Ra3 Be6 26.b4!± fixed Black’s weaknesses in Riccio-Lanc, email 2008; B) 20...Bxe3! 21.Nxe3 (21.Rxc6 Kh8 22.Ra6 Ba7 23.Qd2 f5 24.Rfa1 Rb7 25.exf5 Bxf5 26.Ne3²) 21...Qb7 22.Ra1 Rfd8 23.Bg4 b4 24.Bxe6 fxe6 – here Black has drawn all the email games, but OTB White can ‘play for two results’ at his leisure, e.g. 25.Qg4 Qe7 26.Ra6 Rbc8 27.Rfa1 bxc3 28.bxc3 Rc7 and now the novelty 29.g3!?². 21.Qd3 Ne7 22.Nxe7+ Qxe7 23.Nd5 Qb7 24.Rfa1 f5 25.Rb6 fxe4 25...Qf7 26.Rxb8 Rxb8 27.Nb4 Rf8! 28.exf5 Bc4 29.Qe4 Bxe2 30.Qxe2 Qxf5 31.g3!?² keeps Black’s kingside play covered. 26.Qxb5 Qc8 27.Bc4 Rxb6 28.Nxb6 Bxc4 29.Qxc4+ Qxc4 30.Nxc4 Black’s structure is questionable and his bishop remains passive. 30...Bf6 31.Nb6 d5 32.c4! dxc4 33.Nxc4 Black subsequently played the engine’s first line on every move, yet ended up in a lost position. 33...Rd4 34.b3² Rd3 35.Rb1 Be7? 35...Rd4! was a better try, though 36.Kf1 and Ke2 still gives excellent winning chances, as White is effectively a pawn up. 36.Kf1 Bb4 37.g4! Bc3 38.Ke2 Kf8 39.Rg1 Ke7 39...Bd4 40.Rg3 Rxg3 41.fxg3+– 40.Rg3! Rxg3 41.fxg3+– The knight overwhelms the bishop on a narrow battlefield. 41...Ke6 42.Ne3 Bd4 42...Bb4 43.g5! hxg5 44.g4+– 43.g5 hxg5 44.g4 Bc5 45.Kd2 Bb4+ 46.Kc2 Bf8 47.Kc3 Kf7 48.Nc4 Bc5 49.b4 Bd4+ 50.Kd2 Ke6 51.Ke2 e3 52.Nxe3 e4 53.b5 Bc5 54.Nf5 Kf6 55.Kd1 Bb6 56.Nd6 Ke6 57.Nxe4 1-0 5.10 Denyam Lauth Oliveira 2579 Valery Myakutin 2423 ICCF email 2011 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 00 12.Nc2 Rb8 13.h4 Be7 14.Nce3 Be6 15.a4 Qd7 16.Be2 Bd8 17.axb5 axb5 18.h5 Bg5 19.0-0 Rfd8 20.b4 Ne7 21.Qd3 Bxe3 22.Nxe3 d5 23.exd5 Nxd5 24.Nxd5 Bxd5 25.Rfd1 A) 25.Qg3 Qc6 26.Ra7 h6 27.Rfa1 Re8 28.R1a5!?N 28...Rb6 29.Qh3² keeps Black tied down to b5; B) 25.h6!? Qc6 26.Rfd1 Qf6 27.Qh3! Qxh6 28.Qxh6 gxh6 29.Ra5ƒ picks up the b5-pawn. 25...h6 26.Ra5! 26.Rd2 Bc6 27.Qxd7 Rxd7 28.Rxd7 Bxd7 29.Ra7 Be8 30.Kf1 Kf8 31.Rc7 f6² 26...Qe8 Better was 26...Bc6. 27.Qg3 Bc6 28.Rxd8 Rxd8 29.c4 Qe7 30.c5² Qe8 31.Qc3 Better was 31.Ra6. 31...Qe7 32.Bf1 Rd1?! The resultant exchange of pieces favours White. Black had to essay the combative 32...Qg5! 33.Ra6 Bxg2! 34.Bxg2 Rd1+ 35.Kh2 Qh4+ 36.Qh3 Qxf2 when the exposed king makes a repetition inevitable, a case in point being 37.Qf3 Qh4+ 38.Qh3 Qf2=. 33.Ra1 Rxa1 34.Qxa1 e4 35.Qd4± Perhaps Black is not lost yet, but he was unable to save the game (1-0, 63). 5.11 Sergey Karjakin 2635 Teimour Radjabov 2673 Warsaw Ech 2005 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 Bg5 12.Nc2 Ne7 13.h4 Bh6 14.a4 bxa4 15.Ncb4 Bd7?! 16.Rxa4! Nxd5 17.Nxd5 Bxa4 18.Qxa4+ Kf8 19.b4² We’ll see other exchange sacrifices, but this is the best version as Black has also lost the right to castle. 19...a5 19...Qc8 20.Be2 g6 21.0-0 Kg7 22.Ra1 Rf8 23.g3! was still undesirable for Black in Rebord-Rocca, email 2011. 20.b5 Rb8 21.g3! g6 22.Bh3 Kg7 23.0-0 Rf8 24.Ra1 Kh8 25.Qxa5 Qe8?! 25...Qxa5 26.Rxa5 Ra8 27.Rxa8 Rxa8 28.Kf1 gives White realistic winning chances, but nothing is settled. 26.c4± f5 27.Qc7! Now Black’s open position is a concern. 27...Qf7 28.exf5 28.Qxd6! fxe4 29.Rf1± 28...Qxc7 29.Nxc7 gxf5 30.Ra6!ƒ White’s domination continues into the endgame. 30...Rf7? Better was 30...Rbc8 31.Ne6 Rf6. 31.Nd5 31.Ne6! 31...Bf8 32.Rc6 f4?! 32...Kg7 33.Be6 Rg7 34.g4+– Re8 35.Bf5 Be7 36.h5 Bg5 37.b6 e4 38.Rc8 Rxc8 39.Bxc8 e3 40.fxe3 fxe3 41.b7 1-0 5.12 Martin Müller Alves 2344 Pedro Pablo Taboada 2228 LSS email 2008 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 Bg5 12.Nc2 Ne7 13.h4 Bh6 14.a4 bxa4 15.Ncb4 0-0 16.Qxa4 a5 17.Bb5 Nxd5 18.Nxd5 Kh8 19.b4 f5 20.Bc6 Ra7 21.b5 fxe4 22.Qxe4 Raf7 23.0-0 Bf5 23...Be6?! 24.b6!± 24.Qc4 Be6 25.Qa4 Bd2?! 25...Bf4! 26.g3 Qc8 27.Qe4 Bf5 28.Qe2 Bh6 In Kain-Bastos, email 2012, White took on a5, but it’s more important to keep control with 29.f3! Be6 30.c4 Bxd5 31.Bxd5 Qh3 32.Qh2 Be3+ 33.Kh1 Qxh2+ 34.Kxh2 Ra7 35.Rae1 Bb6 36.f4!± and Black is facing central bombardment. 26.b6! Bxd5 27.Bxd5 Rf5 28.Qc2 Bf4 29.g3 Qxb6 30.Rfb1 Qd8 31.Rxa5 Qxa5 32.Qxf5 Qd8 33.Qd3 Bh6 34.Kg2± Such opposite-coloured bishops positions are frequent and welcome in our repertoire. 34...Qa5 34...g6!? at least tries to reroute the bishop. 35.Rb5 Qa3 36.h5! Qa7 37.Bf3+– Qc7 38.c4 Bg5 39.Rb7 Qd8 40.Be4 Qf6 41.f3 Qh6 42.Rd7 Rd8 43.Rxd8+ Bxd8 44.c5 Bc7 45.Qb5 Qe6 46.Qb7 Qd7 47.c6 Qd8 48.Bd5 Qb8 49.Qxb8+ Bxb8 50.Kh3 Bc7 51.Kg4 g6 52.h6 Bd8 53.f4 exf4 54.Kxf4 Ba5 55.Ke4 1-0 5.13 Peter Leko 2753 Magnus Carlsen 2733 Morelia/Linares 2008 (11) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 Bg5 12.Nc2 Ne7 13.h4 Bh6 14.a4 bxa4 15.Ncb4 0-0 16.Qxa4 Nxd5 17.Nxd5 a5 18.Bb5 Be6 19.Bc6 Rb8 20.b4 Bxd5 21.Bxd5 axb4 22.cxb4 Qb6 23.Rb1 Kh8 24.0-0 24...f5! 24...Bd2 25.b5 Bc3 26.g3 Bd4 27.Kg2 f5 28.exf5 Rxf5 29.f3 Rff8 30.Rfc1 Bc5 31.Qc4 Qd8 32.Ra1± was played in two correspondence games, and in neither was Black able to save the draw. 25.Qa5 25.Qc2!? fxe4 26.Bxe4 Rbc8 27.Qd3 Rf6 28.Bf3 g6 29.b5± showed that the middlegame is also not easy for Black to defend, Dorer-Portych, email 2013. 25...fxe4 26.Qxb6 Rxb6 27.Rb3!² White’s passed b-pawn won’t win by itself, but it ties Black up against other attempts. 27...Rc8?! 27...Rfb8 28.Rfb1 g6 29.b5 Rc8² seems best, forcing the pawn ahead to assist with the dark-squared blockade. 28.Ra1! g6 29.Ra8 29.b5!? could have been played initially. 29...Rxa8 30.Bxa8 Bf8 31.b5 Be7 32.g3 Bd8 33.Bxe4 d5?! Eight years after this game, Carlsen famously stated ‘I don’t believe in fortresses.’ But in this case, 33...Kg7 34.Bc6 Rb8 35.g4 Bb6² and ...Rf8 would work. 34.Bxd5 Rd6 35.Bc6± The extra pawn is a big boost to White’s winning chances, and one can count on Leko to close. Black resigned on move 62. 5.14 Viswanathan Anand 2779 Teimour Radjabov 2729 Monaco blind 2007 (2) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bf4 e5 8.Bg5 We have a Sveshnikov, but with one extra move played to get here. 8...a6 9.Na3 b5 10.Nd5 Be7 11.Bxf6 Bxf6 12.c3 Bg5 13.Nc2 0-0 14.a4 bxa4 15.Rxa4 a5 16.Bc4 Bd7 17.0-0 Not the best move, but Black often plays inaccurately in human games. A) 17.h4 Bh6 18.Nce3 Ne7 19.Nxe7+ Qxe7 20.Nd5 Qd8 21.Ra3 a4! 22.Nb4 Qb6 23.0-0 Kh8=; B) 17.Ra2 a4!? and ...Na5 is annoying; C) 17.Nce3! looks like the way to prove a white edge: 17...Ne7 18.Nxe7+ Qxe7 19.Nd5 Qd8 20.Ra2 a4 21.0-0 Rb8 The last moves were obvious, but now White needs to reorganise his pieces to attack a4 and d6. 22.Bd3! Qc8 23.Nb4 Bd8 (23...h6 24.Bc2 Bg4 25.f3 Be6 26.Rxa4 Be3+ 27.Kh1 Bc5 28.Nd3 Qc7 29.Qe2± doesn’t give Black a lot for the pawn, Mahling-Pirs, email 2012) 24.Bc2 Ba5 25.Nd5 Qc4 26.Qa1 Bb6! (26...Bd8 27.Rd1±) 27.Bxa4!?N (27.Re1 Qc5!= was Ivanov-Staroske, email 2012) 27...Be6 28.Bc6 Kh8 29.Nxb6 Qxc6 30.Nd5 Bxd5 31.exd5 Qxd5 32.Rd1 Qc6! 33.Ra6 Rb6 34.Rxb6 Qxb6 35.Qa3 Rd8 36.b4 This position has virtually been analysed to death by the machines, but in a practical game White’s outside majority gives him the upper hand. 17...Nd4? 17...Nb4! is important, to loosen White’s grip over d5: 18.Ra3 Nxd5 19.Bxd5 Rb8 20.b4 axb4 21.Nxb4 Qc8! with a lot of draws in correspondence, as c3 and d6 balance each other. 18.Ra2 Ne6 19.Qe2!² White wants two weaknesses to target. 19.b4!? axb4 20.Rxa8 Qxa8 21.cxb4² 19...a4 20.Ncb4 20.Na3! is more harmonious, threatening 21.Nb5. 20...Nc5 20...Kh8 21.Nd3 21.Na6! 21...Ne6 22.Rfa1 22.g3 22...Rc8 22...Rb8! 23.N3b4 Nc5?! 24.Bb5! Now we understand why the rook belonged on b8. 24...Bxb5 25.Qxb5ƒ Kh8 26.Na6 Nxe4 27.Nb6± Rxc3? Desperation, but 27...Qe8 28.Qxe8 Rcxe8 29.Nc7 Rd8 30.Rxa4± should also win with best play. 28.Rxa4+– f5 29.bxc3 Nxc3 30.Qc6 Nxa4 31.Rxa4 Black plays on in the hope of a blindfold blunder, but none came and White won on move 46. 5.15 Viorel Craciunescu 2511 Jan Bennborn 2518 ICCF email 2008 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 00 12.Nc2 Bg5 13.a4 bxa4 14.Rxa4 a5 15.Bc4 Rb8 16.b3 Kh8 17.Nce3 Be6 18.h4 Bxe3 19.Nxe3 Bxc4 A) 19...Qb6!? 20.0-0 Bxc4 21.Rxc4 Ne7 22.b4! axb4 23.Rxb4 Qc6 24.Qd3 Rxb4 25.cxb4 Rb8 26.Rb1± and the b-pawn beats the d-pawn, hands down; B) 19...Ne7 20.0-0 Bc8 21.Ra2!? f5 22.exf5 Nxf5 23.Nxf5 Bxf5 24.Re1² is probably Black’s best line, but here too he will be suffering for half a point. 20.Nxc4 f5 21.Nxd6 Qf6 21...fxe4 22.Nxe4 Qxd1+ 23.Kxd1 Rxb3 24.Kc2 Rfb8 25.Ra2± keeps Black restrained. 22.Qd5! Rbd8 23.Qxc6 Rxd6 24.Qc5 White’s neutralising of Black’s activity from here is faultless. 24...Rc6 25.Qe3 f4 26.Qf3 Qd8 27.h5 Rd6 28.Ra1! Rd3 29.Rd1 Rxf3 30.Rxd8 Rxd8 31.gxf3 Rb8 32.Kd2 Rxb3 33.Kc2 Rb8 34.Ra1 Ra8 35.Kb3± White is a king up in the endgame! 1-0 (56). 5.17 Peter Leko 2753 Teimour Radjabov 2735 Morelia/Linares 2008 (1) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 00 12.Nc2 Bg5 13.a4 bxa4 14.Rxa4 a5 15.Bc4 Rb8 16.b3 Kh8 17.Nce3 Bxe3 18.Nxe3 Ne7 19.0-0 f5 20.exf5 Bxf5 21.Ra2² 21...Be4 A) 21...h6 22.Re1 Qb6 23.Qa1 Be4 24.Rxa5 d5 25.Bf1 Qxb3 26.c4 Nc6 27.Ra3 Qb4 28.Ra4 Qb3 29.cxd5 Nd4 30.Qa2± was one pawn more in Ottesen-Schwenck, email 2008; B) 21...Rf6 22.Re1 Be6 23.Bxe6 Rxe6 24.Nd5 h6! 25.h3 Nxd5 26.Qxd5 Re7 27.Re3 Reb7 28.Rxa5 Rxb3 29.Ra7² placed Black’s kingside under duress in Broudin-Offenborn, email 2013. 22.Rd2 Rb6 23.Re1! 23.Qa1!? Rb8 24.Qa3 d5 25.Rfd1 Qc7 26.Nxd5 Bxd5 27.Bxd5 Nxd5 28.Rxd5 Qxc3 29.Qxa5 Qxa5 30.Rxa5 Rxb3 31.Rxe5 Rb2² is a defensible endgame. 23...Qb8 24.Qa1 Qc7 24...Qb7?! 25.Qa3! 25.Red1 Black tries to wait around from here, but that’s not feasible with two weaknesses to protect. 25...h6 25...d5!? 26.Nxd5 Bxd5 27.Bxd5 Nxd5 28.Rxd5 Rxb3 29.Rxa5 Rxc3 (29...Qxc3 30.Ra8! Qc5 31.Rxf8+ Qxf8 32.Qxe5±) 30.Ra8 Rg8 31.Rxg8+ Kxg8 32.Qa2+ Kf8 33.h4!± 26.h3 26.Qa3!? 26...Bb7? It was time to bail out with 26...d5! 27.Bxd5 Bxd5 28.Nxd5 Nxd5 29.Rxd5 Rxb3 30.Qxa5 Qxa5 31.Rxa5 Rb2!? 32.Rf1 Re2 and the passive f1-rook should help Black to save the game. 27.Qa3!± Rd8 28.Be6 Qxc3 28...d5 29.Bxd5 Rxd5 30.Rxd5 Bxd5 31.Nxd5 Nxd5 32.Rxd5 Qxc3 33.Qf8+ Kh7 34.Qf5+ Rg6 35.g3! Qc1+ 36.Kh2 Qc6 37.Rxe5± 29.Rxd6 Rbxd6 30.Rxd6 Black’s position collapses with the d6-pawn. 30...Qe1+?! 30...Qc7 31.Rxd8+ Qxd8 32.Qc5± wins a pawn, but some technique is still called for. 31.Kh2 Re8 31...Rxd6 32.Qxd6 Qb4 33.Qxe5+– 32.Rd7+– White wins a piece. 32...Nc6 33.Bf7 Ra8 34.Rxb7 Qxf2 35.Bd5 Rc8 1-0 5.18 Anish Giri 2768 Alexei Shirov 2691 Hoogeveen 2014 (6) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 Bg5 12.Nc2 0-0 13.a4 bxa4 14.Rxa4 a5 15.Bc4 Rb8 16.b3 Kh8 17.Nce3 g6 18.h4! Bxh4 It is a bit late to bail out with 18...Bxe3 19.Nxe3 Ne7 20.h5ƒ (Dzenis-Kevicky, email 2005) though that may well be the objectively best decision. 19.g3 Bg5 19...Bf6 20.Ra2! Bg7 21.f4 exf4 22.gxf4 Re8 23.Rah2 h6 24.Kf2 Kg8 25.Nf5! Bxf5 26.exf5, as played in Peli-Satici, email 2008, refutes the attempt to avoid f2-f4 with tempo. 20.f4 exf4 21.gxf4 Bh4+ 22.Kf1! It is paramount to leave the 2nd rank clear for Ra2-h2. 22...f5 22...g5 is the one line where we’ll delay Ra2-h2: 23.Qh5! f6 24.Ng2 Rb7 25.Nxh4 gxh4 26.Qxh4ƒ and ‘regaining the pawn with interest’ would be putting it mildly. (26.Rxh4!? is messier but might be even stronger) 23.Ra2! fxe4 24.Rah2 g5 25.Qh5!+– Rb7 A) 25...Be6 26.Ke2 Rb7 transposes; B) 25...Ne5 26.Ke2 Nxc4 27.fxg5 Rxb3 is the start of a long forcing line that calls for exact play: (27...Nxe3 28.Rxh4 Rb7 29.Kxe3 Bf5 30.g6+– threatens 31.Qxh7!) 28.Rxh4 Rb2+ 29.Ke1 Rb1+ 30.Nd1 Bf5 31.g6 Rb7 32.Rf4! Be6 (32...Bxg6?! 33.Rxf8+ Qxf8 34.Qxg6 Rg7 35.Qxe4 Ne5 36.N1e3+–) 33.Rxf8+ Qxf8 34.Qxh7+ Rxh7 35.Rxh7+ Kg8 36.Ne7+ Qxe7 37.Rxe7 Bf5 All this was played in Zemlyanov-Gilbert, email 2013, where Black quickly constructed a fortress, but we can avoid it if we keep the knights on the board: 38.Rc7!N 38...Ne5 (38...d5 39.Kf2 Bxg6 40.Ne3 Nxe3 41.Kxe3 a4 42.Rc5 Bf7 43.Ra5+– is an exception, because Black’s pawns are fixed on the same colour complex as the bishop) 39.g7 Be6 40.Ne3 a4 41.Re7 Nd3+ 42.Kd2 Nc5 43.c4 a3 44.Kc2 Kh7 45.Kb1 Bg8 46.Ka2 Kg6 47.Rc7 Ne6 48.Rc8 Kxg7 49.Kxa3+– Of course, this is not necessary to memorise, but I wanted to prove that Black is technically lost after White’s gambit. 26.Ke2 Be6 27.Qh6 Bg8 Or 27...Bxd5 28.Nxd5 Rff7 29.Qe6!. 28.Rg2 Rbf7? 28...Ne5 is the engine’s first line, but then it’s a matter of technique to convert White’s extra piece after 29.fxe5 dxe5 30.Rf1+–. 28...Bxd5 29.Nxd5 Ne7 30.Rxg5 Nxd5 31.Rxd5 Bf6 32.Rdh5 Qe7 33.Qg6 Qg7 34.Qxe4 Re7 35.Rxh7+ Qxh7 36.Rxh7+ Rxh7 37.Qe3! Rc8 38.Qg3± gives an enduring initiative with the opposite-coloured bishops, and should be winning with perfect play. 29.Rxh4! gxh4 30.Nf5 h3 31.Nh4! Qxh4 32.Rxg8+ Rxg8 33.Qxh4 Black is down material for nothing (1-0, 46). 5.19 Surya Shekhar Ganguly 2654 Alexei Shirov 2682 Edmonton 2016 (9) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 Bg5 12.Nc2 Rb8 13.a4 bxa4 14.Ncb4 Nxb4 15.cxb4 0-0 16.Rxa4 a5 17.h4 Bh6 18.b5 As Ganguly already detailed his thoughts during the game, I will present a more theoretical analysis. 18...Bd7 18...Kh8 19.Be2 and now: A) 19...Bd7 20.Nc3 Rc8 21.Bc4 f5 22.exf5 Bxf5 23.0-0 Rc5!?N (23...Qxh4 24.Be6 Bf4 25.Rxf4 Qxf4 26.Bxc8 Bxc8 27.Qxd6 Bb7 28.Ne2 (28.Nd5 Bxd5 29.Qxd5 Qd4 30.Qxd4 exd4=) 28...Qf7 29.Ng3² was ultimately the better side of a draw in Domancich-Hensel, email 2013) 24.Bb3 e4 25.Bd5 (25.Nxe4 Bxe4 26.Rxe4 Rxb5=) 25...e3 26.fxe3 Bxe3+ 27.Kh2 g6 28.g3 Bh6 29.h5 Bg7 30.hxg6 Qg5! 31.Rh4 Qxg6 32.b6² Black is close to a draw but still needs to find several accurate moves; B) 19...Be6 20.b3 Rc8 21.Rc4 f5 22.exf5 Bxf5 (Farkas-Fleetwood, email 2009) 23.Bg4!N 23...Rxc4 24.bxc4 Be4 25.0-0 Qxh4 26.b6 Bc1!? (it’s quite incredible that Black has time to afford the ...Bc1-a3-c6 manoeuvre, but it does fit the principle of improving the worst-placed piece! 26...Bxd5 27.cxd5 Rb8 28.Qf3 g6 29.Rb1 Bd2 30.b7 Kg7 31.Rb5!² also calls for prolonged accuracy for Black to hold the draw) 27.b7 Ba3 28.Bc8 Bc5 29.Qd2 Bxd5 30.cxd5 Ba7 31.Bh3 Qe7! (31...a4 32.Qa5 Qd4 33.Qc7²) 32.Rb1 The position should be a draw, but the advanced b7-pawn gives White good practical chances. 19.Nc3 d5 20.exd5 e4?! This move is a bit committal, as we’ll see. 20...Kh8 21.Be2 f5, as played in Anand-Grischuk, Stavanger 2015, seems the way for Black to equalise, though he must find one quite amazing move: 22.0-0! (22.g3 f4 23.g4 f3 24.Bxf3 Bc1! 25.Qxc1 Rxf3 26.Qd1 Qf6 is completely fine for Black; 22.d6 Rf6) 22...e4 23.g3 f4 24.Rxe4 Bh3 25.Re1 fxg3 26.fxg3 Qb6+ 27.Kh2 (27.Kh1 Qf2 28.Rg1 Be3=) 27...Bf5 28.Kg2 (28.Qd4!? Bxe4 29.Qxb6 Rxb6 30.Nxe4 Re8 31.Bc4 g6 32.Re2 looks drawish) 28...Bxe4+ 29.Nxe4 Rbe8 30.Bc4 and now the amazing shot: 30...Bf4!!= Capturing the bishop exposes White’s king too much, so Black reroutes the piece to d6 and is fine. 21.Be2! f5 21...e3 22.f4! g6 23.h5 Bg7 24.h6 Bh8 25.0-0² 22.d6 Kh8 22...Qf6 23.g3 23.g3 f4 This break is less effective before White has castled, but 23...Rf6 24.Rd4 Qf8 25.Bc4 keeps Black pinned down. 24.Rxe4 Bf5 25.Re5 25.0-0! Bxe4 26.Nxe4± 25...Qf6 26.Qd5 fxg3 27.fxg3 Qg6? The decisive mistake, but even the strongest 27...g6 28.0-0 Bg7 29.Re7 Rbd8 30.Ne4 Qxe7 31.dxe7 Rxd5 32.exf8=Q+ Bxf8 33.g4 Re5 34.Nc3 Bc5+ 35.Kg2 Be6 36.Rd1 gives White healthy winning chances. 28.g4!+– Bc8 28...Bxg4 29.Rg1 29.Ne4 Bb7 30.h5 Qxe4 31.Qxe4 Bxe4 32.Rxe4 Rfd8 33.Rd4 Bc1 34.d7!? Playing for the initiative is good enough to win, as is 34.Bd3 Bxb2 35.Rd5 a4 36.Kd2 Bf6 37.Kc2+–. 34...Bxb2 35.Rd5 Rb7 36.0-0 g6 Better was 36...Ba3. 37.h6! Ba3 38.Rf7 a4 39.Re5 Rbb8 40.Bc4 Bf8 41.Kg2 a3 42.Ba2 Bd6 43.Re6 Bf8 44.b6 1-0 5.20 Viswanathan Anand 2792 Loek van Wely 2647 Wijk aan Zee 2006 (9) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 Bg5 12.Nc2 Rb8 13.a4 bxa4 14.Ncb4 Bd7 15.Bxa6 Nxb4 16.cxb4 0-0 17.0-0 Bc6 18.Rxa4 Bxa4 19.Qxa4 Qe8 20.Qxe8 Rfxe8 21.b5 21.g3! is more flexible, waiting for ...Bd2 before playing b4-b5: 21...Rf8 22.Ra1 f5 23.exf5 Rxf5 24.Bc4 Kh8 25.h4 Bd2 26.b5² 21...f5 21...Rf8! 22.b6 f5 23.Re1 fxe4 24.Rxe4 Kf7² and ...Ke6 proved sufficient to avoid defeat in Cavajda-Rydholm, email 2007. 22.b6 22.exf5 Rf8 23.g4!? 22...fxe4 23.h4!? Bd2? After 23...Bxh4! 24.Rc1 Rf8 25.g3 Bg5 26.Rc6 Kf7! 27.Rc7+ Kg6 28.b7 Rf7 29.Rxf7 Kxf7 30.Nb4 Bd8= Black looks to have a fortress with ...Bc7. 24.b7± Kf7 24...Kf8 25.Rd1 Bh6 was better. 25.Rd1 Bh6 26.Nb4! Ke7 27.Nd5+ 27.Kf1! 27...Kf7 28.g4 Bf4 29.Re1 29.Nb4!? 29...g5 30.Re2 Red8? 30...gxh4! 31.Rc2 h3² is messy, but the game continuation leads to a prosaic finish. 31.Nb4!+– d5 31...Rd7 32.Nc6 Rbxb7 33.Bxb7 wins a piece because of Nd8. 32.Nc6 Rg8 33.Nxb8 Rxb8 34.h5! Ke7 34...d4 35.Rc2! 35.Kf1 d4 36.Rc2 e3 37.fxe3 dxe3 38.Rc7+ Kf6 39.Rxh7 e4 40.Bc4 Rd8 41.Rf7+ Ke5 42.Rd7 1-0 5.21 Dmitrijus Chocenka 2458 Albert Hebels 2485 ICCF email 2008 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 Bg5 12.Nc2 Rb8 13.a4 bxa4 14.Ncb4 Bd7 15.Bxa6 Nxb4 16.cxb4 0-0 17.0-0 Bc6 18.Rxa4 Bxa4 19.Qxa4 Kh8 20.b5 Qd7 21.Qc4 f5 22.exf5 Qxf5 23.b6 e4 24.b7² Black is effectively playing without the b8-rook, and the dark-squared bishop is largely a ghost. 24...Bf4 24...Qe5 25.g3 Bd2 26.Nb6 d5 27.Qxd5 Qxd5 28.Nxd5 also gives White something to work with. 25.g3 Be5 26.Ne7 Qf3 26...Qf7 27.Qxf7 Rxf7 transposes to the game. 27.Qd5! Qf7 27...Bxb2 28.Nc6 Rbe8 29.Bc4! is clearly better for White. 28.Qxf7 Rxf7 29.Nc6 Rfxb7 30.Bxb7 Rxb7 31.b4! Bc3 32.Rc1 Bf6 33.Rd1 White’s outside passed pawn and better minor piece give him excellent winning chances, and he successfully converted in the game (1-0, 56). Chapter 6 Sidelines after 2...e6 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 In this chapter we will consider Black’s rare replies within the 2...e6 complex of the Open Sicilian, where Black does not try to stop us playing the e4-e5 break, or otherwise exerts early pressure down the a7-g1 diagonal. 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 The main moves 4...Nc6 and 4...a6 will be treated in the subsequent chapters. Unusual fourth moves A) 4...Bc5 was the recent subject of a book by Giddins, but White has several routes to an edge: A1) The gambit 5.Be3 Qb6 6.Na3! was the old recommendation. It’s also worth learning, as the same position can arise from 4...Qb6 5.Be3 Bc5 6.Na3: A11) If 6...Qxb2? 7.Nab5 is already winning, as 8.Nc7+ is threatened and the queen is running short of squares; A12) 6...Bxa3? 7.bxa3 Qa5+ 8.Bd2 Qxa3 is another unsound pawn grab, as the dark squares are too weak without the bishop: 9.Nb5 Qc5 10.Be3 Qc6 11.Qd6! and material losses are inevitable; A13) 6...Qa5+ 7.Bd2 Qd8 might be the best line, but that would indicate a failure of Black’s opening strategy: 8.Ndb5! d5 (8...a6 9.Be3! with Nd6 to follow is an important intermezzo) 9.Bf4 Na6 10.exd5 exd5 11.c3 Nf6 (Istratescu-Haugli, Oslo 2013) 12.Be2! 0-0 13.0-0 White has a small but stable advantage, as Black’s a6-knight is slightly awkward in this IQP structure. Negi gives more analysis to prove the point, but for our purposes this should be sufficient; A14) 6...d5 at least stops Nc4, but the resulting IQP will be vulnerable: 7.Bb5+ Bd7 8.exd5 exd5 9.0-0 Ne7 Black needs to block a check on the e-file, but White keeps an advantage with consolidating moves: 10.c3 Bxa3!? (Negi considers some other moves, showing b2-b4 to be a good way to keep the pressure up in reply) 11.Bxd7+ Nxd7 12.bxa3 0-0 13.Nf5 Qe6 14.Nxe7+ Qxe7 15.Qxd5 (Evans-Deschamp, email 2003) 15...b6 16.a4² It’s not an ideal pawn structure, but White holds an extra pawn and the superior minor piece. A2) 5.Nb5!? An almost unknown move, but it’s sensible to target the weak d6-square. 5...Qb6 (other moves give White time for a strong Bf4, e.g. 5...d5N 6.Bf4 Na6 looks ugly and can be punished with rapid queenside development: 7.N1c3 Nf6 8.Qf3 Qb6 9.0-0-0 0-0 10.e5 Nd7 11.Na4 Qd8 12.Nxc5 Naxc5 13.Qe3± with Nd6 likely to follow) 6.Be3! (it transpires that Black is unable to safely accept our sacrifice, while Nd6 will hurt in many lines) 6...Bxe3 7.fxe3 and now: A21) 7...Qxe3+ 8.Be2 Na6 9.N1c3 has scored 100% for White, who will play Nd6-c4 and e4-e5 for a massive initiative, such as with 9...Nh6 10.Nd6+ Ke7 11.Nc4 Qc5 12.e5!+–, as in Rattinger-Steinbrück, email 2007, among other white wins; A22) 7...d5 8.exd5 a6 is probably best, but White can take a stable endgame advantage with 9.Qd4! Qxd4 10.Nxd4 exd5 11.Nc3 Nf6 12.0-00ƒ (Fischer-Langheld, email 2012) when h2-h3/g2-g4/Bg2 will tie Black down to the d5 target; A23) 7...Nc6 gives time for the consolidating 8.Qd2! before invading d6: 8...Nf6 9.Nd6+ Kf8 10.Nc3 Now, 10...Qxb2 11.Rb1 Qa3 12.Be2! a6 13.0-0 b5 14.Rb3 Qa5 15.e5 Nxe5 16.Qd4 Nc6 17.Qh4 gives White a decisive attack. On the other hand, the positional 10...Ng4 11.Nc4 Qc5 12.h3 (Zoubkov-Keller, email 2012) 12...Nge5 13.Nd6 f6 14.0-0-0 is also considerably in White’s favour, as Black struggles to develop his queenside without shedding material; A24) 7...Nf6!? is the trickiest move, playing for a counterattack: 8.Nd6+ Kf8 (this piece sacrifice was only played once, but at least it forces a few accurate moves from White. 8...Ke7 9.Nc4 Qc5 10.e5 Ne8 11.Nc3 turns out tactically in White’s favour in the following forcing line: 11...b5 12.Ne4 Qd5 13.Qxd5! exd5 14.Ncd6 dxe4 15.Nxc8+ Ke6 16.Bxb5 Nc6 17.Nd6 Nxd6 18.exd6 Kxd6 19.0-0-0+ Kc7 20.Rhf1 with a clear advantage, as Black’s central pawns are weak in the endgame) 9.Nxc8 Qxe3+ 10.Be2 Nxe4 11.Qd3! (obviously, we should trade when up a piece or more) 11...Qc1+ 12.Bd1 Nc6 13.Qa3+ Ke8 14.Nb6 Rb8 15.Nc4 and the knight is safe, so Black is simply close to lost; B) 4...Qb6 5.Be3! was a gambit suggested in the previous edition, and it’s even better than De la Villa had thought: 5...Qxb2 (5...Bc5 6.Na3 transposes to Line A1) 6.Nd2 Don’t be afraid of being a pawn down – White’s lead in development will only increase after moves like Bd3, 0-0 and Nc4/Rb1, while Black must play very precisely to avert a rapid defeat: B1) 6...Nc6? 7.Rb1! and 8.Nb5 is already winning for White: 7...Qxa2 (or 7...Qc3 8.Nb5 Qa5 9.c3 when Nc4 and Bf4 will finish Black on the dark squares) 8.Nb5 Qa5 9.Ra1 Qd8 10.Nc4 d5 11.exd5 exd5 12.Nb6 Rb8 13.Nxd5 White has a massive lead in development in an open position, which is already sufficient for the win; B2) 6...Qb6 7.Nb5+– resembles other variations we’ve seen; B3) 6...a6 7.Bd3 (7.c3!? is Negi’s recommendation, and probably just as good) 7...Qc3 (7...Nc6 can be ignored with 8.0-0! Nxd4 9.Nc4 Qc3 10.Bd2 Nf3+ 11.Qxf3 Qd4 12.Be3 Qc3 13.e5, as noted in the previous edition – but Black is dead lost) 8.0-0 Qc7 (8...Nc6 9.Nc4 b5 can be met forcingly with 10.Ne2 Qf6 11.Nb6 Rb8 12.Nxc8 Rxc8 13.a4ƒ when we will regain the pawn with interest) Initially the engines believe Black can defend, but if we play natural attacking moves, it’s all bad news for him. 9.e5! (9.f4?! Nf6! is not so clear) 9...d6 (9...Qxe5 10.Nc4 Qc7 tactically fails to 11.Nxe6 dxe6 12.Nb6±, picking up the exchange; 9...b5? 10.a4 b4 11.Nc4+– is even more unpleasant – Qg4 will prohibit Black’s kingside development) 10.f4! (when playing a gambit, we should not be afraid to throw more wood into the fire to keep the initiative burning) 10...dxe5 (10...Nd7? is a human move, but 11.Nxe6!N 11...fxe6 12.Qh5+ Kd8 13.Ne4 d5 14.Ng5 already forces Black to return the material with 14...Ndf6, which would crown the success of White’s dynamic play) 11.fxe5 Qxe5! (it takes guts to grab the second pawn, but everything else just loses, e.g. 11...Ne7 12.Qf3 Nd5 13.Rae1 Nxe3 14.Rxe3 Bc5 15.c3 Nc6 16.Nc4 and as Black can’t castle due to 17.Bxh7+, he is unable to nullify White’s development advantage) 12.Nc4 Qc7 13.Rb1 (Black remains under heavy pressure) 13...Bc5 (13...b5? 14.Qf3 bxc4 15.Nxe6! Bxe6 16.Qxa8 Bd6 17.Bf4! shows White’s tactical possibilities – one can sense that such possibilities will exist with such a considerable lead in development) 14.Qg4 f5 15.Bxf5!? (15.Qf3 is also possible, but it’s hard to resist a strong sacrifice!) 15...Nf6 16.Qg5 exf5 17.Nxf5 Bxf5 18.Rxf5 Be7 (Black needs to castle fast, or his king will quickly get mated in the open centre; 18...Bxe3+ 19.Qxe3+ Kd8 20.Nb6+–) 19.Nb6 0-0 20.Nxa8 Qxc2 Black has escaped into an exchange down position, but White’s initiative persists after the precise 21.Rff1! Nbd7 22.Nb6 Nxb6 23.Bxb6 Qxa2 24.Qe5!± (Borzenko-Stephan, email 2008) and with Bd4 in mind, Black still suffers from worse coordination and a clear disadvantage. White should just be careful not to trade queens, as with so few white pawns remaining, several endgames will be drawn. I doubt any opponent will play to this point in an actual game, but developing a feel for such gambit play is an important aspect of any player’s development; C) 4...Nc6 5.Nc3 Bc5?! is a junky line, easily refuted by 6.Ndb5 Qb6? (6...Nf6, transposing to the Four Knights, limits the damage) 7.Qd2! followed by 8.Na4: 7...a6 8.Na4± Carvalho-Koronowski, email 2011. 4...Nf6 5.Nc3 5...d6 transposes to the Scheveningen chapter, but here we’ll consider the alternatives, which feature more direct play. The Gaw-Paw Variation 5...Qb6 is the Gaw-Paw Variation, and rightly spurned by theory: 6.e5 Bc5 7.Ndb5! and since taking on f2 fails tactically, Black already faces major difficulties. 7...a6 (7...Nd5 8.Ne4! and c2-c4 is an easy positional domination for White, Eldridge-Jefferson, email 2011; 7...Bxf2+ 8.Ke2 Ng4 9.h3! Nxe5 10.Qd6 already wins a piece, as the reader can confirm for themselves (Akbaev-Blednov, Cherkessk Habez 2014)) 8.Qf3! Among various good moves, this is the most clinical, retaining the initiative: 8...axb5 9.exf6 gxf6 10.Bxb5N 10...Nc6 11.0-0± Black has no safe refuge for his king and normal development by White will be strong. The Pin Variation 5...Bb4?! is the Pin Variation, which relies on White showing Black’s premature attack too much respect. 6.e5! This is almost always a good follow-up to 5.Nc3, when Black hasn’t covered this square. Now: A) 6...Qc7? tactically fails to 7.exf6 Bxc3+ 8.bxc3 Qxc3+ 9.Qd2! Qxa1 10.fxg7 Rg8 11.c3 Qb1 (else Nb3/Bd3 traps the queen) 12.Bd3 Qb6 13.Qg5 and the g7-pawn is about to win a rook, meaning Black’s position is already resignable, Kazakov-Todorov, Valjevo 2000; B) 6...Ne4?! 7.Qg4! Nxc3 (at the end of the tactical sequence 7...Qa5 8.Qxg7 Bxc3+ 9.bxc3 Qxc3+ 10.Ke2 b6 11.Qxh8+ Ke7 12.Ba3+ Qxa3 13.Qxc8 Qb2 14.Ke3 Qxa1 15.Kxe4 (Negi), White is just a piece ahead) 8.Qxg7 Rf8 (discovered checks are refuted by c2-c3) 9.a3! is almost winning for White, though it requires some calculation to prove it: 9...Nb5+ (this move at least allows Black to reach a miserable endgame. 9...Nc6 10.axb4! Nxd4 11.bxc3 Nxc2+ 12.Kd1 Nxa1 13.Bg5 is crushing, with Bh6 in reply to a queen evacuation; 9...Qa5 looks tricky but allows various winning moves. The very best is 10.axb4! Qxa1 11.Nb3 Qb1 12.bxc3 Qxc2 13.Bh6 Qxc3+ 14.Nd2 Qxb4 15.Be2 Nc6 16.0-0 when Black is unable to develop in time to stop crushing threats like Ne4-d6, as in Epure-Darvas, email 2011) 10.axb4 Nxd4 11.Bg5! (we could play 11.Bh6 first, but I want to deprive Black of a ...Qe7 defence) 11...Qb6 12.Bh6 (12.Bd3! might be even stronger, but is more demanding) 12...Qxb4+ 13.c3 Nf5 14.cxb4 Nxg7 15.Bxg7 Rg8 16.Bf6 (Black has a severe problem developing his queenside) 16...Nc6 17.Bd3 h6 18.b5 Nb4 19.Bh7 Rg4 20.Ra3! Kotronias/Semkov give a clear edge for White, as taking on g2 merely opens the g-file for a mating attack. It would probably be feasible to prove a forced win for White with a detailed analysis, but it’s not necessary for such an obviously weak line; C) 6...Nd5 7.Qg4! My chess philosophy is that, if we can safely ignore the opponent’s threat, it’s probably a good idea. C1) 7...Nxc3 transposes to 6...Ne4; C2) 7...g6... ... weakens the dark squares even more, a factor we can directly exploit with 8.Ndb5! Nc6 9.Qg3 0-0 10.a3, forcing the pace, as in Allerberger-Camacho, email 2011: 10...Be7 (10...Bxc3+ 11.bxc3!?± gives Black’s position a striking resemblance to swiss cheese) 11.Bh6! Bh4 12.Qh3 Nxc3 13.Nxc3 Black has to sacrifice the exchange to avoid facing a decisive initiative, but it’s hard to complain about a material advantage: 13...Nxe5 14.Bxf8 Kxf8 15.0-0-0 Kg8 16.f4 Nc6 17.g4 and we still have some kingside initiative to go with the material – if 17...Bf6 18.Qg3! and h4-h5 is coming; C3) 7...Kf8 is the engine’s first line, but it’s hard to play with your king in the centre like this, and simple chess gives White a healthy initiative: 8.Bd2 h5 (8...Bxc3 9.bxc3 Qc7 10.Qg3± keeps our pawns safe, Vujakovic-Smuk, Sibenik 2008; 8...Nxc3? 9.Nxe6+! is a key trick; 8...d6 9.exd6 Qxd6 10.0-0-0± is a better version of the 8...h5 variation for White: 10...Bxc3 11.Bxc3 Nxc3 12.Nxe6+! Bxe6 13.Rxd6 Bxg4 14.Rd8+ Ke7 15.Rxh8 is the key tactical point, when Black struggles to develop the rook and b8-knight) 9.Qe4! (Stankovic-Zivkovic, Serbia tt 2011) The e5-pawn is a typical target, so it makes sense to centralise our queen and force Black’s hand. 9...d6! 10.Rd1 Bxc3 11.bxc3 dxe5 12.Qxe5 Qe7 13.Bd3 Nd7 14.Qe2² This seems the best outcome for Black after 7.Qg4, but White has an obvious initiative with the bishop pair and Black’s exposed king. Furthermore, it feels far easier to play White, who can proceed with 0-0, c2-c4 and f4-f5 almost by hand; C4) 7...0-0 is a thematic exchange sacrifice for the variation, but we don’t have to accept the gift immediately: 8.Bh6 g6 9.a3! (Negi recommends this line as the key point behind 7.Qg4, as all Black’s attempts to keep the tension run into tactical problems) 9...Qa5 (9...Bxc3+ 10.bxc3 Nxc3 11.Bxf8 Qxf8 12.Nb3 doesn’t grant Black real compensation for the material deficit; 9...Ba5 10.Bxf8 Kxf8 11.Nde2! is an improved version of 9.Bxf8, as White has options to unpin with b2-b4 in the future: 11...Nxc3 12.Nxc3 Bxc3+ 13.bxc3 Nc6 14.Qg3± Black can try to pressure the e5-pawn, but ultimately, he lacks the development to justify the exchange sac) 10.axb4! Qxa1+ 11.Nd1 Nc6 12.Bb5! (White already sacked an exchange, so a pawn is nothing at this point) 12...Ndxb4 13.0-0 Qa5 14.Ne3 Negi stops his analysis here, as Black is unable to bring his pieces to the defence of his king. For clarification, let’s see why Black can’t win a piece: 14...Nxd4 (14...Nd5 is the engine’s line, but then we can easily transform our initiative with 15.c4! Nxd4 16.Nxd5 exd5 17.Qxd4 Qb6 18.Qh4!+–) 15.Qxd4 Qxb5 16.Qh4 f6 17.Bxf8 Kxf8 18.exf6 h5 19.Qf4 and Black must give up material to avoid getting mated on the dark squares. These lines aren’t hard to reconstruct once you play through them – the consistent motif is to always play the move you want to make work, relying on White’s lead in development. The Four Knights Sicilian 5...Nc6!? This preparation for ...Bb4 and ...d7-d5 is a common variation in junior tournaments and often misplayed by White at the club level, so we should commit the next few moves to memory. 6.Ndb5 This is the easiest solution for White, though the possible transposition to the Sveshnikov after 6...d6 would be unpleasant for Rossolimo exponents. 6...Bb4 The most active move, forcing White’s hand. A) 6...d6 7.Bf4 e5 8.Bg5 is the aforementioned transposition to the Sveshnikov, but with one more move played (...e6e5 and Bf4-g5); B) 6...Bc5!? is the pesky Cobra, which calls for pointed play from White: 7.Nd6+! (Negi’s recommendation, which I agree with, as the old suggestion 7.Bf4 0-0 8.Bc7 Qe7 9.Bd6 Bxd6 10.Qxd6 Ne8 11.Qxe7 Nxe7 12.0-0-0 f5 13.Nd6 Nxd6 14.Rxd6 fxe4 15.Nxe4, while being a safe endgame, is also rather hard to win if Black plays the normal ...Nf5/...d7-d5 (as essayed many times by Chernov), or even the patient 15...b6!?²) 7...Ke7 8.Bf4 e5 9.Nf5+ Kf8 10.Bg5 d6 (10...Bb4 11.Ne3! Qa5 12.Nc4 Bxc3+ 13.bxc3 Qxc3+ 14.Bd2 Qd4 15.f3 Kg8 16.c3 Qc5 17.Bc1 and Ba3 is noted by Negi to be very much in White’s favour. Black is unable to develop his queenside, Huschenbeth-Chernov, Neustadt an der Weinstrasse 2017) I checked several options and found Black’s position is not so bad as his strong bishop on c5 partially compensates the uncastled king, which may easily correct its position with a later ...h7-h6/...g7-g6/...Kg7. Even so, White scores superbly in practice and possesses a real edge to boot: B1) 11.Bxf6 Qxf6 12.Nd5 Qd8 13.Nfe3 Be6 14.Qd2 g6 15.0-0-0 Kg7= represents the type of position Black is seeking; B2) 11.Bc4 Be6 12.Bb3 h6 13.Bxf6 Qxf6 14.0-0 Bxf5 15.Nd5 Qg5 16.exf5 Qxf5 17.c3 is an ambitious try, when White has good compensation for the pawn, but probably not an objective advantage; B3) 11.Bd3 was Negi’s recommendation. Personally, I want to avoid 11...Bb4! 12.0-0 Bxc3 13.bxc3 h6 14.Bxf6 Qxf6 when White’s structure is not ideal, though White holds a slight pull with 15.Ne3²; B4) 11.Ne3!? is a simple enough plan, focusing on d5: 11...Be6 12.Qd2!? (12.Be2N and kingside castling is also fine) 12...h6 13.Bxf6 Qxf6 14.Ncd5 Qg6 15.f3 White will castle queenside, and Black’s difficulty involving the h8-rook in the fight gives White an edge, though Black’s position is not going to collapse easily. 7.a3! 7.Bf4 Nxe4 8.Qf3 is a sharp line that the engines initially like for White, but I couldn’t find a white edge in the following forcing variation: 8...d5 9.Nc7+ Kf8 10.Nxa8 e5 11.Bd2 Nd4 12.Qd1 Qh4 13.g3 Qf6 14.Nxe4 Nf3+ 15.Qxf3 Qxf3 16.Bxb4+ Kg8 17.Nd6 Qxh1 18.0-0-0 Be6 19.Nc7 Qxh2 20.Nxd5 (Zylka-Szustakowski, Karpacz 2015) 20...Bxd5!N 21.Rxd5 Qxf2 22.Rxe5 Qxf1+ 23.Re1 Qxe1+ 24.Bxe1 h5!= and Black is just in time to create sufficient counterplay with ...g7-g5 and ...h5-h4. As fascinating as this variation is, 7.a3 is simply a better move. 7...Bxc3+ 8.Nxc3 8...d5 Black needs this break before the d-pawn is blockaded. 8...0-0 9.Qd6! Ne8 10.Qg3 d5 11.Bd3 is a considerably worse version for Black, as closing the position with 11...d4 12.Ne2 e5 fails to neutralise White’s initiative after the poised 13.f4! f6 14.0-0ƒ with a nice King’s Indian style attack in the making, Purdy-Charmatz, Sydney 1944. 9.exd5 9.Bd3 dxe4 10.Nxe4 Nxe4 11.Bxe4 Qxd1+ 12.Kxd1 Bd7 13.f3!? (prophylaxis against ...f7-f5, as effectively demonstrated in Jacobsen-Kuhne, email 2008) 13...0-0 14.Be3 looks like a small endgame edge, in case you aren’t happy with the fact that Black can gradually equalise in our main line. 9...exd5 The simplifying 9...Nxd5 has been tried a few times by Safarli, Lintchevski and Popov, but White’s play feels easier here than in the main line: 10.Bd2!? (I’d rather keep the pieces on the board for now, to avoid endings the opponent may have worked out how to defend successfully in his home analysis) 10...0-0 If Black initiates exchanges, we activate our pieces with the recaptures. 11.Qh5! e5 12.0-0-0 (White has easy play with the bishop pair and attacking chances on the kingside) 12...Be6 13.Bh6!? (White has several good alternatives, but this one is rather beautiful! 13.Nxd5 Qxd5 14.Bh6 Qe4 15.Bd3 Qg4 16.Qg5 Rac8 17.f3 Qxg5+ 18.Bxg5 is another marginally better endgame, while 13.Bb5!?N will be suitable for those wanting to keep the queens on) 13...gxh6 14.Nxd5 (Berg-Westerberg, Umea 2015) 14...Qg5+ 15.Qxg5+ hxg5 16.Nc7 Bg4 17.f3 Rac8 18.fxg4 Rxc7 19.Bd3 Rd8 20.Be4 White has a risk-free endgame advantage, and the bishop vs. knight and structural imbalances make it hard for Black to construct a fortress. 10.Bd3 0-0 Trying to attack White early is premature: A) 10...Bg4?! 11.f3 Be6 12.Bg5 h6 13.Bh4 0-0 14.Qd2!?± and 0-0-0 shows an extra option offered by Black’s committal move order, Paris-Grkinic, corr 1999; B) 10...Qe7+?! 11.Qe2 Qxe2+ 12.Nxe2 0-0 13.Bf4ƒ and 0-0-0 is one of the best versions of the typical endgame for White, Bittencourt-Rocha, Lisbonne 2006. 11.0-0 In my experience, it’s not that easy to handle Black’s piece activity and coordinate the bishop pair in practice, so I’ve deliberately included some rare moves by Black: 11...d4 A) 11...h6 12.Bf4 Re8 (12...d4 13.Nb5!) 13.Qd2 Ne5N 14.Rfe1 Nxd3 15.Qxd3² is a useful demonstration that exchanging White’s bishop pair is not an automatic panacea, as White’s remaining bishop is clearly better than its counterpart; B) 11...Bg4 12.f3 Bh5 is largely a bluff and should be called by White: 13.Bg5! Qb6+ 14.Kh1 Ne4 (14...Qxb2? 15.Bxf6 gxf6 16.Qd2 is obviously a disaster for Black, who can’t protect his weak king; 14...Ne7 15.Re1 also leaves Black struggling to avert a crisis) 15.Nxe4 dxe4 16.Bxe4 Qxb2 17.Qb1 Qxb1 18.Rfxb1 (Ehlvest-Romero Holmes, Logrono 1991) Here a novelty for Black is to sacrifice a pawn to trade off White’s mighty bishop pair: 18...Bg6!? 19.Bxg6 hxg6 20.Rxb7 Na5, but Black is by no means close to a draw after 21.Rd7!? Rfc8 22.Be3 a6 23.Ra2 – White’s active rook and bishop give scope to grind out the win. 12.Ne2 White’s two main plans involve pressuring the d4-pawn – with either Bg5/f2-f3/Bh4-f2 or b2-b4/ Bb2/b4-b5, but the correct choice depends on Black’s next move. Unusual 12th moves A) 12...Nd5?! 13.Nf4 induces concessions, as Bxh7+/Qh5 is threatened; B) 12...Be6 13.b4! a6 14.Bb2ƒ forces contortions to avoid the loss of a pawn to the Nxd4 tactic, Bindrich-Auschkalnis, Fürth 2002; C) 12...Ne5? 13.Nxd4 Bg4 14.Qd2 is an extra pawn for White; D) 12...a6 anticipates b2-b4/Bb2/b4-b5, but 13.Bg5! leaves the pawn move looking a bit wasteful, Wölfl-Secrieru, email 2011; E) 12...Qd6?! 13.Bf4 Qd5 14.Ng3 Ne5 15.Nh5 shows how White can benefit from the free Bf4 move; F) 12...Qb6 discourages Bg5, but we have the alternative 13.b4! Bg4 14.Bb2 Rad8 15.Qd2 when Black will eventually have to submit ...Bxe2 to save his d4-pawn: 15...Rfe8 16.Rfe1 a6 17.h3 Bxe2 18.Rxe2 Rxe2 19.Qxe2 White has a typical bishop pair advantage, and indeed won the two email games to reach this position; G) 12...h6 is similarly single-minded, and well met by 13.b4 Bg4 14.f3 Be6 15.Bb2 a6. Now it’s important to remember the way to threaten Nxd4 tricks: 16.Kh1! (so that a later ...Qxd4 would not come with check, giving time for Bh7 discovered checks) 16...Kh8 17.Qe1± with the idea of Qf2/Rd1 to collect the surrounded d4-pawn. See RytshagovLiiva, Tallinn rapid 1996. Major alternatives to 12...Bg4 H) 12...Re8 13.Bg5! (I now believe that this is important, as the b2-b4 plan is a little slow against aggressive development: 13.b4 Bg4 14.f3 Bh5 15.Bb2 Nd5!? 16.Qd2 Bg6!N 17.Nxd4 Ne3! is an important improvement over the previous edition, with the idea 18.Rfe1 Nxd4 19.Rxe3 Rxe3 20.Qxe3 Nxc2 21.Bxc2 Bxc2 22.Qc3 Qb6+ 23.Kh1 Qg6 and a somewhat drawish position because of the opposite-coloured bishops) 13...Bg4 (13...Re5 is surprisingly common in correspondence, but it’s simply a poor line because of 14.f4! Re8 15.Qe1! h6 16.Qh4! and Black’s position is just horrible if he doesn’t accept the piece sacrifice, but after the critical 16...hxg5 17.fxg5 Nd5 18.Qh7+ Kf8 19.g6 f6 (Jansen-Reina Guerra, email 2011) 20.Nf4! Nxf4 21.Rxf4 – Black is getting hacked to bits with Raf1 and Rxf6 in mind) 14.Re1 Qd6 (the engine wants to move ...Bxe2 or ...Bh5, but such quiet play can be met in a similar way to 14...Qd6, with advantage) 15.Qd2 Bxe2 16.Bf4! Forcing Black’s queen to an inferior square. I’ve included all the serious options, for illustrative purposes. H1) 16...Qd5 is an exposed position for the queen: 17.Bxe2 (Motylev-Zhang, China tt 2008) 17...h6 18.Bf3 Qf5 19.Bg3² and the bishops are quite harmonious side by side; H2) If 16...Qc5, 17.b4!? looks ugly, but is not so silly: 17...Qd5 18.Rxe2!? (18.Bxe2 gave two wins in correspondence chess, but the arising positions are not so different) 18...Rxe2 19.Bxe2 Re8 (19...Ne4 20.Bf3! is the key point, stopping 20...Nc3) 20.Bf3 Qe6 21.b5 Nd8 22.a4² White has the better minor pieces and Black’s queenside pawns are a bit weak; H3) 16...Qd7 17.Bxe2 Ne4 18.Qd3 It’s a bit surprising that Black scores well from here, as it’s quite easy to build up White’s position with moves like g2-g3, Bf3 and Rad1, preventing any tricks with the knight. 18...Qf5 (18...Nc5 19.Qb5 Re4 20.Qxc5 Rxf4 21.Bd3 is a pleasant transformation for White, as the f4-rook will need some time to reroute. It’s one advantage of having two bishops vs. two knights – we can transform the advantage with a minor piece trade at the right moment) 19.g3 Qd7 (Sadvakasov-Al Modiahki, Doha 2003; 19...g5? fails to the intermezzo 20.Bf3!) 20.Rad1 White is fully mobilised and should not find it hard to set Black long-term problems with continual improving moves. I) 12...Qd5 13.Nf4 Qd6 This avoids both Bg5 and b2-b4, but our active knight gives us other options, notably 14.Nh5!, which has been seen in numerous games, though White’s play is rather straightforward – Four Knights expert Safarli only scored ½/3 as Black. 14...Nxh5 (14...Qe5 is the engine’s first line, trying to prompt exchanges on his terms, but I don’t fancy Black’s chances after 15.Ng3 Re8 16.Qd2!? Qd5 17.b4 Be6 18.Bb2² (Fraser-Belmar Juaranz, email 2010), when the point of White’s weird moves is revealed – we are ready to pressure the d4-pawn with moves like Rfd1, Ne2 and a2-a4/b4-b5) 15.Qxh5 h6 16.Re1 Bd7 This continuation, with the idea of swapping down, is how the correspondence player Goncharenko proceeded to hold many draws decades ago. But modern engines are much better at continually advancing White’s position, and a continuation like 17.Qh4! Rfe8 18.Bf4 Qd5 19.f3 Bf5 20.Qh5 Be4 21.Qxd5 Bxd5 22.h4!N (following the endgame principle of fixing the opponent’s pawns) 22...f6 23.Kf2 is a risk-free endgame edge for White. Perhaps in correspondence Black would sit and hold the draw, but in an OTB game Black will be suffering for a long time as White manoeuvres on both flanks. The main line 12...Bg4 The main line, provoking a slightly loosening f2-f3, but that is definitely not the only option: A) 13.Bg5 h6 14.Bh4 Bxe2 15.Qxe2 Re8 16.Qf3 Ne5! 17.Qxb7 Nxd3 18.cxd3 Qd5 gives Black drawing compensation for the pawn, according to my analyses. I’d rather avoid positions where Black can memorise forcing computer lines to hold a draw; B) The flexible 13.Re1!? might be White’s best move, but it hasn’t been tested much: 13...Bh5!N (13...Re8 14.Bg5 transposes to 12...Re8; 13...Qb6 14.b4 Ne5 15.Bb2 Rfd8 16.Qd2 Nxd3 17.Qxd3 Bxe2 18.Rxe2 a5 19.b5 Rd5 20.a4 is a bit better for White, as the d4-pawn is exposed; 13...Bxe2 14.Rxe2 Qd6 15.Bg5 is a small but pleasant plus for White; 13...Qd5 14.h3 Bxe2 15.Rxe2 Rfe8 16.Bf4 Rad8 17.Rxe8+ Rxe8 18.Qf1 is not a big edge, but Black is under long-term pressure, and exchanging the major pieces will increase the value of White’s bishop pair) This is a hard move to explain, but it makes Bg5 a lot less effective due to ...Ne5xd3/...Bg6 ideas. 14.b3!? (14.Bg5 h6 15.Bh4 Ne5 was my initial reason for rejecting 13.Re1, as it is quite easy for Black to simplify his way to a drawish position; 14.b4 a5! is why I want to play 14.b3) 14...Re8 15.Bb2 Ne4 16.Bxe4 Rxe4 17.f3 Re6 18.Qd2 Rd6 19.Rad1 f6 Here too Black is objectively fine, but at least White can ask a few questions with 20.Nxd4 Qb6 21.b4 a5 22.c3, when with an extra pawn, only White can play for a win. 13.f3 Bh5 14.Bg5! 14.Nf4 Bg6 15.Nxg6 hxg6 16.f4 would be my recommendation for fast time controls, as White scores heavily in practice. But cold engine analysis shows that 16...Qb6!? is quite sufficient, with the idea of meeting 17.f5 with 17...Ne5, or after 17.Qf3 Rfe8= to play ...Ne7-f5. Black has drawn all four correspondence games to reach this point, so clearly an alternative is called for. 14...Bg6! This is an important finesse, not covered in the previous edition. But trading White’s bishop pair is very logical. A) 14...Re8 15.Bh4! is likely to transpose with 15...Bg6. Instead 15...Rc8 16.Qd2 Ne5 17.Rfe1 Nxd3 18.cxd3 offers a solid edge because of the weak d4-pawn; B) 14...Qd6 is the old main line, but it allows White to pressure the d4-pawn with a typical manoeuvre: 15.Bh4! Nd5 (15...Rad8 16.Ng3 Bg6 17.Ne4 Bxe4 18.fxe4 and Bxf6 is highly unpleasant; 15...Bg6 is best, transposing to 14...Bg6) 16.Bf2 Rad8?! (16...Nf4²) 17.Nxd4 Nxd4 18.Bxd4 Nf4 19.c3 Ne6 20.Be4 White retains the extra pawn with this attack. 15.Bh4! A good regrouping, but another interesting attempt is 15.Qd2 Re8 16.Rfe1! (anticipating the plan with ...Qb6 and ...Re3), making life difficult for Black, e.g. 16...Qb6 17.Bxf6 gxf6 18.Nf4 Re5 19.b4 or 16...Bxd3 17.Qxd3 h6 18.Bh4 with the idea Bf2. 15...Re8 A) 15...Qb6?! 16.Bxf6 gxf6 is now very pessimistic: 17.Ng3 Ne5 18.f4 Nxd3 19.cxd3 f5 20.Qd2 Rfe8 21.Rfe1² and the computer underestimates how difficult the Black position is, as the g6-bishop is placed appallingly; B) 15...Qd6 16.Bg3 Qd7 17.Bxg6 hxg6 18.Qd2 is given by Negi as slightly better for White. My analysis backs up the conclusion: 18...Rad8 19.Rfd1 Rfe8 20.Bf2 g5 21.Nxd4 g4 22.Qf4 gxf3 23.Qxf3 Ne5 24.Qf5² as in SchullerSchönbeck, email 2013. 16.Bxg6 hxg6 17.Bf2 Qb6 18.Qd2 Rad8 19.Rfe1 This is Negi’s main line. I must admit that White doesn’t seem to have a serious advantage, but I have been unable to find a clearly better variation for White, and at least the position is easier to play as we can play improving moves like a3-a4, b2-b3 and Nf4-d3. Black should trade the rooks when possessing an IQP, hence: 19...Re5!N 20.b3!? 20.h3 a5 21.a4 Rde8 looks fine for Black, as ...Nd5 tends to be good against passive play. 20...Qa6! 20...Rde8 21.b4 a6 22.h3 feels like a small edge, as the d4-pawn is a bit exposed. 21.Nxd4 Rxe1+ 22.Rxe1 Qxa3= White can try to grind with the bishop vs. knight, but objectively Black is fine. Summary 2...e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4: 4...Bc5 5.Be3 Qb6 6.Na3 – +0.35 4...Qb6 5.Be3 Qxb2 6.Nd2 – +0.75 4...Nf6 5.Nc3: 5...Qb6 6.e5 – +0.80 5...Bb4 6.e5 Nd5 7.Qg4 – +0.45 5...Nc6 6.Ndb5 Bb4 7.a3 Bxc3 8.Nxc3 d5 9.Bd3 – +0.20 9.exd5 Nxd5 – +0.50 9...exd5 10.Bd3 0-0 11.0-0 d4 12.Ne2: 12...Re8 – +0.45 12...Qd5 – +0.55 12...Bg4 – +0.25 6.1 Jörg Jacobsen 2173 Rainer Kuhne 2004 Germany email 2008 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Ndb5 Bb4 7.a3 Bxc3+ 8.Nxc3 d5 9.Bd3 We can’t force an advantage with 9.exd5, so adding another string to your bow makes sense, especially if you’ve studied 100 Endgames You Must Know! 9...dxe4 A) 9...d4 10.Ne2 e5 11.0-0 0-0 12.f4 (White’s undermining resembles an improved King’s Indian) 12...exf4 (12...Bg4 13.h3 Bxe2 14.Qxe2 Nd7 15.f5² sets White up perfectly for the kingside attack) 13.Bxf4 Ng4 (13...Qb6 14.Qe1 Re8 15.Qh4!² Simmelink-Hassim, email 2006) 14.Qe1 Be6 15.Qg3N 15...f6 16.b4 a6 17.a4! Nce5 (17...Nxb4? 18.Rab1±) 18.h3 Ne3 19.Rf2! Qd6 20.Rb1² Black can’t avoid Nxd4, pilfering a pawn; B) 9...0-0 10.0-0 h6 11.exd5 exd5 transposes to 9.exd5. 10.Nxe4 Nxe4 11.Bxe4 Qxd1+ 12.Kxd1 Bd7 A) A surprisingly common mistake is 12...f5? 13.Bxc6+! bxc6 14.Re1±; B) 12...e5!? is probably the way for Black to equalise: 13.Be3 (13.Re1 f6 14.c3 Be6 15.Kc2 0-0-0= and ...Bd5 will trade off White’s bishop pair) 13...Be6 14.Bxc6+ bxc6 15.Kc1 (15.a4 0-0-0+ 16.Ke2 Kb7 17.f3 Rhe8 looks completely equal to me) 15...a6 16.Rd1 Rd8 17.Rxd8+ Kxd8 18.Kd2 and the endgame should be a straightforward draw, though I’d rather be White; C) 12...0-0 is slightly inaccurate as the king belongs in the centre: 13.Be3 e5 14.Ke2 Be6 15.Rad1² 13.f3 f5?! In case of 13...0-0-0, instead of 14.Be3 f5 15.Bd3 e5 16.Kc1 f4!N 17.Bf2 g6= White can play 14.Ke1! when both 14...f5 15.Bd3 e5 16.Kf2 and 14...f6 15.Be3 e5 16.Bxc6 Bxc6 17.Bxa7 offer White a small advantage. 14.Bd3 Kf7 15.Be3 Now it is not so easy for Black to neutralise White’s bishop pair. 15...h6 Better was 15...e5. 16.c4?! The right idea, but only when the majority is properly supported. 16.Re1 was preferable. 16...Ne5 17.Be2 Ba4+ 18.Kd2 Rhd8+? The wily 18...Bb3! blockades the majority, in light of 19.Kc3 Bxc4 20.Bxc4 Rhc8 21.b3 b5=. 19.Kc3± Now the advance of White’s majority plays itself. 19...b6 20.b3 Bc6 21.a4 Ke7 22.a5 Nd7 23.b4 Rab8 24.h4 e5 25.Rhd1 f4 26.Bf2 g5 27.axb6 axb6 28.Ra7 Ke6 29.b5 Ba8 30.c5 Bd5 31.Rxd5 Nf6 32.Rxd8 Rxd8 33.Bc4+ Nd5+ 34.Kb3 bxc5 35.Ra6+ Kf5 36.Bd3+ e4 37.fxe4+ Ke5 38.exd5 Rxd5 39.Kc4 1-0 6.2 Emanuel Berg 2573 Jonathan Westerberg 2478 Umea 2015 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e6 6.Ndb5 Bb4 7.a3 Bxc3+ 8.Nxc3 d5 9.exd5 Nxd5 10.Bd2 0-0 11.Qh5 e5 12.0-0-0 Be6 13.Bh6 gxh6 14.Nxd5 Bxd5? Better was 14...Qg5+. If 14...Rc8 15.Nf4 Nd4 16.Nxe6 fxe6 17.Kb1 Rxf2 18.Bd3 Qg5 19.Qh3±. 15.Bc4 Qg5+ 16.Qxg5+ hxg5 17.Bxd5± Black can’t enter this bishop vs. knight battle without some compensating factor. 17...Rac8 18.h4! Nd4?! 18...g4 19.Rhe1 Rfe8 20.Be4 Rc7 21.Rd6± 19.Kb1 19.c3! shuts Black out, but with a long-term advantage, all roads lead to Rome. 19...Rc5 20.c4 b5 21.Rhe1 bxc4 22.Rxe5 Ne6 23.Rf5 Rc7 23...c3 24.Rc1! cxb2 25.Rxc5 Nxc5 26.hxg5+– 24.Bxe6 fxe6 25.Rxf8+ Kxf8 26.hxg5+– Black is a pawn down and owns an archipelago of pawns. White won the game on move 57. 6.3 Jorge Bittencourt 2398 Jorge Wilson Rocha 2247 Lisbonne 2006 (6) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e6 6.Ndb5 Bb4 7.a3 Bxc3+ 8.Nxc3 d5 9.exd5 exd5 10.Bd3 Qe7+ 11.Qe2 Qxe2+ 12.Nxe2 0-0 13.Bf4ƒ Ne4 After 13...Re8 14.0-0-0 Ne4 15.Bxe4 dxe4 16.h3± Black’s c8-bishop is too constricted. 14.b4?! 14.f3 Nc5 15.Bb5± is better, preserving the option of 0-0-0. 14...Re8 15.0-0 Bd7 Less problematic was 15...Ne5 16.Rfe1 Nxd3 17.cxd3 Nf6 18.Nd4². 16.f3 Nf6 17.Rfe1ƒ Ne5 18.Bxe5 18.Nd4!? was probably rejected because of the exchange of rooks arising from 18...Nxd3 19.cxd3 Rxe1+ 20.Rxe1 Re8 21.Rc1 Rc8 22.Rxc8+ Bxc8 23.Kf2±, but opposite-coloured bishops endgames become much less drawish with even one set of knights added. 18...Rxe5 19.Nd4² Rxe1+ 20.Rxe1 Rc8 We should trade rooks when possessing an isolated pawn on a half-open file, hence 20...Re8!? was advisable. 21.Ra1 21.a4 simplifies too many pawns after 21...Bxa4 22.b5 a6 23.bxa6 bxa6 24.Bxa6 Rb8²; 21.Kf2 was preferable. 21...g6 21...Ne8 22.Kf2 Kf8 23.a4 Ke7 24.Ke3 Be6?! 24...Ne8!² 25.Nb5 25.g4! 25...a6 26.Nd4 Nd7! 27.a5 Ne5 28.Kd2 Nc4+?! 28...Kd6 29.Bxc4 Rxc4 30.c3 White outplays his opponent with the superior minor piece from here, though this is more suited to an endgame treatise. 30...Kd6 31.Re1 Bd7 32.g4 f6?! 32...h6 33.h4 Rc8 34.g5 Rf8 35.Rh1 h5?! 35...Rf7² 36.Rg1 Be8 37.Ke3 fxg5 38.Rxg5 Rf6 39.f4 Bd7 40.Re5?! 40.f5! Bxf5 41.Nxf5+ gxf5 42.Kf4 Re6 43.Rxh5 Re4+ 44.Kxf5 Re5+ 45.Kg6 Re6+ 46.Kf7 Re7+ 47.Kf8± 40...Rf7 41.Nb3 Rf6? Better was 41...Kc6. 42.Nc5 Bc6 43.Rg5± Kc7?! 43...Ke7 44.Rg1 44.f5!+– 44...Bb5 45.Rg3 b6 46.axb6+ Kxb6 47.Rg5 Kc6 48.Nb3! Kd6 49.Nd4 Bd7 50.Rg1 Kc7 51.Ra1 Kb6 52.Ra5 Bb5 53.Ra1 Bd7 54.Rg1 Kc7 55.Rg5 Kd6 56.Nf3! Be8 57.Ne5 Kc7 58.Rg1 Kb6? 58...Kb7± 59.Rd1 Bc6 60.Rxd5!+– Rxf4 60...Bxd5 61.Nd7+ 61.Nxc6 Kxc6 62.Rc5+ 1-0 6.4 Jaan Ehlvest 2605 Alfonso Romero Holmes 2485 Logrono tt 1991 1.e4 c5 2.Nc3 e6 3.Nf3 Nc6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 Nf6 6.Ndb5 Bb4 7.a3 Bxc3+ 8.Nxc3 d5 9.exd5 exd5 10.Bd3 0-0 11.0-0 Bg4 12.f3 Bh5 13.Bg5 Qb6+ 14.Kh1 Ne4 15.Nxe4 dxe4 16.Bxe4 Qxb2 17.Qb1 Qxb1 18.Rfxb1² f5 19.Bd3 b6 19...h6 20.Bd2 Ne5!? 21.Bf1! b6 22.Re1ƒ 20.Rb5 20.Re1 f4! is not entirely clear. 20...Bg6 20...Nd4 21.Rb4 Ne6 22.Be3 Bg6 prepares to trade the bishop pair with 23...f4, so only by anticipating the exchange with 23.Bf2!² can White retain his nibble. 21.Rd1 21.Rd5!? f4 22.Bxg6 hxg6 23.Rad1ƒ slightly limits Black’s options. 21...Rac8?! 21...h6!? 22.Bh4 Rae8 gives Black play with ...Ne5. 22.Rd5! Threatening 23.Ba6 and 24.Rd7. 22...f4 23.Bxg6 hxg6 24.h4± Rc7 25.Rd7 Rxd7 26.Rxd7 Rf5 27.Rd6!? This works well in the game, but it’s more restrictive to play 27.Rc7! Rc5 28.Bxf4 Rc4 29.Bg5 Rxc2 30.Be3 with a substantial advantage. 27...Ne5?! 27...Rc5! 28.Bxf4 Rc4 29.Bg5 Rxc2 30.Rxg6 b5² 28.Rd4 Nc6 29.Rc4! Na5 30.Rc8+ Rf8 31.Rxf8+ Kxf8 32.Bxf4 The extra pawn and superior minor piece decide the game (1-0, 62). 6.5 Stefan Wölfl 2212 Ioan Secrieru 2123 ICCF email 2011 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e6 6.Ndb5 Bb4 7.a3 Bxc3+ 8.Nxc3 d5 9.exd5 exd5 10.Bd3 0-0 11.0-0 d4 12.Ne2 a6 13.Bg5ƒ h6 13...Qd6 14.Qd2 Re8 15.Rfe1 Bd7 16.c3 exploits the absence of ...Rad8, winning a pawn after 16...Ne4 17.Bxe4 Rxe4 18.f3 Ree8 19.Bf4 Qd5 20.cxd4±. 13...Re8 14.Bh4 Qd6 15.c3! Bg4 16.f3 Bh5 17.cxd4² is similar. 14.Bh4 Re8 14...g5 15.Bg3 Re8 16.Re1± Ne4? 17.Nxd4! 15.Re1 Qd6 16.c3! Chess, like mathematics, is easy when you can follow a formula. 16...Bg4 17.f3 Bh5 17...Rad8 18.Qc2 dxc3 19.Rad1 puts Black under the pump, and after 19...Qc5+ 20.Bf2 Qh5 21.Ng3 Rxe1+ 22.Rxe1 Qd5 23.Rd1 Be6 24.Bh7+ Nxh7 25.Rxd5 Rxd5 26.bxc3± Black’s chances of constructing a fortress are minimal because of the opposite-coloured bishops. 18.Bf2 Rad8 19.Nxd4 Rxe1+ 20.Qxe1± My understanding of chess is that an extra pawn combined with another advantage is sufficient for victory with best play. Indeed, White won on the 61st move. 6.6 Mikhail Rytshagov 2495 Riho Liiva 2425 Tallinn rapid 1996 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e6 6.Ndb5 Bb4 7.a3 Bxc3+ 8.Nxc3 d5 9.exd5 exd5 10.Bd3 0-0 11.0-0 d4 12.Ne2 h6 13.b4 Bg4 14.Bb2 a6 15.f3 Be6 16.Kh1 Kh8 17.Qe1± Re8 17...Qb6 18.Qh4 Rfd8 19.Rad1 Rd7 20.c4 dxc3 21.Bxc3 Qd8 22.Bc2±; 17...Qd6 18.Qf2 Rad8 19.Rfd1± 18.Qf2 Ne5 As this is a rapid game, the players begin to commit inaccuracies. 19.Nxd4 19.Rfd1! Nxd3 20.Rxd3 Qc7 21.Nxd4± wins a pawn without disconnecting the queenside structure. 19...Nxd3 20.cxd3² Bd7?! Stronger was 20...Nd5. 21.Qd2?! 21.Nb3!? 21...Qe7 22.Rfe1 Qd6 23.Rxe8+ Rxe8 24.Re1 Rxe1+ 25.Qxe1 Nd5 26.Qe4 f6 27.Kg1 Nf4? This is a mistake based on a mutual oversight. 28.Kf2? 28.Qxb7! Nxd3? 29.Qa8+ Kh7 30.Qe4+ wins the steed. 28...Bc6! 29.Qe3 Bb5 30.Kg1 Nxd3 Now the game should be a draw, but fast time controls have an unpredictable nature. After many more adventures White won on move 83. 6.7 Alexander Motylev 2666 Zhang Pengxiang 2640 China tt 2008 (8) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Ndb5 Bb4 7.a3 Bxc3+ 8.Nxc3 d5 9.exd5 exd5 10.Bd3 0-0 11.0-0 d4 12.Ne2 Bg4 13.Bg5 Re8 14.Re1 Qd6 15.Qd2 Bxe2 16.Bf4 Qd5 17.Bxe2 17...Ne4 A) 17...Re7 18.Bf3 Ne4 19.Qd3 Rae8 20.Re2 f5 21.Rae1 g6 22.g4!±; B) 17...Rad8 18.Bf3 Qb5 19.b4 Qf5 (Nilsson-Limbert, email 2007) 20.Bg3! a6 21.Qd3ƒ The endgame with a symmetrical structure almost always favours White. 18.Bf3 This move gives up the bishop pair, so White should prefer 18.Qd3 Nc5 19.Qc4 Qf5 20.Bg3 when Black’s knights are unwieldy: 20...a6 (20...h6?! 21.b4 Ne6 22.Bd3 Qf6 23.Re4± was Tiviakov-Halkias, Amsterdam 2006) 21.Bf3 g6 22.Bxc6 bxc6 23.Rxe8+ Rxe8 24.f3 Qd5 25.Qxd5 cxd5 26.Kf1² 18...Qf5! 19.Qd3 Qxf4 20.Rxe4 Rxe4 21.Qxe4 21.Bxe4 g6 22.g3 Qf6 23.Re1 Re8 24.Kf1 a6= 21...Qc7 21...Qf6! keeps d4 protected, and after 22.b4 a6= White lacks an entry point. 22.Re1 22.h4!? 22...g6 23.h4! h5 24.Qd5 24.b4!? a6 25.Qd5 24...Kg7 25.Qc5 Rd8 26.b4 Qd6! 27.Qb5 27.Qg5!? would provoke the weakening 27...f6 28.Qb5. 27...Rd7 28.Bxc6 bxc6 29.Qg5 Qd5? Black could have waited, but now he encounters some tricks. 29...Rb7! 30.g3 Rb5= 30.Qe5+! Kg8? 30...Qxe5 31.Rxe5 d3 32.cxd3 Rxd3 33.Ra5 Rd7 34.Ra6 Rc7 35.Kh2 and Black is so passive that he will be lucky to make a draw. 31.Qf6!+– Rd8 32.Re5 Qd7 33.Re7 Qf5 34.Rxf7 Black resigned. 6.8 Igor Kurnosov 2602 Serikbay Temirbayev 2464 Khanty-Mansiysk 2009 (1) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e6 6.Ndb5 Bb4 7.a3 Bxc3+ 8.Nxc3 d5 9.exd5 exd5 10.Bd3 0-0 11.0-0 d4 12.Ne2 Qd5 13.Nf4 Qd6 14.Nh5 Nxh5 15.Qxh5 h6 16.Re1 Bd7 17.Qh4 Rfe8 18.Bf4 Qd5 19.f3² Rxe1+ 20.Rxe1 Re8 21.Rxe8+ Bxe8 Exchanging rooks is not so effective here as White’s bishop pair gains in strength with exchanges. 22.Qe1 22.Qg3!? Qe6 23.h4ƒ 22...Bd7 23.Qe4! Qxe4 24.Bxe4 g5 Over the next moves Black creates weaknesses in his structure; more solid is 24...f6² and advancing the king. 25.Bd6 f5?! Better was 25...Kg7 26.Kf2 f6. 26.Bd5+ Kg7 27.f4! Naturally we should fix the opponent’s weaknesses: 27.Kf2 f4 28.Be4 27...gxf4 27...Be8! 28.Kf2 Bf7 at least gets a bishop out of Black’s face. 28.Bxf4 h5 29.Kf2 Kf6 30.Kg3 b6 31.Bf3 31.Kh4!? Be8 32.Bg5+ Kg7 33.Bf3 Ne5 34.Bxh5 Bc6 35.Kg3± 31...Be8 32.Kh4 Black is unable to defend his weaknesses. 32...Na5 32...Ne5 33.Bxh5 Bc6 (33...Ba4 34.Bd1) 34.Bxe5+ Kxe5 35.Kg3+– 33.Be2! Bf7 34.b3 Bd5 35.g3 Be4 36.Bd1 Nc6 37.Kxh5+– a5 38.g4 38.Bc7! b5 39.h4 38...fxg4 39.Kxg4 Ne5+ 40.Bxe5+ Kxe5 41.h4 b5 42.h5 b4 43.axb4 axb4 44.Kg5 Bf5 45.h6 Be4 46.Bh5 Bxc2 47.Bg6 1-0 Chapter 7 The Taimanov 4...Nc6 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 2...Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Qc7 merely transposes to the normal Taimanov after 5.Nc3 e6. It was only a few years ago that the solid, flexible Taimanov was one of the three main replies to the Open Sicilian, but some fresh developments have dealt a serious blow to its popularity at the highest level. 5.Nc3 Qc7 The sub-optimal 5...d6 will be covered under the Scheveningen chapter. 5...a6 6.Be3 (this is the most consistent, but 6.Nxc6 bxc6 7.Bd3 is the route to a white edge: 7...d5 8.0-0 Nf6 9.Qf3 Be7 10.Qg3 0-0 11.Bh6 Ne8 12.Bf4 Bh4 13.Qf3 Bg5 14.Na4 Bxf4 15.Qxf4 Qc7 In Bobras-Bai, Germany Bundesliga 2015/16, I show that White was successful with 16.e5, but I prefer 16.Qxc7!? Nxc7 17.c4 with a very stable endgame advantage due to the passive c8-bishop) 6...Nf6 (this alternative move order is surprisingly annoying for White. On 6...Nge7, 7.Nb3!² is the typical counter, depriving Black of his ...Nxd4/...Nc6 exchanging plan. See Lopez MartinezKhamrakulov) 7.Qf3!? (Black is not forced to transpose to the main line with 7...Qc7) 7...d6!? (Gajewski’s 7...Bd6 8.00-0 Be5 feels a bit artificial if White plays directly: 9.g4! d6 10.g5 Nd7 11.h4 0-0 12.Kb1ƒ; for 7...Bb4 see Grischuk-Grachev, Sochi 2017) and now: A) 8.Nxc6 bxc6 is a good version of this structure for Black, as he didn’t spend a tempo on ...Qc7: 9.0-0-0 (normal development also doesn’t suffice for a plus: 9.Be2 Be7 10.Qg3 0-0 11.0-0-0 Qc7=) 9...e5 10.h3 Be6 11.g4 h6=; B) 8.0-0-0 Bd7 is a very decent attempt I played in blitz a couple of years ago – the point is that 9.g4 now loses a pawn to ...Ne5: B1) 9.Qg3 Nxd4 10.Bxd4 (or 10.Rxd4 Rc8 11.f3 Be7 12.h4 0-0 13.h5 Rxc3! – this exchange sacrifice is extremely unpleasant: 14.bxc3 Qa5 15.Rb4 Rc8 16.h6 g6° and I would already prefer Black’s chances) 10...e5 11.Be3 Be7 12.Bg5 Be6 13.Bxf6 Bxf6 14.Nd5 The play resembles the Najdorf chapters, but 14...Rc8 15.Be2 Bg5+ 16.Kb1 0-0 17.h4 Bh6 18.Qb3 Qd7 19.g4 Bf4= looks fine for Black; B2) 9.Nxc6!? Bxc6 10.g4 (10.Bd3 b5 11.Rhe1 Be7 12.Kb1 is playable but would not perturb me as Black) 10...b5 11.g5 Nd7 12.Kb1 Qc7 Compared to analogous lines, Black is faster with his queenside counterplay. To give an example: 13.h4 Ne5 14.Qg2 Qb7 15.Rd4 a5 16.h5 b4 17.Ne2 a4 18.f4 Nd7 19.Ng3 d5 20.exd5 Bxd5 21.Rxd5 Qxd5 22.Qxd5 exd5 23.Bd4 Rg8 with sufficient compensation for the exchange. 6.Be3 a6 6...Nf6 7.Qf3 leaves nothing better than 7...a6, transposing to the main lines, as otherwise Ndb5 and Qg3 transitions to a promising endgame: 7...Bb4 (7...d6 8.0-0-0 forces 8...a6, else Ndb5 and Qg3 will hurt) 8.Ndb5 Qb8 9.a3 Be7 10.Qg3 Qxg3 11.hxg3² 7.Qf3! This more active development replaced the English Attack as the main line a couple of years ago, as White won several theoretically important games. The book Attacking the Flexible Sicilian (henceforth ATFS) by Vassilios Kotronias & Semko Semkov recently made the case for a white advantage, but I have some ideas of my own. Actually, the Taimanov was my main defence to 1.e4 two years ago, but I ditched it because of 7.Qf3. 7th move sidelines A) The trappy 7...Ba3? 8.0-0-0 Ne5 9.Qg3 Qxc3 10.bxa3 Qxa3+ 11.Kb1 Ng6 12.Nb3! was much better for White in Smirnov-Nguyen, Kuala Lumpur 2015, as Black is unable to avoid dark-squared penetration with Bc5; B) 7...Nge7 8.Nb3!N avoids Black’s exchange, and after 8...Ng6 9.0-0-0ƒ Black struggles for a plan; C) 7...Bb4 8.Qg3!? (8.Nxc6 bxc6 9.Bd4² is ATFS’s main line) 8...Qxg3 9.hxg3 Nf6 10.Nxc6 bxc6 11.e5 Nd5 12.Bd2 favours White, as the c8-bishop is stuck after 12...Nxc3 13.bxc3 Be7 14.Rb1²; D) 7...Nxd4 8.Bxd4 b5 9.Qg3 Qxg3 10.hxg3 transposes to 7...b5; E) 7...b5 8.Qg3 Qxg3 9.hxg3 is an unpleasant endgame for Black, due to White’s lead in development: 9...Nxd4 (9...Bb7 10.Nb3! Nf6 11.f3 d5 12.exd5 Nb4 13.0-0-0 Nfxd5 14.Nxd5 Bxd5 15.Kb1 gave White some pressure in BokSpoelman, Amsterdam 2015. Even the deviation 15...Rc8 16.c3 Nc6 17.Bd3 h6 18.g4² is no picnic) 10.Bxd4 Bb7 (10...Ne7 11.f3 Nc6 12.Bb6!? Rb8 13.Bf2² is a funny twist, when Black loses the option to castle queenside) 11.f3 11...Ne7 (after 11...Rc8 12.a4! b4 13.Nd1 it would be too risky for Black to take on c2, but 13...Ne7 14.Ne3 Nc6 15.Bb6² also brings up Black’s queenside weaknesses) 12.0-0-0 Nc6 (12...d5 13.exd5 Nxd5 14.Bd3 h6 is the reason in ATFS for preferring 12.g4, but 15.a3!? Nxc3 16.Bxc3 Rc8 17.Be5 continues to pose problems for Black, who will have to deal with the pressure on g7) 13.Be3 Rc8 (13...h6 14.a4N 14...b4 15.Nb1² and Nd2-c4 favours White, as Black’s structure is inferior) 14.Kb1 Na5 15.g4 f6 16.Bb6!? Nc4 17.Bd4 White wants to play Bxc4 and e5 to weaken Black’s structure. If 17...e5 18.Bxc4 Rxc4 19.Be3 Bc5 20.Bxc5 Rxc5 21.Rd3! followed by Nd1-e3, Black remains positionally worse. The Giri Variation The cavalier 7...Ne5 8.Qg3 h5 was essayed several times by Giri before mysteriously disappearing off the radar. 9.h4!? This move is covered in ATFS, but I found a completely new interpretation for White based on Bxb5 sacs: A) 9...d6 10.0-0-0 Bd7 11.Bg5! b5 12.a3ƒ and f2-f4 gives White a strong initiative; B) 9...Nf6 10.0-0-0 b5 (10...d6 offers up an opportunity for 11.Be2! b5 (11...Be7 12.Bg5! is an improved version of normal lines for White, e.g. 12...b5 13.f4 Neg4 14.a3 Bb7 15.Bf3 0-0 16.Rhe1ƒ and Black’s kingside fulcrum is about to be exchanged off) 12.f4 Nc4 13.e5!N (White is well ahead in development, so complications are likely to be in his favour) 13...Ng4 14.Bxc4 Qxc4 15.exd6 Bxd6 16.Ndxb5 axb5 17.Rxd6 0-0 18.Rd4 Qc5 19.Ra4 Qc6 20.Rxa8 Qxa8 21.Bc5 Rd8 22.a3² White is up a pawn and Black doesn’t have enough of an initiative for it) 11.Bxb5 (this is more an exchange of material than a sacrifice) 11...axb5 12.Ndxb5 Qb8 13.Bf4 d6 14.Nxd6+ Bxd6 15.Rxd6 Qxd6 16.Bxe5 Qc5 17.b4! This deflection is the basis of my recommendation. 17...Qxb4 18.Qxg7 Rg8 (weaker is the spite check 18...Qa3+ 19.Kd2 Qf8 20.Qxf8+ Rxf8 21.Bxf6±) 19.Qxf6 Rg6 Black must continue to be accurate to avoid a dark-squared bind (19...Ra7 20.Ne2! Rb7 21.Bb2 Rxg2 22.Nf4 Rxf2 23.Qh8+ Qf8 24.Qc3 Bd7 25.Qe3 Rxf4 26.Qxf4² ends with a material advantage for White): 20.Qh8+ Qf8 21.Qxf8+ Kxf8 22.g3 f6 23.Bd6+ Ke8 24.Rd1ƒ The endgame should be a draw with correct play, but White has a small material advantage and the opposite-coloured bishops mean that the play will continue for some time; C) 9...b5 10.0-0-0 d6 11.Bf4!? (11.a3 Nf6 12.Bg5 is recommended in ATFS) 11...Nf6 (11...b4? 12.Ncb5! axb5 13.Bxe5 dxe5 14.Bxb5+ Bd7 15.Nxe6 fxe6 16.Rxd7 was crushing in Mons-Hoolt, Germany Bundesliga 2014/15) 12.Bxb5+ axb5 13.Ndxb5 Qc5 14.Rxd6! and now: C1) 14...Rxa2 15.b4! Ra1+ 16.Kb2 Qxb4+ 17.Kxa1 favours White after some crazy variations: 17...Nc4 (or 17...Bxd6 18.Qxg7 Qa5+ 19.Kb1 Qb4+ 20.Kc1 Nd3+ 21.cxd3 Bxf4+ 22.Kc2 Rh6 23.e5!±) 18.Rb1 Qa5+ 19.Na2 Nxe4 20.Rc6! Nxg3 21.Rxc8+ Ke7 22.Rxc4 Nf5 23.Nbc3 (the pieces coordinate extremely well in attacking Black’s king) 23...e5 24.Rb5 Qxb5 (24...Qa8? 25.Nd5+ Kd8 26.Bd2!± and Ba5 is unpleasant) 25.Nxb5 exf4 26.Rxf4 g6 27.Nb4 The extra pawn gives some winning chances in the endgame; C2) 14...Bxd6 15.Nxd6+ Kf8!? (15...Qxd6 transposes to the 9...Nf6 move order) 16.Nxc8 Nfg4 17.Nd6! Qxd6 18.f3 Qb6 19.Bxe5!? (19.fxg4 Nxg4 20.Rd1 Kg8 21.b3 Kh7 22.Kb2 was my initial idea, but the computer maintains that 22...Rhc8! maintains the balance with accurate play) 19...Nxe5 20.Qxe5 Rh6! 21.Qh2!? Rg6 22.Qg1 Qb4 23.Qf2 Kg8 The engine gives 0.00, but the position looks better for White from a human perspective, with three healthy pawns for the exchange. Scheveningen style 7...d6 was recommended by Robin van Kampen in his Taimanov video series, but has since come under considerable pressure, as the queen proves quite flexible on f3. The exchange 8.Nxc6 makes sense when Black can’t recapture with the d-pawn or bishop: A) 8...Qxc6 9.Bd3 (9.a3!?N is a prophylactic idea I found in 2016, which looks good for an edge too. If 9...Nf6 10.g4! b5 11.g5 Nd7 12.Qg3 looks like a promising h3 Najdorf for White; 9.Be2N might also be explored, to meet ...b7-b5 with a later Bf3) 9...Nf6 10.Qg3! b5 11.f3² I second ATFS’s recommendation as here we don’t even need to spend a tempo on a2-a3. Furthermore, subsequent practical games have been successful for White, see Bok-Leenhouts, Netherlands tt 2016/17; B) 8...bxc6 9.0-0-0 With this move order, we keep both g2-g4 and Qg3 as options. B1) 9...Nf6 10.g4! It’s already hard for Black to avoid a clear disadvantage. 10...h5 (10...Nd7 11.Qg3 Rb8 12.g5! Be7 13.h4 Qb7 14.b3 gives White an obvious attack; opening the centre with 10...d5?! 11.Bg2 Be7 12.g5 dxe4 13.Qg3!? Qxg3 14.hxg3 Nd5 15.Bxe4 is disastrous for Black) 11.g5 Ng4 12.Bf4 Be7 13.Be2 Ne5 14.Bxe5 dxe5 15.g6 fxg6 16.Qg3 g5 17.h4! was unbelievably good for White in Gomez Galan Arense-Roy Laguens, email 2014; B2) 9...Rb8 10.Qg3 Nf6 11.Be2!? (11.f4 is ATFS’s main line, based on 11...g6 12.e5 Nh5 13.Qf2 d5 14.g4 Ng7 15.Ba7 Rb7 16.Bc5 Qa5 17.Bxf8 Kxf8 18.Rd4! c5 19.Ra4 Qb6 20.b3ƒ and only now does the engine realise the bind Black is in) 11...Be7 12.h4 I will demonstrate White’s advantage in the game Doderer-Krause, email 2013. Black’s best reply 7...Bd6!? 8.0-0-0 Be5 is a solid line that continues to be employed by strong players. A) 9.g3 forces considerable accuracy from Black: A1) 9...Nf6 only places the knight in reach of Qe2/f2-f4/e4-e5: 10.Qe2 0-0 (Black should probably opt for 10...d6 11.Bg2!? Nxd4 12.Bxd4 b5 13.f4 Bxd4 14.Rxd4 e5 15.Rd2²) 11.f4 Bxd4 12.Bxd4 Nxd4 13.Rxd4 e5 (13...d6 14.Qc4!± is a powerful novelty given in ATFS) 14.fxe5 Qxe5 15.Qd2 b5 16.Bg2 Bb7 17.Rf1 and Rd6, with an obvious positional advantage; A2) 9...Nge7 10.Qe2 The key idea for White is to delay f2-f4 in favour of Qd2!, which has hardly been tested, but continues to be developed in the grandmaster kitchen. A21) 10...b5 11.Qd2 (11.f4 Nxd4 12.Bxd4 Bxd4 13.Rxd4 Nc6 14.Nd5 Qa5 15.Rd3 0-0 16.Ra3 Qd8 17.Ne3 Qb6 18.Kb1ƒ) and now: 11...Bb7!?N (11...Rb8 12.f4 Bxd4 13.Bxd4 Nxd4 14.Qxd4 0-0 15.a3!?² is more comfortable for White, as Black’s ...f7-f5 break is quite double-edged; 11...Nxd4 12.Bxd4 Bxd4 13.Qxd4 0-0 transposes to 10...0-0) 12.Nb3! (12.Nf3 Bxc3 13.Qxc3 0-0 14.Bf4 Qd8 15.Bd6 Re8 16.Bg2 looks better for White, but Black can play around the d6-bishop without grief: 16...Rc8 17.Qd2 Na5 18.Ne5 f6 19.Bb4 Nec6 20.Nxc6 Nxc6 21.Bd6 Qb6=) 12...d6 13.f4 Bxc3 14.Qxc3 0-0 15.a3!? (it doesn’t make much sense to place the bishop on g2, but stopping Black’s queenside counterplay by keeping the bishop on d3 fits) 15...Rfc8 16.Bd3 d5 17.Rhe1 dxe4 (the optimistic 17...a5 18.Bxb5 dxe4 19.Bg1 Nd5 20.Qd2 a4?! 21.Nc5 leaves Black short of tricks) 18.Bxe4 Na5 19.Bxh7+ Kxh7 20.Nxa5 Qxc3 21.bxc3 Bf3 22.Rd7 Nf5 23.Rxf7 Rxc3 24.Bd2 Rxa3 25.Rc7!² White has the initiative, which is everything with the oppositecoloured bishops; A22) 10...0-0 11.Qd2!N This prophylaxis against the ...Nxd4, ...Bxd4 and ...e6-e5 idea was first mentioned by Avrukh on the CHOPIN opening website: A221) 11...d5 12.Nxc6 bxc6 13.f4 Bd6 14.Na4 e5 15.Bb6 Qb8 16.f5 (Avrukh) 16...Bd7 17.Bc5²; A222) 11...b5 12.Nxc6 Qxc6 13.Bg2 Bc7 14.Kb1 d6 15.f4 Re8 (15...Bb7 16.Ne2 Bb6 17.Bxb6 Qxb6 18.Qd4 Qxd4 19.Rxd4 is a nice endgame for White) 16.e5 d5 17.Ne2² White has achieved a nice Steinitz French, with a kingside pawn storm to follow; A223) 11...Nxd4 12.Bxd4 Bxd4 13.Qxd4 b5 14.Qd6 Qxd6 15.Rxd6 Rd8 16.Rb6! Nc6 (similar is 16...Ra7 17.a4 bxa4 18.Nxa4 d5 19.Bg2 dxe4 20.Bxe4²) 17.Bg2 Rb8 18.Rxb8 Nxb8 19.e5 d6 20.exd6 Rxd6 21.Rd1 Rxd1+ 22.Nxd1 Kf8 23.c4 Bd7 24.Kc2² As pointed out in ATFS, Black is far from a draw, as his pieces are a bit passive and White has the outside majority. A3) 9...b5! I was unable to prove an edge against this rare move order: 10.Qe2 (10.Nxc6 Qxc6 11.Bd4 Bxd4 12.Rxd4 Qc5!= is an improved version for Black) 10...Bb7 11.f4 (11.Bg2 b4!) 11...Nxd4 12.Bxd4 Bxd4 13.Rxd4 Qc5 14.Qd2 Bc6 15.Bg2 b4 16.Nd1 a5 was noted in ATFS as favouring White, but I have not found a way to utilise White’s space and mobilisation, due to the fixed structure: 17.Ne3 Ne7 18.Kb1 (endgames are generally fine for Black: 18.Rc4 Qa7 19.Qd4 0-0 20.Qxa7 Rxa7=; 18.Nc4 is given by Avrukh, but 18...0-0! 19.Ne5 Rfd8 20.Rd1 Rac8 21.Rc4 Qb6 is quite sound for Black) 18...0-0 19.Rd1 Rab8 (19...f6!? 20.h4 Rab8 21.Rc4 Qb6 22.Bh3 a4 is similar, in that White has more space but no real advantage) 20.e5 a4 21.Be4 Bxe4 22.Rxe4 Nc6 White is definitely pressing with the d6-pawn a longterm target, but Black is holding his own here. B) 9.Nxc6 is the simplest approach: 9...bxc6 10.Bd4 The key motif to remember is that we’re playing Qe3 and f2-f4. B1) 10...Nf6 11.Bxe5 Qxe5 12.Qe3! The engines initially don’t think much of this, but they recommend ...Nf6-g4-f6, which you’re unlikely to see over the board: B11) 12...0-0 13.f4 Qc7 14.e5 Nd5 15.Qd4 is a very desirable structure for White: 15...Rb8!? (15...f6 16.Bd3 Nxc3 17.Qxc3 fxe5 18.Qxe5² will lead to a better endgame or middlegame) 16.Bc4 Qa5 17.Rhf1! c5 18.Qd3 Nxc3 19.Qxc3 Qxc3 20.bxc3 – as is often the case, the endgame favours White because of Black’s awful c8-bishop; B12) 12...Ng4 13.Qe1 Black is unable to equalise, as shown in Vishnu-Bogner, Gibraltar 2015 (13.Qe2 Nf6!? is not easy to crack, e.g. 14.g3 d5 15.f4 Qc7 16.Bg2 0-0 17.Rhe1 Rb8 18.b3 Bb7 and White has a small edge but nothing special). B2) 10...Bxd4 11.Rxd4 Nf6 (11...Ne7?! 12.Qg3 Qxg3 13.hxg3 d5 14.Na4 e5 15.Rd1 Rb8 16.Nc5± was the ideal version of this endgame in Grigoryan-Miladinovic, Kragujevac 2016) 12.Qe3! Ng4 (12...e5 13.Rd2 0-0 14.Qc5!² ensures the better structure for White) 13.Qe2 Black’s choice of retreat will determine the nature of the play, but in all cases White holds a plus: B21) 13...Ne5 14.f4 Ng6 15.e5 0-0 16.g3 f6 17.exf6 gxf6 18.Bh3 e5 19.Ra4 d5 20.Bxc8 Qxc8 (Gurinov-Szymanki, email 2011) 21.b3!? is a bit better for White, due to his safer king in a position with mostly major pieces; B22) 13...Nf6!? 14.e5 Nd5 15.Nxd5 cxd5 (15...exd5 is met the same way) 16.Qe3 Rb8 17.Bd3 is a quite comfortable game for White, with the better bishop and easier attack; B23) 13...Nh6 14.f3 f6 15.Qe3 0-0 16.Rd2 Nf7 17.Be2 Bb7 18.Rhd1 d6 19.f4² White has more space and decent attacking chances. The most common move 7...Nf6 The most common move, though trends tend to vary frequently in nascent lines. 8.0-0-0 Ne5 Black has various alternatives here, but I don’t find any of them particularly enticing: A) 8...h5?! is the poor cousin of the Giri Variation, and well parried by 9.Nxc6 dxc6 10.h3 b5 11.e5 Nd5 12.Bf4². The only question then is 12...Qa5 (ATFS analyses several other moves, but positionally it doesn’t make much sense to stay in this structure and allow Ne4-d6; e.g. 12...Nxc3 13.Qxc3 c5 14.Be2 Bb7 15.Rd6! favours White) 13.Bd3! b4 14.Nxd5 cxd5, but this structure is a turbocharged French for White after 15.Kb1 Bd7 16.g4 (if 16.Qg3 Qc7! 17.Rc1 Rb8 stops c2-c3, and after the a-pawn advance it’s not so easy to prove White’s advantage) 16...hxg4 17.hxg4 Rxh1 18.Rxh1ƒ; B) Black should avoid 8...b5?! 9.e5! b4 10.exf6 bxc3 11.Nxc6 cxb2+ 12.Kb1 Qxc6 13.Qxc6 dxc6 14.Bd4 g6 15.h4± Low-Himanshu, Bangkok 2017; C) Among Black’s typical mistakes is 8...Bb4?! 9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.Bd4 and Black was already in trouble in CaruanaRublevsky, Olginka 2011 – incidentally one of the first GM games with the Qf3 set-up, which excuses the inaccuracies in the subsequent play; D) 8...d6 9.Nxc6 Qxc6 (9...bxc6 transposes to 7...d6) 10.Be2! can transpose to 8...Be7 after 10...Be7 11.Kb1. Instead, 10...Nd7 (or 10...Qc7 11.g4!) 11.Qg3 b5 12.a3 Bb7 13.Bf4! e5 14.Be3 gave White a clear advantage in the model game Tari-Movsesian, Reykjavik 2015; E) 8...Be7 9.Kb1!ƒ is another line where Black has been getting clobbered: E1) 9...h5 10.Be2 b5 11.Nxc6 dxc6 12.e5 Nd5 13.Qg3 g6 14.h4 Nxc3+ 15.bxc3 Bb7 16.Rd6!± is a lovely variation by Kotronias/Semkov; E2) 9...Nxd4 10.Bxd4 d6 11.Qg3± Vetoshko-Zpevak, Slovakia tt 2016/17, was the latest depressing example for Black; E3) 9...d6 10.Nxc6 bxc6 11.g4 Rb8 12.g5 Nd7 13.Qg3± was the model game Popov-Lazarev, Chennai 2015; E4) 9...0-0 10.g4!± (Black can hardly accept the sacrifice with 10...Ne5 now that he’s castled) E41) 10...d5!? 11.exd5 Nxd5 12.Nxd5 exd5 13.Bg2 Be6 is a promising anti-IQP position for White, but we might even transform our advantage: 14.Nxe6!? fxe6 15.Qe2 Rae8 16.f4² with the bishop pair and the superior structure. Note that 16...Bd6 does not win a pawn: 17.Rhf1 Bxf4?! 18.Bxf4 Rxf4 19.Rxf4 Qxf4 20.Bxd5±; E42) For 10...Nxd4 11.Bxd4 b5 see Lugovskoy-Jumabayev, Riga 2015; E43) 10...b5 11.g5 Ne8 12.Nxc6 Qxc6 13.Bd3 f5?! (but otherwise White’s attack plays itself) 14.Qh3± was already very menacing in Praneeth-Tarini, Noida 2016; E44) 10...d6 11.Nxc6 Qxc6 (11...bxc6 is also a great structure for White, as already noted in ATFS: 12.g5 Ne8 13.h4 Rb8 14.b3 d5 15.Bf4 Bd6 16.Bxd6 Qxd6 17.Qe3 and White’s attack will be faster) This is the one line where we shouldn’t automatically play g4-g5/h2-h4, as ...f7-f5 may give Black counterplay. 12.Qh3! This move is particularly unpleasant, as White is ready for g5 and f4-f5, while the attempt to create counterplay with 12...b5?! fails to 13.e5! Nd5 14.Nxd5 exd5 15.Bg2 Be6 16.f4± and f4-f5 will be killing; F) 8...Nxd4 9.Bxd4 e5 10.Be3 d6 11.Qg3 Be6 (or 11...b5 12.f4 Bb7 13.Kb1!N 13...Be7 14.Qxg7 Rg8 15.Qh6 Rg6 16.Qh3 Nxe4 17.Nxe4 Bxe4 18.Rd2± with the much safer king) 12.Bg5 Be7 13.Bxf6 Bxf6 14.Nd5 Bxd5 15.Rxd5 resembles our 6.h3 Najdorf line, and in Salem-Hossain, Baku 2016, White eventually converted his risk-free edge into a win. 9.Qg3 b5 This active approach was a main line a couple of years ago, but has fallen under a cloud since. 10.f4 Neg4 11.Bg1! b4 11...h5 12.e5 b4 13.Na4 (13.Nb1!?) 13...Nd5 transposes to Fier-Leenhouts, Amsterdam 2017. 12.Na4 Nh6 I really like ATFS’s main recommendation against this move. For 12...h5! 13.e5 Nd5 14.h3 Nh6 15.Bd3² see Fier-Leenhouts. 13.e5! Nd5 14.Kb1 Bb7 15.b3!N 15...Rc8 15...g6 16.Bc4 Bg7 17.h4! d6 18.Re1 dxe5 19.fxe5 and h4-h5 offers a strong initiative. 16.Bc4 By blockading the queenside, White maintains control of the play. 16...g6 The retreat 16...Ng8 17.f5 Nge7 18.Qd3 Nf4 19.Qd2 Nfd5 20.h4 is ATFS’s main line, but it should be explained that 20...Qxe5?! is too risky: 21.Re1 Qc7 22.Bh2 Qa5 23.fxe6 dxe6 24.Nxe6! fxe6 25.Rxe6± and I doubt Black will survive this attack. 17.h4 d6 18.exd6 Bxd6 19.h5 White will play Qe1 next to set up Nxe6, with the exception 19...Bxf4 20.Qh3!± Summary 2...e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3: 5...a6 6.Nxc6 – +0.30 6.Be3 – +0.25 5...Qc7 6.Be3 a6 7.Qf3: 7...b5 – +0.30 7...Ne5 – +0.30 7...d6 – +0.35 7...Bd6 – +0.25 7...Nf6 – +0.30 7.1 Piotr Bobras 2531 Jinshi Bai 2519 Germany Bundesliga 2015/16 (2) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Nxc6 bxc6 7.Bd3 d5 7...Qc7 transposes to the Paulsen chapter. 8.0-0 Nf6 9.Qf3! 9.Re1 9...Be7 9...Bb7 10.Re1 Be7 11.Qg3 Kf8 12.h3!?N 10.Qg3 0-0 10...Nh5 11.Qg4 g6 12.Bh6² 11.Bh6 Ne8 12.Bf4 As in the 7.Qf3 Taimanov, the queen is quite mobile from g3. 12...Bh4 12...Ra7!?N 13.Rad1 Rd7 14.Rfe1 Bb7 15.Na4² is a lukewarm setup for Black. 12...a5 13.Na4 Ba6 14.Rad1 Bxd3 15.cxd3² has scored 3/3 in practice, most notably in Pfiffner-Kalinin, email 2012, where the backward c6-pawn factored. 13.Qf3 Bg5 13...Be7 14.Rad1 Nf6 15.h3² 14.Na4 Bxf4 15.Qxf4² Qc7 16.e5 Nf6 16...c5 17.Qe3 c4 18.Be2² 17.Rfe1 Nd7 18.c4 a5 19.cxd5 Black would be more passive if White retained the tension with 19.Rac1 Ba6 20.b3ƒ. 19...cxd5 20.Rac1 Qb8 21.Rc6 Ra7 21...Qb7 22.Rd6 Qb4 23.Qxb4 axb4 24.b3² 22.Qe3! Rc7 23.Rxc7 Qxc7 24.f4ƒ Ba6?! Black should have bid his time with 24...Qb7!?. 25.Bxa6 Qc6 26.Qe2 Qxa4 27.Bb5 Qd4+ 28.Qf2 Qxf2+ 29.Kxf2± Nb6 29...Nc5 30.Rc1 Ne4+ 31.Ke3 Rb8 32.a4± 30.Rc1 Rb8 31.b3 d4?! 31...h6 32.Rc7 32.Rc5 Kf8 33.Bc4 33.Kf3!? 33...Nxc4 34.Rxc4 g5 35.Rxd4 Now the rook endgame is trickier to win, whereas 35.fxg5 Rb5 36.Rxd4 Rxe5 37.h4± was more prosaic. White eventually made it on move 85 (1-0). 7.2 Josep Manuel Lopez Martinez 2563 Ibragim Khamrakulov 2545 Benidorm 2007 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3 Ne7 6.Be3 Nbc6 7.Nb3!² Ng6 A) 7...d5 8.exd5 Nxd5 9.Nxd5 exd5 10.g3 Be6 11.Bg2ƒ; B) 7...d6 8.Be2 b5 9.f4 Ng6 10.Qd2 Be7 11.0-0-0ƒ; C) 7...b5 8.a4 b4 9.a5! and Bb6 is a stock trick. 9...Nxa5 (9...d6 10.Na4 Bb7 11.Nb6 Rb8 12.Qd3±) 10.Na4 Nec6 11.Nxa5 Nxa5 12.Bb6 Qg5 13.g3± White’s threats persist into the middlegame. 8.Qd2 b5 8...Be7 9.f4 d6 10.0-0-0 b5 11.Kb1± 9.0-0-0 After 9.f4! d6 10.0-0-0 Bb7 11.Qf2!?± it becomes clear how misplaced the g6-knight is. 9...Nge5 10.f4 Nc4 11.Bxc4 bxc4 12.Nc5± Rb8 12...d6 13.N5a4 Rb8 14.Qe2± 13.e5 Qa5? 13...Qb6 14.N5a4 Qc7 was the only way to avoid material losses. 14.Nxd7 Rxb2 15.Nxf8+– Rb7 15...Qa3 16.Qd6! 16.Qd6 Ne7 17.Na4 f6 18.exf6 gxf6 19.Nb6 c3 20.Qc5 Qxa2 21.Qxc3 Rxf8 22.Bc5 Rc7 23.Rd8+ Kf7 24.Rxf8+ Kxf8 25.Qxf6+ Ke8 26.Qh8+ Kf7 27.Qxh7+ Ke8 28.Qh8+ Kf7 29.Nxc8 Nf5 30.Qh7+ Ng7 31.Nd6+ 1-0 7.3 Alexander Grischuk 2750 Boris Grachev 2658 Russia tt 2017 (4) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 Nf6 7.Qf3 Bb4 8.Nxc6 dxc6 8...bxc6 9.Qg3!? 0-0 (9...Nh5 10.Qg4 Nf6 11.Qxg7 Rg8 12.Qh6 Nxe4 13.Qxh7 Nf6 14.Qd3²) 10.Bd3 (this position suits White as the bishop doesn’t really belong on b4) 10...e5!? (10...d5 11.e5 Ne8 12.0-0 Be7 13.Na4 d4 14.Bh6 c5 15.b3ƒ would be a typical strategic advantage, as Black’s pawns are fixed) 11.0-0 Qe7?! (11...Re8 12.Bg5!²; 11...d6 12.Na4!²) 12.Bg5 Qe6 13.Bc4! (Lugovskoy-Belous, St Petersburg 2015) 13...Nh5 14.Bxe6 Nxg3 15.Bxf7+ Kxf7 16.hxg3 Bxc3 17.bxc3² 9.a3! 9.Qg3 0-0 10.Bd3 Qa5 11.0-0 e5 12.Bh6 Ne8 13.Bd2 Bd6! 14.a3 Qc7= 9...Bxc3+ 10.bxc3 Qa5 11.Bd2 0-0 12.Bd3 e5 13.a4² White will shortly fix Black’s queenside pawns with c3-c4 and a4-a5. 13...Be6 13...Nd7 14.0-0 Nc5 15.Qe3 Nxd3 16.cxd3 Be6 17.c4 Qc7 18.Bb4 Rfc8 19.a5 c5 20.Bc3² 14.c4 Qc7 15.a5! c5 16.0-0 Nd7 17.Rfb1 Rab8 18.Rb3 18.Qg3!? 18...Qd6 19.h3 b5 19...Bxc4!? 20.Bxc4 Qxd2 changes the position, but 21.Qd3! Qxd3 22.cxd3 b5 23.axb6 Rxb6 24.Rba3 Nb8 25.Ra5 Rc8 26.h4 retains control and leaves Black short of a clear draw. 20.axb6 Rxb6 21.Rba3!ƒ Rfb8 22.Kh2 22.Qd1 makes sense as the queen is the one piece not performing an obvious function. 22...f6 23.Qg3 23.Qe3!? Bf7 24.Ra5 23...Bf7 24.Bh6 Bg6 25.Be3 Qc6 26.Qg4 26.f3 26...Nf8 27.Ra5 Ne6 28.h4! Be8 29.h5 Bd7 30.Qg3² Bc8 30...Qd6 was better, to prevent the opening of the kingside. 31.f4 31.h6! g6 32.f4 31...exf4 32.Bxf4 Nxf4 33.Qxf4 Rb1? Blundering a nice interference tactic; 33...h6 was indicated. 34.Rb5! Rxa1 34...axb5 35.Rxb1 35.Rxb8 Kf7 36.Qg3+– Qd7 37.e5 fxe5 38.Bxh7 Qg4 39.Bg6+ Kf6 40.Rb6+ Kg5 41.Qxe5+ Bf5 42.Bxf5 1-0 7.4 Benjamin Bok 2554 Wouter Spoelman 2583 Amsterdam ch-NED 2015 (6) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Be3 a6 7.Qf3 b5 8.Qg3 Qxg3 9.hxg3 Bb7 10.Nb3 Nf6 11.f3 d5 12.exd5 Nb4 13.0-0-0 Nfxd5 14.Nxd5 Bxd5 15.Kb1² h6 16.c3 This is a little rushed; I would prefer 16.g4 f6 17.c3 Nc6 18.g5 fxg5 19.Bxg5 (ATFS) 19...Kf7 20.Bd3 Ne5² or 16.Be2!? Be7 (16...f6!?) 17.c3 Nc6 18.Nc5 Bxc5 19.Bxc5² with an extra tempo on the game. 16...Nc6 17.Nc5 Bxc5 18.Bxc5 0-0-0 18...f6! (ATFS) 19.b3 Ne7 gives Black reasonable coordination to deal with the bishop pair. 19.Be2 19.Bd3!?ƒ 19...Kb7 20.b3 e5 21.g4ƒ Be6 21...f6 22.Kc1 f6 The remaining play was pretty good for a rapid game. 23.Rxd8 23.Bd3! Rhg8 24.Be4 23...Rxd8?! 23...Nxd8! 24.Rd1 Kc6 25.Be3 Nf7= 24.Rd1 Bf7 25.Bd3± h5 26.gxh5 Bxh5 27.Bf5 White wants to keep Black’s pawns fixed. 27.Be4 Kc7 28.Rh1 Bf7 29.Rh7 Rg8² 27...Rxd1+ 28.Kxd1 Bf7 28...Be8! 29.Be4 g6 30.g4 Kc7 31.Bf8 Nb8 32.Be7 Nd7 33.Kc2± g5 34.Kd3 Be6 35.Ke3?! Here the king is vulnerable to a later ...Nb6-d5, so the right square is 35.Ke2! a5 36.Bd3. 35...a5 36.Bg6?! 36.Bd3 Nb6!; 36.Kf2! 36...Nb6! 37.Bxf6 White could still have retracted with 37.Be4! Nd7 38.Kf2!. 37...Nd5+ 38.Ke4 Nxf6+ 39.Kxe5 Bxg4 40.fxg4 40.Kxf6 Bxf3 41.Kxg5 Bd5= 40...Nxg4+ 41.Kd5 Kb6 42.Kd6 Ne3= 43.Bd3 g4 44.c4 bxc4 45.bxc4 g3 46.c5+ Ka7 47.Be4 Nc4+ 47...g2 48.Bxg2 Nxg2 49.c6 Ne3 50.c7 Nc4+ 51.Kc5 Nb6= 48.Kd7 Ne5+?! 48...Kb8 49.Kc7 Ka6 50.a4 Ka7 51.c6 Nc4 52.Kd8 Nd6? White has no way to zugzwang Black after 52...Nb6 53.c7 Ka6= 53.c7+– Kb6 54.Kd7 Kc5 55.Bg2 1-0 7.5 Benjamin Bok 2592 Koen Leenhouts 2492 Netherlands tt 2016/17 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Be3 a6 7.Qf3 d6 8.Nxc6 Qxc6 9.Qg3 9.Bd3 Nf6 10.Qg3 9...Nf6 10.Bd3 b5 11.f3² Be7 A) 11...Nh5 12.Qf2 Nf6 is pointless: 13.0-0 Be7 14.a4 b4 15.Na2²; B) 11...Bb7 12.0-0 h5 13.h4! ensures Black’s development remains backward: 13...Nd7 (13...g6?! 14.a4 b4 15.Na2 Qxa4 16.Qf2 Be7 17.Nxb4 Qd7 18.Nxa6±) 14.a4 b4 15.Na2 Qxa4 16.Rfb1! The tactics favour White, e.g. 16...Nc5 17.Nxb4 Qxb4 18.c3 Qb3 19.Ra3 Qb6 20.b4 Nxe4 21.fxe4 Qd8 22.b5±. 12.0-0?! I suppose Bok had not yet read Attacking the Flexible Sicilian, which shows 12.e5 dxe5 13.Ne4! Nh5 14.Qxe5 f5 15.a4! (15.Bc5) 15...bxa4 16.g4 to be effective: 16...Nf6 (16...0-0 17.gxh5 fxe4 18.Bxe4 Bh4+ 19.Kd2 Qd7+ 20.Qd4 Rb8 21.Rxa4 Rxb2 22.Qxd7 Bxd7 23.Rxa6 is a healthy enough extra pawn in the endgame) 17.gxf5 exf5 18.Bc5 Qe6 19.Nd6+ Bxd6 20.Qxe6+ Bxe6 21.Bxd6 Kf7 22.Rxa4² White has the bishop pair for free. 12...0-0 13.a3 e5!= 14.a4 b4 15.Nd5 Nxd5 16.exd5 Qb7 17.a5 17.f4 Qxd5 18.fxe5 Qxe5 19.Qxe5 dxe5 20.Be4 Rb8 21.Ba7 Be6 22.Bxb8 Rxb8= 17...f5 The message is clear – routine play won’t make the cut in the 7.Qf3 Taimanov! 18.Qe1 Bd7 19.Bb6 Qxd5 20.Qxb4 Qf7 21.Qe1 Qh5 22.f4 Bf6 23.Bc4+ Kh8 24.Qd1 Qxd1 25.Raxd1 Rfc8 26.b3 exf4 27.Rxd6 Bb5 28.Bxb5 axb5 29.Rd5 Rxc2 30.Rxf5 Re8 31.R5xf4 Ra2 32.R4f2 Ra3 33.b4 And 1-0 (53). 7.6 Harald Doderer 2467 Peter Krause 2472 Email 2013 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Be3 a6 7.Qf3 Nf6 7...d6 8.Nxc6 bxc6 9.0-0-0 Rb8 10.Qg3 Nf6 8.0-0-0 d6 9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.Qg3 10.g4! 10...Rb8 11.Be2 Be7 11...e5?! 12.f4ƒ 12.h4² 0-0 A) 12...Qb7 13.b3 Qb4 14.Bd2 Qc5 15.h5± Nakar-Warakomska, Warsaw 2016; B) 12...h5 13.b3 e5 14.Bg5ƒ; C) 12...e5 is ATFS’s recommendation, but White keeps an edge with 13.Kb1 Be6 14.Bg5 and now f2-f4 comes with more strength, provoking 14...h6 15.Bc1 h5 16.b3 0-0 17.f4! Bg4 18.Bf3 with attacking chances on the kingside with fxe5/Bg5. 13.h5! Ne8 14.h6 g6 15.Kb1ƒ d5 Now the play resembles our 5...a6 6.Nxc6 line. 15...Bf6 16.Bf4 Qa5 17.Bd2 16.Bf4 Bd6 17.Bxd6 Qxd6 18.Qe3! 18.Qxd6 Nxd6 19.f3² 18...f5 19.f3 Nf6 20.b3 Qe5 21.Qd2 The c8-bishop is perennially passive. 21...Nd7 21...fxe4 22.fxe4 Nxe4? 23.Nxe4 Qxe4 24.Qc3!+– 22.exd5 cxd5 23.Rhe1 Qf6 24.f4± Nb6 25.Qe3 Rf7 25...Rd8 26.Rd4!± 26.Rd4 Qd8 27.Red1 Qd6 28.g4! fxg4 29.Bxg4 White has opened a second front, and Black was unable to hold on for another four years. 29...Qc7 30.Be2 Qe7 31.a4 a5 32.Nb5 Bd7 33.Qe5 Rd8 34.Nd6 Rff8 35.Bg4 Qf6 36.Qe1 Ra8 37.Qc3 Ra7 38.Qc5 Qd8 39.R4d2 Ra6 40.Be2 Ra7 41.Qe3 Rf6 42.Qd4 Bc8 43.Bg4 Qxd6 44.Qxf6 Rf7 45.Qd4 Qc7 46.Qe3 Rf6 47.Re1 Qd6 48.Qc3 Kf7 49.Qxa5 Ke8 50.Rd4 Qc6 51.Rb4 Nd7 52.Rb5 d4 53.Rd5 Qb6 54.Qd2 Nf8 55.Rxd4... 1-0 (68) 7.7 Vishnu Prasanna 2463 Sebastian Bogner 2565 Gibraltar 2015 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Be3 a6 7.Qf3 Bd6 8.0-0-0 Be5 9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.Bd4 Nf6 11.Bxe5 Qxe5 12.Qe3 Ng4 13.Qe1² The best square if Black rejects the silent draw offer 13...Nf6. 13...Qg5+ A) 13...Nf6!? is best, when we should transpose back to 13.Qe2: 14.Bd3 (14.Qe3 Ng4 15.Qe2) 14...d5 15.f3 Rb8 16.Qg3 Qxg3 17.hxg3 h6=; B) 13...0-0 14.f3 Nf6 is also a tough nut to crack: 15.Bd3 (15.g4 d5 16.Qg3 Qxg3!? 17.hxg3 h6 looks solid for Black) 15...d5 16.Qg3 Qxg3 17.hxg3 h6 18.Na4 and White’s position is easier to play, but Black doesn’t experience any problems; C) 13...Qc5?! 14.Rd2 Rb8 (14...0-0 15.h3 Ne5 16.f4 Ng6 17.Qf2 Qxf2 18.Rxf2ƒ) 15.f3 Ne3 (15...Ne5? 16.Qg3! 0-0 17.f4 Nc4 18.Bxc4 Qxc4 19.a3± Avrukh) 16.Qf2!± is an irksome pin. 14.Rd2 Rb8 15.Nd1?! This is way too prophylactic. 15.f3 Nf6 16.g4!? Qc5 17.Qg3 Qb4 18.Nd1 was simple and advantageous. 15...0-0 15...d5 16.f3 Nf6= 16.f3 Ne5 17.Qe3! Qe7 17...Qxe3 18.Nxe3 d5 was better. 18.a3 18.f4 Ng4 19.Qh3 Nf6 20.e5 Nd5 21.Bd3² 18...f6 18...c5!? 19.f4 Nf7 19...Ng4 20.Bd3?! 20.e5! fxe5 21.fxe5 with initiative. 20...d5 21.e5? fxe5 22.fxe5 c5 White has destroyed his own position. However, in the following Black goes too far in his attacking aspirations. 23.c4 Qc7 24.Re1 d4 25.Qh3 Nh6 26.Bb1 a5 27.Nf2 Bd7 28.Qd3 g6 29.Qh3 Kg7 30.g4 Nf7 31.Qh4 Qd8 32.Qg3 Ng5 33.Be4 a4 34.Bg2 Rb3 35.Nd3 Bb5 36.cxb5 c4 37.h4 cxd3 38.hxg5 Qxg5 39.Kd1 Rf4 40.Rf1 Rxg4 41.Qf3 Qxd2+ 42.Kxd2 Rxg2+ 43.Kd1 Black resigned. 7.8 Fabiano Caruana 2716 Sergei Rublevsky 2678 Russia tt 2011 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Be3 Nf6 7.Qf3 a6 8.0-0-0 Bb4 9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.Bd4± Bd6 A) 10...e5? 11.Qg3; B) 10...Be7 11.e5 Nd5 12.Ne4 Black’s dark squares are too weak, as White’s heavy score indicates: 12...c5 (12...0-0 13.Nf6+ Nxf6 14.exf6 Bxf6 15.Bxf6 gxf6 16.Qxf6 Qd8 (Pichot-Grigoryan, Dubai 2017) 17.Qh6 f5 18.g4!±) 13.Nd6+ Bxd6 14.exd6 Qxd6 15.Bxg7 Rg8 16.Bh6 Rb8 17.Bc4 Bb7 18.Qh5!± Rxg2 19.Rhg1! 11.Na4! 11.Bxf6 gxf6 12.Qxf6 Be5 13.Qf3 Rb8° 11...0-0 A) 11...Be7 12.Nb6 Rb8 13.Nc4±; B) 11...Rb8 12.Bb6! Rxb6 13.Nxb6 0-0 14.Kb1± 12.g3? 12.Bxf6 Bf4+ (12...gxf6 13.Qxf6 Be5 14.Qg5+ Kh8 15.Qe7 Kg8 16.g3±) 13.Kb1 gxf6 14.Qg4+ Kh8 15.Qh4 Bg5 16.Qh5 sets White up perfectly for the kingside attack with g2-g3/f2-f4. 12...Be5?! 12...Be7! would be adequate for Black. 13.Bb6 Qb8 14.Qe3!ƒ d5 15.f4 Bc7 16.e5 Nd7 17.Bd4 a5! 18.Qc3 I would rather prepare the c2-c4 break with 18.Kb1!? Ba6 19.Bxa6 Rxa6 20.c4!², like we’ve seen in other games. 18...Bb7 19.Bd3 19.h4!? 19...Rc8 19...Bd8!? 20.Nc5 20.f5 20...Nxc5 21.Bxc5 Ba6= Trading the bad bishop. 22.Rhe1 Bb6 23.Bd6 Bc7 24.Bc5 Bb6 25.Bxa6 Rxa6 26.Ba3 a4 27.Qd3 Ra5 28.f5 Bc5 29.f6 Qb5 30.Bxc5 Qxc5 31.Qd4 Qxd4 32.Rxd4 And White brought home his space advantage in the double-rook ending (1-0, 61). 7.9 Aryan Tari 2532 Sergei Movsesian 2666 Reykjavik 2015 (3) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 Qc7 7.Qf3 d6 8.0-0-0 Nf6 9.Nxc6 Qxc6 10.Be2 Nd7 11.Qg3 b5 12.a3 Bb7 13.Bf4 e5 14.Be3± Rc8 15.Rd2 Building up, but more incisive is 15.f4! Nf6 16.Bf3. 15...Qc7 16.Rhd1 Nf6 17.f3 Qd7 18.Kb1!? 18.Bg5! Qe6 19.Bxf6 Qxf6 20.Qf2!± 18...Qe6 19.Nd5 19.a4!? is not a human move at all, but it looks good. 19...Bxd5 20.exd5 Qd7 21.Qf2! g6 22.g4 22.Bg5! Bg7 23.Qb6± 22...Bg7 23.h4 0-0 24.h5 Rb8 White’s somewhat restrained play has bought Black the time to develop and initiate queenside counterplay. 24...h6 25.Bd3! 25.b3 25.h6 Bh8 25...Rfc8 26.hxg6 fxg6 27.g5 Nh5 28.Bd3 a5! 29.Be4 a4 30.b4 Nf4? 30...Rc3 31.Rd3 Rc4= 31.Rh1 Rc3 32.Rdd1? 32.Qe1! Rbc8 33.Rdh2± 32...Qe7? Both players underestimated the exchange sacrifice 32...Rxa3! 33.Kb2 Rxe3 34.Qxe3 Bf8° when the f4-knight is a strong bastion in Black’s defence. 33.Bd2! Rc4 34.Qh4 Nh5 35.Qg4 Qf7 36.Rh4 Rf8 37.Rdh1 Qe8 38.Rxh5 gxh5 39.Rxh5 Qc8 39...Rxe4 40.fxe4 40.Bxh7+ Kf7 41.Qxc8 41.Qg1! was swifter, but the endgame also looks winning thanks to the darting bishops. 41...Rcxc8 42.Bd3 Rh8 43.g6+ Ke7 44.Bg5+ Bf6 45.Bxf6+ Kxf6 46.Rf5+ Kxg6 47.Rxe5+ Kf7 48.Rf5+ 48.Re6 48...Ke7 49.Bxb5 Rh2 50.Bc6+–... 1-0 (60) 7.10 Ivan Popov 2622 Vladimir Lazarev 2387 Chennai 2015 (4) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Qc7 5.Nc3 e6 6.Be3 a6 7.Qf3 Nf6 8.0-0-0 Be7 9.Kb1 d6 10.Nxc6 bxc6 11.g4 Rb8 12.g5 Nd7 13.Qg3± It somehow looks as though White has played several more moves than Black! 13...Qa5 13...0-0 14.h4 Qa5 15.Bc1± 14.Bc1 d5 15.h4 Qb4 16.h5 The pawn storm can pay dividends even before Black has castled. 16...Bd6 16...0-0 17.b3!? 17.f4 Nc5 18.Qe3 0-0 19.e5?! 19.h6 g6 20.a3 Qxa3 21.exd5 cxd5 22.Nxd5! would have been merciless. 19...Be7 20.Rh3 20.Bh3!? 20...Na4? 20...a5± 21.Nxa4 Qxa4 22.g6 22.Qg3 22...h6 22...fxg6 23.hxg6 h6 at least keeps the pieces out. 23.gxf7+ Rxf7 24.Bd3+– c5 25.Bg6 Rf8 26.Rg1 Rb7 27.Rhg3 Bh4 28.Rg4 d4 29.Qd2 Bd8 30.Be4 Rff7 31.f5 exf5 32.Rxg7+ Rxg7 33.Bd5+ Kf8 34.Qxh6 1-0 7.11 Maxim Lugovskoy 2431 Rinat Jumabayev 2600 Riga 2015 (3) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 e6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Be3 a6 7.Qf3 Nf6 8.0-0-0 Be7 9.Kb1 0-0 10.g4 Nxd4 11.Bxd4 b5 12.Bd3 12.g5! Ne8 13.Qh5 sets up Rd3-h3 to good effect. 12...Bb7 13.Qh3 13.g5!? Ne8 14.Rhg1 13...e5? 13...g6! 14.e5 Nd5² 14.g5! A striking reply, ignoring Black’s threat! For if now 14...exd4 15.gxf6 Bxf6 16.e5+–. 14...Ne8 15.Be3± Nd6 15...Rc8 was the last shot at survival, practically speaking. 16.f4! f6?! 17.g6 17.Rhg1! fxg5 18.fxe5+– 17...hxg6 18.Rhg1 b4 19.Rxg6!+– bxc3 20.Rxg7+ Kxg7 21.Qh5 White had a forced mate with 21.Qg4+ Kf7 22.Qh5+ Ke6 23.Bc4+ Qxc4 24.f5+ Nxf5 25.exf5#. 21...Rg8 22.fxe5 Nf7 23.Rg1+ Kf8 24.Bh6+ Nxh6 25.Qxh6+ Kf7 26.Qh7+ Ke6 27.Rxg8 Qxe5 28.Rxa8 Bxa8 29.Qg8+ Kd6 30.Qxa8 a5 31.Qa6+ Kc7 32.Bb5 Qd4 33.Qxa5+ Kb8 34.bxc3... 1-0 (46) 7.12 Alexandr Fier 2581 Koen Leenhouts 2487 Amsterdam 2017 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Be3 a6 7.Qf3 Nf6 8.0-0-0 Ne5 9.Qg3 b5 10.f4 Neg4 11.Bg1 h5 11...b4 12.Na4 h5 13.e5 12.e5 b4 13.Na4 Nd5 14.h3 Nh6 15.Bd3² g6 15...Bb7 16.Be4 Rc8 17.Kb1 g6 18.Qf3 transposes to 17...Rc8. 16.Be4 Bb7 17.Qf3 Nf5? This allows a strong exchange sacrifice. 17...Rc8 18.Kb1 Nf5 19.Bf2 Nxd4 (19...Be7 20.Nb3!) 20.Rxd4 Bc6 21.Rc4 is the main line in ATFS, where they show the engine initially underestimates White’s space advantage and development: 21...Qa5!? (21...Qb8 22.b3 Be7!? is another try, but 23.Rd1 h4 24.Bd4² makes it hard for Black to free himself) 22.b3 Be7 23.Bd4 Rd8 24.Nb2² White is ready for either g2-g4 or Nd1-e3. 18.Nxf5! gxf5 19.Bxd5 Bxd5 20.Rxd5 exd5 21.Nb6 Rb8 22.Nxd5 Qc6 23.Bf2!± Practically, Black’s scattered position is nearly indefensible. 23...Be7 24.Rd1 a5 24...Rc8 25.Rd2 25.Qd3 a4?! 25...Rb7 26.b3± 26.Nxe7 Kxe7 27.Qxf5 b3 28.axb3 axb3 29.Rxd7+! And Black resigned. Chapter 8 The Paulsen 5.Nc3 without 5...Qc7 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3!? This move is not as fashionable as 5.Bd3 (recommended by Negi in GM Repertoire) or 5.c4 (the repertoire in Attacking the Flexible Sicilian), but I have found that 5.Nc3 also gives good chances for an advantage, and in my experience, is easier for amateur players to grasp than the Hedgehog structures. Rare fifth moves A) 5...Nc6 transposes to the previous chapter, the one on the Taimanov; B) 5...Bc5?! is the main reply to 5.Bd3, but doesn’t make sense here: 6.Nb3 Be7 7.Qg4 g6 8.Qg3 with an edge for White; C) 5...Ne7 6.Be3 Nbc6 7.Nb3!² leaves the e7-knight misplaced by avoiding ...Nxd4/Nc6, as we saw last chapter; D) 5...d6!? is slightly annoying, as it’s not easy to stay in our Scheveningen repertoire. But as we will see, even without ...Nf6 inserted, the Keres Attack has some bite! 6.g4!? (6.Be3 isn’t an automatic transposition because of 6...b5!?) D1) 6...h6 7.Bg2 will transpose to the 6.h3 Najdorf if Black plays ...Nf6. Otherwise, 7...Ne7 8.Be3 Nbc6 9.f4 Nxd4 10.Qxd4 Nc6 11.Qd2 Qh4+ 12.Qf2 Qxf2+ 13.Kxf2 gives White a tiny edge in the endgame, due to his space advantage; D2) 6...Ne7 7.Be3 Nbc6 8.Nb3! (avoiding ...Nxd4/Nc6) 8...b5 9.f4 in turn favours White, who has been permitted a very aggressive set-up. See the model game Ter Sahakyan-Grachev, Plovdiv 2012; D3) 6...b5 7.Bg2 Bb7 8.0-0 Ne7! This is a better set-up against the g2-g4 plan, though White also benefits from not needing to play h2-h3, compared to the 6.h3 Najdorf: 9.f4 Nbc6 (9...Nd7!? is flexible but a bit passive after 10.Be3 Rc8 11.a3²) 10.Be3 Nxd4 11.Qxd4 Nc6 12.Qd2 Be7 Black has successfully coordinated his minor pieces, but remains slightly worse after 13.Ne2!N 13...0-0 14.c3 as he lacks an active plan, while White’s kingside expansion flows like a river (14.g5 is even more incisive). 5...b5 This is the main alternative to the 5...Qc7 of the next chapter, but it has come under pressure of late. 6.Bd3 Here we have reached another crossroads. Alternatives to 6...Qb6 A) 6...Qc7 transposes to 5...Qc7; B) 6...Ne7!? 7.0-0 Nec6 looks strange, but calls for precise play to exploit: 8.Nxc6 Nxc6 9.Be3 Bb7 (otherwise a4-a5! proves unpleasant) 10.f4 Be7 11.a3 0-0 (11...d5 12.exd5 exd5 13.Bf2² gives White the better structure; 11...d6 12.Qh5! 0-0 13.Rad1 Re8 14.Qh3!? g6 15.f5! is a model demonstration of how to execute White’s attack) 12.Qg4!?² (or 12.Qh5²) White’s extra kingside space gives him chances for a successful attack; C) 6...Bc5 makes more sense with our bishop on d3, but is still flawed: 7.Nb3 Be7 (7...Ba7 8.Qg4 Nf6 9.Qxg7!N 9...Rg8 10.Qh6 Bxf2+ 11.Ke2! refutes Black’s concept, e.g. 11...Bb6 12.e5 Rxg2+ 13.Ke1 Ng8 14.Qxh7 with a huge initiative) 8.0-0 Nc6 (8...Bb7 and 8...Qc7 will transpose to other lines; 8...d6?! is the most common move, but allows the tactic 9.e5!N 9...dxe5 10.Qf3 Ra7 11.Be3 Rd7 12.Nc5 Rc7 13.b4 Nf6 14.a4 bxa4 15.Rfd1 Nbd7 16.N3xa4 and White has an obvious initiative for the pawn) 9.f4 d6 10.Qf3 Bb7 11.e5N 11...d5 White has an amazing version of the Steinitz French, and might clamp down on d4 with 12.a4 b4 13.Ne2 Nh6 14.Be3±; D) 6...d6 7.0-0 Nf6 This is too slow because of the undermining a2-a4 plan: 8.a4! (8.b4!? also looks good for White, but we don’t have to fear ...b5-b4) 8...b4 9.Na2 and now: D1) 9...Qb6 10.Be3 Qb7 11.c3 bxc3 12.Nxc3 Nbd7 13.Rb1ƒ and b2-b4 will secure a clear positional advantage on the queenside; D2) 9...Bb7 10.Re1 Be7 (10...d5 11.e5 Ne4 12.c3 bxc3 13.Nxc3 gives White a strong initiative because of his significant lead in development) 11.Nxb4 d5 12.e5 Bxb4 13.c3 Be7 14.exf6 Bxf6 15.Qb3 White had a huge attack in Vallejo Pons-Van Wely, Monaco 2006; D3) 9...e5 10.Nf3 Nc6 11.Bd2 D31) Now an emphatic line runs 11...Rb8 12.c3 bxc3 13.Bxc3 a5. This ambitious break offers the best chances to mix up the game, though he lacks the development to handle White’s aggression. 14.b4! (anyway!) 14...axb4 15.Bb5 Bd7 16.Nxb4 Nxb4 17.Bxb4 Bxb5 18.axb5± Taking on b5 is suicidal, but otherwise White is clearly commanding the play; D32) 11...Qb6 12.Qe1 Rb8 13.c3 bxc3 In Landa-Vachier-Lagrave, Paris 2004, White had the chance for 14.bxc3! Be7 15.Nb4 0-0 16.Qe2² with persistent piece activity; D33) 11...d5!? 12.exd5 Qxd5 13.Qe1 Bg4 14.Ng5 a5 15.b3!ƒ Bc4/Bb5 will give White a tangible initiative; The old main line 6...Bb7 7.0-0 A) Most rare moves are well met by e4-e5, e.g. 7...Be7 8.e5!?²; B) 7...Nf6 usually needs to be prepared by defending against e4-e5. 8.e5 Nd5 9.Nxd5 Bxd5 10.Qg4! Qc7 11.Re1 transposes to 5...Qc7 lines; C) 7...b4 is too early: 8.Na4 Nc6 9.Nb3! Nf6 10.Be3 d6 11.f4 Be7 12.Qe2 0-0 13.Rad1² and White is better on both flanks; D) After 7...Bc5 8.Nb3 Be7 (8...Ba7 is thematically met by 9.Qg4!±) 9.e5! Black can’t properly develop his kingside: 9...Nc6 (9...f5 can be met as in Petr-Fedorov, Czechia tt 2013) 10.Re1 Qc7 11.Bf4! g5 12.Bg3 h5 13.h3 g4 14.hxg4 h4 15.Bf4 h3 16.Be4 and Black’s blatant attack had led nowhere in Kobryn-Andre, email 2013; E) 7...Qb6 is a worse version of 6...Qb6 as we don’t have to retreat our knight: 8.Be3!? Bc5 9.Nce2 Nc6 10.c3 Nf6 11.b4! White has a strong initiative, e.g. 11...Bxd4 12.Nxd4 Qc7 13.Nxc6 Bxc6 14.Re1! Nxe4 15.a4 Nxc3 16.Qg4 Nxa4 17.Bf4! Qb7 18.Bd6! and Black’s weak dark squares make his position unplayable; F) 7...Ne7 is a slightly unusual development – we can anticipate ...Nc6 with 8.Nb3!? Ng6 9.Be3 Be7 10.f4 Nc6 11.Qh5 0-0 12.Rf3!±, when Rh3 gives White a nearly winning attack; G) 7...d6 8.a4 b4 9.Na2 is going to transpose to 6...d6 after 9...Nf6, as the independent 9...d5 10.e5 Nc6 11.Nxc6 Bxc6 12.Bd2 Qb6 13.b3 leaves Black behind in development with the worse structure; H) 7...Qc7 transposes to 5...Qc7; I) 7...Nc6 used to be a Kamsky favourite before a couple of reversals – Black is certainly taking some risk by delaying his kingside development: 8.Nxc6 Bxc6 (8...dxc6 makes less sense with the bishop on b7: 9.e5 Ne7 10.Bg5! Qc7 11.Re1 Ng6 12.Qh5ƒ and Black hasn’t achieved ...c5-c4 in time) 9.Re1 Black has some flexibility with his set-up, but I don’t share Castellanos’s recent view that Black can maintain equality. I1) 9...b4 10.Nd5! is a trick we’ll keep seeing; I2) 9...Nf6 10.e5 b4 11.exf6N 11...bxc3 12.fxg7 Bxg7 13.b3 leaves Black without a safe position for his king, as evidenced by 13...0-0 14.Qh5 f5 15.Bf4ƒ and a Re3 rook lift; I3) 9...Ne7 proved tricky in a couple of correspondence games: 10.Be3 b4 (10...Ng6 11.a4 Bb4 12.axb5 axb5 was Fritsche-Tosi, email 2010. Rather than cashing in on b5, it’s also possible to maintain the pressure with 13.Qe2!? Bxc3 14.bxc3²) 11.Ne2 Ng6 White successfully played on the queenside in Volkov-Khromov, email 2013, but I prefer kingside play with 12.f4! Be7 13.Nd4 Bb7 14.Qh5 0-0 15.f5 when Black should already sacrifice a pawn, but 15...Ne5 16.fxe6 Bf6 17.exf7+ Rxf7 18.Rad1 doesn’t qualify as full compensation; I4) 9...Qb8 10.a4 b4 11.Nd5! From here, the knight limits Black’s options for development. 11...Bd6 (11...Nf6? 12.Bf4 Bd6 13.Bxd6 Qxd6 14.Nb6 Rd8 15.e5±) 12.Qh5 We need one more branch of variations to address how White can use his initiative: I41) 12...h6 is a slow move that can be met with 13.a5!?N 13...Bxd5 14.exd5 Nf6 15.Qf3 Bxh2+ 16.Kf1! Bd6 17.dxe6 dxe6 18.Ra4 Ke7 19.Be3 with a strong initiative for the pawn; I42) 12...a5!?N is a more useful waiting move: 13.Bd2 Be5 (13...h6 14.c3 Bxd5 15.exd5 Nf6 16.Qh4 Nxd5 – we don’t mind Black taking our pawns, as that also opens lines to their king! 17.Be4 bxc3 18.bxc3 Qb3 19.Rad1 Qxa4 20.Qh3 Kf8 21.Qf3ƒ made it hard for Black to complete development in Kuhne-Mendieta Aibar, email 2010) 14.c3 Nf6 15.Nxf6+ gxf6!? (Black is trying to hold the centre together, but it comes at a price. Otherwise, 15...Bxf6 16.cxb4 axb4 17.e5ƒ) 16.Red1 bxc3 17.bxc3 Rg8 18.g3² It’s not easy for Black to coordinate his rooks; I43) 12...Be5 13.Ne3 Nf6 14.Qh4 h5 15.Nc4! is a protracted but worthwhile manoeuvre! For example, 15...Ng4 16.Nxe5 Qxe5 17.f3 Qd4+ 18.Kf1 Ne5 19.Be2 f6 20.Qf2 Qxf2+ 21.Kxf2 and White has the trademark bishop pair advantage; I44) 12...Bxd5 13.exd5 Nf6 14.Qg5 0-0 15.Qh4! Be5 can be met in several ways, but simplest is 16.dxe6 fxe6 17.Rb1²; I45) 12...Kf8 looks strange, but does threaten our knight. I like the pawn sacrifice 13.e5N 13...Bxd5 14.exd6 Qxd6 15.a5 Ne7 16.Bd2 when White has greater piece harmony; I46) 12...Ne7 13.Nxe7 Bxe7 14.e5!N (it is important to stop Black castling, unlike the 14.b3 0-0! 15.Bb2 f6= of Külaots-Kamsky, Stockholm 2017) 14...g6 (or 14...a5 15.Qg4 Kf8 16.Bg5 Bxg5 17.Qxg5²) 15.Qh6 Bf8 16.Qf4 Bg7 17.Qg3 0-0 18.h4!² White’s kingside play has good chances of success, due to his extra space in the centre. I5) 9...Bc5 10.Qh5 (White must play directly, or Black will have a very harmonious position with ...Ne7-g6) 10...d6 (too slow is 10...Bd4 11.Ne2 g6 12.Qh3 Bg7 (Areshchenko-Pantsulaia, Dubai 2017) 13.c3²; 10...Qb6 11.Be3 Bxe3 12.Rxe3 Ne7 13.Nd5! Qd8 14.Nxe7 Qxe7 15.e5 h6 16.Rg3 g6 17.Qe2ƒ retained considerable pressure in Delgado Ramirez-Kamsky, Tromsø 2014: 17...Qc5 18.Re1 h5 19.h3 a5 20.Qd2! b4 21.Qf4 and Rc1/c4 or Be4 is a promising follow-up for White) 11.e5 White has strong pressure here, as we’ll see in Pijpers-Neverov, Ortisei 2016. The modern trend 6...Qb6!? This has emerged as the main line, with the idea of forcing White’s knight back before placing the queen on the natural c7-square. 7.Nf3! The correct retreat, to support the e4-e5 break. Alternatives to 7...Qc7 A) 7...Bc5?! doesn’t make sense as White wanted to castle anyway: 8.0-0 Bb7 9.a4! b4 10.a5 Qc7 11.Na4 We can see that Black should have played ...Qc7 earlier to avoid this queenside clamp, as 11...Qxa5 12.Nd2! Be7 13.Nc4 Qc7 14.Nab6 Ra7 15.e5 would present a decisive bind for the pawn; B) 7...d6 8.a4 b4 9.a5 is another example of the same principle: 9...Qb7 (9...Qc7 10.Na4 Nd7 11.Be3 Rb8 12.Nb6 was the dream bind in Gritskov-Perun, Kiev 2002) 10.Na4 Nd7 11.0-0 Ngf6 12.Qe2 Be7 At least White doesn’t have Be3/Nb6, but no less powerful is 13.e5! Nd5 14.c4 bxc3 15.exd6 Bxd6 16.bxc3 and c3-c4, with a strong initiative; C) 7...Nc6 8.0-0 (8.Bf4!? is almost untried, but looks good for White after 8...d6 9.a4 b4 10.a5!N 10...Nxa5 11.Na4 Qc7 12.0-0 (or 12.c4!?) 12...Nc6 13.c4 bxc3 14.Nxc3 Nf6 15.Bb5! with pressure resembling a turbo-charged Morra Gambit) and now: C1) We already know the theme 8...Nf6? 9.e5±; C2) 8...Be7 9.a4 b4 10.a5!N 10...Qc7 11.Na4 Nxa5 12.e5!?ƒ with a strong bind is hardly a new motif for us either. A direct confrontation favours the better developed player; C3) Also in the event of 8...d6 9.a4 b4 10.a5! Nxa5 11.Na4 Qc7 12.Be3 Rb8 13.Nb6! Rxb6 14.Rxa5 Rb8 15.Qa1 White regains his pawn with interest, Felgaer-Hellsten, Santiago 2005; C4) 8...Nge7 was Kamsky’s preference, but without much success: 9.Re1 Ng6 10.Nd5! Qd8 (White’s last was a sham sacrifice: 10...exd5 11.exd5+ Nce7 12.Bxg6 hxg6 13.d6+–) 11.a4 Rb8 12.axb5 axb5 In Xu-Khurtsidze, Hyderabad 2002, White could have continued as in a Morra with 13.Bg5!? f6 14.Be3± as accepting the knight sacrifice would be suicidal; C5) 8...Qb8 (the queen is placed less naturally here than on c7) 9.Re1 As usual in the Kan, Black has a (not very appealing) choice, requiring a final branch: C51) 9...Bb7 allows for a central strategy: 10.e5 Nge7 11.Qe2N 11...Nb4 12.Be4 Nbd5 13.Nxd5 Nxd5 14.c3²; C52) 9...d6 10.Bf4! Nge7 11.e5 d5 12.Qd2 Bb7 was Abergel-Primel, Sautron 2005, where 13.h4! would complicate Black’s kingside development; C53) 9...Nge7 allows 10.a4 b4 11.Nd5!N when taking the knight is risky: 11...d6 (after 11...exd5 12.exd5 Nd8 13.Ne5! d6 14.Nc4 White’s attack plays itself, as Black can hardly develop) 12.Ne3 Ng6 13.Nc4± It is not easy for Black to cover the weak b6-square against Be3/a4-a5; C54) 9...Bd6 10.e5! and now: C541) 10...Nxe5 is too risky without proper development: 11.Nxe5 Bxe5 12.Rxe5! Qxe5 13.Qf3 d5 14.Bf4 Qf6 15.Qg3 h5 16.Nxd5!? (16.Be5ƒ is the slower approach) 16...exd5 17.Re1+ Ne7 18.Bg5 h4 19.Qe3 Qe6 20.Qd2 f6 21.Rxe6 Bxe6 22.Be3 and the material imbalance is in White’s favour, as Black is not in time to coordinate his rooks to defend his weaknesses; C542) 10...Bc7 11.Bf4 Nge7 12.Bg3 Ng6 13.Qe2 Bb7 (13...0-0 14.Rad1 h6 15.h4ƒ puts Black’s king under fire) 14.Rad1 Nce7 15.Ne4! Grischuk placed the bishop here against Svidler, but with our extra space, we should keep the pieces on a bit longer. 15...Nf5?! 16.Nc5 Nxg3 17.hxg3 Bc6 18.Be4± Black could no longer defend the weak d7 point in SchakelWukits, email 2012. 7...Qc7 8.0-0 Bb7 Black should keep his pawn on d7 to nullify queenside plans with a2-a4 and keep the centre closed. A) 8...d6?! 9.a4 b4 10.Na2 Nc6 11.Bd2 Qb7 12.Qe1 Rb8 13.c3 bxc3 14.Bxc3 Nf6 15.b4 Be7 16.b5 axb5 17.axb5 Na7 18.e5! was a model execution of White’s plan in Najer-Kamsky, Khanty-Mansiysk 2013; B) 8...Nc6 9.Re1 d6?! The queenside plan is slightly less effective (though still good) with ...Nc6 already played, but best of all is 10.Bf4! Ne5 11.Nd5!N when Black can hardly accept the sacrifice: 11...Nxf3+ 12.Qxf3 exd5 13.exd5+ Be7 (or 13...Kd8 14.a4) 14.Qg3! Kf8 15.Rxe7 Nxe7 16.Bxd6 Qd8 17.Re1 Ra7 18.Bc5 Rd7 19.Qe3 and Bf5, after which Black’s destruction resembles a Morphy game. 9.Re1 Be7 The flexible move. One feels that White’s position is more harmonious, though proving the advantage requires an excellent understanding. A) 9...Ne7? 10.Bxb5! shows Black’s difficulty bringing out his kingside pieces; B) 9...Nf6 10.e5 Nd5 11.Nxd5 Bxd5 12.a4 b4 13.Ng5! Nc6 14.Bf4± and Qh5 is another case in point; C) 9...b4 10.Na4 Nf6 11.Be3!± with Nb6/Bb6 shows the problem with the early ...b5-b4; D) 9...d6 10.a4 b4 11.Na2 and Bd2/c2-c3 is much better for White. Meanwhile, 11...Nf6 12.Nxb4 d5 13.e5 Bxb4 14.exf6 gxf6 15.c3 Bd6 16.Bh6 leaves Black’s king without refuge; E) 9...Bc5 can be met by the clever 10.Qd2!² with the idea of 11.b4!, as demonstrated in Voiculescu-Schiendorfer, email 2012; F) 9...Nc6!? is rare but tough to prove an edge against: F1) 10.Bg5 is another route to a tiny edge: 10...h6 11.Bh4 Bd6!? (11...d6 12.Qd2² prepares a strong a2-a4) 12.Bg3! Bxg3 13.hxg3 Nge7 14.e5 0-0 15.Qd2 Ng6 16.Qe2 and White’s position is easier to play with his space advantage, though objectively Black should be fine; F2) 10.e5 Nge7 Black gets a surprising amount of compensation if we play the familiar 11.Bxb5, so I favour 11.Bg5!?: F21) A typical continuation is 11...h6 12.Bd2 b4 13.Na4 Nd5 14.Be4 Na5 15.a3 Nc4 16.Bxb4 Nxb4 17.axb4 Bxb4 18.Bxb7 Qxb7 19.c3 Be7 20.Qd3 when Black’s queenside pawns come under fire; F22) 11...Ng6!? 12.Bxg6 hxg6 is a solid option, however: 13.a4 b4 (after 13...bxa4 14.Ne4! a3 15.bxa3 Na5 16.Qd3 I prefer White’s chances because of Black’s difficulty completing development) 14.Ne4 Rc8 (14...Nxe5 15.Nxe5 Qxe5 16.Nf6+ gxf6 17.Rxe5 fxe5 – the engines often misevaluate these queen vs. pieces positions, but here White is really better after 18.Qe1! e4 19.Qe3 due to Black’s disconnected rooks) 15.Rc1 Na5 16.b3 Bc5 17.Qd3 Bxe4 18.Rxe4 Qb6 19.Re2 d5 20.exd6 Qxd6 21.Qe4 0-0 22.Rd2 Qc6 23.Qh4 f6 24.Rcd1! White is just in time to take the d-file and maintain a small edge; F23) 11...Rc8 I tried just about every move here for White. I like the direct continuation 12.Ne4!?N, as Black’s position has more scope to improve after quiet play: 12...Ng6 13.Nd6+ Bxd6 14.exd6 Qxd6 15.Bxg6 Qxd1 16.Bxf7+ Kxf7 17.Raxd1 Ke8 18.c3 Objectively, Black can gradually equalise, but for the time being White has the slightly better structure and coordination. Back to the position after 9...Be7. 10.e5! Killing the g8-knight. 10...f5 11.Nd4! 11.Nh4 g6 12.Nf3 Nc6 13.a4 b4 14.Nb1= is the main line, but Black has been successful in practice. 11...g6 This is necessary as 12.Nxf5 was a threat. 12.Bf1 Nc6 13.Nxc6 Bxc6 14.Be3 h5! Preparing 15...Nh6 and a kingside pawn storm. This is a critical line as Black has held his own in correspondence, but I have improvements ready. 14...Bf8 15.Qd2 Kf7 16.Rad1 Ne7 17.Bh6 Rd8 18.Bxf8 Rhxf8 19.Qg5ƒ was the model game Shields-Zaas, email 2012 – Black should not allow the exchange of dark-squared bishops with his pawns entirely on light squares. 15.a4 b4 16.Ne2 White is better, but if he wastes time, Black can make use of his healthy pawn structure. See Schakel-Leal, email 2013. Summary 2...e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3: 5...d6 +0.30 5...b5 6.Bd3: 6...d6 – +0.50 6...Bb7 – +0.35 6...Qb6 7.Nf3 Qc7 8.0-0 Bb7 9.Re1: 9...Bc5 – +0.35 9...Nc6 – +0.25 9...Be7 – +0.45 8.1 Samvel Ter Sahakyan 2578 Boris Grachev 2705 Plovdiv 2012 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 4...a6 5.Nc3 d6 6.g4 Ne7 7.Be3 Nbc6 8.Nb3 b5 9.f4 5.Nc3 d6 6.g4 6.Be3 Nf6 7.Qe2 is my repertoire recommendation. 6...Nge7 7.Nb3 a6 8.Be3 b5 9.f4² Bb7 Too speculative is 9...g5?! 10.fxg5 Ne5 11.Qe2 Bd7 12.a3 Nc4 13.0-0-0ƒ. 10.Qe2! Na5 11.0-0-0 Nc4 11...b4? 12.Na4 Nxb3+ 13.axb3 Bxe4? 14.Bb6+– 12.Bf2 12.Kb1! Rc8 (12...Nxe3?! 13.Qxe3 Nc6 14.g5) 13.f5 Qc7 14.Bc1 Na3+ 15.bxa3 Qxc3 16.Bg2 left White ahead in force in Zemlyanov-Vecek, email 2014. 12...Qc7 The game is quite scrappy, but I’ve included it to demonstrate that the repertoire ethos of attacking on the kingside throws up significant winning chances for both sides. 12...Rc8!? 13.Nc5 Bc6 14.f5!ƒ 13.a4 Creative, but I would play 13.Qf3!?ƒ to chop off the c4-knight. 13...Bc6 13...b4! 14.Qxc4 Qxc4 15.Bxc4 bxc3 16.Rhe1 cxb2+ 17.Kxb2 Nc6= 14.Nd4 14.f5! 14...Bd7 15.h4 15.Qd3!? Ng6 16.Bg3 Qc5= 15...Ng6! 16.Qf3 b4? Black starts to reject simple, good moves, probably in fear of White’s h4-h5, booting the knight. After 16...bxa4! 17.h5 Ne7 Black has excellent queenside play. 17.Na2 Be7? 17...a5 18.Bxc4 Qxc4 19.b3 Qc7 20.Nb5 Bxb5 21.axb5² 18.h5 18.Nxb4 a5 19.Na2± 18...Nxf4 19.Qxf4 e5 20.Qg3 exd4 21.Bxd4? The d4-pawn was going nowhere, but b4 was a healthy pawn – so it should be taken first. 21.Bxc4 Qxc4 22.b3 Qe2 23.Nxb4± 21...Bg5+? 21...a5! 22.Kb1 0-0 23.h6 Kortchnoi would have snapped the pawn off with 23.Nxb4!, and rightly so. 23...Rfc8 24.Rh2 a5 25.Bxc4 25.hxg7 25...Qxc4 26.hxg7 f6 26...Bc6!? 27.b3 Qe6 28.Rxh7 f6! 29.Rh8+ Kf7 with counterplay. 27.Nc1 h6? 27...Qe6! crucially threatens ...Bxa4. 28.b3 28.Be3! 28...Qe6 29.Qd3 29.Re1!± 29...Bc6 30.Re1 Re8 31.Rhe2 Bh4 32.Qd2? White makes a bluff that gets handsomely rewarded. 32.Rh1 Bg5 33.Rhe1= 32...Kxg7 32...Bxe4! 33.Rxe4 (33.Qxh6 Bxe1 34.Qh8+ Kf7–+) 33...Bxe1 is a cute X-ray motif. Or 32...Bxe1 33.Rxe1 Bxe4 34.Qxh6? Bxc2+ 35.Kxc2 Qxe1 36.Qh8+ Kf7–+. 33.Nd3 Bg5? 33...Bxe1 34.Rxe1 Bxe4 35.Qf4° 34.Nf4± Qf7 35.Be3 35.Rf1! Rxe4 36.Nh5+ Qxh5 37.Bxf6+ Kh7 38.gxh5 Bxd2 39.Rxd2+– 35...Bxe4 36.Ka1 Bg6? 36...Kg8! anticipates Nh5, but both players may have already been in time trouble for some moves. 37.Nxg6 Kxg6 38.Bxg5 Rxe2?! 38...hxg5 39.Rh2! Rxe1+ 40.Qxe1+– 39.Qxe2+– Qd5 39...hxg5 40.Qe4+ 40.Bc1 Qe5+ 41.Kb1 Qxe2 42.Rxe2 1-0 8.2 Aleksandr Volkov 2298 Dmitry Khromov ICCF email 2013 1.e4 c5 2.Nc3 e6 3.Nf3 a6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 b5 6.Bd3 Bb7 7.0-0 Nc6 8.Nxc6 Bxc6 9.Re1 Ne7 10.Be3 b4 11.Ne2 Ng6 12.Nd4 12.f4! 12...Bb7 13.c4!? 13.Nb3 13...Be7 14.c5 This ambitious plan is rewarded in the game, though it doesn’t seem to give an advantage if Black is quick to liquidate the cramping c-pawn. 14...0-0 15.Rc1 a5?! 15...Qb8! prepares ...Rc8/...d7-d6 before White can tighten his clutch: 16.Bb1 (16.c6 dxc6 17.Nxc6 Bxc6 18.Rxc6 Ne5 19.Rb6 Qc8=) 16...Rc8 17.Nf3 d6 18.cxd6 Rxc1 19.Qxc1 Bxd6= 16.Nb5 Qb8 17.a4 bxa3 18.bxa3² Bc6 18...Rc8 19.a4ƒ 19.a4 White’s space advantage is particularly unpleasant on a board full of pieces, and Black starts to drift. 19...Nf4 20.Bf1 Ng6 21.f3 Bh4 22.Re2 f5 23.exf5 exf5? 23...Rxf5 24.Nd4 Rd5 25.Nxc6 Rxd1 26.Nxb8 Rxc1 27.Bxc1 Rxb8 28.Rb2 Rxb2 29.Bxb2² 24.Nd4 24.Nd6!+– sets the octopus knight free to wreak havoc. 24...Kh8 25.Kh1 Ne7 26.g3 Bf6 27.Nxc6 dxc6 28.Bf4 Qb4 29.Bd6 Rfe8 30.Rb1 Qa3 31.Qc2 Qxf3+ 32.Bg2 Qh5 33.Rbe1 Rad8 34.Re6 Ng8 35.Bxc6 Rxe6 36.Rxe6 f4 37.Kg2 Rc8 38.Bb7 Rd8 39.Bf3 Qf7 40.Qf5 fxg3 41.hxg3 g6 42.Qe4 Rc8 43.c6 Bg7 44.c7 Nf6 45.Qe2 Ne8 46.Re7 1-0 8.3 Arthur Pijpers 2471 Valeriy Neverov 2507 Ortisei 2016 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3 b5 6.Bd3 Bb7 7.0-0 Nc6 8.Nxc6 Bxc6 9.Re1 Bc5 10.Qh5 d6 11.e5 dxe5?! A) 11...g6 12.Qe2 dxe5 13.a4! b4 14.Ne4 Be7 15.Bxa6 Qa5 16.Bd3 Nf6 17.Nxf6+ Bxf6 18.Bh6!± kept Black’s king in the centre in Preusse-Melde, email 2011; B) 11...Qb6 12.Be3 Bxe3 13.Rxe3 Qc5 14.Qg4!ƒ; C) 11...d5?! 12.Qg4 g6 13.Ne2 Qb6 14.Qf4 and Black’s kingside structure was swiss cheese in Bok-Drozdowski, Groningen 2012; D) 11...Bd4 12.Bg5 Qb6 13.Ne4 (13.Be3N 13...dxe5 14.Bxd4 Qxd4 15.Rxe5 Kf8 16.Rd1 Nf6 17.Qg5!? h6 18.Qg3 Qb6 19.Ree1 Kg8=) 13...Bxe4 14.Rxe4 d5 15.Rf4 Ra7 In correspondence White gave up the e5-pawn, but I want to preserve the space advantage for our attack: 16.Qe2!N 16...Bxb2 17.Rb1 h6 (17...Bc3 18.Ra4!, threatening 19.Bxb5, is quite beautiful! 18...f5 19.exf6 Nxf6 20.Bxb5+ Ke7 21.Qe3²) 18.Bxh6 Rxh6 19.Rxb2 Ne7 20.g3 Qa5 (20...Kf8 21.a4 Nc6 22.c4!ƒ rips the game open) 21.Qe3 Nc6 22.Rg4 and Black has trouble covering all the entry points. 12.Rxe5 Nf6 13.Rxe6+ Be7 14.Qc5 fxe6 15.Qxc6+ Kf7 16.Qf3! Anyone from the Dutch School of Chess would be thrilled with such a strong attack for so little material! 16...h6 A) 16...Re8 17.a4 Kg8 scurries the king away for a pawn; B) 16...Rf8 17.Bxh7! g6 18.Bh6 Rh8 19.Rd1 Qe8 20.Ne4 Rxh7 21.Bg5± 17.Bf4 17.Qg3! exploits the drawback of ...h7-h6. 17...Bd6 The rest of the game is quite turbulent, showing that material imbalances aren’t easy to handle, even for strong players. 18.Ne2 White begins to play too passively. 18.Bxd6 Qxd6 19.a4 bxa4 20.Ne4!± 18...g5?! 18...Re8= 19.Bg3 19.Bd2!? 19...Qb6 20.Bxd6 Qxd6 21.Rd1 21.a4! 21...Rad8? Better was 21...Kg7 22.c3ƒ. 22.Bg6+ Kxg6 23.Rxd6 Rxd6 24.h4? 24.h3!± White’s material advantage permits him to slowly improve the position. 24...Rhd8?! 24...Rd1+ 25.Kh2 Rhd8 was better. 25.g3 Rd2 26.Qe3 26.Nc3! defends the pawn indirectly, as after 26...Rxc2? 27.Ne4 all Black’s defences fail tactically. 26...e5! 27.Nc3 gxh4 28.Ne4!? Rd1+ 29.Kg2 R8d4? 29...h3+! 30.Kxh3 Rh1+ 31.Kg2 Rh2+! is a sly fork trick! 