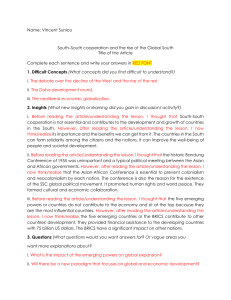

514191 research-article2013 JAS0010.1177/0021909613514191Journal of Asian and African StudiesWasserman JAAS Article South Africa and China as BRICS Partners: Media Perspectives on Geopolitical Shifts Journal of Asian and African Studies 2015, Vol. 50(1) 109­–123 © The Author(s) 2013 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0021909613514191 jas.sagepub.com Herman Wasserman School of Journalism and Media Studies, Rhodes University, South Africa Abstract The emergence of the Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) group of states as a new geopolitical power bloc has received substantial coverage in the media. South Africa’s inclusion in the group has been particularly controversial, and media attention tended to focus on the country’s relationship with China against the backdrop of the BRICS alignment. The media industry itself has also been a part of global movements of people and capital. This article seeks to establish how this relationship has been represented in the South African media, and to explore the attitudes of senior journalists and editors towards South Africa’s position within the changing global geopolitical landscape. Keywords Africa, BRICS, China, geopolitics, journalism, media, South Africa Introduction The emergence of new regional centres in Asia, Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, acting as nodes for increased transnational flows of media content and capital, have called for more comparative work about media within and across regions of the Global South. An understanding of how the geopolitical shifts associated with the emergence of regions outside of the old Euro-American centres of power – the ‘rise of the rest’ (Zakaria, 2011: 2) – are impacting global communication patterns, demands more comparative studies of countries such as Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – the so-called BRICS alignment of emerging economies. The formal invitation extended to South Africa by China late in 2010 to join the BRIC formation of emerging economies (Brazil, Russia, India and China) can be seen as a confirmation of the growing economic ties between China and South Africa. When South Africa’s membership of the BRICS formation is discussed, the focus therefore often falls on the country’s relationship with China. Corresponding author: Herman Wasserman, School of Journalism and Media Studies, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, 6139, South Africa. Email: h.wasserman@ru.ac.za Downloaded from jas.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 12, 2016 110 Journal of Asian and African Studies 50(1) The expanded trade between these two countries has been welcomed as an opportunity for South Africa to meet its development needs. For China, the interest in South Africa as an emerging market forms part of its growing interest in Africa for resources, markets and diplomatic support. However, this involvement has not been unequivocally welcomed. While for some China’s growing concern in Africa is seen as an opportunity for the continent to grow its economies and become a stronger presence in international markets, others are concerned that the economic boost that China brings to the African continent comes with too high a price tag. Concerns raised include controversies around China’s commitment to human rights and press freedom, which critics see as posing a bad example for African countries. China’s support for corrupt African leaders in undemocratic regimes, tough labour practices and the loss of local jobs to Chinese migrant workers has been further cause for concern. Some of these critics go as far as to say that the increased involvement of the BRICS countries in Africa, with China the strongest among them, constitutes a new type of imperialism and a ‘scramble for Africa’ (Taylor, 2013). Zeleza (2008) identified three tropes in the discourses about China’s presence in Africa as a whole as being in terms of imperialism, globalization or solidarity. Pieterse (2009) similarly sees certain key themes in the way the ‘rise of the rest’ has been reported – the geopolitical shifts are either ignored, represented as a threat or celebrated in business media as a triumph for capitalism. To these categories, one could add an Orientalist narrative. In this narrative, China is either presented as a threatening Other, such as the ‘yellow peril’, or the evil Dr Fu Manchu, the evil genius or super-villain set on undermining the West to achieve global domination (Sautman and Hairong, 2007), or as a mysterious, exotic and unknowable force, as an ‘ominous dragon’ that has to be ‘fed’ with African minerals (e.g. Daly, 2009). This article considers the role that the media plays in representing the relationship between China and South Africa within the context of their co-membership of the BRICS formation of emerging states. Firstly, a brief background to the growing relationship between these countries and the geopolitical shifts marked by the formation of the BRICS group will be given, with a focus on the way that these developments are increasingly being played out via media coverage and investment in media capital. The article then considers findings from recent content analyses on the coverage of China in South African media to discern patterns of coverage that have evolved during recent years. In conclusion, the content analysis is complemented by comments from editors and senior journalists at South African media to provide an insight into how the coverage of the China– South Africa relationship, within the context of the BRICS formation, is shaped by journalistic attitudes and practices. South Africa and China within the context of BRICS South Africa’s hosting of the summit of the BRICS countries, held in Durban from 26 to 27 March 2013, provided it with an opportunity to project itself as the economic leader on the African continent and to capitalize on its association with a prestigious club of emerging economic powers. South Africa was intent on positioning itself as a leader on the African continent and insisted on a stronger focus on Africa in discussions among the BRICS nations, for instance around the establishment of a proposed BRICS development bank (Fabricius, 2013). The summit also coincided with the state visit of president Xi Jinping to various African countries (Tanzania, South Africa and the Republic of Congo), which has been seen as underscoring the strategic importance of China’s relationship with Africa. Ahead of his visit, Xi emphasized the value that China sees in its ‘friendly relationships with all African countries, no matter whether they are big or small, strong or weak, rich or poor’ (Olsen, 2013). Xi’s visit to South Africa during the summit provided the opportunity for South Africa and China to cement their relationship: a number of bilateral agreements Downloaded from jas.