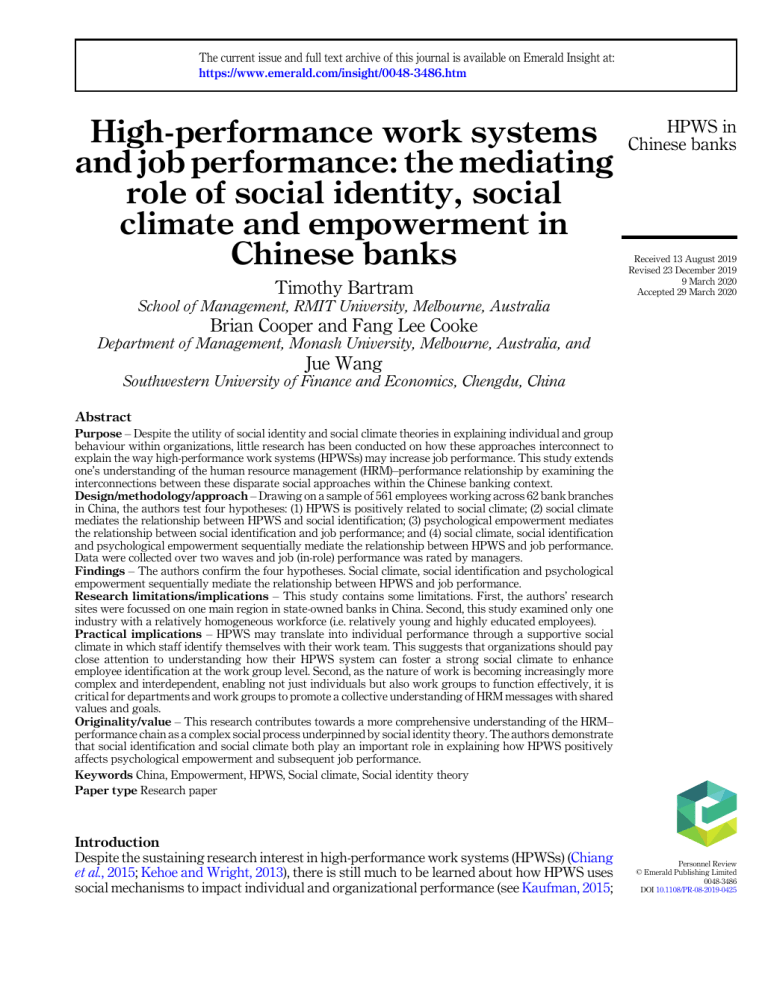

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/0048-3486.htm High-performance work systems and job performance: the mediating role of social identity, social climate and empowerment in Chinese banks Timothy Bartram HPWS in Chinese banks Received 13 August 2019 Revised 23 December 2019 9 March 2020 Accepted 29 March 2020 School of Management, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia Brian Cooper and Fang Lee Cooke Department of Management, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia, and Jue Wang Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, Chengdu, China Abstract Purpose – Despite the utility of social identity and social climate theories in explaining individual and group behaviour within organizations, little research has been conducted on how these approaches interconnect to explain the way high-performance work systems (HPWSs) may increase job performance. This study extends one’s understanding of the human resource management (HRM)–performance relationship by examining the interconnections between these disparate social approaches within the Chinese banking context. Design/methodology/approach – Drawing on a sample of 561 employees working across 62 bank branches in China, the authors test four hypotheses: (1) HPWS is positively related to social climate; (2) social climate mediates the relationship between HPWS and social identification; (3) psychological empowerment mediates the relationship between social identification and job performance; and (4) social climate, social identification and psychological empowerment sequentially mediate the relationship between HPWS and job performance. Data were collected over two waves and job (in-role) performance was rated by managers. Findings – The authors confirm the four hypotheses. Social climate, social identification and psychological empowerment sequentially mediate the relationship between HPWS and job performance. Research limitations/implications – This study contains some limitations. First, the authors’ research sites were focussed on one main region in state-owned banks in China. Second, this study examined only one industry with a relatively homogeneous workforce (i.e. relatively young and highly educated employees). Practical implications – HPWS may translate into individual performance through a supportive social climate in which staff identify themselves with their work team. This suggests that organizations should pay close attention to understanding how their HPWS system can foster a strong social climate to enhance employee identification at the work group level. Second, as the nature of work is becoming increasingly more complex and interdependent, enabling not just individuals but also work groups to function effectively, it is critical for departments and work groups to promote a collective understanding of HRM messages with shared values and goals. Originality/value – This research contributes towards a more comprehensive understanding of the HRM– performance chain as a complex social process underpinned by social identity theory. The authors demonstrate that social identification and social climate both play an important role in explaining how HPWS positively affects psychological empowerment and subsequent job performance. Keywords China, Empowerment, HPWS, Social climate, Social identity theory Paper type Research paper Introduction Despite the sustaining research interest in high-performance work systems (HPWSs) (Chiang et al., 2015; Kehoe and Wright, 2013), there is still much to be learned about how HPWS uses social mechanisms to impact individual and organizational performance (see Kaufman, 2015; Personnel Review © Emerald Publishing Limited 0048-3486 DOI 10.1108/PR-08-2019-0425 PR Paauwe et al., 2013). For most people, work is a social experience and employee perceptions of human resource management (HRM) practices may be influenced by their experiences with, as well as views of, their co-workers (De Sisto et al., 2019; Kehoe and Wright, 2013), broader organizational values (Coutu, 2002) and climates (Prieto and Santana, 2012). Management scholars and practitioners have a strong interest in the effective management of an increasingly service-dominated workforce to maximize organizational performance (Cooke et al., 2019; Fu et al., 2019). HPWS is important because it promotes people as a source of competitive advantage by developing human capital through a “bundle” of HRM practices that are designed to enhance employees’ knowledge, skills, commitment and performance (Miao et al., 2020; Xian et al., 2019; Wattoo et al., 2020). Researchers theorize that certain HRM practices (e.g. extensive training, information sharing, employee self-managed teams, quality work) are performance enhancing (Bartram et al., 2014; Takeuchi et al., 2009). Several scholars have proposed that HPWS impacts individual as well as organizational outcomes through social mechanisms including social climate (Collins and Smith, 2006; Evans and Davis, 2005; Wright and Haggerty, 2005) and more recently, social identification (e.g. Bartram et al., 2014; Cornelissen et al., 2007). Despite the growing research on HPWS as a social phenomenon, Takeuchi et al. (2009) argue that the social processes through which HRM affects employees’ attitudes and behaviours and performance remain inadequately understood. More specifically, there is little research examining how HPWS contributes to individual performance via its effect on social climate and on the social identification of workers (Badigannavar and Kelly, 2005; Bartram et al., 2007; Ellemers et al., 2004; Haslam, 2014). This is an important research gap because HPWS promotes the development of relationships, cooperation and synergy between work group members as a means of competitive advantage (Wright and Nishii, 2004). With the growing emphasis of organizations competing via complex service provision (to innovate and create) that require close collaboration, high levels of trust and communication, unpacking how HPWS can be used to build synergistic relationships among team or work group members to increase employee performance is important for both management scholars and practitioners. Our paper is underpinned by social identity theory which proposes that people wish to belong to groups (e.g. a bank branch) to enhance their self-esteem. Social identification is “a process whereby people develop a sense of themselves as a distinct group” (Badigannavar and Kelly, 2005, p. 527). Moreover, an important argument of our paper is that the development of a strong social climate is achieved through HPWS. Prieto and Santana (2012, p. 193) define social climate as the “mobilization of assets controlled through a ‘network of relationships’ among organizational members”. Such a social climate is underpinned by trust, cooperation and shared codes and language (Collins and Smith, 2006). This study proposes that creating a social climate of trust and cooperation (at the work-group level) will facilitate greater social identification among workers in which they enhance their effort on behalf of the work group through psychological empowerment and subsequent job (in-role) performance. According to Conger and Kanungo (1988), empowerment is a process of enhancing feelings of self-efficacy amongst organizational participants. Moreover, Spreitzer defined psychological empowerment as comprised of four cognitions: meaning; competence; autonomy; and impact. Social identification within the work group through the development of common individual and group reactions (e.g. common internalization of intended performance goals) is likely to drive higher levels of psychological empowerment and subsequent job performance (Bartram et al., 2014; Wright and Nishii, 2004). To examine these linkages, we test four hypotheses: (1) HPWS is positively related to social climate; (2) social climate mediates the relationship between HPWS and social