32.Kf3 Rf8= 30.Nxf6 Kxf6 31.Qxh6+ Kf7 32.c3 Rd6 33.Qxh4 R1d2 34.Qh5+ Ke6 35.Qg6+ Kd5 36.Qf7+ Kc6 37.g4 Rxb2 38.g5 And White won on move 67. 8.4 Costel Voiculescu 2532 Reinhard Schiendorfer 2391 ICCF email 2012 1.e4 c5 2.Nc3 e6 3.Nf3 a6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 b5 6.Bd3 Qb6 7.Nf3 Qc7 8.0-0 Bb7 9.Re1 Bc5 10.Qd2!? Already noted in the previous edition as a way to set up b2-b4. 10...Ne7 A) 10...Be7!? 11.b4!N (the queenside plan succeeds even against Black’s prophylaxis) 11...Nf6 12.a4 0-0 (12...bxa4 13.Rxa4ƒ) 13.e5 Ng4 14.axb5 Now the play becomes very messy, but the complications heavily favour White: A1) The first stellar trap is 14...Bxb4? 15.Nd5! Bxd2 16.Nxc7 Bxe1 17.Nxe1 Ra7?! 18.b6+–; A2) 14...f5 15.h3! Bxf3 16.hxg4 Bxb4 17.Nd5! (this trick never grows old!) 17...Bxd2 18.Nxc7 Bxe1 19.gxf3 Ra7 20.Nxa6 Bc3 21.Ra4 Bxe5 22.f4 Bd6 23.Be3 Rb7 24.gxf5 exf5 25.Bc4+ Kh8 26.Be2± White is down an exchange, but Black is playing without a knight and b7-rook!; A3) 14...Bxf3 15.b6! Qxb6 16.gxf3 Qxf2+ 17.Qxf2 Nxf2 18.Kxf2 Bh4+ 19.Kf1 Bxe1 20.Kxe1 Nc6 21.Ra4 Nxe5 22.Bxa6 Nxf3+ 23.Kf2 Ne5 24.b5± As the dust settles, Black’s rook and pawns are no match for the precious bishop pair. B) 10...Qb6? 11.a3 Nc6 12.b4 Be7 13.Bb2 f6 14.Qf4± Ghaem Maghami-Wang Chen, Jakarta 2012. 11.b4! Bd6 12.a4 0-0 13.Rd1!? 13.Bb2 Bxb4 14.Nxb5 Bxd2 15.Nxc7 Bxe1 16.Rxe1 Bxe4 17.Bxe4 Ra7= 13...Rc8 14.Bb2 Bf4 14...Bxb4 is less effective now: 15.Nxb5 Qa5 16.c3 Bc5 17.Nbd4² and White is ready to boot Black back with Nb3 and c4-c5. 15.Qe1 15...Bd6 15...Nbc6 16.g3 Nxb4 17.gxf4 Qxf4 18.Qe3 Nxd3 19.cxd3 Qxe3 20.fxe3 b4 21.Nb1± understandably didn’t appeal to Black. 16.Nxb5! axb5 17.e5 Bxb4 18.Qxb4 Nbc6 19.Qh4 Ng6 20.Bxg6 fxg6 21.axb5 Rxa1 22.Rxa1 Na5 23.Qb4 Nc4 24.Bd4± Qd8 25.b6 Qf8 26.Qxf8+ Kxf8 27.Ra4! Now it’s just a matter of breaking the light-square blockade. 27...Bd5 28.h4 Rb8 28...Ke8 29.Kh2 Ra8 30.Rb4+– 29.Bc5+ Kg8 30.Nd4 Rc8 31.Nb3+– h6 31...Nxe5 32.Bd6 Nc4 33.Bc7 Nxb6 34.Bxb6 Rxc2 35.Nc5 32.Rb4 Rb8 33.f3 Rb7 34.Kf2 Kf7 35.Bd4 Rb8 36.Ke2 d6 37.Kd3 Nxe5+ 38.Bxe5 dxe5 39.Na5 Ke7 40.b7 Kd7 41.c4 1-0 8.5 Corky Schakel 2328 Paulo Leal 2340 ICCF email 2013 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3 b5 6.Bd3 Qb6 7.Nf3 Qc7 8.0-0 Bb7 9.Re1 Be7 10.e5 f5 11.Nd4 g6 12.Bf1 Nc6 13.Nxc6 Bxc6 14.Be3 h5 15.a4 b4 16.Ne2 g5 A) 16...Nh6?! 17.Nf4 Kf7 18.a5! Kg7 19.Bb6 Qb7 20.Qd4± paralyses Black; B) 16...Rh7 17.Nd4 (17.Nf4? g5!) 17...Bd5 gives White a couple of neat plans: 18.Bd2 (18.Nf3!? Nh6 19.Ng5 Rh8 20.Qd2 Nf7 21.h4² fixes the kingside before making queenside inroads) 18...Nh6 19.c3 bxc3 20.Bxc3 Qb7 21.Rc1 Nf7 22.Nc2 Bb3 (Pepermans-Meyner, email 2013) and here I’d start with 23.Qd4! Nd8 24.a5² when Black must constantly watch for Bb4. 17.a5 h4 17...Rh7 18.Bb6 Qxe5 19.Nd4 Qd5 20.Rc1² 18.Bb6 Qb7 19.Nd4 Bd5 This was the key moment of the game, where White failed to take precautionary measures on the kingside before pushing his queenside agenda. 20.c4 20.h3! Nh6 21.c4 bxc3 22.bxc3 g4 23.hxg4 Nxg4 Black’s knight enters the fray, but eroding Black’s kingside space advantage is more important, and after 24.c4 Bc6 25.Rb1 even the line opening 25...h3 26.gxh3 Rg8 27.hxg4 Rxg4+ 28.Qxg4! fxg4 29.Nxc6 dxc6 30.Bd3 Kf7 31.Re4!ƒ doesn’t change his plight. 20...bxc3 21.bxc3 Rc8 22.Nxf5 exf5 23.Bxa6 Qxa6 24.Qxd5 Qa8 25.Qb3 g4 The threat of 26...h3 forces White’s hand, but Black’s defensive resources prove satisfactory. 26.e6 dxe6 27.Qxe6 h3 28.gxh3 Rc6 29.Qxf5 gxh3 30.Bd4 Rhh6! 31.f3 Qc8 32.Qxc8+ 32.Qd5 Kf8 33.Kh1 Bf6= 32...Rxc8 33.a6 Ra8 34.a7 Kd7 35.Reb1 Kc8² 36.Ra4 36.Ra5!? Bd6! 36...Rc6 37.Ra5 Nf6 38.Re5 Bd6 39.Rg5 Ra6 40.Rg7 Nd7 41.Rg8+ Bf8 42.Rb2 Kc7 43.Kf2 R6xa7 44.Bxa7 Rxa7 45.Rh8 Ra3 46.Rc2 Bc5+ 47.Ke2 Nf6 48.Rxh3 Nd5 49.Rh7+ Draw agreed. Chapter 9 The Paulsen 5.Nc3 Qc7 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3 Qc7 The most flexible and strongest continuation. 6.Bd3 While Nc3 is less flexible than the 0-0/c2-c4 set-up, we’ve avoided ...Bc5/...g7-g6 set-ups in the process. Alternatives to 6...Nf6 A) 6...Bb4 proves an empty shot after 7.0-0 Bxc3?! 8.bxc3 Qxc3?! 9.Rb1! and Bb2 will finish Black on the dark squares; B) 6...Ne7!? requires a prophylactic treatment: 7.Be3 Nec6 (7...Nbc6? 8.Ndb5! axb5 9.Nxb5 Qa5+ 10.Bd2 and Nd6 wins material) 8.Nb3 d6 9.0-0 Be7 10.f4 0-0 11.Ne2!² with good attacking chances after c2-c3/Ng3; C) 6...g6?! 7.Be3 Bg7 8.Qd2 is unpleasant for Black, as ...Nf6 will be met with Bh6, and 8...Nc6 9.Be2 Nge7 10.Nxc6N 10...bxc6 11.Bf4 Qb7 12.0-0-0 d5 13.Bh6 0-0 14.Bxg7 Kxg7 15.h4! is also hard to defend; D) 6...Bd6 is artificial, and can be met in several good ways: 7.Qg4 (7.Rf1!?N looks strange but is not so easy for Black to meet, e.g. 7...Nc6 8.Nxc6 bxc6 9.Qg4 Kf8 10.Bd2 and White has better deployment) 7...Be5 (7...h5 8.Qg5 Be7 9.Qg3 d6 10.Be3 is a good Scheveningen for White, as ...h7-h5 feels out of place) 8.Be3 Nf6 9.Qh4 Nc6 10.Nxc6N 10...Qxc6 11.0-0!² – it is too risky for Black to take on c3, but otherwise his set-up does not make sense; E) 6...Bc5?! 7.Nb3 Be7 (7...Ba7?! 8.Qg4 Kf8 9.Bf4 also prompts severe concessions) 8.Qg4! We already know this motif – ...Be7 is well met by Qg4. 8...g6 (it looks too ugly to play 8...Kf8 9.f4 h5 10.Qf3±) 9.Bg5! and Black struggles to hold back White’s superior development, see Carlsen-Kveinys, Reykjavik 2006; F) 6...Nc6 7.Nxc6 F1) 7...bxc6!? is tricky... ... as we’ve transposed into the 5...a6 Taimanov. Fortunately, 8.Qf3! Nf6 9.Qg3 Qxg3 10.hxg3 d5 11.f3 and g4-g5 exploits Black’s move order for a small endgame edge in the spirit of the 7.Qf3 Taimanov; F2) After the standard 7...dxc6 8.0-0 Black can’t really avoid a transposition to 6...Nf6 7.0-0 Nc6, for instance: 8...e5 9.f4 Bc5+ 10.Kh1 Ne7?! 11.Qh5! and f4-f5 is too strong; F3) 7...Qxc6 8.0-0 Black suffers for his lack of development: F31) 8...Ne7 was once played by Grischuk, but 9.Be3N 9...Ng6 10.Qh5± and f4-f5 is tough to parry; F32) 8...d6 9.f4 Nf6 is likewise a bit passive: 10.Be3! Be7 (or 10...Bd7 11.Qf3 Be7 12.a4 with a bind) 11.e5! Nd7 12.exd6 Qxd6 13.Qf3 0-0 14.Rad1 and Black has issues continuing his development; F33) 8...b5 9.Re1 Bb7 (9...Ne7 avoids the Nd5 trick but doesn’t change the assessment after 10.a4 b4 11.Na2 Ng6 12.Bd2 Rb8 13.c3 bxc3 14.Bxc3ƒ) 10.a4 b4 11.Nd5! Nf6 12.Bd2ƒ White has the initiative, as depicted in Caruana-Bui, Budapest 2007. 6...Nf6 7.0-0 The most flexible, though Black in turn has a broad choice and there’s a lot of room for both sides to improve on existing theory. 7.f4 was the old recommendation and remains a challenging option, but 7...Bb4! is tough to prove anything against, as we’ll see in Ivanchuk-Nakamura, Bilbao 2011. (The most common move 7...d6 gives White more chances with 8.Qe2!, based on Grischuk-Timofeev, Sochi 2017 among others.) Unusual seventh moves A) 7...Bb4 makes less sense now after 8.Bd2, and with 9.Ncb5 threatened, Black will probably have to move the bishop again. 8...Nc6 (8...Bd6 gives us the extra option of 9.Nf3!?N 9...Nc6 10.Qe2 0-0 11.h3! (nipping ...Ng4 in the bud) 11...Ne5 12.Rae1 Nxf3+ 13.Qxf3 Be5 14.Qe3² and f2-f4 will give White an improved Scheveningen) 9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.f4 d5 11.e5 Nd7 12.Na4 Bxd2 13.Qxd2 c5 14.c4 d4 15.b4 cxb4 16.c5! Bb7 17.Qxb4ƒ and White has won the queenside battle; B) 7...h5?! is a bit too coffeehouse after something simple like 8.h3 Bc5 9.Nb3 Ba7 10.Qf3² followed by Be3 to trade Black’s sniper; C) 7...Bd6 8.Kh1! Nc6 (8...Bxh2?? 9.f4 Bg3 10.Qf3 Bh4 11.Qh3+–) 9.Nxc6 dxc6 10.f4 e5 11.f5 and White has a small edge, as in the model game Najer-Artemiev, Sochi 2017. It’s true that we were move-ordered out of our preferred answer to 7...Nc6, but at the same time Black’s bishop is misplaced on d6 when we play f4-f5; D) If 7...b5 8.Re1! sets up both e4-e5 and Nd5: D1) 8...Nc6 9.Nxc6 Qxc6 10.Bd2 Bb7 11.a4 (11.Nd5!N is an improved version) 11...b4 12.Nd5 transposes to 6...Nc6 7.Nxc6 Qxc6; D2) 8...Bd6?! is rarely published in practice: 9.e5! Bxe5 10.Ndxb5 axb5 11.Nxb5 Bxh2+ 12.Kh1 Qc6 13.Kxh2 with a very visible advantage; D3) 8...d6 9.a4 b4 10.Na2 e5 (10...Bb7?! 11.Nxb4 d5? fails to 12.Nxd5! exd5 13.exd5+ Kd8 14.Bg5+– Kislov-Pecha, Frydek Mistek 2009) 11.Nf3 (11.Ne2!?N) 11...Nc6 12.Bd2 Qb7 (or 12...Rb8 13.Rc1N 13...Be7 14.c3 bxc3 15.Rxc3! Qb7 16.b4!ƒ and Black is getting pushed back) 13.c3 bxc3 14.bxc3! and Black’s backward development is the cause of his woes; D4) 8...Bc5?! 9.e5! Bxd4 10.exf6 Bb7 (else Nd5) 11.fxg7 Bxg7 12.a4!± was already close to winning in ThompsonKarayilan, email 2013, as 12...b4 meets with the shot 13.Qg4!; D5) 8...Bb7 9.e5 Nd5 (9...b4? 10.exf6 bxc3 11.fxg7 Bxg7 12.bxc3 Qxc3?! tactically fails to 13.Nf5! Qxa1 14.Nd6+ Ke7 15.Nxb7 Qc3 16.Be4 with a winning attack) 10.Nxd5 Bxd5 11.a4 b4 12.Qg4! White is just better as Black can’t easily develop his kingside: 12...h5 (12...Nc6 13.Nxc6 Qxc6 (or 13...Bxc6 14.h4!? h5 15.Qg3±) 14.Qg3!?N (a promising square for the queen, getting out of ...h7-h5/...f7-f5) 14...f5 15.Be3 I struggle to find a constructive plan for Black, while White can improve his position with a4-a5 and h2-h4) 13.Qg5! Nc6 14.Nxc6 Qxc6 15.h4! Black has covered his weaknesses, but his long-term development problems will tell. E) 7...Nc6 8.Nxc6 and now: E1) 8...Qxc6? 9.e5 Nd5 10.Ne4±; E2) 8...dxc6 9.f4 e5 (necessary to avoid e4-e5; 9...Bc5+ 10.Kh1 e5 11.a4!? transposes, see the model game SprengerLuch, Pardubice 2005) 10.a4! (10.Qf3 gives Black the extra option of 10...b5, though 11.a4 b4 12.Nd1² nonetheless favoured White in Vallejo Pons-Nyzhnyk, Bahia Feliz 2011) It took some time to grasp this position and appreciate that Black needs to grab space with ...b7-b5 to have counterplay, and would much rather have his king in the centre than on the kingside when we play f4-f5, so Black may reply ...h7-h5. 10...Bd6 (for 10...Bc5+ 11.Kh1 see the model game Sprenger-Luch, Pardubice 2005) 11.f5 Bc5+ (11...a5 12.Qf3 Qe7 13.Kh1ƒ and Bg5 makes it hard for Black to get active; 11...b6 12.Qf3 0-0 13.g4! and g4-g5 shows the problem with kingside castling for Black) 12.Kh1 b6 This is the engine’s first line, but it looks artificial to move the bishop a second time, and I like 13.Qf3 Bb7 14.Bg5N 14...0-0-0 15.Nb1!², intending Nd2-b3; E3) 8...bxc6 Now we’ve transposed into the 5...a6 6.Nxc6 Taimanov from the previous chapter, but I cover the move order here. 9.Qf3!? (9.Re1 was analysed to a small edge by Negi. I couldn’t find any improvements over his analysis, so I’ve offered a less theoretical alternative that still challenges Black) 9...Bd6 (9...d5 10.Bg5 Be7 11.Rae1² is a dream setup for White, who intends e4-e5; 9...Be7 10.Re1 e5 11.Qg3 0-0 12.Bh6 Ne8 13.Rad1 is also a bit better for White, who can revert to positional play with Bc1, b2-b3 and Na4/c4) 10.Kh1 0-0 11.Qe2!N (with the bishop on d6, we should shift direction. 11.Bg5 Be5 12.Rae1 d5 13.exd5 exd5 14.Qe2 is not as good because of 14...Bxc3! 15.bxc3 Ne4 16.Bxe4 dxe4 17.Qxe4 Be6=) 11...Be7 (11...e5 12.Bg5 Be7 13.f4 d6 14.fxe5 dxe5 15.h3²) 12.e5 Nd5 13.Na4! White has a small edge due to Black’s worse structure. The flexible equaliser 7...Be7!? is rare but tricky. A) The point of Black’s move order is that 8.f4 is now met by 8...Bc5! 9.Be3 Nc6. Then 10.Nf5!? is an interesting idea, but I don’t see any pressure for White after 10...Bxe3+ 11.Nxe3 d6=; B) 8.Qe2 d6 (8...Nc6?! 9.Nxc6 dxc6 10.e5 Nd5 11.Re1 0-0 12.Qg4 gives White a super attack) 9.f4 still gives White promising attacking chances: B1) 9...Nbd7 is the most common, but I found a new idea in 10.a4! Nc5 (10...b6?! 11.g4!ƒ) 11.g4!N which gives White an initiative after 11...h6 12.Qg2 0-0 13.Be3 e5 14.Nf5 Bxf5 15.gxf5 Kh8 16.Kh1; B2) 9...0-0 10.Kh1 and now: B21) 10...Nc6 is an inferior set-up because of 11.Nxc6 bxc6 12.e5 Nd5 13.Na4N 13...c5 (or 13...Nb4 14.Be3 Nxd3 15.exd6 Qxd6 16.cxd3 with pressure on the dark squares) 14.c4 Nb4 15.exd6 Bxd6 16.Be4 Rb8 17.Be3 Bd7 18.Nc3 and Black is unable to generate enough activity for his inferior structure. For instance: 18...f5 19.Bf3 Be7 20.Rad1 Rbd8 21.Bf2 Rfe8 22.g3²; B22) 10...Nbd7 11.Bd2 Nc5 (11...h6?!N 12.b4!² will resemble the 8.Kh1 line with 12.b4!; 11...b5 transposes to a 7...d6 line, where I note the trick 12.e5!) 12.b4 Nxd3 13.cxd3 This is the key position for the assessment of 8.Qe2. Objectively Black should be fine, but he struggles a bit in practice as we’ll see in Ma-Li, Zaozhuang 2015. C) 8.Kh1 C1) 8...Nc6!? 9.Be3! While we aren’t playing Bd3/Be3 against the Taimanov, here it’s the best move as we reach a good version with Black committed to ...Be7 (9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.Bg5 d5 11.f4 with a tiny edge is also possible). C11) 9...d5!? 10.exd5 exd5 is safe for Black, though not a full equaliser: 11.f4!?N (11.Qf3 Ne5! 12.Nxd5 Nxd5 13.Qxd5 Nxd3 14.cxd3 0-0 gave Black good compensation in Orlov-Yandemirov, St Petersburg 2000) 11...0-0 12.Qf3 Nb4 13.Nb3 White has a tiny edge after 13...Bd7 14.h3 Nxd3 15.cxd3² and Bd4; C12) 9...0-0 10.f4 d6 transposes; C13) 9...d6 10.f4 C131) 10...Bd7!? scores terribly but avoids our Nxc6 plan: 11.Qf3 0-0 (normally in the Scheveningen we’d have Qe1/Be2, which is a less aggressive set-up. If 11...h5?! 12.a3!? stops ...Nb4 and it’s hard for Black to justify the h-pawn advance: 12...Ng4 (12...h4 13.Nb3!² leaves Black’s minor pieces a bit jammed) 13.Bg1²) 12.Rae1 – see KamskyMamedyarov, Tromsø 2013, where I show that White has the easier game (though not an objective advantage). 12.Nb3!? followed by g4-g5 is a decent alternative; C132) 10...0-0 11.Nxc6 bxc6 12.Qf3! Black is under some pressure due to White’s extra space. 12...Bb7 (12...e5 halts White’s kingside intentions, but is a bit loosening after 13.fxe5 dxe5 14.h3! Be6 15.b3 and Na4/Rad1 keeps Black passive) 13.Qh3 Rad8 14.Rae1 (with 15.e5 threatened, we provoke Black’s structure forward) 14...e5 (or 14...c5 15.b3 Kh8 16.Bc1 g6 17.Bb2 d5 18.exd5 exd5 19.f5 d4 20.Ne2²) 15.fxe5 dxe5 16.Qf3 Bc8 17.Na4! c5 18.b3² White has full control of the queenside, and can steadily improve his position with Nb2-c4. C2) 8.Kh1 d6 9.f4 Black has a lot of move orders, each requiring a different reply, so you’ll have to excuse the maze of variations. C21) 9...0-0 10.Be3 b5 (10...Nbd7?! is now too slow after 11.g4!; 10...Nc6 11.Qf3 Bd7 transposes to 8...Nc6) 11.e5! In these structures, one should check on every move if this break is possible. 11...dxe5 12.fxe5 Qxe5 13.Qf3 (Black must part with the exchange) 13...b4 (if 13...Qc7 14.Qxa8 Bb7 15.Nxe6 fxe6 16.Qa7 Nbd7 17.Qd4 Qc6 18.Rf2 b4 19.Nd1 Nc5 20.Qh4! Nxd3 21.cxd3 and White’s extra exchange outweighs the strong long diagonal battery) 14.Bf4! (we would rather give up the knight than the bishop) 14...Qxd4 15.Qxa8 Nbd7 16.Rad1 Qb6 17.Na4 Qa5 18.Qc6 Nd5 19.b3 Nxf4 20.Rxf4 Ne5 21.Qb6 Qxb6 22.Nxb6 Black has reasonable compensation, but White keeps an edge with his small material advantage; C22) 9...Nbd7 10.Bd2! This pivotal move is geared against both ...Nc5 and ...b7-b5. 10...b5 (10...Nc5 11.b4 Nxd3 12.cxd3 0-0 13.Rc1² prevents Black achieving his desired ...b7-b5/...Bb7 set-up, and 13...Bd7 gives White several good plans, my favourite being 14.Qf3 followed by a steady kingside expansion (h2-h3/g2-g4); 10...b6!? 11.Qe2 Bb7 12.b4! (preventing ...Nc5) scores amazingly for White, as we’ll see in Dauga-Adams, email 2014. The engines insist Black is fine, but this is not supported by practice, where White’s attack is almost always successful; 10...0-0?! 11.g4! Nc5 12.g5 Nfd7 13.f5! Qb6 14.f6! gives White a monumental attack) 11.b4! Bb7 12.Qe2! 0-0 13.a4 bxa4 14.Nxa4! (14.Rxa4 is what I’d love to make work, but in the notes to Gao-Zhou, China 2015, I show why the pawn sacrifice 14...Rfc8! is an equaliser) 14...Rfe8 (14...d5 15.e5 Ne4 16.Be1! Nb6 17.Nb2! Rfd8 18.Qe3± constricted Black’s pieces in Degraeve-Van Wely, France tt 2017; 14...Rfc8 15.c4! nullifies the c-file pressure: 15...Rab8 16.Bc3² and Nb3-a5 might follow to strengthen the bind) 15.Nc3! (15.c4 e5! 16.Nf5 Bf8 17.Ng3 exf4 18.Bxf4 Ne5 19.Bxe5 Rxe5 left White overextended in Jensen-Ness, email 2010) 15...Bf8 16.Nb3 White was successful in Bok-Nijboer, Groningen 2010, but I show in the notes how Black can balance the game; Common but acquiescent 7...d6 8.f4 Black has various options, but he usually opts for the ...Nbd7/...b7-b5/...Bb7 set-up to try and justify not playing the 7...Be7 move order. A) 8...Bd7 is a curious move order: 9.Be3 Be7 (if Black delays ...Be7 by 9...Nc6 10.Qf3 Rc8, then 11.Qg3! is a suitable punishment. Note that Black gains nothing from 11...h5?! 12.h3 h4 13.Qf2 Be7 14.Nf3±) 10.Qf3 Nc6 11.Nxc6 (if there’s one thing the engines have taught us about the Open Sicilian, it’s that Nxc6 is often a good move in the early middlegame!) 11...Bxc6 (if 11...bxc6 12.g4!± is strong) 12.f5! e5 13.a4 0-0 14.a5² Black is starved of activity in this structure; B) 8...b6 is too slow after 9.g4!N 9...h6 10.Qe2; C) 8...g6 is possible in the Bind structure, but here it’s asking for too much: 9.e5! (9.f5 Bg7 10.Qe1!?N also looks promising) 9...dxe5 10.fxe5 Bc5 (10...Qxe5 11.Nb3!± and Bf4 left Black’s queen short of squares in VocaturoSiebrecht, Wijk aan Zee 2011) 11.exf6 Bxd4+ 12.Kh1± The pawn on f6 makes it hard for Black’s king to castle safely; D) 8...Nc6 9.Nxc6! bxc6 10.Qf3 is a promising set-up for White, as ...d6-d5 now takes an extra move, and ...e6-e5 weakens the structure: 10...Nd7 (10...Be7?! permits 11.e5!±; 10...e5?! 11.Na4 Be7 12.fxe5 dxe5 13.Be3 c5 14.b3 0-0 15.h3 is a dream structure for White; if 10...Bb7 11.b3 Be7 12.Bb2 0-0 13.Qg3 White’s pieces are perfectly positioned for a mighty e4-e5 break) 11.Qg3!N (the queen is often well placed here) 11...h5 12.Be3 h4 13.Qf3² Black’s position lacks harmony; E) When played early, 8...b5 as usual will get hit by a2-a4 sooner or later: 9.Qe2 Bb7 10.a4!? b4 11.Na2 Nbd7 (11...Nc6 12.Be3 d5 13.e5 Ne4 14.Nxc6 Qxc6 15.c3! bxc3 16.Nxc3 opens the position for White’s better developed pieces; 11...d5 12.e5 Ne4 13.Be3 Nd7?! 14.c3! bxc3 15.Rac1 Bc5 (Pähtz-Kasparov, München 2002) would be losing for Black if White finds 16.b4!±) 12.Nxb4 Nc5! (or 12...Be7 13.c3²) 13.e5 dxe5 (Black does not earn enough for his pawn in the event of 13...Nfe4 14.c3 Nxd3 15.Nxd3 dxe5 16.fxe5²) 14.fxe5 Nfd7 15.Bf4 Be7 16.Rad1 0-0 17.c3² White is fully mobilised and has an extra pawn; F) 8...Be7 is inaccurate as we can now play more actively: 9.Qf3! (9.Kh1 Nbd7 10.Bd2 transposes to 7...Be7) and now: F1) 9...Nbd7 10.a4 – White is now ready to sound the charge with g2-g4-g5: 10...b6 (10...Nc5 11.Be3 0-0 12.g4!² is tough to parry) 11.g4! h6 (11...g5!? 12.fxg5 Ne5 13.Qg3 Nfxg4 is a nice idea but it doesn’t work: 14.h3 Nxd3 15.cxd3 Ne5 16.Nde2!±) 12.Qh3 and Black must contort to avoid g4-g5; F2) 9...0-0 10.Be3 and now: F21) 10...b5 is hit by 11.e5 dxe5 12.fxe5 Qxe5 13.Rae1! Bc5 14.Kh1 Bxd4 15.Bxd4 Qxd4 16.Qxa8 Nbd7 17.Qf3 and I don’t see Black’s compensation for the material; F22) 10...Nbd7?! is common but weak after 11.g4! Nc5 (after 11...g6 12.g5 Nh5 13.f5 Ne5 14.Qh3 Black will do well to survive to move 30) 12.g5 Nfd7 13.Rac1! (prophylaxis against ...Nxd3 – otherwise what is the knight doing on c5?). 13...Re8 14.b4 Nxd3 15.cxd3 Qd8 16.h4 Bf8 17.h5 and Black had the dubious distinction of all but one of his pieces on the back rank in Petrov-Benitah, Lyon 2007; F23) 10...Nc6 11.Rae1² (unlike after 7...Be7, we have saved a tempo on Kh1) 11...Bd7 (the robust 11...Nxd4!? 12.Bxd4 e5 13.Be3 makes it hard for Black to easily release the tension: 13...Bd7 (13...Bg4 14.Qg3 Bd7 gives us options with 15.Nd5!? Nxd5 16.exd5²) 14.a3N 14...Rae8 15.Kh1² It’s a normal position, but White has slightly more space and better pieces) 12.a3 and now: F231) 12...Nxd4 13.Bxd4 Bc6 14.Qg3 and e4-e5 will garner an initiative; F232) 12...Rac8 13.Qg3 b5 Even in a good Scheveningen (with Bd3 in one go), White must still be precise to prove an edge! 14.Kh1 Black will get hit with e5 if he tries to keep this position, so direct play is advised: 14...Nh5 15.Qh3 Nxd4 16.Qxh5 (16.Bxd4 Nxf4! 17.Rxf4 e5= is Black’s idea) 16...g6 17.Qg4 f5!, but this counterthrust is double-edged and after the logical 18.Qg3 Bf6 19.Qf2 Nc6 20.Bb6 Qb8 21.exf5 gxf5 22.a4 Nb4 23.Bd4! White has some pressure due to Black’s weakened structure and king; F233) 12...b5 13.Qg3 Rab8 14.Kh1! The engines slightly underestimate White’s attacking chances here. To give an illustration: F2331) 14...Kh8 15.Nxc6 Bxc6 16.Bd4² makes it hard for Black to avert e4-e5. A good example (by transposition) is 16...Rbd8 17.e5! dxe5 18.Bxe5 Qb7 19.Qh3 h6 20.Ne4 Ng8 and White had a dominant position in Popilski-Urkedal, Croatia tt 2007, and could have induced further weaknesses with 21.Qg3!? f6 22.Bc3±; F2332) 14...b4 15.Nxc6 Qxc6 (15...Bxc6 16.axb4 Rxb4 17.f5! is dangerous) 16.axb4 Rxb4 17.Bc1² White has a clear plan of e4-e5/f4-f5, while Black remains passive (17.f5!? is also good). G) 8...Nbd7 9.Kh1 (9.Bd2!? is almost untried but limits Black’s options somewhat, as the critical 9...Qb6 (9...b6 10.Qe2 Bb7 11.b4!² allows White to save on Kh1; 9...b5 10.Qe2 Bb7 leaves nothing better than 11.Kh1 anyway, transposing) 10.Be3 Qxb2 11.Ncb5! axb5 12.Nxb5 favours White – actually, we’ve transposed to a Scheveningen trap: 12...Qb4 (on 12...Ra5? 13.Rb1 Rxb5 14.Rxb2 Rxb2 15.Qa1 Rb6 16.Bxb6 Nxb6 17.Qc3 Be7 18.Rb1 was supremely strong in Anand-Kasparov, Tilburg 1991, as Black’s pieces are not in time to coordinate against the queen) 13.Nc7+ Ke7 14.Nxa8 Qa5 15.e5! (the key move, not giving Black time to consolidate) 15...Ne8 16.exd6+ Nxd6 17.c4 Qxa8 18.c5 Ne8 19.f5! White had the attack in De Firmian-Gheorghiu, Lone Pine 1980) 9...b5 (9...b6 10.Bd2 Bb7 11.Qe2 is likely to transpose to 7...Be7. Instead 11...h5?! 12.b4! hardly leaves better than 12...Be7 anyway; 9...Be7 transposes to 7...Be7) 10.Qe2! (10.Bd2 b4!N is annoying) G1) 10...b4?! is now too weakening after 11.Na4 Nc5 12.Nxc5 dxc5 13.Nf3 and with the queen on e2, ...c5-c4 is not possible: 13...Be7 14.b3!? 0-0 15.Bb2²; G2) 10...Be7 11.Bd2 0-0 (11...Nc5? is just a blunder because of 12.e5!+–; 11...Bb7 transposes to 10...Bb7) 12.e5!? I like this way of exploiting the delayed ...Bb7. 12...dxe5 13.fxe5 Qxe5 (13...Nxe5?! 14.Bf4 Bd6 15.Ndxb5! axb5 16.Nxb5 Qc5 17.Nxd6 Nxd3 18.Qxd3 was a clean extra pawn for White in Lekic-Smith, Paracin 2015) 14.Nc6 Qc5 15.Qf3 Bd6 16.Be3!N 16...Qh5 17.Qxh5 Nxh5 18.Rad1 (Black can’t keep his extra pawn anyway. 18.Be4!?ƒ and Ne7 may be even better) 18...Nhf6 19.Bxh7+ Kxh7 20.Rxd6 Bb7 21.Na5 gives White some endgame initiative; G3) After 10...Bb7 11.Bd2 Black has a broad choice, but b2-b4/a2-a4 is effective against most tries: G31) 11...Be7 12.b4! transposes to the 7...d6 main line; G32) 11...b4?! 12.Na4 Nc5 (12...a5?! 13.c3 Be7 14.Rac1± is a familiar theme to us by now; 12...e5 13.Nf5² – one can follow Vuckovic-Nikolov, Valjevo 2011) 13.Nxc5 dxc5 14.Nf3 Be7 15.e5 Nd5 Now in Belkhodja-Pliester, Dieren 1988, White could engineer heavy pressure with 16.f5! exf5 17.Bxf5±; G33) 11...h5?! I know some players who like to play this move in every position, but here it’s not warranted: 12.b4! h4 13.a4 bxa4 14.Rxa4±; G34) 11...g6!? is the one set-up where we should switch to the e4-e5 break: 12.Rae1! (12.b4 Bg7 13.a4 is now met by 13...Nh5!) 12...Bg7 (Black’s attempts to hold off e4-e5 don’t work: 12...e5 13.fxe5 dxe5 14.Nb3²; 12...Qb6?! 13.Nb3) 13.e5 dxe5 14.fxe5 Qxe5!N (a nice transformation in a difficult situation. 14...Nd5? 15.Ndxb5 axb5 16.Nxb5 Qxe5 17.Qf2 was killing in Juroszek-Bosboom, Biala 1988) 15.Qxe5 Nxe5 16.Rxe5 Nd7 17.Re4 Bxe4 18.Bxe4 Rc8 19.Nce2² White’s pieces coordinate well; G35) 11...Nc5!? 12.b4 (12.e5 dxe5 13.fxe5 Nfd7 14.Rae1 Be7!=) 12...Nxd3 13.cxd3 (this is a good version of the structure for White, as we can weaken Black’s queenside with a2-a4) 13...Be7 14.Rfc1 Qd7 15.a4 bxa4 16.Nxa4 Bd8 17.Be3 0-0 18.Nb2!? Rc8 19.Rxc8 Qxc8 20.Nc4 Qd7 21.Na5 and White had steady pressure in Juarez de Vena-Vieito Soria, email 2014. The most frequent move 7...Bc5 This variation has scored well for Black in recent games and is where I initially had the hardest time proving an advantage, as our knight being on b3 instead of d4 somewhat reduces our active options. On the other hand, the variations here are a bit more linear than in the last two sections! 8.Nb3 Be7 8...Ba7?! This could prove a strong diagonal if White plays on autopilot, so I recommend 9.Qf3! Nc6 (9...d6 10.Qg3 0-0 11.Bg5 Nbd7 12.a4 Kh8 13.Qh4! gave White the foundation for a successful attack in Palac-Drabke, Dresden 2003) 10.Bg5 Ne5 (10...Qe5 11.Bf4 Qh5 12.Qxh5 Nxh5 13.Bd6! is awkward) 11.Qg3 Now we have an amusing dance of the queen and knight, with the result that White obtains an improved Scheveningen: 11...Nh5 12.Qh4 h6! 13.Bd2 Nf6 14.Qg3 Nh5 15.Qh3 Nf6 16.Kh1 d6 17.f4 Nxd3 (17...Nc4? tactically fails to 18.e5! dxe5 19.Bxc4 Qxc4 20.fxe5 Nd7 21.Qg3+–) 18.cxd3 0-0 19.Rac1± The second wave of attack with e4-e5/Ne4 is coming. 9.f4 d6 9...d5?! 10.e5 Nfd7 11.Be3 is the familiar transition to an improved French for White. 10.e5! This is not only strong but practical, as White can choose between an edge and a draw depending on the tournament situation. 10.g4!? h6 11.Qf3 Nbd7 12.Qh3 was my initial recommendation, but I couldn’t crack 12...Nh7!= and the continuation of two drawn correspondence games. 10...dxe5 10...Nfd7 is too passive: 11.exd6 Bxd6 (or 11...Qxd6 12.Be3² Topalov-Svidler, Astana blitz 2012) 12.Ne4 (or 12.Be3²) 12...Be7 13.Bd2 0-0 14.Qh5 f5 (an ugly move, but necessary to stop White’s attack) 15.Ng5 In the model game NajerRodin, Olginka 2011, Black should have settled for 15...Bxg5 16.Qxg5 Nc6 17.Qg3². 11.fxe5 Nfd7! 11...Qxe5? 12.Bf4 Qh5 looks too good to be true and has been virtually refuted: 13.Be2 and now: A) 13...Qh4 14.g3 Qh3 might be played if Black is desperate to avoid a repetition, but 15.Ne4! leaves Black in big trouble: 15...e5 (if 15...Nxe4 16.Bg4 Qxf1+ 17.Qxf1 Nf6 18.Bf3±; if 15...Nbd7 16.Bc1!N eventually wins the queen by removing the f6-knight and following with Bg4) 16.Nd6+! Bxd6 (16...Kf8 17.Bxe5 Nc6 18.Bf4± is unplayable for Black with his king stuck on f8) 17.Qxd6±; see Kryvoruchko-Smirin, Plovdiv 2008, for the execution; B) 13...Qg6 14.h4! (the queen doesn’t receive any respite! 14.Bd3 Qh5 15.Be2 is the repetition, but we can do much better) 14...h5 (14...h6 15.h5 Qh7 16.Bd6± plays itself for White, Grishin-Jugl, email 2012) 15.Bg5 (Black’s game is already beyond salvation) 15...Qh7 (15...Ne4 16.Bxe7 Kxe7 17.Bd3 f5 18.Bxe4 fxe4 19.Qd4+–; 15...Ng8 16.Bd3 f5 17.Qe2 Nc6 18.Na4! b5 19.Nb6 Rb8 20.Nxc8 Rxc8 21.a4 Kf7 22.axb5 axb5 23.Bxb5 was a decisive initiative in Paragua-Bilguun, Jakarta 2013; 15...Ng4 16.Bxe7!N 16...Kxe7 17.Qd4 Rd8 18.Qc5+ Ke8 19.Bd3 Qh6 20.Rae1 leaves Black defenceless against knight penetrations after Ne4) 16.Bd3 Qg8 17.Qd2 Nc6 18.Rad1 Black is effectively playing without the queen and h8-rook, and should be lost with correct play. 12.Qg4 g6 White has a fabulous score from this position, but I was running into some theoretical problems until I found a big novelty. 13.Qg3!N We will have to move our queen anyway after ...Nxe5, so it’s sensible to anticipate the capture. I’ll briefly show why I rejected the alternatives, for our understanding of the variation. A) 13.Bh6 Nxe5! 14.Qg3 f5 15.Bg7 Bc5+ 16.Nxc5 Qxg7 White has compensation for the pawn, but not enough for an advantage. Even the novelty 17.N3a4!? doesn’t change the assessment after 17...b5 18.Rae1 Nbc6 19.Nb6 Qa7 20.Nxa8 Qxc5+ 21.Qe3 Nxd3 22.cxd3 Qxe3+ 23.Rxe3 Ke7 with full compensation for the exchange; B) 13.Bf4 Nc6 14.Qg3!? (14.Rae1 Ndxe5 15.Qg3 f6 is the usual line, but Black’s position is too solid: 16.Be4 0-0N 17.Bxc6 (17.Bxg6 hxg6 18.Rxe5 Nxe5 19.Bxe5 forces a draw if White wants it) 17...Qb6+ 18.Kh1 Nxc6 19.Bc7 Qa7 20.Na4 e5 21.Nb6 Be6 22.Nxa8 Qxa8= As usual, Black has returned the material to consolidate his long-term trumps) 14...g5!?N 15.Bxg5 Rg8 16.Ne4 Qxe5 17.Qxe5 Ncxe5 18.Bxe7 Kxe7 Perhaps White has a tiny endgame edge, but Black’s position is very safe. I did some work on 19.Ng3! Nxd3 20.cxd3 b6 21.Rae1 Bb7 22.Nd4 but found 13.Qg3 to be more promising. 13...Nc6 A) 13...Qxe5?! 14.Bf4 Qg7 15.Bd6 Nc6 16.Bxe7 Nxe7 17.Qd6!² keeps Black’s king in the centre just a bit longer: 17...Ne5 18.Rae1 N5c6 19.Ne4 0-0 20.Nf6+ Kh8 21.Be4 and Black can hardly move an inch; B) 13...Nxe5 14.Bf4 transposes to 13.Bf4 Nxe5 14.Qg3 while avoiding my 13...Nc6 14.Qg3 g5! novelty: 14...f6N (of course, one should defend with the least valuable piece where feasible. 14...Nbc6?! 15.Be4 forces 15...f6 anyway, as does 14...Nbd7? 15.Rae1 f6 16.Qh3 f5 17.Kh1±) 15.Be4 Nbd7 16.Nd4 Bc5 17.Rad1ƒ White’s advantage in force should not be discounted, especially since it is hard for Black to untangle: B1) 17...Qb6 18.Be3 Qxb2 Grabbing this second pawn looks awfully risky, and it’s quickly punished: 19.Nce2 Qa3 20.c3 Bxd4 21.cxd4 Nc4 22.Rd3 Qe7 23.Bh6ƒ and practically speaking Black’s position is close to indefensible; B2) 17...0-0 18.Kh1 Bxd4 19.Rxd4² White holds more than enough compensation for the pawn, with the bishop pair, development, initiative and weaknesses around the Black king to utilise. 14.Bh6 13.Bh6 Nxe5 14.Qg3 f5! is the problem correspondence line we averted. 14...Qxe5 14...Ncxe5? 15.Rae1 places Black in an awful pin, as in Zinchenko-Filip, Paleochora 2010 (among others). 15.Qf2 f5 16.Rae1 Qd6! It’s logical to keep the queen out of the range of White’s rooks. 16...Qf6 17.Qd2 gives White an enduring initiative. For example: 17...Rg8 18.Qe3 Nde5 19.Bf4 Nf7 20.Bc4 Kf8 21.Ne4! Qxb2 22.Nec5 Kg7 23.Bxe6 Bxe6 24.Nxe6+ Kh8 25.Qb6 Bf6 26.Qxb7 Nce5 27.Be3 Qxc2 28.Bd4² 17.Bb5!! An amazing silent sacrifice! A) 17.Qe3 b5 18.a3 Bb7 19.Qxe6 Qxe6 20.Rxe6 Kf7 is healthy for Black; B) 17.h3 is given by the engine as equivalent at a high depth, but it’s too subtle for my taste. 17...axb5 Or 17...Nf6? 18.Bf4 Qd7 19.Rd1±. 18.Nxb5 Play becomes very complicated now. 18...Qb4! 18...Qb8? 19.Rxe6 Nde5 20.Rxe7+ Kxe7 21.Qh4+ Kf7 22.Nc5 and Ne4 gives a powerful dark-squared attack for the rook, e.g. 22...Ra6 23.Ne4 Na7 24.Ng5+ Ke8 25.Bg7 Nxb5 26.Bxh8 and the attack persists. 19.Nc7+ Kf7 20.Nxa8 Bd8 The a8-knight is trapped, but not so easy to win. After 20...Bh4 21.g3 Bd8 we can still play 22.Qf4 as 22...Qb5 23.Nd2 Nce5 24.b4! Bf6 25.Ne4 gives an irrepressible initiative. 21.Qf4! This is the practical way, angling for a better endgame. 21.Qe2 e5! feels very unclear to me, despite the engine’s positive evaluation for White. 21...Qxf4 21...Qb5? 22.Nd2! e5 23.Ne4± 22.Bxf4 e5 23.Be3² Black has no way to trap the knight, so we can steadily play c2-c3, a2-a4 and go about freeing the steed. Summary 2...e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Bd3: 6...Nc6 7.Nxc6 bxc6 – +0.35 6...Nc6 7.Nxc6 Qxc6 – +0.50 6...Nf6 7.f4 – +0.10 6...Nf6 7.0-0: 7...Bd6 – +0.30 7...b5 – +0.55 7...Nc6 – +0.25 7...Be7 8.Qe2 – +0.15 7...Be7 8.Kh1 – +0.15 7...d6 – +0.25 7...Bc5 – +0.35 9.1 Magnus Carlsen 2625 Aloyzas Kveinys 2517 Reykjavik 2006 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Bd3 Bc5 7.Nb3 Be7 8.Qg4 g6 9.Bg5 d6 A) 9...b5 10.Bxe7 Nxe7 11.Qg3 Qxg3 12.hxg3±; B) 9...h5 10.Qh4 d6 11.0-0-0 Nd7 12.Bxe7 Nxe7 13.Be2±; C) A useful illustration of Black’s difficulties finding counterplay is 9...Nc6 10.Bxe7 Ngxe7 11.0-0-0 b5 12.a3 b4 13.axb4 Nxb4 14.Qh4 Bb7 15.Qf6 Rf8 16.f3 and the dark squares ache. 10.Bxe7 Nxe7 11.0-0-0 e5 12.Qg5 Be6 13.f4! In his youth Carlsen was a very tactical player and that flair shines in this game. 13...Nd7 14.f5! f6 A) 14...Bxb3 15.axb3 h6 16.Qh4 g5 17.Qe1±; B) 14...h6 15.Qh4 gxf5 16.exf5 Nxf5 17.Bxf5 Bxf5 grabs a pawn, but after 18.Rd2!± the d6-pawn will be the next casualty. 15.Qh6 Bxb3 15...gxf5 16.exf5 Bf7 17.Bb5! is a sweet tactic: 17...0-0-0 18.Bxd7+ Qxd7 19.g4± 16.cxb3 16.axb3 and Qg7 is even stronger, but White wants to open the c-file for the attack. 16...0-0-0 17.Kb1± Kb8 18.Rc1?! 18.g4! 18...Nc5 19.Bc2 gxf5 20.exf5 d5 21.Qxf6 Nc6? A tactical oversight, just when 21...Rhf8 22.Qg7 Qd6 23.Rhd1 d4 would bring Black back into the game. 22.Nxd5! 1-0 9.2 Fabiano Caruana 2523 Vinh Bui 2483 Budapest 2007 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Bd3 b5 7.0-0 Bb7 8.Re1 Nc6 9.Nxc6 Qxc6 10.a4 b4 11.Nd5 Nf6 12.Bd2ƒ Nxd5 12...Bc5 13.Nxf6+ gxf6 14.c3 leaves Black’s king unsafe for the future: 14...Qb6 15.Qf3 bxc3 16.Bxc3 Bd4 17.a5 Qc5 18.Bxd4 Qxd4 19.Rad1 Qe5 20.b4± 13.exd5 Qc5? Now Black is blasted off the board with consecutive threats. A) 13...Qxd5? 14.Be4; B) 13...Qd6 14.dxe6 dxe6 is sturdier, but still disappointing for Black after 15.Qg4! h5 16.Qg5 Qd4 (16...Qc5!?) 17.Bg6! Bd5 18.c3 bxc3 19.Bxc3 Be7 20.Bxf7+ Kxf7 21.Qxe7+ Kxe7 22.Bxd4±. 14.Be4!+– 0-0-0 14...Bxd5? 15.Be3; 14...e5 15.d6! 15.Be3 Qc7 16.c3! bxc3 17.Rc1 Bb4 18.Qd4 exd5 19.Qxb4 dxe4 20.Bb6 Qe5 21.Rxc3+ Kb8 22.Bd4 1-0 9.3 Vasily Ivanchuk 2765 Hikaru Nakamura 2753 Sao Paulo/Bilbao 2011 (6) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Bd3 Nf6 7.f4 Bb4! 8.Nb3 A) 8.Nf3!?N may be White’s best, but Black can equalise with fairly natural play: 8...d5 (8...Bxc3+ 9.bxc3 d6 10.0-0! Qxc3 11.Rb1²) 9.e5 Ne4 10.Bxe4 dxe4 11.Ng5 Bxc3+ 12.bxc3 Qxc3+ 13.Bd2 Qd4 14.c3 Qd3 15.Qb1 0-0 16.Nxe4 Qxb1+ 17.Rxb1 b5 18.Nd6 Nc6= The d6-knight looks lovely but it will soon be traded by ...Ne7-f5(c8); B) 8.0-0!? Bc5 is a funny transposition to 7.0-0 Be7 8.f4 Bc5! (8...d6 9.Nf3) 9.Be3 Nc6 (9...d6 10.Kh1 Bd7 11.Qe1²) 10.Nf5 Ne7 11.Nxg7+ Kf8 12.Bxc5 Qxc5+ 13.Kh1 Kxg7 14.e5 Ne8 15.Ne4 Qc6 16.Qh5 h6 17.Rf3 Nf5 18.g4 Nd4 19.Rf2 d5! 20.Nf6 b6!= The engine gives 0.00 but this looks quite scary from a human perspective; C) 8.Bd2 Bxc3 9.bxc3 (9.Bxc3 Qxf4 10.Qe2 d6 11.Nf3 e5=) 9...d6 10.0-0 e5 is a typically nice structure for Black, and the creative 11.Qe1!?N 11...exd4 12.e5 dxe5 13.fxe5 Nd5 14.cxd4 b5= doesn’t have the desired effect. 8...Bxc3+ 9.bxc3 d6 10.Ba3 0-0 Black should prioritise his queenside development, to cover any pressure on d6: 10...Nbd7! 11.0-0 b5 12.Qd2 Bb7 13.Rae1 0-0 14.e5 dxe5 15.fxe5 Nxe5 16.Bd6 Qb6+ 17.Bc5 Qc7 18.Bd6= 11.Qd2 11.0-0! Nbd7 12.e5 dxe5 13.Bxf8 Kxf8 14.Qf3! Qxc3 15.Rae1² 11...Rd8 12.0-0 Nc6 13.Rf3 b5 14.Rg3 The unbalanced play causes even our elite protagonists to make mistakes. 14...Kh8?! 14...e5 15.f5 Nh5 16.Rg4 Nf4 is very safe for Black. 15.Rf1² Bb7 16.f5 16.Qe3 16...Rg8 17.Qg5 e5 18.Qh4 Ne7? 18...Nb8!= and ...Nbd7-f8 was necessary to cover against Rh3, Rff3 and Qxh7!. 19.Rh3+– d5 20.Nc5? 20.Bc1! Rgd8 21.g4+–; 20.Rff3! dxe4 21.Qxh7+ Nxh7 22.Rxh7+ Kxh7 23.Rh3# Such checkmates only appear on the big screen... 20...dxe4 21.Bxe4 Bd5 22.g4 h6? 22...Qc6! 23.g5 Nh7?! 23...Nxe4 24.Nxe4 Bxe4 25.Qxe4 Rad8 26.f6 Ng6± 24.f6 Ng6 After conducting a great attack, Ivanchuk (possibly in zeitnot) starts losing his way. 25.fxg7+ There was no need to involve Black’s rook in the defence: 25.Qg4! 25...Rxg7 26.Qxh6?! 26.Qg4!± 26...Rd8 27.Bxg6 fxg6 28.Rf6 Qc8 29.Rh4 Bf7? 29...Rdg8 keeps the game wide open. 30.Nd3? 30.Ne4! Rd1+ 31.Kg2 Re1 32.Qxg7+! is probably the key tactic Chucky missed: 32...Kxg7 33.Rxf7+ Kxf7 34.Nd6+ Kg7 35.Nxc8+– 30...Kg8? Black’s last chance to save the game was 30...Rxd3! 31.cxd3 Qxc3 32.Bb4 Qxd3= when White’s exposed king makes a perpetual inevitable. 31.Bd6!+– e4 32.Be5 Rd5 33.Rc6 Qf8 34.Bxg7 Qxg7 35.Rxe4 Rxg5+ 36.Qxg5 Nxg5 37.Rc8+ Be8 38.Rcxe8+ Kh7 39.Rh4+ 1-0 9.4 Alexander Grischuk 2750 Artyom Timofeev 2555 Russia tt 2017 (1) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 a6 3.Nc3 e6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 Qc7 6.Bd3 Nf6 7.f4 d6 8.Qe2! Compared to 7.0-0, White can sound the g4-g5 charge in many lines. 8...Nbd7 A) After the infrequent 8...Be7!? White may try the interesting pawn sacifice 9.e5 dxe5 10.fxe5 Nfd7 11.Bf4 Bb4 12.00!?, e.g. 12...Bc5 13.Qe3!. This requires further analysis. Also the flexible 9.Bd2, waiting for 9...Nfd7 to play 10.g4!, is promising; B) 8...g6 is too slow, and should be met assertively with 9.e5 dxe5 (9...Nfd7 10.exd6 Bxd6 11.f5 with attack) 10.fxe5 Nfd7 11.Ne4! Qxe5 12.c3, securing a strong initiative after 12...f5 13.Nf3 Qc7 14.Neg5 Nc5 15.Bc2 Bg7 16.Be3ƒ; C) 8...Nc6 9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.0-0 is a good version of this structure for White: 10...Nd7 (10...e5 11.fxe5 dxe5 12.h3! Bc5+ 13.Kh1²) 11.Na4 Be7 12.c4 c5 13.b3 Bb7 14.Bb2 0-0 15.Rad1ƒ White is flexibly placed to support e4-e5 or f4f5. 9.g4 9.a4!? might be the more accurate move order: 9...Nc5 (9...b6 10.g4! with attack) 10.Be3 Be7 11.0-0 0-0 12.g4!?N 12...e5 13.fxe5 dxe5 14.Nf5 Bxf5 15.Rxf5 Nxd3 16.cxd3² 9...Nc5?! A) 9...g6?! 10.Be3 b5 11.a3²; B) 9...h6 10.Bd2 (10.g5 hxg5 11.fxg5 Nh5 12.g6 Ne5 13.gxf7+ Qxf7 14.Rf1 Nf6 15.Bg5 Qh5 16.h4 Qxe2+ 17.Bxe2 Be7=) 10...Nc5 11.Rf1!? (the kingside advance is not without repercussions: 11.f5 b5 12.b4 Nxd3+ 13.cxd3 e5 14.Nb3 d5! 15.Rc1 Qd8=) 11...b5 12.a3 Be7 With ...Nxd3 and ...e6-e5 at the ready, Black has a fair share of the chances. 10.g5 Nfd7 11.Bd2 11.Be3 is better, to defend the knight against ...g7-g6/...Bg7: 11...b5 12.a3 Bb7 13.Rf1 Rc8 14.h4 Nxd3+ 15.cxd3 Nc5 16.h5 and White’s king is rather safe in the centre. 11...g6! 12.f5 12.h4 Bg7 13.Nf3 b5 14.h5 Rg8! 15.h6 Bh8= 12...Ne5= 13.h4 Bd7 14.Rf1 0-0-0!? 14...Qb6! 15.Nb3 Nexd3+ 16.cxd3 Nxb3 17.axb3 Qxb3 18.fxe6 Bxe6 19.Nd5 Bg7! 20.Nc7+ Ke7 21.Nxa8 Rxa8= 15.0-0-0 Bg7?! Two tempi is too high a price for provoking 16.f6; 15...Kb8 gave counterplay. 16.f6! Bf8 17.Kb1² h6 18.Rh1 Kb8 19.h5 Better was 19.Nf3. 19...hxg5 20.hxg6 Rxh1 21.Rxh1 Nxg6 22.Bxg5 Bc8 22...Ne5!= 23.Rh7 23.Qf2!? Nxd3 24.cxd3 23...Nxd3 Black underestimates the danger, failing to free his pieces with 23...d5! 24.exd5 Nf4 25.Bxf4 Qxf4 26.Qh2 Qxh2 27.Rxh2 exd5=. 24.Qxd3 Ne5?! 24...d5 25.exd5 exd5= 25.Qg3 Ng6? 25...Bd7 26.Nf3!; 25...Qc4!? 26.Bc1 b5 27.a3 Ka8? 27...Ne5 28.Nf3 Nxf3 29.Qxf3+– 28.Qxg6! Qxc3 29.Qxf7 Qxd4 30.Qc7 1-0 9.5 Evgeny Najer 2682 Vladislav Artemiev 2682 Russia tt 2017 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Bd3 Nf6 6.0-0 Qc7 7.Nc3 Nc6 7...Bd6 8.Kh1 Nc6 9.Nxc6 dxc6 10.f4 e5 11.f5 is the rare but annoying move order which forces us to have some flexibility against ...Nc6 plans. 8.Nxc6 dxc6 9.f4 e5 10.Kh1 10.a4 10...Bd6 11.f5² b5 A) 11...b6 12.Qe1!? Bb7 13.Qg3 Rg8 14.Be3²; B) 11...Bc5 12.Qf3 b5 13.a4 Bb7 14.Qg3 Kf8 15.Bg5ƒ; C) 11...h5 is a typical move, but we can manoeuvre to attack the kingside weaknesses: 12.Be3 Qe7 13.Qe1! b5 14.a4N 14...Bb7 15.Bg5² and Black’s king is not sitting pretty. 12.a4 12...Bb7 A) 12...b4? 13.Nb1 Bb7 (13...a5 14.Qf3 h5 15.Nd2 Bc5 16.Qg3 Kf8 17.Nc4±) 14.Nd2 c5 15.Nc4 0-0 16.Qf3 a5 17.g4±; B) 12...Rb8 13.Be3 (13.Qf3!? h6 14.Nd1 is also promising, considering that from e3 our bishop sometimes moves to g5 again) A) 13...0-0 14.g4! with attack; B) 13...Be7!? 14.Qf3 Bb7 15.Qg3 constitutes a promising formation: 15...Kf8 (15...0-0 enables some trickery with 16.Bh6 Nh5 17.Qg4 Qd6 18.f6! Bxf6 19.Qxh5 gxh6 20.axb5 axb5 21.Qxh6 Be7 22.Qe3²) 16.axb5 axb5 17.h3 h6 18.Qf2²; C) 13...Qe7 14.Qf3 Bc5 15.Bg5 0-0 16.axb5 axb5 17.Nd1 h6 18.Bh4 Qd8 19.Nf2² 13.Be3 A) 13.axb5 axb5 14.Rxa8+ Bxa8 15.Bxb5 cxb5 16.Nxb5 Qc5 17.Qxd6 Qxb5 18.Rd1 Nd7 19.Bg5 f6= petered out to a draw in Zalcik-Bittner, email 2011; B) 13.Qf3 is more flexible: 13...h6 (13...h5?! 14.axb5 axb5 15.Rxa8+ Bxa8 16.Nd1! Be7 17.Nf2 h4 18.Bg5ƒ; C) 13...Be7! 14.Be3 h5 15.Nd1 Ng4 16.Bg1 Nf6 17.Ne3²) 14.Qg3 Kf8 15.Nd1 Kg8 16.Nf2 Be7 17.Be3 Kh7 18.c4! with a positional advantage. 13...h5? Now White gains a pawn. 13...Qe7! 14.Qf3 h6 15.Bf2 0-0 16.Nd1² is very solid for Black, but White’s f5-pawn gives attacking chances. 14.axb5 axb5 15.Rxa8+ Bxa8 16.Bxb5!± Najer conducts the rest of the game masterfully. 16...Bb4 17.Nd5 Nxd5 18.Qxd5 0-0 19.Qc4 Qa5 20.Ba6 Be7 21.Qe2 c5 22.Bd3 c4 23.Bxc4 Bxe4 24.Qxh5 Bxc2 25.Bg5 Qb4 26.b3 Bxg5 27.Qxg5 Re8 28.h4 Qf8 29.f6 g6 30.h5 Kh8 31.Rf3 Rd8 32.hxg6 Bxg6 33.Qxg6 1-0 9.6 Jan Sprenger 2508 Michal Luch 2414 Pardubice 2005 (6) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Bd3 Nc6 7.Nxc6 dxc6 8.0-0 e5 9.f4 Bc5+ 10.Kh1 Nf6 11.a4 11...Ng4 The start of an aggressive manoeuvre, but it ultimately loses time. A) 11...a5 12.Qf3 Qe7 13.f5 Bd7 14.Qg3 0-0-0 15.Be3²; B) 11...Qe7!? 12.Qe1 a5 (12...h5 13.f5 h4 14.Rf3 Nh5 15.Be3 Bxe3 16.Qxe3²) 13.f5² Black finds it hard to develop actively, as the natural 13...0-0?! encounters a mighty attack with 14.Qh4 h6 15.Bc4±. 12.Qf3 Qe7 13.f5 Qh4 14.h3 Nf2+ 15.Kh2 h5 15...Bd7 16.Bd2 Nxd3 17.Qxd3 suits White, due to Black’s passive d7-bishop. 16.Nd1² Nxd1 16...Ng4+ 17.Kh1 a5 at least keeps the tension. 17.Qxd1 Qe7 18.c3± a5 19.Bc4 Bd7 20.Qb3 Rb8 21.f6! Full marks for aesthetics! 21.Rd1 was the normal move. 21...gxf6 22.Bg5! fxg5 23.Rxf7 Qxf7?! Giving up too easily: 23...Qd6 24.Rd1 Bd4 25.cxd4 exd4+ 26.Kh1± 24.Bxf7+ Ke7 25.Rf1+–... 1-0 (34) 9.7 Ma Qun 2608 Li Shilong 2516 Zaozhuang 2015 (3) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Bd3 Nf6 6.0-0 Qc7 7.Nc3 d6 8.Kh1 8.Qe2 Be7 9.f4 0-0 10.Kh1 Nbd7 11.Bd2 8...Be7 9.f4 Nbd7 10.Bd2 0-0 11.Qe2 Nc5 12.b4 Nxd3 13.cxd3 13...e5! A) 13...Bd7 14.Rac1 Qb6 15.Nb3 Rfc8 16.a3 Qd8 17.Qf3! b6 (17...Bc6 18.Na5²) 18.Nd4 White’s space feels slightly more important than Black’s bishop pair, though I must admit that if Black plays perfectly he will equalise, a case in point being 18...h6 19.Be3 e5 20.fxe5 (20.Nde2!? keeps more fight in the position) 20...dxe5 21.Nf5 Bxf5 22.Qxf5 Qxd3! 23.Nd5 Nxd5 24.Rxc8+ Rxc8 25.Qxc8+ Bf8 26.exd5 Qxf1+ 27.Bg1 Qd3 28.d6 Qxd6 29.Qxa6 Qd7 30.Qxb6 e4 31.h3 f5!= and 0.00, but in a practical game all three results are possible; B) 13...b5 14.g4! e5 15.Nf5 Bxf5 16.gxf5² gives White a ready-made attack down the g-file; C) 13...Qd7 14.g4!’; 13...b6!? looks a bit risky after 14.g4 (14.Rac1 Qd7 15.Be3 Bb7 16.Nb3 Bd8=) 14...Bb7 15.g5 Nd7 16.Rac1 Qd8 17.a3 g6 18.h4² with a looming pawn storm. 14.Nc2 Bg4!? 14...exf4 15.Rxf4 Be6 16.Ne3 (Pitra-Gordon, Jakarta 2012; 16.Nd4 Nd7 17.Rc1 Qd8=) 16...Rac8 17.Raf1 Qd8 18.Nf5 Kh8² White has slight pressure, but Black is rock solid. 15.Qf2 d5 16.Ne3! dxe4 17.f5! A very creative idea, demanding an equally brilliant response from Black! 17...exd3? 17...Qc6! 18.Rac1 (18.Rfc1 exd3 19.Ncd5 Qxd5 20.Nxd5 Nxd5 21.Qg3 Bxf5 22.Qxe5 Be6 23.Qe4 Rad8°) 18...exd3 19.Ncd5 Qxd5 20.Nxd5 Nxd5 (two pieces and two pawns tend to be enough for a queen when the pieces can find safe posts) 21.Rfe1 Be2 22.Rxe2 dxe2 23.Qxe2 Bf6 and Black’s position is impregnable. 18.Ncd5 Nxd5 19.Nxd5 Qd6 20.Nxe7+ Qxe7 21.Qg3 f6 22.Qxg4± e4? A blunder, but in a piece down position, all moves are bad. 22...Rfd8 was better. 23.Rae1 Qf7 23...Rfe8 24.Rf4 24.Rxe4 Qxa2 25.Re7 Rf7 26.Rxf7 Kxf7 27.Qe4+–... 1-0 (36) 9.8 Gata Kamsky 2741 Shakhriyar Mamedyarov 2775 Tromsø 2013 (4) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 4...a6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Bd3 Nf6 7.0-0 Be7 8.Kh1 Nc6 9.Be3 d6 10.f4 Bd7 11.Qf3 0-0 12.Rae1 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.f4 d6 7.Be3 Nf6 8.Qf3 a6 9.Bd3 Be7 10.0-0 0-0 11.Kh1 Bd7 12.Rae1 12...b5 As we know, this is a prerequisite for Black’s counterplay. A) 12...e5? 13.Nxc6 bxc6 14.h3ƒ; B) 12...Nb4 13.g4! g6 14.f5 e5 15.Nde2 gxf5 16.gxf5 Kh8 17.Ng3²; C) 12...Nxd4?! 13.Bxd4 Bc6 14.Qh3 e5 15.fxe5 dxe5 16.Nd5 Bxd5 17.Bxe5 Qxe5 18.exd5 Qc7 19.Rxf6 g6 20.Rf2²; D) 12...Rac8 13.a3 g6 (13...Nxd4 14.Bxd4 Bc6 15.Qg3²) 14.Nxc6 Bxc6 15.Qh3ƒ tees up an f4-f5 break. 13.a3 13.g4 b4 14.Nce2 d5 15.e5 Nxd4 16.Nxd4 Ne4=; 13.Qg3!? b4! (13...Rae8 14.Nf3!?) 14.Nce2 Nxd4 15.Bxd4 Bc6 16.e5 Nh5 17.Qh3 g6 18.Ng3 Nxg3+ 19.hxg3 Bb5= 13...Rab8 Almost every move has been tried here, but not the strongest one: A) 13...Rae8!N This is very unnatural, but the rooks hold back all White’s attacking attempts: 14.Qg3 Nh5 15.Qf2 Nf6 White can repeat with 16.Qg3, but he doesn’t have anything better, e.g. 16.Nxc6 Bxc6 17.Qg3 Nd7 18.Bd4 e5 19.fxe5 Nxe5 and finally it is clear why the rooks are best on e8 and f8!; B) 13...Nxd4?! 14.Bxd4 Bc6 15.Qh3 g6 16.f5 e5 17.Be3±; C) 13...Rac8 14.Qg3 Rfe8 (14...Nh5 15.Qh3 Nxd4 16.Qxh5 g6 17.Qh3 Nc6 18.f5 with attack) 15.e5! Nh5 16.Qh3 g6 In Korneev-Valenti, Arco 2003, White should have sounded the charge with 17.g4 (or 17.f5!?) 17...dxe5 18.fxe5 Ng7 19.Ne4 Nxe5 20.Bf4² 14.Nxc6 14.Qg3! and e4-e5 was the right plan: 14...b4 15.Nxc6 Qxc6 16.axb4 Rxb4 17.Bc1² 14...Bxc6 15.Qh3 Rfd8? 15...e5 is the thematic reply to Qh3, stabilising the centre: 16.fxe5 dxe5 17.Bg5 Qd6! 18.Nd5 Bxd5 19.exd5 g6 20.Qh4 Nxd5 21.Bxe7 Nxe7 22.Rf6 Qc7 23.Rxa6 Rfd8= 15...Rbd8 is likewise met with 16.Bd4!. 16.Bd2 Preparing a wild sacrificial attack, but this is not the strongest: A) 16.e5 dxe5 17.fxe5 Qxe5 18.Bf4 Qh5 19.Qxh5 Nxh5 20.Bxb8 Rxb8°; B) 16.Bd4! e5 17.fxe5 dxe5 18.Nd5! was the way to show off: 18...Bxd5 19.Bxe5 Qxe5 20.exd5 Qxd5 21.Rxf6 Qxd3 22.cxd3 Bxf6 23.b4 Black can probably construct a fortress, but it’s not trivial. 16...d5! 17.e5 Ne4 18.f5! Nxd2 19.fxe6 Ne4 20.exf7+ Kh8 21.Nxd5! Bxd5 22.Rxe4 g6 23.Ref4 This move ultimately wins the game, but there’s a fly in the ointment! 23.Ree1 Rb6 24.e6 Kg7 is dynamically balanced. 23...Kg7? 23...Qb6! 24.Qh6 (24.Rf6? Bxf6 25.Rxf6 Qd4!–+ Perhaps this key move, preventing Bxg6, escaped Mamedyarov) 24...Rf8 25.Rf6 Bxf6 26.Bxg6 Rxf7 27.Bxf7 Bxf7 28.Rxf6 Qc7 – the bishop trumps the pawns now that the attack is over. 24.e6± Rf8 25.Qe3! Bc5 26.Qe1 Bd6? The obligatory 26...Be7 still doesn’t rain on White’s parade: 27.c4! bxc4 28.Qc3+ Kh6 29.Bxc4 Bxc4 30.Rxc4 Qd6 31.Rc6 Qd5 32.b4± and the advanced connected passers straitjacket Black. 27.Rh4+– Be7 28.Qe3! h5 28...Bxh4 29.Qd4+ Kh6 30.Qxh4+ Kg7 31.Qf6+ Kh6 32.Rf4 29.Qd4+ Kh6 30.Rxh5+ 1-0 30...Kxh5 31.Qxd5+ Kh6 32.Qe4 9.9 Zigurds Dauga 2454 Mark Adams 2260 ICCF email 2014 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Bd3 Nf6 7.0-0 d6 8.f4 Nbd7 9.Kh1 Be7 10.Qe2 b6 11.Bd2 Bb7 12.b4! 12.Rae1 Nc5 13.e5 dxe5 14.fxe5 Nfd7 gets wild, but the complications aren’t inferior for Black after 15.Qg4 Nxe5 16.Qg3 f6 17.b4 0-0-0! 18.bxc5 Rxd4 19.cxb6 Qd8!?= 12...0-0 A) 12...h5?! 13.Rae1 h4 14.Rf3! g6 15.Rh3²; B) 12...g6? 13.b5! axb5 14.Ncxb5 Qb8 15.e5 dxe5 16.fxe5 Nh5 17.Rxf7! Kxf7 18.Rf1+ Ke8 19.Nxe6+– PijpersMartens, Netherlands tt 2014/15. 13.Rae1 13.a4 g6! 13...Rfd8 A) 13...g6! seems to equalise if Black continues correctly: 14.b5 (14.e5 Ne8 15.exd6?! Nxd6!) 14...axb5 15.e5! (after 15.Ncxb5 Qd8 16.e5 Ne8 17.exd6 Bf6! 18.f5 exf5 19.Nxf5 gxf5 20.Bxf5 Ra4! 21.c4 Bg7 White’s attack doesn’t grant more than a draw) 15...Ne8 16.exd6 Nxd6 17.f5! Nc5 (Black’s position looks dangerous, but he is not at all worse) 18.fxe6 (18.f6 Bd8 19.Ndxb5 Nxb5 20.Bxb5 Nd7 can easily backfire on White as the f6-pawn is a target) 18...f5! 19.Ncxb5 Nxb5 20.Bxb5 Ne4 21.Bh6 Rfd8 22.Nxf5 gxf5 23.Rxf5 Ng3+ 24.hxg3 Qxg3 25.Kg1 Qg6 26.Rh5 Rxa2= Black has sufficient counterplay; B) 13...Ne8?! 14.Qg4 Nef6 15.Qh3² 14.a3! h6 15.Rf3! A thematic rook lift to menace Black’s king when g4-g5 is not so effective. 15...Nh7 15...b5 16.Rg3 Rac8 17.Nb3! with an attack. 16.Rg3 Bf6 17.Qf2 The engine gives equality, but suggests shuffling moves for Black, so I suspect his position is just inferior. 17...Kh8 17...Re8 18.a4!?ƒ 18.Rh3ƒ Rac8 19.Nce2 b5 20.Nf3 Kg8 A) 20...e5 21.Ng3 exf4 22.Bxf4 Bc3 It’s only here that the computer ‘wakes up’ and finds the combination 23.Bxh6! gxh6 24.Rxh6 Bxe1 25.Rxh7+! Kxh7 26.Ng5+ Kh8 27.Qf5 Nf6 28.Qxf6+ Kg8 29.Nf5 Bc3 30.Ne7+ Qxe7 31.Qxe7+–; B) 20...Be7 21.Ng5! 21.Ned4 Bxd4 22.Nxd4 Nhf6 22...Ndf6± was more tenacious. 23.Qh4! Kf8 24.Rg3 1-0 It might seem an untimely resignation, but on 24...Re8 25.e5! will quickly finish Black’s kingside defence. 9.10 Rui Gao 2533 Zhou Jianchao 2578 China 2015 (16) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Bd3 Nf6 7.f4 d6 8.0-0 b5 9.Qe2 Nbd7 10.Kh1 Bb7 11.Bd2 Be7 12.b4 0-0 13.a4 bxa4 14.Rxa4 14.Nxa4 was better. 14...Nb6 The automatic move, but it’s better to start with 14...Rfc8! as taking on a6 leaves White’s queenside vulnerable to attack: 15.Raa1 (15.Bxa6 Nb6 16.Ndb5 Bxa6 17.Rxa6 Qc4 18.Rxa8 Rxa8 19.Re1 d5 20.exd5 Qxe2 21.Rxe2 Nbxd5 22.Nxd5 Nxd5=; White can no longer retain his extra pawn) 15...g6 (15...Bf8!?) 16.Rae1 Bf8= 15.Raa1 15.Ra3!? may even be more accurate, intending 15...h6 16.Rfa1 d5 17.e5 Ne4 18.Be1 Rfd8 19.Rb3² with durable queenside pressure. 15...Rfc8? A) 15...d5? 16.e5 Ne4 17.Nxe4 dxe4 18.Bxe4 Bxe4 19.Qxe4±; B) 15...Nfd7!? 16.Bxa6 (16.Na4!? looks a touch better for White, but is virgin territory) 16...Rxa6 17.Rxa6 Bxa6 18.Qxa6 Rc8 19.Qd3 Nc4 20.Ndb5 Qb7° Potrata-Koch, email 2013. 16.e5! Nfd5 16...Nfd7 17.f5! Nxe5 18.fxe6± Mihok-Toth, Hungary 2009. 17.Nxd5 Bxd5 18.f5!+– The subsequent blows show why the Chinese players have long been reputed for their superb tactical vision. 18...dxe5 19.fxe6 Rf8 20.Bxh7+! Kxh7 21.Qh5+ Kg8 22.Rxf7 exd4 23.Bh6! Bg5 24.Rxc7 Bxh6 25.e7 Rfb8 26.Rf1 Re8 27.Qg6 Nc4 28.Rf5 Bxg2+ 29.Qxg2 Ne3 30.Qe4 Nxf5 31.Qxf5 Be3 32.Qd5+ Kh7 33.Rd7 1-0 9.11 Benjamin Bok 2458 Friso Nijboer 2583 Groningen 2010 (6) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Bd3 Nf6 7.0-0 d6 8.f4 b5 9.Qe2 Nbd7 10.Kh1 Bb7 11.Bd2 Be7 12.b4! 0-0 13.a4 bxa4 14.Rxa4 14.Nxa4!? Rfe8 15.Nc3 looks better. 14...Rfe8 15.Raa1 Automatic, but perhaps White should wait for ...Nb6: 15.Nb3!?N 15...Nb6 16.Raa1 d5 17.e5 Nfd7 18.Na4 Nxa4 19.Rxa4 Nb6 20.Ra2 Nc4 21.Rb1² I like White’s space, but Black can play too. 15...Bf8 16.Nb3 e5 16...d5? 17.e5 Bxb4 18.exf6 Bxc3 19.Bxh7+! Kxh7 20.Qd3+ Kg8 21.Bxc3± Rac8 22.Qg3 g6 23.Bd4 Qxc2 24.f5+– 17.fxe5 Nxe5 18.Na5 d5?! Black was probably afraid of Rxf6 sacrifices and panicked, but after 18...Rac8 I can’t see a trace of an edge for White: 19.Rxf6!? (19.h3 Ba8!? 20.Bxa6 Rb8°; 19.Nxb7 Nxd3 20.cxd3 Qxb7 21.Rxf6 gxf6 22.Qg4+ Kh8 23.Nd5 Bg7=; 19.Rac1 d5 20.Rxf6 Nxd3 21.cxd3 gxf6 22.Qf1 Qd7 23.Nxb7 dxe4 24.Nxe4 Rxe4 25.dxe4 Rxc1 26.Qxc1 Qxb7 is drawish) 19...Nxd3 20.cxd3 gxf6 21.Qg4+ Kh8 22.Nxb7 Qxb7 23.Nd5 Bg7 24.Qh4 Re6 25.Bc3 Rxc3! (25...Qb5 26.Rd1²) 26.Nxc3 Qxb4 27.Nd5 Qd4 Black’s queen is so active that the knight vs. bishop imbalance doesn’t come into play. 19.Nxb7 Neg4? Jumping out of the frying pan and into the fire. 19...d4 20.Nd5 Nxd5 21.exd5 Qxb7 22.Bxa6 Qxd5 retained material equality, but White retains the initiative with 23.Ra5 Qe6 24.Bb5 Red8 25.Re1 f6 26.Bd3². 20.Rf4+– Bxb4 21.Nxd5 Nxd5 22.Rxg4 Qxb7 23.Rb1 Qe7 24.Bg5 Qc5 25.Qf3 Nc7 26.e5 Ne6 27.Be3 1-0 9.12 Yuri Kryvoruchko 2612 Ilia Smirin 2630 Plovdiv 2008 (10) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Bd3 Bc5 7.Nb3 Be7 8.0-0 Nf6 9.f4 d6 10.e5 dxe5 11.fxe5 Qxe5 12.Bf4 Qh5 13.Be2 Qh4 14.g3 Qh3 15.Ne4 e5 16.Nd6+ Bxd6 17.Qxd6± Nbd7 A) 17...exf4 18.Rad1 Nfd7 loses in several ways. The flashiest is 19.Bh5! Nc6 20.Rfe1+ Kd8 21.Bxf7 fxg3 22.hxg3+–; B) 17...Nc6 18.Bxe5 Nxe5 19.Rae1 Be6 20.Nc5 Rd8 21.Qxe5 0-0 22.Nxe6 Qxe6 23.Qxe6 fxe6 24.Bc4 leaves Black a pawn down with the worse minor piece. 18.Rfe1 18.Rae1 18...Ne4 19.Qb4 f5 20.Bf3! If we’re counting material, how about Black’s on the back rank? 20...exf4 21.Bxe4 fxe4 22.Rxe4+ Kd8 22...Kf7 might lead to a fun king hunt: 23.Re7+ Kg6 24.Qe4+ Kh5 25.Rf1 fxg3 26.Qe2+ Kg6 27.Qd3+ Kh6 28.Qe3+ Kh5 29.hxg3+– 23.Rd1 Qh6 24.Rd6 1-0 9.13 Yaroslav Zinchenko 2544 Lucian Filip 2470 Paleochora 2010 (4) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Bd3 Nf6 7.0-0 Bc5 8.Nb3 Be7 9.f4 d6 10.e5 dxe5 11.fxe5 Nfd7 12.Qg4 g6 13.Bh6 13.Qg3! Nc6 (13...Nxe5 14.Bf4) 14.Bh6 Ncxe5?! 13...Nxe5 14.Qg3 Nbd7? 14...f5! 15.Rae1± Bf8 Exchanging pieces is probably the best try. A) 15...Rg8 16.Bf4 Qb6+ 17.Kh1 f6 18.Qh3+–; B) 15...Qb8 16.Kh1 f6 17.Nd4 piles central pressure on Black. 16.Bxf8 Kxf8? 16...Rxf8 17.Ne4 b5 18.Ng5 is also losing with best play, though. 17.Kh1 Kg7 18.Ne4+– Rf8 18...h6 19.Ned2! Qb8 20.Nc4 Nxd3 21.Qxd3+– 19.Ng5 Qd6 20.Nd4! b5 20...Qxd4 21.Rxf7+! Rxf7 22.Nxe6+ 21.Ndf3 21.Rd1! 21...Nc4? 21...h6 is necessary, even though it allows 22.Nxf7! Rxf7 23.Bxg6. 22.Qh4 h6 23.Nxe6+ 23.Bxg6! 23...fxe6 24.Qe4 e5 25.Qxa8 Ndb6 26.Qe4 Rf4 27.Qe2 Bb7 28.Bxc4 Nxc4 29.b3 e4 30.bxc4 exf3 31.Qe7+ Qxe7 32.Rxe7+ Rf7 33.Rxf7+ Kxf7 34.cxb5 1-0 Chapter 10 2...d6 sidelines 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 2...d6 is the dominant move at the top level, played with the intent of the Najdorf Sicilian, but first we’ll consider some rare black options. While it would have been funny to name the chapter ‘Fifth Move Mistakes’, even inferior moves should be taken seriously. 4...Nf6 Passive moves are well met with the Maroczy Bind (5.c4). 4...e5? before ...a7-a6 is a mistake because of 5.Bb5+! Bd7 (5...Nd7 6.Nf5 a6 7.Ba4 b5 8.Bb3 is going to transpose to 4...Nf6 5.Nc3 e5, e.g. 8...Nc5 9.Nc3 Nf6) 6.Bxd7+ Qxd7 7.Ne2! Qg4?! (7...Nf6 8.Nbc3 transposes to 4...Nf6 5.Nc3 e5) 8.Qd3! (Black is unable to take on g2 due to Rg1 and Qb5, so his queen move was a waste of time) 8...Nf6 9.Nbc3 and we’re back in 4...Nf6 territory. 5.Nc3 Rare fifth moves A) 5...h6?! looks a bit pointless with conventional play: 6.Be3 e5 7.Bb5+! Bd7 8.Bxd7+ Qxd7 9.Nde2²; B) 5...Nbd7 6.g4! h6 7.h4 is an improved Keres Attack for White, as after the coming g4-g5, Black will be unable to retreat to d7: 7...a6 (or 7...e6 8.Bg2ƒ and Black must already start playing unnatural moves to avoid the full sting of the g4-g5 break) 8.Rg1N 8...Nc5 9.Qe2± I have been unable to make sense of Black’s set-up. If he tries to hit in the centre with 9...d5, 10.exd5 Nxd5 11.Nxd5 Qxd5 12.Be3 and Bg2 gives White a sizeable lead in development; C) 5...e5? 6.Bb5+! C1) 6...Bd7 7.Bxd7+ Qxd7 8.Nde2 One could stop here as White has an obvious positional advantage, but it’s worth studying the games Vorobiov-Kamber, Zurich 2015, and Berg-Becker, Germany Bundesliga 2014/15: 8...Qc6 9.Ng3 Nbd7 10.Bg5 g6 11.Qd3 Be7 12.0-0-0 and with Bxf6 and Nf1-e3-d5 to follow, White has an obvious positional superiority; C2) 6...Nbd7 7.Nf5 a6 8.Ba4 b5 9.Bb3 Nc5 (9...Nb6 10.Bg5 Bxf5 11.exf5 Be7 12.Bxf6 Bxf6 13.Qg4!N 13...0-0 14.0-0 Qe7 15.Rfd1± and a2-a4 is quite a depressing position for Black) 10.Bg5 Bxf5 (10...Bb7?! 11.Bd5!±) 11.exf5 Be7 12.00 0-0 13.Bxf6 Bxf6 14.Nd5 e4 15.c3 White has full control of the position with the better minor pieces, Gopal-Nagy, Pardubice 2016. The Kupreichik Variation 5...Bd7 This Kupreichik Variation was recently played by Carlsen in blitz, but the English Attack set-up works well against this and other sidelines. 6.f3!? This will transpose to good versions of the English Attack against the Najdorf/Scheveningen. 6...e5 6...Nc6 7.Be3 e6 8.Qd2ƒ transposes to the Scheveningen, where Black has committed the bishop to d7 too early (as will become clear after g4-g5). 7.Nb3 Be7 7...Bc6 8.Be3 Be7 9.Qd2 0-0 10.0-0-0 is unconvincing as the bishop serves little purpose on c6: 10...a5 11.a4 Na6 12.g4 Nb4 13.Kb1N 13...Qd7 14.g5 Ne8 15.h4! Now ...Bxa4 gets hit by Nc5, but 15...Nc7 16.h5 Bxa4 17.g6! with a monstrous attack isn’t much better. 8.Be3 0-0 8...Be6 is the engine’s first choice, but then it’s just a Najdorf without ...a7-a6, which is hardly enticing. 9.Qd2 a5 This is the only way to justify Black’s play, but the ...a7-a5 Najdorf variation is so weak that even the extra tempo ...Bd7 doesn’t really help Black’s case. 10.a4! Na6 10...Nc6 11.0-0-0 Be6 will come to the same thing after a later ...Nb4. 11.0-0-0 Nb4 12.g4 Be6 This is the best move, transposing to the 10...a5 Najdorf. 12...Qc7 13.Kb1 Rfc8 is one independent attempt, but 14.h4 d5 (a bit desperate, but otherwise h4-h5/g4-g5-g6 will hurt) 15.exd5 Nfxd5 16.Nxd5 Nxd5 17.Qxd5 Qxc2+ 18.Ka2 Bc6 19.Qd3 Bxf3 20.Rc1 Qxd3 21.Bxd3 Bxh1 22.Rxh1 just doesn’t work for Black. 13.Kb1 Since the structure is stable, the best approach is to remember some key games. 13...Rc8 Black’s alternatives are covered in Nimtz-Soltau, email 2007. 14.g5 Nh5 14...Nd7± is worse, as shown in Saric-Shirov, Reykjavik 2015. 15.Rg1!± This line is virtually refuted, see Iotov-Novak, email 2012. Summary 2...d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3: 5...Nbd7 – +0.40 5...e5 – +0.50 5...Bd7 – +0.50 10.1 Evgeny Vorobiov 2574 Kamber 2295 Zurich 2015 (2) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 Nf6 4.Nc3 cxd4 5.Nxd4 e5 6.Bb5+ Bd7 7.Bxd7+ Qxd7 8.Nde2 h6 9.Be3 Qc6 10.f3 Nbd7 11.Qd3 a6 12.0-0-0± Black is several tempi behind on the English Attack, and White has already traded his bad bishop for Black’s good bishop. 