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 12, 2016 111 Wasserman concerning international relations, environmental affairs, education and economic development were signed, a joint interministerial working group on South Africa–China cooperation established and proposals made to herald 2014 as the year of South Africa in China and 2015 as the year of China in South Africa to deepen the relations between these two countries even further (Bauer, 2013). Although big international events such as this summit provide a strategic platform to boost the country’s international image, the summit received the usual share of criticism about its unjustified cost, considering the many other pressing needs in the country. In the run-up to the summit it was reported that hosting the event would cost the city of Durban’s ratepayers an estimated R10 million (approximately USD 1.08 million) (Padayachee et al., 2013). These costs included banners, flags and branding material to impress visitors to the city. The counterargument to critics of expenses to showcase South Africa’s inclusion in the BRICS group include the minister of International Relations and Co-operation, Maite Nkoana-Mashabane, under whose tenure the country acceded to the BRICS group. Nkoana-Mashabane is on record (2012) as saying that the country’s membership of BRICS is a foundation not only for its own growth, but also for economic regeneration of the continent as a whole. However, despite the opportunity the summit provided for South Africa to bask in the glory of its partners in an economic alignment that signals major shifts in geopolitical power, its membership of the BRICS club, and the BRICS alignment itself, is not without controversy. Critics have pointed to the fact that South Africa’s economy is tiny in comparison with other BRICS partners, especially that of China. Despite being the economic leader on the continent, some argue that countries such as Mexico, Indonesia, South Korea and Turkey would be more deserving of a place in a group of emerging economies than South Africa (Roughneen, 2011). Furthermore, the huge internal inequalities in South Africa militate against a hasty celebration of its economic growth path and sustainability. Ahead of the BRICS summit in Durban, some observers (Mnyandu, 2013) already forecast that the summit would be unlikely to provide any tangible outcomes to improve South Africa’s economic sustainability. The BRICS alignment itself has also been viewed with scepticism. It has been said (Bremmer, 2012) that the most enduring aspect of the BRICS alignment is the ‘catchy acronym’ itself. This criticism is based on the disparities in economic size and growth between the partners, the vast differences in their political and economic systems, and the frictions within this group that are seen as likely to increase rather than go away. Notwithstanding the criticism of the group as a construction based on a desire to forge links and mask differences between the member countries, the emergence of this group as a strategic partnership is likely to have far-reaching implications for Africa in general and South Africa in particular. On the positive side, its membership of BRICS holds the potential for South Africa to contribute to the formation of the planned BRICS Development Bank and leverage investments for development. On the negative side, the interaction of the BRICS countries with South Africa and other countries on the continent may free Africa from older, post-colonial relationships with Europe and the United States, but if appropriate development policies are not developed, the continent’s dependency on external powers may just be diversified rather than improved (Taylor, 2013). Of the relationships between South Africa and its BRICS partners, the relationship with China has been the most controversial. As will be discussed later in more detail, this relationship is an increasingly mediated one, and calls for an analysis of the way that the media emerges as an actor in the shifting geopolitical relationships as exemplified by the BRICS formation. Such an analysis would benefit from a brief historical contextualization of this growing relationship, against the background of other China–Africa engagements, so as to recognize ‘the complexities, contradictions, and changing dynamics of Africa’s age-old engagements with China’ (Zeleza, 2008: 171). Downloaded from jas.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 12, 2016 112 Journal of Asian and African Studies 50(1) Background1 The first instance of ‘Sino-African contact’ can be traced back to 1415, when Admiral Zheng visited more than 30 countries in Africa (Waldron, 2009: 4). Official relations between Africa and China in contemporary times started in 1955 with the first Asian-African Conference in Bandung, Indonesia, aimed at promoting economic and cultural cooperation (Le Pere and Shelton, 2007: 69). A proliferation of Sino-African diplomatic agreements took place in the 1950s and 1960s, the first of these being an agreement in 1956 between China and Egypt. This was followed in later years by diplomatic ties between China and several African countries (Waldron, 2009: 6–10). As the Cultural Revolution gained momentum (1966–1976), official ties between China and these countries were severed as China withdrew from foreign commitments and recalled its ambassadors from African countries (with the exception of Egypt; Le Pere and Shelton, 2007: 58; Waldron, 2009: 10–13). Economic ties remained, however, and in the 1970s China funded several large infrastructural projects in Africa, including the famous Tanzania–Zambia (Tan-Zam or TAZARA) Railroad from 1970 to 1977, as well as 75% of the military aid given to the African Union. The relationship between China and Africa has therefore been ‘episodic’, ranging from ‘intense activity’ in the 1960s and 1970s to neglect in the 1980s (Alden, 2007: 9). The development of China–Africa relations in the 21st century gained impetus in the 1990s. It had become clear that to maintain the ‘roaring pace’ of its economic growth as a result of economic reforms, China would need to look for new sources of energy and natural resources to feed its ‘seemingly insatiable appetite for energy