identification; (3) psychological empowerment mediates the relationship between social identification and job performance; and (4) social climate, social identification and psychological empowerment sequentially mediate the relationship between HPWS and job performance. We selected the Chinese banking industry for the context of our study because it represents an important sector not just in China but also for the global economy in which work performance expectations are high due to intensive competition, and the work requires significant employee interaction and collaboration (Wang et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2012). The hypotheses are tested using 561 employee–manager matched observations from 62 branches from 16 banks in southwest China. Our study is situated at the work group level (i.e. at the bank branch level) because social identification is more likely to emerge in smaller groups where the greatest level of interaction occurs (Farmer et al., 2015; Haslam, 2014; Liu et al., 2014). Our paper contributes to the HRM literature in three ways. First, we extend extant research of HPWS and social identification through the inclusion of another social process – social climate. In doing so, this study seeks to extend and improve upon the methodological rigour of Bartram et al. (2014) by using a multi-level and multi-source (consisting of both employee measures and supervisor-rated performance) research design. Our main contribution to the HRM literature is unpacking the role of the three mediators (i.e. social climate, social identification and psychological empowerment) on the relationship between HPWS and job performance. Second, we examine the influence of HPWS on the relationship between group-level social phenomenon (social climate) and individual-level social phenomenon (social identification and psychological empowerment) to explain job performance. By using social identity theory, specifically the social categorization process to examine social climate and social identification across two different organizational levels, we gather new and important insights into how these two different social processes explain the impact of HPWS on job performance. Moreover, the paper contributes to HRM theory by shedding light on the social processes through which HRM may affect the attitudes and behaviours of workers (psychological empowerment) and their subsequent job performance. This is valuable because it gives both academics and management practitioners a more complete understanding of how HPWS uses multi-level social processes to facilitate greater social cohesion among work groups and increase their subsequent performance. Third, our study contributes to the HRM field by investigating the use of HPWS in the context of the Chinese banking industry, a vital financial sector with global implications (e.g. Zhao et al., 2012; Cooke et al., 2019) which remains under-researched. These research gaps are important to fill given the growing interdependent and complex nature of service work that requires significant social interaction and synergy between workers to provide high-quality services. Literature review and hypotheses development HPWS and social climate Research has shown that the operation of the HRM–performance chain is interconnected through complex relationships across individual, group and organizational levels (Collins and Smith, 2006; Ma et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018). Researchers theorize that certain HRM practices (e.g. extensive training, information sharing, employee self-managed teams and quality work) are performance enhancing (Wattoo et al., 2020). These practices affect employee attitudes and behaviours and consequently impact individual as well as organizational performance (Bartram et al., 2014; Xian et al., 2019). We propose that HPWS practices can foster a positive social climate within an organization. Social climate can be defined as “the collective set of norms, values, beliefs that express employees’ views of how they interact with one another while carrying out tasks for their firm” (Collins and Smith, 2006, p. 547). Existing literature demonstrates that HRM practices have a positive effect on HPWS in Chinese banks PR social climate through facilitating knowledge exchange and combination (Prieto and Santana, 2012) and the development of intellectual capital (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). HPWS may support the development of a strong positive social climate through creating interdependence and norms of reciprocity between workers and their work groups (Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005), which may generate high-quality relationships (Collins and Smith, 2006). Collins and Smith’s (2006) study of 136 high-tech American firms revealed that commitment-oriented HRM practices are positively associated with organizational climate. More specifically, we argue that HPWS practices including training and development, semi-autonomous work teams, quality work and information sharing will increase the social climate in a workplace. Extant research has shown that training and development have a positive effect on workplace relationships and employee well-being (Kooij et al., 2013). Moreover, semi-autonomous work teams, quality work design and information sharing may facilitate enhanced management and employee interaction, communication and cooperation and trust (Cheung et al., 2017; Gagne, 2009; Prieto and Santana, 2012). Taken together, we propose: H1. HPWS is positively related to social climate. HPWS, social climate and social identification Recent studies have turned their attention to the role of social identification in the HRM– performance chain within organizations (e.g. Andersen and Andersen, 2019; Bartram et al., 2014; Haslam, 2014). Social identity theory is a useful framework to understand how HPWS uses social processes to develop social identification and positive in-group behaviours (e.g. psychological empowerment) within work groups, which may lead to the increase of individual performance (Ashforth and Mael, 1989; Haslam, 2014; Kark et al., 2003). Studies have shown that HPWS practices (e.g. quality of work, participative leadership and semiautonomous teams) are associated with social cohesion, which is an important outcome of social identification (Campion et al., 1996; Forrester and Tashchian, 2006). Social identity theory proposes that people want to belong to social groups to increase their self-esteem. Moreover, “identification matters because it is a process by which people come to define themselves, communicate that definition to others, and use that definition to navigate their. . . work” (Ashforth et al., 2008, p. 334). This perception of belonging underpins an individual’s social identity (Tajfel and Turner, 1986). Social identification plays an important function in forming collective attitudes and associated behaviours (Lam et al., 2016). Social identification produces positive in-group attitudes and behaviours (Hogg and Terry, 2000; Lam et al., 2016). Social identity theory examines how social categorization produces prototype-based depersonalization of self (change in self-conception and the basis of perception of others) and others, thereby generating social identification (Abrams and Hogg, 2004; Hogg and Terry, 2000). Hogg and Terry’s (2000) seminal work on the social categorization process within social identity theory suggests that social categorization is the cognitive basis of group behaviour. The authors argue that social categorization enhances the perceived similarity of an individual with the relevant in-group prototype. As individuals become embodiments of the relevant prototype, a process of depersonalization occurs. Hogg and Terry (2000) argue that social categorization is a process through which an individual cognitively assimilates the self to the in-group prototype and therefore depersonalization occurs within their self-conception. This process