ACCA – APM

ADVANCED PERFORMANCE

MANAGEMENT

STUDY NOTES

CONTENTS

Chapter #

Chapter Name

Page #

Tips to Pass the Exam

1

Introduction to Strategic Management

01

2

Environmental Influences

11

3

Performance Hierarchy and Budgeting

20

ACCA Questions Part 1 (Solution key provided by ACCA)

48

4

Business Structure and Management Accounting

61

5

The Environment Issue & Risk and Uncertainty

73

6

Management Accounting Information

100

7

Management Report

116

ACCA Questions Part 2

132

8

Financial Performance Measure in the Private Sector

138

9

Divisional Performance Appraisal

155

10

Performance Management in Not-For-Profit Organisation

173

ACCA Questions Part 3

179

11

Non-Financial Performance Measurement

191

12

The Role of Quality in Performance Measurement

193

13

Human Resource Management Issues

206

14

Balance Scorecard and Performance Issues

224

15

Corporate Failure

237

ACCA Questions Part 4

248

TIPS TO PASS THE EXAM

Start the preparation early. Ideally plan to spend 2 hours daily on reading the notes and

study text .Otherwise you will be really frustrated and exhausted during exam days.

Try to understand the concepts and understand how they are applied

There is no substitute for practice. Need to be able to solve at least 5 past papers so that

you are able to comprehend the exam easily.

Try to solve the questions in exam room condition and record the time you are taking to

solve each question. Time Management is the key.

Never try to study on the last day before exam. This is your day to relax your brain before

the BIG DAY.

DO NOT WORRY, ALWAYS BE HAPPY! YOU HAVE THE POTENTIAL TO PASS THE EXAM

Intro to Strategic Management Accounting

APM – Study Notes

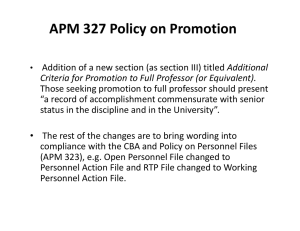

INTRODUCTION TO STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

Learning Objectives

Explain the role of strategic performance management in strategic planning and control

Discuss the role of performance measurement in checking progress towards the corporate objectives.

Compare planning and control between the strategic and operational levels within a business entity.

Discuss the scope for potential conflict between strategic business plans and short‐term localised

decisions.

Evaluate how models such as SWOT analysis, Boston Consulting Group, balanced scorecard, Porter’s

generic strategies and 5 Forces may assist in the performance management process.

Apply and evaluate the methods of benchmarking performance.

Assess the changing role of the management accountant in today’s business environment as outlined by

Burns and Scapens.

Page | 1

Intro to Strategic Management Accounting

APM – Study Notes

Strategic Management Accounting

Strategic management accounting is a form of management accounting in which emphasis is placed on

information about factors external to the organisation as well as on nonfinancial and internally‐generated

information.

Traditional management accounting is more concerned with the achievement of internal financial performance

targets (e. g. budget).

The aim of strategic management accounting is to provide information that is relevant to the process of strategic

planning and control.

The Strategic Planning Process

External analysis involves consideration of developments and circumstances outside the organisation which

may affect the organisation in the future. Relevant external factors include the law, politics, economics,

culture, technology and competition.

Internal analysis involves consideration of the strengths and weaknesses within the organisation. Relevant

internal factors include technical skills, know‐how, market reputation and liquidity.

SWOT analysis involves systematic consideration of the strengths and weaknesses of the organisation against

the background of the opportunities and threats it faces.