resources’ (Daly, 2009: 78), which it found in Africa (Alden, 2007: 11–12). By the mid-2000s, over 800 Chinese companies were trading in 49 African countries, resulting in a steep rise in trade (Alden, 2007: 14). In 2010, China became the continent’s largest trade partner, making up 10.4% of Africa’s total trade (Buthelezi, 2011). This trade has increased tenfold in the decade between 2000 and 2010 – compared to the eightfold increase in trade with the rest of the world – and outperformed the rapid boom in gross domestic product in China. China’s interest in Africa has not only been motivated by economic concerns, but it has also extended into the political and military arenas as China looked for partners in the developing world that could strengthen its position in the face of economic sanctions and political attacks after crackdowns on pro-democracy protests in the 1990s (Zheng, 2010). This intensified political-economic relationship in the era of globalization and within a changing global geopolitical landscape started to raise questions as to how China’s renewed interest in Africa should be viewed. These concerns included whether China should be seen as a ‘partner or predator’, the consequences of the tension between the US and China over mutual interests in Africa (Mills and Thompson, 2009: 56), China’s support for corrupt African leaders in undemocratic regimes, Chinese companies’ harsh labour practices, and the importation of Chinese labour to the exclusion of local workers (Sautman and Hairong, 2007). Most recently, a debate has ensued with regard to China’s influence on press freedom on the continent (Keita, 2012). While South Africa’s relationship with China can be understood as part of both South Africa’s global repositioning in the post-apartheid era and the country’s emergence as a regional power, it should be seen as part of a longer history of Sino-African relations, as well as a sign of shifting geopolitical interests in the current moment. China’s role in post-apartheid South Africa is therefore not a straightforward one, but marked by historical legacies and contemporary political-economic power relations. Whether viewed as a positive engagement or a negative impact, the size and impact of this engagement cannot be ignored. It can be assumed that the relationship between these two countries would enjoy significant media coverage. The question is how this relationship would be portrayed. Downloaded from jas.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 12, 2016 113 Wasserman Media and soft power Western reportage about China’s involvement in Africa has often been characterized by fearmongering or a paternalism that emphasizes the threat China poses to African countries, often drawing on Orientalist tropes (Daly, 2009; Sautman and Hairong, 2007; Wasserman, 2012). Attempts to counterbalance these discourses of imperialism often make use of an equally simplistic frame of solidarity (Zeleza, 2008). In South Africa, contesting views of China can be found in the media. Just how divergent these views can be, was highlighted by a recent public spat between the investigative magazine Noseweek and an online news site Daily Maverick. Noseweek published a report titled ‘Howzit [hello] China’ (http://www.noseweek.co.za/article/2836/Howzit-China) that engaged in rather crude stereotyping and generalization of Chinese shopkeepers in South Africa. It argued that Chinese shops have ‘popped up’ in every town of South Africa and amount to a ‘largely unlawful enterprise that threatens to destroy local commerce and cost the taxman billions’. The argument is a familiar xenophobic one: foreigners are here to steal our jobs, Chinese are dishonest and are smuggling their way into the country and defrauding our government of its due tax revenue. Soon after the Noseweek article appeared, journalists Kevin Bloom and Richard Poplak wrote a response in the online news site Daily Maverick (http://dailymaverick.co.za/article/2012-10-30-nosedive-chinese-shopkeepercover-story-a-new-low-for-south-african-journalism), pointing out the generalizations, factual errors and xenophobic stereotyping with which the Noseweek article is riddled. Calling the Noseweek article a ‘new low for South African journalism’, Bloom and Poplak draw on their own investigative fieldwork to counter the claims made in the Noseweek article. They also point towards the dangers of such xenophobic reporting – reminding readers of attacks on migrants in South Africa in recent years. Some observers (Plaut, 2012) have argued that China’s increased investment in media platforms in Africa may be seen as a way to counter the negative reporting and fearmongering of articles such as the one in Noseweek and to present a positive image of China to African audiences. Examples of China’s media presence on the continent include the launch of the state broadcaster, China Central Television (CCTV), with its African head office operation in Nairobi (Kenya) in 2010. This presence makes it possible for CCTV news reports to be broadcast across the continent. The state news agency Xinhua has been present on the continent since the 1980s, but in 2011 it also launched a mobile application that makes its news service available to the continent’s millions of African mobile phone users. Xinhua’s English channel CNC World is now also being broadcast to subscribers to the digital satellite television platform DStv, after the South Africa-based company MIH agreed to carry it on its African networks. On the print news front, the opening of bureaux in Johannesburg and Nairobi of the English-language edition of China Daily has extended the newspaper’s reach to English-language readers in these major African centres, as well as online. Exchange programmes for media groups and journalists to visit China and vice versa have also been seen as a way to further extend its cultural influence. In South Africa, the involvement of a Chinese group in the Sekunjalo consortium, that in 2013 bought the Independent group of newspapers, has received significant media attention. Anton Harber, prominent media academic and former newspaper editor, was one of the critics who raised reservations about what the Chinese involvement in the South African media landscape could mean for media freedom in the country. Harber worried that ‘the Chinese media culture is not going to sit easily in Africa where we have been developing and hopefully entrenching much more open democratic media culture, and expressed concern that ‘Chinese media investment and ownership brings a kind of top-down style of Chinese journalism and can inhibit the progress we have made in this continent developing an open bottom-up style of investigative journalism’ (Umejei and Hall, 2013). China earlier also Downloaded from jas.