12...Be7 12...h5 13.h3 h4 14.Kb1 b5 15.Nd5 Nxd5 16.Qxd5 Qxd5 17.Rxd5± 13.g4 b5 14.Ng3 14.Kb1!? 14...g6 14...b4 15.Nce2 Nc5 16.Qd2 b3 is only momentary counterplay after 17.Kb1 bxa2+ 18.Ka1!± and the black a2-pawn is the perfect shield! 15.h4 Nc5 16.Bxc5 Qxc5 17.h5± Black’s kingside pawns look tender now. 17...Rc8 17...Qc4 18.Qxc4 bxc4 18.hxg6 fxg6 19.Kb1 Now Black can connect his rooks. More direct is 19.g5! Ng8 20.gxh6 Rxh6 21.Rxh6 Nxh6 22.Kb1± and Nd5 is highly disagreeable. 19...Kf7! 20.Qd2 20.a3!? 20...Rh7? 20...a5 would distract White from his kingside agenda. 21.Nf1 21.Rh2 was better. 21...Kg7 22.Ne3 Kh8? 22...Nd7² prevents the next move. 23.g5! hxg5 23...Nh5 24.gxh6 Bg5 24.Rxh7+ Kxh7 25.Ncd5+– Nxd5 26.Nxd5 Bf8 27.c3 Bg7 28.Rh1+ Kg8 29.Ne7+ Kf7 30.Nxc8 Qxc8 31.Qxd6 g4 32.Qd5+ Ke7 33.Rh7 Kf6 34.Qd6+ Qe6 35.Qxe6+ Kxe6 36.fxg4 1-0 10.2 Emanuel Berg 2555 Michael Becker 2321 Germany Bundesliga 2014/15 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Bb5+ Bd7 7.Bxd7+ Qxd7 8.Nde2 Qg4?! 9.Qd3 Qxg2 A consistent but unsound pawn grab. 9...Nbd7 10.h3 Qe6 11.Be3± 10.Rg1 Qxh2 11.Bg5! Nbd7 12.Bxf6 gxf6?! 12...Nxf6 13.Qb5+ Nd7 14.Qxb7 Rb8 15.Qc6!+– scores 5/5 in correspondence, including some entertaining miniatures. 13.Qf3 13.Nd5!? may be even more clinical, though Black can hardly develop in any case. 13...Qh6 14.Rh1 Qg7 15.Rg1 Qh6 16.Rh1 Qg7 17.Nd5! Rc8 18.0-0-0+– h5 19.Ng3 Rg8 20.Nxh5 Qg5+ 21.Kb1 Be7 22.Ng3 Rc6 23.Nf5 Bd8 24.Nb4 Rb6 25.Nxd6+ Rxd6 26.Rxd6 Be7 27.Rdd1 Bxb4 28.Qd3 1-0 10.3 Geetha Narayanan Gopal 2565 Gabor Nagy 2439 Pardubice 2016 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Bb5+ Nbd7 7.Nf5 a6 8.Ba4 b5 9.Bb3 Nc5 10.Bg5 Bxf5 11.exf5 Be7 12.0-0 0-0 13.Bxf6 Bxf6 14.Nd5 e4 15.c3 15...Nd3?! The knight is easily evicted from d3. A) 15...a5 16.Qg4!? b4 17.cxb4 axb4 18.Rab1 Nxb3 19.axb3ƒ; B) 15...Re8 16.Bc2 Re5 17.Re1 Rc8 18.g3 h5 19.h4 Rxf5 20.Bxe4 Nxe4 21.Rxe4² was Jäderholm-Bobrov, email 2008, where White has the better minor piece and structure, but nothing is decided yet. 16.Qe2 16.Rb1 16...Re8 17.a4?! This is too early while the knight sits on d3. 17.Rab1; 17.g3± 17...Rb8! 18.Ra2 Re5? A curious decision. 18...bxa4 19.Bxa4 Re5= 19.axb5 Nc5?! 19...Rxb5 20.Nxf6+ Qxf6 21.Bc4 Rb8 22.Bxd3 exd3 23.Qxd3 wins a pawn, but the game continues. 20.Nxf6+ 20.Nb4!+– 20...Qxf6 21.Bc2 axb5 22.Qxb5 Ree8 Now the game takes some curious turns. 23.Qc6?! 23.Qc4 Qxf5 24.f3± 23...Qxf5 24.Qxd6 Rbd8 24...Nd3!= 25.Qc6 Nd3 26.Ra4 Rc8 27.Qd6 Rcd8 27...Nxb2 28.Qc6 h5?! 28...Rc8= 29.Rd4 29.Qb6!² 29...Rxd4?? As one of my students often says, he who makes the second to last mistake wins. 29...Rc8° 30.Qxe8+ Kh7 31.cxd4 1-0 10.3 Manfred Nimtz 2641 Achim Soltau 2624 ICCF email 2007 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 5...Bd7 6.f3 (6.h3!? e5 7.Nde2 Bc6 8.Ng3²) 6...e5 7.Nb3 Be7 8.Be3 0-0 9.Qd2 a5 10.a4 would be our move order. 6.Be3 e5 7.Nb3 Be6 8.f3 Be7 9.Qd2 0-0 10.0-0-0 a5 11.a4 Nc6 12.g4 Nb4 13.Kb1 13...Qc7 A) 13...d5 loses a pawn: 14.g5 Nxe4 15.fxe4 d4 16.Qg2 Qc8 17.Nxd4 exd4 18.Bxd4 Rd8 19.Rd2 Bc5 20.Bxc5 Qxc5 21.Bb5± Kireev-Szymanski, email 2012; B) 13...Nd7 14.h4 (14.Bb5!?±) 14...Nb6 15.Qf2 Nc4 16.Bxc4 Bxc4 17.Bb6 Qd7 18.Bxa5 Bxb3 19.Bxb4 Bxa4 20.Nd5 gives White domination across the board: 20...Ra6 21.b3 Bb5 22.g5 Rfa8 23.Bc3 b6 24.Bb2 (White has scored 4/4 in email games here) 24...Bc6 25.Nb4 Ra5 26.Qxb6 Bb7 27.Nd5 Bxd5 28.Rxd5 Rxd5 29.exd5 Qf5 30.Qe3 JacewiczKürten, email 2011. 14.g5 Nh5 15.Rg1! A useful prophylaxis against ...f7-f5. 15.Bb5 15...d5 A) 15...Rac8 transposes to 13...Rc8; B) 15...g6 16.Qf2 Qc6 17.h4 f5 18.gxf6 Nxf6 19.Bb5 Qc8 20.Bh6 Rf7 21.Qb6 Kh8 22.Rg2 and Black could not free his position in Pierzak-Mende, email 2011. 16.Nxd5 Nxd5 17.exd5 Bxd5 18.Qxd5! Rad8 19.Bb5 Rxd5 20.Rxd5 Rd8 21.Rgd1 Rxd5 22.Rxd5 The queen sac is very strong because White’s pieces harmonise beautifully against the queen. 22...Bd6 23.Nxa5 Nf4 24.Bxf4 Qxa5 24...exf4 25.Nc4 Bf8 26.a5± 25.Bd2 Qc7 26.a5+– The queenside majority will end Black’s resistance. 26...f5 27.gxf6 gxf6 28.Bd3 Qc6 29.c4 Bf8 30.b3 Qe6 31.Bc3 Qh3 32.Rd8 Kf7 33.Be4 Qf1+ 34.Kb2 b5 35.a6 bxc4 36.Rd7+ Ke6 37.a7 Qf2+ 38.Kb1 Qf1+ 39.Kc2 cxb3+ 40.Kb2 Black resigned. 10.4 Ivan Saric 2652 Alexei Shirov 2689 Reykjavik 2015 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 e5 7.Nb3 Be6 8.f3 Be7 9.Qd2 0-0 10.0-0-0 a5 11.a4 Nc6 12.Kb1 Nb4 13.g4 Rc8 14.g5 Nd7 After 14...Ne8 15.f4 exf4 16.Bxf4 Bg4 17.Re1 Nc7 18.h4 Ne6 19.Be3 Bf3 20.Rh3 Bh5 21.Be2 Bxe2 22.Qxe2 Black faces a strong initiative. 15.f4 exf4 16.Bxf4 Bxb3 A) 16...Nc5 17.Nxc5 Rxc5 18.h4 Bg4 19.Be2 Bxe2 20.Qxe2 Qd7 21.Be3 Rcc8 22.Bd4 Qe6 23.Rhf1± White’s flank attack is always faster in this structure, Firsching-Böhnke, email 2013; B) 16...Ne5 17.h4 Qb6 18.Nd4 Bg4 19.Rc1± 17.cxb3 Ne5 18.h4 f6 19.Bh3 Rc6?! 19...Rb8 20.Nb5+– 20.Qe2!+– Qe8 20...Kh8 21.h5 21.Bxe5 fxe5 22.Rhf1 The difference between the bishops means Black’s game is in its last throes. 22...Kh8 23.Rxf8+ 23.Qb5 23...Qxf8 24.Rf1 Qd8 25.Qf3 g6 26.Be6 Rc7 27.Nb5 Rc2 28.h5 Bxg5 29.hxg6 Bf4 30.Qh5 Rh2 31.g7+ Kxg7 32.Rg1+ Kh8 33.Nxd6 1-0 10.5 Valentin Iotov 2542 Joze Novak 2508 ICCF email 2012 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 Ng4 7.Bc1 Nf6 8.f3 e5 9.Nb3 Be6 10.Be3 Be7 11.Qd2 0-0 12.0-0-0 a5 13.a4 Nc6 14.g4 Nb4 15.Kb1 Rc8 16.g5 Nh5 17.Rg1± 17...g6 A) 17...d5 18.exd5 Bf5 19.Na1 looks passive, but Black can’t break White’s solid position: 19...Bc5 (19...Qd6 20.Ne4 Qg6 21.d6! Qe6 22.b3 Rfd8 23.Bc5±) 20.Bb5 Nf4 21.Bxf4!? Bxg1 22.Bxe5 Qb6 23.Bf4+– White has positional domination; B) After 17...Qc7 18.Qf2 Black has a choice but in all cases his weak queenside factors in: B1) 18...Bd8 19.Nc1! f5 20.Qd2 fxe4 21.fxe4 (Schlenther-Konstantinov, email 2013) 21...Be7 22.Nd3 Nxd3 23.Bxd3 Nf4 24.Bb5±; B2) 18...Nf4 19.Bxf4 exf4 20.Nd4 leaves Black weak on the light squares: 20...d5 (20...Qb6 21.Rg2 Rfd8 22.Nxe6 Qxf2 23.Rxf2 fxe6 24.h4± Zhigalko-Kadric, Aix-les-Bains 2011) 21.Nxe6 fxe6 22.Bh3 Kh8 23.Bxe6 Bc5 24.Qg2 Bxg1 25.Bxc8 Rxc8 26.Qxg1 dxe4 27.fxe4²; B3) 18...f5 19.Bb6 Qb8 20.Qe2 Nf4 21.Qb5 fxe4 22.fxe4 d5 Black held a draw in a correspondence game, but I found an improvement: 23.exd5!N 23...Bf5 24.Rd2 Qd6 25.Bxa5 Nxc2 26.Rxc2 Qg6 27.Na1 Bc5 28.Rg3 b6 29.Bb4 Nh5 30.Bxc5 Rxc5 31.Qe2 Nxg3 32.hxg3 Qxg5 33.Bg2 Qxg3 34.Be4± At the end of the complications, the two knights trump the rook and pawn; C) 17...f5 18.gxf6 Rxf6 19.Bg5 Rxf3 20.Bxe7 Qxe7 21.Qxd6 Qxd6 22.Rxd6 Bxb3 23.cxb3± (the bishop will be a monster from c4, plus Black’s pawns are mostly weak) 23...Nf6 (23...Nf4 24.Bc4+ Kh8 25.Rd7±; 23...Rf2 24.Bc4+ Kh8 25.Rd7 Rxh2 26.Nb5!±) 24.Bc4+ Kf8 25.Rb6 Rb8 26.Rb5 Nc6 27.Rd1 Re3 28.Bd5! Nxd5 29.exd5 Nd4 30.Rxa5 Nxb3 31.Rb5 Nd4 32.Rb6 h6 33.Rg1 Rf3 34.Re1 Rf6 35.d6 Nc6 36.Ne4 Rf4 37.Nc5+– Glorstad-Craig, email 2012. 18.Bb5 Qc7 19.Qf2! Once again forcing Black to go passive if he wants to save the a5-pawn. 19...Bd8 A) 19...f5 20.Bb6 Qb8 21.Qd2 Nf4 22.Bxa5 Na6 23.h4± Blank-Klimakovs, email 2012; B) 19...Nf4 20.Bxf4 exf4 21.h4 Bxb3 22.cxb3 d5 23.exd5 Bc5 24.Qe1 Bxg1 25.d6 Qb6 26.Qxg1 Qxg1 27.Rxg1± was a monster d-pawn for White in Schnabel-Kahl, email 2013. 20.Nc1! With Black tied up, the key is to maintain control. 20.h4 f5!? 20...f6 20...f5 21.Qd2 Be7 22.Nd3 fxe4 23.fxe4 Nxd3 24.Bxd3 Nf4 25.Bb5± 21.h4 fxg5 22.hxg5± Qe7 23.Rd2 Nf4 24.Rh1 Black has weaknesses on both flanks and can’t practically hope to hold this position. 24...Qf7 24...Bc7 25.N1e2 Nh5 26.Ng3 Nf4 27.Qh2± 25.Bxf4 exf4 26.Rhd1 Be7 27.Qb6 Nc6 28.Bxc6! bxc6 29.N1e2! Rb8 30.Qxc6 Rfc8 31.Qa6 Bc4 32.Nb5 Bxe2 33.Rxe2 Qc4 34.Rh2 Qxa4 35.Rd5+– Bf8 36.c3 Qc4 37.Qa7 h5 38.Qd7 Kh8 39.Nxd6 Bxd6 40.Qxd6 Qxc3 41.Qf6+ Qxf6 42.gxf6 Rf8 43.e5 Kg8 44.Re2 Rbe8 45.Re4 Kh7 46.Rxf4 And White won on the 79th move. Chapter 11 The Scheveningen 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e6 Part 1 – The ...Nc6 Scheveningen 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 d6 is a move order sometimes employed to avoid the Keres Attack. 6.Be3 Nf6 7.Qe2!? Negi recommends 7.f4 and then 8.Qe2, but I like it immediately, as Black’s best replies give White good versions of English Attack positions. A) 7...e5 8.Nb3 (the extra move Qe2 helps White develop his initiative) 8...Ng4 (8...Be7 9.0-0-0 0-0 10.f3 makes it hard for Black to develop because of Nc5, which also features after 10...a5 11.a3! a4 12.Nc5±) 9.0-0-0!N 9...Nxe3 10.Qxe3 Be7 11.Kb1 0-0 12.g3 and White has a much-improved version of the 6.Be3 e5 Najdorf, with f2-f4 coming up. 12...a5 fails to offer real counterplay in light of 13.Nc1!? a4 14.a3²; B) 7...Be7 8.0-0-0 0-0 9.g4! is White’s dream set-up, where delaying f2-f4 deprives Black of ...e6-e5 counterplay: 9...a6 (9...Nxd4 10.Bxd4 Nxg4 clearly fails to 11.Bxg7 Kxg7 12.Qxg4+ Kh8 13.Qh5! with a big attack) 10.g5 Nxd4 11.Bxd4 Nd7 12.h4 b5 13.a3 (it feels like we’re a tempo up on the 6.h3 Najdorf!) 13...Rb8 (or 13...Bb7 14.f4 Qa5 15.Bh3! b4 16.axb4 Qxb4 17.Nd5!±) 14.f4 Qa5 (14...b4 15.axb4 Rxb4 16.f5!±) 15.Qe1!ƒ This stops ...b5-b4 because of Na2. Now White can continue his attack uninterrupted; C) 7...Nxd4 8.Bxd4 e5 9.Be3 a6 10.0-0-0 Be6 11.f3 (White simply has an improved English Attack due to Black’s time-consuming play) 11...Rc8 (11...h5 12.Kb1 Be7 13.Qe1! Rc8 14.f4 exf4 15.Bxf4² makes ...h7-h5 look a bit loosening) 12.Qe1N 12...b5 13.Kb1 h5 (a sad necessity as g4-g5 would prove quite strong) 14.f4 Qc7 15.Bd3 Be7 16.a3 Qb7 17.f5 Bd7 18.Bg5, and White will occupy d5 with a serious positional advantage; D) 7...a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 (other moves are no better: 8...Be7 9.g4 h5 10.gxh5 Nxh5 11.Rg1ƒ is a much-improved version of the old Keres main line, since we didn’t need to play h2-h4; 8...Qc7 9.g4 Nxd4 10.Rxd4 b5 11.g5 Nd7 12.f4 Rb8 13.a3N 13...Be7 14.Rg1± is also familiar) 9.f4 Rc8 10.Kb1 Qc7 11.Nb3! b5 12.g4 b4 13.Na4 and White was dominating across the board in Ivanchuk-Van Wely, Wijk aan Zee 2015. Part 2 – The pure Scheveningen (Keres Attack) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e6 This is the ‘pure’ Scheveningen, which is under a cloud because of the Keres Attack: 6.g4! 6.Be3 is the practical approach, as Black’s attempts to play without ...a7-a6 leave him worse, but why not take the maximum advantage we can? 6...h6 Other moves give White a turbo-charged English Attack with g4-g5/Be3/h2-h4, while... A) 6...e5 7.Bb5+ Bd7 8.Bxd7+ Qxd7 9.Nf5 h5 10.Bg5! Nh7 11.f4! proved favourable for White in Wagner-Atlas, Austria tt 2016/17. A possible improvement is 11...hxg4!?N 12.Nd5 Nxg5 13.fxg5 Na6 14.Qxg4 0-0-0, but White maintains his light-square domination by keeping the pieces on: 15.Qg2! g6 16.Nfe3²; B) 6...d5? doesn’t work because of 7.exd5 Nxd5 8.Bb5+! Bd7 9.Nxd5 exd5 10.Qe2+ Qe7 11.Be3±. 7.Rg1! This flexible approach was advocated by Kotronias/Semkov, but the line remains relatively unexplored. 7...Nc6 A) 7...e5?! 8.Nb3 is an improved English Attack for White; B) 7...Be7 8.Be3 a6 9.Qf3! in turn reminds a bit of the 7.Qf3 Taimanov, and after 9...Nbd7 10.0-0-0 Qc7 11.Qh3!?ƒ, threatening 12.g5, Black comes to regret ...h7-h6 (11.h4 is just as good). 8.Be3 The usual moves with h2-h4 in place of Be3 don’t work here. 8...a6 A) The opening of the kingside with 8...h5?! 9.h3! hxg4 10.hxg4 favours White; B) 8...d5? is the main move after 8.h4, but now it looks silly: 9.exd5 Nxd5 10.Nxd5 Qxd5 11.Nb5!N 11...Qe5 12.Qd2±; C) In the case of 8...Bd7 9.Be2! (9.f4 is a bit early because of 9...e5!) 9...Be7 10.Qd2 Nxd4 11.Qxd4 Bc6 12.0-0-0 White’s set-up is an improved English Attack, with Be2 in place of f2-f3: 12...Qb6 13.Qc4 Qa5 14.h4! with g4-g5 and a strong initiative coming; D) 8...Be7 9.Qe2!? (like Negi, I find the queen is often well placed on e2 for supporting the kingside pawn storm. 9.Qf3 Bd7 10.0-0-0 Rc8 is less clear) 9...Nxd4 (9...a6 10.0-0-0 Qc7 11.f4± and h2-h4/g4-g5 shows that Black can’t settle for routine play) 10.Bxd4 e5 11.Be3 Be6 (11...Bd7 12.h4! and g4-g5 is unpleasant) 12.0-0-0 Rc8 (if 12...Nd7 13.Nb5!) 13.Qb5+ Qd7 (13...Nd7!? 14.Qxb7 0-0 15.Nd5 Bg5 16.Kb1² doesn’t give Black full compensation for the pawn) 14.Bxa7N 14...Bxg4 15.Qxd7+ Bxd7 16.f3 White has a stable endgame edge due to Black’s queenside weaknesses. 9.h4! Once Black has spent a tempo on ...a7-a6, there’s no reason to delay the pawn storm, otherwise ...Nxd4/...e6-e5 can be awkward. 9...h5 Releasing the tension with 9...Nxd4?! 10.Qxd4 e5 11.Qd1!± helps White. 10.gxh5 Nxh5 10...Rxh5 11.Bg5 Qb6? is creative but fails to impress: 12.Bxf6 gxf6 13.Nxc6 bxc6 14.Qxh5 Qxb2 15.Rb1 Qxc3+ 16.Kd1 Ke7 17.Bd3 c5 18.Rg3! and White has too much activity. 11.Nxc6! bxc6 12.Qd2ƒ This is an extremely tough position for Black, as he has minimal development and his king cannot find safety. 12...e5 A) 12...Nf6 13.0-0-0 Qc7 14.Bf4 e5 15.Bg5 Be6 16.f4 gave White a strong initiative in Lokander-Lindberg, Växjö 2017. 16...Qa5 attempts to improve on Black’s play, but then 17.Rg3!? exf4 18.Rd3 with intent of Bxf4 and Bxd6 is effective; B) 12...Qa5 13.0-0-0 Nf6 is Kotronias’s sample line, but White has a lot of good replies. I particularly like 14.Kb1!? Rb8 15.Bc4ƒ, sacking a pawn for a huge initiative. After Bb3, we might even play f2-f4 in one go. 13.Bc4!N It is important to stop ...Be6. 13...Rb8 14.0-0-0 I can’t see a good plan for Black. White has a clear advantage. 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Summary: 2...e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 d6 6.Be3 Nf6 – +0.45 2...d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e6 6.g4: 6...e5 – +0.35 6...h6 – +0.50 11.1 Vasily Ivanchuk 2715 Loek van Wely 2667 Wijk aan Zee 2015 (3) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 d6 6.Be3 Nf6 7.Qe2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f4 Rc8 10.Kb1 Qc7 11.Nb3 b5 12.g4 b4 13.Na4± e5?! This can be met in many good ways, but Ivanchuk’s answer is the most attractive! A) 13...Nxe4? 14.Bb6; B) 13...Rb8 is probably best, but the fire keeps burning after 14.e5! dxe5 15.Nac5 Bxc5 16.Bxc5!± with numerous threats. 14.g5! Bg4 15.Qg2 Bxd1 16.Bxa6 Nd7 A) 16...Ra8 17.Bb6 Qd7 18.Bb5+– is a deadly pin; B) 16...Ng4 17.Bb6 17.Rxd1 17.Bxc8 Qxc8 18.Rxd1 Qa6 19.Qh3! Qxa4 20.Qxd7+ Kxd7 21.Nc5+ Ke8 22.Nxa4± 17...Ra8 17...Rb8 at least keeps White’s pieces out. 18.Bb5 Be7 19.f5?! 19.fxe5 dxe5 20.Qh3+– 19...Qb7? 19...0-0± 20.c4+– White’s attack now progresses without a hitch. 20...0-0 21.f6 Bd8 22.Rxd6 Ncb8 23.Qg4 g6 24.h4 24.Bxd7 is a free piece, but Ivanchuk prefers to win with an attack. 24...h5 25.Qf3 Bc7 26.Rxd7 Nxd7 27.Bxd7 Rad8 28.Nbc5 Qa8 29.Qd1 Qa7 30.Qd5 Ra8 31.Bd2 Rfd8 32.Bxb4 Ba5 33.a3 Qc7 34.Nc3 Bxb4 35.axb4 Qa7 36.Kc2 Rac8 37.Nb5 Qa1 38.Nd6 Black resigned. 11.2 Dennis Wagner 2543 Valeri Atlas 2435 Austria tt 2016 (4) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e6 6.g4 e5 7.Bb5+ Bd7 8.Bxd7+ Qxd7 9.Nf5 h5 10.Bg5 Nh7 11.f4² g6 12.Ne3 Nxg5 13.fxg5 13...Be7 In the mildly amusing variation 13...hxg4!? 14.Ncd5 Be7 15.Nxg4 Kf8 16.Nxe7 Qxe7 17.h4 Qxg5 18.Qxd6+ Qe7 19.Qxe5 Qxe5 20.Nxe5 Rh5 21.Nf3 Nc6 Black has very good drawing chances with White’s kingside pawns isolated, but obviously White is pressing. 14.h4 hxg4 15.Kf2 Nc6 After 15...Na6 16.Qxg4 Qxg4 17.Nxg4 Rc8 18.Ne3² Black still has a bad bishop, but his pawn weaknesses are covered. 16.Ncd5 0-0-0?! 16...Nd4 was better. 17.Qxg4 Rdf8 18.Qxd7+ Kxd7 19.Ng4± Bd8 19...Nd4 20.c3 Ne6 20.Rad1 Ke6 21.Kg3 Ne7 22.Nc3 22.Ndf6!? Ng8 23.Rhf1 Nxf6 24.Nxf6± was a more active approach, immobilising the rooks. 22...Nc8 22...Nc6 23.Rhf1 a6?! Black continues to play too defensively. 23...f5 24.gxf6 Bxf6 25.Rxf6+ Rxf6 26.Nxf6 Kxf6 27.Nd5+ Kg7 28.Rd3!± 24.Nd5 Na7 25.Rd3+– Nc6 26.c3 Na5 27.Rfd1 Nc6 28.a4 Na7 29.b4 Nc8 30.c4 a5 31.bxa5 Bxa5 32.Rb1 f5 33.gxf6 Rf7 34.Nf2 Rfh7 35.Nh3 Rxh4 36.Ng5+ Kd7 37.f7 Bd8 38.f8=Q Rxf8 39.Kxh4 Rf2 40.Kg3 Rc2 41.Rxb7+ Kc6 42.Rc7+ Bxc7 43.Nb4+ Kc5 44.Nxc2 Kxc4 45.Rd1 Ba5 46.Nf7 Kb3 47.Ne3 1-0 11.3 Martin Lokander 2329 Henrik Lindberg 2214 Växjö 2017 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 d6 6.g4 h6 7.Rg1 Nc6 8.Be3 a6 9.h4 9...h5 10.gxh5 Nxh5 11.Nxc6 bxc6 12.Qd2 Nf6 13.0-0-0 Qc7 14.Bf4 e5 15.Bg5 Be6 16.f4ƒ exf4 16...Rb8 17.b3± 17.Bxf4 17.Be2! could be played first, completing development and keeping White’s options open. 17...Rxh4 18.Be2 18.Bxd6 Bxd6 19.Qxd6 Qxd6 20.Rxd6 Nxe4 21.Nxe4 Rxe4 22.Bd3 Rh4 23.Rxg7 offers endgame activity. 18...Nd7! 19.Rh1 19.Bxd6 Qxd6 20.Qxd6 Bxd6 21.Rxd6 Ne5 22.Rxg7 Ke7 23.Rd1 Ng6= 19...Rxh1 20.Rxh1 Ne5 21.Rh8? 21.Na4= 21...Rd8 21...Ng6! would force an unsound exchange sacrifice: 22.Bxd6 Qa7 23.Rxf8+ Nxf8, and Black may take over. 22.Bg5 f6 22...Rb8 avoids compromising the pawn structure. 23.Be3 Qa5 24.Qd4 c5 25.Qd1 Better was 25.Qd2. 25...Kd7?! The planned king manoeuvre proves suicidal, whereas 25...Bxa2! was a safe pawn snatch. 26.a3 Kc8? 26...Rb8 27.Nd5 Kc6= 27.Rxf8! Rxf8 28.Qxd6 Re8 29.Bxa6+ 1-0 Chapter 12 The Dragon 5...g6 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 The Dragon is quite popular among young players, not only for its cool name, but particularly the dynamic potential offered by the fianchetto. Therefore, it’s pivotal for White to play incisively, but I’m confident in our chances to obtain an advantage with correct play. 6.Be3 Bg7 A) 6...Ng4?? 7.Bb5+ Bd7 8.Qxg4 is a schoolboy trap; B) 6...a6 7.f3 b5 8.Qd2 Bb7 If Black plays ...Bg7 here or on the previous move, it will transpose to 6...Bg7. 9.a4! (a familiar theme from the Paulsen chapters. 9.g4!? scores even better, see the model game Giri-Ivanisevic, Doha 2014) 9...e5 (9...b4 10.Na2 e5 11.Nb3 transposes, whereas 9...bxa4?! 10.Nxa4 Nbd7 11.Nb3± and Na5 was miserable in Taher-Londok, Yogyakarta Istemuwa 2016) 10.Nb3 b4 11.Na2 d5 12.Bg5! (Black has tactical problems everywhere) 12...Nbd7 (or 12...h6 13.Bxf6 Qxf6 14.Nxb4! dxe4 15.Nd5±) 13.exd5 Bxd5 14.0-0-0N (14.Qxd5 Nxd5 15.Bxd8 Kxd8 16.0-0-0± as in Sax-Goh Wei Ming, Kecskemet 2011, is just as strong – Black really struggles to deal with the light-square pressure) 14...Qb6 15.Kb1± Black is unable to get his pieces out. The Dragadorf 7.f3 a6 8.Qd2 This is the ‘proper’ position for the Dragadorf, where Black has a few move orders but nothing unpleasant: A) 8...b5?! is thematically answered by 9.a4! b4 10.Na2 a5 11.Bb5+ Bd7 (11...Nbd7 12.c3 bxc3 13.Nxc3 Bb7 14.0-0 00 15.Nb3! Ne5 16.Rac1 places Black under heavy queenside pressure; the weak a5-pawn ties him down) 12.c3 bxc3 13.Nxc3 0-0 14.0-0 Black must make concessions to develop his queenside, e.g. 14...Na6 15.Nc6 Bxc6 16.Bxc6 Rb8 (Horak-Deschamp, email 2000) 17.Bb5 Nc7 18.Rfd1 Nd7 19.Qe2 and Black remains cramped; B) 8...h5 stops the standard kingside hack, but we switch to positional play with 9.Be2! Nbd7 10.0-0 when ...h7-h5 looks entirely out of place. For example: 10...0-0 (trying to delay castling is likely to run into a strong Nd5, as after 10...Qc7 11.a4 Ne5 12.Nd5 Nxd5 13.exd5 0-0 14.Rad1 it’s hard to suggest an active plan for Black, while h2-h3/f2-f4-f5 is bound to be unpleasant) 11.a4 Ne5 12.a5 Bd7 13.Nd5 Nxd5 14.exd5 Rc8 15.Bh6 e6 16.Bxg7 Kxg7 17.f4 Nc4 (GlazmanSiikaluoma, email 2009) 18.Bxc4 Rxc4 19.dxe6 fxe6 20.Rae1 and Black’s structure is a litany of weaknesses; C) 8...Nbd7 9.g4! (this gains in strength when ...Nbd7 is played, as ...Nfd7 is no longer a possible answer to g4-g5) and now: C1) 9...h6 10.0-0-0 b5 11.h4 Ne5 12.Rg1 is much better for White, since the h6-pawn stops Black castling; C2) 9...Ne5 is too extravagant after direct play by White: 10.0-0-0 b5 11.g5 Nh5 (11...Nfd7? 12.f4 Ng4 13.Bg1 maroons the g4-knight) 12.f4 Nc4 13.Bxc4 bxc4 14.Qe2 0-0 15.Qxc4± picks up the c4-pawn for minimal compensation; C3) 9...b5 C31) 10.0-0-0! Bb7 11.h4 White’s play is clear-cut, but as Black scores quite well in the Dragadorf, I’ve offered some pointers: C311) 11...Nb6 12.Bh6 Bxh6 13.Qxh6 b4 14.Nce2 e5 15.Nb3 made it difficult for Black to complete his development in Freytag-Genga, email 2013; C312) 11...Rc8 12.h5 Ne5 13.Be2 Rg8 was played in two email games, but it’s obvious that something is wrong with Black’s position if he can’t ever castle, and simply 14.Kb1 Qc7 15.h6! Bh8 16.Rhe1 followed by g4-g5 and f2-f4 looks strategically winning for White; C313) 11...h5 12.g5 Nh7 13.f4± At some point the f4-f5 break will finish Black, see Winkler-De Blasio, email 2010. C32) 10.a4 b4 11.Na2 a5 12.c3 is less consistent but not bad either, as the ambitious 12...Bb7 13.cxb4 0-0 14.g5 Nh5 15.Bb5 doesn’t give Black enough for the pawn. However, White has to play precisely to keep control. En route to the modern main line 7.f3 Nc6 7...0-0 8.Qd2 leaves Black nothing better than 8...Nc6 anyway, as the 8...d5?! 9.e5 Ne8 10.f4 f6 11.Nf3 of SutelaFischer, email 2012, demonstrates. 8.Qd2 8...0-0 8...Bd7 9.g4! is very unpleasant when Black can’t retreat with ...Nd7: A) 9...h5 10.g5 Nh7 11.0-0-0 Rc8 can be met in various ways, but the key lies in f4-f5: 12.f4 0-0 13.Be2 Re8 14.f5! Qa5 15.Kb1 Black is terribly passive in this position, and can’t break out easily as grabbing the f5-pawn in any version loses to g6 breakthroughs, and otherwise 15...gxf5 16.Nxf5 Bxf5 17.exf5 Nb4 18.Bd4 Rxc3 19.Qxc3 Qxa2+ 20.Kc1 Nxg5 21.Bxg7 Qa1+ 22.Kd2 Ne4+ 23.Ke3 Nxc3 24.Rxa1 Nxc2+ 25.Kd3 Nxe2 26.Kxc2 Kxg7 27.Ra4! is winning for White, due to the trapped e2-knight; B) 9...0-0 10.0-0-0 transposes to 8...0-0 9.0-0-0 Bd7; C) 9...Rc8 10.0-0-0 Ne5 11.h4 It is hard for Black to count on a successful attack without the inclusion of both rooks. 11...h5 (11...Qa5 was once played by Nakamura, but none of Black’s tricks land after the precise 12.Be2!N 12...b5 13.a3 b4 14.Na2!+–) 12.g5 Nh7 13.f4 Ng4 14.Bg1 0-0 15.f5 Black’s position is already close to lost, as demonstrated in several games, including Pruijssers-Pert, PRO Chess League 2017. 9.0-0-0! I used to play De la Villa’s recommended 9.Bc4, but 9.0-0-0 is both easier to learn and the stronger continuation. This was incidentally a major factor in my recommending the Maroczy Bind over 5.Nc3 against the Accelerated Dragon. 9...d5! is the only logical move, as White will use the two tempi that could have been spent on Bc4-b3 to win any attacking race. But first we will cover some thematic developing alternatives. A) Black only loses time with 9...Qa5?! 10.Kb1 Bd7 11.Nb3 Qc7 12.g4±; B) 9...Be6? is the main line against 9.g4, but ineffective here: 10.Nxe6 fxe6 11.Kb1 Rc8 12.Ne2!? (intending Nf4) 12...Qc7 (12...Ne5 13.Nd4 Qd7 14.Bb5 Nc6 15.Ba4!+– as in To-Parkanyi, Budapest 2010, is no better) 13.Nf4 Nd8 14.h4! Bh6 15.c3 and White is already technically winning – Black has no constructive ideas; C) 9...Bd7 10.g4 Rc8 11.h4! is an extremely fast attack by White: C1) 11...Ne5 doesn’t work well as a later ...Nc4 would effectively concede a loss of two tempi compared to the Yugoslav Attack: 12.h5 Qa5 13.a3! (killing any ...Rxc3 or ...Nxf3 tricks) 13...a6 (13...Nxf3 14.Nxf3 Bxg4 15.Bg2 Bxh5 16.Nd5 Qxd2+ 17.Rxd2 Nxd5 18.exd5 is a woeful endgame for Black, as advancing his kingside pawns will inevitably weaken vital squares; 13...Rxc3 14.Qxc3 Qxc3 15.bxc3 Rc8 16.Bd2!± isn’t one of the better versions of the typical Dragon endgame for Black) 14.Be2 b5 15.Kb1± and Black’s attack made no headway in Locio-Ganin, email 2007; C2) 11...h5 12.gxh5 Nxh5 13.Rg1 This position has occurred frequently in practice, but Black’s awful score speaks for itself; f4-f5 is going to rip Black’s king apart: 13...a6 (13...Ne5 14.Bh6 Qa5 15.Bxg7 Kxg7 16.Bb5! is very strong, gunning for Nf5, and if 16...Be6 17.f4 Nxf4 18.Qxf4 Rxc3 19.bxc3 Qxc3 20.Qf2! keeps control for the win) 14.Kb1 b5 15.a3!± There isn’t a lot Black can do against the plan of Be2 and eventually f2-f4, and despite his best efforts he went down in Zlotkowski-Bresadola, email 2008; D) 9...Nxd4 10.Bxd4 and now: D1) 10...Qa5 11.Kb1 Rd8 is a very artificial way to escape the Nd5 threat, and after 12.Bc4!? Bd7 13.h4 Rac8 14.Bb3 White has a turbo-charged version of the Yugoslav Attack. Note that 14...h5 can already be met by the standard breakthrough 15.g4! hxg4 16.h5 gxh5 17.Qc1!+– followed by Nd5, with a decisive attack; D2) 10...Be6 11.Kb1! (preventing 11...Qa5 because of 12.Nd5! and the intermediate check) 11...Qc7 (other moves can be met in the thematic way. One exception is 11...Rc8 12.h4 h5, against which I’d anticipate ...Qa5 with 13.a3! Nd7 14.Nb5! a6 15.Bxg7 Kxg7 16.Nd4±, when g2-g4 will give White a strong attack) 12.h4! (in many cases we can play h4-h5 without the preparatory g2-g4) 12...Rfc8 (12...h5? 13.Nd5 Bxd5 14.exd5 was already losing for Black in SzaboLovakovic, email 2011, as Black is unable to prevent the opening of the kingside with g2-g4) 13.h5 Qa5 (this move is possible when Nd5 Qxd2 Nxe7 can be met by ...Kf8. 13...Nxh5? is easily refuted: 14.Bxg7 Kxg7 15.g4 Nf6 16.Qh6+ Kg8 17.e5! dxe5 18.g5 Nh5 19.Rxh5 gxh5 20.Bd3 e4 21.Nxe4+–) 14.hxg6 D21) 14...fxg6 is safer than 14...hxg6, but splits Black’s structure: 15.a3 15...Rab8 (15...b5 16.Nxb5 Qxd2 17.Rxd2± is a free pawn; after 15...Bf7 16.g4 Rab8 17.g5 Nh5 18.Bxg7 Kxg7 19.Bh3 Rc4 20.Bg4 b5 Black has held twice in practice, but 21.Rh2!± prevents all Black’s counterplay, as ...b5-b4 is answered with Nd5 and otherwise it’s not clear what Black does while White improves his position) 16.Qe3! (a powerful move, setting up e4-e5 and Nd5, not to mention g4-g5) 16...Rc6 (16...a6 17.g4 b5 18.Nd5! gives White a decisive initiative, e.g. 18...Qd8 19.g5 Nh5 20.Bxg7 Kxg7 21.f4+– and Bh3/f4-f5 is coming) 17.Nb5!? Ra8 18.Bc3N 18...Qb6 19.Qxb6 axb6 20.Nd4 Rxc3 21.Nxe6 Rcc8 22.g3 White has a gigantic positional advantage with the octopus on e6; D22) 14...hxg6 15.a3 From this point Black has tried virtually every way to postpone defeat. D221) In Pecka-Mezera, email 2011, White’s attack played itself: 15...a6 16.Bd3 Rc6 (16...b5 17.Qg5! Rab8 transposes to 15...Rab8) 17.Rh2 Rac8 18.Rdh1 Bc4 19.Bxc4 Rxc4 20.g4+–; D222) 15...Bc4?! doesn’t make sense to me before Bd3 has been played, and 16.Bxc4 Rxc4 17.Qc1 e6 (else Bxf6/Nd5) 18.Rd3!N 18...Rac8 19.Qd2± and g4-g5 leaves Black waiting for the end, as his king and d6-pawn are both vulnerable; D223) 15...Rab8 16.Bd3 b5 (16...Bc4 17.Bxc4 Rxc4 18.Qf2! (this correspondence move has proven a refutation) 18...Rbc8 19.Rd3+– See the stem game Quattrocchi-Joppich, email 2010) 17.Qg5 Black has tried nearly everything here, but his position is already objectively lost: D2231) 17...Rc5 18.Bxc5 dxc5 19.Qxc5+– transposes to Hungaski-Kiewra, Los Angeles 2011, in case you’re unsure of your ability in converting a large material advantage; D2232) The desperate 17...Rxc3 18.Bxc3 Qa4 is refuted by 19.Rh4 b4 20.e5!N 20...Nd5 21.Bd2 Qa5 22.Rdh1 when Black can resign; D2233) 17...Nh7? 18.Rxh7! hardly requires calculation, Ruiz Castillo-Perez Lujan, Guatape 2016; D2234) If 17...a6 18.f4 is winning, for example: 18...Rb7 19.Rh4! Rbc7 20.f5N 20...b4 21.axb4 Qxb4 22.fxe6 Qxd4 23.exf7+ Kxf7 24.e5+–; D2235) After the natural 17...Bc4 18.Bxc4 Rxc4 19.Nd5 White’s attack strikes first: 19...Rxd4 (19...Qd8 20.Bxf6! exf6 21.Qh4+– was Stojanovic-Galic, Bihac 2010. Black lacks a good defence to the Rh2, Rdh1 and Qh8! mating motif) 20.Nxe7+! Kf8 21.Rxd4 and Black was toast in Baratosi-Galic, Belgrade 2007, as 21...Kxe7 22.e5 wins everything; D2236) 17...d5!? is the best chance to confuse White, as he has too many winning lines to choose from! I’ll show the most clinical one: 18.Nxd5 Bxd5 19.exd5 b4 20.Bxg6 fxg6 (20...bxa3 21.Rh7! forces resignation, as Black can’t cover against Bxf7) 21.Qxg6 Qa4 22.Bxf6 exf6 23.Rh7 Qxc2+ (otherwise Rdh1/Rh8 is mate) 24.Qxc2 Rxc2 25.Rxg7+ Kxg7 26.Kxc2 and the rook ending is a trivial win; D2237) 17...Qc7 18.e5 dxe5 19.Bxe5 19...Qc5 (19...Qb6 20.Bxg6! fxg6 21.Qxg6 is killing, based on two tricks: 21...Bf7 22.Rh8! and 21...Ne8 22.Rd6! exd6 23.Qxe6+ Kf8 24.Bxg7+ Kxg7 25.Qg4+ Kf8 26.Rh8+ with mate in four) 20.f4+– You can enjoy the bludgeoning that was Lim-Zhang, Kuala Lumpur 2008, in the games section. The modern main line 9...d5! 10.Qe1! This retreat places considerable pressure on Black’s centre and avoids certain options available after the more common 10.exd5 Nxd5 11.Nxc6 bxc6 12.Bd4, particularly 12...Bxd4 13.Qxd4 Qb6, which Gawain Jones in GM Repertoire: The Dragon demonstrates is quite solid for Black. Those looking for a simple answer might consider the rare 14.Qe5!? Nxc3 15.Qxc3 Be6 16.h4 Rfd8 17.Re1!N 17...Qd4 18.Qxd4 Rxd4 19.Re5! with White’s fewer pawn islands defining his endgame edge, though I think my recommendation is stronger. 10...e5 Black should move his e-pawn, as most other moves fail tactically and 10...Re8 11.Bb5!± is unpleasant. 10...e6 was Dragon expert Jones’s most recent preference: 11.h4! and now: A) 11...Qa5 12.h5! dxe4 13.h6N 13...Bh8 14.Nxc6 bxc6 15.Nd5! Qd8 16.Nb6 Qxd1+ 17.Qxd1 axb6 18.a3± is an impressive tactical display!; B) 11...h5? only fuels White’s attack: 12.g4! hxg4 13.h5 and the h5-knight is burdened: 13...Nxd4 14.Bxd4 Nxh5 (Black can’t ignore the pawn as h6-h7 was threatened; or 14...gxh5 15.e5) 15.fxg4 Bxd4 16.Rxd4 Qg5+ 17.Kb1 e5 (17...Qxg4 18.Rd3! Qg5 19.Be2 Nf4 20.Rf3 gives a decisive attack with best play) 18.Rd3N 18...Nf6 19.Nxd5 White has the open h-file for a triumphant attack; C) 11...Re8 12.Bb5!N is a familiar theme; D) 11...Qe7 12.h5! As usual in the Dragon, we welcome the opening of the h-file. 12...dxe4 (12...Nxh5 13.g4 Nxd4 14.Bxd4 Bxd4 15.Rxd4 Qg5+ 16.Kb1 already forces Black to cut his losses with 16...e5, as 16...Nf4 17.exd5 Nxd5 18.Ne4 Qe5 19.Qd2! gives a crushing attack for the pawn with Bc4 and g4-g5) 13.hxg6 fxg6 14.Nxc6 bxc6 15.Qh4! exf3 16.Ne4 Qb7 17.Bd4 (not the only strong move) 17...fxg2 18.Bxg2 Nh5 19.Rhf1 and Black will be hard pressed to survive the onslaught of White’s entire army; E) 11...Qc7 12.Ndb5!ƒ This intermezzo refutes Black’s concept, as we’ll see in Van de Ploeg-Gleyzer, email 2013. 11.Nxc6 bxc6 12.exd5 Black recaptures with the pawn 12...cxd5 13.Bg5 Be6 14.Bc4 Now we understand the importance of 10.Qe1, to clear the way for the d-file pin. 14...Qc7 14...Qb6 15.Bxf6 Bxf6 16.Nxd5 Bxd5 17.Rxd5 (Black has some activity, but not enough for a full pawn) 17...e4! (Black should activate his bishop, as after 17...Rad8 18.c3N 18...Rxd5 19.Bxd5± White’s bishop is even more active) 18.Rb5 Qc7 19.Qxe4 Rae8 20.Qd3 Qf4+ 21.Kb1 Re3 22.Qf1! (the absence of weaknesses in White’s camp allows him to resist Black’s aggression) 22...Rfe8 23.Bd3!N 23...Qxh2 24.Be4 Qg3 25.Rb3!? Rxb3 26.axb3 and White’s winning chances with the extra pawn are pretty reasonable. 15.Bxd5! Accepting the sacrifice is demanding, but also more rewarding. 15.Bxf6 dxc4 16.Bxg7 Kxg7 17.h4! is also better for White, as we’ll see in Hess-Spirin, email 2009, but accepting the sacrifice is stronger and scores heavily. 15...Nxd5 16.Nxd5 Bxd5 17.Rxd5 Now Black must decide how to place his major pieces. 17...Qc4 A) 17...Rac8 18.Qd2 Rfe8 19.Qd3² covers the position perfectly; B) 17...a5 18.Qd2 Rab8 19.b3 a4 20.Kb1 Rbc8 saw Black save a draw in Krivic-Moreira, email 2009, but an improvement is 21.Rd7! Qb6 22.Be7! Rfe8 23.Qd5 and Black is tied up. The attempt to break out with 23...e4 24.Bd8 Qe6 25.Qxe6 Rxe6 26.fxe4 Rxe4 27.Rhd1 results in a (passed) pawn up endgame with excellent winning chances; C) On 17...Rab8 18.Qa5!± was very strong in Sethuraman-Kanter, Sharjah 2017. 18.Ra5 The rook defends the queenside well from a5, and Qe4 will follow against most tries. 18...Qc7 18...Rab8 19.Qe4 Qc7 20.Ra4 Rfc8 21.b3± also didn’t give Black enough counterplay to save the game in StronskySpirin, email 2009. 19.Ra4 Rfc8 19...h6 20.Bd2 Rac8 21.Qe4 f5 22.Qd3 Kh7 23.c3 Rfd8 24.Qc2² is probably the best try, but White has consolidated his extra pawn. 20.Qe4 f5 21.Qd5+ Kh8 22.c3± Black was just a pawn down in Siigur-Hagström, email 2011. The main move 12...Nxd5 13.Bc4 Be6 14.Kb1! This productive waiting move forces Black to pick his set-up. 14...Rb8 Put simply, rooks belong opposite the opponent’s queen or king! A) 14...a5 prepares ...Rb8 but is a bit slow after 15.h4!² as we’ll see in Nickel-Rook, email 2012; B) 14...Nxc3+ 15.Qxc3 Qe7 tries to simplify Black’s way out of the problems (15...Bd5 is well met by 16.h4!²): 16.Bb3 Bxb3 17.cxb3!N however safeguards White’s king, allowing him to focus fire on Black’s isolated queenside pawns after 17...Rfc8 (17...e4 18.Qxc6 exf3 19.Qxf3± is a safe pawn grab; 17...Qe6 18.Qc2 a5 might be best, but 19.Rd2ƒ retains a stable positional preponderance) 18.Qc2 Qe6 19.Bc5!±; C) 14...Re8 15.Ne4 also favours White with Bc5/g2-g4-g5 (or h2-h4-h5) plans, as in the model game Leko-Trent, Douglas 2016. 15.Ne4 f5 Black’s options are limited due to the threat of Bxa7. 15...Qc7 16.Bc5 Rfd8 17.g4 gives White full control of the position, as the opening of the kingside with ...f7-f5 is obviously in White’s favour: 17...h6 18.Rg1!N (this is an important prophylaxis against ...f7-f5. 18.Bb3 a5 19.h4 f5 20.gxf5 gxf5 21.Nc3 Nxc3+ 22.Qxc3 is structurally good for White, but most Dragon exponents will be happy with their active counterplay after 22...Bxb3 23.axb3 Kh7) 18...a5 19.a4! (a typical means of fixing the queenside. 19.Bb3 Ra8 20.a4 is similar) 19...Rb7 20.g5! h5 21.Qf2² and with the kingside fixed, White can focus on Black’s queenside weaknesses, which will only become more exposed with the exchange of pieces. 16.Bxa7! This is not as brave as it looks, since our knight is not truly threatened. 16...Ra8 A) 16...Qe7 17.Bc5! Qb7 18.Bb3 fxe4 19.Bxf8 Rxf8 20.fxe4 Nf4 21.Qc3!± was a key improvement over Jones’s analysis, played in Ganguly-Quintilliano Pinto, Doha 2016; B) If 16...Qc7? 17.Bxb8 Rxb8 18.Ng5! e4 19.Bb3 Qe5 20.c3+– refutes Black’s sacrifice. 17.Bc5 Rf7 18.Bb3 fxe4 19.fxe4 Rd7 20.exd5 (Ganguly-Cuenca Jimenez, Spanish tt 2016) 20...cxd5 This is a better practical try, but Black is still a pawn down after 21.Bb4! Qb6 22.a3± when the white pawns and bishops do a great job of protecting the king. Summary 4...Nf6 5.Nc3 g6: 6.Be3 a6/6...Bg7 7.f3 a6 – +0.60 6...Bg7 7.f3 Nc6 8.Qd2: 8...Bd7 – +0.80 8...0-0 9.0-0-0: 9...Nxd4 – +0.80 9...d5 10.Qe1: 10...e6 – +0.85 10...e5 – +0.35 12.1 Anish Giri 2776 Ivan Ivanisevic 2643 Doha 2014 (3) 1.Nf3 c5 2.e4 d6 3.d4 Nf6 4.Nc3 cxd4 5.Nxd4 g6 6.Be3 a6 7.f3 b5 8.Qd2 Bb7 9.g4!? 9.a4 9...h6 A) 9...Bg7 10.0-0-0 Nbd7 transposes to 6...Bg7 7.f3 a6; B) 9...h5!? 10.g5 Nfd7 avoids the h-file attack, but 11.f4 Bg7 12.0-0-0 0-0 13.Bg2² and f4-f5 will also be problematic. 10.0-0-0 Nbd7 11.a3! 11.h4 b4! 12.Nce2 e5 13.Nb3 a5= is the type of counterplay we would rather avoid. 11...Rc8 12.h4 Qa5?! 12...Ne5 13.Rh3!?N is a wrinkle, delaying Be2 so that ...Nc4 loses its sting: 13...Nfd7 14.Be2 h5 15.gxh5 Rxh5 16.Bg5 Nc4 17.Qe1 when f3-f4 and h4-h5 will wrench open the kingside. 13.Nb3 13.Kb1 Ne5 14.Be2± 13...Qc7 14.Qf2! 14.Be2 14...e6 This deprives Black’s structure of its flexibility, but 14...Bg7 15.Bd4 Ne5 16.Kb1 Nfd7 17.g5!? hxg5 18.Be2ƒ would give White a very strong initiative. 15.Kb1 Qb8 16.Bh3! Rxc3 A desperate sacrifice, but I doubt there’s anything better. 17.bxc3 Qc7 17...Ne5 18.Bd4 18.g5!+– Nh5 19.Bg4 hxg5 20.hxg5 Be7 21.Bd4 Rg8 22.Bxh5 gxh5 23.Rxh5 e5 24.Be3 Qxc3 25.Bd2 Qc7 26.Ba5 Qb8 27.Bb4 Bc8 28.Rh6 Qb6 29.Qh2 Rg6 30.Rxg6 fxg6 31.Qd2 Nc5 32.Nxc5 dxc5 33.Ba5 Qe6 34.Bd8 Bf8 35.Bf6 Bd7 36.Qa5 1-0 12.2 Gyula Sax 2492 Kevin Goh Wei Ming 2449 Kecskemet 2011 (3) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 a6 7.f3 b5 8.Qd2 Bb7 9.a4 b4 10.Na2 e5 11.Nb3 d5 12.Bg5 Nbd7 13.exd5 Bxd5 14.Qxd5 Nxd5 15.Bxd8 Kxd8 16.0-0-0± Ne3 16...Bh6+ 17.Kb1 Ne3 18.Rd3 a5 19.c3± Hall-Thurlow, email 2011. 17.Rd3 Nf5 18.Be2 Ra7?! Black seeks to avoid material loss, but this is very slow. 18...Kc7 19.Rhd1 Nc5 20.Nxc5 Bxc5 21.Rd7+ Kb6 22.Rxf7± 19.Rhd1 Kc8 20.g4 20.Kb1 20...Ng7 21.Rd5?! 21.c3! opens the floodgates to Black’s king. 21...Ne6 22.Bxa6+ 22.Ra5 was better. 22...Rxa6 23.Rxd7 Rxa4 24.Kb1 Ng5? Now all White’s pieces enter the attack, whereas 24...h5!± continues fighting. 25.h4 25.R1d5! 25...Nxf3 25...Ne6 26.Rxf7 Nd8± 26.Rd8+ Kc7 27.R1d7+ Kc6 28.Rxf7+–... 1-0 (36) 12.3 Raimo Sutela 2320 Detlev Fischer 2321 ICCF email 2012 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 0-0 8.Qd2 d5? 9.e5 Ne8 10.f4 f6 10...Nc6 11.0-0-0 Nc7 12.Be2 Nxd4 13.Qxd4 e6 14.h4!± 11.Nf3± e6 11...fxe5 12.Qxd5+ Qxd5 13.Nxd5 exf4 14.Bc5! Nc6 15.Nxe7+ Nxe7 16.Bc4+ Kh8 17.Bxe7 Bxb2 18.Rd1 Bc3+ 19.Ke2 Kg7 20.Bxf8+ Kxf8 21.Rhf1± Mancuso-McLeod, email 2010. 12.0-0-0 Nc6 Black’s position would be quite playable if White were forced to trade on f6, but he can hack Black’s king to bits instead! 13.h4! fxe5 14.fxe5 Nxe5 15.Nxe5 15.h5!? 15...Bxe5 16.h5 Qc7 The radical 16...g5 is the only way to avoid the complete opening of the kingside: 17.Bxg5 Qd6 18.Bb5 Bd7 19.Bxd7 Qxd7 20.Rhe1 Rf5 21.g4 Bxc3 22.bxc3 Rf7 23.Qe2± 17.Nb5 Qf7 18.hxg6 hxg6 19.Bd3 Black’s king is too open for a successful defence. 19...Bd7 20.Nd4 Nd6 21.Nf3 Bg7 22.Ng5 Qf6 23.c3 Nf5 24.Nh7 And 1-0 (53). 12.4 Thorsten Winkler 2522 Massimo De Blasio 2536 ICCF email 2010 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 a6 8.Qd2 Nbd7 9.g4 b5 10.0-0-0 Bb7 11.h4 h5 12.g5 Nh7 13.f4± Nc5 A) 13...0-0 14.f5 Nc5 15.Bg2 Rc8 16.Rhf1 Qe8 17.Nd5+– Efendiyev-De Blasio, email 2010; B) 13...Qa5 intends ...b5-b4, but that can be ignored: 14.Bg2! b4 (14...Rc8 15.Kb1 Rxc3 16.bxc3 0-0 is unsound for many reasons, but the most compelling is 17.e5! Bxg2 18.Qxg2 Qxc3 19.Rd3 Qc4 20.Nc6!N 20...Re8 21.Bd2+–) 15.Nd5 Bxd5 16.exd5 Qxa2 17.Qxb4 Rb8 18.Qa3 Qxa3 19.bxa3+–; Nc6 next would be fatal, but 19...Bxd4 is not much better. 14.f5 Rc8 14...b4 is refuted in champagne style: 15.fxg6! bxc3 16.gxf7+ Kxf7 17.Qf2+ Bf6 18.Bc4+ Ke8 19.gxf6 Nxf6 20.e5! cxb2+ 21.Kxb2 Bxh1 22.exf6+– Overton-Sutton, email 2010. 15.fxg6 Or 15.Bh3. 15...fxg6 16.Bh3 b4 17.Nd5 Black has no alternatives for the next moves, ultimately finishing an exchange down. 17...Nxe4 18.Qxb4 Bxd5 19.Qa4+ Kf7 20.Rhf1+ Nhf6 20...Kg8? 21.Be6+ Bxe6 22.Nxe6+– 21.gxf6 Bxf6 22.Bxc8 Qxc8 23.Bg5 Qb7 24.Bxf6 Nxf6 25.Ne2 Now it’s largely a matter of technique, as Black’s king is unsafe. White won on the 68th move. 12.5 Roeland Pruijssers 2502 Richard Pert 2414 PRO League INT rapid 2017 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 Nc6 8.Qd2 Bd7 9.g4 Rc8 10.h4 h5 11.g5 Nh7 12.0-0-0 Ne5 13.f4 Ng4 14.Bg1 0-0 15.f5± Re8 A) 15...Ne5 16.Kb1 b5 17.Ncxb5 Rb8 18.Rh3! a6 19.Nc3+– De Cresce-Alexander, email 2002; B) 15...Qa5 16.Rh3! (the ideal square for the rook, preventing ...Rxc3 counterplay) 16...Ne5 17.Qg2 Rfe8 18.Nd5 e6 19.Ra3 Qd8 20.Nf4 and the pressure was too much in Chopin-Gmür, email 2005. 16.Be2 Ne5 17.Be3 17.Kb1 17...Nc4 18.Bxc4 Rxc4 19.fxg6 White goes in for messy tactics, when he could sit on his dominant position with 19.Qd3 Qc8 20.Rhf1+–. 19...fxg6 20.Nf5 Rxc3 21.Nxg7 Rxe3 22.Nxe8 Rxe4 23.Nxd6 exd6 24.Qxd6 Nf8 25.Qd5+ Re6 26.Qxb7 Qe8 27.Rhf1² Re7 28.Qd5+ Be6 29.Qa5 29.Qd8 was better. 29...Bf5! 30.Rfe1 Rxe1?! The correct method of play is to keep your rook when your opponent has one more, as the second rook can easily become superfluous. 30...Qc6= and ...Rc7 was therefore correct. 31.Rxe1 Qc6 32.Qd2 32.Qc3! Qxc3 33.bxc3² is ugly, but avoids the fork in the next note. 32...Ne6? 32...Qc4!= 33.b3!± Now White has consolidated his position. He eventually converted on move 58. 12.6 Liliana Susana Locio 2257 Alberto Walter Ganin 2151 ICCF email 2007 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 0-0 8.Qd2 Nc6 9.0-0-0 Bd7 10.g4 Rc8 11.h4 Ne5 12.h5 Qa5 13.a3 a6 14.Be2 b5 15.Kb1± Rfe8 15...Rxc3 16.Qxc3 Qxc3 17.bxc3 Rc8 18.Kb2± 16.hxg6 fxg6 17.Nb3 Qd8 18.g5 By this point, everything is good: 18.Bd4 Nc4 19.Bxc4+ bxc4 20.Nc1±; or 18.Nd5!?. 18...Nh5 19.Nd5 Rf8 20.Nb6 Ng3 Black looks for complications as 20...Rb8 21.f4 Rxb6 22.Bxb6 Qxb6 23.fxe5 Bxe5 24.Bxh5 gxh5 25.Rdf1! gives White a strong attack. 21.f4 Nc4 22.Nxc4 bxc4 23.Bxc4+ Rxc4 24.Qd5+ Rf7 25.Qxc4 Nxh1 26.Rxh1± Qa8 Black has better chances to defend with the queens off: 26...Qc8 27.Nd2 Qb7 28.Qb4 Qb5 29.c4 Qc6 30.Qb8+ Be8 31.Rc1 e5 32.fxe5 Bxe5 33.b3 Rf8 34.c5 a5 35.Qb6 d5 36.Qxc6 Bxc6 37.exd5 Bxd5 38.Kc2 a4 39.bxa4 Ra8 40.Kd3 Rxa4 41.Nc4 Bg3 42.Bd2 Ra8 43.Kd4 Rd8 44.Be3 Bc6+ 45.Kc3 Re8 46.Rb1 Bc7 47.Bd4 Re4 48.Rf1 Rg4 49.Rf6 Bg2 50.Ne3 Rxg5 51.Nxg2 Rxg2 52.Ra6 Bf4 53.Ra7 h5 54.c6 Ra2 55.a4 h4 56.Kb3 1-0 12.7 Arkadiusz Zlotkowski 2382 Guido Bresadola 2388 ICCF email 2008 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 0-0 8.Qd2 Nc6 9.0-0-0 Bd7 10.g4 Rc8 11.h4 h5 12.gxh5 Nxh5 13.Rg1 a6 14.Kb1 b5 15.a3± e6 A) 15...b4 16.axb4 Nxb4 17.Be2 a5 is too slow after 18.f4 Nf6 19.f5+–; B) 15...Nxd4 16.Bxd4 Bxd4 17.Qxd4 Be6 18.Rg5 will also force open the kingside with a timely Rxh5. 16.Be2! Be8 16...Qxh4 17.Rh1 Qf6 18.Nxc6 Bxc6 19.Rdg1± – Rxh5 is threatened, among others. 17.Nb3 Na5 18.Nxa5 Bxc3 19.bxc3 Qxa5 20.Qxd6 Qxc3 21.Bd3 Rc6 22.Qe7 Rc7 23.Bd2! This intermezzo ends Black’s resistance. 23...Qe5 23...Qxc2+ 24.Bxc2 Rxe7 25.Bb4 24.Qb4+– Qg7 25.f4 f5 26.Rde1 Kh7 27.Rg5 Qf6 28.Reg1 Rh8 29.Be2 Ng7 30.h5 Kg8 31.Rxg6 Bxg6 32.Rxg6 Qf7 33.Bc3 Rh7 34.Be5 1-0 12.8 Gaetano Quattrocchi 2346 Ulrich Joppich 2453 ICCF email 2010 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 0-0 8.Qd2 Nc6 9.0-0-0 Nxd4 10.Bxd4 Be6 11.Kb1 Qc7 12.h4 Rfc8 13.h5 Qa5 14.hxg6 hxg6 15.a3 Rab8 16.Bd3 Bc4 17.Bxc4 Rxc4 18.Qf2 Rbc8 19.Rd3 The attack plays itself as Black can’t do much to distract. 19...Kf8 19...b5 fails to 20.Bxf6! Bxf6 21.Nd5 Kf8 22.Nxf6 exf6 23.Rxd6 Qc7 24.Rd2+–. 20.g4 b5 If 20...R4c6 21.Qd2 sets up f3-f4 and the opening of the kingside. 21.Nd5 Rxc2 22.Qh4 R2c4 23.g5 Nh5 24.Bxg7+ Kxg7 25.Nxe7 Rh8 26.Qh2 Qd8 27.Nf5+! This breakthrough caps off the attack. 27...gxf5 28.Rxd6 Qe7 29.Rh6 Rxh6 30.gxh6+ Kh7 31.Qxh5 fxe4 32.Rg1 As usual, king safety and piece activity are decisive factors in queen and rook positions. 32...exf3 33.Rg7+ Kh8 34.Qxf3 Qe4+ 35.Qxe4 Rxe4 36.Rxf7... 1-0 (43) 12.9 Lim Yee Weng 2367 Zhang Ziyang 2441 Kuala Lumpur 2008 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 Nc6 8.Qd2 0-0 9.0-0-0 Nxd4 10.Bxd4 Be6 11.Kb1 Qc7 12.h4 Rfc8 13.h5 Qa5 14.hxg6 hxg6 15.a3 Rab8 16.Bd3 b5 17.Qg5 Qc7 18.e5 dxe5 19.Bxe5 Qc5 20.f4+– 20...Rb7 A) 20...Ng4 21.Bxb8 Qxg5 22.fxg5 Rxb8 (you know things are bad when the best move is to give up a cold exchange!) 23.Ne4 Ne3 24.Rd2 Bf5 25.Re2 Nc4 26.c3+– Betker-Nöth, email 2009; B) 20...b4 21.Bxb8 Qxg5 22.fxg5 Rxb8 23.gxf6 bxc3 24.fxe7! (the key move, so that Black isn’t in time to play ...Rxb2 and Ba2) 24...Bf6 25.b3 Bxe7 26.Rde1 Bxa3 27.Bxg6+–; C) 20...Rb6 21.Bxg6! fxg6 22.Qxg6+– resembles the game. 21.Bxg6 fxg6 22.Qxg6 Bf5 22...Bf7 23.Rh8+! Kxh8 24.Qxf7+– 23.Qxf5 b4 24.axb4 Rxb4 25.Nd5 25.Qg6!, threatening 26.Rh7, is more clinical. 25...Rb7 26.Rh3 Nxd5 27.Qe6+ Kf8 28.Bxg7+ Kxg7 29.Rg3+ 1-0 12.10 Geert van de Ploeg 2301 Leonid Gleyzer 2282 ICCF email 2013 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 0-0 8.Qd2 Nc6 9.0-0-0 d5 10.Qe1 e6 11.h4 Qc7 12.Ndb5± Qa5 The queen finds herself targeted on other squares: A) 12...Qe7? 13.Bf4! d4 14.Bd6+– Wang-Pham, Ho Chi Minh City 2017; B) 12...Qb8 13.exd5 Nxd5 (13...exd5 14.h5! a6 15.h6 Bh8 16.Nd4 Re8 17.Qd2± Gesicki-Nemec, email 2012) 14.Nxd5 exd5 (the IQP allows White to play more positionally) 15.Qd2 a6 16.Bf4 Be5 (16...Ne5 17.Nd4 Bd7 18.h5±) 17.Bxe5 Qxe5 18.Re1 Qg3 19.Nc3 Bf5 20.Nxd5 Rfd8 21.Bc4 and White had an extra pawn and the attack in Topalov-Lu, Baku 2015. 13.h5! 13.exd5 exd5 14.Qf2 Be6 15.a3 is a safe positional edge, but we can refute Black’s variation. 13...dxe4 14.fxe4 14.hxg6!? fxg6 15.Be2 a6 16.Nd6 Nd5 17.Nxd5 Qxe1 18.Rhxe1 exd5 19.fxe4 d4 20.Bc4+ Kh8 21.Bg5 and Black is sorely underdeveloped. 14...Rd8 14...Ng4 15.Bd2 a6 16.Nd6 Qc5 17.Qh4 Qxh5 18.Qxh5 gxh5 19.Rxh5± 15.hxg6 15.Be2!?± 15...Rxd1+ 16.Qxd1 hxg6 17.Nd6 Ne5 18.Be2± White has a great attacking position, but he should proceed accurately. 18...Bd7 18...b5!? 19.Bd4! b4 20.Ncb5± Qxa2 21.Bxe5 Qa1+ 22.Kd2 Nxe4+ 23.Nxe4 Qxd1+ 24.Rxd1 Bxe5 25.Nc5+– 19.Qd2 Neg4 20.Bd4?! I don’t think White’s eventual victory was because of this move. A) 20.Nxf7!? Bc6 21.Ng5 Rd8 22.Bxg4 Nxg4 23.Qe1 Bxc3 24.bxc3 Rd7 25.Nxe6 Qxa2 26.Bd4 Rh7 27.Rxh7 Qa1+ 28.Kd2 Qxe1+ 29.Kxe1 Kxh7 30.Bxa7 is favoured by the engine, but this endgame looks drawish to me; B) 20.e5! Qxe5 21.Bf4 Qa5 22.Nxf7 Kxf7 23.Bxg4 Rd8 24.Bf3 seems the correct execution, keeping the pieces on for long-term pressure against Black’s king. 20...e5 21.Bg1 Qc7 22.Bc4 Rf8 22...Be6 23.Bxe6 fxe6 24.Ndb5 Qc6² 23.Bb3 a6 24.Nc4 Be6 25.Nb6 Rd8 26.Qe2 Bxb3?! This is a strategic mistake as it allows White full control over d5. 26...Bh6+ 27.Kb1 Rd2 28.Qf3 Kg7 29.Bxe6 fxe6 30.a3 Rd6= 27.axb3 Bh6+ 28.Kb1² Qc6 29.Qf3 Kg7 30.Ncd5 Qe6 31.Bc5 Rh8 32.Nc4 Rc8 33.Bb6 Rh8 34.Rd1 Bg5 35.Nxf6 Nxf6 36.Rd6 Qe7 37.Qd3 Rb8 38.Bd8 Qe8 39.Bxf6+ Bxf6 40.Qd5 b5 41.Ne3 Rd8 42.Ng4 Rxd6 43.Qxd6 Qd8 44.Qxd8 Bxd8 45.Nxe5... 1-0 (64) 12.11 Jürgen Hess 2423 Anatoly Spirin 2330 ICCF email 2009 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 0-0 8.Qd2 Nc6 9.0-0-0 d5 10.Qe1 e5 11.Nxc6 bxc6 12.exd5 cxd5 13.Bg5 Be6 14.Bc4 Qc7 15.Bxf6 dxc4 16.Bxg7 Kxg7 17.h4!² Rab8 A) 17...Rad8 18.Rxd8 Rxd8 19.h5 g5 20.h6+ Kg6 21.g4²; B) Better is 17...h5 18.g4!?N (this novelty was already suggested by Amanov/Kavutskiy) 18...Rh8! 19.Nd5 Bxd5 20.Rxd5 (Black can’t cover his weaknesses across the board) 20...c3! (so, he sacrifices them! 20...Rae8 21.Qc3! hxg4 22.fxg4ƒ) 21.b3 Rad8 22.Rxe5 Rd4 23.Re4 Rxe4 24.Qxe4 Black is not mating with ...Qd6-a3, so White retains the better chances. 18.h5 Qb6 18...f6 is more solid, but 19.Ne4! Qb6 20.Qc3 Rfd8 21.Rxd8 Rxd8 22.hxg6 hxg6 23.Qa3 keeps control, as the open black king needs constant protection. 19.Na4! Qb5 20.Qe3 Bf5 21.h6+ Kg8 22.Qa3± Qb4 23.Qxb4 Rxb4 24.Nc3 This endgame is perfect for White, as Black’s bishop lacks potential and the h6-pawn ties up the king. 24...Rfb8 25.b3 Be6 26.a3! 26.Nd5 Bxd5 27.Rxd5 e4! 26...R4b6 27.b4 Kf8 28.Rhe1 Ra6 29.Kb2 f6 30.b5 Kf7 31.a4 Rab6 32.Ka3 a6 32...g5 33.Kb4 a6 34.Rd2 axb5 35.axb5+– 33.a5! Rxb5 34.Nxb5... 1-0 (50) 12.12 Reiner Nickel 2497 Detlef Rook 2448 ICCF email 2012 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 0-0 8.Qd2 Nc6 9.0-0-0 d5 10.Qe1 e5 11.Nxc6 bxc6 12.exd5 Nxd5 13.Bc4 Be6 14.Kb1 a5 15.h4!ƒ Rb8 A) 15...h5 16.Bc5 Re8 17.Ne4 a4 18.g4! hxg4 19.h5 doesn’t stop White; B) 15...Nxc3+ 16.Qxc3 Bd5 (Pirs-Neagu, email 2012) 17.Qd3!? (I like this move to clarify the tension) 17...Rb8! (17...Qc7 18.Bxd5 cxd5 19.Qxd5 Rfc8 20.Qe4 Rab8 21.c4 Rb4 22.Rc1 Rxc4 23.Rxc4 Qxc4 24.Qxc4 Rxc4 25.Rc1! Rxc1+ 26.Kxc1+–) 18.b3 Qc7 19.h5² Black’s position is playable, but I prefer White’s flank attack. 16.Ne4 f5 17.Ng5 Re8 17...Bc8 18.Bb3! and c2-c4. 18.b3 a4 18...Bc8!? is hard to refute: 19.Qd2 (19.Ne4!?) 19...h6 (19...a4 20.Qxd5+!) 20.Ne4 (20.Qxd5+=) 20...Kh7 21.Nc5 f4 22.Bf2 Bf5 23.Ne4! with an edge. 19.h5 axb3 19...gxh5 20.Nxe6 Rxe6 21.Rxh5ƒ 20.cxb3 Qf6 21.h6! Bh8 Now the bishop is stuck. 21...Bf8 22.Nxe6 Qxe6 was better. 22.Nxe6 Qxe6 23.Qa5 Red8 24.Rd2 Bf6 25.Rhd1± The central pressure breaks Black’s position. 25...Kh8 25...f4 26.Bb6 Rd7 27.Kc1!?± 26.Bxd5 cxd5 27.Rxd5 Re8 28.Rd6 Black resigned as the rook sacrifice isn’t a perpetual: 28...Rxb3+ 29.axb3 Qxb3+ 30.Ka1 e4+ 31.Rxf6 Qxd1+ 32.Kb2 Rb8+ 33.Rb6+– 12.13 Peter Leko 2709 Lawrence Trent 2463 Douglas 2016 (4) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 0-0 8.Qd2 Nc6 9.0-0-0 d5 10.Qe1 e5 11.Nxc6 bxc6 12.exd5 Nxd5 13.Bc4 Be6 14.Kb1 Re8 15.Ne4² Qc7 A) 15...f5 16.Ng5 a5 17.g4!? fxg4 18.Nxe6 Rxe6 19.fxg4ƒ; B) 15...Qb8 16.Bc1!?N (I like this retreat, to anticipate ...f7-f5/e5-e4. 16.Bc5 f5 17.Ng5 e4 18.Bb3 a5 19.Bd4 Bxd4 20.Rxd4 Qe5 21.Nxe6 Rxe6 22.Qd2 e3 23.Qd3 a4 24.Bxd5 cxd5 25.Rxd5 Qf6 26.Qd4 Qxd4 27.Rxd4 Raa6²) 16...a5 17.a3 h6 18.g4 a4 19.h4² Black’s queenside play is at an end; C) 15...a5 16.g4 a4 17.h4 h6 (17...Qa5 18.Qxa5 Rxa5 19.Bd2 Ra7 20.h5²) 18.Bc5 Qc7 19.h5 g5 20.Rh2² was a favourable structure in Siigur-Windhausen, email 2010, though the position was locked enough to draw in the end. 16.Bc5! h6 16...Nf4 17.Bxe6 Nxe6 18.Bd6 Qb6 19.g4 Rad8 20.Qc3! Nd4 21.Bc5 Qc7 22.Qe3± Savoca-Martynov, email 2013. 17.g4 Nf4 17...Red8 18.g5 h5 19.h4² is a nice structure for White, but an invasion to d6 was averted. 18.Bd6 18.Bxe6! Nxe6 19.Bd6 18...Qb6 Better was 18...Qc8 19.Bxe6 Qxe6². 19.Bxe6 Rxe6 20.Bc5 Qb5 21.b3± Black’s coordination is lacking here. 21...Ree8 21...a5 is blocked off with 22.a4. 22.h4! Qe2?! 22...Ne6 23.a4 Qb8 24.Bd6± 23.Qxe2 Nxe2 24.g5 h5 25.Rd6 The endgame looks winning as Black has too many weaknesses. 25.Rd7!? 25...a5 25...Rec8 26.Rd7 26.Rxc6+– a4 27.Re1 27.b4! 27...Nf4 27...Nd4 28.Bxd4 exd4 29.Rd1 axb3 30.cxb3+– 28.b4 a3 29.c3 Red8 30.Kc2 Ng2 31.Rh1 Bf8 32.Bb6 Rdb8 33.Bf2 Rd8 34.b5 Nf4 35.b6 Nd3 36.Rd1 1-0 12.14 Surya Shekhar Ganguly 2668 Renato Quintiliano Pinto 2484 Doha rapid 2016 (10) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 0-0 8.Qd2 Nc6 9.0-0-0 d5 10.Qe1 e5 11.Nxc6 bxc6 12.exd5 Nxd5 13.Bc4 Be6 14.Kb1 Rb8 15.Ne4 f5 16.Bxa7 Qe7 17.Bc5 Qb7 18.Bb3 fxe4 19.Bxf8 Rxf8 20.fxe4 Nf4 21.Qc3!± Bxb3?! 21...Kh8 22.Bxe6 Nxe6 23.Qb3 Qxb3 (23...Qe7 24.Rhf1 Rc8 25.Qc4±) 24.axb3 Ng5! seems the best try, but the minor pieces are still outpaced by the rooks: 25.Rhe1 c5 26.c3 Kg8 27.Rd5 Ne6 28.Rd6 Rf6 29.Red1 and Black is all bound up. 22.Qxb3+ Qxb3 23.cxb3! Ne6 24.Rhf1 Rc8 24...Nd4 25.Rxf8+ Bxf8 26.Rf1 Bh6 27.b4+– The a-pawn will be too fast here. 25.Rd6 Nc5 26.Rfd1+– Rc7 A) 26...Nxe4 27.Rd8+ Rxd8 28.Rxd8+ Kf7 29.Rd7+ Kg8 30.Kc2+–; B) 26...Bf8 27.Rd8 Rc7 28.b4 Ne6 29.Rb8 and charging the a-pawn will decide. 27.Rd8+ 27.b4! Nxe4 28.Rd7 Rxd7 29.Rxd7+– 27...Kf7 27...Bf8 28.Rf1 Rf7 29.Rxf7 Kxf7 30.a4+– 28.b4! Ne6 29.R1d7+ Rxd7 30.Rxd7+ Ke8 31.Ra7 31.Rb7! is faster, but by this point Black is helpless in any case. 31...h5 32.Kc2 Bf8 33.Kc3 Bd6 34.Kc4 Bc7 35.Ra8+ Bd8 36.a4 h4 37.Ra7 Bc7 38.a5... 1-0 (48) Chapter 13 The Richter-Rauzer without 8...Bd7 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 The Classical has long been in the shadow of the Najdorf because of White’s aggressive queenside castling set-up, but Black plays flexibly and it’s not easy to conclusively prove an advantage. 6.Bg5! negates both ...e7-e5 and ...g7-g6, at least one of which would be effective against most of White’s alternatives. Unusual sixth moves A) 6...h6?! 7.Bxf6 gxf6 weakens Black’s structure for no special reason, and after 8.Qd2 White might follow BrenkeSalceanu, email 2002; B) 6...e5? 7.Bxf6 gxf6 8.Nf5 Bxf5 9.exf5±; C) 6...Qa5?! loses too much time after 7.Bb5 Bd7 8.Nb3 Qd8 (8...Qb6 9.a4! a6 10.a5 Qd8 11.Be2 e6 12.0-0 was a miserable Scheveningen for Black in McClymont-Adly, Brisbane 2017; 8...Qc7 9.Qd2 e6 10.0-0-0 a6 11.Be2ƒ is likewise a good version of a normal position) 9.Qe2! e6 (9...a6 10.Bxc6 Bxc6 11.0-0-0± makes it hard for Black to get out of the e4-e5 break) 10.0-0-0 h6 11.Bh4 Be7 12.f4 Qc7, when White clearly has a Rauzer on steroids. I particularly like 13.Qd2!ƒ to set up Bxf6; D) 6...Qb6?! 7.Nb3 e6 8.Bf4! Ne5 (8...e5 9.Be3 Qd8 10.f3ƒ is a tempo-up English Attack) 9.Be3 Qc7 10.f4 Nc6 11.Qe2!? a6 12.g4!ƒ as in Moll-Karacsony, email 2010, is a clever way to punish Black’s dubious move order; E) 6...a6 7.Qd2 Nxd4 8.Qxd4 Qa5 ... is an uninspiring Najdorf/Rauzer hybrid. I like the rare 9.h4!? h6 (9...e5 10.Qd2 Be6 (or 10...Be7 11.Bc4ƒ) 11.Bxf6 gxf6 12.g3² is a poor man’s Sveshnikov) 10.Bd2 (compared to 9.Bd2, the h-pawn moves favour White) 10...Qc7 (or 10...e5 11.Qd3 Be7 12.0-0-0 Be6 13.Kb1 with a good English Attack after f2-f3 or f2-f4) 11.Nd5!N 11...Nxd5 12.exd5 Qxc2 Black’s position is strategically bad if he doesn’t accept the sacrifice, but now 13.Rc1 Qg6 14.Bxa6! is a painful tactical shot, with the point 14...bxa6? 15.Rxc8+ Rxc8 16.Qa4+ Kd8 17.Ba5+ Rc7 18.0-0 and Qc6 will prompt Black’s resignation; F) 6...g6!? 7.Bxf6 exf6 looks ridiculous, but White must be accurate to neutralise Black’s bishop pair: 8.Bb5 Bd7 9.Qd2 Bg7 10.0-0-0 0-0 11.Nb3! a6 (11...Be6 12.Qxd6 Qb6 13.Qc5 Bh6+ 14.Kb1 Bxb3 15.Qxb6 Bxa2+ 16.Nxa2 axb6 17.c3 left White with the better structure in Schröder-Naroditsky, Helsingor 2015, though 17.c4!? is also possible) 12.Bxc6 Bxc6 13.f3 a5 14.Qxd6 Black didn’t have enough compensation for the pawn in Studer-Gähwiler, Doha 2014 (14.a3!? to keep control might be even better). 14...Qxd6 15.Rxd6 a4 would have at least required White to find the right square for his knights, though: 16.Nc5! a3 17.Nd5! axb2+ 18.Kb1 with an initiative. The ancient 6...Bd7 6...Bd7 is an old-school line that requires a good understanding of the Bxf6 gxf6 structure. 7.Qd2 A) 7...a6 tries to reach the ...a7-a6/ Bd7 main line while avoiding 6...e6 7.0-0-0 a6 8.Nxc6, but 8.f4!? e6 9.Nf3 h6 10.Bh4 b5 11.e5 dxe5 12.fxe5 b4 13.Ne2 Ne4 14.Qf4 Ng5 15.Bxg5 hxg5 16.Nxg5 f6 17.exf6 gxf6 18.Ne4 f5 19.Nd6+ Bxd6 20.Qxd6² shows that no move order trick comes for free in chess; B) 7...h6 8.Bxf6 gxf6 9.0-0-0 (9.Bb5!? is interesting, but I’d rather stick to an established route to a white plus) 9...Nxd4 10.Qxd4 Qa5 (as Negi notes, White should not confuse this with a normal Rauzer, as Black hasn’t played ...e7-e6 yet. The battle will revolve around who can get a pawn to f5) 11.Kb1!? (a tiny refinement to dodge ...Rg8 plans) 11...Rc8 (11...Rg8 12.Nd5! stops ...Bg7 because of Nxe7 tricks, and if 12...Rc8 13.f4 (Noble-Ruano Lopez, email 2008) 13...f5 14.e5 Rg6 15.Be2! Bg7 16.Bf3 retains White’s central pressure) 12.f4 – see 7...Rc8; C) 7...Nxd4 8.Qxd4 Qa5 9.f4 will be addressed in Ding-Bu, China tt 2016. I’ll just note for now that 9...e6 10.0-0-0 Be7 11.e5 dxe5 12.fxe5 0-0-0! (12...Bc6? 13.Bb5! Bxb5 14.exf6 Bc6 15.Ne4! Rd8 16.Qe3+–) 13.Qf4 Nd5 14.Nxd5 Bxg5 15.Qxg5 exd5 16.a3 g6 17.Qf4 Rhe8 18.Bd3 Re7 19.Rhe1 is marginally better for White, as Black’s pawns and bishop occupy the same colour complex; D) 7...Rc8 8.0-0-0 (most books recommend 8.f4, so I want to show that the old main line is just as good) 8...Nxd4 (8...h6 9.Bxf6 gxf6 is less effective than after 8.f4... ... because of 10.Nf5! Qa5 11.Bd3± and Black struggles to continue his development, as 11...e6?! fails to 12.Nxd6+! Bxd6 13.Bb5) 9.Qxd4 Qa5 10.f4 and now: D1) 10...e5 11.fxe5 dxe5 12.Qd2 Bc6 13.Bxf6 gxf6 14.Qf2 was awful for Black in Dvoirys-Smirin, Leningrad 1990; D2) 10...Qc5?! 11.e5 Qxd4 12.Rxd4 Ng4 13.exd6± is not what Black wants; D3) 10...e6 can transpose to 8.f4 lines after 11.e5, but I like 11.Kb1! Qc5 (11...Bc6?! 12.Bxf6 gxf6 13.Qxf6 Rg8 14.Qh4 is just an extra pawn for White) 12.Bxf6 gxf6 13.Qxf6 Rg8 14.Qh4 White is up a pawn and can return his material to switch the attack to Black’s king. 14...b5 (14...h6 gets hit by 15.e5!N) 15.Bd3 b4 16.Nd5! exd5 17.exd5 Qxd5 18.Ba6 Be7 19.Qxe7+ Kxe7 20.Rxd5+– is a sterling variation; D4) The objectively best 10...h6 11.Bxf6 gxf6 12.Kb1 Qc5 13.Qd3² will be addressed in Pirs-Sekretaryov, email 2012, where I summarise Negi’s extensive analyses; D5) The exchange sacrifice 10...Rxc3 puts a lot of players off 8.0-0-0, but I believe White obtains a clear advantage with a bit of homework: 11.bxc3 e5 (11...Qxa2? 12.e5+–) 12.Qb4! Qxb4 13.cxb4 Nxe4 14.Bh4 Black scores well in practice, so it’s important to remember the following lines to prove our advantage. 14...g5 (14...f6 is a bit slow and we can anticipate ...Nc3 with 15.a3! Be6 16.Re1 Nc3 17.Bd3±; after 14...f5 15.fxe5 dxe5 16.a3± White can follow Roberts-Sheers, email 2014; 14...Nc3?! 15.Rd3 Nxa2+ 16.Kb2 Nxb4 17.Rb3 a5 18.c3 Nc6 19.Rxb7 f6 20.Bb5 Kd8 21.fxe5+– is already a decisive initiative for White, as Black didn’t yet develop his kingside) 15.fxg5 Be7 16.Bc4! We should not try to consolidate our material passively – fighting for the initiative is essential here! 16...h6 (16...b5 17.Rde1!N 17...bxc4 18.Rxe4± is poor for Black) 17.Rhf1 Be6 (17...0-0 can be met in several good ways. I like 18.Rd3!?N 18...hxg5 19.Be1 b5 20.Bd5 Nf6 21.Bb3± when White can switch to targeting the kingside with Bd2 or h2h4) 18.Bxe6 fxe6 19.c4! (it is important to keep Black’s centre at bay) 19...hxg5 (19...Kd7 20.Kc2 hxg5 21.Bg3 Rc8 22.Kb3 Nxg3 23.hxg3± is similar) 20.Bg3 gave White wins in two correspondence games – after 20...Nxg3 21.hxg3 Kd7 22.Kc2 it is hard for Black to find the counterplay essential to holding an exchange-down position. 