Gap analysis involves consideration of the difference between “where we are” and “where we want to be”

Page | 2

Intro to Strategic Management Accounting

APM – Study Notes

Level Of Management

Strategic management

Tactical management

Operational management

Management accounting system should provide information for strategic management, tactical management and

operational management

In many respects, strategic information, tactical information and operational information are concerned with the

same things (business plans and actual performance) but are provided in different amounts of detail and with

differing frequency. IT systems are used to provide this information

Strategic management is concerned with the development and execution of long term plans. Strategic

information needs are typically:

About the whole organisation and are summarised

Relevant to long term and forward looking

Likely to be prepared on an ad hoc basis and may be taken from external sources

Tactical management is concerned with efficient and effective use of resources in the implementation of medium

term plans. Tactical information needs are typically:

About individual departments and detailed

Relevant to medium term and a mix of backward and forward looking material

Likely to be prepared on a systematic and regular basis

Operational management is concerned with the day to day running of the business. Operational information

needs are typically:

‘task specific’ and very detailed, down to transaction level

Relevant to the very short term period and they are backward looking

Likely to be prepared regularly or continuously available on‐line

Role of Performance in Checking Progress

Vigilant and effective management systems ensure how well a business and its investment and expansion plans

succeed but many managers experience that as a business grows, they become more isolated from its operations.

Thus it is necessary to set up a system which can effectively manage the progress of a business. Here, performance

measurement systems play a major role.

A performance measurement system keeps track and updates the managers with all crucial information regarding

the current performance of the business. The system also facilitates in important task of setting up targets that

shape the strategies required by the business to grow.

Calculated measurements and target development may not be vital for small businesses, but for businesses that

are looking to expand and grow, these performance measurements provide essential controls. Good measurement

systems not only update on how different sectors of a business are working, but also equips managers to assess

factors that may affect the performance in any way, which in turn helps in managing performance more efficiently.

Page | 3

Intro to Strategic Management Accounting

APM – Study Notes

It is important to carefully select what exactly the system needs to measure. The priority here is to focus on

quantifiable factors that are clearly linked to the drivers of success in your business and your sector. These factors

are known as Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). The factors selected for assessment should preferably be

quantitative but not necessarily financial as even though financial measures seem decisive about the progress of a

business, some non‐financial factors are too important to ignore. E.g. If the success and performance of a business

depends on customer service, then the performance measurement system should assess the number of

complaints received instead of financial measurement.

Once the key indicators are identified, a way to measure them should be set up. Following this, performance

targets should be set up to present goal clarity for everyone. Businesses have strategic visions but it is not easy to

make them clear for everyone so it is more suitable to break down the vision into understandable yet crucial

targets so that it is easier for everyone to manage and achieve them. Through this strategy, daily operations

throughout the business are focused on the set targets.

It is of equal importance to effectively manage all the information being received through the system. Better

managed information about KPIs will be a more effective management tool that unorganized data.

Planning and Control between Strategic and Operational Level

One of the most underlying and important activities of any business is the planning. When planning all different

aspects of a business are taken into consideration including the vision, goals and objectives of the company. It

requires careful thinking and analyzing according to the predicted future of the business. Strategic planning occurs

at corporate level while operational planning includes all planning processes taking place at the functional level.

Strategic planning focuses on the long‐term objectives of the company while operational planning focuses on the

short‐term objectives. This definition of roles helps use resources in a better way to achieve all company goals.

Strategic control assesses whether the strategies set are being implemented and whether they are working out as

expected. Strategic control is “the critical evaluation of plans, activities, and results, thereby providing information

for the future action”. Operational control on the other hand assesses the daily operations and whether they are

in accordance to the set objectives. Wherever performance fails to meet the set standards, actions to correct them

are taken instantly. These actions usually involve training, motivation, leadership, discipline, or termination.

Conflict Between Strategic Business Plans and Short Term Decisions

Top‐down approaches to management may lead to conflict in decision making in organisations where

divisional autonomy & employee empowerment is practiced.

Routine Strategic planning is normally made annually or for a longer period while localised decision cannot

wait for subsequent strategic plan even if inconsistent with it

Decision flexibility of an organisation may become limited due to imposition of strategic business

plans. Organisation may not able to respond to changes in environment at the right time.

Rigid strategic plans discourages creativity in employee decisions

Page | 4

Intro to Strategic Management Accounting

APM – Study Notes

SWOT Analysis

The SWOT analysis combines the results of the environmental analysis and the internal appraisal into one

framework for assessing the firm's current and future strategic fit.