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 12, 2016 114 Journal of Asian and African Studies 50(1) invested in the digital television provider TopTV, a rival to the established platform Multichoice, in South Africa. Harber (2013) remarked on these Chinese investments in South African media: ‘That creaking sound you hear is the global see-saw tilting eastwards.’ But others in the South African media, notably the secretary-general of the South African National Editors’ Forum (SANEF), Hopewell Radebe, seem less concerned about the suggested deleterious influence of China on the South African media. Radebe is of the opinion that it will not be a danger to media independence: ‘if the Chinese invest in South African media, it will be business and nothing more than that’ (Umejei, 2013). The notion of ‘soft power’ (Nye, 2005) – defined as a means to achieve desired political outcomes by using influence and persuasion rather than force – has been applied to China’s involvement on the continent, and specifically its media interests in Africa. The extension of China’s international media reach not only by extending the Chinese media offerings abroad as mentioned above, but also by ‘professionalizing’ and ‘polishing’ international broadcasts of Chinese state television (CCTV), has been seen as part of such a global ‘charm offensive’ (Kurlantzick, 2007: 63) and a means to counter negative stereotyping and fearmongering in African media. Media flows between China and Africa have, however, not only been one-directional. The South African media company Naspers, for instance, has been benefiting greatly from its investment in the media platform Tencent in China, which now accounts for more than 80% of the media conglomerate’s R200 billion (approximately USD 25 billion ) market capitalization (Steyn, 2012). Naspers’s Chinese investment is therefore largely responsible for the repositioning of a media company that was built on Afrikaner capital during the apartheid era and was largely supportive of the apartheid regime, to become a global media conglomerate. From the above examples it becomes clear that media content as well as media capital are part of the flows and counterflows between Africa and China. The engagement between China and Africa, and China and South Africa more specifically as BRICS partners, is therefore also likely to play out in the media sphere. The media are likely to increasingly be a central space where battles for representation, struggles for perceptions and jostling for influence over audiences will take place. Research question and methods This article seeks to explore how China’s increasing involvement in the South African media sphere, against the background of South Africa’s membership of BRICS, is represented in the South African media. It further seeks to illuminate these media representations by exploring the views of journalists and editors of major media outlets with regard to South Africa’s position in the new geopolitical landscape signified by South Africa’s membership of BRICS, with particular reference to South Africa’s relationship with China. The first component of the study was to continue a content analysis of reports in major media on BRICS to build on a previous study (Wasserman, 2012). The previous study analysed the volume and tone of coverage of the BRICS alignment, and compared coverage of South Africa’s BRICS partners. That study was a response to literature about China’s role in Africa that had suggested that China’s presence on the continent was often represented in stark binary terms, as either an exploitative, predatory force or a benevolent development partner. The study found, however, that a more balanced view of China overall had been emerging in the South African media since 2009. While individual reports may, of course, still display xenophobic attitudes, for example the Noseweek article referred to above, the overall attitude towards BRICS in South African media could be described as one of ‘cautious optimism’. When considered on the whole and across a range of media platforms, the study found that China was not represented in either a starkly Downloaded from jas.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 12, 2016 115 Wasserman positive or starkly negative light. The overall balance in media reports during the period studied in that article (January–December 2010, and building on literature reporting on coverage during 2009) suggested an understanding that China’s role in Africa is a complex one that could not be pigeonholed as either a ‘bad’ or ‘good’ news story. The analysis concluded that South Africa’s association with China as a partner country in the BRICS formation might continue to shape positive coverage in the future, and therefore recommended that future studies continue to track developments in coverage. The current article builds on the findings reported by Wasserman (2012) by extending the period of coverage to a year and a quarter, that is, January 2011–March 2012. The method followed is similar to that used by Wasserman (2012).2 Data was generated by the media analysis organization Media Tenor by means of a computerized content analysis of major newspapers, TV news channels and radio stations (i.e. across all mainstream ‘traditional’ platforms, excluding the web). Reports mentioning China, Brazil, Russia and India were identified, and then evaluated and coded for their attitude towards the topic, in this case the countries in question. Coders, trained to code according to the criteria, were subject to bi-monthly validation tests, as well as weekly spot checks. For these weekly spot checks, a random analysed article was drawn. The trainer established a master copy of the said article and compared it to the sample drawn. Depending on the depth of the information, each article contained between 30 (standard) and 110 (extended) variables. An inter-coder reliability percentage of at least 80% was achieved. This percentage indicates the extent to which the variables correlated with the master copy. Bi-monthly validation tests were also conducted. In these tests, 10 articles were prepared and the trainer analysed all 10 articles. The coders then analysed the same articles. The results were measured against the master copy, as well as against each other to establish inter-coder reliability. The media outlets used for the analysis included broadcast as well as print media specializing in business coverage (as previous studies indicated that BRICS coverage was framed largely in economic terms): SABC (the public broadcaster), E-TV (free-toair, private broadcaster), Summit TV (business channel carried on private, subscription-based satellite television), Business Day, Business Report, Financial Mail, Business Times and Sake24. Results were broken down into coverage of the various BRICS partners, as well as coverage of China specifically. This content analysis aims to answer the first two research questions of this article: 1. 