produces “normative behavior, stereotyping, ethnocentrism, positive in-group attitudes and cohesion, cooperation and altruism, emotional contagion and empathy, collective behavior, shared norms, and mutual influence” (Hogg and Terry, 2000, p. 123). Depersonalization is defined as “a change in self-conceptualization and the basis of perception of others” (Hogg and Terry, 2000, p. 123). Prototypes are defined as “fuzzy sets that capture the context-dependent features of group membership, often in the form of representations of exemplary members or ideal types” and “embody all attributes that characterize groups and distinguish them from other groups, including beliefs, attitudes, feelings, and behaviors” (Hogg and Terry, 2000, p. 123). Cohesion and solidarity are underpinned by perceived group prototypicality. When a group is salient, in-group members are preferred if they embody the in-group prototype. There is limited research that directly examines the effect of social climate in an organization on workers’ social identification, although recent research has found that organizational support shapes employees’ organizational identification (Lam et al., 2016). Given that social climate is premised upon social relationships of individuals within a work group (Prieto and Santana, 2012) and is underpinned by trust, cooperation and shared codes and language that exist among individuals within a team (Collins and Smith, 2006; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998), we argue that social climate may be important in the formation of social identification of individuals in the work unit. Our reasoning is as follows. Ashforth and Mael (1989) argue that internalization through traditional factors that underpin group formation (e.g. shared mission and goals, frequent interpersonal interaction and strong organizational climate) may create a salient, internally consistent and desirable situation, which may subsequently promote individual identification with work groups in organizations. Using the social categorization process (Hogg and Terry, 2000), we argue that HPWS may strengthen (through extensive training, information sharing, employee selfmanaged teams, quality work) social climate (e.g. trust, cooperation and common forms of language) which may facilitate social identification through the cognitive assimilation of individuals through depersonalization to the in-group prototype. HPWS through social climate may facilitate this process through creating a strong prototype by highlighting the attractive features of group membership (e.g. extensive training, information sharing, quality work, trust and cooperation among work unit members) and the success of exemplary prototypical members. As individuals become attracted to such a group, they become embodiments of the relevant prototype (they take on the norms, values, attitudes and behaviours of the group) and a process of depersonalization occurs. Using HPWS, managers may promote desirable attributes of the organization and work unit. HPWS practices that strengthen the social climate within work units (e.g. bank branches) may produce favourable in-group attitudes, cohesion, shared norms, altruism and empathy towards the group and its members – that is, increasing the prototypicality of the group, depersonalization and promotion of social identification. As individuals are motivated by either/or in combination of self-enhancement and uncertainty reduction, belonging to a group with high prototypicality (as facilitated by HPWS and strong social climate) is made more attractive as the group provides moral support and validation of an individual’s self-concept (Alderfer, 1987). Such a positive group context may promote social identification as group membership may raise individual self-esteem as people develop stronger and more fulfilling relationships with group members and internalize the goals of the workgroup and organization (Shamir, 1990). Given that in Hypothesis 1, we have established that HPWS may predict social climate, we propose the following hypothesis: H2. Social climate mediates the relationship between HPWS and social identification. HPWS, social identification and psychological empowerment In this section, we examine the theoretical and empirical reasoning for an alternative mechanism whereby social identification mediates the relationship between HPWS and psychological empowerment. Psychological empowerment enables workers to enhance their self-efficacy, develop meaning for their work tasks and enhance their competency HPWS in Chinese banks PR (Conger and Kanungo, 1988; Laschinger et al., 2004). Bartram et al. (2014) established that social identification mediated the relationship between HPWS and psychological empowerment using a sample of 201 Australian nurses. We examine further how each HPWS practice can promote the social identification of employees. Extensive training at the team level, for instance, can increase communication flows and subsequent coordination of activities among team members. This may promote the development of shared understanding of tasks among team members (Postmes, 2003). Selfmanaged teams and decentralized decision-making can promote familiarity among team members and support greater social cohesion (Pfeffer, 1998; Hogg and Terry, 2000). Factors such as group prestige and distinctiveness are also seen to influence group identification (Gundlach et al., 2006). High-quality work sends a signal to workers that they are valuable and are valued by the work group/organization (Pfeffer, 1998) which strengthens the prototypicality of the work group (e.g. bank branch). Through depersonalization, this may create a stronger feeling of belonging and loyalty of workers to their work group. Information sharing about business performance at the organizational and work group level is critical to HPWS in that it signals to employees that they are trusted and an important part of business success (Pfeffer, 1998). Social psychology literature suggests that social identification may be positively associated with psychological empowerment given that identification with the group has important “perceptual, motivational, and behavioral consequences” (Kark et al., 2003, p. 248). Kark et al.’s (2003) study revealed that social identification mediated the relationship between transformation leadership and followers’ psychological empowerment. We now examine the theoretical rationale for how social identification may affect each component of psychological empowerment. First, strong social identification may enhance the intrinsic value and meaning of an individual’s efforts with regard to the achievement of collective goals (Shamir et al., 1993). As people seek meaning in their lives, the process of identifying with groups helps reduce uncertainty in external and internal organizational environments and create deeper meanings and feelings of connection with the in-group (Hogg and Terry, 2000). Hogg and Terry (2000) argue that the self-categorization process promotes an individual’s cognitive assimilation with the in-group prototype encouraging depersonalization which produces positive in-group attitudes and cohesion, altruism and emotional contagion. In this situation, individuals are more likely to exert extra effort on behalf of their work group, especially in work groups that use HPWS. Second, Wood and Bandura (1989) suggest that an individual’s self-efficacy will be affected by mastery experiences, modelling or learning from others and social persuasion such as realistic encouragement. We argue that those individuals who identify strongly with their work unit and prototypical group members will have greater access to learn from others, enjoy their encouragement and therefore develop greater success from learning episodes. This can be explained by group members’ positive in-group attitudes and empathy especially towards members who display prototypical attitudes and behaviours (Hogg and Terry, 2000). Moreover, social