6...e6 7.Qd2 without 7...a6, 7...Be7 6...e6 7.Qd2 A) 7...Bd7? loses a pawn to 8.Ndb5+–; B) 7...h6 8.Bxf6 gxf6 9.0-0-0 a6 10.f4 move orders White into the Rauzer structure, which we avoid with f2-f3, but White is a tempo up on the usual version. 10...Bd7 (10...h5 11.Nxc6!? bxc6 12.Bc4 Rb8 13.Bb3 Qb6 14.Kb1 Be7 15.f5!± gives White powerful pressure, while it’s hard for Black to hit back because of White’s superior development; 10...Qb6 11.Nb3 Bd7 12.Be2 h5 13.Kb1 0-0-0 transposes to 10...Bd7) 11.Kb1 (this move tends to work best when we’re waiting to see Black’s set-up) 11...Qb6 (11...Qc7 12.f5! favours White, see Mazur-Bednar, Slovakia tt 2013) 12.Nb3 0-0-0 13.Be2 h5 14.Rhf1 White is fully mobilised and it is difficult for Black to engineer counterplay because he castled queenside. Nonetheless, it’s quite rare for White to find the best way forward from this point. For what it’s worth, Negi reaches this position in his repertoire book, but with the king on c1 instead of b1. 14...Kb8 (14...Be7 15.Na4! Qa7 16.h4!N is a powerful positional plan, fixing the h5-pawn as a weakness. After 16...Rdg8 17.Bf3 Kb8 18.a3± White can keep improving his position, while Black is reduced to shuffling) 15.Rf3!, intending Rh3 to pressure the weak h5-pawn. B1) 15...Bc8 16.Rh3 h4 17.Qe1 Be7 is a deliberate pawn sacrifice, but we can keep up the pressure with 18.a3!N as Black can hardly improve his position, e.g. 18...Qc7 19.f5! Rdg8 20.Bf3± and White is ready to win the h4-pawn without permitting the freeing ...f6-f5; B2) 15...Be7 16.Rh3 (16.h4!? Rdg8 17.g3±, as in Saule-Weber, email 2005, may be even stronger) 16...h4 17.Qe1 Rc8 White has taken on h4 in practice, but he should first stop counterplay with 18.Bf3! Qc7 19.a3±, and take on h4 only when ...f6-f5 is not following; B3) 15...h4 16.Qe1 Ne7 (16...Rg8 17.Qf1! is a flexible way to cover g2, and after Rh3 Black will probably need to return with his rook in any case) 17.Rfd3 Ng6 18.Qf1² Despite the knight manoeuvre, it’s hard for Black to harmonise his pieces, while White can improve his position with either a2-a4-a5 or a2-a3/g2-g3/Nd4; C) 7...Qb6 8.Nb3 Be7 (8...a6 9.0-0-0 Qc7 10.f4 b5 11.Kb1 b4 12.Bxf6 gxf6 13.Ne2 is positionally great for White, as you can witness in Sadvakasov-Jumabayev, Astana 2007) 9.0-0-0 0-0 (9...a6 10.Kb1 0-0 11.h4 just transposes) 10.Kb1 White has an improved version of 7...Be7 8.0-0-0 0-0, as 9.Nb3 is a serious move in that position, whereas Black will have to play ...Qc7 to prepare his typical ...a7-a6/ ...b7-b5 counterplay. C1) 10...a6 11.h4! Rd8 (or 11...Ng4 12.Bxe7 Nxe7 13.Qg5 Nf6 14.f3ƒ) 12.g4N gives White too rapid an attack with Bxf6/g4-g5, as White has dispensed with the preparatory f2-f3; C2) 10...Rd8 11.h4 d5 (11...a5 and ...a5-a4 can be covered by 12.Bb5!²) 12.exd5 Nxd5 13.Nxd5 Rxd5 14.Bd3 Despite freeing himself in the centre, Black remains under pressure as White’s pieces are more active. Kingside development 7...Be7 8.0-0-0 8...0-0 (other moves are likely to transpose elsewhere in the chapter, as in the case of 8...Nxd4 9.Qxd4 0-0 10.f4 or 8...a6) 9.f4! Conversely, 9.f3 was recommended in the previous edition, but the English Attack approach is less effective when Black can play the bishop to b7 rather than d7. On the other hand, I haven’t found a route to equality against either my recommendations or Negi’s: A) 9...Bd7 10.Ndb5 d5 11.exd5 Nxd5 12.Nxd5 exd5 13.Bxe7!?N (13.Qxd5 Bg4 14.Qxd8 Bxd8 15.Rd2 Bb6! 16.Be2 Be6 is less clear, though probably still a bit better for White after 17.f5!?N 17...Bxf5 18.Bf4 as Nd6 is nettlesome) 13...Nxe7 14.Be2² and Rhe1 gives some pressure against the IQP; B) 9...e5 (if Black has to commit his structure like this, it’s a sign his position has become unpleasant) 10.Nf3 exf4 (or 10...Bg4 11.Be2 Rc8 12.Kb1 Bxf3 13.gxf3± Koch-Gonzalez Sole, email 2011) 11.Bxf4 Be6 12.Kb1 Rc8 13.Be2 Re8 and Black held the position in an elite correspondence game Wunderlich-Dothan, email 2006, but an improvement is 14.Rhe1!? h6 15.a3² – White has more space, so he can patiently improve his position. Black can’t take forever with his counterplay either, as h2-h3/g2-g4-g5 will pry open the kingside and d6 is perennially weak; C) 9...d5 10.e5 Nd7 11.h4² doesn’t require special analysis, as White has an improved version of the Steinitz French. Hansen-Hirneise, Hofheim 2017, is one instructive example; D) It’s hard to improve on Negi’s answer to 9...a6?!: 10.e5! dxe5 (10...Nd5 11.Nxc6 bxc6 12.Bxe7 Qxe7 13.Ne4 dxe5 14.fxe5 transposes) 11.Nxc6 bxc6 12.fxe5 Nd5 13.Bxe7 Qxe7 14.Ne4 with a clear positional advantage. For example: 14...Qc7 (Black struggles to free himself: 14...c5?! 15.c4 Nb6 16.Qe3±) 15.Nd6!N 15...f6 16.Bd3 fxe5 17.Nc4 with a pleasant hold on the position for a pawn; E) 9...h6 10.h4 is likely to transpose to 9...Nxd4. If Black tries to avoid the exchange, he runs into problems: 10...Bd7 11.Ndb5 d5 12.Bxf6 Bxf6 13.exd5 Nb4 14.dxe6 Bxe6 15.a3 Na2+ 16.Nxa2 Bxa2 17.g4²; F) 9...Nxd4 10.Qxd4 and now: F1) 10...h6 11.h4 can transpose to 10...Qa5 after 11...Qa5 12.Kb1. Black’s alternatives don’t really impress me: 11...hxg5 (this is exceedingly risky. 11...b5!?N 12.Bxb5 Bb7 is the engine’s recommendation, but it accepts a worse endgame with 13.Bxf6 Bxf6 14.Qxd6 Bxc3 15.Qxd8 Rfxd8 16.bxc3 Bxe4 17.Rxd8+ Rxd8 18.Rg1 Kf8 19.g3² where a doubled extra pawn is still a pawn!) 12.hxg5 Ng4 13.Be2 e5 14.Qg1 exf4 15.Bxg4 Bxg5 16.Bf5!?N (16.Bxc8 Rxc8 17.Kb1ƒ also favours White with the h-file attack, see Shengelia-Danner, Oberwart 2010) 16...Bxf5 17.exf5 Rc8 18.Kb1 Re8 Black can block Qh2 with ...Bh6, but 19.Rh5! Bh6 20.Qxa7ƒ leaves White with the dominant minor piece and safer king for free; F2) 10...Qa5 Black wants to keep his options open, depending on White’s set-up. 11.Kb1 F21) 11...h6 12.h4! Often the most ambitious moves are rewarded against the Sicilian. F211) You don’t need to be a computer to see that accepting the poisoned bishop with 12...hxg5?? 13.hxg5 Ng4 14.Be2 e5 15.Nd5! Qd8 16.Qd3 leads to a swift demise; F212) 12...Rd8 is the main move, but I have almost refuted it with 13.Qe3 Bd7 14.Bd3 Bc6 15.Qe2!N, preparing e4-e5 as well as a later g2-g4-g5: F2121) 15...b5 16.g4 Rac8 (16...Kf8 17.Qg2!± sets up Bxf6, Ne2 and g4-g5 to open the kingside) 17.Nxb5 Rb8 18.Nd4 Qb6 19.Nb3± is just an extra pawn for White; F2122) 15...Kf8 16.Rdf1! Ke8 17.f5 pries open the kingside: 17...hxg5 18.hxg5 Kd7 19.gxf6 Bxf6 20.Rh7! gives White an initiative after 20...Bxc3 21.fxe6+ fxe6 22.Rf7+ Kc8 23.bxc3 Qxc3 24.Rhxg7² and the blind pigs on the seventh pack a punch; F2123) 15...Rd7 16.g4 Re8 17.Rh3! a6 18.Rf1± and White is ready to pawn storm with Bxf6, e4-e5 and g4-g5, for a nearly decisive attack. F213) The counterattack 12...e5!? calls for inventive play from White: 13.Qf2 exf4 14.Nd5! (the initiative is everything here) 14...Qd8 (14...Nxd5 15.Rxd5 Qc7 16.Qxf4! Be6 (16...Re8?! fails to 17.Bxh6!) 17.Bxe7 Qxe7 18.Rxd6 (Balogh-Zelcic, Austria Bundesliga 2003/04) 18...Qxd6 19.Qxd6 Rad8 20.Qd3 Rxd3 21.Bxd3 is a pawn up endgame) 15.Bxf4!N 15...Nxd5 16.exd5 Bf6 17.Re1! (White anticipates ...Bg4, but is also ready to place his bishop on the ideal d3-square) 17...Bf5 18.Bxh6 Qb6 19.Qxb6 axb6 20.Bg5 Rfc8 21.Bd3 Bxd3 22.cxd3 Be5! White’s extra pawn may not look like much, but with 23.g4 (23.Re4!? is also promising) 23...Ra5 24.Be3 g6 25.d4 Bh8 26.h5! White can preserve some initiative. F22) I’ve made 11...h6 the main line because of the possible transpositions with an earlier ...h7-h6, but I found 11...Rd8 trickier to meet, as now the h2-h4 plan is less effective: 12.Be2! (White should change plans against ...Rd8, as 12.h4 Bd7 13.Bd3 Bc6 14.Qe3 Kf8!= demonstrated the advantage of avoiding ...h7-h6, and was objectively fine for Black in Almasi-Jobava, Reggio Emilia 2009) 12...Bd7 (12...h6 13.Bh4 e5 14.Qd3!N is a deep computer idea: 14...exf4 15.Be1 Qe5 16.g3 Be6 17.gxf4 Qxf4 18.h4! Qe5 19.Bg3 Qc5 20.Nd5 Bxd5 21.exd5 Nd7 22.Qf5! Bf6 23.c3 and White’s kingside attack is considerably faster) 13.Rhf1 Bc6 (13...Rac8 14.Bh4! Bc6 15.g4ƒ is a tough attack to parry) 14.f5 Rac8 15.Qe3!?² White had kingside pressure in Turov-Rubio Doblas, email 2010, while Black’s queenside threats have yet to appear. Introduction to 7...a6 7...a6 Compared to the 6.Bg5 Najdorf, Black can’t play ...b7-b5 as quickly because of the knight tension, but White also doesn’t have the ideal f2-f4/Qe2(f3)/0-0-0 set-up. 8.0-0-0 Now Black must show his cards. 8...h6 A) 8...Bd7 is the main line, and will be the subject of the next chapter, as my recommendation 9.f3 can become confusing initially from the multitudinous transpositions; B) 8...Nxd4 9.Qxd4 Be7 10.f4 b5 11.Bxf6 gxf6 transposes to 8...Be7; C) 8...Be7 is a tricky move order, but we can be crafty too! 9.Bxf6!? gxf6 10.f4 Nxd4 (10...Bd7 11.Kb1 b5 12.Nxc6 Bxc6 13.Bd3± is one of the best versions of the Rauzer structure for White, as noted in Movsesian-Hou, KhantyMansiysk 2011) 11.Qxd4 b5 (this normally arises via 9.f4 Nxd4 10.Qxd4 b5 11.Bxf6 gxf6, but we have avoided a couple of options such as 10...0-0) 12.Kb1!? (Negi covers 12.e5, but you’ve probably noticed by now my tendency to go my own way, in this case with the f4-f5 break, but I’d like to keep Black guessing for one more move) 12...Qc7 13.f5 Taking on f5 would destroy Black’s structure: C1) 13...Bd7 14.Ne2! still works well, e.g. 14...0-0-0 (14...0-0 15.Nf4 Kh8 16.Qf2 Rg8 17.Be2± places White’s pieces ideally to exploit Black’s weak kingside with Bh5; 14...Rc8 15.Qd2 Bf8 16.c3 h5 17.fxe6 fxe6 18.Nd4 meanwhile is a bit sad for Black, who will feel the heat in the centre) 15.g3 Kb8 Despite the engine’s highly favourable evaluation, Black held the draw comfortably in Goncharenko-Fischer, email 2013. I propose 16.Bh3!?, pressuring e6 to provoke 16...e5 17.Qd2 with the dream position for White; C2) 13...Qc5 14.Qd2 Bd7 15.Ne2!ƒ We will see in Jensen-Zmokly, email 2010, that Black’s position is very passive and hard to defend. 9.Nxc6! Transforming the structure gains in strength when Black has spent tempi on the rook’s pawn moves. 9.Be3 seems to be better for White too, but it requires much more work to prove. As a starting point, I’ll note that the main line 9...Be7 10.f3 Nxd4 11.Bxd4 b5 12.Kb1 Rb8 is coming under serious pressure from 13.g4! b4 14.Ne2 e5 15.Bf2 Be6 16.Ng3 Qa5 17.b3 d5 18.Nf5 Bxf5 19.exf5±, as in Fischer-Gajarsky, email 2010. 9...bxc6 10.Bf4 d5 11.Qe3!² White must be quite precise due to Black’s strong centre, but he’ll be rewarded with a persistent attack and initiative. 11...Bb4 12.Be2!? It is easier to remember our lines when we play Be2 against everything! The alternatives are: A) 11...Qa5 12.Be2 dxe4 (12...Bb4 will be covered under 11...Bb4; 12...Bb7 13.Qg3!? makes it hard for Black to develop the kingside, but 13...0-0-0!? 14.Kb1! d4 15.e5 Ne8 16.Ne4± is not a panacea) 13.Nxe4! Nd5 14.Qg3 Qxa2 White has three moves for a clear edge – I’ve gone with 15.Be5!±, when even in Branding-Walsh, email 2005, one of the world’s strongest correspondence players of the time was unable to defend against White’s central attack; B) 11...Be7 12.Be2 0-0 (12...Bb7 13.Qg3 Kf8 14.Bc7 Qc8 15.Be5 made it difficult for Black to untangle in HungaskiAung, Wheeling 2011; 12...Nd7 13.h4 0-0 transposes to 12...0-0) 13.h4 – Black must be ready for both Bxh6 and g2g4-g5: B1) 13...Qa5? meets a thematic sac: 14.Bxh6! gxh6 (14...Nxe4 15.Nxe4 dxe4 16.Qg3 Bf6 17.Kb1 Prokopp-Kuznetsov, email 2001, keeps Black’s queenside in lockdown) 15.Qxh6 The following line is semi-forced: 15...Nh7 16.exd5N 16...cxd5 17.Rh3 Kh8 18.Rg3 Rg8 19.Bd3 f5 20.Rxg8+ Kxg8 21.Qg6+ Kh8 22.Bxf5 exf5 23.Qc6 Rb8 24.Qe8+ Nf8 25.Qxe7 Be6 26.Qf6+ Kh7 27.b3 Black’s king is too exposed for his position to be playable; B2) 13...Nh7? 14.g4! Bxh4 15.Kb1 Bg5 16.Bxg5 Qxg5 17.f4 Qe7 18.g5 d4 19.Qxd4 e5 20.Qa4 exf4 21.gxh6 g5 22.Qxc6± was the brutal course of the game Edouard-Raetsky, Al-Ain 2012; B3) 13...Re8 14.g4 Nd7 15.Qg3 e5 16.Bd2 is a surprisingly common sequence – Black seems to be just lost. See Fagerström-Dzenis, email 2009; B4) 13...Nd7 14.Kb1!N is a nice novelty by Negi, waiting to see Black’s plan: B41) After 14...Bc5 15.Qg3 Qf6 16.f3 it is hard for Black to avoid the coming kingside pawn storm, for example: 16...a5 (16...Bb4 17.Na4 e5 18.Bc1 d4 19.Qh2² is similar) 17.Na4 Be7 18.Qh2! e5 19.Bc1 Qe6 20.g4 and h6 is a vital hook for White’s attack; B42) 14...Qb6 15.g4! d4 16.Qxd4 Qxd4 17.Rxd4 e5 18.Rxd7 Bxd7 19.Bxe5 Rfe8 20.f3 White’s edge may be even greater than Negi originally noted: 20...a5 (or 20...Be6 21.Na4 Rad8 22.Bd3±) 21.Na4! Bxh4 22.Bxg7 Kxg7 23.Rxh4 f5 24.gxf5 Bxf5 25.Bd3 Bg6 26.Kc1± 12...0-0 12...Qa5 looks threatening... ... but after 13.Be5! it will be White calling all the shots: A) 13...dxe4 14.Qg3! Bxc3 15.Bc7! Bxb2+ 16.Kxb2 Qb4+ 17.Ka1 Nd5 18.Qxg7 Qf8 19.Qd4! Bd7 20.Bg3+– and c2c4 was a fine piece of opening preparation in Ponomariov-Bu, Lausanne 2001; B) 13...Be7 14.exd5 cxd5 15.h4 Bb7 16.Rh3 Qc5 17.Qf4 Rc8 18.Rg3 will deprive Black of the right to castle. See Miciak-Belak, email 2010; C) 13...Bxc3 14.Bxc3 Qxa2 15.Bd3 (Black is up a pawn, but can hardly develop) 15...dxe4 16.Qg3! exd3 17.Qxg7 Rg8 18.Qxf6 White has a decisive attack with the opposite-coloured bishops, as we’ll see in Ivanov-Perez, email 2012, in the games section. 13.e5 Nh7 This is necessary to guard against Bxh6 motifs. 13...Nd7 14.Qg3 Kh8 15.Qh3 Black has mostly been getting cleaned up from this position: A) 15...Kh7 16.Bd3+ Kg8 17.Ne2! Qc7 18.Bxh6!+– was already crushing in Sivic-Larsen, corr 2010; B) 15...Be7 16.Bxh6! gxh6 17.Qxh6+ Kg8 18.h4 Nxe5 19.Ne4 f5 20.Rh3 f4 21.Ng5 Rf7 22.Nxf7 Nxf7 23.Qg6+ Kf8 24.Bh5 Qe8 25.Rc3+– is a similar story – many correspondence players have reached this point only to find Black is utterly defenceless against White’s attack; C) 15...Bxc3 16.Qxc3 Qb6 17.Qh3! Qxf2 18.Bf3 (the stock Bxh6 threat already forces drastic measures from Black) 18...Nxe5 19.Rd2 Qc5 20.Bxe5 f6 21.Bg3 e5 22.Qh5 Rb8 23.Rd3 Be6 24.Rc3± White converted his material advantage in the model game Noble-Gaysin, email 2012. 14.Ne4 Alternatively, 14.a3 Be7 15.h4² gave White the initiative in Gerasimov-Novak, email 2013. 14...Qh4!? 14...f5 15.Nd6 Ng5 16.h4N 16...Ne4 17.Nxe4 fxe4 18.Qg3 Kh8 19.f3! opens the kingside in White’s favour, with the idea 19...exf3 20.Bd3! with an attack. 15.a3 Ba5 16.g3 Qe7! 17.Nd6 Bc7 The correspondence player Novak held two draws from here, but an improvement is... 18.h4! f6 19.Nxc8 Raxc8 20.Bd3!² ... keeping some pressure with the bishop pair. Summary 2...d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5: 6...g6 – +0.40 6...Bd7 – +0.45 6...e6 7.Qd2 Be7 8.0-0-0 0-0 9.f4 Nxd4 10.Qxd4: 10...h6 – +0.35 10...Qa5 – +0.30 7...a6 8.0-0-0: 8...Be7 – +0.45 8...h6 – +0.40 13.1 Reinhard Moll 2587 Zsolt Karacsony 2585 ICCF email 2010 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Nc3 d6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 Nf6 6.Bg5 Qb6 7.Nb3 e6 8.Bf4 Ne5 9.Be3 Qc7 10.f4 Nc6 11.Qe2 a6 12.g4 b5 13.g5 Nd7 14.0-0-0 Nb6 A) 14...Rb8 15.Kb1 b4 16.Na4 Nd8 17.Nd4ƒ; B) 14...b4 15.Na4 Bb7 16.Qf2! shows up the b6 sore point: 16...Na5 17.Nb6 Nxb3+ 18.axb3 Nxb6 19.Bxb6 Qc6 20.Bc4!± and taking on e4 just opens the attack to Black’s king; C) 14...Bb7 15.a3! Nc5 16.f5 Be7 17.Bh3 Nxb3+ 18.cxb3 Bc8 19.Kb1 steamrolled Black off the board in Sukhodolsky-Kashlyak, email 2011; D) 14...Be7 15.Kb1 Nb6 (15...Bb7 16.a3 b4 17.axb4 Nxb4 18.h4 0-0 19.h5+– Fedorov-Addis, email 2011) 16.Qf2 Rb8 17.Bd3 Na4 18.Ne2± (and f5) leaves the a4-knight out on a limb. 15.a3 15.Qf2!? Rb8 16.Kb1± 15...Nc4 16.Bf2 16...Rb8 16...h6 17.g6!? is a typical sac to lever open the kingside: 17...fxg6 18.a4! bxa4 19.Nxa4± 17.Kb1 h6 18.gxh6 Rxh6 19.h4± Be7 20.Qg4 Kf8 21.h5 f5 21...Bf6 loses to the breakthrough 22.e5! dxe5 23.Rg1 exf4 24.Bc5+ Kg8 25.Bxc4 bxc4 26.Bd6+–, regaining the material with interest. 22.exf5 Bf6 22...exf5 23.Qf3 23.Rh3 exf5 24.Qe2 Qe7 25.Qf3 Bb7 26.Qg3 Qf7 27.Bg2 Nd8 28.Bxb7 Rxb7 The engine feels Black can hold, but I haven’t found a clear improvement for him, so it seems his king is just too weak to hold. 29.Bd4! Ne6 30.Qf3 Re7 31.Bxf6 Qxf6 32.Rg3 Qf7 33.Nd5 33.Qa8+ Re8 34.Qxa6 Nxf4 35.Qxb5 Nxh5 36.Rg5± 33...Rb7 34.Rg6! Rxg6 35.hxg6 Qxg6 36.Re1 a5 37.Ne3 Re7 38.Nxc4 bxc4 39.Nxa5 Nc7 40.Rxe7 Kxe7 41.Nxc4 Qg1+ 42.Ka2+–... 1-0 (56) 13.2 Noel Studer 2395 Gabriel Gähwiler 2334 Doha 2014 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 g6 7.Bxf6 exf6 8.Bb5 Bd7 9.Qd2 Bg7 10.0-0-0 0-0 11.Nb3 a6 12.Bxc6 Bxc6 13.f3 a5 14.Qxd6 Qc8?! Better was 14...Qxd6 15.Rxd6 a4. 15.Nd4 15.g4!? is strongest, to prevent 15...f5. 15...f5 16.Nxc6?! 16.exf5 Bxd4 17.Qxd4 Qxf5 18.h4± 16...bxc6 17.e5 Qb7 18.f4? 18.Rhe1± is a better way to cover e5. 18...Qb4? This loses two tempi for nothing. 18...Rfb8 19.Na4 Bf8 20.Qd4 c5 21.Qc4 Qb4 22.Qxb4 Rxb4 23.b3 Rxf4 24.Nb6 Rb8 is messy but balanced. 19.Rd4! Qb7 20.Rc4 Rac8 21.Rd1+– Of course, Black’s structure is losing without compensating activity. White took it easy and won on the 67th move. 13.3 Mark Frederick Noble 2511 Martin Ruano Lopez 2123 ICCF email 2008 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 Nf6 4.Nc3 cxd4 5.Nxd4 Nc6 6.Bg5 Bd7 7.Qd2 Nxd4 8.Qxd4 h6 9.Bxf6 gxf6 10.0-0-0 Qa5 11.Kb1 Rg8 12.Nd5 Rc8 13.f4² Qc5 14.Qd3! a5 If 14...Bg7, 15.f5! traps the bishop, but on 14...h5 15.g3 h4 16.Be2 a6 17.b4 Qc6 18.c4± also kept Black’s pieces out in Lizorkina-Cardoso Garcia, email 2014. 15.g3 b5 16.c3 h5 17.Be2 Bg7 18.f5!± The weakness of h5 ensures Black’s position is strategically unplayable, since the opening of the queenside favours White. 18...Rh8 19.Qf3 19.h4!? 19...Bf8 20.h4 Qa7 21.Rd4 b4 22.Rc4 Rxc4 23.Bxc4+– Black is playing without his f8-bishop and rook. 23...Qc5 24.Bb3 Bh6 25.cxb4 axb4 26.Qxh5 Qd4 27.Qd1 Be3 28.Qf3 Bh6 29.Rd1 Qc5 30.e5 fxe5 31.f6 e6 32.Nxb4 Kd8 33.Qa8+ Qc8 34.Qa3 Qc5 35.Ba4 Bc8 36.Nc6+ Kc7 37.Qxc5 dxc5 38.Nxe5... 1-0 (68) 13.4 Ding Liren 2777 Bu Xiangzhi 2719 China tt 2016 (15) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 d6 6.Bg5 Bd7 7.Qd2 Nxd4 8.Qxd4 Qa5 9.f4 h6 A) 9...Rc8 transposes to 7...Rc8 after 10.0-0-0; B) 9...e5 10.Qd2 Be7 11.0-0-0 Bc6 12.Kb1 Qc5 13.Bxf6 Bxf6 14.f5ƒ is a passive version of the Rauzer structure for Black; C) 9...e6!? 10.0-0-0 Bc6 looks interesting until you notice 11.Bxf6 gxf6 12.Nd5!±. 10.Bxf6 gxf6 11.b4!? 11.0-0-0 transposes back to 7...h6, but where we played 11.f4 instead of my recommended 11.Kb1 (though it is likely to transpose anyhow). 11...Qb6 Black can’t entertain 11...Qc7?! 12.Nd5! Qxc2? 13.Bd3+–; and 11...Qd8 12.Nd5 Bg7 13.f5 e6 14.Ne3 is also passive for Black. 12.Qxb6 axb6 13.Nd5! Ra3 14.Bc4?! 14.0-0-0 Rxa2 15.Bc4 Ra4 16.c3!? (16.Bb3) 16...b5 17.Nc7+ Kd8 18.Nxb5 gives White good control of the position. 14...f5? 14...b5! 15.Bb3 Bc6 is not so clear. 15.exf5 Bxf5 16.0-0-0± Now White has full control of the position – the opening of the position favours the better developed side. 16...e6 17.Kb2 Ra7 18.Rhe1! Be7 18...Kd7 19.Bb5+ 19.Nxb6+– Kd8 20.a4 d5 21.c3 Bg4 22.Be2 h5 23.h3 Bf5 24.Nxd5... 1-0 (35) 13.5 Matjaz Pirs 2539 Roman Sekretaryov 2455 ICCF email 2012 1.e4 c5 2.Nc3 Nc6 3.Nf3 d6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 Nf6 6.Bg5 Bd7 7.Qd2 Rc8 8.0-0-0 Nxd4 9.Qxd4 Qa5 10.f4 h6 11.Bxf6 gxf6 12.Kb1 Qc5 13.Qd3 It’s hard to improve on Negi’s analyses of this position in Grandmaster Repertoire: 1.e4 vs. the Sicilian II, where he demonstrates Black’s difficulty in playing a reasonable pawn break. 13...f5 This is the break Black would like to play. A) 13...h5!? 14.Be2 h4 tries to avoid the h-pawn being fixed as a target, but the problem is that White hasn’t had to play f4-f5, and can stay flexible with 15.Nd5 Bg7 16.Rhf1 a5 17.c3 b5 18.a3² when Black must fear the e4-e5 break as White’s pieces are much better placed for the opening of the position; B) 13...e6 14.Be2 h5 15.Rhe1 h4 16.Bf3 Be7 17.f5 leaves Black very passive. White can increase the light-square pressure with Bg4 and Ne2-d4; C) 13...Bg7 14.f5 h5 (14...Qe5 can be met with 15.g3!?N and Nd5/Bh3 to clamp down on the light squares) 15.Qf3 (the key motif to remember is the Bb5/Rd5 trick) 15...Bc6 (15...h4 16.Bb5 Bc6 17.Bxc6+ bxc6 18.e5! As John Cox memorably put it once in a book, ‘it’s better to be right than original’, and the same ideas apply here as after 15...Bc6; 15...a6 is met by 16.Bd3, Rhe1 and Nd5, as Negi already indicated. As usual, the pressure on Black’s centre makes ...e7-e6 unpalatable) 16.Bb5 Kf8 17.Bxc6 bxc6 18.e5! was already noted by Negi, as none of Black’s captures work: 18...d5?! A) 18...dxe5 19.Rd3 Qa5 20.Rhd1 Bh6 21.Qxh5±; B) 18...Qxe5 19.Nd5! e6 20.Rhe1 Qxf5 21.Qxf5 exf5 22.Ne7 The endgame is probably a technical win after 22...Re8 23.Nxf5 Re6 24.Nxd6±; C) 19.e6± Gajwa-Henriquez Villagra, Bhubaneswar 2016. 14.exf5 Bxf5 14...Qxf5 15.Qd4 picks up a pawn. 15.Qg3 Be6 15...Qb6 16.Rd5 Rc5 17.Bd3 (Matsenko-Gutenever, Kurgan 2010) 17...Bd7 18.Rxc5 Qxc5 may be best, but White retains pressure with 19.Rd1 Kd8 20.Be4 Kc8 21.Nd5 as it is not easy for Black to involve his kingside in the game. 16.Bb5+ Kd8 17.Ba4 Kc7 18.Rhe1² Black has solved his structural problems, but it is not easy for him to complete development. 18...Qf5?! After both 18...h5 19.Ne4 Qb4 20.Bb3 Bxb3 21.axb3 and 18...Kb8 19.Bb3 Bxb3 20.axb3 White keeps the pressure on the centre. 19.Nb5+ Kb8 20.Nd4 Qa5 21.Bb3 Bxb3 22.axb3 h5 23.f5± With the e7-pawn fixed in place, Black can only wait passively while White manoeuvres. 23...Qc7 24.Re2 Re8 25.Nb5 Qd7 26.Nc3 Rc8 27.Qg5 h4 28.Qg4 Rh6 29.h3 e6 30.Rf1 e5 31.Rd1 Qe8 32.Re4 Be7 33.Qe2 Qf8 34.Ra4 Bd8 35.Rc4 Bc7 36.Nd5 Bb6 37.Rxc8+ Qxc8 38.Qg4 Qf8 39.f6 Rg6 40.Qd7 Rxg2 41.Rd3 Bd4 42.c3 Bc5 43.b4 Rg1+ 44.Kc2 e4 45.Rd2 1-0 13.6 Martin Jarabinsky 2164 Sergio Cardoso Garcia 2021 LSS email 2013 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 Bd7 7.Qd2 Rc8 8.0-0-0 Nxd4 9.Qxd4 Qa5 10.f4 Rxc3 11.bxc3 e5 12.Qb4 Qxb4 13.cxb4 Nxe4 14.Bh4 g5 15.fxg5 Be7 16.Bc4 h6 17.Rhf1 Be6 18.Bxe6 fxe6 19.c4 hxg5 20.Bg3 b6 21.Kc2 Nxg3 22.hxg3± Rh2 23.Rf2 a6 23...g4 24.Re1 24.Rd3! It’s crucial to activate the rooks before ...Kc8-d7-c6 and ...d6-d5 can be played. 24...Kd7 25.Ra3 a5 26.c5!? 26.bxa5 is winning but it permits counterplay: 26...d5 27.Ra4 Bc5 28.Rf7+ Kc8 29.cxd5 Rxg2+ 30.Kb3 exd5 31.Rg4+– 26...d5 27.cxb6 Bxb4 28.Raf3 Kc6 29.Rf6 Kxb6 30.Rxe6+ Kc5 31.Rxe5+– Settled positions are almost always lost for the side with the bishop vs. rook. Black threw in the towel on move 47. 13.7 Stefan Mazur 2413 Milan Bednar 2240 Slovakia tt 2013/14 (6) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nf6 3.Nc3 d6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Qc7 9.Kb1 h6 10.Bxf6 gxf6 11.f4 Bd7 12.f5!± Be7 A) 12...Nxd4 13.Qxd4 Be7 14.Be2, intending Bh5, but 14...h5 15.Qe3 0-0-0 16.Qh3 is also pretty unpleasant; B) 12...0-0-0 13.Bc4 Nxd4 14.Qxd4 Be7 15.Bb3 Kb8 16.Ne2± and eventually Nf4 will prompt the ...e6-e5 concession. 13.g3 The Bh3 plan is thematic, but I like 13.Nxc6 Qxc6 14.Be2 0-0-0 15.Bf3 Kb8 16.Ne2± and Nf4, when Black can’t really move. 13...b5? Now Black’s king will always be exposed. 13...Nxd4 14.Qxd4 Qc5 was better. 14.Bh3 14.fxe6! fxe6 15.Nce2 Nxd4 16.Nxd4± 14...Nxd4 15.Qxd4 0-0?! 16.fxe6 fxe6 17.Qd2 Kh7 18.Ne2 f5 19.exf5 Once Black’s pawns are disjoined, it’s easy for White to invade. 19...e5 19...exf5 20.Nf4 20.Nc3 Bc6 21.Rhf1 21.Bg2! 21...Qb7 22.f6 Bxf6 23.Qxd6 Rad8 24.Bf5+ Kg7 25.Qb4 Bf3 26.Be4 Rxd1+ 27.Rxd1 Be7 28.Bxf3 Rxf3 29.Qg4+ Kf8 30.Nd5 Rf7 31.Qg6 Bg5 32.Qd6+ 1-0 13.8 Darmen Sadvakasov 2615 Rinat Jumabayev 2421 Astana ch-KAZ 2007 (3) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 Qb6 8.Nb3 a6 9.0-0-0 Qc7 10.Kb1 b5 11.f4 b4 12.Bxf6 gxf6 13.Ne2² Bd7 A) 13...Be7 14.f5 e5 15.Ng3ƒ is a great structure for White; B) 13...Rb8 14.Nbd4 Nxd4 15.Nxd4 Bb7 16.Bd3±; C) 13...Qb6 14.f5 a5 15.Nbd4 Bd7 16.Nxc6 Qxc6 17.Ng3± 14.Ned4 14.f5!? 14...Qb6 14...Nxd4 15.Nxd4 15.Be2 15.Bc4!? 15...Nxd4 16.Nxd4 The rest of the game is a bit uneven, but shows how the position can flare up in a practical game. 16...h5 This is a bit optimistic, ignoring development; 16...a5². 17.Rhe1 17.e5!? is best timed here, before Black has developed: 17...dxe5 18.fxe5 fxe5 19.Nf3 Ba4 20.Nxe5 Qc7 21.Nc4± 17...Rc8 18.Bf3 18.Nf3!± is a superior way to support e4-e5. 18...Bh6 This feels like a bluff. 19.g3? 19.Bxh5 e5 20.Ne2± 19...h4 20.Qd3 a5 21.e5 fxe5 22.fxe5 22...d5? This loses to a stock Sicilian sacrifice. 22...Bg7! 23.exd6 Qxd4 24.Qxd4 Bxd4 25.Rxd4 hxg3 26.hxg3 Rh2 gives Black plenty of dynamics for the pawn. 23.Bxd5! exd5 24.e6+– White’s attacking advantage is too great. 24...fxe6 25.Qg6+ Ke7 26.Nf5+ Kd8 27.Rxd5 Qc6 28.Qf6+ Kc7 29.Qe5+ Kb7 30.Nd6+ Ka6 31.Rxa5+ Kb6 32.Qd4+ Kc7 33.Nxc8 Be3 34.Qe5+ Kxc8 35.Qxh8+ 1-0 13.9 Torbjorn Ringdal Hansen 2442 Jens Hirneise 2315 Hofheim 2017 (3) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Nc3 d6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 Nf6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 Be7 8.0-0-0 0-0 9.f4 d5 10.e5 Nd7 11.h4² 11...Nxd4 11...Nb6 12.Nf3 Bd7 13.Kb1 h6 14.Bxe7 Qxe7 15.g4± 12.Qxd4 12.Bxe7!? Qxe7 13.Qxd4 makes sense as 13...Qc5 would be a slower way to trade queens. 12...Bc5 12...f6 13.exf6 Nxf6 14.g3² 13.Bxd8 Bxd4 14.Rxd4 Rxd8 15.g3² 15.g4! 15...b6 16.Bg2 16.Nb5!? Nc5 17.Nd6 Nb7 18.Nxb7 Bxb7² should be defensible, but not without some suffering. 16...Bb7 17.Rhd1 Nb8 18.Nb5 Nc6 19.R4d2 The problem for Black is that even when White doesn’t play perfectly, the maximum he can hope for is a draw. 19...Na5?! 19...Ne7 was better. 20.b3± Bc6 21.Nd4 Rac8 22.Kb2 b5 23.a3?! 23.Bf1! a6 24.a4± 23...a6 24.Re1 White starts to play a bit too indirectly. 24.f5! 24...Bd7 25.Re3?! 25.f5! 25...Nc6 26.Rc3 Nxd4 27.Rxc8 Rxc8 28.Rxd4 Kf8 29.c4 bxc4 30.bxc4 Rxc4? 30...Ba4!= prepares 31...Rc2+ and should be a draw. 31.Rxc4 dxc4 32.Kc3 Bb5 33.Be4 h5 34.Bc2 Ke7 35.a4 Bc6 36.Kxc4... 1-0 (49) 13.10 Davit Shengelia 2582 Georg Danner 2418 Oberwart 2010 (3) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 d6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 Be7 8.0-0-0 Nxd4 9.Qxd4 0-0 10.f4 h6 11.h4 hxg5 12.hxg5 Ng4 13.Be2 e5 14.Qg1 exf4 15.Bxg4 Bxg5 16.Bxc8 Rxc8 17.Kb1² Re8 17...Rc5!? avoids the loss of the a7-pawn, but 18.g3 f3 19.Qf2!N 19...Qf6 20.Nd5 Qg6 21.Qxf3 preserves all White’s attacking chances. 18.Rd3!? In a practical game, it’s tempting to pursue the attack, but cleanest was 18.Qxa7! Re6 19.Rd3 Qc7 20.Qg1 Qc5 21.Qd1 Bh6 22.g3 fxg3 23.Rxg3± as in Kraft-Peters, email 2010. 18...Rc5 19.g3 f3 20.Rxf3 Qe7 20...Re6!? might be best, to meet 21.Qh2 with 21...Rh6. 21.a3 21.Qh2 Bh6 22.a3± 21...Qe6 22.g4 Qg6?! 22...f6 deserved attention, to evacuate the king. 23.Rf5 23.b4! is the concrete approach, overloading the c5-rook: 23...Rc4 (23...Rce5 24.Qxa7+–) 24.Rfh3 Bh6 25.g5+– 23...b6 24.Rh5 Bh6 25.Qg3 Rxc3? 25...f6± 26.Qxc3+– Rxe4 27.Qc8+ Kh7 28.Rxh6+! gxh6 29.Qf8 Re1+ 30.Ka2 f6 31.Rxf6 Qg8+ 32.Rf7+ 1-0 13.11 Sergei Movsesian 2700 Hou Yifan 2575 Khanty-Mansiysk 2011 (1) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Be7 9.Bxf6 gxf6 10.f4 Bd7 11.Kb1 b5 12.Nxc6 Bxc6 13.Bd3± b4 White’s plan for light-square domination is demonstrated in the line 13...Qb6 14.f5 0-0-0 15.Rhe1 Rde8 16.Ne2 Kb8 17.Nf4 e5 18.Nd5 Bxd5 19.exd5± when Re4/a2-a4 will be dangerous. 14.Ne2 Qb6 15.f5! e5 16.Ng3 h5 Other moves make it easy for White to construct his ideal set-up, e.g. 16...d5 17.exd5 Bxd5 18.Be4 Bxe4 19.Nxe4± or 16...a5 17.Bc4 a4 18.Qe2±. 17.Qe2 17.h4!? would mark the h5-pawn for death. 17...h4 18.Nh5 This is fine but more demanding, whereas after 18.Nf1 a5 19.Bc4 Qc5 20.Qd3 a4 21.Ne3 the position plays itself due to White’s firm central grip. 18...Qc5 18...Kd8!? 19.Bc4 Bb5 20.g4 hxg3 21.hxg3ƒ 19.g4 hxg3 20.hxg3 Kd7 21.g4 Kc7 22.Rh3? 22.Rc1! and c2-c3 is necessary before Black breaks out with ...d6-d5; if 22...Rab8 23.Bc4±. 22...Rhg8? 22...d5! 23.exd5 Qxd5 24.Bxa6 Qg2 25.Rg3 Qxe2 26.Bxe2 Rag8° 23.Ng3 Rh8 24.Nh5 24.Rxh8 Rxh8 25.Bxa6± 24...Rhg8 25.Rdh1 25.Rc1! 25...a5 26.Bc4 a4? Black could destabilise White’s light-squared hold with 26...Rxg4! 27.Qxg4 Qxc4 28.Ng3 a4=. 27.Bxf7 a3 28.Rd1? 28.Bxg8 Rxg8 29.bxa3 bxa3 30.Rb3 Ba4 31.Rc1!+– and cxb3 is the trick perhaps missed by both players. 28...axb2 28...Rg5 29.Bxg8 Rxg8 30.Rb3 30.Kxb2 Bb5 31.Qe3 Qxe3 32.Rxe3+– Rxg4 would give Black fighting chances were it not for 33.Rg3! Rxe4 34.Rg7 with crushing threats. 30...Bb5 31.Qf3 Bc4 32.Rxb2 Qa5 33.Ng3 Ra8 34.Kc1 34.Nf1 34...Qc5 35.Nf1 Ra3 36.Qg2 Bxa2 37.Nd2 Bg8 37...d5! 38.Qg1 Ra1+ 39.Nb1 d5! 40.exd5 Qxg1 41.Rxg1 Bxd5 It’s not so unusual for the bishop pair to match the rook and knight, but Black later went astray in the second time control. (1-0, 61) 13.12 Ejvind Jensen 2468 Adam Zmokly 2506 ICCF email 2010 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f4 b5 10.Bxf6 gxf6 11.Kb1 Nxd4 12.Qxd4 Be7 13.f5 Qc7 14.Qd2 Qc5 15.Ne2! Bc6 15...a5 16.Nf4 b4 17.g3!? (setting up Bh3 against quiet moves) 17...Rc8 18.Ba6 Rc7 19.Rhe1 a4 20.b3 a3 21.Bc4 Qe5 22.Nd3 Qd4 23.Qe3± Daskal-Meissner, email 2010. 16.Nf4 16.Nd4! Bd7 17.fxe6 fxe6 18.g3± 16...e5 17.Nd5 Bxd5 18.Qxd5± Rc8 18...Qxd5 19.Rxd5 (these endgames are thankless for Black due to his passive e7-bishop) 19...h5 20.c4 b4 21.Be2 h4 22.Kc2± 19.c3 Qb6 20.Be2 Rc5 21.Qd2 0-0 22.Qh6! Qb7 23.g4 Qxe4+ 24.Bd3 Qf4 25.g5 Kh8 26.Qh3 e4 27.Rhf1 Qxg5 28.Bxe4 Rg8 29.Bd5 As Botvinnik once put it, a position can often be correctly assessed by comparing the bishops! 29...a5 29...Rg7 30.Qd3 Bf8 31.Rde1 30.Bxf7 Rg7 31.Bd5+– b4 32.c4 And 1-0 (55). 13.13 Gerd Branding 2607 Hector Walsh 2649 ICCF email 2005 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 h6 9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.Bf4 d5 11.Qe3 Qa5 12.Be2 dxe4 13.Nxe4 Nd5 14.Qg3 Qxa2 15.Be5!± Bb7 15...Rg8 16.c4 Qa1+ 17.Kc2 Qa4+ 18.b3 Qa2+ 19.Bb2 Ba3 20.Rb1 Nb4+ 21.Kc3 Bxb2+ 22.Rxb2 Qa5 23.Rbb1 Nd5+ 24.Kb2 kept White’s king safe before turning the screws on Black’s position, Branding-Peli, ICCF 2000. 16.Bh5! Qa1+ 16...Rg8 17.Qf3 g6 18.Rxd5 Be7 loses tactically to 19.Rd3!N 19...Qa1+ 20.Kd2 Qxh1 (20...Qa5+ 21.Bc3 Qxh5 22.g4 Qb5 23.Nf6+ Kf8 24.Rd7+–) 21.Bf6! and Black can’t defend himself on the dark squares. 17.Kd2 Qa5+ 18.Ke2 Qb5+ 19.Rd3 Qa4 20.Qf3! Qxc2+ 21.Rd2 Qc4+ 22.Kd1 Contrary to appearance, White’s king is safer than Black’s because of the difference in piece activity. 22...g6 22...0-0-0 23.Bxf7 Nb4 24.b3 Rxd2+ 25.Nxd2 Qc2+ 26.Ke2 Kd7 27.Rd1 left Black unable to develop the kingside in Mignon-Adriano, email 2010. 23.Bxg6! fxg6 24.Bxh8 0-0-0 25.b3 25.Be5!? 25...Qb5 26.Be5 a5 27.Kc2 Bb4 28.Qh3 Ba6 29.Nc3 Bxc3 30.Bxc3± White has a solid material advantage and can play around Black’s pieces with the opposite-coloured bishops. 30...a4 31.Qxe6+ Kb7 32.Rb1 a3 33.Qe4 a2 34.Rbd1 Qc5 35.Qd4 Qa3 36.Bb2 Qd6 37.Kc1 Re8 38.Ba1 Qa3+ 39.Qb2 Qc5+ 40.Rc2 Qb4 41.Qxa2 Qf4+ 42.Rcd2 Nb4 43.Qa4 Bb5 44.g3 Nd3+ 45.Kb1 Qxd2 46.Qxb5+ cxb5 47.Rxd2 Re1+ 48.Kc2 Nxf2 49.Rxf2 Rxa1 50.Kc3 Rh1 51.Kb4 h5 52.Kxb5 g5 53.Kc5 h4 54.Kd5 Kc7 55.Ke5 Rg1 56.Rf3 1-0 13.14 Björn Fagerström 2480 Raivo Dzenis 2466 ICCF email 2009 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Nc3 d6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 Nf6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 h6 9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.Bf4 d5 11.Qe3 Be7 12.Be2 0-0 13.h4 Re8 14.g4 Nd7 15.Qg3 e5 16.Bd2+– Nc5 16...d4 17.Na4 has scored 6/6 in correspondence games! 17...g6 (17...Nf6 18.Qg2! Nh7 19.g5 g6 20.Rdg1 Be6 21.h5! was killing in Scheider-Malcher, Germany 2014; 17...Nc5 18.Nxc5 Bxc5 19.g5 h5 20.g6 Be6 21.Qxe5 Qd6 22.Qxh5 fxg6 23.Qxg6 was likewise a decisive white initiative in Robson-Lyukmanov, email 2009) 18.Bc4!? (18.Bxh6 is also fine, of course) 18...Bf8 19.f4 exf4 20.Bxf4 Nf6 21.e5 Nd5 22.Rxd4 White was a pawn up with the initiative in JacotGallinnis, email 2008. 17.g5 d4 17...h5 18.exd5 Rb8 is a desperate attempt refuted by 19.g6!. 18.gxh6 Bf6 19.hxg7! dxc3 20.Bxc3 Qe7 21.Qe3! Kh7 22.Bd2 Forcing Black to take on g7 is the key to opening the floodgates to his king. 22...Bxg7 23.Rhg1+– Qf8 24.Rxg7+! Qxg7 25.Qxc5 Black could already resign as his king is too open. 25...Rg8 26.f4 Bh3 27.Bc3 Qh6 28.Qxe5 Rae8 29.Qc7 Qe6 30.Rd6 Re7 31.Qxc6 Rd7 32.Qxd7 Qxd7 33.Rxd7 Bxd7 34.Bxa6 Rg4 35.Be5 Bc6 36.Bd3 Rxh4 37.b4 Rh3 38.b5 Rxd3 39.cxd3 Bxb5 40.Kd2 Kg8 41.d4 Kf8 42.d5 Ke7 43.Ke3 Kd7 44.Bc3 Ke7 45.Kd4 1-0 13.15 Emanuel Miciak 2387 Stefan Belak 2293 ICCF email 2010 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 h6 9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.Bf4 d5 11.Qe3 Qa5 12.Be2 Bb4 13.Be5 Be7 14.exd5 cxd5 15.h4 Bb7 16.Rh3 Qc5 17.Qf4 Rc8 18.Rg3 White’s attack is straightforward – Black can’t really untangle to use his central majority. 18...Kf8 18...Rg8 19.Kb1 Ne4 (19...Kf8 20.Rf3!±) 20.Rxg7 Rxg7 21.Bxg7 Qxf2 22.Qxf2 Nxf2 23.Rf1 Bxh4 24.Bh5 a5 25.Nb5 Ba6 26.a4±; White will quickly regain the pawn with Bd4. 19.Kb1 Ne8 20.a3! I like this move, slowly improving the position. 20.Rf3 Bf6 21.g4 Qe7² 20...Bf6 21.Rd4 Bxe5 22.Qxe5 Qc7 23.f4± White doesn’t put a foot wrong in this game, tying up Black’s pieces and structure. 23...Nf6 24.Rb4 Rg8 25.Qd4 a5 26.Rb3 Nd7 27.Na4! Qxc2+ 28.Ka2 Bc6 29.Nb6 Ke7 30.Nxc8+ Rxc8 31.Ba6 Rc7 32.Rbc3 Qe4 33.Qxe4... 1-0 (61) 13.16 Valery Ivanov 2258 Giorgio Perez 1773 LSS email 2012 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Nc3 d6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 Nf6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 h6 9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.Bf4 d5 11.Qe3 Qa5 12.Be2 Bb4 13.Be5 Bxc3 14.Bxc3 Qxa2 15.Bd3 dxe4 16.Qg3 exd3 17.Qxg7 Rg8 18.Qxf6+– 18...d2+ 18...Qa1+ 19.Kd2 Qa4 20.Ke3! Ra7 21.Rxd3 Rd7 22.Rhd1 Rd5 23.g3 Qxc2 24.Bb4 c5 25.Rxd5 (25.Bc3! Qxd1 26.Rxd1 Rxd1 27.Bd2+–) 25...exd5 26.Rxd5 Qb3+ 27.Rd3 Qe6+ 28.Qxe6+ Bxe6 29.Bxc5± and Black couldn’t hold the endgame in Priebe-Buchholz, email 2005. 19.Kxd2 Qd5+ 20.Ke3 20.Kc1 Qg5+ 20...Qg5+ 21.Qxg5 Rxg5 22.Bf6 Rd5 23.c4 The penetration of the king on the dark squares is inevitable. 23...Rd7 23...Rxd1 24.Rxd1 Bd7 25.Kd4+– 24.Rd4! Rxd4 25.Kxd4 Ra7 26.Kc5 a5 27.Kb6 Rb7+ 28.Kxc6 Rd7 29.f3 Ba6 30.c5 Bb7+ 31.Kb6 Bd5 32.c6 Rd6 33.Rc1 e5 34.Rc5 Rxf6 35.Rxd5 1-0 13.17 Mark Noble 2560 Evgeny Gaysin 2430 ICCF email 2012 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 h6 9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.Bf4 d5 11.Qe3 Bb4 12.Be2 0-0 13.e5 Nd7 14.Qg3 Kh8 15.Qh3 Bxc3 16.Qxc3 Qb6 17.Qh3 Qxf2 18.Bf3 Nxe5 19.Rd2 Qc5 20.Bxe5 f6 21.Bg3 e5 22.Qh5 Rb8 23.Rd3 Be6 24.Rc3± Qb4 25.Rb3 Qa4 26.Kb1 c5 Black’s centre looks imposing, but White can return the piece for the initiative. 27.Bxe5! fxe5 28.Qxe5 Rxb3 28...Rbe8 29.Rb7 Bf7 30.Qd6 d4 31.b3 Qa5 32.Rd1 Rd8 33.Qb6 Qxb6 34.Rxb6+– picked up queenside pawns in Martin Clemente-Vosahlik, email 2007. 29.axb3 Qd7 30.Re1 Rf6 31.Rd1 Bg8 32.c4 Qb7 32...Rb6 33.Bxd5 Rxb3 34.Kc1 Qc8 35.Bxg8 Kxg8 36.Rd6± would require detailed analysis to prove a hypertheoretical assessment, but Black’s king will always be weak. 33.Qc3 Qb8 34.cxd5 Rb6 35.Ka2 Rb4 36.Re1 Qd8 37.Qxc5 Rb5 38.Qc3 Bxd5 39.Bxd5 1-0 The game ending here is surprising, as Black’s position is hardly resignable: 39...Ra5+ 40.Kb1 Qxd5 41.Qc4± 13.18 Vladimir Gerasimov 2476 Joze Novak 2527 ICCF email 2013 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 h6 9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.Bf4 d5 11.Qe3 Bb4 12.Be2 0-0 13.e5 Nh7 14.a3 Be7 15.h4 15...Qa5 A) 15...Bd7 16.Rh3 f6 17.Na4! fxe5 18.Bxe5±; B) 15...f5 16.exf6 Nxf6 17.g4 with attack, Clement-Nichols, email 2010; C) 15...a5? 16.g4! Ba6 17.g5 Bxe2 18.Qxe2±; D) 15...c5 16.Bxh6! gxh6 17.Qxh6 gives White a sustained attack: 17...Ra7 (17...f5 18.g4 Kh8 19.Rdg1 Rf7 20.gxf5 Qf8 21.Qg6 Rxf5 22.Bd3 Rf7 23.Rg4 Bd7 24.Rf4 Be8 25.Nxd5!±) 18.Bd3 f5 19.g4 c4 20.gxf5 Kh8 21.Rhg1 Rf7 22.fxe6 Bf8 23.Qh5 Bxe6 24.Bxc4 Rxf2 25.Bxd5 Bxd5 26.Nxd5 Qc8 27.Qg6± White has four pawns for the piece, plus Black’s king is bare; E) Best is 15...Qc7 16.Bd3 Kh8 (16...Rb8 17.Rh3 Kh8 18.Rg3 h5 19.Bxh7 Kxh7 20.Bg5ƒ) 17.Ne4 Qa7 18.Qxa7 Rxa7 19.Nd6 Bxd6 20.exd6 Nf6 21.Be3 Rd7 22.c4. The d6-pawn continues to annoy. 16.Rh3 Kh8 16...Bc5 17.Qg3 Kh8 18.Qh2! Rb8 19.Na2 Bd7 20.g4± 17.g4 Rb8 18.Nb1 c5 19.g5 White’s attack is considerably faster. 19...Bd7 19...h5!? 20.Bxh5 Bd7 21.g6 fxg6 22.Bxg6 and White attacks. 20.gxh6 g6 21.Rg1 Qb6 22.b3± Rg8 23.c4 a5 24.Nd2 d4 25.Qd3 a4 26.Bd1 Qa7 27.bxa4 Bxa4 28.Bxa4 Qxa4 29.Rgg3 Rb6 30.Qc2 Qa7 31.Rb3 Rgb8 32.Rxb6 Rxb6 33.Kd1 Qb7 34.Rb3 Qh1+ 35.Ke2 Rxb3 36.Qxb3 Qxh4 37.Qf3 Ng5 38.Bxg5 Bxg5 39.Ne4 Bd8 40.Nd6 Kh7 41.Nxf7 Bc7 42.a4 Qh5 43.Qxh5 gxh5 44.Ng5+ Kxh6 45.Nxe6 Bxe5 46.a5 Bb8 47.Nxc5 1-0 Chapter 14 The Richter-Rauzer 8...Bd7 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f3!? I can’t promise an advantage for White in all lines, but that’s also the current verdict on the main line 9.f4. The main challenge for both sides in this English Attack set-up is navigating all the move orders. To assist with this, the material is divided into sections based on Black’s development. 9.Nxc6 Bxc6 10.f3 is the radical way to avoid the annoying ...Nxd4 lines, but every move order comes at a price. 9...Be7 It’s hard for Black to omit this move forever, but he often delays it to try and outsmart White. Rare move orders A) 9...Nxd4 10.Qxd4 Be7 will transpose back to 9...Be7 after either 11.Kb1 (or 11.h4; 11.g4 h5 12.gxh5 Nxh5 13.Bxe7 Qxe7 14.Rg1 Bc6 is fine for Black, as 15.Qxd6 Qxd6 16.Rxd6 Nf4 offers plenty of positional compensation for the pawn); B) 9...Qa5 as usual wastes time: 10.Nb3 Qc7 11.f4! Be7 12.Be2, and Black ends up in a bad version of 9.f4: 12...b5 (12...0-0-0 13.Bh4!? Kb8 14.Bf2 is a compelling manoeuvre to exploit the opened queenside: 14...Bc8 15.Kb1 d5 (what else can Black do?) 16.e5 Nd7 17.Rhe1 g5 18.g3±) 13.a3 Rb8 (13...b4 14.axb4 Nxb4 is too early because of the strike 15.e5! dxe5 16.fxe5 Nfd5 17.Bxe7 Kxe7 18.Kb1±) 14.Rhf1N 14...b4 15.axb4 Rxb4 16.Bxf6 gxf6 17.Rf3 Qb6 18.Qd3 and Black’s queenside play hasn’t achieved very much; C) 9...Qc7 10.Kb1 Nxd4 (10...Be7 transposes to 9...Be7) 11.Qxd4 Be7 is an inaccurate move order in light of 12.Be3! 0-0 13.g4 b5 14.g5 Ne8 15.h4 with the much faster flank attack; D) 9...Rc8 10.Kb1 b5 (10...h6 11.Be3 transposes to 9...h6; 10...Be7 transposes to 9...Be7) 11.a3!? (my rule of thumb is to play a2-a3 when Black has played ...Rc8, as then he often requires ...Rb8 to prepare ...b5-b4) 11...Be7 12.Be3 h5!? This is a necessary evil, else g4-g5 is too fast. 13.Rg1! Ne5 14.h3 h4 15.f4 Nc4 16.Bxc4 bxc4 17.Nf3² and White had the superior structure in Krabbe-Adam, email 2009; E) 9...b5 10.Kb1 is very likely to transpose to one of the other lines. 10...Qb6?! (this is often seen in the 9.f4 variation, but here it loses time. 10...Be7 leads to 9...Be7; for 10...Rc8 see 9...Rc8; 10...h6 11.Be3 reverts to 9...h6 territory) 11.Be3 Qb7 12.g4 h6 13.h4 Ne5 14.Qg2!ƒ White’s kingside attack is faster because g4-g5 hits the h6 hook, Short-Leon Nanjari, Linares 2000. The kingside hook 9...h6 10.Be3 A) 10...Nxd4 11.Bxd4 b5 12.Kb1 b4 (12...Be7 13.g4ƒ and h2-h4/Bd3/g4-g5 plays itself) 13.Ne2 e5 14.Be3 is a bad structure for Black, Sanchez-Huerga Leache, San Juan 2008; B) 10...h5 is less effective before White has played h2-h4: 11.Kb1 Be7 12.a3!?N Black’s only source of counterplay is ...b5-b4, so this is hardly a waste of time. 12...Qc7 (12...b5 13.Be2 Nxd4 14.Bxd4² White is ready to play in the centre with f3-f4 and e4-e5) 13.Nxc6! Bxc6 14.Bf4 Rd8 15.Bd3 Now Black’s structure is fixed, and we can manoeuvre toward the e4-e5 break, as in the following line: 15...b5 16.Qe1!? 0-0 17.e5! Ne8 18.Qe3²; C) 10...Rc8 11.g4 b5 (11...Nxd4?! is ineffective when we can recapture 12.Bxd4!; 11...Ne5 12.h4 b5 13.a3 Qc7 14.Be2 Nc4 15.Bxc4 Qxc4 is an ineffective plan, and 16.Nb3 followed by g4-g5 gives a sustainable initiative) 12.h4 Qc7 (after 12...b4 13.Nce2 d5 14.Nxc6 Bxc6 White successfully ignores 15...dxe4 with threats of his own by 15.Nd4! Qa5 16.Kb1 dxe4 17.Nxc6 Rxc6 18.fxe4 Rd6 19.Qe2 Rxd1+ 20.Qxd1. White’s pointed play has been rewarded with the bishop pair advantage) 13.Kb1 Ne5 (13...b4 14.Nce2 d5 is far too ambitious because of the standard trick 15.Nxc6 Bxc6 16.Nd4 Bb7 17.e5!± and taking on e5 hangs the queen to Bf4) – see the 10...b5 main line; D) For 10...Be7 11.g4 b5 12.h4 see Matsuura-Mekhitarian, Sao Paulo 2007, where you’ll find the inclusion of ...h7-h6 accelerates White’s kingside attack; E) 10...Qc7 is inaccurate, as now ...b7-b5 can be met with the typical Bxb5 sacrifice: 11.Kb1 and now: E1) 11...b5? 12.Ndxb5! axb5 13.Nxb5 Qb8 14.Nxd6+ Qxd6 15.Qxd6 Bxd6 16.Rxd6 White is much better, but it is important to know how to handle this endgame – see Yanushevsky-Bajt, email 2013; E2) 11...Rb8 12.g4 Ne5 13.h4 b5 14.a3² – see 10...b5; E3) 11...Ne5?! 12.f4 Nc4 13.Bxc4 Qxc4 14.e5 Nd5 15.Nxd5 Qxd5 16.exd6 Qxd6 17.Qf2!± and next f4-f5 fully exploits Black’s lack of development; E4) 11...Na5?! (the most common move, but ...Nc4 doesn’t have much sting in general: 12.g4 b5 13.a3 Rb8 (13...Nc4 14.Bxc4 Qxc4 15.h4± is too fast) 14.h4 g6 In Bologan-Salem, Khanty-Mansiysk 2013, White had the opportunity to kill Black’s rim knight with 15.b3!? Rc8 16.Nde2, and Black is starved of counterplay. F) 10...b5 11.Kb1 Be7 (11...Rc8 12.a3 Ne5 13.g4 Qc7 14.Be2! Nc4 15.Bxc4 Qxc4 16.h4 and even with White spending a tempo on Be2, Black’s play is miles too slow; after 11...Ne5 12.a3 Rb8 13.g4 Qc7 14.h4 White has some edge in this opposite-flank attacking race, see Rosa Ramirez-Boccia, email 2011; for 11...Qc7 – see 10...Qc7) 12.g4 This position could arise from a few move orders, but I’ve covered it here to emphasise how inserting ...h7-h6 and Be3 has harmed Black’s overall game. F1) 12...Nxd4 13.Qxd4! (this is an exception to the rule of thumb, as I want to delay ...b5-b4) 13...Rb8 14.h4 b4 15.Ne2 e5 16.Qd2 Be6 17.Ng3 Qa5 18.b3± White’s kingside play was considerably faster in Klovans-Euler, Werfen 1996; F2) In the event of 12...Ne5 13.a3 Qc7 14.h4 Rb8 15.Be2 Nc4 16.Bxc4 bxc4 17.Ka1 Qb7 18.Rb1± Black’s queenside counterplay comes to an abrupt end, Sherwood-Ederer, email 2012. In general Black should avoid this structure; F3) 12...Qc7 13.a3 Nxd4 14.Bxd4!N (as usual, this is how we want to meet ...Nxd4 given the choice. 14.Qxd4 Bc6 15.h4 Rd8 might also favour White, but is less clear) 14...Qb7 15.h4 e5 (if Black doesn’t play ...e6-e5 he risks getting run over with g4-g5, but this is also weakening) 16.Be3 a5 17.b3! b4 18.Na4 Bxa4 19.bxa4 The open king looks like a problem, but White keeps control: 19...bxa3+ 20.Bb5+ Nd7 21.Ka2 Qc7 22.g5 and White keeps Black pressured. 9...Be7 – main line with 10.h4 9...Be7 It’s hard for Black to omit this move forever, though we saw he often delays it to try and outsmart White. 10.Nxc6!? Bxc6 11.Kb1 b5 12.h4 is an interesting move order to avoid the annoying ...Nxd4 option in the other lines, but Black might then finesse back with the rare 9...Nxd4!. 10.h4 In most instances the play will transpose to 10.Kb1, but there are some differences. A) 10...Nxd4 is the most annoying line, though fortunately it remains quite rare. 11.Qxd4 A1) 11...Bc6 is a bit too slow after 12.g4 h6 13.Be3 d5 (normal moves don’t suffice for Black: 13...Nd7 14.Kb1 0-0? 15.g5!±) 14.exd5N 14...Bxd5 15.Nxd5 Nxd5 16.Bd2² The ...d6-d5 break doesn’t equalise in the Open Sicilian when it entails giving up the bishop pair!; A2) 11...b5 12.g4 0-0 13.Kb1 (this seems best, transposing to the 10.Kb1 0-0 analyses. 13.Bxf6 Bxf6 14.Qxd6 is White’s extra option with the 10.h4 move order, but it’s harmless after 14...b4! 15.Qxd7 bxc3 16.Qxd8 cxb2+ 17.Kb1 Rfxd8 18.Rxd8+ Rxd8 19.Bxa6 Rd2 20.Bd3 Kf8 with a drawish endgame. B) 10...0-0 11.Kb1 transposes to 10.Kb1; C) 10...Qc7 11.Kb1 (via the 10.Kb1 Qc7 move order, I recommend Nxc6 to avoid a delayed ...Nxd4. 11.Nxc6 Bxc6 12.Kb1 might therefore also be best here): C1) For 11...b5 12.Nxc6 Bxc6 see the 10.Kb1 Qc7 main line; C2) 11...h6 12.Be3 h5 13.Nxc6 Bxc6 transposes to 10.h4 h6 (13...bxc6 is a passive structure after 14.Be2ƒ); C3) 11...Nxd4 12.Qxd4 b5 C31) 13.g4 is the obvious try, but after 13...0-0! (worse is 13...h5 14.gxh5 Rxh5 15.a3 Rb8 16.Be2 a5 17.b4! Rc8 18.Kb2² and Black’s counterplay was at an end in Shablinsky-Salvador Marques, email 2008) I haven’t found a way for White to transform his pawn storm into an advantage: 14.a3 (14.Bxf6 Bxf6 15.Qxd6 Qxd6 16.Rxd6 Rfd8 17.a3 Be5 18.Rd1 Bc6 gives Black standard compensation for the pawn, with the bishop pair and active pieces) 14...Rfb8!N (this is particularly annoying, as the threat of ...a6-a5 and ...b5-b4 effectively forces White’s hand. 14...Rac8?! 15.h5 h6 16.Be3 Nh7?! 17.Bf4!± would represent White’s dream) 15.Bxf6 Bxf6 16.Qxd6 Qxd6 17.Rxd6 Be8= Black has the usual compensation, and can activate his rooks with ...a6-a5/...b5-b4; C32) 13.Qd2 b4! (13...h6 14.Be3 Bc6 15.Ne2!? Bb7 16.Nd4 would bring us to my absolute main line with 10.Kb1) 14.Ne2 a5 Black’s play is quite comfortable here, for example 15.g4 h5! 16.Bxf6 gxf6= with a great version of the Rauzer structure. D) 10...Rc8 11.Kb1 – see 10.Kb1 (11.g4!? looks good for an edge too, but scores modestly for White); E) 10...b5 11.Kb1 is 10.Kb1 territory; F) 10...h6 This is the most common reply, but I am generally happy to see it. 11.Be3 h5 Without this move, g2-g4-g5 will hurt (11...b5 12.g4 Nxd4 13.Qxd4 e5 14.Qd2 b4 15.Nd5 Nxd5 16.exd5 a5 17.Kb1 Rb8 18.Bd3 a4 19.g5± is a case in point; 11...Qc7?! is also too slow after 12.g4!) 12.Nxc6 Bxc6 13.Kb1 Black’s position looks solid, but his long-term problem is that castling kingside leaves him vulnerable to g2-g4 or a Ne2-g3(f4) attack on the h5-pawn: F1) 13...b5 14.Ne2 Bb7 15.Nd4 Rc8 16.g3! (sometimes the bishop is better on h3 than d3 when Black has his pawn on h5) 16...Nd7 17.Bh3 Ne5 (Steinke-Pascual Perez, email 2012) and now a slight improvement is 18.Bg5!? Nc4 19.Qc1 with a modicum of pressure; F2) 13...Rc8 14.Bg5 b5 (14...0-0 feels a bit early with the pawn on h5, and 15.Bd3 Re8 16.Ne2 b5 17.c3 Bb7 18.Bc2 gave White the more flexible position in Chiricuta-Krüger, email 2010 – meanwhile, Black must constantly watch out for Nf4 and grabbing the h-pawn) 15.Ne2² is covered in Shabalov-Soumya, London 2016; F3) 13...Qc7 14.Bg5! You might remember the importance of this fixing move from the previous edition. F31) 14...b5 15.Bd3 0-0 (15...b4 16.Ne2 a5 17.Nd4 Bd7 18.c4! is a typical way to cross Black’s queenside intentions: 18...bxc3 19.Rc1 Qb6 20.Qxc3 Rb8 21.Be3² with some momentum) 16.Ne2 Rfc8 17.Nf4 d5 18.e5 Qxe5 19.Nxh5 Nxh5 20.Bxe7 White has the bishop pair and a pending kingside charge; F32) 14...Rc8 15.Bd3 b5 (15...0-0 16.Ne2 Rfe8 17.Nd4² is an ideal piece set-up for White, who can play for g2-g4) 16.Ne2 Bd7 17.Ng3! and Black has problems completing his development; F33) After 14...0-0-0 15.Ne2!± Black had trouble finding counterplay in So-Sasikiran, New Delhi 2011. 9...Be7 Introducing the flexible 10.Kb1 10.Kb1 I can recommend this move if you want to dodge 10.h4 h6 11.Be3 h5, but it’s really a matter of taste. A) 10...h6 11.Be3 b5 transposes to 9...h6; B) 10...Nxd4! 11.Qxd4 Bc6 (it is ineffective to opt for 11...Qa5 12.h4 Rc8 13.Qd2 h6 14.Be3 e5 15.g4 Be6 16.Bd3±) is the one line where I was unable to prove an advantage, though it remains extremely rare: 12.h4 h6!, forcing the bishop to commit: B1) I checked 13.Bd2 b5 14.Bd3 (14.g4 is well met by the thematic 14...d5!=) 14...0-0 but I was unable to make progress here: 15.g4 (15.Qf2 Qc7 16.g4 Nd7 White is unable to pursue his attack, as g4-g5 is blocked up with ...h6-h5 and manoeuvring with 17.Ne2 Nc5 18.Be3 b4 19.Nd4 a5 doesn’t alter the situation) 15...d5 16.g5 (16.Qg1 b4 17.g5 bxc3 18.Bxc3 is creative but ineffectual after 18...Nh5 19.gxh6 d4=) 16...dxe4 17.Qxd8 Bxd8 18.Nxe4 Nxe4 19.Bxe4 Bxe4 20.fxe4 h5 and the machine quickly realises the endgame is just equal; B) 13.Be3 d5!N 14.e5 (if 14.Bd3!? dxe4 15.Bxe4 Qxd4 16.Bxc6+ Qd7 17.Bxd7+ Nxd7 18.Ne4 0-0-0 the engine gives White the faintest edge, but it’s just an equal endgame) 14...Nd7 15.Qg4 g6! I don’t see how White can prosecute his play, e.g. 16.f4 h5 17.Qh3 Qc7 18.Be2 Rc8 and it’s not easy to find a desirable break. Castling into the attack 10...0-0 11.h4 A) 11...Qc7 12.Nxc6! Bxc6 13.Bd3 b5 14.Ne2 Rfd8 15.Nd4 Bb7 16.g4 is very good for White, see Krivtsov-Eremin, email 2009; B) 11...Rc8 12.g4 b5 13.Nce2!? (13.Be3² is the main move, and scores brilliantly for White, see Neelotpal-Kozul, Skopje 2016) 13...Qc7 14.Nxc6 Bxc6 15.Nd4 Bb7 16.Bh3 Rfd8 17.Rhe1 and White is perfectly mobilised for a Be3/g4-g5 attack; C) 11...Nxd4 12.Qxd4 b5 is less precise here because of 13.Qd2! Bc6 14.Ne2! Bb7 15.Nd4 Rc8 16.g4, which can arise from various move orders, not least with Nxc6. 16...Nd7 (16...Qc7 17.Bd3 transposes to Parushev-Petkov, email 2011, though 17.Bh3!? may be even more powerful) 17.Bxe7 Qxe7 18.Qe3² White has scored superlatively in practice, and we’ll see White milk his edge in Krzyzanowski-Wosch, email 2011; D) 11...b5 12.Nxc6 (12.g4 Nxd4! 13.Qxd4 Qc7! In this version with ...Nxd4, White is unable to prove any edge. The game Engineer-Cato the Younger, Freestyle 2007, showed that White risks being worse if he doesn’t bail out now with 14.Bxf6 Bxf6 15.Qxd6 Qxd6 16.Rxd6 Rfd8 17.a3 Be5 18.Rd1 Bc6 and Black has obvious compensation for the pawn) 12...Bxc6 13.g4 (this is the best move order to avoid the displacement of White’s queen with ...Nxd4) 13...Rc8 14.Qh2!N 14...Bb7 15.Ne2 Qc7 16.Nd4 Rfe8 17.Bh3 keeps Black tied up while White moves his g5-bishop and advances the kingside pawns; Queenside play A) 10...Rc8 11.h4 (11.Be3 also looks promising, but 11.h4 has the advantage that we can play this line with either 10.Kb1 or 10.h4) 11...b5 (11...h5?! is mistimed with the bishop on g5: 12.f4! b5 13.a3 Nxd4 14.Qxd4ƒ; 11...h6 12.Be3 h5 13.Nxc6 Bxc6 transposes to 10.h4 h6 11.Be3 h5) 12.g4 Ne5 (12...Nxd4 13.Qxd4 0-0 14.Be3 transposes to the 13...Nxd4 note in Neelotpal-Kozul; 12...h5 13.gxh5 Nxh5 does White’s work for him: 14.Rg1 Nxd4 15.Qxd4 Nf6 16.a3²; 12...0-0 13.Nxc6 Bxc6 transposes to 10...0-0) 13.a3! Almost a novelty, but Black’s queenside attempts become increasingly strained after this prophylaxis. 13...Qb6 (White’s attack is swifter in the instance of 13...Rb8 14.Be2 0-0 15.Be3) 14.Be3 Qb7 15.Be2 and 15...b4 is an unsound pawn sacrifice, but 15...Nc4 16.Bxc4 bxc4 17.Ka1± does not yield the desired result either; B) 10...b5 is perhaps the one move Black ‘knows’ he’ll play, but the timing gives White the extra Bf4! option in reply to ...h7-h6: 11.h4 B1) 11...Ne5 12.g4 Qc7 (12...h6 is well met by 13.Bf4!? b4 14.Nce2 Nc4 15.Qxb4 d5 16.Qb7! and the complications work in White’s favour: 16...dxe4 17.Nc3 Na5 18.Qc7 exf3 19.Nxf3 Qxc7 20.Bxc7 Nc6 21.Rg1 with the more active position) 13.Qg2!N This proves an ideal square for the queen, as in many positions f3-f4 and e4-e5 can discover an attack on the a8-rook. 13...b4 (13...Rc8 14.Bc1 Nc4 15.Bd3 made it difficult for Black to continue his attack in Pereverzev-Norchenko, email 2010, due to White’s harmonious pieces) 14.Nce2 a5 15.Ng3 0-0 16.Nh5!ƒ A deep but strong idea, weakening Black’s kingside structure; B2) 11...Rc8 is the 10...Rc8 line; B3) 11...h6 12.Nxc6 Bxc6 13.Bf4! Qb6 (if 13...d5, 14.Qf2 keeps the pressure long enough to transition to a good French structure with 14...b4 15.Ne2 Qc8 16.e5 Nd7 17.Nd4²) 14.Ne2 Rc8 (14...e5 15.Be3 Qc7 16.Nc3 is a better structure for White, with g4-g5 in mind) 15.Nd4 Bb7 16.Be3 Qc7 – see 10...Qc7. The queen’s Sicilian square 10...Qc7 11.Nxc6! Bxc6 White’s attack is clearly faster in the structure 11...bxc6?! 12.g4ƒ. 12.h4 b5 For 12...0-0 13.Bd3 b5 14.Ne2 Rac8 15.Nd4 Bb7 16.g4² see Parushev-Petkov, email 2011. 13.Ne2 Bb7 A) 13...d5? 14.e5!; B) 13...h6 14.Be3 Rc8 15.Nd4 will probably transpose, as 15...Nd7?! 16.Nxc6 Qxc6 17.g4 Ne5 18.Be2 gives White the bishop pair to accompany his attacking chances. 14.Nd4 h6 A) 14...0-0 15.g4² is treated in Müller Alves-Daurelle, email 2011; B) 14...Rc8 15.g4 h5 16.gxh5 Nxh5 17.Bh3 Bf6 18.Bxf6 Nxf6 19.Qg5 Rh7 was a different approach in Arenas Vanegas-Escobar Forero, Quibdo 2015, trying to match White on the kingside. But this allows the blow 20.Bxe6!N 20...fxe6 21.Nxe6 Qe7 22.Qg6+ Qf7 23.Qxf7+ Kxf7 24.Ng5+ Ke7 25.Nxh7 Nxh7 26.Rhg1 Rg8 27.Kc1 with a material advantage for White. 15.Be3 We’ve come to a key position, where White seems to have the better chances, but we should be flexible depending on Black’s next move. 15...Rc8 A) 15...Nd7 is the usual move, but I found a big novelty in 16.c4!N to unexpectedly seize the initiative on the queenside! 16...b4 (16...bxc4 17.Bxc4 Qxc4? 18.Rc1 Qa4 19.b3 Qa3 20.Nc2 traps the queen) 17.Be2 (or 17.g4) 17...Rb8 18.g4± and Black lacks the space for a satisfactory game; B) 15...h5 is a bit delayed and 16.Bg5! Rc8 17.g3N 17...Nd7 18.Bh3, threatening 19.Bxe6, is unpleasant. 16.g4 Nd7 17.Rh2! I like this way of preparing g4-g5, as after 17.Bd3 Ne5 the bishop feels a bit awkward on d3: 18.g5 h5 19.f4 Nc4= I was unable to significantly improve on two drawn correspondence games. 17...Ne5 17...d5 18.exd5 Bxd5 feels too early with the king uncastled, and 19.Nf5 exf5 20.Qxd5 fxg4 21.fxg4 0-0 22.Rhd2 Rfd8 23.g5 with the bishop pair edge looks good in reply. 18.Qe1N 18...h5!? 18...Nc4 19.Bxc4 bxc4 20.Bd2² is a great structure for White. 19.gxh5 Rxh5 20.Qg3 Kf8 21.Be2 Black’s position is solid for now, but the next waves of attack are impending: 21...Nc6 22.Nxc6 Qxc6 23.Bd3ƒ And Bg5 will provoke further weaknesses. Summary 2...d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f3: 9...Rc8 +0.40 9...h6 +0.35 9...b5 – transposes to other lines 9...Be7: 10.h4 – +0.15 10.Kb1 – +0.20 14.1 Joseph Sanchez 2507 Mikel Huerga Leache 2440 San Juan 2008 (3) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 d6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f3 h6 10.Be3 Nxd4 11.Bxd4 b5 12.Kb1 b4 13.Ne2 e5 14.Be3± Qa5 A) 14...a5 15.g4 Bc6 16.Ng3±; B) 14...Rb8 15.Nc1 a5 16.g4 Qc7 17.Nd3 Be7 18.h4 Be6 19.Be2ƒ sets up g4-g5 and f3-f4. 15.Nc1 Be6 16.Bd3 The f1-bishop often doesn’t need to be developed for some time in the English Attack. 16.Nb3! Qa4 17.g4 Be7 18.h4 Qc6 19.Bh3ƒ 16...d5? Black tries too hard to defend b4. 16...Be7 17.Nb3 Qc7 18.Qxb4 0-0° was better. 17.Nb3 Qc7 18.exd5 Bxd5 19.Qe2 19.Bf2! Be7 20.Bg3 0-0 21.Rhe1 Bd6 22.Bh4± 19...Be7 20.Rhe1 a5? Black can’t afford to leave his king in an open centre. 20...0-0² 21.Bb5+! Kf8 22.Ba4 Bc4 23.Qf2 Kg8?! Now Black loses material. 23...Rb8 24.f4+– 24.Bb6 Qb8 25.Bc5 25.Nxa5+– 25...Bxb3 26.axb3 Bxc5 27.Qxc5 Kh7 28.Qxe5 Qxe5 29.Rxe5 Rhd8 30.Rxd8 Rxd8 31.Kc1 31.c4 31...Rd5 32.Rxd5 Nxd5 33.Kd2 Kg6 34.c4 bxc3+ 35.bxc3+–... 1-0 (69) 14.2 Everaldo Matsuura 2502 Krikor Mekhitarian 2416 Sao Paulo 2007 (2) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f3 Be7 9...h6 10.Be3 Be7 11.g4 b5 12.h4 10.Be3!? This avoids the ...Nxd4 lines. 10...b5 10...h5! exploits White’s move order, as Black has gained a free ...Be7 compared to 9...h6 10.Be3 h5: 11.h3!? Qc7 12.Bd3 h4 13.Nxc6 Bxc6 14.Kb1 b5 15.Rhe1 still gives chances for an edge though. 11.g4 h6 12.h4ƒ Nxd4 12...b4 13.Nxc6 Bxc6 14.Ne2 d5 (or 14...Qa5 15.Kb1 e5 16.Ng3±) 15.Nd4 Bb7 16.e5 Nd7 17.f4 (White has a perfect version of the French) 17...Bc5 18.Kb1 Qb6 19.Rh3± 13.Qxd4! 13.Bxd4 b4 14.Ne2 e5 15.Bf2! Be6 (15...Qa5 16.Kb1 Be6 17.Nc1²) 16.Qxb4 d5 17.Bc5 Bxc5 18.Qxc5 Rc8 19.Qa3² 13...Rb8 13...e5 14.Qd2 b4 15.Nd5! Nxd5 16.exd5 a5 17.Kb1 Rb8 18.Bd3 a4 19.g5± Odeeva-Oppermann, email 2011. 14.Bh3 b4 15.Ne2 e5 These measures are necessary to delay g4-g5. 16.Qd2 Qa5 17.Kb1± Be6 18.Nc1 Nd7 19.g5 19.Qg2!? is a natural way to prepare g4-g5. 19...h5?! 19...Bxh3 20.Rxh3 hxg5 21.Bxg5± 20.g6! The opening of the kingside is already close to decisive due to Black’s pawn weaknesses. 20...Nf6 21.Rdg1 Rg8 22.Rg5 Qc7 23.Qg2 Kf8 24.Rg1+– Bxh3 25.Qxh3 Rc8 26.Qg2 fxg6 27.Rxg6 Ne8 28.Nd3 a5 29.f4 Bf6 30.fxe5 dxe5 31.Bc5+ Qxc5 32.Nxc5 Rxc5 33.Rd1 Ke7 34.Qf2 Rc7 35.Qb6... 