2. What was the volume and tone coverage of the BRICS countries in major South African media from January 2011 to March 2012? What was the volume and tone of the coverage of China in major South African media from January 2011 to March 2012? The second component of the study was aimed at establishing how editors and senior journalists working at South African media reported on their own perceptions of the BRICS alignment and South Africa’s place in it. The assumption underpinning this exploration of journalists’ and editors’ attitudes was not that a direct causal link can be traced between individual journalists’ attitudes and coverage in their media outlets. It is an accepted notion that a ‘hierarchy of influences’ (Reese, 2001) shape media content. Not only individual attitudes, but journalistic routines, organizational factors, extra-media influences and ideological perspectives all work together to determine media coverage (Reese, 2001: 179–183). Nevertheless, the ‘attitudes, training, and background’ of journalists are considered ‘influential’ in shaping media content, even as it is acknowledged that journalists should not be considered an undifferentiated group and that the sample of journalists be considered carefully when drawing conclusions about journalistic attitudes. Downloaded from jas.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 12, 2016 116 Journal of Asian and African Studies 50(1) For this study, a purposive sample of editors and senior journalists was selected based on two criteria: their employment at one of the major media outlets analysed in the two content analyses (Wasserman, 2012, and the current study), and their seniority in the organization, which is likely to amplify their influence over media content. The respondents represented major media outlets in print and broadcast: SABC, E-TV, CNBC Africa, City Press, Business Day, Mail & Guardian, The New Age, Business Report and Pretoria News. After initial contact was established via email or telephone, a qualitative online questionnaire was administered to the journalists and editors. Ten responses were gathered, providing qualitative answers to nine open-ended questions that first explored general attitudes towards South Africa’s position in the BRICS alignment before focusing more specifically on South Africa’s relationship with China as follows. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. What is your opinion about South Africa’s membership of the BRICS alignment of emerging economies – is it a positive or negative development? Which of the BRICS countries do you think are the most important to cover in your publication? Has your view of China’s involvement in South Africa changed or developed in recent years? What aspects about the relationship between South Africa and the BRICS countries do you think your readers/audience are most interested in? What in your opinion are the main benefits for the BRICS countries to form such an economic alliance? In your opinion, is this a partnership of equals, and if not, which partner is dominating? Which of the partners do you think will gain most from the alliance, and which the least? Have you participated in any exchange programmes with China or other BRICS countries, and if you have, how has this influenced your reporting of China? Do you use Chinese media sources, such as from Xinhua or CCTV? Why/why not? The limitations of such an online questionnaire are acknowledged, but the expectation of the study was not to gather conclusive or generalizable answers about journalistic attitudes, but rather to provide a qualitative complement to the quantitative content analysis, so as to highlight areas for further exploration and provide a basis for a more extensive investigation in the future. The questionnaire was aimed at answering the third research question of this study, namely: 3. What broad themes could be identified in the attitudes of journalists and editors towards South African’s membership of the BRICS alignment in general and its relationship to China specifically? Findings Research question 1 asked what the volume and tone of South African media coverage of the other BRICS countries looked like during the period of study. The content analysis displayed a clear dominance of China (Figure 1) in terms of the volume of coverage in the South African media from January 2011 to March 2012. Of the 555 reports that were analysed, 301 focused on China. Its closest competitor in terms of volume of coverage, India, received almost half the amount of coverage – 161 reports in total. Brazil was the topic of focus of 49 reports and Russia of 44 reports. This distribution of coverage is similar to the period July 2009–December 2010 reported on by Wasserman (2012), where China also dominated coverage followed by India. Downloaded from jas.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 12, 2016 117 Wasserman China India Brazil Russia 0 100 Negative 200 Neutral 300 400 Positive Figure1. BRIC profiles in South African media: January 2011–March 2012. As far as tone of coverage is concerned, reporting on all four South Africa’s BRICS partners was quite balanced. With the exception of Russia, which received more negative coverage (21 reports) than positive (7) or neutral (16) reports, the tone of most reports on China, India and Brazil was coded in the ‘neutral’ category. Reporting on China was evenly balanced, with 65 negative reports, 65 positive reports and 171 neutral. India received 22 negative reports, 52 positive and 87 neutral, while Brazil received 9 negative reports, 24 neutral and 16 positive. This analysis shows clearly that the South African media considers China to be the most important of the BRICS partners. When the coverage of China and India as the two most dominant BRICS countries is combined, it further confirms the trend reported on by Wasserman (2012) that ‘Chindia’ (Thussu, 2010) as a region is emerging as a focus point for the South