identification within a group may provide individual members with psychological safety and feelings of self-efficacy which is central to the self-categorization process (Ashforth et al., 2008; Hogg, 1993). Third, in relation to impact, we suggest that given the positive outcomes of social identification (e.g. in-group cohesion, cooperation and altruism), group members will celebrate the impact of individuals’ efforts associated with the achievement of collective goals. This further reinforces the high prototypicality of the group, its distinctiveness and the importance of self-enhancement of individual members (Hogg and Terry, 2000). Fourth, the influence of social identification on autonomy is complex and not fully understood. We suggest that at the heart of HPWS is the promotion of autonomy, self-reliance and skill enhancement of the individual so that they can contribute their best to the work group (Bartram et al., 2014). Organizations that use HPWS should create prototypical values that enable and strengthen an individual’s sense of autonomy to attract them to the group and increase their self-efficacy. Alternatively, social identification may increase the propensity for conformity to group norms and may even stifle autonomy. Extant research has demonstrated that psychologically empowered employees feel committed to their jobs and are more productive overall (Bos-Nehles et al., 2013; Laschinger et al., 2004; Mishra and Spreitzer, 1998). We therefore propose: H3. Psychological empowerment mediates the relationship between HPWS and social identification. HPWS, social climate, social identification, psychological empowerment and job performance Given the aforementioned three hypotheses, we propose a serial mediation hypothesis such that social climate, social identification and psychological empowerment will sequentially mediate the relationship between HPWS and job performance. Social identity theory, through the social categorization process, can inform the proposed sequential mediation hypothesis. As noted earlier, we argue that HPWS may help build a social climate at the branch level which may enhance, through establishing trust, cooperation and common forms of language, a propensity for employees to socially identify with their work group through a process of self-categorization in which depersonalization occurs given high prototypicality and desirability of group membership (Hogg and Terry, 2000). As depersonalization occurs, individuals will model themselves on “exemplary members or ideal types” and attempt to “embody. . .. the beliefs, attitudes, feelings, and behaviors” of the in-group (Hogg and Terry, 2000, p. 123). This process is facilitated by HPWS and social climate that make the group prototype simple, clear and consensual for individuals to embody (Hogg and Terry, 2000). Moreover, HPWS and social climate may promote perceived similarity of an individual to the in-group (e.g. bank branch) through creating a desirable prototype in which he/she depersonalizes the self as a means of increasing their self-esteem (e.g. I can get promoted) and/or uncertainty reduction (e.g. I know how to behave to be accepted and supported). Hogg and Terry argue that group cohesion is a reflection of depersonalized, prototype-based inter-individual attitudes. Social categorization, promoted by HPWS and a strong social climate, may encourage an individual to embody the prototypical values, attitudes and behaviours of the in-group which may create a situation of favourable treatment (e.g. support, empathy and practical help for prototypical members). This process may promote positive social cohesion and positive in-group member attitudes (e.g. psychological empowerment) and ultimately high levels of in-role performance through a willingness to exert effort on behalf of the group (Hogg, 1993). The “sense of oneness” that develops between an individual and group strengthens the team members’ willingness to contribute personal resources to the organization (Cregan et al., 2009). This process may facilitate an increase in “ability” through training, development and learning as team members share knowledge, skills and socialize (Wood and Bandura, 1989). Moreover, a workgroup that promotes trust and cooperation will have individual members that have a higher social identification and subsequently exhibit strong group loyalty because they have a positive impression of their group membership (Van Vugt and Hart, 2004). These individuals will be highly motivated as they transcend their self-interest for group purposes. Work teams with strong group identification create opportunities for members to learn, grow and demonstrate their loyalty through performance (Shamir et al., 1993; Sterling and Boxall, 2013). A substantial amount of research over the last two decades has demonstrated that psychological empowerment predicts employee job performance (Bartram et al., 2014; HPWS in Chinese banks PR Fong and Snape, 2015; Spreitzer, 1996). Seibert et al. (2011, p. 985) suggest that “theorists have argued that psychologically empowered employees anticipate problems . . .. exert influence over goals and operational procedures so that they can produce high-quality work outcomes and demonstrate persistence and resourcefulness in the face of obstacles to work goal accomplishment”. Taken together (and as summarized in Figure 1) with the reasoning of the aforementioned hypotheses, we propose: H4. Social climate, social identification and psychological empowerment sequentially mediate the relationship between HPWS and job performance. Method Sample and procedure We gathered questionnaire data from employees and their immediate managers in 62 branches from 16 banks in southwest China during 2014 and 2015. A full description of the sample can be found in anonymous (2019). In the first phase of data collection, the 62 branch managers were given hard-copy questionnaires and asked to distribute them to up to 15 subordinate employees they were responsible for randomly. In the second phase, six months later, questionnaires were distributed to the same managers to obtain ratings of each employee’s job performance. All participants were assured of confidentiality and the two sets of questionnaires were coded so they could be matched. We received 561 matched employee–manager responses (an average of approximately nine employees per branch), yielding a response rate of 95%. We obtained this relatively high response rate largely due to the fact that one of the authors went to each of the bank branches with a research assistant to carefully explain the purpose of the study and its benefits to each organization, and this was further complemented by reminders being sent to the managers responsible for collecting the questionnaires. In addition, the university for which this author works specializes in the finance and economic education and has a strong institutional connection with the finance sector. Some of the employees and managers were educated by this university and therefore have the affinity with the university and research that would be beneficial to their people management and bank performance. In terms of the sample profile, the overwhelming majority (85%) of the employees were aged under 30 years and just over half (53%) were female. The average hours worked per normal week was 45 (SD 5 7), and they had worked on average five years (SD 5 6) with their bank. The vast majority of respondents (81%) had a bachelor’s degree or diploma. Measures For all focal measures, participants rated the items using a five-point scale (1 5 “strongly disagree” to 5 5 “strongly agree”). We measured HPWS using five dimensions from the scale developed by Zacharatos et al. (2005): training and development/learning (five items); job quality (five items); information HPWS Social climate Branch Figure 1. Proposed conceptual model Employee Social idenficaon Psychological empowerment Job performance sharing (six items); use of teams (five