1-0 (53) 14.3 Nikolay Yanushevsky 2323 Drazen Bajt 2221 ICCF email 2013 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 h6 9.Be3 Bd7 10.f3 Qc7 11.Kb1 b5 12.Ndxb5 axb5 13.Nxb5 Qb8 14.Nxd6+ Bxd6 15.Qxd6 Qxd6 16.Rxd6± 0-0 17.Be2! Rfb8 17...Rfc8 18.Rhd1 Be8 19.c3! e5 20.b3± 18.c3 18.Rhd1 18...Na5 19.Rb6 Rc8 20.Ra6! The exchange of rooks favours White. 20...Rxa6 21.Bxa6 Ra8 22.Be2 Rc8 23.Bf2 e5 24.Bg3 Nc6 25.Rd1 Be6 26.b4 The black knights are unable to find stable posts. 26...Nh5 27.Bf2 Rb8 27...Nf4 28.Bf1 Ra8 29.Rd2 f5 30.g3 Nh5 31.a4!+– 28.Bc5 Nf4 29.Bf1 Ng6 30.Rd6 Na5 31.a4+– The advancing connected passed pawns are irrepressible. 31...Nf8 32.Bf2 Nb7 33.Rb6 Nd7 34.Rb5 Nf6 35.Bg3 Bd7 36.Rb6 Bxa4 37.Ba6 Nd7 38.Rxb7 Rxb7 39.Bxb7 Bb5 40.Kc2 Bf1 41.Bc6 Nb8 42.Ba4 f6 43.f4 Bxg2 44.Kd3 Bf1+ 45.Ke3 1-0 14.4 Victor Ramirez 2411 Mattia Boccia 2465 ICCF email 2011 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f3 h6 10.Be3 b5 11.Kb1 Ne5 12.a3 Rb8 13.g4 Qc7 14.h4² This line is somewhat important as it can arise from several move orders. 14...Qb7 A) On 14...Be7 15.Be2! readies g4-g5 and f3-f4; B) 14...d5 15.Bf4! Bd6 16.Bh2 (the threat of f3-f4 and e4-e5 compels Black to release the tension) 16...Nc4 (16...b4?! 17.axb4 Rxb4 18.exd5 Qb6 19.b3) 17.Bxc4 bxc4 18.exd5 Qb6 19.Qc1 Nxd5 20.Nxd5 exd5 21.Bxd6 Qxd6 22.Rhe1+ Kf8 23.Qe3± This is a strategic fantasy for White. 15.Be2 A) 15.Rg1! This preparation for g4-g5 goes unmentioned in Kozul/Jankovic’s The Richter Rauzer Reborn: 15...Nc4 (15...Be7 16.Qc1±) 16.Bxc4 bxc4 17.Qc1ƒ (this structure is very safe for White’s king) 17...Be7 18.g5 hxg5 19.hxg5 Nh5 20.Rh1 Kf8 21.Nde2± gave White positional control on both flanks in Colin-Skulason, email 2010; B) 15.Qc1 b4 16.axb4 Qxb4 17.Na2 Qb7 18.Be2 a5 19.g5 Nh5 20.Rdg1ƒ also looks good for White. 15...Nc4 16.Bxc4 bxc4 17.Qc1 Ng8 17...Be7 18.g5 Ng8 19.Nde2± 18.Ka1 Ne7 19.f4 Nc6 20.Nxc6 Bxc6 21.Rd4 Bb5 21...Be7 22.Rxc4 d5 23.exd5 exd5 24.Rd4± 22.g5 Be7 23.Re1 h5 24.Nxb5!? It’s a bit radical to change the position, but it’s not so easy to break through after 24.f5 e5 25.Rd2 Bc6. 24...axb5 25.c3 0-0 26.f5 g6 27.Qc2 Kh7 28.Rd2 Qa6 29.Kb1 Qc6 30.Red1 Rfe8 31.Rf1 Rb7 32.Rdf2 White wins by switching between the kingside and the d6 weakness. 32...e5 33.Rd2 Kg8 34.Rd5 Rd7 35.Qf2 Bd8 36.Qd2 Be7 37.Bc5 Red8 38.Bb4 Qb7 39.Ka2 Kh7 40.Qe3 Bf8 41.fxg6+ fxg6 42.Rf6 1-0 14.5 Alexander Shabalov 2563 Swaminathan Soumya 2384 London 2016 (3) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f3 Be7 10.Kb1 Rc8 11.h4 h6 12.Be3 h5 13.Nxc6 Bxc6 14.Bg5 b5 15.Ne2² Bb7 A) 15...Qc7 16.Nd4 Bd7 17.Bd3 g6?! (even the preferable 17...Qb6 18.Be2 Qc7 19.c3 Qb7 20.Bd3 0-0 21.g4 b4 22.cxb4 hxg4 23.h5 gave White a very strong attack in the model game Dolgov-Wosch, email 2010) 18.c3! I like very much how White won in Almasi-Murariu, Dresden 2007, but this looks even stronger: 18...e5 19.Nc2±; B) 15...Qb6 16.Nd4 Bd7 17.Qe3 Qc5 18.Bd3 Rb8 19.c3 also gives White the more harmonious position. It’s not easy for Black to engineer counterplay, as 19...b4 is now answered with 20.c4. 16.Nd4 Nd7 After the more common 16...Qc7, 17.g3!?N 17...Nd7 18.Bh3 places the bishop superbly, threatening sacs on e6: 18...Nc5 19.a3 and it is very hard for Black to improve his position. 17.Bd3 17.Be2 is a better placement for the bishop, supporting g2-g4. White can continue improving his position with c2-c3, Qe3 and so forth. 17...Qb6 17...Ne5 should be met with 18.Be2N, keeping the pieces on when possessing the space advantage. 18.Ne2 18.Be2!? 18...Qc5 18...Bf8² is the engine’s advice, but that already suggests that Black has gone astray. 19.Rc1 19.c3 was better. 19...Bxg5? Black shouldn’t open the h-file for White like this. 19...Ne5= 20.hxg5 Ne5 21.f4 21.Nc3!? 21...Ng4 22.Nd4 g6 23.Rce1 Kd8?! After the correct 23...0-0= Black’s king is very safe now that the g4-knight locks down the kingside. 24.Nb3 Qb6 25.Rhf1 Kc7 26.Qb4 26.f5!ƒ 26...Rhd8 27.Rf3 Kb8 28.a4 d5! 29.axb5 dxe4 30.Bxe4 Qxb5? 30...Bxe4 31.Qxe4 axb5 was better. The problem with this move is that White is not forced to trade queens! 31.Qa3!+– Black has no defence to a rook lift along the third or fourth rank. 31...Bxe4 32.Rxe4 Ka7 33.Rb4 Rd1+ 34.Ka2 Qd5 I suspect the game score is incorrect, but the final moves in the database are: 35.Qa4? 35.c4! Rxc4 36.Rxc4 Qxc4 37.Rc3+– 35...Rxc2 1-0 14.6 Wesley So 2667 Krishnan Sasikiran 2676 New Delhi 2011 (1) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f3 Be7 10.Kb1 Qc7 11.h4 h6 12.Be3 h5 13.Nxc6 Bxc6 14.Bg5 0-0-0 15.Ne2!± 15.Qd4!?± 15...Kb8 15...d5?! 16.e5! Ng8 17.Nd4±; 15...b6? 16.Nd4 Bb7 17.Qe3 Kb8 18.Rd3!± 16.c4 b6 17.Rc1 17.Nc3 Rhe8 18.Be2 Bb7 19.Bf4± leaves Black without a real move. 17...Rhe8 18.Nd4 Bb7 19.Be2 Rc8?! 19...Nd7² exchanges pieces when behind in space. Note that 20.Bxe7?! Rxe7 21.Qg5?! f6 22.Qxh5? Ne5 traps White’s queen! 20.Rhd1 Bf8 21.b4 Nd7 22.a4 Ka8 23.Ka2 23.Nb3! and a4-a5 is the ideal plan for dismantling the black monarch’s shelter. 23...g6 24.Nb3 f5! 25.exf5 exf5 26.a5 26.Bf1 26...Ne5 27.axb6 Qxb6 28.Be3 Qc7 29.Bf1 29.b5!? 29...Rcd8? It was essential for Black to open the centre with 29...Qf7! 30.Na5 d5 31.cxd5 Rxc1 32.Rxc1 Qxd5+ 33.Kb1ƒ when at least White will not be mating Black’s king in a hurry. 30.Bg1 Kb8 31.b5+– Nd7 32.bxa6 Bxa6 33.c5! 33.Qb4+ 33...Bxf1 34.cxd6 Qb7 35.Na5 Qa6 36.Rb1+ Bb5 37.Rxb5+ Qxb5 38.Rb1 1-0 14.7 Aleksey Krivtsov Nikolay Eremin 2115 ICCF email 2009 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Bg5 Nc6 7.Qd2 e6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f3 Be7 10.Kb1 b5 11.Nxc6 Bxc6 12.h4 0-0 13.Ne2 Qc7 14.Nd4 Bb7 15.Bd3 Rfd8 16.g4± b4 For 16...Rac8 see next game. 17.Rhg1 Rab8 Now White’s attack is trivial to execute, but 17...Rac8 18.Qe2 a5 19.Nb5 Qb8 20.f4± and Bxf6/g4-g5 is also frightening for Black. 18.Qh2 Qc5 19.Be3 Rdc8 20.h5+– Qe5 21.Qh3 Nd5!? 22.exd5 Qxe3 23.dxe6 fxe6 24.Rge1 Qf4 25.Nxe6 Qxf3 26.Qh2 Black has too many weaknesses and the tactics favour White. 26...Qg2 27.Qxg2 Bxg2 28.Nf4 Bh4 29.Nxg2 Bxe1 30.Nxe1 a5 31.Ng2 a4 32.Nf4 Kh8 33.b3 axb3 34.axb3 Rd8 35.Bc4 1-0 14.8 Das Neelotpal 2457 Zdenko Kozul 2609 Skopje 2016 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f3 Be7 10.Kb1 0-0 11.h4 b5 12.g4 Rc8 13.Be3² Ne5 13...Nxd4 14.Qxd4 Bc6?! (14...e5 15.Qb6 Qxb6 16.Bxb6 b4 17.Ne2 Rc6 18.Be3 Be6 19.Ng3 is a promising endgame for White, as Black is not in time to break with ...d6-d5) 15.g5 Nd7 16.a3 (Besozzi-Matozo, email 2010) 16...Ne5 17.f4 Ng4 18.Bd2± and the g4-knight is out on a limb. 14.Bd3?! White is still doing well after this automatic move, but we can go for the jackpot! 14.a3! is very unpleasant for Black, who would need to play ...Rb8 to prepare ...b5-b4: 14...d5 (14...Rb8 is too slow after 15.h5 h6 16.g5 hxg5 17.Bxg5, prying open the kingside) 15.g5 Nh5 16.f4 (Houpt-Hassim, email 2005) 16...Nc4 17.Bxc4 dxc4 18.Nf5! exf5 19.Qxd7 and Black is in serious trouble. 14...b4 14...Nxd3 15.Qxd3 b4 16.Nce2 Qc7 17.Rdg1 e5 18.Nf5 Bxf5 19.exf5 Qc4= looks fine for Black – White’s kingside attack is made a little redundant by the fluid centre and trade of queens. 15.Nce2 d5?! This is not the first time Kozul has tried to make the ...d6-d5 break work in this variation, but in general White benefits from the structural transformation if we can play g4-g5 in reply. 15...a5 16.Nf4!² and g4-g5 is unpleasant for Black. 16.g5 Nh5 17.exd5 exd5 18.Nf4! Nxf4 19.Bxf4² Nxd3 19...Nc4!? 20.Qxd3 a5 20...Re8 21.Rhe1 Bc5 and trading rooks would minimise White’s advantage, as the greedy 22.Nb3 Bb6 23.Qxd5?! (23.Be3²) 23...Rxe1 24.Rxe1 Bc6 25.Qxd8+ Rxd8 gives Black full compensation for the pawn. 21.Nf5 Bxf5 21...Be6 22.Be5± forces the exchange anyway. 22.Qxf5 d4 23.Be5 Rc5 Better was 23...Qb6. 24.Qe4 24...f6? A blunder, but Black was losing a pawn for nothing anyhow. Trading queens with 24...Qd5 25.Rhe1 Qxe4 26.Rxe4 Rd8± seems the best drawing chance. 25.Bxd4 Rd5 26.Kc1!+– Threatening 27.Bxf6 among other moves. 26...fxg5 27.Bxg7 Rff5 28.Bh6 Qd6 29.Rxd5 Rxd5 30.Bxg5... 1-0 (38) 14.9 Wojciech Krzyzanwski 2242 Arkadiusz Wosch 2215 LSS email 2011 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 d6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f3 Be7 10.Kb1 Rc8 10...0-0 11.h4 Nxd4 12.Qxd4 b5 13.Qd2 Bc6 14.Ne2 Rc8 is our move order. 11.Nxc6 Bxc6 12.h4 b5 13.Ne2 0-0 14.Nd4 Bb7 15.g4 Nd7 16.Bxe7 Qxe7 17.Qe3² h6 A) Black is too slow with his own queenside pawn storm: 17...b4?! 18.g5 Nc5 19.h5 a5 20.g6!? fxg6 (20...h6±) 21.hxg6 h6 22.Bc4 Qf6 was Leko-Kozul, Tallinn 2016 – White played quite impressively for a blitz game, but with more time would have probably spotted 23.Nf5! d5 24.exd5 Qxf5 25.dxe6 Ba6 26.Rxh6! ending all resistance; B) 17...Ne5 18.h5 gave White two wins in correspondence. A possible improvement is 18...h6 19.Rg1 f6, but it looks ugly, and 20.Bh3ƒ, threatening g4-g5, continues the pressure. 18.Rh2! A subtle move, but switching to central pressure with Rhd2 makes sense when g4-g5 is met with ...h6-h5. 18...Rfe8 18...Rfd8!? 19.c3 Red8?! Moving this rook to d8 in two moves already suggests that Black is unsure of his plan. 19...Ne5 20.Be2 Qc7 might be best, but I would still prefer White after 21.Rf2!, intending f3-f4. 20.h5!? While not a top choice of the engine, strategically it makes sense to fix Black’s structure for a coming g4-g5 break. 20.Be2² with ideas of g4-g5 and f2-f4-f5 was the alternative. 20...Qg5?! This just loses time, and I would prefer 20...Qf6, so that ...d6-d5 may be played without allowing e4-e5. 21.f4 Qc5 22.Qe1 22.g5! hxg5 23.fxg5± 22...Nf6 22...a5! 23.Bxb5 e5 24.Bxd7 Rxd7 25.Nf5 exf4 26.Rhd2 Rcd8 is not so clear. 23.Bd3 It would be too risky to take on g4 and open the g-file for White’s attack, but it’s hard to offer Black good advice. 23...b4 24.Nb3 Qb6 25.cxb4 Nxg4 26.Rg2 Nf6 27.Qg3! Nxh5 28.Qg4 The h5-knight finds itself embarrassed. 28...Qxb4 29.f5! 29.Qxh5 Bxe4 gives Black some counterplay – it’s better to keep the initiative. 29...exf5 30.Qxf5 Rc5 31.Nxc5 Qxc5 32.Rc2 Qxf5 33.exf5± The rook outpaces the knight and pawns in such an open position. White won after 71 moves. 14.10 Alexandar Parushev 2314 Petko Petkov 2168 ICCF email 2011 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f3 Rc8 10.Nxc6 Bxc6 11.Kb1 Be7 12.h4 b5 13.Ne2 0-0 14.Nd4 Bb7 15.g4 Qc7 16.Bd3² Rfd8 The engine suggests two retreats in a row, but after 16...Bd8 17.h5 Nd7 18.Bxd8 Rfxd8 19.g5 White’s initiative is obvious; 16...Rfe8 17.c3!?N (I really like this move to hold back Black’s queenside play and stabilise the centre) 17...Nd7 18.Bxe7 Rxe7 19.h5 d5 20.h6 g6 21.Rhe1ƒ with the much more flexible position. 17.c3! e5 17...Re8 18.h5 Nd7 19.Bxe7 Rxe7 20.Bc2 Ne5 (Varberg-Jorgensen, email 2011) 21.Qf4!N 21...Nd7 22.Bb3± creates a challenge for Black to get out of g5-g6. 18.Nf5 d5 19.Qe2!± dxe4 20.fxe4 White’s pieces are inexorably active. 20...Kh8 21.Rdf1 b4 22.Bxf6 gxf6 23.c4 Rxd3 24.Qxd3 Qxc4 25.Qxc4 Rxc4 26.Rc1! Bxe4+ 27.Ka1 Rxc1+ 28.Rxc1+– Black is OK on material, but his boxed in king and e7-bishop are decisive problems. 28...h5 29.Rc7 hxg4 30.Ng3 Bd5 31.Rxe7 Be6 32.Rc7 Kg7 33.Rc5 Kg6 34.b3 Bd7 35.Kb2 Be6 36.Kc2 Black resigned. 14.11 Martin Müller Alves 2325 Herve Daurelle 2243 LSS email 2011 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f3 Be7 10.h4 b5 11.Kb1 0-0 12.Nxc6 Bxc6 13.Ne2 Bb7 14.g4 Qc7 15.Nd4² Rfe8 15...Rac8 16.Bd3 – see the previous two games. 16.Bd3 b4 This pawn move doesn’t help as ...a6-a5 allows Bb5/Nb5, but otherwise 16...Nd7 17.Bxe7 Rxe7 18.h5 favours White, as does 16...Rad8 17.c3 e5?! (17...Nd7 18.Bxe7 Rxe7 19.h5 Ne5 20.Be2² Zatko-Taner, email 2011) 18.Nf5 d5 19.Qe2! dxe4 20.Bxf6 Bxf6 21.Bxe4± and the f6-bishop is stuck. 17.Rc1 Cautious, we could already go for the jugular with 17.h5!? Rac8 18.Rhg1±. 17...Rac8 18.h5 Red8 19.Be3 d5 20.e5! Nd7 21.f4 Nb6 22.g5 Nc4 23.Bxh7+! Forcing open the kingside. 23...Kxh7 24.g6+ Kh8 25.Qh2+– Bg5 26.fxg5 Qxe5 27.Qxe5 Nxe5 28.Bf4 Nd7 29.gxf7 e5 1-0 Chapter 15 The 6.h3 Najdorf 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6! 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6! The Najdorf is Black’s strongest defence to the Open Sicilian, because Black is more flexible than in the other systems we’ve seen – he can play ...e7-e6, ...e7-e5 or ...g7-g6, depending on our next move. It won’t be possible to prove a serious advantage against this move; however, I have found a variation that gives White the easier position to play in all lines. 6.h3! I have made the Adams Attack my main recommendation, as our g2-g4-g5 expansion retains the same spirit as the English Attack. 6.Be2 is my secondary recommendation. There’s no doubt that frequent Najdorf players will work hard to neutralise the ideas in this book, so a back-up line is essential to avoid particularly targeted preparation. Rare sixth moves A) 6...h5?! 7.Bg5!? is a much improved 6.Bg5 for White; B) 6...b5!?... is an underestimated move I prepared for a recent tournament, with the point that ...e7-e6 can be delayed in some instances: B1) After the consistent 7.g4 Bb7 8.Bg2 Black is not forced to transpose to 6...e6 with 8...e6, but can prefer 8...Nc6!? with interesting play: 9.Nxc6 Bxc6 10.g5 Nd7 11.Be3 Rc8=; B2) 7.Nd5 e6 8.Nxf6+ Qxf6 9.g3 e5! is also annoying: 10.Nb3 (10.Ne2 d5! 11.Qxd5 Ra7°) 10...Be7 and Black’s position looks healthy; B3) 7.Bd3!? Bb7 8.0-0 is interesting, but I couldn’t crack the flexible 8...Nbd7!, for instance: 9.b4!? (or 9.Re1 Ne5!) 9...Qc7 10.Bb2 e6 11.a4 bxa4 12.Qe2 Be7 13.Nxa4 0-0= and Black has a better version of our 5.Nc3 Paulsen line; B4) 7.a4 b4 8.Nd5 e6 (8...Nxe4 9.Bc4! e6 10.0-0 Bb7 11.Nxe6 fxe6 12.Re1 Nc5 13.Qh5+ g6 14.Qg4 Bxd5 15.Bxd5 Ra7 16.Bxe6 Nxe6 17.Rxe6+ Re7 18.Bg5 with a tremendous attack) 9.Nxf6+ Qxf6 10.Bd3 Be7 (10...Bb7 11.0-0 Nd7 12.Nb3!² with the idea of Na5 would suit perfectly) 11.0-0 0-0 12.Be3 Bb7 13.Qd2 a5 14.f4 Nd7 15.Nb3 Nc5 16.e5 Qh4 17.Nxc5 dxc5 18.Kh2 Rfd8 A draw was agreed soon in Lobanova-Falatowicz, email 2011, but perhaps 19.Qe2! can offer White a tiny edge with her space advantage. C) 6...Nc6 7.g4 Qb6 8.Nb3 e6 9.Be3 Qc7 is an improved version of the 6.f3 Qb6 variation for White, as we didn’t need to prepare Be3: 10.f4 b5 11.Bg2 – see Caruana-Karjakin (although I think 11.a3! may be more precise); D) 6...g6 is far from silly as ...a7-a6 feels slightly more useful than h2-h3 in a Dragon, but I still prefer White’s set-up: 7.g4 Bg7 8.Bg2 0-0 (8...h5 9.g5 Nfd7 10.f4!?N 10...Nc6 11.Nde2 is a new approach that gives White an edge, e.g. 11...0-0 12.f5! Qa5 13.0-0ƒ and White’s kingside space and attacking chances outweigh the e5-outpost) 9.Be3 Nc6 (9...Nbd7?! 10.0-0 Ne5 11.b3!± puts the blot on Black’s knight) 10.Qd2² I analyse this in Radjabov-Smirin, where we’ll see ways for Black to test White. 6...e5 7.Nde2 Introducing the pure Najdorf 6...e5 (matching White’s central occupation) 7.Nde2 (7.Nb3 Be6 8.Be3 is more in the spirit of the English Attack, but I haven’t found an iota of an edge against 8...Be7 9.Qf3 (or 9.f4 Nc6! 10.f5 Bxb3 11.axb3 Nb4=) 9...0-0 10.g4 a5!, to note one problem line) A) 7...Be7 8.g4 h6 (8...0-0 9.Be3! gives White an improved English Attack, see Swiercz-Kempinski, Poland tt 2015) 9.Bg2 Now 9...Be6 transposes to 7...Be6, whereas 9...b5 (9...Nbd7 gives the extra, unpleasant option of 10.a4!?N) 10.Ng3 g6 11.Be3 Nbd7 12.0-0 Bb7 13.Nd5 Nxd5 14.exd5 represents White’s strategic dream – he can elicit weaknesses on both flanks with a2a4 and f2-f4, while Black’s king remains insecure; B) 7...Be6 has a bad reputation, but requires precise play to demonstrate. 8.g4 and now: B1) 8...h6 9.Bg2 Nbd7 I’ve goofed around with this in blitz as Black, as most players mistakenly castle kingside, but we can change tack with 10.Be3 Rc8 11.Qd2! Be7 (11...Qa5 just misplaces the queen after 12.a4², when castling kingside works after all) 12.0-0-0 b5 13.Nd5 Bxd5 14.exd5 with a vastly improved English Attack type of position, see Biedermann-Panyushkin, email 2014; B2) 8...d5?! 9.exd5 Nxd5 is Black’s most common reply, but he can’t avert a depressing endgame: 10.Bg2 Nxc3 (in the endgame after 10...Bb4 11.0-0 Bxc3 12.Nxc3 Nxc3 13.Qxd8+ Kxd8 14.bxc3 White has a strong initiative, as addressed in Jensen-Cantelli, email 2012) 11.Qxd8+ Kxd8 12.Nxc3 12...Nc6 (12...Kc7 may be a better try, but 13.f4! Be7 14.f5 Bh4+ 15.Kf1 Bc4+ 16.Kg1 f6 17.Be3ƒ retains a large initiative – in particular the h4-bishop remains out of play) 13.Be3 Kc7 (13...Bb4?! 14.0-0-0+ Ke7 15.Nd5+ Bxd5 16.Bxd5+– is even worse) 14.Nd5+ Bxd5 15.Bxd5 f6 16.0-0-0 Be7 17.Be4 Rad8 18.c3± White has the bishop pair advantage and the more flexible structure on both flanks, which is almost enough to win in the ‘hypertheoretical’ sense; B3) After 8...Be7 9.Bg2 (9.g5!? Nfd7 10.h4 is worth exploring, as 10...h6 11.gxh6 gxh6 12.Be3 Nf6 13.Qd2 looks good for White) we have a final branching: B31) 9...Nc6 10.Nd5! is unpleasant as Black can’t play ...Nxd5, and after 10...Bxd5 11.exd5 Na5 12.0-0 0-0 13.Ng3± none of Black’s pieces are well placed; B32) Against the 9...Nbd7 set-up, I find kingside play to be the most effective: 10.Be3 0-0 (10...h6 11.Qd2! can transpose to 8...h6 after 11...Rc8. Otherwise, 11...0-0 12.0-0-0 b5 13.Kb1 Qc7 14.Nd5 Bxd5 15.exd5 is as usual a fantastic opposite-side castling position for White) 11.g5 Nh5 12.h4!N 12...g6 Otherwise 13.Bf3, but now 13.Nd5 f6 14.Qd2ƒ secures White’s central domination; B33) 9...0-0 10.Ng3 Nbd7 (after 10...b5 11.Be3 Nbd7 12.g5 Ne8 13.h4 Nb6 14.Nf5 Nc4 15.Bc1 White can follow the model game Anikeev-Gluhov, email 2012, as his flank play is clearly stronger) 11.g5 Ne8 12.h4 Rc8 13.Nf5 g6 14.Nxe7+ Qxe7 15.h5 White had the bishop pair advantage and some initiative in Ilyasov-Zakharov, email 2012. C) 7...b5!? This has been tried by some strong GMs lately, but it was dealt a blow in Ragger-Xiong, Wijk aan Zee 2017: 8.Ng3! (8.Nd5!? Nxe4 9.g3° as in Baklan-Duzhakov, Utebo 2017, also looks promising for White): C1) 8...Bb7 9.Bg5 Nbd7 10.Nh5!ƒ wins the battle for d5, whereas; C2) 8...Nbd7 9.a4 b4 10.Nd5 Bb7 11.Nxb4!N 11...Nc5 (11...Nxe4 12.Nxe4 Bxe4 13.a5² is similar, but perhaps the lesser evil) 12.a5 Ncxe4 13.Nxe4 Nxe4 14.Nd5 Be7 15.Bc4 Nf6 16.Be3± ensures White’s control over the centre; C3) 8...Qc7 (now Nd5 can be safely chopped off) 9.Bd3 C31) 9...g6!? 10.Bg5 Nbd7 11.0-0 Bg7 was Motylev-Sarana, Tallinn 2016. Once again, I like the plan 12.Qd2! 0-0 13.b4 Bb7 14.a4 Rfc8 (14...bxa4 15.Nxa4 showcases White’s positional objective) 15.axb5! Qxc3 16.Qxc3 Rxc3 17.bxa6 and Black is unable to keep his extra piece: 17...Bxa6 18.Bxa6 Rxc2 19.Bd3 Rxa1 20.Rxa1 Rb2 21.Rb1 Rxb1+ 22.Bxb1 It’s not much of an endgame edge, but the bishops give White pressing chances; C32) 9...Be6 10.0-0 Nbd7 and now an improvement on the aforementioned game is 11.Qf3! g6 12.Bd2 Bg7 13.b4! 0-0 14.a4 bxa4 15.Rxa4 and Black must forfeit the a6-pawn for insufficient compensation: 15...Nb6 16.Rxa6 Rxa6 17.Bxa6². The Move of the Computer Era – introducing 7...h5! 7...h5! It is important for Black to prevent White’s g2-g4/Bg2/0-0/Ng3 set-up, which is very harmonious for White. A) 8.g3 was the main trend until some Vachier-Lagrave games showed 8...Be6 9.Bg2 b5! 10.0-0 Nbd7 11.Be3 Be7= to be a particularly problematic line for White’s aspirations, as Nd5 only liquidates White’s ‘outpost’; B) 8.Ng1 was analysed by Jeroen Bosch in a ‘Secrets of Opening Surprises’ article, but such moves shouldn’t constitute the long-term foundation of one’s repertoire; C) 8.Nd5!? Nxd5 (8...Nxe4 9.Be3 Nd7 10.g3 Nef6 11.Nec3 b5 12.Bg2 Rb8 13.Bg5 b4 14.Ne4 Bb7 15.Nexf6+ gxf6 (Santos Etxepare-Wharam, email 2010) 16.Be3!? gives excellent compensation for the pawn) 9.Qxd5, as analysed in Anand-Topalov, Leuven 2016, has merit though; D) 8.Bg5! As often happens in opening theory, the old system becomes the new! White’s plan of dominating the d5square is as simple as it is effective. D1) The main move 8...Be6 will be considered in the next section; D2) If 8...Nbd7? 9.Nd5±; D3) 8...Be7!? requires a different plan from White: 9.Ng3 D31) 9...g6 stops Nf5 but is a bit weakening: 10.Bc4 Be6 (10...Nbd7 11.a4 Nc5 12.0-0 Be6 13.Bxe6 Nxe6 14.Bxf6 Bxf6 15.Nd5² saw White achieve his positional objectives in Amonatov-Idani, Urmia 2016) 11.Bxe6 fxe6 12.Qd2² We’ll see why White is better in Melkumyan-Raghunandan, London 2016; D32) 9...h4 10.Nf5 Bxf5 11.exf5 Nbd7 (11...Nc6 12.Bc4 Nd4 13.0-0! Nxf5 14.Bxf6 Bxf6 15.Qd5 Qe7 16.Rad1 gives White such light-square domination for the pawn that he can claim an objective advantage) 12.Bc4 Rc8 13.Bb3 (Black has to resort to some quite unusual moves to challenge White’s light-square bind) 13...Rh5! 14.Qd2 Nc5 15.0-0 Ng8 16.Be3 We are sacrificing a pawn, but we obtain great central control for it: D321) 16...Nxb3 17.axb3 Qd7 18.Nd5 Bd8 19.Rfd1 Ne7 20.Qe2 (or 20.c4 Nxf5 21.b4°) 20...Rxf5 21.Nc3 is a typical line, where Black’s pieces are awkward and White’s compensation is enough for a pull; D322) 16...Rxf5 17.Nd5 Nf6 18.Bc4 transposes to 16...Nf6; D323) 16...Nf6 17.Bc4N 17...Rxf5 18.Nd5! Nxd5 19.Bxd5 Qd7 20.c4 Ne6 21.Rac1² White has a perfect bind on the light squares, and it helps that the f5rook is quite misplaced. Anand’s queenside castling wrinkle 8.Bg5 Be6 9.Bxf6 Qxf6 10.Nd5 Qd8 (10...Bxd5?! 11.Qxd5 Nc6 12.Nc3 Be7 13.Bc4 Rc8 14.Bb3² was a thankless defensive task for Black in Gu-Ding, Yangzhou 2016) 11.Qd3! It is queenside castling that has changed the variation – before a famous 2015 Anand game, 11.Nec3 was preferred. Returning to 11.Qd3: A) 11...g6 12.0-0-0 will almost certainly transpose to a knight development. If 12...Bh6+ 13.Kb1 0-0 14.g4! is a handy trick: 14...h4 15.f4 exf4 16.Nexf4²; B) 11...Nc6 12.0-0-0 g6 (12...Rc8 is a normal move, but we might try to exploit Black’s delayed kingside development by opening the position: 13.f4!?N (13.Kb1 Bxd5 14.Qxd5², as considered in Hansen-Carstensen, Skorping 2017, would be normal) 13...Ne7 14.Nec3 Bxd5 15.Nxd5 Nxd5 16.Qxd5 Qc7 17.c3 exf4 18.Kb1 Be7 19.Be2 h4 20.Qf5 0-0 21.Qxf4 Qb6 22.Rd3 Rc5 23.Bd1! Qb5 24.Bc2² White’s bishop will be stronger than Black’s once it reaches b3) 13.Kb1 and now: B1) 13...Bh6 14.f4 Qa5 15.a3 Bg7 16.Qf3! with the threat of 17.f5 incites concessions from Black; B2) After 13...Rc8 14.f4!? (14.h4 Bg7 transposes to 13...Bg7) 14...exf4 15.Nexf4 Bg7 16.Be2 0-0 17.c3 White has a nice grip on d5 and the d6-pawn is weak, which outweighs Black’s bishop pair and e5 outpost; B3) 13...Bg7 14.h4 It is important to fix the kingside, so we can meet ...0-0 with f2-f3 and g2-g4. 14...Rc8 (or 14...0-0 15.g3 Bxd5 16.Qxd5 Qb6 17.Rh2 Rfc8 18.Qb3! Qxb3 19.axb3 White has a risk-free advantage with the better bishop and a weakness on d6 to target) 15.g3 b5 In the game Oparin-Gelfand, Moscow rapid 2015, Black proved successful, but I found a new idea to discourage kingside castling: 16.f3!?N 16...Na5 (16...0-0?! 17.g4! is the point) 17.Qa3!² and Black’s pawns come under fire with Ne3. C) 11...Nd7 12.0-0-0 Compared to a Sveshnikov, things may not seem so bad for Black, but Nepomniachtchi’s difficulties from this position (losing twice to Anand) suggest that Black’s life is not so rosy in practice. 12...g6 is his best move, and will be treated in the next section. For now, the alternatives: C1) 12...Qa5?! 13.Nec3 b5 14.a3 left Black nothing better than the sad 14...Rb8 15.Kb1 Qd8 in Alonso-Lagar, Rosario 2015: 16.Qe3±; C2) 12...Nf6 13.Nec3 Rc8 14.Kb1 Nxd5 15.Nxd5 Be7 is a rather natural way to develop, but White retains his pressure with 16.f4! Bxd5 17.Qxd5 Qc7 18.c3 exf4, which transposes to 11...Nc6!; C) 12...Nc5 feels a bit too forcing, but is not entirely silly. 13.Qf3 Bxd5 (13...Be7 14.Nec3² discourages a swap on d5) 14.Rxd5 Rc8 15.h4 g6 16.Kb1 b5 17.g3 Bg7 18.Nc3 Ne6 19.Bh3 b4 20.Ne2 and White has a nagging pull with his stronger bishop and structure; D) 12...Bxd5 13.Qxd5 was too passive in Ghosh-Shyam, Mumbai 2016: 13...Qc7 14.Nc3 Rc8 15.Kb1 Be7 16.Be2 b5 17.a3 and Black lacks an active plan, such as ...a6-a5/...b5-b4, with b5 covered many times; E) 12...b5 13.Nec3 (13.f4!?N) 13...Rb8 will be considered in the very recent game Anand-Nepomniachtchi, Leuven 2017; F) 12...Rc8 13.Nec3 g6 (13...Qg5+?! 14.Kb1 h4 15.Be2! is possible after all, as 15...Qxg2? (15...Nc5 16.Qf3²) 16.Qe3 Qg6 17.Rhg1 Qh7 18.Qa7! is already decisive) 14.Kb1 transposes to 12...g6. The main crossroads G) 12...g6 13.Kb1! (13.Nec3 is another move order, but I find it less precise because of 13...Nc5 14.Qe2 b5 15.Kb1 Rb8 16.a3 Bg7!=) G1) 13...Bh6 was Wei Yi’s flexible choice. 14.Nec3! Nc5 15.Qe2 See the model game Robson-Smuts, email 2012, which is a good demonstration of the computer’s difficulty grasping these strategic positions; G2) 13...Rc8 14.Nec3 is a crossroads where Black has trouble finding full equality, as if he plays ...b7-b5 he may find the rook is not ideal on c8. G21) 14...Nc5 15.Qf3 Bg7 16.Be2 h4 17.g3 b5 was Gu-Peng, Hainan 2016. Here I like 18.Qg2! Kf8 19.Bg4 hxg3 20.Qxg3² with persistent positional pressure; G22) 14...Rc5 seems a bit inaccurate, and we’ll see a model demonstration in Anand-Topalov, London 2015; G23) 14...Nb6!?, as played by Australia’s Dusan Stojic, is a solid choice: 15.g3!? (in the event of forcing play with 15.f4 Nxd5 16.Nxd5 Bxd5 17.Qxd5 Qc7 18.c3 exf4 19.Qd4 Rh7 20.Qf6 Bg7 21.Qxf4 Be5 22.Qf2 Qc5 23.Qf3 Qb6 24.Rd3 h4 the engines will give White a tiny edge, but it’s obvious to the human eye that Black’s position is impregnable) 15...Bg7 16.Ne3 Rc6 17.h4 White’s position is more pleasant, as Black’s knight is a bit offside, and castling tends to be well met by g2-g4!; G24) 14...Bh6 15.g3! This is my improvement over Anand-Vachier-Lagrave, Leuven 2017 (15.h4 Nb6!? 16.Nxb6 Qxb6 17.Qxd6 Qxd6 18.Rxd6 Bf8 19.Rd3 Bc5 20.f3 0-0 21.Nd5 f5° gives Black full activity for the pawn, in similar spirit to the Marshall): 15...Nc5 16.Qe2 h4 (if Black castles by hand, 16...b5 17.h4 Kf8 18.a3 Kg7 19.Bg2 grants White superior coordination) 17.Bg2 0-0 18.Bf3 and Bg4 gives White clearer play, as ...b5-b4 can always be held back with a2-a3. G3) 13...Nc5 14.Qf3 (14.Qa3!? is a more ambitious alternative, as we’ll see in Salem-Areshchenko, Sharjah 2017) 14...Bg7 15.Nec3 b5 This is a position where White has scored very well in the limited practice thus far, but objectively Black is fine. 16.Ne3!? (16.Rg1 Kf8! would anticipate White’s g4 idea; 16.Be2 Rb8 17.Nb4 Qd7=) 16...Rb8!N (by keeping the king in the centre, Black dodges the g2-g4 plan. After the natural 16...0-0 17.Be2 (17.Rg1 Bh6 18.Ncd5 Rc8 19.g4?! Bxd5 doesn’t convince me) 17...Rb8 18.h4 Qd7 19.Ncd5 the position definitely feels easier for White, who can prepare the g3-g4 break with g2-g3 and Qg2) 17.Be2 (I also checked 17.h4 Qd7 18.g3 (18.Ncd5 f5 19.exf5 gxf5 20.g3 Qf7 21.Bh3 e4 22.Qf4 Be5 23.Qg5 Rg8 24.Qh6 Rh8 25.Qg5 Rg8 is in the worst case a draw by repetition for Black) 18...a5 19.Ncd5 Kf8 20.Be2 Bh6= but I don’t see an improvement to the various repetitions proposed by the machine) 17...h4 (17...Bh6!? 18.Ka1 Bg5 19.b4 Na4 20.Nxa4 bxa4 21.c3 leads to complicated play) 18.g3 0-0 19.Rhg1 b4 20.Ncd5 a5 21.gxh4 Qxh4 22.Nc7 Qxe4 23.Qxe4 Nxe4 24.Nxe6 fxe6 25.f3 Nf2 26.Rxd6 Nxh3 27.Rg3 Nf4 28.Bc4 Rfe8 – as is inevitable for the Najdorf, with best play the position is just equal. The Keres Attack with h2-h3 and ...a7-a6 – initial developments 6...e6 7.g4 Black has multiple set-ups to choose from. 7...Nc6 8.g5 Nd7 transposes to 7...Nfd7, and 7...Be7 8.g5 Nfd7 is likewise transposing. 7...b5 8.Bg2 Bb7 9.0-0! scores badly for Black at a high level, as it is not easy for him to develop his kingside (9...Be7? 10.e5!). Previously it was assumed that White had to play 9.a3 or 9.g5 to mitigate ...b5-b4. Now: A) 9...Nc6?! runs into tactical problems: 10.e5! dxe5 (10...Nxd4 11.Bxb7 dxe5 would be a good exchange sacrifice, except we can decline the offer: 12.Ne4! Nxe4 13.Bxe4 Rc8 14.c3 Nc6 15.Qe2 Bc5 16.a4 and Black’s queenside is collapsing: 16...0-0 17.axb5 axb5 18.Qxb5±) 11.Bxc6+ Bxc6 12.Nxc6 Qc7 13.Qf3 Rc8 14.Nxe5 Qxe5 15.Qb7 Rd8 16.Qxa6 b4 17.Qb5+ Nd7 18.Qxe5 Nxe5 19.Nb5 Be7 Black has some compensation in the endgame, but White is definitely for choice after 20.Bf4 Ng6 21.Bh2²; B) 9...h6 10.Re1 forces 10...e5 to avoid a substantial disadvantage, as we’ll see in Carlsen-Gelfand, Nice 2008; C) 9...Qc7 is sensible to prepare ...Be7: 10.Re1 Be7 11.a4! This break is a compelling argument against 7...b5. C1) 11...b4 12.Na2! (the tempting 12.Nd5 exd5 13.exd5 0-0 14.g5 was successful in correspondence chess, but an improvement is 14...Nbd7!! as you might check for yourself) 12...h6 13.Nxb4 is better for White, as 13...d5?! 14.Nxd5 exd5 15.exd5 0-0 16.Nf5 gave White domination in Ameir-Hesham, Cairo 2016; C2) 11...bxa4 12.Rxa4 (this structure is almost always in White’s favour) 12...0-0 (12...Nfd7 13.Nd5! exd5 14.Nf5 d4 15.Nxg7+ Kd8 16.Rxd4± led to three wins in correspondence chess, the first being Walter-Gerhards, email 2009 – Black is unable to consolidate with the central king and weak d6-pawn) 13.Rb4! 13...Ne8 (13...Nfd7? is refuted by the same 14.Rxb7 Qxb7 15.e5 d5 16.Nxe6! fxe6 17.Nxd5+– Zhou-Georgiev, Sunny Beach 2014) 14.Rxb7!? Qxb7 15.e5 d5 16.Nxe6 fxe6 17.Nxd5 Nc6 18.Nxe7+ Qxe7 19.Bxc6 Rc8 20.Bg2 White looks close to positionally winning, but the open king limits our advantage somewhat. D) 9...Nfd7 10.a4! bxa4 (10...b4 11.Na2 a5 12.c3 bxc3 13.Nxc3 gives White a stable advantage, as we’ll explore in Schnabel-Horvat, email 2013) 11.Rxa4 Be7 meets a gorgeous refutation: 12.Rb4!N 12...Nc5 (or 12...Ra7 13.Be3 Nc5 14.f4ƒ) 13.Rxb7! It is natural to be drawn to this, but the computer’s continuation is something else! 13...Nxb7 14.e5 d5 15.Nxd5!! exd5 16.e6! 0-0 17.exf7+ Rxf7 18.Ne6 Qd7 19.Qxd5 and amazingly, Black is unable to keep his extra material: 19...Bh4 20.Bg5 Qxd5 21.Bxd5 Rd7 22.Bxh4 Rxd5 23.Nc7 Rc5 24.Nxa8 Rxc2 25.Re1! White has good winning chances with his extra pawn in the endgame; E) 9...b4 is the principled try: 10.Nd5! exd5 11.exd5 (this is the development, first played in Karjakin-Van Wely, Nice 2008, that transformed 6.h3 into a critical answer to the Najdorf) 11...Be7 (the d5-pawn is poisoned: 11...Bxd5? 12.Re1+ Kd7 (or 12...Be7 13.Nf5) 13.Bxd5 Nxd5 14.Qf3+–) 12.g5 and now: E1) 12...Nxd5? 13.Nf5 Qd7 14.Bxd5 regains the piece with interest; E2) Returning the piece with 12...0-0 13.gxf6 Bxf6 doesn’t slow down White’s initiative: 14.a3! bxa3 (14...a5 15.axb4 axb4 16.Rxa8 Bxa8 17.Re1± left Black’s queenside pieces stuck and his pawns weak in Popov-Lu, China tt 2015) 15.Rxa3 Nd7 16.Be3N 16...Ne5 17.Nc6 Qd7 18.Bd4!± Black can’t live comfortably with the monster knight on c6; E3) 12...Nfd7 13.Nf5!? (I like this idea of playing for long-term compensation. 13.Nc6 Qc7 14.Nxe7 Kxe7 15.Qd4° will be covered in Dembo-Vlcek, Rethymno 2009, as Black is unlikely to survive White’s attack without thorough knowledge) 13...0-0 14.Qd4 f6 (14...Ne5? 15.f4+–) 15.Qxb4 From here the arising play becomes very concrete due to the material imbalance. 15...Bc8 (15...Nc5 16.Re1 Rf7 17.gxf6 Bxf6 18.Nxd6! Qxd6 19.Re8+ Rf8 20.Bf4 gave White a decisive attack in Belton-Muller, email 2011) 16.Re1 Ne5! 17.Nxe7+ Qxe7 18.f4 a5 19.Qc3 Qf7!N (Black must create kingside counterplay quickly, or he will be positionally worse; 19...Qd8 20.fxe5 fxe5 21.Re4 Bf5 22.Rc4 Na6 23.a3 Qd7 The game Gindl-Claridge, email 2008, was agreed drawn after 24.b4, but stronger is 24.Bd2!± when Black lacks the resources to perturb White’s king) 20.fxe5 fxe5 21.Be3 (possibly stronger, but riskier, is 21.b3!? Na6 22.Rf1 Bf5 23.Qxa5 Qh5 24.Qc3 Rac8 25.Qf3 when I prefer White, but this could of course be investigated much more deeply) 21...Bf5 22.Qd2 Nd7 23.Rac1² White’s extra material feels more significant than Black’s kingside counterplay. Meeting a flank attack with a central thrust 7...d5 8.exd5 Nxd5 is Black’s most common reply, but currently unfashionable: 9.Nde2 A) 9...Nxc3 10.Qxd8+ Kxd8 11.Nxc3 Bd7! is a solid option where White struggles to prove more than a nibble: 12.Bg2 Bc6 13.0-0 Bxg2 14.Kxg2 Nd7 15.Be3!?N 15...Rc8 16.Rad1 Bc5 17.Bf4 is pleasant for White though, as the weakness of d6 can be exploited by Ne4 and there’s no simple way for Black to chop wood and force a draw; B) 9...h5 10.Nxd5 exd5 gives White more than one route to an advantage. I like 11.gxh5!? Nc6 (11...Bc5 12.Bg2N 12...Qh4 13.Ng3 Be6 14.Bd2 Nc6 15.Qf3 gives White some pull in a complicated situation) 12.Be3! Bf5 (the obvious 12...Rxh5 13.Qd2! Be6 14.0-0-0 Bb4 15.c3 Bd6 16.Kb1² gives White some pressure against the IQP) 13.Bg2 Qf6 14.c3 0-0-0 We’ve been following Dobrica-Gulevich, email 2013. Now I offer the novelty 15.Nf4!? Be4 16.Qg4+ Kb8 17.0-0-0 Ne5 18.Qe2 Bxg2 19.Nxg2, which allows White to keep control; C) 9...Bb4 10.Bg2 0-0 (10...Nc6 11.0-0 Nxc3 12.Nxc3 Qc7 13.Qd3!?N 13...0-0 (13...h5!? is well met by 14.g5²) 14.Qc4 transposes to 10...0-0) 11.0-0 Nxc3 12.Nxc3 and now: C1) 12...Bxc3 13.bxc3 Qc7 14.Rb1! Qxc3 The game Adams-Vachier-Lagrave, St Petersburg 2013, demonstrated how passive Black is if he doesn’t grab the pawn: 15.Qd2!N 15...Qxd2 16.Bxd2 Nc6 (16...e5?! 17.f4! exf4 18.Bxf4 Nc6 19.c4 only opens the play up for White’s bishops) 17.f4 Rd8 18.Be3 Black is all tied up and faces a long struggle for the draw; C2) 12...Qc7 13.Qd4 and now: C21) 13...Bd6 is the major alternative, but it leads to an unpleasant endgame after the following semi-forced line: 14.Be3 Bd7 15.Rad1 Bh2+ 16.Kh1 Be5 17.Qb6! (the trade of queens complicates Black’s development) 17...Bc6 18.Qxc7 Bxc7 19.Ne4! Nd7 20.Nc5 Ne5. Now White has to keep the initiative, or Black will complete development and equalise easily: 21.f4 Bxg2+ 22.Kxg2 Nc4 23.Bc1 b6 24.Rd7 Rfc8 25.b3 Nd6 26.Nd3 b5 27.Bb2 Bb8 28.Bd4 White’s pieces were more active in Serazeev-Mignon, email 2013. Subsequently, 28...Kf8! was found, but 29.f5 exf5 30.Re1! retains noticeable pressure. After 30...Ne8 White might opt for a more patient approach with 31.c3!N 31...fxg4 32.hxg4, keeping control; C22) 13...Nc6 and now: C221) 14.Bxc6 Bxc3 15.Qxc3 gives White a slightly better opposite-coloured bishops endgame or middlegame: 15...bxc6 (15...Qxc6 16.Qxc6 bxc6 17.f4² is covered in Lobanov-Sekretaryov, email 2010) 16.b3!?² see Moreira-Silva Lopez, email 2011; C222) 14.Qc4!? keeps the pieces on the board. 14...Bd6 (14...Bd7?! 15.Bf4! e5 16.Nd5 Be6 17.Be3 placed Black’s position under duress in Aguera NaredoSemenenko, St Petersburg 2016) 15.Be3 Bd7 16.Ne4 Be7 17.a4 Rac8 18.c3 Qb8 (after 18...e5 19.a5!² we can follow Evtushenko-Kolodziejski, email 2010) 19.Qe2 Ne5 20.Bf4 Bc6 21.Rfe1 h6 22.Rad1 and White had slight pressure in Oseledets-Gomila Marti, email 2012. Note that the engine’s attempted improvement 22...f6 backfires to 23.g5! fxg5 24.Bh2 when it is hard for Black to escape the pin. The prophylactic 7...Nfd7 7...Nfd7 Not the most common move, but it’s easiest to group the transpositions this way: 8.g5 and now: A) 8...Nc6 9.Be3 Be7 10.h4 is overly submissive: 10...0-0 (it is too late to backtrack: 10...Qc7 11.f4 b5 12.Nxc6 Qxc6 13.Qd4! This is an extremely unpleasant attack. 13...Qc5 (13...0-0 14.h5 and h5-h6 is already close to a decisive attack) 14.Qd2 Qc6 15.a3±; this is as good as it gets in the Open Sicilian!) 11.f4 Black is in trouble, see the game OttesenFeldborg, email 2011; B) After 8...b5 9.a3 Bb7 10.h4 Black can choose from a few set-ups, though as usual transpositions exist. B1) 10...Nc5?! only misplaces the knight after 11.Bg2²; B2) 10...Nb6 11.h5 N8d7 (11...d5 just helps White activate his pieces with 12.Bg2!N 12...dxe4 13.Nxe4²) 12.Qg4!?N (I want to place the queen as actively as possible) 12...Rc8 13.Rh3 Ne5 14.Qg3ƒ Black has mobilised his queenside but lacks a target, whereas White is ready to prosecute his attack with f2-f4 and g5-g6; B3) 10...Nc6 11.Be3 Rc8 12.Nxc6 Rxc6 13.Qd4! Ne5 14.0-0-0 Nc4 15.Rh3 gave White a strong initiative in Blomqvist-Nasuta, London 2016. If 15...Qb6 16.Qd3! Nxe3 17.Rxe3ƒ and Kb1/f4-f5 is fairly effective; B4) 10...Be7 11.Be3 Nc6 (11...Nb6 12.Qd2 N8d7 13.0-0-0 Rc8 is covered in Evtushenko-Noble, email 2012) 12.Qd2 This position has been frequently discussed in GM games, but lately the top players haven’t fully neutralised White’s attack: B41) 12...Nde5 and other rare moves will be treated in Külaots-Raznikov, Riga 2013; B42) 12...0-0 13.0-0-0 can transpose to 12...Rc8 after 13...Rc8 14.Nxc6 Rxc6. Instead, 13...Nxd4 (or 13...Nc5 14.f3 Rb8 15.Kb1! Nxd4 16.Bxd4 Bc6 17.Qh2!² when g5-g6 gives White a strong attack in all lines) 14.Bxd4 Bc6 15.f4 Rb8 16.f5! shows that White is not limited to playing h4-h5 and g5-g6!: 16...exf5 17.Bg2 f4 18.Nd5 a5 19.Qxf4 Now we follow a couple of correspondence games: 19...b4 20.axb4 Bxd5 21.exd5 Ne5 (21...Rxb4 22.Qd2 Qb8 23.Bc3 Rb7 24.Rhe1 Bd8 25.Bh3 kept White in the driver’s seat in Kubicki-Smythe, email 2013) 22.Be4 g6 23.Qg3 Rxb4 24.c3 Ra4 This was eventually drawn in Riccio-Nickel, email 2010, but here White maintains the momentum with 25.b3! Ra1+ 26.Kb2 Rxd1 27.Rxd1²; B43) 12...Rc8 13.Nxc6 Rxc6 14.0-0-0 0-0 15.Kb1 (the most flexible; 15.f4 Qa8! 16.Bd4 Rc7 17.Bd3 e5 18.Be3 f5! gave Black full counterplay in Nepustil-Felkel, email 2011; 15.h5 Qa5= meanwhile sets up annoying ...Rxc3 sacrifices, as in Bromberger-Cheparinov, Reykjavik 2016) 15...Ne5 16.Rh3! Nc4 17.Qe1 Now we see the point of Rh3 – we can play Bc1 and prevent ...Nxa3 tricks! But after 17...Nxe3 18.Rxe3² White was well coordinated for the attack, as we’ll see in Nepomniachtchi-Grischuk, Sochi 2016. Slowing the kingside pawn storm – introducing 7...h6! 7...h6! This Keres Attack transposition is the engine’s first choice, but the h6-pawn can prove a hook for our attack if Black castles kingside. 8.Bg2 I predict 8...Be7! to become the main trend against 6.h3, but first we should be ready for the alternatives: A) 8...g5?! is hard to trust, but we should be ruthless against such an ambitious dark-squared strategy: 9.Qe2 Nbd7 10.Rf1!?N (when Black plays ...Ne5, we are now ready with f2-f4) 10...Be7 11.Be3 Qc7 12.0-0-0 Ne5 13.f4 gxf4 14.Rxf4! (that’s why we played 10.Rf1!. After 14...Nfd7 White has the remarkable sacrifice 15.Nf5!? exf5 16.exf5 Nf6 17.Rb4! with a total bind on Black’s queenside development. I suppose it’s not necessary to credit Komodo with the idea...; B) 8...Nc6?! is an inaccurate move order because of 9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.e5!, splitting Black’s structure: B1) 10...dxe5 11.Bxc6+ Bd7 12.Bxa8 Qxa8 has given Black three draws in correspondence, but we can follow PotrataCastro Salguero, email 2012, at first: 13.Rg1 Bc6 14.Qe2 Bd6 15.g5! We can’t sit on our material, we must keep our initiative or our open king will become a factor. 15...hxg5 16.Qd3 Ke7 17.Bxg5 Bf3 18.Ne2 e4 19.Qd2 Qb8 20.0-0-0 Rc8 and now I like 21.Kb1!?±, not committing our queenside pawns until threatened; B2) 10...Nd5 11.exd6 Bxd6 (11...Qxd6 12.0-0 Be7 13.Ne4 Qc7 14.Qf3!?N stops ...Nf4, so that c2-c4 will come with more sting. The following forcing line also proves in White’s favour: 14...0-0 15.c4 f5 16.gxf5 Rxf5 17.Qg4 Nf4 18.Ng3 Rf8 19.Bxf4 Rxf4 20.Qg6 Rf6 21.Qe8+ Rf8 22.Qxc6 Qxc6 23.Bxc6 Ra7 24.b3² and the extra pawn outweighs the bishop pair) 12.Ne4 (White has the better structure after c2-c4, kicking Black’s pieces back) 12...Be5 13.c4! Nf4 14.Bxf4 Bxf4 15.Qf3 Qc7 16.Nd6+! Ke7 17.Qxf4 Qxd6 18.Qxd6+ Kxd6 19.0-0-0+N 19...Kc7 20.Rd2!ƒ Black experiences constant pressure due to his passive pieces and worse structure. C) 8...Qc7!? is a tricky Movsesian idea, preparing ...b7-b5 while keeping flexible: 9.Qe2 Nc6 10.Be3 and now: C1) 10...Nxd4 11.Bxd4 e5 12.Be3 Be6 gave Movsesian two draws, but it’s passive after 13.0-0-0 Rc8 14.Kb1 Be7 15.f4 exf4 16.Bxf4 0-0 17.Nd5 (Svidler’s 17.e5² is also very decent) 17...Bxd5 18.exd5 and White’s flank play is much better because of the extra central space, Gerasimov-Giobbi, email 2007; C2) 10...Be7 11.f4 is covered under 8...Be7; C3) 10...Bd7!? 11.f4 b5 is an ineffably annoying move order if we want to castle queenside. Fortunately, we can revert to kingside castling: 12.a3!N 12...Be7 13.Nb3 Rb8 14.0-0 0-0 15.Rad1² with good attacking chances on the kingside, based on h3-h4/g4-g5; C4) 10...Ne5 C41) 11.0-0-0 Nc4 12.Kb1 Bd7 (12...e5 13.Nf5 Be6 14.Bc1! was a bit better for White in Lukesova-Fajs, email 2009) 13.f4 may be the most accurate move order, to nullify 12...e5; C42) 11.f4 Nc4 12.0-0-0 The problem for Black is his knight manoeuvre is time-consuming without achieving enough in return. C421) 12...Nxe3 13.Qxe3 Be7 (the second knight’s dance 13...Nd7 14.h4 Nb6 15.g5 Nc4 looks too slow after 16.Qd3 hxg5 17.hxg5 Rxh1 18.Rxh1±) 14.Kb1 Nd7 15.h4 Nb6 16.g5 Bd7 17.g6!N White dreams of achieving this break while Black’s king is in the centre. 17...0-0 Now White can choose between 18.Bh3± and 18.f5!?; C422) 12...e5!? 13.Nb3 (13.Rhe1!?N is a beautiful piece sacrifice, but insufficient for an edge after 13...Nxe3 14.Qxe3 exd4 15.Qxd4 Be6 16.f5 Nd7 17.fxe6 fxe6 18.Rf1 Ne5=) 13...Bd7 14.Rd3N 14...Nxe3 15.Qxe3² Black’s position will soon experience pressure from fxe5 and Nd5; C423) 12...Bd7 13.Kb1 and now: C4231) 13...e5 14.Nb3 Rc8 15.Rd3! b5 (15...Nxe3 16.Qxe3 was also bad for Black in Ilyasov-Kozlov, email 2009) 16.g5 hxg5 17.fxg5 Nh5 18.Nd5 Qb7 was the model game Shirov-Gelfand, Monaco 1999. Almost anything is good for White here, but I like 19.g6!?±, ignoring all Black’s ideas!; C4232) 13...Rc8 14.Bc1± This line is simply unplayable for Black, as we’ll understand from Skrobek-Ciesielski, email 2006. The equaliser 8...Be7! I predict this will become the main trend within 6.h3. 9.Be3 As a rule of thumb, we should play f2-f4 before 0-0 to avoid 9.0-0 g5!=. 9...Nc6 10.f4! 10.Qe2 Nxd4 11.Bxd4 e5 12.Be3 b5= has a solid reputation for Black. 10...Nd7 10...Qc7?! is a tempo Black can’t afford against such an aggressive set-up: 11.Qe2 and now: A) 11...Bd7 12.0-0-0 Rc8 13.Kb1 b5 14.a3 Na5 15.Bc1 Nc4 16.Na2!? kills Black’s attack, while White is ready to play h3-h4/g4-g5 as soon as Black castles, or e4-e5 if Black doesn’t; B) 11...Nxd4 12.Bxd4 e5 13.Be3± See Movsesian-Akopian, Yerevan 1996. 11.0-0 The computer indicates that Black is completely fine, but it requires great precision to demonstrate this, while White has several tries. 11...0-0 The trend shifted here after the 11...Nxd4 12.Qxd4 0-0 (12...Qc7!? 13.Qd2 b5 is untested, but doesn’t affect the nature of the play) 13.Qd2 Rb8 14.Ne2 b5 15.Rad1= of Anand-Vachier-Lagrave, Stavanger 2015, which we analyse in the Game Section. I can’t claim White is better, but 2/2 at the super-GM level is encouraging. White was struggling a little in recent games, so a totally new direction is called for: 12.Nxc6!?N The position in the main line 12.Nce2 Nxd4 13.Nxd4 e5 14.Nf5 exf4 15.Bxf4 Ne5= followed by ...Bxf5 could even be considered easier for Black to play. 12.Nf3 b5= is the latest attempt, but White’s excellent score is not because of the opening. 12...bxc6 13.Na4 White switches to positional play, using his space advantage. 13...Bb7 Black is not in time to free his bishop with 13...a5?! 14.c4 Ba6 15.b3². 14.c4 c5 15.Qe2 Bc6 16.Nc3 Qc7 17.Rad1 Rad8 18.Bf2 Rfe8 The engines tend to assess these structures as equal initially, but White has a permanent space advantage that is not so easy for Black to play around. Furthermore, after... 19.Bg3² White can choose between h2-h4/g4-g5, e4-e5 and f4-f5, depending on Black’s set-up. Tests are required to determine Black’s best approach, but I think this is the maximum White can obtain against the 7...h6 8.Bg2 Be7 variation. Summary 2...d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3: 6...b5 – +0.25 6...Nc6 – +0.25 6...g6 – +0.30 6...e5 7.Nde2: 7...Be7 – +0.35 7...Be6 – +0.35 7...b5 – +0.25 7...h5 8.Nd5 – +0.20 7...h5 8.Bg5 – +0.10 6...e6 7.g4: 7...b5 – +0.30 7...d5 – +0.25 7...Nfd7 – +0.25 7...h6 8.Bg2: 8...g5 – +0.50 8...Nc6 – +0.35 8...Qc7 – +0.30 8...Be7 – +0.05 15.1 Fabiano Caruana 2811 Sergey Karjakin 2760 Zurich rapid 2015 (2) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 Nc6 7.g4 Qb6 8.Nb3 e6 9.Be3 Qc7 10.f4 b5 11.Bg2 11.a3!N is better, as we may not need Bg2 if we castle queenside: 11...Bb7 12.g5 Nd7 13.Qd2 Nc5 14.Bg2² Exchanging on b3 would open the c-file for our initiative. 11...Bb7 Likewise, Black has higher priorities than the fianchetto. 11...Nd7!N 12.0-0 Be7 13.e5 d5 14.Ne2 Nb6„ With ...Nc4 pending, Black has a decent version of the French structure. 12.g5 12.a3!? 12...Nd7 13.0-0 13.a3! 13...Nb6 14.Nd2 Be7= White’s problem is that when Black delays castling, the kingside storm would open White’s king more than Black’s. 15.Qe1?! 15.Qh5 g6 16.Qh6= 15...g6? White wasn’t threatening 16.f5 anyway, and besides 15...d5! (always check if this can be played!) 16.exd5 Nb4 17.d6 Bxd6 would grant a strong central initiative. 16.Qf2 Better was 16.a4 b4 17.Ne2. 16...Nd7 17.a4 b4 18.Ne2 0-0 19.h4 19.f5!? Nce5 20.f6 Bd8 21.Nd4, with mutual chances. 19...a5?! The tense nature of the play makes it hard to find the best moves quickly. 19...Rae8! 20.h5 Na5 is hard to understand, but the point is that after ...d6-d5 and an exchange on d5, the rook enters the fray. 20.c4 20.h5! 20...bxc3 21.Nxc3 Rac8 21...Nb4 was preferable. 22.Nb3?! 22.Nb5 Qb8 23.h5ƒ 22...Qb8 23.Nb5 Ba6³ 24.Qe2 Nc5 24...Nb6! 25.Nxc5 dxc5 26.f5 Nd4 27.Bxd4 cxd4 28.fxe6 fxe6 29.e5 Rc5–+ 30.Rae1 Bxb5 31.axb5 Rxb5 32.Rxf8+ Bxf8 33.Qc4 Rxe5 34.Rf1 Bc5 35.Kh1 Qb4 36.Qa6 d3 37.Qc8+ Kg7?? Turning the game 180 degrees. 37...Bf8 38.Qe8 Qe7–+ 38.Qc7+ Kg8 39.Qf7+ 1-0 15.2 Teimour Radjabov 2738 Ilya Smirin 2655 Baku 2015 (2) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 g6 7.g4 Bg7 8.Bg2 8.Be3 0-0 9.Qd2 b5 8...0-0 9.Be3 Nc6 10.Qd2² 10...Bd7 A) 10...Be6 11.f4 Nd7 12.0-0-0 Nxd4 13.Bxd4 Bxd4 14.Qxd4 Rc8 15.Kb1 b5 16.Qd2 b4 17.Nd5 Bxd5 18.exd5 Nb6 19.b3 – White will have the better flank play due to his central grip; B) 10...Nxd4!? 11.Bxd4 b5 12.Nd5! Nxd5 13.Bxg7 Kxg7 14.exd5 is again favourably transforming the structure: 14...Qb6 15.0-0-0 Ra7 16.f4 a5 17.Kb1 Rc7 18.Bf3²; C) 10...Nd7 forces perfect play from White to prove an edge: 11.0-0-0 (11.0-0 Nxd4 12.Bxd4 Bxd4 13.Qxd4 g5!= erects a dark-squared blockade; 11.f4 Nxd4 12.Bxd4 e5 13.fxe5 Nxe5 14.0-0-0 Be6=) 11...Nb6 (11...Rb8 12.f4 Na5 13.b3 b5 14.f5 Bb7 15.Bh6ƒ) 12.b3 Bd7 C1) 13.Rhe1N runs into 13...a5! 14.Nxc6 bxc6 15.f4 a4 16.e5 axb3 17.cxb3 Rc8 when Black’s game is already easier; C2) 13.f4 is the usual move, but I couldn’t crack 13...a5!N (13...Rc8) 14.Nxc6 (White should avoid 14.Kb1 a4 15.Ndb5 Nb4 16.a3 Bxc3 17.Nxc3 axb3 18.cxb3 Rxa3 19.Qb2 Qa8; 14.a4 Nb4= and ...Rc8 gives tremendous counterplay) 14...bxc6 15.f5 a4 16.h4 axb3 17.cxb3 Ra3 It feels much easier to play Black with his rapid queenside attack; C3) 13.Kb1N is a good prophylaxis against 13...a5, but not as useful against other tries: 13...Qc7 (13...a5 14.a4 Rc8 15.Ndb5 Nb4 16.Rc1 Na8 17.Nd4 Nc7 18.Rhd1²) 14.Nde2!? (if 14.Nxc6 bxc6 15.Bh6 Nc4! is a nice shot: 16.bxc4 Rab8+ 17.Ka1 Qb6 18.Rb1 Bxh6 19.g5 Bxg5 20.f4 Bxf4 21.Qxf4 Qd4 22.Qf3 Qxc4=) 14...Rfc8 15.Nd5 (15.Rc1 Na7! 16.f4 Nb5 17.Nxb5 axb5 18.c3 Ra3 gives Black the half-open files he needs) 15...Nxd5 16.exd5 Na7 17.c4 White’s pawn chain appeals to the eye, but it will get broken down with 17...Qd8! 18.Rc1 b5 19.c5 dxc5 20.Rxc5 b4!?=; C4) 13.Nxc6!N (it’s imperative to exchange the dark-squared bishops, before ...a5-a4 comes) 13...Bxc6 (13...bxc6 14.Bh6 a5 15.Bxg7 Kxg7 16.f4 a4 17.f5 is a much faster attack for White) 14.Bd4 Bxd4 15.Qxd4 Rc8 16.f4 Qc7 17.Kb2 a5 18.h4² White has an imposing position with the four pawns abreast. 11.0-0-0 This semi-automatic move may not be the best; I propose 11.f4 Rc8 12.Nde2!?N for the option of castling on either flank. Also, it makes sense to keep all the pieces on the board when we have more space: 12...b5 13.a3 Na5 14.b3 Bc6 15.0-0 would be discomforting for Black’s queenside pieces, for example. 11...Rc8 12.Nde2 12.f4 b5 13.e5 b4! 14.Nce2 Ne8 15.Kb1 Qc7 16.e6 fxe6 17.Bxc6 Bxc6 18.Nxe6 Qb7 19.Rh2 Be4 20.N2d4 a5! 21.Nxf8 Bxf8° Black had reclaimed the initiative in Milde-Franke, email 2014. 12...b5 12...Ne5 forces a draw: 13.b3 Qa5 14.Kb1 Nc4! 15.bxc4 Rxc4 16.e5 Rfc8! 17.exf6 Rb4+ 18.Ka1 Bxf6 19.Bd4 Rxd4! 20.Nxd4 Rxc3= Shpakovsky-Gerasimov, email 2012. 13.Nd5 13.Kb1! b4 14.Nd5² 13...a5 14.Bb6 This only loses time – after the superior 14.Kb1!? Nxd5 15.exd5 Nb4 16.c3 Na6 17.Bd4² Black’s pieces lack harmony. 14...Qe8 15.Kb1?! 15.Nc7 Qd8 16.Nd5 repeats. 15...Rb8! 16.Be3 Ne5! White can’t afford to lose tempi in such a sharp position – now Black has a clear initiative. 17.Bd4 Nc4 18.Qg5 Nxd5 19.exd5 e5 20.dxe6 fxe6 21.Bxg7 Kxg7 22.Ng3 Qd8 23.Qxd8 Rbxd8 24.Rhf1 d5 25.b3 Nd6 26.Kb2 b4 27.Rd2 a4 28.f4 a3+ 29.Kc1 Nb5 30.Ne2 g5 31.f5 Bc8 32.fxe6 Bxe6 33.Nd4 Nxd4 ½-½ 15.3 Dariusz Swiercz 2629 Robert Kempinski 2647 Poland tt 2015 (2) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e5 7.Nde2 Be7 8.g4 0-0 9.Be3 Nbd7 9...h6 10.Ng3 Be6 11.Bg2 Nbd7 12.Nf5 Bxf5 13.exf5 was the hugely favourable course of Rudenko-Sirobaba, email 2011: 13...Nb6 14.0-0 Nc4 15.Bc1 Na5 16.Nd5 Nxd5 17.Qxd5ƒ White’s light-square domination is a sight for sore eyes. 9...Be6 10.Bg2 transposes to 7...Be6. 10.Ng3 White could even play in English Attack style already: 10.g5! Ne8 11.Qd2 Nc7 12.Ng3 b5 13.a3± 10...b5 If 10...h6 11.Nf5 Nc5 12.Qf3 Bxf5 13.gxf5 offers the standard g-file attack, though 11.h4 or 11.g5 may be even stronger. 11.g5 Ne8 12.h4 Bb7 Better was 12...Nc7 13.a3 Rb8. 13.Nd5 13.Qd2!? f5 14.exf5 Bxh1 15.Nxh1± Rxf5 16.Bh3 Rf8?! 17.Bxd7 Qxd7 18.Qd5+ 13...Bxd5 13...g6 14.Qd2 Nc7 15.0-0-0 Nxd5 16.exd5 Nb6 17.Bxb6 Qxb6 18.Ne4± 14.Qxd5 Nc7 15.Qd2± White’s positional preponderance is apparent. 15...Ne6 15...g6 16.0-0-0 Ne6 17.Kb1± 16.0-0-0 16.Nf5 16...Ndc5 17.f3 g6 18.Kb1 Rb8 19.Rg1 19.Nf5! is thematic: 19...gxf5 20.exf5 Nf4 21.f6 Bxf6 22.gxf6 Nce6 23.Rg1+ Kh8 24.Qxd6 Qxd6 25.Rxd6± 19...Re8 20.Bh3 b4 21.Ne2 21.Nf5! 21...Bf8 22.h5 Qc7 23.hxg6 hxg6 24.Rh1 The h-file attack is too much to bear. 24...Na4?! 24...a5 25.Bxe6 fxe6 26.Nc1± 25.b3 25.Bxe6 fxe6 26.b3 Nc5 27.Ng3+– 25...Nc3+ 26.Nxc3 bxc3 27.Qh2 Bg7 28.Bxe6 Rxe6 29.f4 exf4 30.Bd4!+– Bxd4 31.Rxd4 Kf8 32.Qxf4 Qc5 33.Rd3 Ke7 34.Rf3 Rf8 35.Rh7 Kd7 36.Rxf7+... 1-0 (42) 15.4 Thomas Biedermann 2456 Boris Panyushkin 2256 ICCF email 2014 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e5 7.Nde2 Be6 8.g4 h6 9.Bg2 Nbd7 10.Be3 Be7 11.Qd2 Rc8 12.0-0-0 b5 13.Nd5 Bxd5 14.exd5² Nb6 14...0-0 15.Kb1 Nb6 16.b3 Qc7 transposes. 15.b3 Qc7 16.Kb1 0-0 17.Rhg1! White doesn’t waste a moment with his attack, and Black is promptly crushed like a bug. 17.Rc1 Rfe8 18.Ng3² 17...Nh7 18.Ng3 Rfe8 19.Ne4± Nd7 20.Rc1 Nhf6 21.g5 hxg5 22.Bxg5 Qb6 23.Be3 Qc7 24.Bh6 g6 25.h4 Nc5 26.Nxf6+ Bxf6 27.h5+– Storming the last barricades. 27...Na4 28.bxa4 e4 29.hxg6 bxa4 30.c3 Bxc3 31.gxf7+ Kxf7 32.Rxc3 Qxc3 33.Qf4+ Qf6 34.Bh3 Rb8+ 35.Kc1 Qxf4+ 36.Bxf4 Rb5 37.Rg5 Kf6 38.Be6... 1-0 (52) 15.5 Claus Jensen 2301 Alessandro Cantelli 2331 ICCF email 2012 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e5 7.Nde2 Be6 8.g4 d5 9.exd5 Nxd5 10.Bg2 Bb4 11.0-0 Bxc3 12.Nxc3 Nxc3 13.Qxd8+ Kxd8 14.bxc3ƒ Kc7 14...Nc6 15.f4 Kc7 16.fxe5 Nxe5 17.Bf4 f6 18.Rab1 Rab8 19.g5 Bc4 20.Rf2 Bxa2 21.Rb4ƒ 15.f4 f6 16.fxe5 fxe5 17.Be3 Nc6 18.Rfb1 Much like a Catalan endgame, Black can’t neutralise the g2-bishop’s pressure. 18...Rac8 After 18...Rae8 19.Rb2 Bc4 White won two correspondence games with 20.Bb6, but I’m also attracted to 20.Be4!?ƒ. 19.Rb6 Rce8 20.Rab1 Bc8 20...Rb8 21.a4± 21.Be4± Black is frozen in place and it’s hard for him to resist the bishop pair on an open board. 21...h6 22.c4 Ref8 23.c3 Rf7 24.a4 Rf6 25.Kg2 g5 26.R6b2 Kb8 27.Kg3 Na5 28.Bd5 Nc6 29.Rf2! Exchanges tend to optimise the bishop pair advantage. 29...Rxf2 30.Bxf2 Bd7 31.Bc5 Kc8 32.Rf1 h5 33.Be3 hxg4 34.hxg4 Ne7 35.Be4 Be6 36.Bd3 Rd8 37.Be2 Rg8 38.Rh1 Bd7 39.Bd1 Be6 40.Rh7 Nc6 41.c5 a5 42.Rh5 Rf8 43.Rxg5+– Rf1 44.Rg6... 1-0 (57) 15.6 Viswanathan Anand 2770 Veselin Topalov 2761 Leuven blitz 2016 (10) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e5 7.Nde2 h5 8.Nd5 Nxd5 9.Qxd5 9...Nd7?! 9...Nc6 10.Qd1 Be6 11.Nc3 A) 11...Rc8 12.Nd5 (12.Be2 g6 13.0-0 Bg7 14.Nd5 Bxd5 15.exd5 Nb8 16.c4 Nd7=) 12...Bxd5 13.exd5 Nb8 14.Be3 Nd7 15.Qd2 g6 16.0-0-0 Bg7= resembles the ...h7-h5 lines in the English Attack, where Black maintains the balance but White’s bishop pair gives him chances to outplay the opponent; B) The most natural play for both sides would be 11...Be7 12.Nd5 Rc8 13.c3 Bg5 14.Be2 Bxc1 15.Rxc1 Ne7 16.Ne3 g6, when I like 17.Rc2! Bxa2 18.Rd2 Be6 19.Rxd6 Qc7 20.0-0 0-0 21.Qd3 Rfd8 22.Rd1 Qxd6 23.Qxd6 Rxd6 24.Rxd6 with a symbolic edge for White; C) 11...Ne7!? 12.Bd3 d5 13.exd5 Nxd5 14.0-0 Nb4 (Anand-Nakamura, St Louis 2016) 15.Re1!? Nxd3 16.cxd3 Bd6 (16...Bc5 17.Be3 Bxe3 18.Rxe3 f6 19.Ne2 Qb6 20.d4²) 17.Be3 0-0 18.Qxh5 f5 19.d4 Qe8 20.Qxe8 Rfxe8 21.dxe5 Bxe5² Black’s bishop pair should keep him safe, but White has chances to win. 10.Nc3 Nf6 11.Qd1 11.Qb3!? constricts Black’s development and sets up Bc4: 11...b5 12.a4 Be6 13.Nd5 Nxd5 14.exd5 Bd7 15.axb5 axb5 16.Rxa8 Qxa8 17.Be2 Be7 18.0-0² Black’s b5-pawn is a target. 11...Be6 12.Bg5 Be7 13.Bxf6 Bxf6 14.Be2 g6 14...Rc8!= is better as Bxh5 is met by ...Qb6. 15.0-0 Rc8 16.Nd5 Bg5 16...Bxd5 17.Qxd5 Rxc2= was best, though White’s superior bishop gives him good compensation. 17.c3 0-0 17...Qa5!? 18.a4 Kg7 19.a5 h4?! 19...b5!? 20.axb6 Bxd5 21.Qxd5 Qxb6 is a nice trick to engineer queenside counterplay. 20.Ra4 20.Nb6 makes sense, to batten down the queenside. 20...Rc5 21.b4 Rc6 22.c4 Bf4 22...f5! was the correct way to generate counterplay, as in a Sveshnikov. 23.Ra3!? Qg5 24.Nb6 24.Qd3 Rfc8 25.Rc3 Bxd5 26.Qxd5² 24...f5?! Now this fails tactically. 24...Bd2! first is a nuisance. 25.b5 axb5 26.cxb5 Rc1? 26...Rxb6 27.axb6 Rd8± 27.Qxd6+– Rxf1+ 28.Bxf1 Bf7 29.a6 bxa6 30.bxa6 Rd8 31.Nd7 fxe4 32.a7 e3 33.a8=Q exf2+ 34.Kh1 1-0 15.7 Hrant Melkumyan 2633 Kaumandur Raghunandan 2423 London 2016 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e5 7.Nde2 h5 8.Bg5 Be7 9.Ng3 g6 10.Bc4 Be6 11.Bxe6 fxe6 12.Qd2² 12...b5 12...Nbd7!? 13.0-0 (13.0-0-0 b5 14.f3 0-0 15.Kb1 Rc8 16.Nce2 Nb6 17.b3 Nbd7= makes it difficult for White to open the kingside in his favour, because of 18.f4?! Nc5!) 13...Qc7 prepares queenside castling, but we can anticipate this: 14.Rab1!? (14.Rfd1 0-0-0 15.a4 Kb8 16.Qd3 d5 17.exd5 exd5 18.h4 e4 19.Qe2 Qc6=) 14...b5 (14...0-0-0 15.b4!ƒ and b4-b5 is the idea) 15.a3 0-0 16.Rbd1 and Black’s structure is less flexible, though other than that his position is okay. 13.0-0 0-0 14.a4 14.b4!? Nc6 15.a4 Rb8 16.axb5 axb5 17.Rfd1 keeps Black without a good break. 14...b4 15.Nce2 Qa5? 15...Nc6 16.Rad1 Ne8 17.Bxe7 Qxe7 18.f4 keeps Black on the defensive, as 18...exf4?! 19.Nxf4 Kh7 20.Nge2!ƒ only helps White. 16.Qd3? 16.Bh6 Rc8 17.f4± is powerful, as 17...Qc5+ 18.Kh1 Qxc2 19.Qe3 retains the queens for a decisive attack. 16...Nbd7 17.Qc4 17.Nc1!? 17...d5? This exposes Black’s weaknesses. 17...Kf7 18.exd5 exd5 19.Qd3² e4?! 19...Kg7 was better. 20.Qd2 Kh7 21.Nd4 Playing for positional control, but it was possible to hit d5 with 21.Nf4!±. 21...Qb6 21...Bd6 22.Nge2 Rae8² 22.Be3 22.Nge2² 22...Bc5 23.a5 Qd6 24.b3 Rac8 25.Rfd1 Ne5 26.Nf1 Rf7 27.Ne2 Nc6 28.Bxc5 Qxc5 29.Qe3 Qb5 30.Ra4 30.Rd2!? 30...Rff8?! 30...d4! 31.Nxd4 Nxd4 32.Rxd4 Rxc2= is right, with the trick 33.Raxb4 Nd5! in mind. 31.Nd4 Nxd4 32.Qxd4 Rxc2 33.Rxb4 Qxa5? 33...Qc5± was necessary, to cover the king. 34.Rb7++– Kg8 35.Ne3 Rcc8 36.Qe5 Rce8 37.Qg5 1-0 15.8 Mads Hansen 2444 Jacob Carstensen 2381 Skorping ch-DEN 2017 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 Nf6 4.Nc3 cxd4 5.Nxd4 a6 6.h3 e5 7.Nde2 h5 8.Bg5 Be6 9.Bxf6 Qxf6 10.Nd5 Qd8 11.Qd3 Nc6 12.0-0-0 Rc8 13.Kb1 Bxd5 14.Qxd5 b5 14...Qb6 15.Qb3 Qxb3 16.axb3 is a smooth endgame pull for White. 15.c3? This only creates a hook for Black’s wing attack. 15.Nc3 Be7 16.h4!² 15...Qb6 15...Be7= 16.f4 Be7 Better was 16...Rd8. 17.Ng3?! 17.fxe5 Nxe5 18.Qd4 Qxd4 19.Nxd4² 17...exf4?! 17...g6 applies ‘distance-4’ to the white knight. 18.Nxh5 0-0? 