African media, as this region is a bigger trade partner for South Africa than Brazil and/or Russia. The tone of the reports on most of the BRICS countries, specifically China, also continues the earlier trend of balanced views rather than a stark positive/negative binary discourse. Considering research question 2, on the volume and tone of the coverage of China specifically, Figure 2 indicates a dominance of business coverage when compared to more general news broadcasts (SABC and E-TV). This is a slight change from the previous study (Wasserman, 2012) of coverage in 2010, where SABC 3 news provided the most coverage of China. While the latest content analysis represented in Figure 2 seems to indicate that the interest in China is increasingly driven by business interests, this is not an unequivocal conclusion, as two business publications (Business Times and Financial Mail) are also found at the bottom of the list of media outlets in terms of the volume of their coverage. Further research into the content and focus of these reports will be required before more substantial conclusions can be drawn in this regard. As for the tone of the coverage of China during this period, the coverage was dominated by ‘neutral’ reports, thereby continuing the trend of ‘cautious optimism’ that marked the reporting on China over the past number of years (see Wasserman, 2012, for how this attitude played out in previous studies). Figure 3 shows the distribution of ‘positive’, ‘negative’ and ‘neutral’ reports on China. General news bulletins on broadcast media display a slightly higher proportion of positive reports. This could be as a result of the nature of broadcast news bulletins as more general and superficial in their approach, highlighting only new events and developments that may come across as more positive in tone, than the more in-depth and critical analyses offered by the business media, which would weigh up different positions and therefore be coded as neutral. This again is, Downloaded from jas.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 12, 2016 118 Journal of Asian and African Studies 50(1) Business Day Business Report SABC 3: News @ One Summit TV E-TV News Sake24 Afrikaans News (SABC2) English News (SABC3) Business Times Financial Mail 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 Number of reports Figure 2. Volume of reporting on China in South African media: January 2011–March 2012. Business Day Business Report SABC 3: News @ One Summit TV E-TV News Sake24 Afrikaans News (SABC2) English News (SABC3) Business Times Financial Mail 0% 20% 40% Negative 60% Neutral 80% 100% Positive Figure 3. Tone of South African media reports on China: January 2011–March 2012. however, speculation that would have to be borne out by a more qualitative analysis of the content and subject matter of the various reports. Journalists’ views The findings emerging from the online questionnaire sent to senior journalists and editors at influential South African media outlets to answer research question 3 (the attitudes of senior journalists Downloaded from jas.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 12, 2016 119 Wasserman and editors towards South Africa’s role in the BRICS grouping, and China in particular) resonate with the findings from the content analysis. Responses from the journalists and editors suggest a similar cautiously optimistic view of the BRICS alignment. A recurring theme in the responses is the view that South Africa’s inclusion in the BRICS alignment is a positive development, as it gives the country a seat at the ‘big table’ of emerging powers. The benefits from South Africa’s association with the group are seen mostly in economic terms. One journalist responded that ‘the creation of more trade opportunities is always positive’, while another saw BRICS as a ‘prestigious club to be a part of’. Editors are, however, not blind to the fact that South Africa does not ‘belong’ in the BRICS group on the strength of its economy. One respondent remarked: I think it (South Africa’s membership of BRICS) helps to ensure that South Africa is at the big table in major multilateral fora. In many ways I think we should be focusing more on middle-power diplomacy, and I am sympathetic to the argument that we don’t ‘belong’ in BRICS, but the aggregate effect of inclusion is positive by and large. When asked which of the countries in the BRICS group are the most important to cover, editors show a clear preference for China, with some highlighting Brazil and India as well. These responses are clearly aligned with the findings of the content analysis, which also indicated the dominance of China and India in terms of volume of coverage. The choice for China seems to be motivated mostly by the scale of its economy and concomitant influence in the BRICS group, although one respondent did remark that as far as ‘democratic relevance’ is concerned, India would be a better choice on which to focus coverage. Editors seem to have developed a more nuanced view of China over the course of the past few years. In response to the question whether their views of China’s involvement in Africa have changed in recent years, almost all respondents indicated that they have developed a better understanding and clearer position on China’s involvement in Africa. This does not necessarily mean that they have grown more sympathetic towards China, but that they have developed a more nuanced view. Two responses are illustrative: Yes, I now have more information about China and there are more on China to speak to in South Africa. My views have changed from suspicion to seeing China as a pragmatic actor working in different way with better results and growing its economy. Don’t think China is trying to colonize Africa. China needs Africa. (The) country (is) multi-facetted, (and it has) changed a lot in last 20 years and holds lessons. (China is) not a benign force coming into the country. (It) has self-interest at heart. SA has to do the same. and: The relationship is as ambivalent as it is important, and I think the real texture of what is happening is missed in both the ‘yellow peril’ discourse that runs through too much reporting on the subject, and the boosterism that is its counterpart. China’s own stance is evolving, and it seems to me to be a good deal more sophisticated than is often credited. The short answer is that my view is much the same, but there is more evidence and detail to support a nuanced view. On the whole, editors have therefore come to view the relationship between South Africa and China more circumspectly. Asked what aspects of the relationship between South Africa and its BRICS counterparts would be of most interest to their readers, there is a clear preference for trade, industry and business topics. However, editors also see their readers as being interested in the domestic political dimensions of the relationship – the African National Congress’s (ANC’s) ‘fascination with China’, for Downloaded from jas.