items); and relationship with immediate manager (five items). We created an additive index of HPWS by summing the 26 items (α 5 0.88). Employees rated the social climate of the bank branch using Prieto and Santana’s (2012) ten-item scale. A sample item is “Employees in this organisation have relationships based on trust and reciprocation”. We averaged the ten items to form a composite measure, with higher scores indicating a more positive social climate (α 5 0.94). Social identification was measured using three items from the scale developed by Hinkle et al. (1989). A sample item is “I am glad I belong to my branch”. We averaged the three items to form a composite measure, with higher scores indicating greater work-unit identification (α 5 0.73). We assessed psychological empowerment using the 12-item scale developed by Spreitzer. This previously well-validated measure consists of four three-item sub-scales tapping the psychological empowerment dimensions of meaning, competence, self-determination and impact. In line with Spreitzer, we averaged the four sub-scales to form an overall psychological empowerment score (α 5 0.89). The branch manager rated the job performance of each employee in their unit using Williams and Anderson’s seven-item scale. A sample item is “this person meets the formal performance requirements of their job”. We averaged the seven items to form a composite measure of job (in-role) performance (α 5 0.86). Control variables In line with prior work (Bartram et al., 2014, anonymous, 2019), we included age of the employee (measured on a six-point scale from 1 ≤ 25 years to 6 5 65 years and over), their gender (1 5 male, 0 5 female), education level (coded 1 5 secondary school or less to 3 5 post graduate or higher) and hours worked per week as control variables. We did not include job tenure as a control variable as it was highly correlated with age (r 5 0.84) and would lead to concerns over multicollinearity. At the branch level, we included the size of the branch as a possible confounder of the relationship between HPWS and social climate (e.g. smaller branches may have more favourable social climates). Method of analysis Multi-level modelling was used to analyse the data as the study had variables at both the individual (employee) and work group (branch) levels. Using robust maximum likelihood estimation in Mplus 7.4, we tested the hypothesized indirect effects using the approach recommended by Pituch and Stapleton for group-level and participant-level mediators. To test the mediation hypotheses, we utilized the Monte Carlo method for testing indirect effects calculated using the asymptotic covariance matrix of estimates and the recommended 20,000 random simulated draws to construct the sampling distribution for each indirect effect (cf. Preacher and Selig, 2012). A Monte Carlo simulation is a useful and statistically powerful procedure that can be used where non-parametric bootstrapping is not easily conducted, such as with multi-level data. It can also be easily applied where there were three or more mediators in sequence, such as that for testing our serial mediation hypothesis (Hypothesis 4) in the present study (Tofighi and MacKinnon, 2015). Results Construct validity To test convergent and discriminant validity, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted for the five study constructs (HPWS, social climate, social identification, psychological empowerment and job performance). We used scale items as indicators, except HPWS in Chinese banks PR for HPWS and psychological empowerment where we used the sub-scales as indicators. This five-factor model (using robust maximum likelihood estimation with a correction for nonindependence of observations) yielded a relatively good fit χ 2 (df 5 615) 5 1,502; RMSEA 5 0.05, TLI 5 0.90; CFI 5 0.90. A four-factor model combining social identification and psychological empowerment yielded a poorer fit χ 2 (df 5 618) 5 1,714; RMSEA 5 0.06, TLI 5 0.87; CFI 5 0.87, as did a four-factor model combining social climate and HPWS, χ 2 (df 5 618) 5 2,806; RMSEA 5 0.07, TLI 5 0.82; CFI 5 0.83. A one-factor measurement model (where all indicators loaded on to a common factor) resulted in a very poor fit, χ 2 (df 5 619) 5 3,175, RMSEA 5 0.09, TLI 5 0.77, CFI 5 0.78. These results provide evidence for construct validity of the measures used in our study. Aggregation tests We conceptualized HPWS and social climate as work group (branch) level constructs. The mean within-group agreement (rwg) for the HPWS measure was 0.98 and 0.97 for the social climate measure, indicating excellent within-group consensus. The ICC1 (intraclass correlation) values for HPWS and social climate were acceptable (0.22 and 0.20, respectively) and the corresponding ICC2 values (which measure the reliability of the aggregated group means) were also acceptable (0.72 and 0.71). These results demonstrate it is appropriate to aggregate and examine HPWS and social climate as work group-level constructs. Multi-level modelling Table 1 reports the means, standard deviations and correlations of our study variables. Table 2 presents the full results of our multi-level regression analyses, whereas Figure 1 presents a summary of the results of our hypothesized mediation model. Hypothesis 1 predicted that HPWS is positively related to social climate. To minimize the risk of common method variance in testing this group-level hypothesis, we followed Ostroff et al.’s split sample approach and randomly selected 50% of employees within each branch to construct the HPWS scores and the remaining 50% to construct the social climate scores. In support of Hypothesis 1, we found a positive relationship between HPWS and social climate (β 5 32, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 2 predicted that social climate mediates the relationship between HPWS and social identification. A Monte Carlo confidence interval for the indirect effect of HPWS on social identification via social climate was 0.09 (95% CI: 0.02–0.16). Given that the 95% confidence interval excludes zero, Hypothesis 2 was supported. Hypothesis 3 predicted that psychological empowerment mediates the relationship between social identification and job performance. A Monte Carlo confidence interval for the indirect effect of social identification on job performance via psychological empowerment was 0.05 (95% CI: 0.01–0.10) and excludes zero. Hence, Hypothesis 3 was supported. Hypothesis 4 predicted that social climate, social identification and psychological empowerment sequentially mediate the relationship between HPWS and job performance. As shown in Figure 2, this is a complex four-path serial mediation model where three mediators (social climate, social identification and psychological empowerment intervene in a series between HPWS and job performance (Tofighi and MacKinnon, 2015). A Monte Carlo confidence interval for the indirect effect of HPWS on job performance via the three mediators in sequence was 0.01 (95% CI 5 0.005–0.2), thereby supporting Hypothesis 4. As shown in Figure 2, in addition to its indirect effect via social identification, social climate had a direct positive effect on psychological empowerment (β 5 11, p < 0.05). Finally, Table 2 shows that HPWS, holding constant all variables in the model, had a positive relationship with job performance (β 5 14, p < 0.05), suggesting there may be other 87.84 3.66 2.69 M 7.10 0.37 0.97 SD 0.38* 0.04 1 0.10 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Employee 4 Job performance 4.00 0.54 0.18** 0.02 0.06 5 Social identification 3.65 0.61 0.38** 0.36** 0.06 0.17** 6 Empowerment 3.47 0.57 0.32** 0.35** 0.09* 0.14** 0.55** 7 Gender 0.47 0.50 0.05 0.01 0.08 0.05 0.02 0.06 8 Age 2.00 0.67 0.10* 0.16** 0.01 0.09* 0.06 0.03 0.11** 9 Education 2.15 0.40 0.02 0.01 0.08 0.02 0.02 0.05 0.03 0.06 10 Hours worked 45.43 7.33 0.05 18** 0.02 0.02 0.16** 0.20** 0.13** 0.06 0.15** Note(s): Gender coded 1 5 male, 0 5 female. Age coded 1 ≤ 25 years to 6 5 65 