18...b4! was still messy, whereas the text just loses a pawn. 19.Nxf4± Bf6 20.Qb3 Be5 21.Nd5 Qa7 22.Be2 Rb8 23.Rhf1 Ne7 24.Nxe7+ Qxe7 25.Rf3 g6 26.Rdf1 Kg7 27.Bd1 a5 28.Qd5 a4 29.a3 f6 30.Be2 Rfc8 31.h4 Rc5 32.Qd2 Rh8 33.Rh3 Qe6 34.Rff3 Qg4 35.Rxf6 Qxg2 36.Rf7+ Kg8 37.Rhf3 Rxh4 38.Rf8+ Kh7 39.R8f7+ Kg8 40.Ka2 Qh2 41.Qg5 Black resigned. 15.9 Viswanathan Anand 2775 Ian Nepomniachtchi 2766 Leuven blitz 2017 (3) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e5 7.Nde2 h5 8.Bg5 Be6 9.Bxf6 Qxf6 10.Qd3 Nd7 11.Nd5 Qd8 12.0-0-0 b5 13.Nec3 13.Kb1!?N 13...Nc5 14.Qf3 may be the most accurate move order. 13...Rb8 14.Nb4 14.a3 g6 15.Kb1 Nc5 16.Qe2 Bg7 makes it hard for White to do anything on the kingside. 14...Qg5+?! 14...Nc5 15.Qd2 Qc8 16.f3 Be7 17.Kb1 0-0 18.Nbd5 Bd8 19.a3 h4= holds down the position effectively – White should go for g2-g3 but the attack develops slowly. 15.Kb1 Nc5 16.Qf3² Be7 17.Ncd5 17.h4 Qh6 18.Qe2² and g2-g3/Bh3 is a promising positional plan. 17...Bd8 18.Be2 Rb7?! 18...Qg6! keeps White busy. 19.Ne3! Qf4? The arising endgame is no good, but 19...Rd7 20.Nxa6! Nxa6 21.Bxb5 Nc7 22.Ba4 0-0 23.Bxd7 Bxd7 24.Rxd6 Be6 is also good for White, though in rapid anything can happen with a material imbalance. 20.Qxf4 exf4 21.Nf5 0-0 22.Nxd6 Rb6 23.e5 Nd7 24.Nd5 24.Nd3!? 24...Bxd5 25.Rxd5 Nxe5 26.Rhd1 Bc7 27.Bxh5± This book’s masterclass of opposite-coloured bishops endgames continues! 27...g6 28.Be2 Kg7 29.a3 Rfb8 30.c3 Kf8 31.Kc2 Rd8 32.Ne4 Rxd5 33.Rxd5 Ke7 34.Nc5 Rc6 35.a4 bxa4 36.Nxa6 Bd6 37.Ra5 f5 38.Rxa4 g5 39.Nb4 Rc8 40.Nd3 Ng6 41.Ra7+ Kf6 42.Ra6 Ke7 43.Bf3 Nh4 44.Bd5 g4 45.hxg4 fxg4 46.Ra4 Rf8 47.Re4+ Kd8 48.Re6 Kd7 49.Rh6 Nf5 50.Be6+ Ke7 51.Bxf5 Rxf5 52.c4 g3 53.f3... 1-0 (67) 15.10 Nigel Robson 2570 Iain Smuts 2262 ICCF email 2012 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 Ng4 7.Bc1 Nf6 8.h3 e5 9.Nde2 h5 10.Bg5 Be6 11.Bxf6 Qxf6 12.Nd5 Qd8 13.Qd3 Nd7 14.Nec3 g6 15.0-0-0 Bh6+ 16.Kb1 Nc5 17.Qe2 17...h4 17...Rb8 was successfully played before this game. I’m sure Robson had an improvement ready, but it may well be that Black is just fine: 18.h4 b5 19.a3 (19.Nb4 Qd7 20.Ncd5 Bg7= achieves little) 19...Bd7 and now: A) 20.Qf3 Bg7 21.Ne3 b4 22.axb4 Rxb4 gets messy after 23.Nc4 0-0 24.Rxd6 Qb8 25.Rxd7 Nxd7 26.Nd5 Rb5 27.g4 hxg4 28.Qxg4 Rxd5 29.exd5 Nf6 30.Qd1 Rd8 and Black has a healthy initiative for the pawn; B) 20.f3 a5 21.b4 axb4 22.axb4 Ne6 23.Qf2 Rb7 24.g4= is similar but perhaps an improved version of 20.Qe1; C) 20.Qe1!? a5 (20...0-0 21.Be2 a5 22.b4 axb4 23.axb4 Ra8 24.Kb2 Na4+ 25.Nxa4 bxa4 26.f3² represents White’s strategic aim, closing down the queenside and keeping the bishops out of play) 21.b4 axb4 22.axb4 Ne6 23.f3 0-0 24.g4 Nf4 25.gxh5 Nxh5 26.Kb2 when I find White’s position much easier to play due to the fixed weakness on b5, which can be targeted by Ra5. But the engine maintains 0.00 – possibly influenced by the open (but safe) white king, so this requires testing. 18.a3 0-0 19.Qe1 Rb8 20.g3 b5 21.Rg1! The kingside attack is quite dangerous as Black castled too soon. 21...hxg3 22.fxg3 Bd7 23.b4! Ne6 24.h4ƒ Nd4 25.Be2 f5 26.h5 gxh5 27.Rh1+– Black can’t bring his pieces to the kingside in time. 27...a5 28.Rxh5 Bg7 29.Bd3 f4 30.gxf4 Bg4 31.Rh1 axb4 32.axb4 exf4 33.e5 dxe5 34.Bh7+ Kf7 35.Qg1 Qd7 36.Rh4 Ke8 37.Rxg4 Rb7 38.Rg6 1-0 15.11 Viswanathan Anand 2796 Veselin Topalov 2803 London 2015 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e5 7.Nde2 h5 8.Bg5 Be6 9.Bxf6 Qxf6 10.Nd5 Qd8 11.Qd3 g6 12.0-0-0 Nd7 13.Kb1 Rc8 14.Nec3 Rc5 15.Be2 15.f4 exf4 16.Nxf4 Ne5 17.Qd4 Bh6! 18.g3 h4 19.Nxe6 fxe6 20.gxh4 Rc6= 15...b5? After 15...Nb6! White should keep Black’s knight dangling: 16.Ne3!? (16.Nxb6 Qxb6 17.g4 Qa5 18.a3 h4=; 16.g4 Bxd5 17.exd5 hxg4 18.hxg4 Rxh1 19.Rxh1 Bg7„) 16...Be7 17.h4! and Black remains tied down. 16.a3 16.f4 Bxd5 17.Nxd5 exf4 18.Qd4 Ne5 19.Nxf4± was a great opportunity to exploit Black’s slip. Indeed, Black often plays the bishop to h6 to nullify f2-f4. 16...Nb6 17.g4 hxg4 18.Nxb6 18.hxg4 Rxh1 19.Rxh1 Bxd5 20.exd5 Bg7 21.Ne4! Rxd5 22.Qc3 Qc8 23.Qf3ƒ gives fantastic compensation, as the rook on d5 is stuck. 18...Qxb6 19.hxg4 19.Bxg4 Bc4 19...Rxh1 20.Rxh1 Bg7 21.Qe3 Qb7?! 21...Rc6! 22.Qxb6 Rxb6= 22.Rd1 Qc7 23.g5² The long-term problem for Black is his passive g7-bishop. 23...Qc6 24.Rg1 Qd7 25.Qg3 Rc8 26.Bg4!? Bxg4 27.Qxg4 Qxg4 28.Rxg4² Bf8 29.Nd5 Be7 30.c3 Rc6 30...Rd8! 31.Nc7+ Kd7 32.Nxa6 Rh8 with mutual chances. 31.Kc2 Kd7 32.Kb3 Bd8 33.a4 Rc5? 33...Rc4 is essential to create counterplay. 34.axb5 Rxb5+ 35.Ka2± a5 36.b4 axb4 37.cxb4 Anand’s endgame technique was extremely instructive, but that falls outside our scope. (1-0, 74) 15.12 AR Saleh Salem 2652 Alexander Areshchenko 2682 Sharjah 2017 (9) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e5 7.Nde2 h5 8.Bg5 Be6 9.Bxf6 Qxf6 10.Nd5 Qd8 11.Qd3 Nd7 12.0-0-0 g6 13.Kb1 Nc5 14.Qa3!? 14...Bxd5 14...Bg7 15.Nec3 b5 16.h4 0-0 exploits the disadvantage of Qa3, that the queen can’t easily support a kingside attack: 17.f3 f5 18.Be2 f4 19.b4 Nd7! (19...Nb7 20.Qb2 Rf7 21.a3²) 20.Qa5 Qxa5 21.bxa5 Kf7 22.Nc7 Rac8 23.Nxe6 Kxe6 24.Nd5 Nc5 The endgame is close to equal, though Black needs to play precisely to prove it after 25.Rhg1! and g2-g4. 15.Rxd5 Bg7 16.Nc3 16.g3!? 0-0 17.Bg2² and Rhd1 is also possible. 16...0-0 16...b5 17.Rd1! 0-0 18.Bd3 Rb8 19.Nd5² 17.h4 b5 18.f3 Rb8 This forces 19.b4, but the subsequent exchange sacrifice is very promising; 18...Qb8 19.Qa5. 19.b4 Ne6 20.Qxa6! Nc7 21.Qc6 Nxd5? 21...Qe7! 22.Rxb5! Nxb5 23.Bxb5 Qa7 24.Nd5 Qf2 25.a4 Qxg2 26.Rf1 is still rough for Black, who must contend with the queenside passers and White’s light-square domination. 22.Nxd5 f5 23.Bxb5 fxe4 24.fxe4± Now Black is positionally lost. 24...Rf7 25.a4 Rc8 26.Qb6 Qf8 27.Qe3 Bh6 28.Qe2 Ra8 29.a5 Kg7 30.Rf1 Raa7 31.a6 Rxf1+ 32.Qxf1 Rf7 33.Qg1 Bd2 34.Bd3 Qd8 35.g3 Kh7 36.Kb2 Kg7 37.Kb3 Kh7 38.c3 Rf3 39.Be2 Rf7 40.b5 Qa5 41.b6 1-0 15.13 Magnus Carlsen 2733 Boris Gelfand 2737 Nice 2008 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e6 7.g4 b5 8.Bg2 Bb7 9.0-0 h6 10.Re1² 10...e5 A) 10...Nbd7?! falls for a common trap: 11.e5! Bxg2 12.exf6 Bb7 13.fxg7 Bxg7 14.Nf5 Bf8 15.Nxd6+ Bxd6 16.Qxd6± Ganguly-Quan, Edmonton 2009; B) 10...Qc7? 11.Nd5! exd5 12.exd5+ Kd8 13.Bd2 b4 14.Bxb4 a5 15.Bd2 Kc8 16.Re3! was a burden for Black in Burden-Lommler, email 2011. 11.Nf5 11.Nde2!? has its logic, angling for 6...e5 7.Nde2 positions: 11...Nbd7 12.Be3 Rc8 13.Qd2² 11...g6 12.Ne3 Nbd7 13.a4 13.Ncd5!? Nxd5 14.Nxd5 Nb6 15.Nxb6 Qxb6 16.Be3 Qc7 17.a4 bxa4 18.Rxa4² 13...b4 14.Ncd5 Nxd5 14...a5 looks decent for Black as White’s knights are in the way of each other. 15.Nxd5 a5 16.c3 16.Be3 Be7 17.Nxe7! Qxe7 18.c3ƒ 16...bxc3 17.bxc3 Be7 Black has to get counterplay before White’s queenside offensive begins: 17...h5! 18.g5 Rc8 19.h4 Be7 20.Ba3 Bxd5 21.Qxd5 Nc5= White’s broken structure annuls his attempts for an edge. 18.Rb1 Bc6?! 18...Bxd5 19.Qxd5 Rc8 19.Bf1 19.Ba3 limits Black’s options by pressuring d6. 19...h5! 20.Bb5 Bxb5 20...Rc8! 21.Bxc6 Rxc6= 21.Rxb5 21.axb5!? 21...hxg4 22.hxg4 Bh4? The bishop is a target here, whereas 22...Nf6 is more solid though White retains an edge. 23.Qf3 23.Kg2! 23...Nf6? 23...Qc8² 24.Rb7+– The rook on the 7th rank is strongest in the middlegame! 24...Qc8 25.g5! Nxd5 26.Qxf7+ Kd8 27.exd5 Qg4+ 28.Kf1 Qh3+ 29.Ke2 Qg4+ 30.Kd3 Qf5+ 31.Qxf5 gxf5 32.Rh1 Kc8 33.Rf7 1-0 15.14 Gerhard Walter 2383 Guntis Gerhards 2323 ICCF email 2009 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e6 7.g4 b5 8.Bg2 Bb7 9.0-0 Qc7 10.Re1 Be7 11.a4 bxa4 12.Rxa4 Nfd7 13.Nd5 exd5 14.Nf5 d4 15.Nxg7+ Kd8 16.Rxd4± Nc6 17.Rd2 Rg8 18.Nf5 Rg6 White has an amazing position, but it is not easy to play these material imbalances in practice. 19.b3 19.f4 takes away squares from Black’s pieces. 19...Bg5 19...a5!? 20.Rde2 Bxc1 21.Qxc1 Qb6 21...Ne7 22.Qb2± 22.Rd1 Kc7 23.Red2 Nde5 23...Rd8 24.Nxd6 Nde5 25.c4 and c4-c5 is good for White, but Black has some resources here. 24.Ne3 Ne7 25.c4 Rc8 26.Qc3 26.Kh1!? 26...h5 27.f4 N5c6? This just loses, so I am unsure why Black didn’t mix it up with 27...hxg4! 28.fxe5 gxh3 29.exd6+ Kb8 30.dxe7 Qc5 31.b4 Qxe7 32.Nf5 Qxe4 33.Qxh3 Rcg8 when Black regains the initiative and will probably eliminate White’s last pawns. 28.f5 Rg5 29.e5! Now it’s curtains. 29...dxe5 29...Nxe5 30.Rxd6 30.c5 Qa7 31.Rd7+ Kb8 32.b4 hxg4 33.h4 Rh5 34.b5 axb5 35.Ra1 Rc7 36.Rxc7 Qxa1+ 37.Qxa1 Kxc7 38.Qa2 Rh7 39.f6 Ng6 40.Bxc6 Bxc6 41.Qa7+ Kc8 42.Nf5 1-0 15.15 Michael Schnabel 2439 Milan Horvat 2456 ICCF email 2013 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 Ng4 7.Bc1 Nf6 8.h3 e6 9.g4 b5 10.Bg2 Bb7 11.0-0 Nfd7 12.a4 b4 13.Na2 a5 14.c3 bxc3 15.Nxc3² Be7 16.Ndb5 Nc5 17.Be3 17.Bf4 e5 18.Be3 0-0 17...Nba6 17...0-0 18.f4 Nc6 19.Rf2 e5 20.Rd2² 18.Qe2 0-0 19.Rad1 The pressure on d6 makes it hard for Black to complete development. 19...Qb8 19...Qb6 20.f4± 20.f4 Bc6 21.b3! 21.g5!? Nxa4 22.f5 with attack. 21...Nb4 22.f5± Re8 23.f6! A nice shot to prosecute White’s advantage. 23...Bxf6 24.Rxf6 gxf6 25.Nxd6 Nd7 26.Nxe8 Qxe8 27.Qf2 Qf8 28.Rd2 Black’s king feels too weak for his game to be tenable. 28...Rc8 29.Ne2 Na6 30.Ng3 Nc7 31.Rc2 Ne8 32.Qd2 Qd6 33.Qxd6 Nxd6 34.Nh5 Kf8 35.Bd2 f5 36.exf5 Bxg2 37.Rxc8+ Nxc8 38.Kxg2 exf5 39.g5 Ne7 40.Bxa5 Nd5 41.Kf3 Ne5+ 42.Kg3 Nd3 43.Nf6 Nxf6 44.gxf6 1-0 15.16 Yelena Dembo 2466 Stanislav Vlcek 2286 Rethymno 2009 (3) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e6 7.g4 b5 8.Bg2 Bb7 9.0-0 b4 10.Nd5 exd5 11.exd5 Be7 12.g5 Nfd7 13.Nc6 Qc7 14.Nxe7 Kxe7 15.Qd4° 15...Kf8 A) 15...Ne5 16.f4 Ng6 17.Re1+ Kf8 18.f5 Ne5 19.Rxe5! dxe5 20.Qxb4+ Ke8 21.d6 Nc6 22.dxc7 Nxb4 23.Bxb7±; B) 15...f6!? 16.Re1+ Kd8 is the option I want to avoid with 13.Nf5: 17.Qh4! Rf8! (17...a5 18.Bf4 Ra6 19.Re6ƒ; 17...h6 18.Bf4 Rg8 19.gxh6 gxh6 20.Bg3²) 18.Qxh7 Ne5 19.Be3 Qf7 The position becomes quite unclear after 20.f4 Qg6 21.Qh4 fxg5 22.fxg5 Nbd7 23.Qxb4 Kc7 as Black has returned some pawns to coordinate his pieces, and White’s king is no less exposed. 16.Bf4 a5 17.Rfe1 Na6 18.Re2 18.a3! is more precise, spreading Black’s defences: 18...Rd8 19.Re2ƒ 18...Qc5?! 18...Qb6! 19.Qxb6 Nxb6 20.Bxd6+ Kg8 21.Rd1 h6 22.Re7 Rd8 23.Bxb4 axb4 24.Rxb7 Na4 gives enough counterplay. 19.Qe4 19.Rd1!? 19...Ne5 20.Bxe5 dxe5 21.Qxe5 h6? A blunder, but even 21...Kg8 22.Rae1 Rf8 23.Qe7 Qxe7 24.Rxe7 Bc8 25.d6 Nb8 26.Bd5² is passive. 22.Rae1+– 22.g6! 22...Nc7 23.g6 fxg6 24.Qf4+ Kg8 25.Re7 1-0 15.17 Albert Serazeev 2482 Frederic Mignon 2460 ICCF email 2013 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e6 7.g4 d5 8.exd5 Nxd5 9.Nde2 Bb4 10.Bg2 0-0 11.0-0 Nxc3 12.Nxc3 Qc7 13.Qd4 Bd6 14.Be3 Bd7 15.Rad1 Bh2+ 16.Kh1 Be5 17.Qb6 Bc6 18.Qxc7 Bxc7 19.Ne4 Nd7 20.Nc5 Ne5 21.f4 Bxg2+ 22.Kxg2 Nc4 23.Bc1 b6 24.Rd7 Rfc8 25.b3 Nd6 26.Nd3 b5 27.Bb2 Bb8 28.Bd4² a5 Black wants to activate his a8-rook, but he’s not in time. 29.c3 Kf8 30.f5! exf5 31.Re1! fxg4 Trading by 31...Re8 is a typical method of defence, but 32.Bb6 fxg4 33.Rxe8+ Nxe8 34.Rd8 gxh3+ 35.Kxh3 Ke7 36.Ne5 Bxe5 37.Rxa8 Bxc3 38.Bxa5² retains winning chances, as knights are notoriously bad against a passed rook’s pawn. 32.hxg4 Re8 33.Rf1 Re2+ 34.Kf3 Re8 35.Rh1 Ne4 36.Rh5 Ra6 37.Rf5 Kg8 38.Rxb5 Rh6 39.Be5 Nf6 40.Rd4 Ba7 41.Rd6 Bb8 42.Rxb8 Rxb8 43.Nf4± I haven’t found substantial improvements over Black’s play, yet he ends up in a lost position. 43...Nxg4 44.Kxg4 Rxd6 45.Bxd6 Rd8 46.Bc7 Rd2 47.a4 f6 48.Bxa5 Kf7 49.b4 g5 50.Nh5 Kg6 51.b5 f5+ 52.Kf3 Kxh5 53.b6 g4+ 54.Kf4 Rf2+ 55.Kg3 Rb2 56.Bb4 1-0 56...Kg5 57.Be7+ Kg6 58.a5 h5 59.Kf4+– 15.18 Evgeny Lobanov 2273 Roman Sekretaryov 2344 ICCF email 2010 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e6 7.g4 d5 8.exd5 Nxd5 9.Nde2 Bb4 10.Bg2 0-0 11.0-0 Nxc3 12.Nxc3 Qc7 13.Qd4 Nc6 14.Bxc6 Bxc3 15.Qxc3 Qxc6 16.Qxc6 bxc6 17.f4² Black tends to hold the draw in correspondence games, but over-the-board his task is much more unpleasant. 17...f5?! 17...a5 18.Be3 Ba6 19.Rf2 Rfd8 20.b3 (20.a4!?² is probably the best winning try, minimising exchanges) 20...Rd5 21.Rd2 Rad8 22.Rad1 f6 (22...Be2 23.Rxd5 Rxd5 24.Rd2 Rxd2 25.Bxd2 Bd1 26.Bxa5 Bxc2 27.Kf2²) 23.Kf2 a4 24.Ke1 axb3 25.cxb3 e5 26.fxe5 fxe5= Black was safe by now in Daubenfeld-Michalek, email 2013. 18.g5 Re8 19.b3 e5 20.fxe5 Rxe5 21.Bf4 Rd5 22.Rad1ƒ Black hasn’t solved the problem of his c8-bishop, and is poorly placed to stop White’s plans. 22...Ra7 22...a5 23.a4! 23.Rxd5 cxd5 24.Rd1 Rd7 25.Kf2 Kf7 26.Kg3 Kg6 27.h4 Bb7 28.Be5 Kf7 28...Kh5!? may be a better try. 29.Kf4 g6 30.Ke3 Re7 31.Kd4± Re8 32.Rh1 Rc8 33.Rh2 Re8 34.a3 Re7 35.Rh3 Re8 35...Re6 36.Rc3 Rc6 37.Rc5 Ke7 38.c3 Rxc5 39.Kxc5 is a winning endgame, because Black can’t move his bishop properly and Kb6/a2-a4/b2-b4-b5 is coming in some order. 36.Rc3 Re7 37.a4 Re6 38.Rc7+ Re7 39.c3+– Ke6 40.Rxe7+ Kxe7 41.Kc5 d4 42.Kb6 Be4 43.c4 Bc2 44.b4 1-0 15.19 José Americo Paiva Moreira 2399 Jorge Silva Lopes 2068 ICCF email 2011 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e6 7.g4 d5 8.exd5 Nxd5 9.Nde2 Bb4 10.Bg2 0-0 11.0-0 Nxc3 12.Nxc3 Qc7 13.Qd4 Nc6 14.Bxc6 Bxc3 15.Qxc3 bxc6 16.b3² As with the previous game, White is playing for two results. 16.Be3 e5 17.Rae1² is more common, but I found 17...e4!?N to be slightly frustrating, as Black can play for ...f7-f5 in many lines. 16...Rd8 16...Bb7 17.Ba3 Rfd8 18.Rad1² keeps Black’s bishop hemmed in. 17.Ba3 17.Re1 c5! 17...f6 18.Rad1 Bb7 19.Qc4 Qf7 20.Qe2! e5 21.c4 Qc7 22.Bc5 Even with a computer to help, it’s not so easy to draw, due to White’s far superior bishop. 22...a5?! 22...Qa5!? 23.b4 Qc7 24.a3² looks strange, but at least 24...a5 opens a file for counterplay. 23.a4! h6 24.Kg2 Re8 25.Qe3ƒ Qf7 25...Bc8 26.f4! 26.Rg1 Bc8 27.Kh2 h5? Black gets sick of waiting, but destroys his own king safety. 27...Bd7 28.Rd6 Re6 was necessary. 28.g5± fxg5 29.Rxg5 Bf5 30.Rdg1 g6 31.Rxh5 Rad8 32.Qh6 Qg7 33.Qxg7+ Kxg7 34.Rxf5 1-0 15.20 Soren Rud Ottesen 2386 Brian Feldborg 2211 ICCF email 2011 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.h3 e6 7.Be3 Be7 8.g4 0-0 9.g5 Nd7 10.h4 a6 11.f4ƒ Qb6 Black should try and disrupt White’s attack in some way: 11...Re8 12.Qf3 Nxd4 13.Bxd4 b5 14.0-0-0 b4 15.e5! Rb8 16.Ne4 Bb7 17.exd6 Bxd6 18.Qe3 Bxe4 19.Qxe4± 12.a3! A typical way of defending b2 (...Qxb2 loses the queen to Na4). 12...Nxd4 13.Bxd4 Qc6 13...Qa5 14.Qf3 e5 15.Be3 exf4 16.Qxf4± resembles the game. 14.Qd2 e5 15.Nd5 Bd8 16.fxe5 Nxe5 17.0-0-0± These structures are fantastic for White if Black can’t immediately threaten the white king. 17...Be6 18.Kb1 a5 19.h5 b5 20.Bxe5 dxe5 21.h6 g6 22.Qh2 Bxd5 22...f6 23.gxf6 Bxd5 24.exd5 Qd6 25.Bxb5+– 23.Qxe5 Bxe4 The fastest way out of the suffering. 24.Qg7# 15.21 Erik Blomqvist 2567 Grzegorz Nasuta 2448 London 2016 (4) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e6 7.g4 Nfd7 8.g5 b5 9.a3 Bb7 10.h4 Nc6 11.Be3 Rc8 12.Nxc6 Rxc6 13.Qd4 Ne5 14.0-0-0 Nc4 15.Rh3² The basis of my recommendation is to recapture on e3 with the rook, maximising our central coordination. 15...Qc7 16.Bd2 Nxd2 17.Rxd2 Qb6 18.Qd3?! White keeps the queen for an attack, but I prefer 18.a4!? Qxd4 19.Rxd4 bxa4 20.Rb4! Rc7 21.Rxa4² when Black’s a6pawn is hard to save. 18...g6 18...Be7 19.f4 0-0 is okay for Black, as a later g5-g6 will allow ...Bf6. 19.e5!? Rc7? Black gets too fancy; he should lock down with 19...d5! 20.Ne4 h5 21.Nf6+ Kd8 as it’s not easy for White to find a break. 20.exd6 Rd7 21.Nxb5! 21.Ne4 Bxe4 22.Qxe4 Rxd6 23.Qa8+ Qd8 24.Qxa6! Rxd2 25.Bxb5+ Ke7 26.Bd3 Rxc2+ 27.Bxc2± 21...axb5 22.Qxb5 Qxb5 23.Bxb5 Kd8 24.Bxd7 Kxd7 25.Rb3 Bc6 26.Rb8 Bg7 27.Rxh8 Bxh8 28.c4 Be5 29.b4!+– It’s Space Invaders with White’s four passed pawns! 29...Bf4 30.b5 Be4 31.c5 Bd5 32.a4 h6 33.a5 hxg5 34.hxg5 Bxg5 35.a6 Bxd2+ 36.Kxd2 Ba8 37.Kc3 g5 38.Kb4 g4 39.b6 Kc6 40.b7 Bxb7 41.axb7 Kxb7 42.Kb5 f5 43.c6+ Kc8 44.Kb6 f4 45.c7 Kd7 46.Kb7 1-0 15.22 Sergey Evtushenko 2509 Mark Noble 2552 ICCF email 2012 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e6 7.g4 Be7 7...Nfd7 8.g5 b5 9.a3 Bb7 10.h4 (10.Be3 gives Black the extra option of 10...Nb6! 11.h4 N8d7, though 12.h5!?N could be explored more deeply, e.g. 12...d5 13.Rh3 e5 14.exd5 exd4 15.Qxd4 Bd6 16.h6 Be5 17.hxg7 Bxd4 18.Bxd4 Rg8 19.Re3+ Qe7 20.Rxe7+ Kxe7 21.Bg2 Nc4 22.0-0-0 with very interesting compensation for the rook, possibly even enough for an advantage) 10...Be7 11.Be3 Nb6 12.Qd2 N8d7 13.0-0-0 is our move order. 8.g5 Nfd7 9.Be3 b5 10.a3 Bb7 11.Qd2 Nb6 This variation is so unfashionable I’d almost forgotten about it! 12.0-0-0 N8d7 13.h4 Rc8 14.h5 Ne5 15.Qe1! Anticipating ...Nc4. 15...Qc7 15...Nbc4? 16.f4±; 15...Nec4? 16.g6!± 16.Rh3! Nec4 17.g6! White’s attack strikes first, and Black’s position becomes extremely difficult to defend. 17...Bf6?! The normal move, but radical measures were already required. 17...Nxb2!? 18.h6! fxg6 19.Ncxb5 leads to insane complications: 19...Qc5 (or 19...axb5 20.hxg7 Rg8 21.Bxb5+ Nd7 22.Kxb2ƒ) 20.hxg7 Rg8 21.Kxb2 axb5 22.Bxb5+! Kf7 23.Rf3+ Bf6 24.c4! Bxe4 25.Bg5 Nxc4+ 26.Ka2 Ra8 (26...Qxg5 27.Qxe4) 27.a4 Qxg5 28.Qxe4 d5 29.Qxe6+ Kxg7 30.Nf5+ Kh8 31.Nh6 Qxh6 32.Qxf6+ Qg7 33.Rxd5 Rgb8! 34.Rc5!? (34.Qxg7+ Kxg7 35.Rf4 Nb6 36.Rd6 Nc4! is a beautiful trick that narrowly maintains the balance) 34...Qxf6 35.Rxf6 Nb6 36.Ka3² 18.gxf7+ Kxf7 18...Qxf7 19.h6 g6 20.Kb1 0-0 21.Rf3 is an unpleasant pin down the f-file: 21...Nxb2?! (21...Rc5?! 22.Bh3 Bc8 23.e5! Rxe5 24.Nc6ƒ won the exchange for insufficient compensation in Podgursky-Canizares Cuadra, LSS email 2010; 21...Nxe3 22.fxe3 Nc4² may be the best try) 22.Rxf6! Qxf6 23.Kxb2 Rxc3 24.Kxc3 Bxe4 25.Kb3 Rc8 26.Ka2 Bd5+ 27.Kb1 Na4 28.Rd3 Bc4 29.Rd2± White’s king was secure in Ermolaev-Sukhorskij, email 2012, and he won shortly. 19.Bxc4 Nxc4 20.Rf3! Like before, the absolute pin neutralising Black’s attacking attempts while furthering White’s play. 20...h6 A) 20...Ne5?! 21.Rg3 Nc4 22.h6 g6 23.Rf3 Ke7 24.Qg1 Nxe3 25.Rxf6! Kxf6 26.fxe3 Kf7 27.Rf1+ 1-0 FilipchenkoKleiser, email 2014, was not a great defensive example; B) 20...Rhg8 21.Qg1 Qe7 22.Bg5 Rc5 23.h6 Ne5 was Rudenko-Nemchenko, email 2012, and now 24.Rf4!N 24...Ng6 25.Bxf6 gxf6 26.Rg4 retains a strong initiative. 21.Qg1 Qe7 22.Qg2± The engine doesn’t see it, but White’s attack plays itself. 22...Ke8 Trying to flee to the queenside. 22...Kg8 23.Rg1 Rh7 traps in Black’s rook, and after 24.Qh3 Re8 25.Rg6 Kh8 26.Kb1 Bc8 27.Rfxf6! gxf6 28.Bc1 Black couldn’t resist White’s pressure forever in Evans-Hybl, email 2013. 23.Qh3! Nxe3 24.fxe3 Rc4 24...Kd7? 25.Nd5+– 25.Rdf1 Bc8 26.Qg2 Rf8 27.Kb1 Qc7 28.Qg6+ Qf7 29.Qg3 Kd7 30.Qg4 Kd8 31.R3f2 Qd7 32.Rd1 Rc5 After some manoeuvring, White makes his push. 33.e5! Rxe5 34.Ne4 Kc7 If 34...Bb7 35.Nxd6!. 35.Rdf1 Qe7 36.Qg6 Qe8 36...Qf7 37.Qh7! is still strong, though perhaps less so than in the game. 37.Qh7 Rf7 38.Nxf6 gxf6 39.Qxh6 Qe7 40.Qg6 Rg7 41.Qd3 Rxh5 42.Rxf6+– Black has stopped the h-pawn, but his king is too exposed for this mostly major-piece position. 42...Kb6 43.Rf8 Qc7 44.b4 Rgh7 45.R1f6 R5h6 46.Rxh6 Rxh6 47.e4 Rh7 48.Qe3 Kb7 49.e5 Qg7 50.Rf6 1-0 15.23 Kaido Külaots 2581 Danny Raznikov 2489 Riga 2013 (9) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e6 7.g4 Be7 8.g5 Nfd7 9.h4 b5 10.a3 Bb7 11.Be3 Nc6 12.Qd2 Nde5?! An empty move. 12...Qc7 13.Nxc6!? Bxc6 14.h5ƒ 13.Nxc6 Bxc6 14.0-0-0± 0-0?! Castling into the attack, but the engine’s 14...Ng4 15.Bf4 Ne5 16.Bg3 makes me chuckle. 15.f4 Nc4 16.Bxc4 bxc4 17.h5 White’s attack runs like clockwork. 17...f5 18.h6 g6 19.Qd4 Rf7 20.exf5 exf5 21.Nd5 Bxd5 22.Qxd5 Rc8 23.Bd4 Qd7 24.Bc3 Qa7 25.Rhe1 Qc5 26.Qe6 1-0 15.24 Ian Nepomniachtchi 2703 Alexander Grischuk 2752 Russia tt 2016 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e6 7.g4 Be7 8.g5 Nfd7 9.Be3 b5 10.a3 Bb7 11.h4 Nc6 12.Qd2 Rc8 13.Nxc6 Rxc6 14.0-0-0 0-0 15.Kb1 Ne5 16.Rh3 Nc4 17.Qe1 Nxe3 18.Rxe3² Qc8 The planned ...Be7-d8-a5 is too slow. A) 18...f6 is too weakening after 19.Bh3 Bc8 20.e5 fxe5 21.Rxe5 dxe5 22.Rxd8 Bxd8 23.Qxe5±; B) 18...Rc5! 19.f4 Qb6 however prepares ...a6-a5/...b5-b4, and allows Black to gradually equalise: 20.Qg3 (20.Qd2 Rfc8 21.f5 Re5 is unclear; 20.Bh3 a5 21.f5 Re5 22.f6 Bd8=) 20...a5 21.h5 (21.f5 Rfc8 22.e5 Rxe5 23.Rxe5 dxe5 24.fxe6 b4 25.exf7+ Kf8 26.axb4 axb4 27.Nd5 Bxd5 28.Rxd5 Qa7 gives Black a nice attack with ...Ra8) 21...Bc6 22.Nd5 exd5 23.exd5 Rxd5 24.Rxd5 Bxd5 25.Rxe7 b4 26.Qe3 Qxe3 27.Rxe3 g6 Black is holding, though White can continue to set small problems with 28.h6! f6 29.Bh3. 19.f4 Bd8 19...Rc5 is now too slow after 20.Qg3 Kh8 21.Be2ƒ. 20.f5! Ba5 21.b4 21.Bh3!? Bxc3 22.bxc3 e5 23.f6 Qc7 24.h5± 21...Bb6 22.Red3 exf5 22...Kh8 23.Qd2 Qc7 24.Bh3 Bd4 25.Rxd4 Rxc3 26.Rd3± 23.exf5 Re8 24.Qd2 Rc4 25.g6?! White has a lot of tempting options, but this feels rushed. 25.h5! Qxf5 26.Rxd6 Rc6 27.Rd3! Qe5 28.Nd5±; 25.f6!? 25...hxg6?! 25...fxg6 26.fxg6 Rxh4 27.Bg2 Bxg2 28.Qxg2 hxg6 29.Qxg6 Qe6 30.Rxd6 Qxg6 31.Rxg6 Bd4 keeps Black active enough to draw. 26.fxg6 fxg6 The players were short of time, but Nepomniachtchi (nicknamed ‘Nepo’ by the chess media) handles the rest of the game with aplomb. 27.Nd5!? 27.Bh3! Qc7 28.Re1 Rxe1+ 29.Qxe1± 27...Bxd5 27...Bd8 28.Bh3 Qa8 29.Qg2 Bxd5 30.Rxd5± was better. 28.Rxd5 Rxh4 28...Be3 29.Bxc4 Bxd2 30.Rc5+ bxc4 31.Rxc8 Rxc8 32.Rxd2+– 29.Rxd6 Be3 30.Qd5+ Kh8 31.Bd3 Opposite-coloured bishops endgames are often winning for the side with the initiative. 31...Bd4 32.Rh1 Qh3 33.Rd1 Qg3 33...Rf8 34.Rxa6 Qg4 35.Re1+– 34.Bxg6! Qc3 35.Qxd4! Stylish! 35...Rxd4 36.R6xd4 Rf8 37.Rh4+ Kg8 38.Rdh1 1-0 15.25 Sergei Movsesian 2580 Vladimir Akopian 2620 Yerevan ch-ARM 1996 (10) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 e6 7.g4 h6 8.f4 Nc6 9.h3 Qc7 10.Qe2 Be7 11.Bg2 Nxd4 12.Bxd4 e5 13.Be3± exf4 A) 13...b5 14.g5 hxg5 15.fxg5 Nh5 16.Nd5±; B) 13...Be6 14.0-0-0 Rc8 (14...Bc4 15.Qf2 exf4 16.Bxf4 0-0 17.g5 hxg5 18.Bxg5±) 14.Bxf4 Be6 15.0-0-0 White’s extra space poises him well for a kingside attack, but e4-e5 breaks can also be strong. 15...0-0 15...Nd7 16.Nd5 Bxd5 17.exd5 Ne5 18.h4!? Ng6 19.Bg3 0-0 20.Kb1± 16.e5 dxe5 17.Qxe5 Qc8 17...Qxe5 18.Bxe5 Nd7 19.Bd6!? Bxd6 20.Rxd6 Ra7 21.Ne2± exerts heavy piece pressure on Black. 18.g5 18.Rhf1 Rd8 19.a3± 18...hxg5 19.Bxg5 Nd7 19...Rd8 was better. 20.Qg3 Bxg5+ 21.Qxg5 f6 Black had to play 21...Qd8, though of course this gives up a pawn. 22.Qh4 Rf7 23.Rhg1 23.Nd5! 23...Nf8 24.Nd5+– Once White gets the g-file attack going, it’s hard to stop him. 24...Bf5 25.Qf2 Rb8 26.Nb6 Qc7 27.Qxf5 Qxb6 28.Bd5 Qe3+ 29.Kb1 Re8 30.Bxf7+ Kxf7 31.Qd5+ 1-0 15.26 Alexei Shirov 2726 Boris Gelfand 2691 Monaco rapid 1999 (8) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 e6 7.g4 h6 8.Bg2 Nc6 9.h3 Ne5 10.Qe2 Qc7 11.0-0-0 Bd7 12.f4 Nc4 13.Kb1 e5 14.Nb3 Rc8 15.Rd3 b5 16.g5 hxg5 17.fxg5 Nh5 18.Nd5 Qb7± 19.Bc1 19.g6!? is perhaps what Shirov would have played in a classical game. 19...Be6 20.Qe1! Be7 20...Qc6!? 21.Bf3!± Bd8 22.Bg4 a5 23.Qd1 23.g6! forces the kingside open. 23...g6 24.Rf1 a4 25.Nd2 Bxg5? Gelfand cracks under the pressure of Shirov’s superlative play. 25...Bxd5 26.Bxc8 Qxc8 27.exd5 Bxg5 was a necessary exchange sacrifice, though 28.Nxc4 bxc4 29.Ra3 Bxc1 30.Qxc1± still looks close to winning for White. 26.Bxe6 fxe6 27.Nxc4 bxc4 28.Qg4! A fantastic way to conclude proceedings. 28...exd5 29.Rxd5 Qd7 30.Qxg5 Qe6 31.Bd2 Rb8 32.Bc3 Rf8 33.Rfd1 Qf6 34.Qd2 Ng3 35.Qe3 Qf4 36.Qa7 Rd8 37.Bxe5 Qxe4 38.Bxg3 Qxd5 39.Qe3+ 1-0 I think most players would be happy to play such a quality game in classical! 15.27 Ryszard Skrobek 2621 Stefan Ciesielski 2574 ICCF email 2006 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 e6 7.g4 h6 8.Bg2 Nc6 9.h3 Qc7 10.f4 Na5 11.Qe2 Nc4 12.0-0-0 Bd7 13.Kb1 Rc8 14.Bc1± b5 A) 14...Be7 can be met as in the game: 15.b3 Qa5 (15...Ne5 16.fxe5 dxe5 17.Nxe6 fxe6 18.Rd3ƒ is similar) 16.Rd3 Ne5 17.fxe5 dxe5 18.Nxe6 fxe6 (18...Bxe6 19.Nd5!) 19.Nd1± and I don’t see Black’s compensation for his passive position; B) 14...e5 15.Nf5 Na3+ 16.Ka1 has scored 5/5 in correspondence/freestyle games, as Black lacks a way to increase the pressure: 16...b5 (16...g6 17.fxe5 dxe5 18.Ne3 Bg7 19.Rd2± was Trail Blazer-Fredis cpu, Freestyle 2006) 17.Qd3! b4 18.bxa3 Qxc3+ 19.Qxc3 Rxc3 20.Nxd6+ Bxd6 21.Rxd6 Rxc2 22.Rg1² White developed his endgame initiative nicely in Rheinstädtler-Scheer, email 2012. 15.b3! 15.Rhe1± is more common and also good, but 15.b3 is a complete refutation. 15...Ne5 15...Qa5 16.bxc4 Qxc3 17.e5! dxe5 18.fxe5 Nh7 19.cxb5 axb5 looks slightly scary from a human perspective, but 20.Nb3! Qc4 21.Qf2± is objectively very strong for White, as Black can’t exploit White’s weaknesses without full development; 15...Nb6 16.e5! Qxc3 17.exf6 gxf6 18.Bb7 Rb8 19.Bxa6+– is similarly effective. 16.fxe5 dxe5 17.Ndxb5 axb5 18.Nxb5 Qb8 19.a4+– White is up a pawn – it feels like two with Black’s crippled kingside majority! 19...Bc6 20.Bb2 Be7 21.h4 Bxb5 22.axb5 Nd7 23.c4 Qc7 24.Rh3 24.Qd2 is a better way to support the g4-g5 break. 24...Ra8 25.g5 hxg5 26.hxg5 Rxh3 27.Bxh3 Qa7 28.Kc2 g6 29.Qd2 Rd8 30.Bg4 Nf6 31.Qh2 Rxd1 32.Bxd1 Nxe4 33.Bf3 Qe3 34.Qe2 Qxe2+ 35.Bxe2 Nxg5 36.Bxe5 f6 37.Bf4 Ne4 38.Bf3 Nd6 39.Be3 e5 40.c5 Nf5 41.Bf2 Nd4+ 42.Bxd4 exd4 43.b4 Bd8 44.b6 Kd7 45.Kd3 Kc8 46.Kxd4 f5 47.Bd5 Kb8 48.Ke5... 1-0 (53) 15.28 Viswanathan Anand 2804 Maxime Vachier-Lagrave 2723 Stavanger 2015 (6) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 e6 7.g4 h6 8.Bg2 Nc6 9.Be3 Be7 10.f4 Nd7 11.0-0 Nxd4 12.Qxd4 0-0 13.Qd2 Rb8 14.Ne2 b5 15.Rad1 This game has been analysed in many places, so I’ll focus on the theoretical component. 15...Qc7 15...Bb7 16.Ng3 Qc7 17.f5 Nf6 transposes to the game. 16.f5 16...Nf6 16...Ne5?! 17.b3 Kh7 18.Nf4 Rd8 19.Nh5² 17.Ng3 17.fxe6 Bxe6 18.Nd4 Nd7= 17...Bb7 17...Re8 gives an extra option of 18.Kh1!? (18.c3 exf5 19.Nxf5 Bxf5 20.Rxf5 Nd7 21.e5! Nb6 22.Bd5 Nxd5 23.Qxd5 Bf8 24.Rdf1 Rxe5 25.Rxf7 Rxd5 26.Rxc7 Rd3 27.Rf3 Re8 28.Kf2 Be7 29.Ra7 Rd1 30.Rxa6 Rb1=) 18...b4 19.Bf4 Rb5 20.Bxd6 Bxd6 21.Qxd6 when Black can’t claim full equality yet with a pawn deficit. 18.Kh1 White had a draw in hand with 18.Bxh6 gxh6 19.Qxh6 d5 20.Kh2 Bd6 21.Qg5+=. 18...Rbd8? One improving move is enough to lose in such a sharp position. 18...Kh7! looks obvious, to stop Bxh6, but one should also see the ...Rh8/...Kg8 manoeuvre against g4-g5: 19.c3!? (19.g5 hxg5 20.Bxg5 Rh8! 21.fxe6 fxe6 22.Qd3 Kg8 – White has absolutely nothing here) 19...Rbd8 20.Qe2 d5 21.Qf2 dxe4 22.Bb6 Qe5 23.Bxd8 Rxd8 24.Rxd8 Bxd8° Black has full compensation and White should settle for 25.fxe6 fxe6 26.Qf4 Qxf4 27.Rxf4 Kg6! and one of various ways to keep the 0.00 evaluation. 19.Bxh6! gxh6 20.Qxh6+– d5 20...Rfe8 21.fxe6 fxe6 22.Qg6+ Kh8 23.Nh5+– 21.g5! Qxg3 22.Rd3 Black loses the queen or gets mated. 22...Nh5 If 22...Nxe4 23.f6 Bxf6 24.Bxe4 dxe4 25.Rxg3 e3+ 26.Kg1 Bg7 27.Qh5 the two bishops offer some swindling chances, but White should win. 23.g6 fxg6 24.fxg6 Rxf1+ 25.Bxf1 Nf6 26.Rxg3 dxe4 27.Be2 e3+ 28.Kg1 Bc5 29.Kf1 1-0 It’s not for nothing that Anand is called the champion of 6.h3 ! Chapter 16 The 6.Be2 Najdorf 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 It’s healthy to have back-up options in a repertoire, and while 6.h3 is the most critical try at the time of writing, we saw that it doesn’t give an advantage by force. Therefore, I want to offer a solid, low-maintenance back-up line that still poses some practical questions. 6.Be2!? We haven’t been playing Be2 in the other variations, but I have some original interpretations in mind that will lead to positions resembling the rest of our repertoire. Black doesn’t touch the e-pawn A) 6...Qc7 This is a bit slow and might be countered with 7.g4!? h6 8.f4N 8...e5 9.Nb3 b5 10.a3 exf4 11.Bxf4²; B) If 6...b5? 7.a4 b4 8.Nd5 is much more potent than after 6.h3 b5: 8...Bb7 (8...Nxe4? 9.Bf3 f5 10.Qe2+–) 9.Nxf6+ gxf6 10.0-0! Black was clearly worse in Ganguly-Nakamura, Internet 2006, as 10...Bxe4 11.Re1 d5 12.Bf3 Bxf3? 13.Qxf3 leaves White too far ahead in development; C) 6...Nc6 7.Be3 is likely to transpose to 6...e6 after 7...e6. Instead 7...e5 8.Nb3 is an improved version of the 6.Be2 e5 7.Nb3 variation as Black has misplaced his knight on c6. This is expertly exploited in our model game TseshkovskyStaniszewski, Lubniewice 1995; D) 6...Nbd7 7.Be3 is again likely to transpose after 7...e6. Instead, 7...Nc5 (7...Qc7 8.a3!?N 8...e6 9.g4 h6 10.Qd2 b5 11.f3 Bb7 transposes to 6...e6) 8.f3 e6 9.Qd2² leaves the c5-knight looking misplaced; E) 6...g6 7.Be3 Bg7 8.Qd2... ... is a good Dragon for White as Be2 is a bit more useful than ...a7-a6: E1) 8...h5?! prevents 9.Bh6, but 9.0-0-0 Nbd7 10.f4!± is a strong alternative set-up; E2) 8...Ng4? 9.Bxg4 Bxg4 10.Bh6 0-0 11.f3 Bd7 12.h4 is already a very strong attack; E3) I once played 8...b5? only to find that 9.Bf3! with the threat of 10.e5 sets insurmountable problems to Black; E4) 8...0-0 9.0-0-0 Nc6 10.Kb1 Bd7 (or 10...Ng4 11.Bxg4 Bxg4 12.f3 Bd7 13.h4 h5 14.g4!+–) 11.f3 Rc8 12.g4 b5 13.h4 Ne5 14.h5 and White’s attack is already too fast, see Solak-Annaberdiyev, Turkey tt 2015; E5) 8...Nc6 9.0-0-0 and now: E51) 9...Nxd4 10.Bxd4 gives White the opportunity to charge the kingside pawns to good effect: 10...0-0 (10...Be6 11.g4!ƒ) 11.h4! h5 12.f3 b5 13.g4!±; E52) 9...Ng4 10.Bxg4 Bxg4 11.f3 Bd7 (11...Be6 12.Nd5 Bxd5 13.exd5 Ne5 14.b3² kept Black’s counterplay in tow in Lu-Wan, Moscow 2011) 12.Nxc6 bxc6 13.Bh6N 13...0-0 14.h4² White is effectively a tempo up on the Be2/Be3/Qd2 Dragon main line, as ...a7-a6 was completely useless; E6) 8...Nbd7 9.f3 h5 (9...b5 can be met thematically: 10.a4 b4 11.Na2 a5 12.c3 bxc3 13.Nxc3 Bb7 14.0-0 0-0 15.Nb3 Ne5 16.Rfd1 Nc6 17.Rac1± with durable queenside pressure, thanks to the strong b5 outpost) 10.0-0! Black has stopped our kingside attack, so we can switch to the Classical system, where ...Nbd7/...h7-h5 is out of place: 10...0-0 (10...Qc7 11.a4 b6 12.Nd5 Nxd5 13.exd5± is a similar bind, Palladino-Sanna, email 2009) 11.a4 Ne5 12.Nd5± Black was in a pickle in Glaser-Banyushkin, email 2010 (or 12.a5). Carlsen’s blitz twist 6...e5 is the most popular move, preventing White’s aggressive plans. A) 7.Nb3 Be7 8.Be3 Be6 9.Qd3 0-0 10.0-0 used to entice me. It was neutralised by 10...Nbd7 11.Nd5 Bxd5 12.exd5 Ne8! 13.a4 Bg5 14.a5 Bxe3 (14...g6) 15.Qxe3 Nef6 16.c4 Rb8 as played in Carlsen-Vachier-Lagrave, Karlsruhe 2017. But we can improve for White: 17.Rfb1 Qc7 (17...b6 18.axb6 Qxb6 19.Na5²) 18.Nd2 b6 19.axb6 Rxb6 20.Nb3 Nc5 21.Nxc5 dxc5 and now the prophylactic 22.Bd1!±; B) Carlsen recently played 7.Nf3!? in a few quickplay games, and it makes sense – compared to the Boleslavsky, Black has played ...a7-a6 instead of the developing ...Nc6, although on the other hand the knight is not very good on c6 with the d6/e5 structure. Let’s have a look: A) 7...Be6?! 8.Ng5 picks up the bishop pair; B) 7...Qc7 8.Nd2!?N 8...Be6 9.Nf1 g6 10.h4 h5 11.Ne3 Be7 12.0-0 0-0 13.a4 is slightly better for White, who has a strong clutch of d5, while Black can’t easily find a pawn break; C) 7...h6 is a natural move, but White’s idea is not limited to Bc1-g5xf6: 8.Nd2 C1) 8...b5?! 9.a4 b4 10.Nd5 Nxd5 11.exd5² and a5/Nc4 is a highly promising structure for White; C2) 8...Be6 9.Nc4 b5 10.Ne3 Nbd7 11.0-0 Be7 12.a4N 12...b4 13.Ncd5 a5 14.Nxf6+ Nxf6 15.Bb5+ Nd7 16.c3 bxc3 17.bxc3 0-0 18.Ba3² depicts the positional edge White is striving for; C3) 8...Be7 9.Nc4 b5 10.Ne3 0-0 11.0-0 Nbd7 12.a4 b4 13.Ncd5 Nxd5 14.Nxd5 a5 15.Re1 Nf6 16.Bc4² White’s control over d5 gives him a modest pull. D) 7...Be7 8.Bg5 and now: D1) After 8...Be6 9.Bxf6 Bxf6 the play resembles our 6.h3 repertoire, though admittedly the 6.h3 version is a bit more critical: 10.Qd2 (10.0-0 0-0 11.Nd5 Nd7 12.Bc4 Rc8 13.Bb3 Nc5 is also completely fine for Black) 10...0-0 (10...Nc6 11.Nd5! Bxd5 12.Qxd5 0-0 13.0-0 Qc7 14.c3 gave White a small, risk-free edge in our model game Hovhannisyan-Ter Sahakyan, Skopje 2017) 11.0-0 Qc7 12.Rfd1N 12...Be7 13.Nd5 Bxd5 14.Qxd5 Nd7 15.Nd2! b5 16.c4 b4 17.Nf1 Nc5 18.Ne3 – the position is equal and rather safe for both sides; D2) 8...Nbd7 is aimed against Bxf6/Nd5: 9.a4 D21) 9...b6 10.Nd2! is better for White – see Carlsen-Vachier-Lagrave, Paris rapid 2017; D22) 9...Qb6!?N is the computer’s preference, disrupting White’s plan. If 10.Qc1 (10.a5!? Qxb2 11.Bd2 Qb4 gives sufficient compensation, but not more than that) 10...h6 11.Be3 Qc6 12.Nd2 Nc5 13.Bf3 Be6 14.0-0 0-0 15.a5 Rac8 16.Re1 Rfd8 17.h3 and there’s not a lot either side can do from this position; D23) 9...0-0 10.Nd2 D231) 10...Nc5 11.Bxf6 Bxf6 12.Nc4 Be7 13.a5 Rb8 14.Nb6 Be6 15.0-0 Nd7 16.Ncd5 Nxb6 17.Nxb6² is White’s positional desire; D232) 10...h6 11.Bh4 d5 12.exd5 Nxd5 13.Nxd5!N 13...Bxh4 14.Nc4 Nc5 15.a5 Rb8 16.Ncb6 Be6 17.Bc4 is better for White due to his strong knights; D233) 10...d5!? 11.exd5 Nxd5 12.Nxd5N (12.Bxe7 Nxe7 13.Nde4 Nc6 14.0-0 f5 15.Nd6 Kh8! 16.Bc4 Qe7 17.Qd5 Nb6 18.Nf7+ Kg8 19.Nh6+ Kh8 20.Nf7+ is a draw by repetition, which is not a bad ‘worst case’ for the repertoire) 12...Bxg5 13.Ne4 Nf6! (without this trick, Black might find himself under pressure) 14.Nexf6+ Bxf6 15.0-0 e4! (15...Be6 16.Bf3 Be7 17.Re1 Bd6 18.a5 and Nb6 could give White a tiny bit of pressure in an otherwise equal position) 16.Nxf6+ Qxf6 17.c3 Be6 18.Qc1 Rad8 This position is completely equal, though we saw Black had to find several accurate moves along the way. The Be2 Scheveningen – introduction 6...e6 7.Be3! I believe in White’s chances for an advantage if he plays in the English Attack spirit with f2-f4 and/or g2-g4 against most replies: A) 7...b5?! 8.Bf3! forces Black to play 8...e5 to stop White’s 9.e5 threat: 8...e5 9.Nf5 g6 (9...d5? 10.Bg5 Bxf5 11.exf5 places Black’s centre under insurmountable pressure, as 11...e4? fails to 12.Nxd5! Qxd5 13.Qxd5 Nxd5 14.Bxe4+– as in Frolyanov-Nagimov, Nabereznye Chelny 2010) 10.Nh6! It is difficult for Black to complete his development because of the h6-knight: 10...Bb7 (or 10...Be6 11.Qd2 Nbd7 12.0-0 Qc7 13.a3ƒ) 11.0-0N 11...Nbd7 12.Re1²; B) 7...Nbd7 8.a4!? (8.g4 was my initial intention, but Black can hit back against White’s pawn storm with 8...h6 9.f4 g5!?=) 8...b6 9.f3 Bb7 10.Qd2² Black finds it difficult to get active, while White can choose between a kingside pawn storm and kingside castling, depending on Black’s reply. See the game Robson-Gerasimov, email 2013, for details; C) 7...Nc6 8.f4 is likely to transpose to another line. An exception is 8...Bd7 9.Bf3!? Rc8 (9...Qc7?! 10.Nb3! Be7 11.g4 h6 12.h4 gives White a massive attack) 10.Qe2 b5 11.a3 Qc7 12.g4! Nxd4 13.Bxd4 with an initiative for White, see Svidler-Rublevsky, Poikovsky 2003; D) 7...Qc7 is the trendiest, but this move is not very useful if White switches back to an English Attack: 8.Qd2! b5 (8...Be7 9.g4! b5 10.g5 Nfd7 11.a3 Bb7 12.0-0-0 resembles our 6.h3 Najdorf, but where we have Be2 in place of h2-h3. See Rosche-Raijmaekers, email 2013) 9.f3! More often White stops ...b5-b4 with a2-a3, but this is not yet necessary: D1) 9...Bb7 10.a4! b4 11.Na2 shows an advantage of not playing a2-a3: 11...d5 12.e5! Nfd7 13.f4 a5 Now White might even grab the initiative with 14.f5!N 14...exf5 15.e6 Nf6 16.0-0±; D2) 9...Be7 10.g4 Bb7 (10...Nc6 11.Nxc6 Qxc6 is just bad for Black because of 12.a4! b4 13.Na2 Qxa4 14.Qxb4 Qxb4+ 15.Nxb4, winning a pawn) 11.a3 (now we are fine with playing a2-a3, as Black is committed to ...Be7 and his queenside counterplay is therefore slower) 11...Nc6 (11...Nfd7 12.0-0-0 0-0 13.g5 Nb6 14.h4² is too slow for Black, see Rosche-Dietrich, email 2013) 12.0-0-0 0-0 (12...Ne5 13.h4 Nc4 14.Bxc4 bxc4 15.Kb1 Rb8 16.Ka1 Ba8 17.Rb1± was the familiar perfect structure for White in Overton-Gerola, email 2011) 13.g5 Nd7 14.h4 (the play is pretty similar to the previous chapter) 14...Nce5 (14...b4 15.axb4 Nxb4 16.h5 Nc5 17.Kb1 Rac8 18.g6! Qa5 19.h6! was a crushing breakthrough in Acedanski-Hoffmann, email 2007) 15.f4 Nc4 16.Bxc4 Qxc4 17.f5! We’ve transposed to Rosche-Dietrich; D3) 9...Nbd7 10.g4! White has an improved English Attack in all lines, as Be2 is more useful than ...Qc7: D31) 10...Nb6 11.a4!N 11...b4 12.Na2 d5 13.a5 Nc4 14.Bxc4 dxc4 15.Nxb4² doesn’t give Black enough for a pawn; D32) 10...b4 11.Na4 h6 12.c3 Nc5 13.Nxc5 dxc5 14.Nc2 a5 15.Bf4N 15...Qb7 16.h4! Bd7 17.Ne3 and eventually g4g5 will give White a strong offensive; D33) 10...h6 11.a3 Bb7 12.0-0-0 d5 13.exd5 Nxd5 14.Nxd5 Bxd5 15.Bf4 Qb7 (15...Qb6 16.Rhe1²) 16.Nf5N 16...f6 17.h4! (Black is not fully prepared for an open confrontation) 17...Nc5 (17...Rc8 18.Kb1 Nc5 19.Bd6! exf5 20.Bxf8 Rxf8 21.Qxd5 Qxd5 22.Rxd5 fxg4 23.fxg4 offers some pressure in the endgame, with a bishop vs. knight advantage) 18.Bd6! Rd8 19.Bxf8 Kxf8 20.Qc3 Qb6 21.Ne3 Black has yet to parry White’s initiative. 7...Be7 without fast castling 7...Be7 8.f4 Suffice to say that we’re not playing this version of 6.Be2 positionally! You’ll also find the 8.Qd2 move order discussed in the games section. A) 8...Qc7 9.g4! forces Black’s hand if he wants to avoid a serious disadvantage. A1) 9...h6 10.Bf3 looks good for White (Vovk-Ardelean, Vaujany 2013); A2) 9...Nc6? 10.g5 Nd7 11.Rf1! b5 12.Nxc6 Qxc6 13.Qd4 0-0 14.0-0-0 Rb8 15.f5 placed heavy pressure on Black in Kanmazalp-Grachev, Moscow 2015; A3) In several games Black stumbled into 9...b5 10.g5 Nfd7 11.a3 Nc6 (11...Bb7 12.Rf1 Nc5 13.f5!±; 11...Nb6 12.f5!N 12...e5 13.Nb3 is depressing for Black) 12.Nxc6 Qxc6 13.Qd4! 0-0 14.0-0-0, which reminds a lot of our 6.h3 repertoire! 14...Bb7 15.f5 Rfc8 16.Rhf1 and White is ready to play f5-f6 and rip open Black’s king; A4) 9...d5!? 10.exd5 (the quieter 10.e5 Ne4 11.Nxe4 dxe4 12.c3N 12...Nc6 13.Nxc6 Qxc6 14.Qd4 also seems a bit better for White) 10...Nxd5 11.Nxd5 exd5 12.Qd2!N 12...Bh4+ 13.Bf2 Bxf2+ 14.Kxf2 (the king is surprisingly well guarded on f2) 14...0-0 15.Bf3 Nd7 16.Rhe1 Nc5 17.Kg1 Ne4 18.Bxe4 dxe4 19.f5 Qe5 20.c3 White has a tiny pull with his strong knight and a weakness on e4 to target. B) 8...Nc6 9.Qd2! These positions can often arise via a Taimanov move order (though not with our 7.Qf3 Taimanov repertoire). We can claim an improved version as in principle, Black shouldn’t play ...Nc6 in reply to early f2-f4 set-ups (...b7b5/...Bb7/...Nbd7 is more harmonious). B1) 9...Bd7 10.0-0-0 b5 11.Bf3 Rc8 12.g4ƒ is difficult for Black to play, see Gomila Marti-Monreal Godina, email 2010; B2) 9...Qc7 10.0-0-0 0-0 (10...Bd7 11.g4 Nxd4 12.Qxd4 e5 13.Qd3 is fantastic for White, as 13...Bxg4 14.Bxg4 Nxg4 proves a poisoned pawn after 15.Nd5 Qc6 16.Rhg1 h5 17.h3 Nxe3 18.Qxe3± Velimirovic-Rajkovic, Majdanpek 1976. Black can’t handle the pressure down the d- and g-files) 11.g4! and now: B21) 11...d5 12.exd5 Nxd5 13.Nxd5 exd5 14.Bf3 Rd8 15.Kb1 is a prospectless position for Black. If 15...Na5 16.b3!N kills the knight; B22) 11...b5 12.g5 Nd7 13.Nxc6 Qxc6 14.a3 leaves Black without much hope of survival, practically speaking. For instance, 14...Nc5 15.Rhf1N 15...Bb7 16.f5! already feels winning with best play; B23) 11...Nxd4 12.Qxd4 e5 (12...b5 13.g5 Nd7 14.h4! (14.f5!? has scored nearly 100% for White, see Szabo-Flumbort, Budapest 2014) 14...Bb7 15.h5N 15...Nc5 16.Bf3 f6 17.h6 g6 18.Rhf1² White’s spatial advantage is not going anywhere) 13.Qd3 Bxg4 (after 13...exf4 14.Bxf4 Be6 15.g5 Nd7 16.Bxd6 Bxd6 17.Qxd6 Qa5 18.h4 Rac8 19.Qd4 Nb6 20.a3± White was a pawn up with the better position in Nijboer-Van Kooten, Groningen 2008) 14.Bxg4 Nxg4 (this again looks almost suicidal, opening the g-file in front of the black king) 15.Nd5 Qd8 (15...Qd7?! 16.f5!± as in ShirovLjubojevic, Monaco blind 1999, hardly requires analysis) 16.Bb6 Qe8 17.Rhg1 Nf6 18.fxe5 Nxd5 19.exd5 dxe5 Black can try to cling on to life, but after the pointed 20.Qf5!N (ruling out a ...Qd7 blockade) 20...g6 21.d6 Bd8 22.Be3 Qe6 23.Qxe6 fxe6 24.d7 his position does not inspire confidence, to say the least; B3) 9...0-0 10.0-0-0 Black has a lot of alternatives to ...Qc7, but his play remains slower in all cases: B31) 10...e5... ... hasn’t been popular as White can claim a stable endgame advantage with 11.Nxc6 bxc6 12.fxe5 dxe5 13.Qxd8 Rxd8 14.Rxd8+ Bxd8 15.Bf3N 15...Be6 16.Na4 due to Black’s isolated queenside pawns; B32) 10...Bd7 11.g4 Nxd4 12.Qxd4 Bc6 13.g5 Nd7 14.h4 scores very heavily for White, and might even be close to winning with best play: 14...b5 (slow play will get Black killed after 14...Re8 15.h5 Rc8 16.Rhg1 followed by g5-g6) 15.h5 e5 16.Qd2 We see how to exploit White’s massive advantage in Jakubowski-Cerveny, Czechia tt 2009; B33) 10...Nxd4 11.Qxd4 b5 is asking for too much: 12.e5 dxe5 13.Qxd8 Bxd8 14.Bf3 Rb8 15.fxe5 Nd7 16.Ba7 Bc7 17.Bxb8 Bxb8 18.Ne4N 18...Nxe5 19.Nc5² doesn’t give Black enough for the exchange; B34) 10...Nd7 11.g4 Nxd4 12.Qxd4 b5 13.g5 Now this is what we call an English Attack on fire! B341) 13...Rb8 14.a3 Qa5 (Black wants to play 15...b4, but White has everything under control; 14...Qb6 15.Qxb6 Nxb6 16.h4ƒ was a joyless ending for Black in Efimenko-Sokolov, Plovdiv 2008) 15.Qb4 Qxb4 (15...Qd8 16.Rxd6! Qc7 17.Rhd1 Bxd6 18.Qxd6 Qxd6 19.Rxd6 is a neat exchange sacrifice for domination: 19...Rd8 20.e5±) 16.axb4 Bb7 17.Rhf1² The exchange of queens hasn’t ceased White’s pressure at all; B342) 13...Bb7 14.Rhg1N 14...Qc7 (14...Bc6 15.h4 Rb8 16.h5 b4 17.Nd5! exd5 18.h6± is just too fast) 15.f5 This can lead to a truly stunning variation: 15...d5! 16.fxe6 Bc5 17.g6!! Bxd4 18.gxf7+ Kh8 19.Bxd4 Ne5 20.exd5 Rad8 21.Rde1 Ng6 22.Bd3 Bxd5 23.Nxd5 Rxd5 24.e7 Qf4+ 25.Kb1 Qxf7 26.exf8=Q+ Qxf8 27.Rgf1 Qd8 28.c3 and even now the bishops and rooks beat the queen, rook and knight! The correct 8...0-0 8...0-0 9.g4! There’s no reason to let Black get away with quiet play. 9...d5! Black must counter in the centre if he wants to avoid a hack. A) The non-critical developing line 9...Nc6 10.g5 Nd7 11.h4 Re8 12.Qd2 Nxd4 13.Bxd4 b5 14.a3 Bb7 15.0-0-0 Rc8 16.Rhe1N 16...Nc5 17.Bf1ƒ is a familiar scenario to us; B) 9...b5 10.g5 Nfd7 11.a3 Bb7 12.Rg1 may be even scarier than the 6.h3 version of the attack, due to the rapid f4-f5: 12...Nc5 (12...Nc6 13.f5! Nxd4 14.Bxd4N 14...Bxg5 15.Bxg7! Kxg7 16.h4ƒ is strong too) 13.f5 Kh8 Kasparov once reached this position against Short, and was fortunate White didn’t play 14.Rg4!N 14...Nbd7 15.Qd2, which looks incredibly strong. The point is 15...Ne5 16.Rh4± when it’s hard to get out of b2-b4 and fxe6. 10.e5 Nfd7 11.g5! An important move to stop a disruptive ...Bh4. With only one low-level game in the database, we have a fertile ground for investigations, but I think White’s kingside attack is much more dangerous than the engines believe. The latest word is the correspondence game Hall-Tleptsok, email 2016, which is still in progress at the time of writing: 11.0-0 Nc6 12.Qd2 Qc7 13.Bf3 Nxd4 14.Bxd4 b5 15.Rac1 Bb7 16.g5 b4 17.Ne2 Rac8 18.Qe3 Nb8 19.Bg4 Nc6 20.f5 exf5 21.Bxf5 Qd8 22.Bxc8 Bxg5 23.Nf4 Bxc8 24.Bb6 Qd7 and Black has full compensation for the exchange. 11...Nc6 11...Qc7 12.0-0!² is a funny transposition to a Classical Scheveningen line, covered in Gburek-Cerrato, email 2012. 12.h4 A) 12.0-0 seems less apt here due to 12...Bc5!=; B) 12.a3!? Qc7 13.h4 b5 14.Bf3 Nb6 15.Nce2 Nc4 16.Bc1 Nxd4 17.Nxd4 Bd7 18.c3² and Qd3 might be the most promising direction for White, but tests are required. 12...Nxd4 12...Qc7 13.Qd2 b5 14.Nxc6 Qxc6 15.Bf3 Nb6 16.b3 Bb4 17.Bd4 Bb7 18.a3 Be7 19.h5² is the sort of bind Black would rather avoid. 13.Bxd4 b5 14.a3 b4 The laborious 14...Nb8 15.Bf2 Nc6 16.Rh3 looks better for White. 15.axb4 Bxb4 Stockfish calls this 0.00 at depth 51 (!), but I think every human would prefer to be White after... 16.h5 a5 17.0-0 Ba6 18.Na4 Bxe2 19.Qxe2 ... because of the kingside space and Black’s isolated a5-pawn. Summary 2...d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be2: 6...Nc6 – +0.25 6...g6 – +0.45 6...e5 7.Nf3: 7...h6 – +0.20 7...Be7 – 0.00 6...e6 7.Be3: 7...Nbd7 – +0.25 7...Qc7 – +0.30 7...Be7 8.f4 followed by g2-g4 – +0.15 16.1 Vitaly Tseshkovsky 2540 Piotr Staniszewski 2405 Poland tt 1995 (9) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 Nc6 7.Be2 e5 8.Nb3² 8...Be6 8...Be7 9.0-0 0-0 10.f3 b5 (10...a5 11.Na4! (after 11.Bb5 Na7 12.Bd3 Nc6 I’m not convinced our bishop is better on d3 than e2) 11...Be6 12.Nb6 Rb8 13.Bb5 Na7 14.Qe2 Nxb5 15.Qxb5² wins the a5-pawn) 11.Qd2 Black’s position is very undesirable, e.g. 11...Bd7 (11...Bb7 12.Nd5!±) 12.a4 b4 13.Nd5 Nxd5 14.exd5 Na5 15.Qxb4 Nxb3 16.Qxb3 Rb8 17.Qc3± 9.0-0 9.Nd5 Bxd5 10.exd5 Ne7 11.c4 g6= 9...Be7 9...Rc8!? According to my chess understanding, Black should not be able to equalise in this way, but this move order is very robust: 10.Qd2 Be7 11.Bf3!? (11.f3 d5 12.exd5 Nxd5 13.Nxd5 Qxd5 14.Qxd5 Bxd5 15.Rfd1 Be6 16.c3 f6 17.Nc5 Bxc5 18.Bxc5 Ne7 19.Bf2 Kf7 is only a symbolic endgame pull for White) 11...Na5 12.Nxa5 Qxa5 13.a3 h6 14.Rfc1 Qc7 15.Nd5 Bxd5 16.exd5 0-0 17.c4 White has the easier game because of his bishop pair, but it’s too early to speak of a sure advantage. 10.Nd5 Bxd5 10...0-0 11.f3 Bxd5 12.exd5 leaves Black without a great square for his knight: 12...Nb4 (12...Na5 13.c4 Nxb3 14.Qxb3 Qc7 15.Bb6 Qc8 16.Bf2²; 12...Nb8 13.Qd2 Nbd7 14.Na5!? Qc7 15.c4² intends b2-b4/Nb3 to unite White’s pawns) 13.c4 a5 14.Qd2 b6 15.Nc1 Na6 16.Bd3 Nd7 17.Bf5² Black is passive and can’t hope to hold back White’s queenside advance forever. 11.exd5 Nb8 12.a4!? 12.c4 0-0 12...a5?! Black is trying to hold up White’s majority, but actually makes it easier for White to open the queenside. 12...Nbd7 13.a5 0-0 14.c4ƒ 13.Bb5+! Nbd7 14.Nd2! 0-0 14...Nxd5 loses material after 15.Nc4 Nxe3 16.fxe3 0-0 17.Bxd7 Qxd7 18.Nb6 Qe6 19.Nxa8 Rxa8 20.Qf3± 15.Nc4 Qc7 16.c3± e4 17.b4!? 17.Bd4 17...axb4 The computer recommends giving up the a5-pawn and playing 17...Ne5. 18.cxb4 Ne5 19.Nb6+– Black’s pieces run out of room. 19...Rfd8 20.Rc1 Qb8 21.Bd4 g6 22.Qc2 Ne8 23.Qxe4 f5 24.Qc2 f4 25.Bxe5 dxe5 26.Nd7 Rxd7 27.Bxd7 Bxb4 28.Qb3 Qd6 29.Be6+ Kh8 30.Rc4 Bc5 31.Qxb7 Nc7 32.Rfc1 Nxe6 33.dxe6 Ba3 34.Rc7 1-0 16.2 Dragan Solak 2622 Babageldi Annaberdiyev 2234 Turkey tt 2015 (9) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 5...a6 6.Be2 g6 7.Be3 Bg7 8.Qd2 0-0 9.0-0-0 Nc6 10.Kb1 Bd7 11.f3 Rc8 12.g4 Ne5 would be our move order. 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 0-0 8.Qd2 Nc6 9.g4 9.0-0-0 9...Bd7 10.0-0-0 Ne5 11.Kb1 Rc8 12.Be2 a6 13.h4 b5 14.h5+– Black has won a few games at the amateur level, so it’s worth seeing how to bring home the attack. 14...b4 A) If 14...Re8 15.Nd5 is a typical resource to trade Black’s defenders: 15...e6 16.Nxf6+ Bxf6 17.f4 Nc4 18.Bxc4 bxc4 19.hxg6 fxg6 20.e5!+–; B) 14...e6 15.a3 Rb8 16.Bh6 Bxh6 17.Qxh6 Qe7 18.g5 Nxh5 19.Rxh5! Black gave up the piece in Ginzburg-Hoffman, Villa Gesell 1998, as 19...gxh5 20.Nf5 exf5 21.Nd5 nabs the queen instead! 15.Nd5 e6 15...Nxd5 16.exd5 a5 17.Bh6+– 16.Nxf6+ Bxf6 17.g5 Bg7 18.Qxb4 Good enough to win, but I would smell blood with 18.f4! Nc4 19.Bxc4 Rxc4 20.Qh2 and the h-file attack is deadly. 18...Qc7 19.Qd2 Rb8 20.Nb3+– Rfc8 21.Bd4 a5 22.hxg6 fxg6 23.f4 a4 24.fxe5 axb3 25.cxb3 dxe5 26.Bc3 Bc6 27.Qe3 Qb7 28.Rh4 Rd8 29.Rdh1 Rd4 30.Bxd4 exd4 31.Qh3 Bxe4+ 32.Rxe4 Qxe4+ 33.Bd3 Qe5 34.Qxh7+ Kf8 35.Qxg6... 1-0 (41) 16.3 Robert Hovhannisyan 2619 Samvel Ter Sahakyan 2581 Skopje 2017 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be2 e5 7.Nf3 Be7 8.Bg5 Be6 9.Bxf6 Bxf6 10.Qd2 Nc6 11.Nd5 Bxd5 12.Qxd5 0-0 13.0-0 Qc7 14.c3² Rfd8 15.Rfd1 Rac8 15...Ne7 16.Qb3 Rab8 17.a4² 16.Ne1 This knight manoeuvre is too slow, and White should prefer 16.g3! g6 17.h4² for ideas of h4-h5/Kg2. 16...g6 17.g3 h5 18.Ng2 18.Nc2 is a more flexible square. 18...Bg5 19.Rd3 Ne7 20.Qb3 Qc6 20...Kg7 21.Bf3 b5 22.Rad1 22.h4 Bh6 23.Ne3 Bxe3 24.Rxe3 a5 The engine gives a tiny edge for White, but we know from the Sveshnikov chapter that such positions are harmless. 22...Qb6 23.h4 Bh6 24.Ne3 Bxe3 25.Rxe3 Kg7= Black even slightly outplayed White from here, but the outcome was nonetheless peaceful: ½-½ (45) 16.4 Magnus Carlsen 2832 Maxime Vachier-Lagrave 2796 Paris rapid 2017 (3) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be2 e5 7.Nf3 Be7 8.Bg5 Nbd7 9.a4 b6 10.Nd2² 10...h6 A) 10...0-0 11.Nc4 Qc7 12.0-0 Bb7 13.Ne3ƒ was the start of a model game: 13...Rfe8 (13...Bd8 14.Bf3) 14.Bc4 Rac8 15.Bxf6 Nxf6 16.Qd3± Ra8?! (16...a5) 17.Rfd1 Red8 18.Bd5 Rac8 19.Ra3! I particularly like this rook lift, to attack the b6 weakness. 19...Rd7 20.Rb3 Bd8 21.Bc4 Ra8 22.Ncd5 Nxd5 23.Bxd5 Bxd5 24.Qxd5 Rc8 25.Rc3 Qb8 26.Rxc8 Qxc8 27.Nc4 h6 28.Nxe5 Rc7 29.Qxd6 Bf6 30.c3 Bxe5 31.Qxe5 Rd7 32.Rd5 b5 33.Qf5 1-0 Eswaran-Abrahamyan, St Louis 2016; B) 10...Bb7 11.Nc4 Qc7 12.Ne3 h6 13.Bxf6 Nxf6 14.Bc4 0-0 15.Bd5ƒ 11.Bxf6 11.Bh4 Bb7 12.Nc4 seems better, heading for the same set-up as in the 10...0-0 note: 12...Qc7 (12...g5?! 13.Bg3 Nxe4 14.Nxe4 Bxe4 15.f3 Bg6 16.Nxd6+ Bxd6 17.Qxd6± leaves Black’s king without a haven) 13.Ne3 0-0 14.0-0 Bd8 15.Bf3² and White can train his forces on the d-file. 11...Nxf6 12.Nc4 Bb7 13.a5 13.Qd3 13...b5 14.Nb6 Nxe4!? Black heads for complications; simpler was 14...Rb8 15.0-0 0-0 16.Qd3 Qc7 17.Rfd1 Qc5 18.g3 g6= when the b6knight is less effectual than it looks. 15.Nxe4 Bxe4 16.Bf3 16.c4!² was more dynamic. 16...Bxf3 17.Qxf3 Ra7 18.c4 d5! 19.cxb5 Bb4+ 20.Ke2 Bxa5 21.Nxd5 axb5 22.b4 Bb6 23.Rxa7 Bxa7 24.Ra1 Bb8 25.Qd3 0-0 26.Qxb5 e4= Black has sufficient counterplay, although 26...Qh4! 27.h3 Bd6 would place the onus on White to maintain the balance. 27.g3 Be5?! 27...Qg5= 28.Rd1 Qg5 29.Kf1 f5 30.Qe2 Setting up a crafty cheapo! 30...Kh8? 30...Bb8!² avoids tactical problems by keeping the pieces defended. 31.f4!+– exf3 32.Qxe5 Qh5 33.Nf4 Qxh2 34.Ng6+ Kh7 35.Nxf8+ Kh8 36.Ng6+ Kh7 37.Nh4 Qh1+ 38.Kf2 Qxd1 39.Qxf5+ 1-0 16.5 Nigel Robson 2596 Vladimir Gerasimov 2479 ICCF email 2013 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 e6 7.Be2 Nbd7 8.a4 b6 9.f3 Bb7 10.Qd2² Such a set-up would have been deemed inconsistent in the pre-computer era, but it’s hard for Black to strike out. 10...h5!? Black wants a share of the rook’s pawn play! A) 10...d5?! 11.exd5 Nxd5 12.Nxd5 Bxd5 13.0-0 Bb7 14.Rfd1±; B) 10...Be7 is too simplistic after 11.g4! 0-0 12.g5 Ne8 13.h4 Nc7 14.h5 and the attack rages on; C) 10...Rc8 11.g4 Ne5 12.0-0-0! Qc7 13.Kb1 Be7 14.h4 h5 15.g5 Nfd7 16.Rhg1ƒ Shapiro-Gulevich, email 2011; D) 10...Qc7 11.0-0-0 Ne5 12.g4 Nc4 13.Bxc4 Qxc4 takes a bit too long after 14.g5 Nd7 15.h4 Be7 16.Nb3 Nc5 17.Nxc5 bxc5 18.h5ƒ. 11.0-0-0 There are as yet no examples, but the correct plan may be 11.0-0. 11...Nc5 A) 11...Qc7 12.g3! is a useful preparation for h2-h3 and g2-g4: 12...Ne5 13.Kb1 Rd8 (13...Be7 14.h3 (14.Bg5!?) 14...d5 15.exd5 Nxd5 16.Nxd5 Bxd5 17.Bf4² keeps Black restrained in the centre) 14.Bg5 Be7 15.Rhf1 Nc4 16.Bxc4 Qxc4 17.h3ƒ Black couldn’t resolve his king position in Goncharov-Sammut, email 2012; B) 11...Be7 12.Kb1 Rc8 13.Nb3 0-0 (13...Qc7 14.h3 h4 15.Rhe1 Nh5 16.Bg5ƒ) 14.h3 d5 15.exd5 Nxd5 16.Nxd5 exd5 17.Nd4 Re8 18.g4± 12.Kb1 Be7 13.Rhg1 Qc7 I suppose Black wanted to keep his rook on a8 for a future ...b7-b5 sacrifice, but it never amounts to anything. Better was 13...Rc8 14.Nb3 (14.h3 h4 15.Nb3 Kf8!?) 14...Nxb3 (14...0-0 15.Nxc5 bxc5 16.g4! hxg4 17.Bh6!!± is a beautiful computer line you can explore for yourself) 15.cxb3 0-0 16.Bd4 b5! (Black shouldn’t just wait for h2-h3 and g2-g4-g5) 17.axb5 axb5 18.Bxb5 Qc7 19.Rc1 Qa5 20.Ba4 (White successfully blocks all the queenside files) 20...Rfd8 21.Rc2 Qa6 22.Bb5 Qa8 23.Bb6 Rf8 24.Qd3 White is better, but Black should be able to keep the focus away from his king. 14.Bf2 14.g3!? and h2-h3 is logical too. 14...Rc8 15.Qe3 g6 15...Qd7 is harder to crack, e.g. 16.Nb3 d5 17.e5 Ng8. 16.h4 At first, I was unsure of this move, but fixing Black’s structure makes a lot of sense. 16...Ncd7 17.Rd2 Kf8 18.g4 hxg4 19.fxg4 Nc5 20.Bf3 e5 21.Nb3 Nfd7 22.g5! 22.h5 b5! gives Black a lot of counterplay. 22...b5 23.Bg4 This is the key difference, pinning Black down. 23...Nxa4 24.Nd5 Bxd5 25.exd5 Nab6 26.Qd3± White dominates the kingside and centre, and went on to win an impressive game. 26...Kg7 27.Re2 Rcf8 28.h5 Bd8 29.h6+ Kh7 30.Bxd7 Nxd7 31.Nd2 Be7 32.Be3 Kg8 33.Rf2 Rh7 34.Rgf1 Kh8 35.b3 Qb7 36.Ne4 a5 37.c3 Qb8 38.Rb2 Qb7 39.c4 b4 40.Ra2 Qa8 41.Kb2 Qd8 42.Rg1 Rg8 43.Rga1 f5 44.gxf6 Nxf6 45.Ng5 Nxd5 46.Nxh7 Nxe3 47.Qxe3 Kxh7 48.Rxa5 Rf8 49.Ra7 Rf7 50.Rd1 Qb8 51.Rd2 Kg8 52.Rf2 Qf8 53.h7+ Kxh7 54.Rxf7+ Qxf7 55.c5 Black resigned. 16.6 Peter Svidler 2713 Sergei Rublevsky 2670 Poikovsky 2003 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be2 d6 7.Be3 Nf6 8.f4 Bd7 9.Bf3 Rc8 10.Qe2 b5 11.a3 Qc7 12.g4 Nxd4 13.Bxd4² Qc4?! 13...e5 14.Be3 Qc4 15.Qxc4 Rxc4 16.g5ƒ 14.Qxc4 Rxc4 15.0-0-0± Black can’t yet develop his king’s bishop because of 16.g5. 15...h6 15...e5 16.fxe5 dxe5 17.Bxe5 Nxg4 18.Bd4± 16.Rhe1 Be7 17.e5! Even in Open Sicilian endgames, White should play aggressively. 17...dxe5 18.Bxe5 Bc8 Black wants to castle, but he pays a hefty price with this undeveloping move. 18...a5!? 19.Be2 19.Rd3 was better. 19...Rc6 20.h4 0-0 21.g5 Nd7 22.Bd4 hxg5 23.hxg5 Bd6 23...Rc7 24.Bh5!?ƒ with g5-g6 in mind is still unpleasant for Black. 24.Be3 Bxa3 25.Nxb5 Bxb2+ 26.Kxb2 axb5 27.Bxb5 Rc7 28.c4 Nc5 29.f5 This move bamboozles Black in the game, but White can also build up with 29.Bd4!?. 29...exf5? 29...Bb7 30.fxe6 fxe6 31.Ka3± The bishop pair and passed c-pawn give excellent winning chances in the endgame. 30.Bf4 Rb7 31.Bd6 Be6 32.Bxc5 Rc8 33.Rxe6! fxe6 34.g6!+– Rbb8 35.Ba7 Rb7 36.Bf2 Kf8 37.Kb3 e5 38.Rd6 f4 39.Rd5 Rc6 40.Bc5+ 1-0 16.7 Ernst Rosche 2499 Kees Raijmaekers 2427 Remote email 2013 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 e6 7.Be2 Be7 7...Qc7 8.Qd2 Be7 would be our move order. 8.Qd2!? I had initially rejected this move, but a real case can be made that Be2 is more useful than f2-f3 for supporting g4-g5; 8.f4 8...Qc7 8...0-0 9.0-0-0 (9.g4 b5 10.g5 b4!) 9...b5! 10.Bf3 leads to a semi-forced line: 10...b4 11.Nce2 Bb7 12.e5 Nd5 13.exd6 Qxd6 14.Nf5 Qc7 Black has been drawing all the high-level correspondence games, but I like the 15.Bxd5 Bxd5 16.Bb6 Qb7 17.Nxe7+ Qxe7 18.Nf4 Bc4 19.Qe3 Nd7 20.Ba5!?² of Chukanov-Kovalev, email 2012, as Black’s queenside structure is fixed. Note that 20...Bxa2?! 21.b3 Qf6 22.Rhe1 Qa1+ 23.Kd2 Qf6 24.Ke2! incarcerates the a2-bishop. 9.g4! b5 10.g5 Nfd7 11.a3 Bb7 12.0-0-0 Nc6 12...Nc5 13.f3 Nbd7 14.Kb1 0-0 15.h4 Ne5 16.h5 Rab8 17.g6± was a model attacking display in Forcen EstebanKorneev, La Roda 2017. 13.h4! White shouldn’t trade knights as that would help Black play ...Rb8 and ...b5-b4 and open the queenside: 13.Nxc6 Bxc6 14.h4 Rb8 15.h5 a5 16.Qd4 0-0 17.Nd5 exd5 18.exd5 Rfc8 19.h6 Ne5 20.dxc6 Qxc6 21.Bd3 Nxd3+ 22.Qxd3 g6 23.f4 b4 24.Rh2 bxa3 25.Qxa3 Rb4= is an indicative variation. 13...b4 14.axb4 Nxb4 15.f3 Curiously, the b4-knight and b7-bishop get in the way of Black’s queenside attack. 15.Kb1 Nc5 16.f3 Rb8 17.h5 0-0 18.Bf4! (I found this improvement just before the book went to the printers. 18.g6 Bf6 19.Rdg1 Ba8 feels easier for Black to play) 18...e5 19.Nf5 exf4 20.Qd4 Ne6 21.Nxe7+ Qxe7 22.Qxb4 Qxg5 23.h6! g6 24.Rxd6² White has control. 15...Rc8?! 15...d5 was necessary to fight for the initiative: 16.Bf4 (16.h5 Nc5 17.g6 0-0-0!; 16.exd5 Bxd5 17.Bf4 Qa5 18.Nb3 Na2+; 16.Kb1 dxe4 17.h5 Nc5 18.f4 0-0-0 19.Bc4 Kb8 20.Qe2° gives good compensation, but not more) 16...e5 17.Bg3 Qb6 (17...Bc5! 18.Nb3 d4 19.Kb1 Rc8 20.Na2 Nxa2 21.Kxa2 Bb6 and Black’s strong centre balances the play) 18.Nf5 d4 19.Kb1 Rc8 20.Bf2 Rg8 21.Nxd4 exd4 22.Bxd4 Qd6 23.Qe3 White had excellent compensation in Rogos-Capak, email 2008, due to Black’s king being stuck in the centre. 16.Kb1 Nc5 17.Ncb5! Qa5 18.Na3± Black’s pieces are in a logjam. 18...Qa4 18...0-0 19.h5 with attack. 19.h5 Bxe4 20.Rh4! In these lines, the initiative is often more important than material. 20.fxe4 Nxe4 21.Qc1 Nc3+ 22.bxc3 Rxc3 23.Qb2 Rxa3= 20...e5 21.fxe4 exd4 22.Qxd4 Ne6 23.Qd2 0-0 24.c3 Nc6 25.Nc4 Rb8 26.Qc2 Qxc2+ 27.Kxc2± White has the bishop pair, more space and better structure, so it’s not shocking that he went on to win. 27...h6 28.Rg4 Bxg5 29.Rxd6 Rfc8 30.Bxg5 Nxg5 31.b4 Rc7 32.e5 Rf8 33.Rg1 Rfc8 34.Rgd1 Ne4 35.Kb3 Kf8 36.R6d5 Na7 37.R1d4 f5 38.e6 Ng3 39.Rd2 Ke7 40.Rd7+ Rxd7 41.exd7 Rd8 42.Nb6 Ne4 43.Rd1 1-0 16.8 Ernst Rosche 2484 Udo Dietrich 2426 Remote email 2013 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 e6 7.Be2 Be7 8.Qd2 8.g4!? b5 9.g5 Nfd7 10.a3 Bxg5 11.Qd2 Bf6 12.0-0-0 Bb7 13.Rhg1° as played in Olofsson-Ljubicic, email 2013, seems balanced to me, but you might like to explore more deeply as this is by no means an easy position for Black to defend. 