BCG matrix to assess business performance:

The Boston Consulting Group Matrix

There is a fundamental need for management to evaluate existing products and services in terms of their market

development potential, and their potential to generate profit. The Boston Consulting Group matrix, which

incorporates the concept of the product life cycle (PLC), is a useful tool which helps management teams to assess

existing and developing products and services in terms of their market potential. More importantly, the model can

also be used to assess the strategic position of SBUs, and in this respect it is particularly useful to those

organisations which operate in a number of different markets.

The matrix offers an approach to product portfolio planning. It has two controlling aspects, namely relative market

share (meaning relative to the competition) and market growth. Management must consider each product or

service that is marketed, and then position it on the matrix. This should be done for every product manufactured

or service provided, and management should then plot the position of competitors’ products and services on the

matrix in order to determine relative market share.

Page | 5

Intro to Strategic Management Accounting

APM – Study Notes

Stars

Stars are products which have a good market share in a strong and growing market. As a product moves into this

category it is commonly known as a ‘rising star’. While a market is strong and still growing, competition is not yet

fully established. Since demand is strong, and market saturation and over‐supply is not an issue, the pricing of such

products is relatively unhindered, and therefore these products generate very good margins. At the same time,

manufacturing overheads are minimised due to high volumes and good economies of scale. These are great

products, and worthy of continuing investment for as long as they have the potential to achieve good rates of

growth. In circumstances where this potential no longer exists, these products are likely to fall vertically in the

matrix into the ‘cash cow’ quadrant (‘fallen stars’), and their cash characteristics will change. It is therefore vital

that a company has ‘rising stars’ developing from its ‘problem children’ in order to fill the void left by the fallen

stars.

Problem children

‘Problem children’ have a relatively low market share in a high‐growth market, often due to the fact that they are

new products, or that they are yet to receive recognition by prospective purchasers. In order to realise the full

potential of problem children, management needs to develop new business prudently, and apply sound project

management principles if it is to avoid costly disasters. Gross profit margins are likely to be high, but overheads are

also high, covering the costs of research, development, advertising, market education, and low economies of scale.

As a result, the development of problem children can be loss‐making until the product moves into the rising star

category, which is by no means assured. This is evidenced by the fact that many problem children products remain

as such, while others become tomorrow’s ‘dogs’.

Cash cows

A cash cow has a relatively high market share in a low growth market, and should generate significant cash flows.

This somewhat crude metaphor is based on the idea of ‘milking’ the returns from a previous investment that

established good distribution and market share for the product. Activities to support products in this quadrant

should be aimed at maintaining and protecting their existing position, together with good cost management,

rather than aimed at growth. This is because there is little likelihood of additional growth being achieved.

Dogs

A‘dog’ has a relatively low market share in a low growth market. It might be loss making, and therefore have

negative cash flow. A common belief is that there is no point in developing products or services in this quadrant.

Many organisations discontinue ‘dogs’, but businesses that have been denied adequate funding for development

may find themselves with a high proportion of their products or services in this quadrant.

Limitations of the Boston Consulting Group matrix

The popularity of the matrix has diminished as more comprehensive models have been developed. Management

should exercise a degree of caution when using the matrix. Some of its limitations are detailed below:

The rate of market growth is just one factor in an assessment of industry attractiveness, and relative market

share is just one factor in the assessment of competitive advantage. The matrix ignores many other factors

that contribute towards these two important determinants of profitability.

There can be practical difficulties in determining what exactly ‘high’ and ‘low’ (growth and share) can mean in

a particular situation.

The focus upon high market growth can lead to the profit potential of declining markets being ignored.

The matrix assumes that each SBU is independent. This is not always the case, as organisations often take

advantage of potential synergies.

Page | 6

Intro to Strategic Management Accounting

APM – Study Notes

The use of the matrix is best suited to SBUs as opposed to products, or to broad markets (which might

comprise many market segments).