years and over. Level of education coded 1 5 high school to 3 5 masters or higher. Branch size coded 1 ≤ 25 employees to 5 ≥ 50 employees. Branch-level variables (branch size, HPWS and social climate) are assigned down to correlate with employee-level variables. N 5 561 employees nested within 62 branches and 16 banks *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01 *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed) **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed) Branch 1 HPWS 2 Social climate 3 Branch size Variable HPWS in Chinese banks Table 1. Means, standard deviations and correlations among the study variables PR Model 1 Social climate (level-2) Model 2 Social identification – – – – – 0.01 (0.04) 0.06 (0.04) 0.03(0.04) 0.08 (0.04)* – – Level-1 Gender Age Education Hours worked Social ID Empowerment Table 2. Results of multi-level regression analyses Model 4 Job performance 0.06 (0.03) 0.09 (0.04)* 0.05 (0.03) 0.08 (0.06) 0.47 (0.06)** 0.03 (0.04) 0.01 (0.05) 0.05 (0.04) 0.08 (0.04) 0.12 (0.05)* 0.11 (0.04)* Level-2 Branch size 0.04 (0.14) 0.01 (0.03) 0.01 (0.02) 0.01 (0.03) HPWS 0.32(0.11)** 0.26 (0.03)** 0.14 (0.05)** 0.14 (0.07)* Social climate – 0.27 (0.06)** 0.11 (0.05)* 0.08 (0.09) 0.10 0.21 0.37 0.06 R2 Note(s): Standardized regression coefficients reported with robust standard errors in parentheses. R2 based on total variance explained. N 5 561 employees within 62 branches and 16 banks *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01 HPWS Branch Employee Figure 2. Results of hypothesized mediation model Model 3 Empowerment 0.32** Social climate 0.26** 0.47** Social idenficaon 0.11* Psychological empowerment Job performance Note(s): Standardized regression coefficients reported. N = 561 employees nested within 62 branches and 16 banks. Control variables were included in the modelestimationbut not shown for ease of presentation. *p < .05** p < .01 mechanisms through which HPWS impacts job performance other than the social processes studied here. With regard to the robustness of our findings, statistical inferences for our four hypotheses were not impacted by the inclusion of random or fixed effects at the bank level in the estimated models, suggesting that the branch level is the appropriate level of analysis to test the hypotheses. Discussion This study contributes to HPWS research by examining how HPWS utilizes social processes to increase job performance. It demonstrates that social climate and social identification both play an important role in explaining how HPWS positively affects psychological empowerment and subsequent job performance. We found full support for all our hypotheses: HPWS was positively related to social climate; social climate mediated the relationship between HPWS and social identification; and psychological empowerment mediated the relationship between social identification and job performance. Moreover, our exploratory hypothesis, which stated that social climate, social identification and psychological empowerment sequentially mediated the relationship between HPWS and job performance, was also supported. Our findings suggest that at the heart of the HRM– performance chain is the critical role of social identification through social categorization in professional work groups such as Chinese bank branches. We examine further the theoretical implications of our findings for HRM scholars and present practical implications for HR managers, discuss limitations and avenues for future research. Theoretical contributions We contribute to the advancement of both HRM and social identity theory. First, we contribute to social identity theory through its application to HRM by shedding greater light on how social identification processes, through serial mediation, inform our understanding of the HRM–performance chain. Our study fills a research gap by examining how HPWS may contribute to a strong social climate which may enable social identification, impact psychological empowerment and ultimately the job performance of employees. We demonstrate the efficacy of social identity theory in explaining the serial mediation process, in particular, how social climate at the work group level may enable social identification to take place. We argue that social categorization may facilitate the serial mediation process as HPWS may create a strong prototype by highlighting the attractive features of group membership (e.g. extensive training, information sharing, quality work, trust and cooperation among work-unit members). Second, using social identity theory, we have been able to shed new light on how HPWS may contribute to enhancing employee performance through multi-level social processes. We contribute to further understanding of how group-level (e.g. bank branch) HPWS and social climate may affect employee attitudes towards their branch and subsequent in-role performance. Social climate through HPWS may enhance both the attractiveness of group membership and prototypicality of the group that encourages further depersonalization of individual members, increasing their social identification with the group and their sense of belonging which has positive performance implications. Practical implications Our study has important management implications. First, HPWS may translate into individual performance though a supportive social climate in which staff identify themselves with their work team. This suggests that organizations should pay close attention to understanding how their HPWS system can foster a strong social climate to enhance employee identification. In particular, the effective implementation of HPWS by line managers will play a major role in supporting a strong social climate and social identification in work groups through social categorization processes (Boxall and Purcell, 2011). This may require further management and leadership development of line managers to ensure they have a strong understanding of HPWS functions, their implementation and evaluation, as well as their role in supporting a strong social climate and the processes through which people belong to groups. Effective management development is particularly important in China because of the shortage of well-qualified managers, and firms tend to recruit rather than train them in-house (e.g. Cooke et al., 2014). Second, as the nature of work is becoming increasingly more complex and interdependent, enabling not just individuals but also work groups to function effectively, it is critical for departments and work groups to promote a collective understanding of HRM messages with shared values and goals (Bowen and Ostroff, 2004). Our findings demonstrate that HPWS may promote a strong social climate and subsequent social identification with performance implications largely through social categorization in which individuals’ depersonalization to group prototypes is critical. Managers need to invest in developing strong work group prototypes that facilitate greater cohesion, emotional contagion and empathy among work HPWS in Chinese banks PR group members (Hogg and Terry, 2000). This may be achieved through the implementation of HPWS that invests in training, development and learning, provides high-quality jobs and promotes information sharing and productive relationships with the immediate managers (Boxall et al., 2011; Ulrich, 2016). Limitations and future research direction This study contains some limitations. First, our research sites were focussed on one main region in a large country, although state-owned banks in China operate in a relatively similar environment and regulatory constraints. Second, our study examined only one industry with a relatively homogeneous workforce (i.e. relatively young and highly educated employees who are mostly on fixed-term employment contract and performance-related pay). This constrains the generalizability of our research findings to other national settings, industrial sectors or ownership forms. It is unclear if the same outcomes