8.f4 is the other option. 8...0-0 9.0-0-0 Qc7 10.g4 b5 11.a3 Bb7 12.f3 Nfd7 13.g5 Nb6 14.h4² Nc6 Black must get the pieces out. A) 14...d5 15.g6!; B) 14...Nc4? 15.Bxc4 Qxc4 16.h5± 15.g6! Such sacrifices are as natural as a baby’s smile. 15...hxg6?! 15...Nxd4 16.gxh7+ Kh8 17.Bxd4 (17.Qxd4 Nc4 18.Bxc4 Qxc4= forces the queens off) 17...e5 18.Bxb6 Qxb6 19.Kb1 is still worse for Black. 16.h5 Nxd4 17.Bxd4 g5 18.h6! Once the h-file is open, Black’s days are numbered. 18...e5 19.hxg7 Kxg7 20.Rdg1 Rg8 21.Be3 Kf8 22.Bxg5 Ke8 23.f4 Qc5 24.Rd1 Bxg5 25.fxg5 Na4 26.Rh3 Nxc3 27.Rxc3 Qb6 28.Bh5 Bxe4 29.Rf1 Rg7 30.Bf3 Bxf3 31.Rcxf3 e4 32.Rf6 Rc8 33.Qf4 1-0 16.9 Andrey Vovk 2567 George Ardelean 2505 Vaujany 2013 (4) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 e6 7.Be2 Qc7 8.g4 h6 9.f4 Be7 10.Bf3² Nc6 10...g5!? is the engine’s advice, but 11.f5² is like what we’ve seen in the 6.h3 chapter. 11.Qe2 Nxd4 After 11...e5 12.Nxc6 bxc6 13.h4 d5 14.exd5 Nxd5 15.Nxd5 cxd5 16.Bxd5 Rb8 17.0-0-0± Black regretted delaying castling in Voveris-Altieri, email 2014. 12.Bxd4 e5 13.Be3 exf4 13...Be6 14.0-0-0 Rc8 15.Kb1 exf4 16.Bxf4± is a familiar structure to us. 14.Bxf4 Be6 15.0-0-0 Nd7 16.Nd5 Bxd5 17.exd5 Kd8?! There’s no way the king belongs in the centre! 17...Ne5 18.Bxe5 dxe5 19.Kb1ƒ was better. 18.h4± Bf6 19.g5 Be5 20.Be3 hxg5 21.Bxg5+ We should welcome the opening of files: 21.hxg5! 21...Nf6?! 21...f6 was better. 22.h5 Rc8 23.Rd3 Qc4 24.Kb1 Rc7? 24...Qb5± 25.Qg2 25.Qf2 25...Re7 Better was 25...Kc8. 26.Rh4 Qc7 27.Rb3+– This powerful switch to the queenside is too much for Black to bear. 27...Ke8 28.a3 Kf8 29.Be2 Re8 30.Rf3 Nh7 31.Bc1 Qe7 32.Rh1 Bf6 33.Bd3 Qe5 34.Rf5 Qd4 35.Rf4 Qc5 36.h6 g5 37.Rxf6 Nxf6 38.Qxg5 Nd7 39.Qg7+ Ke7 40.Bg5+ 1-0 16.10 Santiago Gomila Marti 2243 José Daniel Monreal Godina 1860 ICCF email 2010 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 e6 7.Be2 Be7 8.f4 Nc6 9.Qd2 Bd7 10.0-0-0 b5 11.Bf3 Rc8 12.g4 12...0-0 A) 12...Na5?! 13.g5 Nc4 14.Qd3±; B) 12...Nxd4 13.Qxd4 0-0 14.g5 Ne8 15.h4ƒ; C) 12...h6 13.h4 h5 is a bit extreme after 14.g5 Ng4 15.Nxc6 Bxc6 16.Bxg4 hxg4 17.Qd4 f6 18.h5ƒ and White will open the kingside with h5-h6; D) 12...b4 13.Nce2 d5 14.e5 Ne4 15.Bxe4 dxe4 16.Nb3!± clamps down on the dark squares. 13.g5 Nxd4 13...Ne8 14.Kb1 Na5 15.b3± 14.Bxd4 Ne8 15.Ne2!± Black has no counterplay and he soon goes down in flames. 15...Bc6 16.Bc3 Bb7 17.Kb1 Rc4 18.b3 Rc5 19.Rhe1 Qc8 20.Bb4 Rc7 21.Nd4 Qd7 22.f5+– e5 23.f6 exd4 24.fxe7 Qxe7 25.e5 Qd8 26.Bxb7 Rxb7 27.exd6 Rd7 28.h4 Kh8 29.Qxd4 a5 30.Bc5 a4 31.Re7 axb3 32.axb3 Rg8 33.Rxd7 Qxd7 34.h5 f6 35.h6 gxh6 36.gxf6 Rf8 37.f7+ Ng7 38.Rf1 b4 39.Bxb4 h5 40.Bc3 Qg4 41.Rf4 Qg3 42.d7 1-0 16.11 Krzysztof Jakubowski 2497 Petr Cerveny 2353 Czechia tt 2008/09 (5) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 d6 6.Be3 Nc6 7.Be2 Be7 8.Qd2 0-0 9.0-0-0 a6 10.f4 Bd7 11.g4 Nxd4 12.Qxd4 Bc6 13.g5 Nd7 14.h4 b5 15.h5 e5 16.Qd2± 16...Nc5 16...exf4 17.Bxf4 Nc5 18.Rhg1 Rc8 19.h6 g6 20.Bg4 Ne6 21.Be3+– 17.Bf3 Ne6 18.Rhg1 18.fxe5! dxe5 19.Qg2 Nd4 20.Kb1± is even stronger, as g5-g6 can’t be averted. 18...exf4 19.Bxf4 Nxf4 19...f5 at least forces White to find 20.Be3 f4 21.Bg4! Nxg5 22.Bxf4± with too much initiative. 20.Qxf4 Qc7 21.Kb1 b4 22.Nd5 Bxd5 23.exd5 Rac8 23...Rae8 24.Qxb4± 24.Qh2 24.Be4!+– defends and attacks. 24...Qc4 25.Rg4 Qc5 26.Qe2 Rc7 27.Rdd4 Rfc8 28.Rc4 Qa7? Black had to accept the pawn-down endgame with 28...Qb5 29.Rxc7 Rxc7 30.Qxb5 axb5 31.Rxb4±. 29.Qxe7!+– Qf2 30.Qe2 1-0 16.12 Krisztian Szabo 2539 Andras Flumbort 2469 Budapest 2014 (7) 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 2...d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be2 e6 7.Be3 Be7 8.f4 Nc6 9.Qd2 Qc7 10.0-0-0 0-0 would be our move order. 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Be3 a6 7.Qd2 Nf6 7...Be7!? and then ...Nf6 dodges the 8.f4 option. 8.f4 d6?! 8...Bb4 9.Bd3 Na5 10.a3 Bxc3 11.Qxc3 Qxc3+ 12.bxc3 d5 13.e5 Ne4 14.Nb3 Nc4 15.Bxc4 dxc4 16.Na5 Bd7! 17.Bd4 Rc8= is the main reason I didn’t recommend 8.f4, though I have essayed it with some success, and White risks nothing here. 9.0-0-0 Be7 10.Be2 0-0 11.g4 b5 12.g5 Nd7 12...Nxd4 13.Qxd4 Nd7 14.f5 (14.h4!) transposes to the game. 13.f5 13.Nxc6! Qxc6 14.a3 Nc5 15.Rhf1 Bb7 16.f5± 13...Nxd4 14.Qxd4 14...Qa5? A) 14...Bb7! 15.Kb1 Rfc8 is the only way to hold on, but it limits White to a small edge: 16.Rhf1 (16.fxe6 fxe6 17.Bg4 Nc5 18.Rde1 puts Black under some pressure too) 16...Ne5 17.h4 Bc6 18.a3² Black’s queenside play is still slower; B) If 14...Re8? 15.fxe6 fxe6 16.Nd5!+– is a useful tactic. 15.f6!+– gxf6 16.Rhg1 16.gxf6 Bxf6 17.Qxd6+– 16...Kh8 17.Rdf1 Black can’t save his king. 17...e5?! 17...Qd8 loses beautifully: 18.Nd5! exd5 19.gxf6 Bxf6 20.Rxf6 Qxf6 21.Qxf6+ Nxf6 22.Bd4 h5 23.Bxf6+ Kh7 24.Rg7+ Kh6 25.Bd3 and Black’s king is trapped while his other pieces sit at home. 18.Qd5 Rb8 19.gxf6 Bb7 20.Bh6! Bxd5 21.Bg7+ Kg8 22.fxe7 h5 23.Bxf8+ Kh7 24.Rf5 A sweet finish! 1-0 16.13 Jürgen Gburek 2460 Roberto Cerrato 2448 ICCF email 2012 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be2 e6 7.0-0 7.Be3 Be7 8.f4 0-0 9.g4 d5 10.e5 Nfd7 11.0-0 Qc7 7...Be7 8.f4 0-0 9.Be3 Qc7 10.g4 d5 11.e5 Nfd7 12.g5² Nc6 13.Rf3 Bc5 A) 13...Rd8 14.Bd3 Nf8 15.Qe1 prepares Rh3/Qh4, Ibarra Padron-De Souza, email 2005; B) 13...Nxd4 14.Bxd4 b5 15.Rh3 g6 16.Qe1 Bc5 17.Rd1 Bxd4+ 18.Rxd4 Qb6 19.Qd2² Black has survived the first wave of attack, but White’s long-term positional trumps place him in good stead. 14.Rh3! 14.Bd3 g6= 14...Rd8 14...Re8 15.Qd2 Nxd4 16.Bxd4 Qb6 17.Bxc5 Qxc5+ 18.Kf1 Nf8 19.Bd3² was not too different in Laane-Wilczek, email 2011. 15.Bf1 Nf8 16.Qd2 Nxd4 17.Bxd4 Bd7 The bishop is misplaced here and I would prefer 17...b6 18.Rd1 Ng6 to cover the kingside and see what White does. Black may well activate his bishop with ...a6-a5/...Ba6 if White plays Ne2 as in the game. 18.Ne2 b6 19.b4! Be7 20.a4 Rdc8 21.c3± White has full control of both flanks and he proceeds with poise. 21...a5 22.b5 Bc5 23.c4! 23.Bxc5 Qxc5+ 24.Nd4 Ng6 25.Qf2 Rc7 risks being a fortress for Black. 23...Bb4 24.Qe3 Rab8 25.Rc1 Qb7 26.Nc3 Ng6 27.Qf3 White has a large initiative across the board. 27...Bc5 28.Rd1 Qc7 29.Qh5 Nf8 30.Qh4 Rd8 31.Qf2 Bxd4 32.Qxd4 dxc4 33.Qxc4 Qxc4 34.Bxc4 Be8 35.Rhd3 Rxd3 36.Bxd3 f6 37.exf6 gxf6 38.Ne4 fxg5 39.fxg5 Kf7 40.Nd6+ Ke7 41.Nxe8 Rxe8 42.Be4 Rc8 43.Bc6 Rc7 44.Kf2 Ng6 45.Kf3 Ne5+ 46.Ke4 Nf7 47.h4 Nd6+ 48.Ke5 Nf7+ 49.Kf4 h6 50.g6 Nd6 51.Ke5 Nc4+ 52.Kd4 Nd6 53.g7 Nf5+ 54.Ke5 Nxg7 55.Rg1 Kf8 56.Rg6 h5 57.Rh6 Kf7 58.Rh8 1-0 Chapter 17 What others recommend... and why I disagree 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Unusual second moves 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nf6 2...g6 3.d4 Bg7 4.Nc3 is recommended by both Negi and the previous edition of Dismantling the Sicilian (henceforth referred to as ‘DTS09’), but doesn’t work for this repertoire because we want to play the Maroczy Bind against the Accelerated Dragon. 2...a6 3.c4!. There is not much to add to DTS09’s coverage of this line – White is better by playing d2-d4 in reply to ...Nc6 (avoiding the closing of the centre with ..e7-e5). 3.c3 is Negi’s recommendation, but after 3...e6 4.d4 d5 Black’s 2...a6 move proves somewhat useful in the arising positions: 5.exd5 exd5 6.Bd3 c4 7.Bc2 Bd6 and now: A) 8.Ne5 Ne7 9.Qh5 g6 10.Qf3 0-0 11.Bh6 is a variation given by Negi, but Black gets a surprising amount of compensation for the exchange after 11...Bxe5! 12.Bxf8 (less critical is 12.dxe5 Re8 13.Qf6 Nf5 14.Qxd8 Rxd8=) 12...Bxd4 13.cxd4 Qxf8 14.Nc3 Nbc6 followed by ...Be6 or ...Bf5, with good light-square play as d4 is a bit tender; B) I think White can claim a small edge by trading off Black’s space early: 8.b3!? cxb3 9.axb3 Ne7 10.0-0 0-0 11.Re1 Nbc6 12.Nbd2 Games such as Osipov-Guevara, email 2011, show that White is a bit better, though Black’s position is solid. 3.Nc3 3.e5 Nd5 4.d4 cxd4 5.Qxd4 e6 6.Bc4 Nc6 7.Qe4 d6! 8.exd6 Nf6 9.Qe2 Bxd6 10.Nc3 and Bg5 was De la Villa’s line, but Black can be prophylactic with 10...h6!?N 11.0-0 a6 12.b3 Qc7 13.Bb2 0-0 when it’s hard for White to increase the pressure on Black’s position. 3...d5 4.Bb5+ Bd7 5.e5 Bxb5 6.Nxb5 This is the line given in Negi and DTS09, but an improvement for Black is: 6...Qd7! 7.Qe2! Instead, 7.Nc3 Ng8 and ...e7-e6 gives Black a good version of the French Defence. 7...a6 8.Nc3 Ng8 9.e6! Qxe6 10.Qxe6 fxe6 11.Ng5 d4! 12.Nxe6 Kf7 13.Ng5+ 13.Nd5 Kxe6! 14.Nc7+ Kd6 15.Nxa8 Kc6 will pick up the a8-knight with ...b7-b6 and ...Kb7, which is far from clear. 13...Kg6 14.Nce4 Nf6 15.d3 e5 16.0-0 h6 17.Nxf6 gxf6 18.Nf3 Nc6 19.Nh4+ Kf7 And the endgame is more pleasant for White, but Black’s position is relatively safe. 2...Nc6 sidelines 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 Most of the time this is played with the Sveshnikov Sicilian in mind, but there are obviously many other approaches. I am recommending 3.d4 for this repertoire, but 3.Bb5 has been trendier at the top level for a while. 3.d4 3.c3 can be a nice move order trick if your opponent usually meets the Alapin with a non-...Nc6 system, but let’s focus on more critical tries. 3.Nc3 is something I was tempted to recommend, avoiding the Sveshnikov with 3...Nf6 4.Bb5, but first, 3...g6 move orders us out of the Maroczy Bind, and second, the independent line 3...e5 4.Bc4 Be7 fails to offer White real chances of an opening advantage: 5.d3 d6 (5...Nf6 6.Ng5 0-0 7.h4! is a fresh idea of Dubov’s that deserves more tests) 6.Nd2 (the other main line is 6.0-0 Nf6 7.Ng5 0-0 8.f4 Bg4 9.Qe1 exf4 10.Bxf4 Nd4 11.Qd2 Qd7, again with balanced play) 6...Nf6 7.Nf1 Bg4 8.f3 Be6 9.Ne3 0-0 10.0-0 Nh5 The engine gives White a small advantage, but the drawing method of 11.Ncd5 Bg5 12.g3 Bxe3+ 13.Bxe3 Na5! is well known, having been analysed in Kotronias’s recent Anti-Sicilians book. Black will soon trade on c4 and d5, with a balanced position regardless of which structure White enters. 3.Bb5 In principle it makes sense to have the Rossolimo in your repertoire, as it forces Black into a complex strategic battle. I’ll show a few ideas as a starting point for your own explorations. A) 3...d6 4.0-0 Bd7 5.Re1 Nf6 6.c3 a6 7.Bc4! has been scoring well for White, with the point that 7...b5 8.Bf1 weakens Black’s structure for the coming Ruy Lopez-style play, but 7...Bg4 8.d4 cxd4 9.cxd4 Bxf3 10.gxf3² also proves in White’s favour, despite the doubled f-pawns; B) 3...e6 4.0-0 Nge7 5.d4! cxd4 6.Nxd4 also gives good chances for an opening advantage (+0.25); C) 3...g6! This variation is the main reason I selected 3.d4. 4.Bxc6 In principle, the idea of 3.Bb5 is to double Black’s pawns, though we’ve already seen 0-0/c2-c3/Re1/d2-d4 as another interpretation. 4...bxc6 (4...dxc6 5.d3 Bg7 6.h3 Nf6 7.Nc3 leads to more strategic play. The computers tend to give a minute edge in the +0.1 range) 5.0-0 Bg7 6.Re1 Nh6 7.c3 0-0 8.h3 This position has been at the height of fashion for the last 12 months. Black is holding his own with 8...f5 (or Gelfand’s dynamic 8...d5 9.d3 c4!) 9.e5 Nf7 in practice, but engines tend to give White approximately a +0.15 edge, so there’s definitely scope to set Black problems. 3...cxd4 4.Nxd4 Qb6!? 5.Nb3 Nf6 6.Nc3 e6 7.a3! Despite not being popular anymore, this old recommendation still looks good for an edge. 7.Qe2 Bb4 8.Bd2 0-0 9.a3! is the line I originally analysed, but Negi beat me to it in his book. Mista-Azarov, Katowice rapid 2017, is a model example of White’s chances, but an important line that goes unmentioned by Negi is 9...Be7 10.0-0-0 d5 11.exd5 Nxd5!, which has scored well in several games in the last year. Objectively speaking though, White should still be better after 12.g3! Bf6 (12...Nxc3 13.Bxc3 e5 14.Bg2 is just a transposition) 13.Ne4 Be7 14.Bg2 e5 15.Nc3! Nxc3 16.Bxc3 Be6 17.Bxc6!? (17.Bd5 Bxd5 18.Rxd5 Rad8 19.Rxd8 Qxd8 20.Rd1 Qc7 21.Kb1² keeps the position a bit more tense) 17...Qxc6 18.Qxe5 Bf6 19.Qc5 Bxc3 20.Qxc3 Qxc3 21.bxc3 Only White can win this endgame, though Black should hold it. 7...Be7 7...Qc7 8.Bg5!? was given in DTS09, but an interesting reply is 8...Be7 9.f4 0-0!? 10.e5 Nd5 11.Nxd5 exd5 12.Bxe7 Nxe7 13.Bd3 d6 14.exd6 Qxd6 with only a tiny edge for White. 8.Bf4 0-0 9.Bd6 This was the original recommendation, but the computer move 9...a5! threatens an annoying ...a5-a4, and the direct 10.Na4 Qa7 11.Bxe7 Nxe7 12.e5 Nfd5 13.c4 b5! 14.cxb5 Bb7 (or also 14...f6!?) gives Black a substantial lead in development for the pawn. Lowenthal & Kalashnikov 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 e5 5.Nb5! 5...d6 5...a6?! 6.Nd6+ Bxd6 7.Qxd6 Qf6 and now: A) 8.Qxf6 Nxf6 9.Nc3 Nb4 10.Bd3 is Negi’s recommendation, but the rare 10...b5!? 11.Bg5 Bb7 12.0-0 Rc8, with ideas of ...Nxd3 and ...d7-d6, is not easy to crack. For instance, the obvious 13.a3 Nxd3 14.cxd3 d6 15.Bxf6 gxf6 16.f4 Ke7 17.Rf3 Rc5 18.Raf1 Rf8, while clearly giving White some advantage, also holds Black’s position together; B) 8.Qc7!? is an interesting alternative that scores very well for White. The main line is the forcing 8...Nge7 9.Nc3 Nb4 (Black needs to play this immediately, else after Be3 White is ready to meet ...Nb4 with 0-0-0, killing Black’s counterplay) 10.Bd3 d5 11.0-0 d4 12.Na4 Qc6! 13.Qxc6+ Nexc6 14.Nb6 Rb8. White scores heavily in this endgame, but objectively his edge is only quite small after 15.f4 f6 16.f5 (16.Rf2 Be6 17.Bf1!?² may be even better, keeping the bishop pair advantage even at the price of the a2-pawn. Black could take on d3 earlier, but that tends to give White a strong initiative based on dominating the e6-bishop with f4-f5, or opening the position with fxe5 if Black didn’t find time to castle) 16...Kd8 17.a3 Nxd3 18.cxd3 Bd7 19.Bd2 Kc7 20.Nd5+ Kd6 21.g4 and White’s better minor pieces give him the winning chances in the position. 6.N1c3 a6 7.Na3 Be7!? Negi recommends the trendy 8.Be3 Nf6 9.Nc4 b5 10.Nb6 Rb8 11.Nxc8 Qxc8 12.Be2 0-0 13.0-0 for a small bishop pair advantage, but White made no headway in Ponomariov-Cornette, Internet 2017: 13...b4 14.Nd5 Nxe4 15.a4 a5 16.Rc1 (or 16.Bb5!? Bd8=) 16...Bg5 17.Bxg5 Nxg5 18.Bb5 Kh8 19.c3 b3 20.Qxb3 Na7 21.c4 Nc6 And White’s dark squares were too vulnerable for an edge. Accelerated Dragon 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 g6 5.Nc3 Bg7 6.Be3 Nf6 7.Bc4 0-0 8.Bb3 This was the original recommendation, and is also Negi’s preference. However, it’s quite telling that while most strong GMs meet 3.d4 with the Sveshnikov, against 3.Nc3 they are very willing to transpose to the Accelerated Dragon with 3...g6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4. Furthermore, there are a few variations where White struggles to prove an edge. 8...d6 A) 8...Re8!? was a tough line for Negi to prove an edge against, and my attempt 9.f3 e6 10.f4!? also comes up short after 10...d6! 11.Qf3 Na5! 12.0-0 b6= when White is unable to make e4-e5 or f4-f5 breaks work to his liking; B) 8...d5!? 9.exd5 Na5 has emerged as the main trend, as Negi’s recommendation of 10.0-0 Nxb3 11.Nxb3 b6 12.d6! exd6 13.Bd4 (13.a4!?, to loosen up the queenside, could be investigated, but Black should be OK) 13...Re8 14.Qd2 Bb7 15.Rfe1, while probably best, only gives a symbolic edge (+0.15) after 15...Re6!?. 9.f3 Bd7 10.Qd2 I’m recommending 9.0-0-0 against the Dragon, so we’ve already been move ordered into the Yugoslav Attack. 10.h4!? is also covered by Negi, though he rightly states that Black is fine with correct play. 10...Nxd4 11.Bxd4 b5 Vachier-Lagrave failed to prove a white edge in two very recent games against Radjabov and Giri. 12.a4 DTS09’s recommendation 12.h4 a5 13.a4, while still popular, fails to offer anything tangible as after 13...bxa4! 14.Nxa4 is well met by Negi’s proposed 14...h5 or 14...Rb8=. 12...b4 13.Nd5 Nxd5 14.Bxg7 14.exd5 Bxd4 15.Qxd4 15...Re8! This seems to improve on Negi’s analysis, with the idea 16.Qxb4 a5 17.Qh4 (17.Qd4 e5; 17.Qd2 e5 18.0-0 Rb8 – the b3-bishop is such a bad piece that White cannot move his queenside majority. Black has full compensation – 0.00) 17...Qc7 with long-term compensation based on the bad b3-bishop. A correspondence game confirmed that Black is holding his own. 14...Kxg7 15.exd5 Qb6 16.h4 h5 17.0-0-0 Qa5 18.Qd4+ 18.g4 was MVL’s very recent try against Giri at Norway Chess, but I don’t think he achieved anything from the opening after 18...Bxa4 19.Kb1 Bxb3 20.cxb3 Rh8=. 18...Kg8 19.g4 Bxa4 Negi concludes that White objectively has nothing. 9.Bxf6 Sveshnikov 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 b5 A) 8...Be7 is analysed deeply by Negi, but it’s rare and doesn’t require deep knowledge. For example, 9.Nc4 0-0 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.Qxd6 Be6 12.Qxd8!? Raxd8 13.Ne3² is one lazy route to a small edge; B) 8...Be6 9.Nc4 Rb8 10.a4 was recommended by Negi, but subsequent practice has shown that 10...Nb4! 11.Nd5 (11.Bxf6 Qxf6 12.Be2² is stronger) 11...Nbxd5 12.exd5 Bf5 13.Bd3 Bg6!? doesn’t give White a substantial edge. 9.Bxf6 gxf6 10.Nd5 10...f5 10...Bg7 11.Bd3 Ne7 12.Nxe7 Qxe7 the Novosibirsk Variation, has been under a cloud for some time, and recently Negi demonstrated some of the problems in the main line 13.0-0 0-0 14.c4 (14.Qf3 was the DTS09 recommendation, but it’s been neutralised by 14...d5! 15.exd5 e4 16.d6 exf3 17.dxe7 Re8 18.Be4 Ra7! 19.Bxf3 f5 20.c3 b4! and the active bishop pair gives Black drawing compensation for the pawn) 14...f5 15.Qh5 Rb8 16.exf5 e4 17.Rae1 Bb7. For what it’s worth, the most common move 18.Qg4! seems to offer the largest advantage, if we’re accurate. I’ve included a fair bit of analysis for those wanting to play 9.Bxf6: A) 18...bxc4 19.Bxe4 Bxe4 20.Rxe4 Qf6 21.Rxc4 Rxb2 22.Rd1 Rxa2 23.Nc2 gives White a dominant position, with the better minor piece, more active rooks and safer king; B) 18...Kh8 19.Bxe4 B1) 19...Bxb2 20.Re3 Rg8 (20...Bxe4 21.Rxe4 Qf6 22.Nc2 bxc4 23.Rxc4 d5 24.Rb4 Bc3 25.Rxb8 Rxb8 (ShirovMarkos, Montcada 2009) 26.Qf3! is likewise a safe extra pawn for White) 21.Qf3 Bxe4 22.Rxe4 Qb7 23.Rfe1 Qc6 24.R1e2 Bf6 25.cxb5 axb5 26.g3± It’s not clear what compensation Black has for the pawn; B2) 19...Rfe8 20.Bd3 Qxe1 21.f6! Bh6 22.Qh5 Qd2 23.Qf5 Be4 24.Bxe4 Rxe4 25.Qxe4 Qxb2 26.Qd3 b4 27.Nc2 Qxf6 28.g3 a5 29.Nd4 and White has a stable positional advantage, see the model game Catt-Tinture, email 2010; C) 18...Rfe8 19.cxb5 C1) 19...axb5 20.Bxb5 Red8 (20...Rec8 21.f3! Kh8 22.fxe4 is similarly in White’s favour) 21.f3 Kh8 22.fxe4 Bxb2 23.Nc4 Bc3 24.f6! Bxf6 25.Kh1± White had consolidated his extra pawn in Loginov-Blair, email 2013; C2) 19...d5 20.bxa6 Bc6 21.Be2 (21.Rc1 exd3 22.Rxc6 Qe2 23.h3 Rxb2 24.f6 Qxg4 25.hxg4 Rxa2 26.Nb1 Bf8 27.Rc3 Rxa6 28.Rxd3 Rxf6 29.Rxd5² – this pawn-up endgame arose in Topalov-Carlsen, Nanjing 2009, though Black didn’t have trouble holding the draw) 21...Kh8 22.Rc1 Bd7 23.Rb1 Rg8 A draw was agreed in Bach-Heinke, email 2012, but 24.b4! looks good for White, albeit not entirely clear. 11.Bd3 Be6 12.0-0 12.c3 Bg7 13.Nxb5! axb5 14.Bxb5 is Negi’s recommendation against the Sveshnikov, and hasn’t seen many developments. Having checked the line for myself, I’ve come to the same conclusion that it is objectively equal (especially if Black is familiar with the relevant correspondence games), but easier for White to play. 12...Bxd5 13.exd5 Ne7 14.c3 Bg7 14...e4 15.Be2 Bg7 admittedly avoids the 14...Bg7 15.Qh5 line the way I want to play it. 15.Qh5!? 15.Nc2 is still a fine line, though strong players will be ready for it: 15...0-0 16.a4 (16.Qh5 e4 17.Be2 transposes to 15.Qh5) 16...e4 17.Be2 bxa4 18.Rxa4 Qb6 (if 18...Rb8 19.Ra2 a5 20.Ne3 and Nc4 is annoying) 19.Rb4 Qc5 (19...Qc7!?N 20.Qd2 a5 21.Rb5 Ng6= Black’s kingside counterplay will arrive in time) 20.g3! This isn’t mentioned by Kotronias in GM Repertoire: Sicilian Sveshnikov so this could be a suitable one-game weapon. The point is that White will give the d5-pawn for an initiative with the opposite-coloured bishops: 20...Qxd5 (20...Bf6?! looks slow. 21.Re1!? (21.Ne3 Bg5 22.Qd2²) 21...Qxd5 22.Ne3°) 21.Qxd5 Nxd5 22.Rb7 Rab8 23.Bxa6 Rfc8 24.Rd1 Admittedly the two correspondence games from here were drawn after 24...Nc7, but I feel in a practical game White could still set a few problems (around +0.15 to modern engines). 15...e4 A) 15...Qc8?! 16.Rad1 e4 17.Bb1! 0-0 18.Nc2 and Ne3 gives White a clear advantage, as Black has trouble defending his centre against an undermining f2-f3; B) 15...Qd7?! 16.Rad1 Rc8 encounters similar problems: 17.Nc2! (17.Bb1 still looks good, but we can even save this tempo) B1) 17...0-0? is a common mistake – Black doesn’t have time for slow measures against our ambitious set-up: 18.f3! (paralysing the kingside pawns) 18...h6 19.Kh1 f4 20.Rg1 Kh8 21.g4 f5 Now Van Kempen-Sender, email 2000 is a nice win for White, but we can even improve on 22.gxf5 with 22.Nb4!+– when Black is unable to cope with an eventual Nc6, trading Black’s last defender of the light squares; B2) 17...e4 18.Be2 0-0 is better, but this is just an improved version of our main line after 19.g3. Black probably should sacrifice a pawn with ...f5-f4 soon to avoid being clearly worse, but 19...f4!? 20.gxf4 f5 21.Kh1 Ng6 22.Qg5 doesn’t give Black full compensation for the pawn. He has scored well in practice though, so let’s extend the line: 22...Bf6 23.Qg3 Kh8 24.Bh5! Rg8 25.Qe3 Qg7 26.Bxg6 Qxg6 27.Qh3 Qg4 28.Qxg4 Rxg4 29.f3 Rxf4 30.fxe4 Rxe4 31.Rxf5² White’s extra pawn is more important than Black’s activity. 16.Be2! Unfortunately, the 16.Bc2 of DTS09 is toothless under engine scrutiny, as already demonstrated by Kotronias, but the positional plan of Nc2-e3 forces considerable accuracy from Black. 16...0-0 A) 16...f4 17.Nc2 0-0 transposes to the main line, but 17.Bg4!? looks good for White; B) 16...b4? 17.cxb4 Bxb2 18.Rab1 Bxa3 19.Rb3 Bxb4 20.Rxb4² gives White a neat initiative for the pawn; C) 16...Qd7 threatens ...Nxd5, but we can ignore it! 17.Nc2!?N 17...Nxd5 18.Bg4 Ne7 (18...fxg4 19.Qxd5 0-0 20.Qxe4 Rfe8 21.Qd3 White has a stable positional advantage with the knight coming to d5/f5) 19.Bh3 (Black cannot avoid the loss of his extra pawn) 19...Qe6 20.Ne3 Qg6 21.Nxf5! Nxf5 22.Qxf5 Qxf5 23.Bxf5 d5 24.Rfd1 Rd8 25.a4 With rooks on the board, Black does not have a guaranteed draw by any means; D) 16...Qc8 17.Nc2 Nxd5 18.Bg4!, as in Kraft-Grube, email 2011, is likewise a bit better for White. 17.Nc2 Compared to 15.Nc2, our queen is very actively placed, and we have a few different plans – Ne3/g3 to pressure f5, f2f3 to open the kingside, and the familiar a2-a4 to make inroads on the queenside. 17...Kh8! This is the rarest move, but also the strongest! First I’ll indicate how White can fight for the advantage after the other options: A) 17...Qc8?! 18.Rad1 scores disappointingly for Black, as in e.g. Salgado Lopez-Baules, Quito 2012; B) 17...Qd7 held up for Black in several old correspondence games, so we should be precise: 18.f3 B1) 18...b4 19.Nxb4 a5 doesn’t convince me after 20.Nc6!; B2) 18...Qa7+ 19.Kh1 Qc5 20.Rad1 Rae8 was Salvador Marques-Noble, email 2008, but an improvement is 21.Nd4! b4 22.Nxf5 Nxf5 23.Qxf5 bxc3 24.bxc3 Re5 25.Qd7 e3 26.c4² and while the engine overestimates White’s extra pawn, I’d still prefer his chances; B3) 18...Rae8 19.Rad1 (19.Kh1!? Nxd5 20.fxe4 Nf6 21.Qxf5 Qxf5 22.Rxf5 Nxe4 23.Bf3 Nf2+ 24.Kg1 Nd3 25.Rb1 Re5! gives Black sufficient counterplay) 19...Ng6 20.f4 a5 was Woznica-Thierry, email 2012. White seems to be a bit better after 21.Kh1! with the idea of Ne3/g2-g4; C) 17...Re8 with the idea of ...Nxd5 and ...Re5 used to appeal to me, but a good answer is 18.g3! Nxd5 (18...f4 is a typical sacrifice for counterplay, but keeping control of the light squares with 19.Bg4!² is more important) 19.Qxf5 Re5 20.Qh3 Qb6 (or 20...Qc7 21.f4!). Ivanovic-Kosic, email 2010, continued 21.a3 and was eventually drawn, but my improvement is 21.Rad1! Qc5 22.Kh1² when f2-f4 next move will prompt positional concessions from Black. Aagaard once wrote that Black needs clear counterplay to make oppositecoloured bishops Sveshnikov positions work for him, and I’m not sure how he achieves that counterplay here; D) 17...Rc8 with the idea of ...Rc5 is the most common move, but with almost no recent games in this variation, that’s not necessarily an indicator of future practice: 18.Ne3 f4 (18...Qd7 19.g3! is the familiar bind, as in Hertel-Haugen, email 2006. If Black seeks queenside counterplay, 19...Rb8 20.a3 a5 21.Kh1! to prepare f2-f3 is quite strong) 19.Nf5 Re8 20.a4 (this is well timed with Black’s rook committed to c8; 20.Bg4 Rc4 21.g3 Ng6) 20...Ng6 (20...bxa4!? 21.Rxa4 Nxf5 22.Qxf5 Rb8 (Bernal Varela-Baranowski, email 2011) led to a worse but holdable endgame for Black. We can improve on that with 23.Rxe4! Rxe4 24.Qxe4 Rxb2 25.Bd3 with a characteristic opposite-coloured bishop initiative) 21.axb5 axb5 22.Ra6 Bf8 23.Bxb5 Re5 24.Qh3 f3! 25.g3 Rb8 26.c4 Qf6 27.Nh6+ Kh8 28.Ra7 Re7 29.Rxe7 Nxe7 30.Ng4; 17...f4 18.f3 f5 (18...e3 19.Qg5 Ng6 20.Qxd8 Rfxd8 21.a4 bxa4 22.Nb4 a5 23.Nc6 Rd7 24.Rxa4 Rb7 25.Ra2 gives White some slight chances as he has the better bishop and knight, plus the e3-pawn is under control) 19.fxe4 fxe4 20.Qg4!? This seems the best try for an edge, targeting the advanced pawns: 20...Qc8! 21.Rxf4 Rxf4 22.Qxf4 Qc5+ 23.Kh1 Qxd5 24.Ne3 Qe5 25.Qxe5 Bxe5 26.g3 d5 27.a4 Rb8 28.axb5 axb5 29.Nc2 White has some winning chances with his better structure, as the addition of the knights and rooks favours the stronger side with opposite-coloured bishops. 18.a4 A) 18.Rad1 f4 19.Nd4 Be5 20.Rfe1 was Greco-Zemlyanov, email 2014, but OTB I would be concerned about 20...f3!? 21.gxf3 Ng6 with a dark-square initiative for the pawn; B) 18.Ne3!?N is probably the trickiest, but here too Black should be fine after the precise 18...f4 19.Nf5 Re8! 20.Bg4 (20.Qxf7?! Nxf5 21.Qxf5 f3!) 20...Ng6 followed by ...Re5. 18...bxa4 19.Rxa4 Rb8 20.Ra2 a5! By keeping the a-pawn as long as possible, Black buys enough time for create good kingside counterplay: 21.Ne3 21.Rfa1?! f4 22.Bf1 f5 is still equal, but definitely easier for Black to play. 21...f4 22.Nf5 Ng6!N 23.g3 Re8 24.Rfa1 Qf6 White should already accept he is not better and simplify with 25.Rxa5 Rxb2 26.Ra8 Rf8 27.Bf1= Now we can understand why I found 9.Nd5 a more promising variation to recommend. 2...e6 sidelines 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 3.Nc3 followed by d2-d4 avoids some of the sidelines without move ordering us out of our repertoire, as 3...Nf6 4.e5 Nd5 transposes to my main recommendation against the Nimzowitsch Variation. But in truth, we should welcome inferior moves by the opponent. 3...cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 5...Bb4 6.e5 Nd5 7.Bd2 Nxc3 8.bxc3 is the usual recommendation against the Pin Variation, but anticipating Qg4 with 8...Bf8!? is not so easy to refute, e.g. 9.Bd3 a6 10.Qg4! Qc7N 11.Qg5! Nc6 12.Nxc6 dxc6 13.0-0 Bd7 and though the engine gives White an edge, Black can catch up in development with ...c6-c5/...Bc6/...g7-g6/...Be7, and White must be quite accurate to keep any pressure. 6.Ndb5 6.Nxc6 bxc6 7.e5 Nd5 8.Ne4 is the main alternative, as analysed extensively by Kotronias/Semkov in Attacking the Flexible Sicilian. I haven’t found a way for Black to fully equalise, but a notable omission was 8...Qc7 9.f4 Qa5+ 10.c3 Be7 11.Bd3 Ba6! 12.0-0 Qb6+ 13.Kh1 (13.Rf2 0-0 14.c4 f5 15.exf6 Nxf6 16.c5 Qb7 17.Nxf6+ Rxf6 18.Bxa6 Qxa6 is a typical position that optically looks better for White, but in reality, Black can defend his d7-weakness and hold) 13...Bxd3!N 14.Qxd3 f5 15.exf6 Nxf6² and compared to the immediate 12...Bxd3, White is slower to play Be3 because of the hanging b2-pawn. White’s position is still easier to play with one less pawn island, but Black can sit on the position with ...Rd8 and ...0-0, when it’s not easy for White to make progress. 6...Bb4 7.a3 Bxc3+ 8.Nxc3 d5 9.exd5 exd5 9...Nxd5 10.Nxd5 exd5 11.Bd3 Qe7+ 12.Qe2 Qxe2+ 13.Kxe2= Negi advocates playing this endgame, but subsequent draws have demonstrated that White is unable to utilise his small edge. 10.Bd3 0-0 11.0-0 d4 12.Ne2 Bg4 13.f3 Bh5 14.Bg5 This was recommended in both DTS09 and Negi. In the 2...e6 sidelines chapter I show how Black can equalise, while conceding that I haven’t found a clearly superior alternative. Paulsen 4...a6 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 a6 5.Bd3 This is Negi’s recommendation in his book. Once again, I wanted to offer something different to other books, though I do have a solution to the one problem Negi had in proving a white advantage. 5.c4 Nf6 6.Nc3 is the Attacking the Flexible Sicilian recommendation, and I ultimately agree with their conclusion that White should obtain a small edge, and I couldn’t find many improvements over Kotronias/Semkov’s analyses. 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Bd3 Nf6 7.f4 was the DTS09 recommendation, but I update the coverage in a couple of illustrative games in Chapter 9 to show why I prefer 7.0-0. 5...Bc5 6.Nb3 Be7 7.Qg4 g6 8.Qe2 d6 9.a4!? I was first shown this idea by the former second of Anand, GM Surya Ganguly. 9.0-0 Nd7 10.a4 (10.Nc3 Qc7 11.Bd2 h5! was Negi’s main line, where he shows that with perfect play Black can maintain equality. That gave me confidence in recommending 5.Nc3 even when I couldn’t prove a white advantage in every single line) 10...Ne5 is what I’m trying to avoid with 9.a4. 9...b6 A) 9...Nc6 10.a5 Nf6 11.Bh6²; B) 9...Nd7 10.a5 Ne5 (now we gain some advantages by delaying ...0-0) 11.Nc3 Bd7 (11...Nf6 12.Bh6!?ƒ) 12.0-0 Nf6 13.Bh6 Nfg4 14.Bd2 0-0 15.f4 Nxd3 16.cxd3 Nf6 17.Be3² transposes to a theoretical position considered good for White (17.f5!? requires testing). 10.Na3 Nd7 11.Nc4 Bb7 12.0-0 I am confident in White’s chances for an advantage after this transposition, though I leave this for the readers to investigate. Taimanov 4...Nc6 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 5...Qc7 5...a6 is a tricky move order for the Be3 exponent: A) 6.Be3 Nf6 7.Qf3 was the Kotronias/Semkov recommendation (7.f4 Bb4 8.Bd3 was the DTS09 variation, but subsequently 8...e5! 9.fxe5 Nxe5 10.0-0 d6 with the follow-up 11.Kh1 Bxc3 12.bxc3 h6! shut it out as a bid for an edge). I show in my analyses how hard it is to prove an edge after 7...d6!, which goes unmentioned in their book; B) 6.Nxc6 bxc6 7.Bd3 d5 8.0-0 Nf6 9.Re1= Both Negi and Kotronias/Semkov focus on this line, but my comment on the discussion is that 9.Qf3! is the way for White to show an edge. 6.Be3 6.g3!? a6 7.Bg2 Nf6 8.0-0 as recommended in Modernised: The Open Sicilian is a tough line to fully equalise against, but it would not have been practical to also cover the g2-g3 Scheveningen positions. 6...a6 6...Nf6 7.f4! Bb4 8.Ndb5 Qa5 9.e5 Nd5 10.Bd2 Nxc3 11.bxc3² is White’s best line, but it was already deeply analysed by Negi and Kotronias/Semkov, and there haven’t been many developments since. 7.Qf3! 7.Qd2 was recommended by Negi and DTS09, but I was unable to prove an edge in the trendy variation 7...Nf6 8.0-0-0 Be7! 9.f3 b5 followed by ...Nxd4/...Bb7: 10.Kb1! (10.Nxc6 dxc6 11.g4 e5 12.h4 Be6 13.Qf2 was Negi’s main recommendation, but Kotronias/Semkov showed a good antidote: 13...Rd8!?N 14.Rxd8+ Qxd8 15.Bh3 Nd7 16.g5 Bxh3 17.Rxh3 0-0! and I can confirm that after 18.Rh1 f6 19.Qg3 Qe8 Black is completely safe) White scores well and Black must be extremely precise against this. I offer a few variations as a starting point for your own investigations: 10...Bb7 (10...Nxd4 11.Bxd4 Bb7 12.Qg5!² is the point behind 10.Kb1; 10...Ne5 11.g4 0-0 12.g5 Nh5 13.f4 Ng4 14.e5 Bb7 15.Rg1 b4 16.Rxg4 bxc3 17.Qxc3 Qxc3 18.bxc3 Rfc8 gives White some winning chances with the extra pawn. One might check Cornejo-Strautins, email 2012) 11.Bf4! e5 12.Nf5 exf4 13.Nd5 Qb8 (13...Nxd5 14.exd5 Nb4 15.c4! gave White chances for an advantage in Anand-Movsesian, Dubai 2014) 14.Nxg7+ Kf8 15.Nf5 Bd8 16.Nxf4 h5 17.g3 Qe5 18.Bg2 Ne7 19.Nh4 a5 20.Nd3 A draw was agreed in Epure-Leal, email 2014, but I would much prefer White in practice after 20...Qc7 21.e5 Ne8 22.f4². 7...Nf6 A) 7...Ne5 8.Qg3 h5 9.0-0-0 (9.h4 Nf6 10.0-0-0 b5 11.a3 d6 12.Bg5 Bb7 13.Be2 Rc8 14.Bxf6 gxf6 15.f4 Nc4 16.Rh3² was ATFS’s main line after 9.h4, but I show a nice alternative with Bxb5 in the chapter) 9...h4 10.Qh3 is the main line, but I found White was scoring poorly in practice despite ATFS’s exhaustive (and generally correct) analyses, so I went with their second recommendation; B) 7...Bd6 8.0-0-0 Be5 I found I disagreed with some of Kotronias/Semkov’s conclusions – perhaps they weren’t aware of Avrukh’s detailed CHOPIN analyses: B1) 9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.Bd4 Bxd4 11.Rxd4 Nf6 12.Qg3 Qxg3 13.hxg3 d5 ATFS claim a small edge for White, Avrukh indicates equality. The truth is probably in the middle. 14.Ra4!?N (this was my attempt to improve on Avrukh’s work; 14.f3 h6!N 15.g4 0-0=) 14...Ke7 15.f3 (if White achieves Ra5/Bd3/g3-g4 he can claim some pressure, but Black can cross this plan; 15.Be2 h6 16.exd5 cxd5=) 15...a5! 16.g4 Nd7 17.Rd4 Rb8 18.exd5 exd5! This is the key idea for Black to equalise. The engine will give a +0.2 edge for White, but I don’t see a way to exploit it, for example: 19.Ra4 Ra8 20.g5 Nc5 21.Rah4 Bf5=; B2) 9.g3 b5! 10.Qe2 Bb7 11.f4 Nxd4 12.Bxd4 Bxd4 13.Rxd4 Qc5 14.Qd2 Bc6 15.Bg2 b4 16.Nd1 a5 17.e5 ATFS gives White a small edge, but the engines overvalue White’s space advantage at first, and Black looks to be fine as we play out natural moves for both sides: 17...Ne7 18.Ne3 0-0 19.Rd1 Rab8 20.Rc4 Qa7 21.Bxc6 dxc6 22.Qd4 Qa8! and ...Nd5 quickly balances the game. 8.0-0-0 Ne5 9.Qg3 b5 10.f4 Neg4 11.Bg1 b4 12.Na4 h5 13.Bd3 Somewhat amusingly, I drew the reverse conclusion to Kotronias/Semkov – 13...Bb7 equalises but not 13...d5 ! 13...Bb7! 13...d5 14.e5 Ne4 15.Bxe4 dxe4 16.Nb3! Bb7 This was played in Salem-Fier, Dubai 2017. Now an improvement is 17.Nb6! Rd8 18.Rxd8+ Qxd8 19.Na5 Bd5 In his notes to the game, Fier claims a small edge for White, which is correct: 20.Nac4 Qc7 21.Qb3 Bc6 22.h3 Nh6 23.g4 Be7 (weaker is the pawn sacrifice 23...e3 24.Rh2 Be7 25.Qxe3 0-0 26.Rd2!±) 24.Qg3 0-0 25.Be3 Bb5 26.b3 Bc5 27.Bxc5 Qxc5 28.Qe3 Qxe3+ 29.Nxe3² Black’s pieces are very ineffectively placed in this endgame. 14.h3 h4 15.Qf3 Nh6 16.Bf2 d5 17.e5 17.exd5 Bd6 The arising complications are suited to deep engine analysis, but I worked it all out to equality. I’ll give just two sample lines: A) 18.Bxh4 Bxd5 19.Qf2 Bxf4+ 20.Kb1 g5 21.Rhf1 Nhg4 22.hxg4 Rxh4 23.g3 Nxg4 24.Qe2 Bxg3 25.c4 Bb7 26.Qxe6+ fxe6 27.Bg6+ Kd7 28.Nb5+ Bd6 29.Rf7+ Kc8 30.Nxc7 Ne5 31.Nxa8 Nxf7 32.N8b6+ Kd8 33.Bxf7 Ke7 – it’s White who is fighting for a draw here; B) 18.f5 Bxd5 19.Qe2 e5 20.Nb3 0-0 21.Nb6 Bxg2 22.Nxa8 Bxa8 23.Rhe1 e4 24.Bxa6 Nxf5 This is a difficult position for a human to fully understand, but I couldn’t find a way for White to improve his position after 25.Kb1 Bg3 26.Rf1 Be5!=. 17...Ne4 18.b3 This was ATFS’s novelty, but I found a counter-improvement. I verified the book’s conclusion that 18.Bxh4 Nf5 19.Bf2 Nxf2 20.Qxf2 Nxd4 21.Qxd4 g6 gives Black full compensation for the pawn. 18...Rc8! 19.Qe2 19.Bxh4 Nf5 20.Bf2 Nxf2 21.Qxf2 Nxd4 22.Qxd4 Bc6= is a better version of 18.Bxh4. 19...Be7 20.Bxe4 dxe4 21.Rd2 0-0 22.Rhd1 Rfd8 23.Kb1 a5 The engine gives 0.00, which seems accurate. 2...d6 sidelines 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 3.Bb5+ Nd7 4.0-0 a6 5.Bd3 Ngf6 6.Re1 is the main alternative to the Open Sicilian, and may suit those comfortable in Ruy Lopez positions. However, this falls outside the scope of our coverage. 3...cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 The Prins Variation 5.f3 has lost its surprise value and 5...e5 6.Nb3 d5 7.Bg5 d4! 8.c3 Nc6 9.Bb5 9...h6! 10.Bxf6 Qxf6 11.cxd4 Bb4+ 12.Nc3 0-0= is an off-putting gambit developed since the publication of Sergey Kasparov’s Steamrolling the Sicilian. 5...Bd7 6.Bg5 This is given in both DTS09 and GM Repertoire vs. the Sicilian 3. A) After my recommendation 6.f3!? e5 7.Nb3 Be7 8.Be3 0-0 9.Qd2 a5 10.a4! Na6 11.0-0-0 Nb4 12.g4 Be6 we’ve transposed to the 10...a5 Najdorf. Incidentally, in the previous edition, 11.Bb5 was recommended from the Najdorf move order, but it’s been established that 11.a4! refutes the variation, as I cover in the chapter; B) 6.Be3 might appear a more flexible move order, but it permits 6...Ng4 7.Bg5 h6 8.Bh4 g5 9.Bg3 Bg7 10.h3 Ne5 11.Nf5 Bxf5 12.exf5 Nbc6 reaching the 6.Be3 Ng4 Najdorf, but without ...a7-a6 ! White can try to use the exclusion to his advantage in the analogous 13.Nd5 e6 14.fxe6 fxe6 15.Ne3 Qa5+ 16.c3 Nf3+ 17.Qxf3 Bxc3+ 18.Kd1 Qa4+ 19.Nc2 Bxb2 20.Rc1! Ke7 21.Bd3 Bxc1 22.Kxc1 Rac8 23.Kb1, with an edge, but it seems a lot simpler to avoid it. 6...e6 7.Ndb5 A) 7.Qd2 was Negi’s recommendation, but I’m not convinced that 7...h6 8.Bxf6 Qxf6 9.Ndb5 Bxb5 10.Bxb5+ Nc6 gives White a real advantage if one follows the engine’s first line at a high depth; B) 7.f3 was the DTS09 recommendation, but after 7...Be7 8.Qd2 0-0 9.0-0-0 Nc6 we’ve been move-ordered into an f2f3 Rauzer, where I recommend an f2-f4 approach against ...0-0 lines. 7...Bxb5 8.Bxb5+ Nc6 9.Qf3 Be7 White’s position looks better with the bishop pair, but it’s not easy to prove conclusively. For instance, forcing play with 10.e5 Nd5 11.Be3!? a6 12.Ba4 Nxe3 13.Bxc6+ bxc6 14.Qxc6+ Kf8 15.fxe3 dxe5 16.0-0 Qc8 17.Qe4 f5! 18.Qxe5 Bf6 19.Qa5 Qb7 gives Black excellent compensation, with the preferable minor piece and play down the queenside files. Scheveningen 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 After 2...e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nc6 5.Nc3 d6 6.Be3 Nf6 I recommend the rare 7.Qe2, which was mentioned by Negi. 7.f4 Be7 8.Qe2² is Negi’s recommendation, which remains very rare, probably because 7.Qe2 is an improved version where we can frequently play the g4-g5 charge without the preparatory f2-f4 (8.Qf3 is the ATFS recommendation, and also good for an edge). 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e6 6.g4! 6.Be3 was the DTS09 recommendation, with a likely transposition to the Najdorf after 6...a6. My initial issue was that after 6...Be7 White is slightly move-ordered out of the repertoire, now that I am not recommending the English Attack against the Najdorf. Those who have Negi or ATFS could probably transpose to their lines with 7.f4 0-0 8.Qe2N or 8.Qf3 as Black doesn’t seem to have better than ...Nc6 in any case. 6...h6 7.Rg1! This was the ATFS recommendation, and I’ve expanded on their analyses in the chapter. 7.h4 Nc6 8.Rg1 is the old main line and Negi’s recommendation. Kotronias/Semkov already offered some ideas for Black with 8...d5! and I don’t have much to add to their analyses. Dragon 5...g6 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 0-0 8.Qd2 Nc6 9.Bc4 This was recommended by Negi and DTS09, because they were forced into this variation in any case by their 5.Nc3 Accelerated Dragon recommendation. 9.0-0-0 d5 10.Qe1! was recommended in Modernized: The Open Sicilian and while the theory has developed somewhat since, you’ll see in Chapter 12 that I agree with their conclusion that White is better. 9...Bd7 10.0-0-0 Rc8 11.Bb3 Nxd4 12.Bxd4 b5! This pawn sacrifice defines the Topalov Variation, and it’s the one line of the Dragon Variation where Negi is unable to prove a white advantage. 13.Nd5 Nxd5 14.Bxg7 Kxg7 15.exd5 a5 16.a3 Kg8! This prophylaxis against checks was virtually unknown back when DTS09 was written, but anticipating checks in this way is annoying for White. 17.Rhe1!? I would recommend this move as it scores very well for White, but it doesn’t offer a workable edge either. Negi analyses 17.h4 to equality, and I haven’t found an improvement. 17...Rc5! 18.Re3 b4! 19.axb4 axb4 20.Qxb4 Qa8 21.Bc4 Bf5 21...Re8?! 22.Ra3 Qc8 23.Bb3! Qc7 24.Rd2 Rc8 25.g4! gives White a stable advantage as he has fully consolidated the queenside. 22.Ra3 Qc8 23.b3 Qc7 24.Qd2 Rc8! The engine generally rates White’s position as slightly better, but his pieces are too tied up to exploit the extra pawn. To demonstrate the point, I’ll show how to deal with the engine’s first line for White: 25.Ra4 Bd7 26.Ra2 Bb5 26...h5!? 27.h3 Rxc4! 28.bxc4 Qxc4 is a more direct route to equality. 27.Bxb5 Rxb5 28.Kb2 Rc5 29.Kb1 Rc3 30.Re1 Qb7 31.h4!? This was my attempted improvement. 31.Re4 R8c5 32.Rd4 Qb5 33.Qe1 Kg7 34.Rd2 was Nightingale-Rook, email 2012, but Gawain Jones already noticed in his GM Repertoire book that 34...Qb7! makes it hard for White to make progress. That’s a correct assessment – we should not be fooled by the computer’s optimistic assessment for White. 31...R8c5 32.h5 gxh5 33.Rd1 I was hoping White would have some pressure with Black’s king opened up, but after the accurate 33...Rc8! 34.Rh1 Qb6= White is unable to make progress. Richter-Rauzer without 8...Bd7 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 6...Bd7 7.Qd2 Rc8 8.f4 was the DTS09 and Negi recommendation, but I show that 8.0-0-0 is just as good in Chapter 13. 7.Qd2 7...Be7 7...a6 8.0-0-0 h6 9.Nxc6 bxc6 10.Bf4 d5 11.Qe3 Bb4 12.a3 is the Negi/DTS09 recommendation, and a good alternative to my 12.Be2. Black’s best line seems to be 12...Ba5 13.h4 0-0 14.f3 (this Negi novelty has since been played in GM practice) 14...Nd7 15.Bd6 Re8 16.Na4 Nb6 17.Nxb6 Bxb6 18.Qf4 (18.Bc5!?) 18...Ra7N 19.Kb1 a5 20.g4 Bc7! 21.Bxc7 Qxc7 22.Qe3 Bd7 23.g5 h5 24.g6 fxg6 25.Rg1 Rb7 26.Rxg6 Reb8 27.b3 a4 28.b4 c5 29.Ba6 Be8 30.Rxe6 cxb4 31.Bxb7 Qxb7 32.Ka1 Bf7 33.Re5 bxa3 34.Qxa3 Qc7 35.Rg5 Qxc2=, but this is a bit of a computer line and if Black deviates at any point he ends up quite a bit worse. 8.0-0-0 0-0 9.f4 This is Negi’s line, but he recommends different follow-ups. 9.f3 was the DTS09 recommendation, but 9...a6 10.h4 Nxd4 11.Qxd4 b5 12.Kb1 Bb7 doesn’t offer White anything. For example: 13.Qd2 Rc8 (13...d5!?=) 14.Bd3 Nd7 15.a3 Ne5 16.Be2 f6 17.Bf4 Qc7 18.h5 h6= 9...Nxd4 10.Qxd4 h6 10...Qa5 11.Be2 is Negi’s recommendation, which has scored well in the latest games. 11.Bh4 Qa5 12.Bc4 e5 13.fxe5 dxe5 14.Qd3 Negi rightly shows that White has a positional advantage, so this can be a good alternative to my advocated ‘meet ...h7h6 with h2-h4’ approach. Richter-Rauzer 8...Bd7 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f4 This is Negi’s recommendation, but as happens with every opening book, improvements have since been found. 9.f3 Be7 10.h4 was the DTS09 recommendation, but since I have been unable to conclusively prove an outright advantage for White, I have also covered 10.Kb1. 9...b5 10.Bxf6 gxf6 11.Kb1 Qb6 12.Nxc6 12.Nce2!? is probably where White should look for an advantage, though the usual disclaimer that the engine tends to overestimate White’s position applies. 12...Bxc6 13.f5 b4 14.Ne2 e5 15.Ng3 h5 16.h4 Bh6 17.Qxd6 Rd8 18.Qxd8+ Qxd8 19.Rxd8+ Kxd8 20.Bxa6 Ke7 21.Rh3 Rg8 22.Bd3 The engines initially favour White’s chances, but as the theoretician Karsten Müller proved in the ‘Your Move’ section of New In Chess Magazine 2016/3, 22...Be3! gives Black sufficient activity to draw, an assessment confirmed by Negi himself. Najdorf 5...a6 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 This was the recommendation of DST09, but there were certain problem lines that made it impossible to give the English Attack approach my honest recommendation. My main recommendation 6.h3 was previously recommended in Modernized: The Open Sicilian, but has seen multitudinous developments since, as I show in Chapter 15. 6.Be2 has generally not been recommended in White repertoire books, but in my view, it’s a good way to ask some questions when you feel your opponent is better prepared than you in the complicated variations. 6.Bg5 was the sole subject of Negi’s Grandmaster Repertoire: 1.e4 vs. the Sicilian I: 6...e6 7.f4 Theoretically Black seems to be fine by playing 7...h6 8.Bh4 Qb6 and following the recommendations in the Yearbook 122 and 123 Surveys by Pijpers and Olthof respectively, but deep knowledge is obviously required by both sides. 6.f3 is covered under 6.Be3 Ng4 7.Bc1 Nf6 8.f3. 6...Ng4! This is the main trend at the highest level, where a draw with black is a fine result. 7.Bc1 7.Bg5 h6 8.Bh4 g5 9.Bg3 Bg7 I have been unable to find the slightest edge for White here, and furthermore Black has a plus score in recent top GM games: A) 10.Qd2 Nc6 11.Nb3 b5 12.h4 b4! was shown to be completely fine for Black in a couple of Vachier-Lagrave games; B) 10.Be2 h5 11.Bxg4 hxg4 is likewise harmless; C) 10.h3 Ne5 and now: C1) 11.Nf5 was the variation given in DTS09, but here it is sufficient to show one game: 11...Bxf5 12.exf5 Nbc6 13.Nd5 e6 14.fxe6 fxe6 15.Ne3 Qa5+ 16.c3 Nf3+ 17.Qxf3 Bxc3+ 18.Kd1 Qa4+ 19.Nc2 Bxb2 20.Rc1 Rc8 21.Bd3 Rf8 22.Qh5+ Ke7 23.Qxh6 Bxc1 24.Re1 Ne5 25.Rxe5 dxe5 26.Kxc1 Qa3+ 27.Kd2 Rxc2+ 28.Bxc2 Qb4+ 29.Ke2 Qb5+ 30.Ke1 Qb4+ 31.Kf1 Qc4+ 32.Kg1 Qxc2 33.Qxg5+ Kf7 34.Qxe5 Qd1+ 35.Kh2 Qd5 36.Qc7+ (Nakamura-Grischuk, Sharjah 2017) 36...Kg6! 37.Be5 Rxf2 38.Qg7+ Kf5 39.Qf6+ Ke4 40.Qxf2 Qxe5+ 41.g3 b5 and the endgame is a draw with normal play. White’s alternatives also lead to a 0.00 assessment; C2) 11.Qd2!? Nbc6 12.0-0-0 Nxd4 13.Qxd4 Be6 14.Nd5 has been tested regularly in correspondence, but doesn’t seem to give any advantage; one good antidote is 14...Rc8 15.c3 (15.Kb1?! 0-0 16.Qe3 Bxd5 17.Rxd5 Nd7! 18.h4 Qb6 19.Qxb6 Nxb6 even favours Black, as reflected in his heavy plus score in correspondence) 15...0-0 16.Qe3 Bxd5 (or 16...Nd7) 17.Rxd5 b5 18.Kb1 Nc4 19.Bxc4 Rxc4 20.a3 Qd7 and two games of the correspondence player Bars showed that White has nothing; C3) 11.f3 Nbc6 12.Bf2 Be6 13.Qd2 Rc8 14.0-0-0 Nxd4 15.Bxd4 Qa5 16.a3 (16.Kb1 Rxc3 17.Qxc3 Qxa2+ 18.Kc1 0-0 19.Qa3 Qxa3 20.bxa3 h5 gave Black full compensation for the exchange in Wunderlich-Hall, email 2012) 16...0-0 17.h4 g4 18.Qe3 Nc4 19.Bxc4 Rxc4= All the correspondence games were drawn (most quite quickly) from this point. 7...Nf6 Of course, White could repeat with 8.Be3 if he’s happy with a draw. 7...Nc6 8.Be2 Nf6 9.Be3 would move order Black into a promising line of the 6.Be2 repertoire. 8.f3 I was unable to find anything in the ...e7-e6 English Attack for White – hence I recommended other ways to prepare the kingside pawn storm: 8...e6! 8...e5 9.Nb3 Be6 10.Be3 is the main battleground at the time of writing, but I’m somewhat happy with White’s chances: A) In the old main line 10...Be7 11.Qd2 0-0 12.0-0-0 Nbd7 13.g4 b5 White has a lot of different options, but the current trend is 14.g5 b4 (I think 14...Nh5!? is the best move at the time of writing) 15.gxf6!? bxc3 16.Qxc3 Nxf6 17.Na5 Rc8 18.Nc6 Qe8 19.Nxe7+ Qxe7 20.Qa5², where White can fight for an edge without needing to memorise too many concrete lines. One could start by studying the games Van der Hoeven-Papenin, email 2012 and Giri-Vachier-Lagrave, St Louis 2016; B) 10...h5 11.Qd2 Nbd7 12.Nd5! (the 12.a4 suggestion of the previous edition has been proven innocuous in practice) 12...Bxd5 13.exd5 g6 14.Be2 Bg7 15.0-0= Extensive correspondence and engine practice suggest that the engines overvalue White’s extra space and bishop pair, and that the position is equal, but Black must be accurate to prove equality and can’t just rely on spacebarring. 9.Be3 b5 10.Qd2 Nbd7 11.g4 h6 12.0-0-0 12.a3 Bb7 13.0-0-0 Rc8 14.h4 d5 15.Rg1 dxe4 16.g5 hxg5 17.hxg5 Nd5 18.Nxe4 g6! 19.Kb1 b4 20.axb4 Bxb4 21.c3 Nxe3 22.Qxe3 Be7= was soon drawn in Burg-Figlio, email 2014. 12...b4 13.Nce2 Qc7! Back when DTS09 was published, this pawn sacrifice was only well-known in the correspondence/engine chess world. 14.h4 14.Qxb4 d5 15.Qc3 Bc5!? gives Black fantastic play for the pawn. 14...d5 I have been unable to find the slightest of edges for White, as this line has virtually been worked out to a forced draw by the computers. The recent Vesely-Burg, email 2017, is quite indicative: 15.Bf4 e5 16.Bh2 dxe4 17.g5 hxg5 18.hxg5 Rxh2 19.Rxh2 exd4 20.Rh4 20.Rh8 Nd5 21.Qxd4 Bb7 22.fxe4 N5b6 23.Qxb4 0-0-0= has been all draws in correspondence. 20...Ng4! 21.Rxg4 Nc5 22.Rh4 d3 23.Nd4 Bb7 24.Rh8 0-0-0 25.fxe4 25.Kb1 dxc2+ 26.Qxc2 exf3 27.Qd2 Be4+ 28.Ka1 a5 was soon drawn in Achilles-Kazantsev, email 2014. Note that 29.Bc4 Kb7 30.Qe3 Kb6! 31.g6 Bxg6 32.Qxf3 a4 doesn’t give White any advantage – I realise some of these moves look weird, but they are the best according to the computers at extremely high depths, with a 0.00 evaluation. 25...Bxe4 26.Qf2 a5 27.Rd2 a4 28.Bg2 g6 29.Qe3 b3 30.axb3 axb3 31.Rxf8 Qa5! 32.Rxd8+ Kxd8 33.Nc6+ Bxc6 34.Rxd3+ Nxd3+ 35.Qxd3+ Bd7= And the game was soon drawn. Congratulations on making it to the end of the book – you read it cover-to-cover, right? Index of variations Numbers refer to pages 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 2...h6 17 2...Qc7 17 2...b6 17 2...g6 18 2...a6 18 2...Nf6 3.Nc3 d5 4.exd5 19 4.Bb5+ Bd7 5.e5 334 2...Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 4...Nxd4 26 4...d5 26 4...d6 5.c4 26 4...Qb6 5.Nb3 Nf6 6.Nc3 e6 7.a3 Qc7 27 7...Be7 335 4...e5 5.Nb5 5...a6 6.Nd6+ Bxd6 7.Qxd6 Qf6 8.Qd1 35 8.Qxf6 337 8.Qc7 337 7...Qe7 36 5...d6 6.N1c3 a6 7.Na3 Nf6 41 7...Be6 41 7...b5 41 7...Be7 43, 338 4...g6 5.c4 Bh6 50 5...d6 6.Nc3 transposes 50 5...Nf6 6.Nc3 d6 50 5...Bg7 6.Be3 Nh6 53 6...Qb6 7.Nb3 Qd8 53 6...d6 7.Nc3 Qb6 54 6...Nf6 7.Nc3 d6 54 7...Ng4 54 7...0-0 8.Be2 55 5.Nc3 Bg7 6.Be3 Nf6 7.Bc4 0-0 8.Bb3 338 4...Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 6.Ndb5 d6 7.Bg5 a6 8.Na3 8...Be6 9.Bc4 73 8...b5 9.Nd5 Be6 73 9...Qa5+ 74 9...Be7 10.Bxf6 Bxf6 11.c3 Be6 74 11...Rb8 74 11...Bb7 74 11...Ne7 74 11...0-0 75 11...Bg5 12.Nc2 Ne7 77 12...0-0 78 12...Rb8 79 9.Bxf6 gxf6 10.Nd5 339 2...e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 4...Bc5 5.Be3 100 5.Nb5 101 4...Qb6 5.Be3 102 4...Nf6 5.Nc3 Qb6 6.e5 Bc5 7.Ndb5 104 5...Bb4 6.e5 104 5...Nc6 6.Ndb5 107, 345 6.Nxc6 345 4...Nc6 5.Nc3 a6 122 5...Qc7 6.Be3 a6 7.Qf3 Ba3 124 7...Nge7 8.Nb3 124 7...Bb4 8.Qg3 124 7...b5 8.Qg3 124 7...Ne5 8.Qg3 h5 125 7...d6 8.Nxc6 126 7...Bd6 8.0-0-0 Be5 127 7...Nf6 8.0-0-0 130, 349 7.Qd2 348 4...a6 5.Nc3 Bc5 143 5...d6 143 5...b5 6.Bd3 Ne7 144 6...Bc5 144 6...d6 145 6...Bb7 145 6...Qb6 148 5.Bd3 346 5.Nc3 Qc7 6.Bd3 6...Bb4 159 6...Ne7 159 6...g6 159 6...Bd6 159 6...Nf6 7.f4 Bb4 160 7.0-0 Bb4 161 7...h5 161 7...Bd6 161 7...b5 161 7...Nc6 162 7...Be7 163 7...d6 166 7...Bc5 170 2...d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 h6 6.Be3 e5 7.Bb5+ 187 5...Nbd7 6.g4 188 5...Bd7 6.f3 188 6.Bg5 351 6.Be3 351 5.f3 351 5.Nc3 e6 6.Be3 Nc6 (by transposition) 196 6.g4 e5 197 6...d5 198 6...h6 198 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 6...Ng4 203 6...a6 203 6...Bg7 7.f3 a6 203 7...Nc6 8.Qd2 Bd7 205 8...0-0 9.0-0-0 Qa5 206 9...Be6 206 9...Bd7 207 9...Nxd4 207 9...d5 10.Qe1 209 9.Bc4 353 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 6...h6 223 6...e5 223 6...Qa5 223 6...Qb6 223 6...a6 224 6...Bd7 7.Qd2 a6 224 7...h6 224 7...Nxd4 8.Qxd4 Qa5 225 7...Rc8 225 6...e6 7.Qd2 Bd7 226 7...h6 226 7...Qb6 227 7...Be7 228, 354 7...a6 8.0-0-0 Nxd4 231 8...Be7 231 8...h6 232 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 Bd7 9.f3 9...Nxd4 249 9...Qa5 249 9...Qc7 250 9...Rc8 250 9...b5 250 9...h6 10.Be3 Nxd4 251 10...h5 251 10...Rc8 251 10...Be7 251 10...Qc7 251 9...Be7 10.h4 Nxd4 253 10...0-0 253 10...Qc7 253 10...h6 11.Be3 h5 254 10.Kb1 255 10...Nxd4 255 10...0-0 255 10...Rc8 256 10...b5 256 10...Qc7 257 5.Nc3 a6 6.h3 6...h5 268 6...b5 268 6...Nc6 268 6...g6 269 6...e5 7.Nde2 Be7 270 7...Be6 270 7...b5 271 7...h5 272 6...e6 7.g4 b5 277 7...d5 279 7...Nfd7 281 7...h6 283 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be2 6...Qc7 312 6...b5 312 6...Nc6 312 6...Nbd7 313 6...g6 313 6...e5 7.Nf3 Be6 314 7...Qc7 314 7...h6 314 7...Be7 314 6...e6 7.Be3 b5 315 7...Nbd7 316 7...Nc6 316 7...Qc7 316 7...Be7 317 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 Ng4 356 Index of players Numbers refer to pages A Adams 182 Akopian 32, 308 Alsina Leal 86 Anand 92, 98, 292, 295, 296, 310 Andersen 39 Annaberdiyev 323 Ardelean 330 Areshchenko 297 Artemiev 178 Atlas 200 B Bai 133 Bajt 260 Baranowski 82 Becker 191 Bednar 239 Belak 246 Benko 61 Bennborn 93 Berg 116, 191 Biedermann 290 Bittencourt 116 Blomqvist 304 Bobras 133 Boccia 261 Bogner 138 Bok 135, 136, 184 Bokros 69 Branding 244 Bresadola 217 Brunsek 61 Bryzgalin 30 Bui 174 Bu Xiangzhi 236 C Cantelli 291 Cardoso Garcia 239 Carlsen 71, 91, 174, 298, 324 Carstensen 294 Caruana 139, 174, 287 Cerrato 333 Cerveny 331 Chizhikov 63 Chocenka 99 Cholo Banawa 62 Ciesielski 309 Craciunescu 93 D Danner 242 Dauga 182 Daurelle 267 De Blasio 214 Dembo 301 Dietrich 329 Ding Liren 236 Doderer 137 Dolgov 25 Dominguez Perez 47 Dunlop 86 Dzenis 245 E Ehlvest 118 El Gindy 47 Eremin 264 Esen 85 Evtushenko 305 F Fagerström 245 Feldborg 303 Fenes 25 Fier 142 Filip 186 Finegold 66 Fischer 214 Flumbort 332 Fressinet 67 G Gähwiler 235 Galojan 68 Ganguly 96, 222 Ganin 216 Gaysin 247 Gburek 333 Gelfand 298, 309 Gerasimov 247, 325 Gerhards 299 Giri 95, 213 Gleyzer 218 Goh Wei Ming 213 Gomila Marti 330 Gopal 191 Grachev 134, 153 Grischuk 134, 176, 307 H Hamdouchi 67 Hansen 294 Hebels 99 Henderson 65 Hess 219 Hirneise 241 Holzke 70 Horvat 300 Hou Yifan 242 Hovhannisyan 324 Huerga Leache 259 I Ikonnikov 48 Iotov 194 Istratescu 48 Iturrizaga Bonelli 82 Ivanchuk 175, 200 Ivanisevic 213 Ivanov 246 J Jacobsen 115 Jakubowski 331 Jarabinsky 239 Jensen 244, 291 Joppich 217 Jumabayev 141, 240 K Kamber 190 Kamsky 180 Karacsony 235 Karjakin 87, 90, 287 Karpov 67 Kempinski 67, 289 Khamrakulov 133 Khromov 154 Kokarev 32 Konovalov 45 Kozul 264 Krause 137 Krivtsov 264 Kryvoruchko 82, 185 Krzyzanwski 265 Kudrin 84 Kuhne 115 Külaots 307 Kurnosov 121 Kuzmin 69 Kveinys 174 L Lauth Oliveira 89 Lazarev 141 Leal 157 Leenhouts 136, 142 Leko 91, 94, 221 Lie 71 Liiva 119 Lim Yee Weng 218 Lindberg 201 Li Shilong 179 Lobanov 302 Locio 216 Lokander 201 Lopez Martinez 133 Luch 179 Lugovskoy 141 M Mamedyarov 180 Ma Qun 179 Martorell Aubanell 86 Masarik 83 Matsuura 259 Mazur 239 Mekhitarian 259 Melkumyan 293 Miciak 246 Mignon 301 Minasian 85 Moll 235 Monreal Godina 330 Moreira 303 Motylev 120 Movsesian 140, 242, 308 Müller Alves 91, 267 Myakutin 89 N Nagy 191 Najer 178 Nakamura 23, 175 Nasuta 304 Neelotpal 264 Nepomniachtchi 295, 307 Neverov 155 Nickel 220 Nijboer 184 Nimtz 192 Noble 236, 247, 305 Novak 194, 247 O Ochoa Aldaz 45 Ochoa de Echaguen 84 Ortin Blanco 45 P Panchenko 23 Panyushkin 290 Parushev 266 Pengxiang 120 Percze 88 Perez 246 Pert 215 Petkov 266 Petrosian. 68 Pfleger 64 Pijpers 155 Pinter 69 Pirs 237 Pogosyan 45 Polugaevsky 63 Popov 141 Portisch 64 Prasanna 138 Pruijssers 215 Psakhis 23 Q Quattrocchi 217 Quintiliano Pinto 222 R Radjabov 90, 92, 94, 288 Raghunandan 293 Raijmaekers 328 Raivio 88 Ramirez 261 Raznikov 307 Ringdal Hansen 32, 241 Robson 295, 325 Romero Holmes 118 Rook 220 Rosche 328, 329 Ruano Lopez 236 Rublevsky 30, 139, 327 Rud Ottesen 303 Rui Gao 183 Rytshagov 119 S Sadvakasov 240 Saleh Salem 297 Sanchez 259 Saric 193 Sasikiran 263 Sax 213 Schakel 157 Schiendorfer 156 Schnabel 300 Schuller 65, 86 Secrieru 118 Sekretaryov 237, 302 Serazeev 301 Sevian 62, 63 Shabalov 262 Shengelia 242 Shirov 87, 95, 96, 193, 309 Silva Lopes 303 Simacek 38 Skrobek 309 Smeets 66 Smirin 185, 288 Smuts 295 So 263 Solak 323 Soltau 192 Soumya 262 Spirin 219 Spoelman 135 Sprenger 179 Staniszewski 322 Stanojevic 34 Studer 235 Suetin 63 Sutela 214 Svidler 327 Swiercz 289 Szabo 332 T Taboada 91 Tari 140 Temirbayev 121 Ter Sahakyan 153, 324 Timofeev 176 Tochacek 34 Tolstikh 69 Topalov 292, 296 Trent 221 Tseshkovsky 322 V Vachier-Lagrave 310, 324 Van de Ploeg 218 Van Wely 98, 200 Vlcek 301 Voiculescu 156 Volkov 154 Voll 39 Vorobiov 190 Vovk,A. 330 Vuckovic 70 W Wagner 200 Walsh 244 Walter 299 Wei Yi 24 Westerberg 116 Wilson Rocha 116 Winkler 214 Wojtkiewicz 23 Wölfl 118 Wosch 265 Y Yan Fang 24 Yanushevsky 260 Yu Yangyi 60 Z Zadruzny 32 Zakharov 83 Zhang Ziyang 218 Zhou Jianchao 183 Zinchenko 186 Zlotkowski 82, 217 Zmokly 244 Zvjaginsev 60 Zwardon 38