The position of ‘dogs’ is frequently misunderstood, as many of them play a vital role in helping SBUs achieve

competitive advantage. For example, dogs may be required to complete a product range and provide a

credible presence in the market. Dogs may also be retained in order to reduce the threat from competitors.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the Boston Consulting Group matrix provides a useful starting point in the

assessment of the performance of products and services and, more importantly, of SBUs.

EXAMPLE

Domestic Appliances Ltd (DAL) commenced trading in 1955, when it started to manufacture semi‐automatic

washing machines. From 1965, DAL expanded its product portfolio. Core products now include fully automatic

washing machines, dishwashers, and cookers. The market in domestic appliances is extremely competitive. DAL’s

principal competitor is the Jarvis Electrical Group (JEG), which has achieved the position of market leader in many

similar areas of the market. Other information is as follows:

1. JEG is the market leader in dishwashers, having 48% of the market. DAL has only 30% of the market.

Environmentalist pressure groups, concerned about water consumption, have caused a significant diminution

in the size of the market for dishwashers. However, the market remains profitable and this is expected to

continue.

2. DAL continues to manufacture washing machines using a process which uses new materials for each unit.

Legislation now requires that 35% of all materials used comprise recycled materials, which means that DAL will

no longer be able to sell its washing machines in certain markets.

3. Both DAL and JEG have invested very heavily in the manufacture of steam ovens. DAL has 12% of the new

market, while JEG has an 18% share of the new market.

4. DAL has recently produced a new washing machine, the Celeribus, which washes three times faster than any

other machine on the market. Market awareness of this machine is growing. The development costs of the

Celeribus were significant. At present the company is making heavy losses on production of this product.

Analyse the product portfolio of DAL using the Boston Consulting Group matrix.

Answer: Domestic Appliances Ltd

Page | 7

Intro to Strategic Management Accounting

APM – Study Notes

The steam oven appears to be a star at the moment since it has a relatively large market share in what is a high

growth market. The Celeribus is a problem child as it has generated losses to date, and has a relatively low market

share in a high‐growth market. The challenge facing the management of DAL is to convert the product into a star.

The dishwashers are cash cows as even though the rate of market growth is low, DAL has a relatively high market

share. Cash generated can be used not only to further develop stars but also problem children where it is deemed

appropriate. The washing machines will soon become dogs as they are no longer able to be sold in certain markets.

Porter’s Five Forces

Porter's Five Forces

1.

Power of suppliers

This force includes the ability of suppliers to change the cost of materials provided by them. It depends on the

number of accessible suppliers, how easily the business can shift between them and the power of control that

the suppliers have over the company.

2.

Power of buyers

This includes the power the buyers may exercise to lower the cost of a company’s products. It mainly depends

on the number of buyers and their importance for the company. It is also affected by the risk that the buyers

may face in switching to another company. The distribution and homogeneity of buyers are also important.

3.

Power of Competitive rivalry

The amount of competition that a company has is also important. This force expresses what a company’s own

standing is amongst rivals in the market.

4.

Power of Threat of substitution

This force highlights how easily the services or products of a company may be substituted or replaced by other

items or other brands. The more difficult it is to substitute the products, the stronger a company’s power is

while the easier it may be for buyers to access substitutes, the weaker a company’s position will be.

5.

Power of Threat of new entry

This aspect of the model focuses on how easy or difficult it is for a new company to enter the market as

competition. If it is easy, then existing businesses are at threat but if strong obstacles have been placed for

new competition, then the business has established a strong position.

Power of suppliers, power of buyers and power of competitive rivalry mainly discuss the existing position of the

company while power of threat of substitution and power of threat of new entry are associated with how strong a

business has kept itself against possible competition. The first three forces define how much progressive the

company can be while the other forces define how well that company can sustain itself in the long run.

Benchmarking

Benchmarking is:

‐ Data gathering of targets and comparators;

‐ Identifying relative levels of performance (and particularly include underperformance);

‐ Adopting the best practices that were identified to improve performance.