would be achieved at workplaces where the workforce profile is more diverse and performance pressure may be less. Future research should test these hypotheses in different industrial sectors and locations and in other societal contexts, especially in developing countries where banks remain mostly state-owned/controlled and are going through reform processes to improve efficiency and become more market-oriented. Third, although previous work suggests that HR systems are an antecedent of employee’s subjective attitudes and behaviours (Kehoe and Wright, 2013), we acknowledge it is possible that social identification and psychological empowerment are impacted by reverse causation. It is worth noting that a major strength of our study was the six-month time lag between measurement of job performance (supervisor-rated) and the antecedent (employee-rated) variables. This design significantly strengthens our confidence that the study independent variables are an antecedent of job performance. Conclusion This study examines the effect of HPWS through social processes on job performance in a Chinese banking setting. We found that social mechanisms, underpinned by social identity theory, are useful to explain how HPWS may affect job performance. Our findings suggest that HPWS influences job performance through complex mechanisms related to social climate, social identification and psychological empowerment. Our findings extend the knowledge of the HRM–performance chain as a social process. References Abrams, D. and Hogg, M. (2004), “Metatheory: lessons from social identity research”, Personality and Social Psychology Review, Vol. 8, pp. 98-106. Alderfer, G.P. (1987), “An intergroup perspective on group dynamics”, in Lorsch, J.W. (Ed.), Handbook of Organizational Behavior, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, pp. 199-222. Andersen, J. and Andersen, A. (2019), “Are high-performance work systems (HPWS) appreciated by everyone? The role of management position and gender on the relationship between HPWS and affective commitment”, Employee Relations: The International Journal. doi: 10.1108/ER-03-20180080, available at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/full/html. Ashforth, B.E. and Mael, F. (1989), “Social identity theory and the organization”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14, pp. 20-39. Ashforth, B.E., Harrison, S.H. and Corley, K.G. (2008), “Identification in organizations: an examination of four fundamental questions”, Journal of Management, Vol. 34, pp. 325-374. Badigannavar, V. and Kelly, J. (2005), “Why are some union organising campaigns more successful than others?”, British Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 43, pp. 515-535. Bartram, T., Stanton, P., Leggat, S.G., Casimir, G. and Fraser, B. (2007), “Lost in translation: making the link between HRM and performance in healthcare”, Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 17, pp. 21-41. Bartram, T., Karimi, L., Leggat, S.G. and Stanton, P. (2014), “Social identification: linking high performance work systems, psychological empowerment and patient care”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 25, pp. 2401-2419. Bos-Nehles, A., van Riemsdijk, M. and Looise, J.K. (2013), “Employee perceptions of line management performance: applying the AMO theory to explain the effectiveness of line managers’ HRM implementation”, Human Resource Management, Vol. 52, pp. 861-877. Bowen, D. and Ostroff, C. (2004), “Understanding HRM-firm performance linkages: the role of the ‘strength’ of the HRM system”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 29, pp. 203-221. Boxall, P. and Purcell, J. (2011), Strategy and Human Resource Management, 3rd ed., Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke. Boxall, P., Ang, S.H. and Bartram, T. (2011), “Analysing the ‘black box’ of HRM: uncovering HR goals, mediators, and outcomes in a standardized service environment”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 48, pp. 1504-1532. Campion, M.A., Papper, M. and Medsker, G.J. (1996), “Relations between work team characteristics and effectiveness: a replication and extension”, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 49, pp. 429-452. Cheung, M.F.Y., Wong, C. and Yuan, G.Y. (2017), “Why mutual trust leads to highest performance: the mediating role of psychological contract fulfilment”, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 55, pp. 430-453. Chiang, Y.H., Hsu, C.C. and Shih, H.A. (2015), “Experienced high performance work system, extroversion personality, and creativity performance”, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 32, pp. 531-549. Collins, C.J. and Smith, K. (2006), “Knowledge exchange and combination: the role of human resource practices in the performance of high-tech firms”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 49, pp. 544-560. Conger, J.A. and Kanungo, R.N. (1988), “The empowerment process: integrating theory and practice”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 13, pp. 471-482. Cooke, F.L., Saini, D. and Wang, J. (2014), “Talent management in China and India: a comparison of management perceptions and human resource practices”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 49, pp. 225-235. Cooke, F.L., Cooper, B., Bartram, T., Wang, J. and Mei, H. (2019), “Mapping the relationships between high-performance work systems, employee resilience and engagement: a study of the banking industry in China”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 30, pp. 1239-1260. Cornelissen, J.P., Haslam, S.A. and Balmer, J.M. (2007), “Social identity, organizational identity and corporate identity: towards an integrated understanding of processes, patternings and products”, British Journal of Management, Vol. 18, pp. 1-16. Coutu, D.L. (2002), “How resilience works”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 80, pp. 46-56. Cregan, C., Bartram, T. and Stanton, P. (2009), “Union organizing as a mobilizing strategy: the impact of social identity and transformational leadership on the collectivism of union members”, British Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 47, pp. 701-722. Cropanzano, R. and Mitchell, M.S. (2005), “Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review”, Journal of Management, Vol. 31, pp. 874-900. De Sisto, M., Cavanagh, J., McMurray, A. and Bartram, T. (2019), “Emergency management and HRM in local governments: HR professionals as network managers”, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 57, pp. 227-246. HPWS in Chinese banks PR Ellemers, N.D., Gilder, D.E. and Haslam, S.A. (2004), “Motivating individuals and groups at work: a social identity perspective on leadership and group performance”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 29, pp. 459-478. Evans, W.R. and Davis, W.D. (2005), “High-performance work systems and organizational performance: the mediating role of internal social structure”, Journal of Management, Vol. 31, pp. 758-775. Farmer, S.M., Van Dyne, L. and Kamdar, D. (2015), “The contextualized self: how team–member exchange leads to coworker identification and helping OCB”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 100, pp. 583-595. Fong, K.H. and Snape, E. (2015), “Empowering leadership, psychological empowerment and employee Outcomes: testing a multi-level mediating model”, British Journal of Management, Vol. 26, pp. 126-138. Forrester, W.R. and Tashchian, A. (2006), “Modeling the relationship between cohesion and performance in student workgroups”, International Journal of Management, Vol. 23, pp. 458-464. Fu, N., Bosak, J., Flood, P.C. and Ma, Q. (2019), “Chinese and Irish professional service firms compared: linking HPWS, organizational coordination, and firm performance”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 95, pp. 266-276. Gagne, M. (2009), “A model of knowledge-sharing motivation”, Human Resource Management, Vol. 48, pp. 571-589. Gundlach, M., Zivnuska, S. and