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 12, 2016 120 Journal of Asian and African Studies 50(1) example – and in larger geopolitical issues, such as how the relationship will influence South Africa’s positions at the United Nations (UN). South Africa’s membership of BRICS is seen as providing the country with ‘bigger negotiating power’, ‘more international influence’ and ‘faster infrastructure development’. However, editors recognize that the BRICS group is a loose affiliation rather than an alliance. While the immediate benefits of South Africa’s inclusion in the grouping are economic in nature, the economic advantages are seen to translate into political capital, especially as the alignment provides a counter-hegemonic bloc to the established powers in the West: Clearly the benefits of economic integration ought to be growth, efficiency, and a stronger voice in multilateral negotiations that are still weighted toward the western powers. Editors largely agree that while BRICS is not a partnership of equals, there are benefits for South Africa from membership. One editor put it unequivocally: Certainly it’s not a partnership of equals, China is dominating. To a certain extent Brazil is a bit dominant as well, I’m not sure about Russia, I’m not sure if they belong to that group. Another made it clear that South Africa was at the bottom of the alignment: SA is the like the stepbrother, the adopted child, the johnny-come-lately. China is definitely head and shoulders above the other partners. Russia and India are closer to China but SA is definitely at the bottom with China dominating. For some editors, these views are influenced by their exposure to Chinese media outlets which – as described above – are increasingly becoming available in Africa. While some editors indicate that they consult Chinese media from time to time, they are careful to treat information gleaned in this way as the official party line from China, and therefore view it circumspectly: I refer to both Xinhua and CCTV from time to time, both for a sense of what the official Chinese line is on key issues, and for a sense of where Chinese interests lie. It is also interesting to get a sense of what is possible in China’s heavily controlled official media. This view was reiterated by another editor: We use them to try and give a context on how things are reported and represented there, but we are very careful to declare the nature of the paper, whether it’s partisan and alighted to the ruling party. To the extent that the development of these more nuanced views are reported by journalists to have developed in relation to their use of Chinese media, one may conclude that China’s ‘soft power’ initiatives by way of investment in media at the very least count among the various influences on journalistic attitudes and behaviours. Where exactly this influence fits within Reese’s (2001) hierarchy of influences, would require more extensive research into newsroom routines. Conclusion It is clear that within the BRICS alignment, the South Africa–China relationship is the one that preoccupies the media most. From the increased interpenetration of media capital – the extension of Chinese media platforms into African countries and the investment in Chinese media ventures by South African media capital – and the consistent high amount of coverage in the South African Downloaded from jas.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 12, 2016 121 Wasserman media, it is clear that the Chinese–South African engagement is increasingly going to be a mediated one. For the coverage to become more textured and to contribute to a better understanding of not only the economic and political impacts of the BRICS alignment and particularly the China– Africa relationship, but also the social and cultural implications, media would have to give more attention to the ‘downstairs’ relationships that evolve through the new geopolitics, and not only the ‘upstairs’ trade and exchange (cf. Park and Alden, 2013). Although coverage of the China–South Africa relationship has been cautiously optimistic over the past number of years, the media is likely to remain a central space where battles for representation, struggles for perceptions and jostling for influence over audiences will take place. Content analyses have shown that China dominates the coverage of BRICS partners. From the responses by journalists and editors, this dominance is likely to continue. While editors and journalists are not unequivocally positive about China’s dominance of the BRICS group or South Africa’s place in it, it is clear that they recognize the importance of providing coverage to this geopolitical alignment. However, coverage has tended to frame China’s involvement in Africa in economic and political terms. BRICS itself is an economic category, devised by an investment bank. For the media to contribute to a better understanding of the implications of China’s presence on the continent, it would also have to pay attention to the social and cultural aspects of the shifts in the global geopolitical order. Acknowledgements Thanks to Wadim Schreiner, Theresa Lötter and Lisl van Eeden from Media Tenor for assistance with content analysis data, and to Marietjie Oelofsen and Vanessa Malila for assistance in gathering interview data. Funding This work was supported by the Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange (grant number RG010-U-1). Notes 1. 2. This section draws on a more detailed background provided in Wasserman (2012). A slight difference between the content analysis in this latest study and Wasserman (2012) was that the previous study used individual statements within reports as units of analysis, while the current study used reports as units of analysis and coded the report as a whole for its attitude towards the topic. This explains the difference in total number of units between the two studies. References Alden C (2007) China in Africa. London: Zed Books. Bauer N (2013) South Africa, China get cozy ahead of BRICS summit. Mail & Guardian, 26 March. Available at: http://mg.co.za/article/2013-03-26-south-africa-china-get-cosy-ahead-of-brics-summit (accessed 26 March 2013). Bloom K and Poplak R (2012) Nosedive: Chinese shopkeeper cover story a new low for South African Journalism. Daily Maverick, 31 October. Available at: http://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/201210-30-nosedive-chinese-shopkeeper-cover-story-a-new-low-for-south-african-journalism (accessed 15 March 2013). Bremmer I (2012) United by a catchy acronym. The New York Times, 30 November. Available at: http://www. nytimes.com/2012/12/01/opinion/united-by-a-catchy-acronym.html?