Page | 8

Intro to Strategic Management Accounting

APM – Study Notes

Benchmarking the reference enables a firm to:

‐ Meet industry standards by copying others,

‐ Challenge existing ways of doing things

‐ Assess current resources and competences

Advantages of benchmarking

‐ Assess existing resources

‐ Manager involvement

‐ Focus on improvement

‐ Sharing information

Disadvantages of benchmarking

‐ Too much focus on efficiency rather than effectiveness

‐ Assesses the present, not the future

‐ Targets and comparisons may not reveal the best practice (i.e. what, not why!)

‐ Useful information not freely available

Types of Benchmarking:

Internal benchmarking. Here performance is compared to an internally generated target. There has to be some

reference point f o r that target and it could be a target based o n last year‘s achievements or a target

based on another branch or subsidiary. It could be relatively easy to generate that target, but the problem is that

there is no guarantee that the target is appropriate. It could be either too hard or too easy; some sort of external

reference is needed.

External benchmarking. Here the performance is compared to that seen in other similar organisations. This gives

a better reference point, but the problem in implementing this is that often other organisations will be secretive

about their performance as their performance is commercially sensitive. They are therefore unlikely to cooperate

in providing internal data and only data from published financial statements will be available.

Best practice. This is more preferable as rather than randomly choosing an external, similar organisation, one

may choose the best one and build comparisons with the performance there. This causes ones organisational

ways to strive to get better as it seeks to match the performance found in the best practice. Once again the best

performing organisation may not cooperate in providing measurement data.

Burns and Scapen

The role of a managing accountant has effectively changed with progress in time and development of systems.

From a previous focus on financial control it is now more directed towards business support. Burns while studying

these changes noticed that previously accountants and operation managers were two separate entities who

reported to one senior manager but with progress in system, a new role of hybrid accountant who is also involved

in the operations while providing consultancy to managers is more commonly seen in companies. Scapens believes

that this change exists only because of the need for change.

Page | 9

Intro to Strategic Management Accounting

APM – Study Notes

There are three main forces for change: technology, management structure and competition.

1.

Technology:

There have been significant developments in information technology throughout the world in the past two

decades. Previously only the accountants were equipped with the ability to access, input data, manage and

interpret the IT systems and from the information develop financial reports for the management. Recently

with the advancement in management information systems (MIS), multiple users throughout the organisation

may perform all these tasks that previously only the accountant had the knowledge to handle. The value of

the management accountant has therefore reduced to just another user of the MIS.

2.

Management Structure:

The progression in management systems has also changed the responsibilities of an accountant. Due to the

increased autonomy of SBUs, the SBU managers are now more responsible for taking decisions that were

previously taken by the management accountant. The SBU managers are more associated with assessing

financial and non‐financial data and producing forecasts. The accountant however provides reports which link

and assess operational reports, financial consequences and the strategic outcomes desired alongside the SBU

reports.

3.

Competition:

As markets and knowledge have increased with time, businesses have started to focus strategically on the

competitive environment they are a part of. Competitive advantage is an important aspect for the progress of

businesses. This change has also altered the role of a management accountant. An accountant’s focus on

profit figures is now termed as short‐term while organisations now pay more attention to other measures that

may affect their long‐term performance. New and expanding companies pose a market threat for the old

companies, thus it is necessary that to survive in the competitive environment, companies make themselves

flexible, creative and more innovative to respond strongly to the increasing competitive threats.

Even though the role of the managing accountant has altered in these aspects, it is still beneficial and important.

The accountant now assists the SBU managers in retrieving more information effectively from the MIS, extracting

crucial information from the prepared reports and in developing performance measures assessing financial and

non‐financial aspects. The accountant now plays the role of a guide to the SBU managers ensuring that maximum

and efficient performance management is done which complements the goals and objectives of the company.