Stoner, J. (2006), “Understanding the relationship between individualism-collectivism and team performance through integration of social identity theory and the social relations model”, Human Relations, Vol. 59, pp. 1603-1632. Haslam, S.A. (2014), “Making good theory practical: five lessons for an Applied Social Identity Approach to challenges of organizational, health, and clinical psychology”, British Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 53, pp. 1-20. Hinkle, S., Taylor, L.A., Fox-Cardamone, L.D. and Crooke, K.E. (1989), “Intra-group identification and intergroup differentiation: a multi-component approach”, British Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 28, pp. 305-317. Hogg, M.A. (1993), “Group cohesiveness: a critical review and some new directions”, European Review of Social Psychology, Vol. 4, pp. 85-111. Hogg, M.A. and Terry, D.I. (2000), “Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 25, pp. 121-140. Kark, R., Shamir, B. and Chen, G. (2003), “The two faces of transformational leadership: empowerment and dependency”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 88, pp. 246-255. Kaufman, B. (2015), “Evolution of strategic HRM as seen through two founding books: a 30th anniversary perspective on development of the field”, Human Resource Management, Vol. 54, pp. 389-407. Kehoe, R.R. and Wright, P.M. (2013), “The impact of high-performance human resource practices on employees’ attitudes and behaviors”, Journal of Management, Vol. 39, pp. 366-391. Kooij, D.T., Guest, D.E., Clinton, M., Knight, T., Jansen, P.G.W. and Dikkers, J.S.E. (2013), “How the impact of HR practices on employee well-being and performance changes with age”, Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 23, pp. 18-35. Lam, L.W., Liu, Y. and Loi, R. (2016), “Looking intra-organizationally for identity cues: whether perceived organizational support shapes employees’ organizational identification”, Human Relations, Vol. 69, pp. 345-367. Laschinger, H.K.S., Finegan, J., Shamian, J. and Wilk, P. (2004), “A longitudinal analysis of the impact of workplace empowerment on work satisfaction”, Journal of Organizational Behaviour, Vol. 25, pp. 527-545. Liu, Y., Lam, L.W. and Loi, R. (2014), “Examining professionals’ Identification in the Workplace: the roles of organizational prestige, work-unit prestige, and professional status”, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 31, pp. 789-810. Ma, Z., Long, L., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J. and Lam, C.K. (2017), “Why do high-performance human resource practices matter for team creativity? The mediating role of collective efficacy and knowledge sharing”, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 34, pp. 565-586. Miao, R., Bozionelos, N., Zhou, W. and Newman, A. (2020), “High-performance work systems and key employee attitudes: the roles of psychological capital and an interactional justice climate”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, pp. 1-35, doi: 10.1080/09585192.2019. 1710722. Mishra, A.K. and Spreitzer, G.M. (1998), “Explaining how survivors respond to downsizing: the roles of trust, empowerment, justice, and work redesign”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 23, pp. 567-588. Nahapiet, J. and Ghoshal, S. (1998), “Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 23, pp. 242-266. Paauwe, J., Guest, D. and Wright, P. (2013), HRM and Performance: Achievements and Challenges, Wiley, Hoboken NJ. Pfeffer, J. (1998), The Human Equation, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Massachusetts. Postmes, T. (2003), “A social identity approach to communication in organizations”, in Haslam, S.A., van Knippenberg, D., Platow, M.J. and Ellemers, N. (Eds), Social Identity at Work: Developing Theory for Organizational Practice, Psychology Press, Philadelphia PA, Vols 81-98. Preacher, K.J. and Selig, J.P. (2012), “Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects”, Communication Methods and Measures, Vol. 6, pp. 77-98. Prieto, I.M. and Santana, M.P.P. (2012), “Building ambidexterity: the role of human resource practices in the performance of firms from Spain”, Human Resource Management, Vol. 51, pp. 189-212. Seibert, S.E., Wang, G. and Courtright, S.H. (2011), “Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: a meta-analytic review”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 96, pp. 981-1003. Shamir, B. (1990), “Calculations, values, and identities: the sources of collectivistic work motivation”, Human Relations, Vol. 43, pp. 313-332. Shamir, B., House, R.J. and Arthur, M.B. (1993), “The motivational effects of charismatic leaders: a selfconcept based theory”, Organization Science, Vol. 4, pp. 577-594. Spreitzer, G.M. (1996), “Social structural characteristics of psychological empowerment”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 39, pp. 483-504. Sterling, A. and Boxall, P. (2013), “Lean production, employee learning and workplace outcomes: a case analysis through the ability-motivation-opportunity framework”, Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 23, pp. 227-240. Tajfel, H. and Turner, J.C. (1986), “The social identity theory of inter-group behavior”, in Worchel, S. and Austin, L.W. (Eds), Psychology of Intergroup Relations, Nelson-Hall, Chicago. Takeuchi, R., Chen, G. and Lepak, D.P. (2009), “Through the looking class of a social system: crosslevel effects of high-performance work systems on employees’ attitudes”, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 62, pp. 1-30. Tofighi, D. and MacKinnon, D.P. (2015), “Monte Carlo confidence intervals for complex functions of indirect effects”, Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, Vol. 23, pp. 194-205. Ulrich, D. (2016), “HR at a crossroads”, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 54, pp. 148-164. Van Vugt, M. and Hart, C.M. (2004), “Social identity as social glue: the origins of group loyalty”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 86, pp. 585-598. HPWS in Chinese banks PR Wang, J., Cooke, F.L. and Huang, W. (2014), “How resilient is the (future) workforce in China? A study of the banking sector and implications for human resource development”, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 52, pp. 132-154. Wattoo, M.A., Zhao, S. and Xi, M. (2020), “High-performance work systems and work–family interface: job autonomy and self-efficacy as mediators”, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 58, pp. 128-148. Wood, R.E. and Bandura, A. (1989), “Social cognitive theory in organizational management”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14, pp. 361-384. Wright, P. and Haggerty, J.J. (2005), “Missing variables in theories of strategic human resource management: time, cause, and individuals”, Management Revue, Vol. 16, pp. 164-173. Wright, P. and Nishii, L. (2004), Strategic HRM and Organizational Behavior: Integrating Multiple Level Analysis, Paper presented at the 2004 What Next for HRM? Conference, Rotterdam. Xian, H., Atkinson, C. and Meng-Lewis, Y. (2019), “Guanxi and high performance work systems in China: evidence from a state-owned enterprise”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 30, pp. 2685-2704. Zacharatos, A., Barling, J. and Iverson, R. (2005), “High-performance work systems and occupational safety”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 90, pp. 77-93. Zhang, J., Akhtar, M.N., Bal, P.M., Zhang, Y. and Talat, U. (2018), “How do high-performance work systems affect individual outcomes: a multilevel perspective”, Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 9, pp. 1-13. Zhao, S.M., Zhang, J., Zhao, W. and Poon, T. (2012), “Changing employment relations in China: a comparative study of the auto and banking industries”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 23, pp. 2051-2064. Corresponding author Timothy Bartram can be contacted at: timothy.bartram@rmit.edu.au For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com