_r=4& (accessed 19 March 2013). Buthelezi L (2011) China’s stake in Africa grows. Business Report, 3 May, 1. Daly JCK (2009) Feeding the dragon: China’s quest for African minerals. In: Waldron A (ed.) China in Africa. Washington DC: The Jamestown Foundation, pp.78–85. Downloaded from jas.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 12, 2016 122 Journal of Asian and African Studies 50(1) Fabricius P (2013) SA plans to punt Africa at BRICS summit. Pretoria News, 25 February. Available at: http://www.iol.co.za/pretoria-news/opinion/sa-plans-to-punt-africa-at-brics-summit-1.1476366#. UVFXXVfXSys (accessed 26 March 2013). Harber A (2013) Update on China in African media. The Harbinger. Available at: http://www.theharbinger. co.za/wordpress/2013/07/08/update-on-china-in-african-media/ (accessed 5 September 2013). Keita M (2012) Africa’s free press problem. The New York Times, 15 April. Available at: http://www.nytimes. com/2012/04/16/opinion/africas-free-press-problem.html?_r2&ref opinion (accessed 19 March 2013). Kurlantzick J (2007) Charm Offensive: How China’s Soft Power is Transforming the World. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Le Pere G and Shelton G (2007) China, Africa, and South Africa. Midrand: Institute for Global Dialogue. Mills G and Thompson C (2009) Partners or predators? China in Africa. In: Waldron A (ed.) China in Africa. Washington, DC: The Jamestown Foundation, pp.55–60. Mnyandu E (2013) SA must weigh costs and benefits of its BRICS membership. Business Report, 11 March. Available at: http://www.iol.co.za/business/opinion/columnists/sa-must-weigh-costs-and-benefits-ofits-brics-membership-1.1483915#.UUhtw1fXSyu (accessed 19 March 2013). Nkoana-Mashabane M (2012) South Africa’s role in BRICS, and its benefits to job creation and the infrastructure drive in South Africa. Speech presented at The New Age Business Briefing, Johannesburg, 11 September 2012. Available at: http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/120911-nkoana-mashabane.html (accessed 18 March 2013). Noseweek (2012) Howzit China? Issue 157, 1 November. Available at: http://www.noseweek.co.za/article/2836/Howzit-China (accessed 19 March 2013). Nye J (2005) Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. New York: Public Affairs. Olsen K (2013) Xi trip highlights China’s Africa influence. Mail & Guardian, 21 March. Available at: http:// mg.co.za/article/2013–03–21-xi-trip-highlights-chinas-africa-influence (accessed 26 March 2013). Padayachee K, Jansen L and Khumalo S (2013) BRICS summit to cost R10m. Business Report, 6 March. Available at: http://www.iol.co.za/business/news/brics-summit-to-cost-r10m-1.1481619#. Upz1X8QW08E (accessed 18 March 2013). Park YJ and Alden C (2013) ‘Upstairs’ and ‘downstairs’ dimensions of China and the Chinese in South Africa. In: Pillay U, Hagg G and Nyamnjoh F (eds) State of the Nation 2012: Tackling Poverty and Inequality. Pretoria: HSRC Press, pp.643–662. Pieterse JN (2009) Representing the rise of the rest as threat: Media and global divides. Global Media and Communication 5(2): 221–237. Plaut M (2012) China’s ‘soft power’ offensive in Africa. Available at: http://martinplaut.wordpress. com/2012/11/23/chinas-soft-power-offensive-in-africa/ (accessed 20 March 2013). Reese SD (2001) Understanding the global journalist: A hierarchy-of-influences approach. Journalism Studies 2(2): 173–187. Roughneen S (2011) After BRIC comes MIST, the acronym Turkey would certainly welcome. The Guardian, 1 February. Available at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/global-development/poverty-matters/2011/feb/01/ emerging-economies-turkey-jim-oneill (accessed 18 March 2013). Sautman B and Hairong Y (2007) Fu Manchu in Africa: The distorted portrayal of China’s presence in the continent. South African Labor Bulletin 31(5): 34–38. Steyn L (2012) Naspers rides big Chinese wave. Mail & Guardian, 31 August. Available at: http://mg.co.za/ article/2012-08-31-naspers-rides-big-chinese-wave (accessed 21 March 2013). Taylor I (2013) The BRICS and the ‘new scramble for Africa’. In: seminar presented at the Afrika Studiecentrum, Leiden, Netherlands, 14 March. Thussu D (2010) ‘Chindia’ and global communication [Editorial]. Global Media and Communication 6(3): 243–245. Umejei E (2013). China is not the enemy-Sanef scribe. Open Source, 1 September. Available at: http://www. highwayafrica.com/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2013/09/Web-issue-1.pdf (accessed 5 September 2013). Umejei E and Hall B (2013) Wits prof worried about Chinese cash. Open Source, 2 September. Available at: http://www.highwayafrica.com/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2013/09/Web-Issue-2.pdf (accessed 5 September 2013). Downloaded from jas.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 12, 2016 123 Wasserman Waldron A (ed.) (2009) China in Africa. Washington, DC: The Jamestown Foundation. Wasserman H (2012). China in South Africa: The media’s response to a developing relationship. Chinese Journal of Communication 5(3): 336–354. Zakaria F (2011) The Post-American World (Release 2.0). New York: W.W. Norton & Co. Zeleza PT (2008) Dancing with the dragon: Africa’s courtship with China. The Global South 2(2): 171–187. Zheng L (2010) Neo-colonialism, ideology, or just business? China’s perception of Africa. Global Media and Communication 6(3): 271–276. Author biography Herman Wasserman is Professor and Deputy Head of the School of Journalism and Media Studies, Rhodes University, South Africa. He has published widely on media in post-apartheid South Africa, including the monograph Tabloid Journalism in South Africa: True Story (Indiana University Press, 2010) and edited volumes Popular Media, Democracy and Development in Africa (Routledge, 2010), Media Ethics Beyond Borders (with Stephen J Ward, Routledge, 2008) and Press Freedom in Africa: Comparative Perspectives (Routledge 2012). He edits the journal Ecquid Novi: African Journalism Studies. Downloaded from jas.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 12, 2016