Page | 10

Environmental Influences

APM – Study Notes

ENVIRONMENTAL INFLUENCES

Learning objectives

Discuss the need to consider the environment in which an organisation is operating when assessing its

performance using models such as PEST and Porter's 5 forces, including areas:

Political climate

Market conditions

Page | 11

Environmental Influences

APM – Study Notes

Environmental Influences on Performance of Businesses

Once the objectives of the business are set, the organisation then needs to decide how to meet the objectives and

define the strategy. For that, it is important that the organisation considers what is going on in the outside world.

The business environment is the world in which the organisation operates.

This area will cover the following:

1. Macro Environment

2. The industry environment

3. Stakeholder’s Influence

4. Ethics

5. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

6. Government Influences

7. Risk & Uncertainty in external environment and How to manage it

Macro Environment

PEST ANALYSIS

It considers the following external factors:

1. Political Factors: e.g. change in government policy, tax incentives, instability of government etc.

2. Economic Factors: e.g. disposable income, inflation rates, employment rates, international trade etc.

3. Social Factors: Demography (average age, ethnicity, family structure, geography, culture, lifestyle etc.

4. Technological Factors: e.g. awareness of stakeholders about technology, new products and services become

available, new media for communication with customers etc.

All above factors are interlinked

All PEST factors help an organisation to identify its threats and opportunities in the external environment

which can impact performance

ILLUSTRATION

Speedy Eat is the world’s largest and best‐known food service retailing group with more than 30,000 ‘fast‐food’

outlets in over 120 countries. Currently half of its restaurants are in the USA, where it first began 50 years ago,

but up to 1,000 new restaurants are opened every year worldwide. Restaurants are wholly owned by the group

(it has previously considered, but rejected, the idea of a franchising of operations and collaborative

partnerships).

As market leader in a fiercely competitive industry, Speedy Eat has strategic strengths of instant global brand

recognition, experienced management, site development expertise and advanced technological systems.

Speedy Eat’s basic approach works as well in Kandy or Kuala Lumpur as it does in Kansas: although the products

are broadly similar, menus are modified to reflect local tastes. Analysts agree that it continues to be profitable

because it is both efficient and innovative.

The group’s vision is to be ‘the world’s favourite’ through service, cleanliness and value, and it is following three

main strategies:

a. To achieve profitable growth by building on key strengths.

b. To ‘delight’ every customer in every restaurant.

Page | 12

Environmental Influences

c.

APM – Study Notes

To be a good employer in each community in which it has a restaurant. (Despite this, some critics claim

staff are mainly unskilled and lowly paid.)

Speedy Eat’s future plans are to maximize global opportunities and continue to expand markets. Speedy Eat has

long recognized that the external environment can be very uncertain and consequently does not move into new

locations or countries without first undertaking a full investigation.

You are part of a strategy steering team responsible for investigating the key factors concerning Speedy Eat’s

entry for the first time into the restaurant industry in the Republic of Borderland.

Required:

(a)

Justify the use of a PEST framework to assist your team’s environmental analysis for the Republic of

Borderland.

(8 marks)

(b)

Discuss the main issues arising from applying this framework.

(12 marks)

(20 Marks)

Answer

(a) Using a PEST analysis to assist the environmental analysis

PEST analysis examines the broad environment in which the organisation is operating. PEST is a mnemonic

which stands for Political, Economic, Social and Technological factors. These are simply four key areas in

which to consider how current and future changes affect the business. Strategies can then be developed

which address any potential opportunities and threats identified.

In entering a new overseas market, an environmental analysis is important to help the organisation

understand the factors specific to that market so that the specific opportunities and threats posed can be

assessed and appropriate action taken.

It is a useful tool for the following reasons:

1. It ensures completeness

The majority of issues relevant to an organisation will be covered under one of the four areas of PEST

analysis. By reviewing all four areas, Speedy Eat can be sure that it has done a full and complete

analysis of the broad environment.

2.

All four elements are relevant to examining new markets

Political/legal

Each new country entered will have different political systems and laws. Speedy Eat will need to

understand these differences to ensure that they operate within the law in Borderland. They will also

want to ensure that there is political stability within the country which will ensure long‐term viability of

the new operations.

Page | 13

Environmental Influences

APM – Study Notes

Economic

Economies are different in different parts of the world. Understanding the local economy in Borderland

and how it is expected to develop enables Speedy Eat to assess the potential within that market as well

as any economic issues which they need to consider.

Social

Each country will have its own cultural differences, and Speedy Eat can change how they operate

depending on Borderland’s culture. Speedy Eat has already shown its willingness to change for each

country’s different tastes and will want to do so in Borderland too.

Technological

Each country has a different level of technological expertise and experience. Speedy Eat might need

to change processes to accommodate local systems, or implement training programs for staff

unfamiliar with their technology.

3.

It is a well‐known tool which is easy to understand and use

PEST analysis is a very simple tool that does not require detailed understanding. This means

that it is easy to use by the team and simple for Directors to analyse and understand.

(b) Main issues arising from applying the framework

Various issues which Speedy Eat will need to consider include:

Political/legal factors

Government grants

Some countries may have grants available for investment in the country. Considering the requirements

to gain such grants may enable Speedy Eat to make use of these.

Political stability

Given Speedy Eat’s worldwide penetration (over 120 countries) it is likely that Borderland is in a

developing region which may be more politically unstable than many countries in which they currently

operate. This may affect the long‐term potential in the market.

Regulation on overseas companies

There may be regulation on how overseas companies can operate in the market. In China, for instance,

it is common for joint ventures with local companies to be a prerequisite for western companies

entering the market.

Employment legislation

Each country will have different employment legislation e.g. health and safety, minimum wages,

employment rights. Speedy Eat may have to change internal processes from the US model to stay

within this legislation within Borderland. Being a good employer is also one of Speedy Eat’s specific

strategies.

Tax legislation

Tax laws will impact the profits available for distribution to the group. High tax levels may discourage

Speedy Eat from entering the market.

Tariffs and other barriers to trade

Tariffs may be imposed on imports into Borderland. This may put Speedy Eat at a significant

disadvantage compared with local competitors if they aim to import a significant number of items

(unlikely on food items, more likely on clothing, fittings etc.).

Page | 14

Environmental Influences

APM – Study Notes

Economic factors

Things to consider include:

Economic prosperity

The more prosperous the nation the more money people will have to invest in ‘fast‐food’. Examining

the current and likely future prosperity enables the organisation to understand the potential of this

market and the likely future investment required.

Interest rates

This affects the cost of borrowing within Borderland. If high it may mean overseas funding is

necessary. A big differential between interest rates in Borderland and the US is also likely to cause

instability in the exchange rate (see below).

Interest rates also affect the availability of money for the people of the country. Low interest rates

mean more disposable income to spend increasing the potential for Speedy Eat.

Exchange rates

Speedy Eat will be affected by exchange rates for items they export to Borderland (clothing, fittings).

An unfavorable movement in exchange rates could make exporting to Borderland expensive and

reduce profitability. It can also affect the value of profits when converted back to US dollars.

Position in economic cycle

Different countries are often at different positions in the economic cycle of growth and recession. The

current position of Borderland will affect the current prosperity of the nation and the potential for

business development for Speedy Eat.

Inflation rates

High inflation rates create instability in the economy which can affect future growth prospects. They

also mean that prices for supplies and prices charged will regularly change and this difficulty would

need to be considered and processes implemented to account for this.

Social factors

Things to consider include:

Brand reputation/anti‐Americanism

As a global brand, the reputation of Speedy Eat might be expected to have reached Borderland. If not,

more marketing will be required. If it has, the reputation will need to be understood and the

marketing campaign set up accordingly.

This is particularly relevant given the anti‐Americanism which is prevalent currently in some countries.

Speedy Eat may have a significant hurdle to climb to convince people to eat there if this is the case in

Borderland.

Cultural differences

Each country has its own values, beliefs, attitudes and norms of behaviours which means that people of

that country may like different foods, architecture, music and so on, in comparison with US

restaurants. By adapting to local needs Speedy Eat can ensure it wins local custom and improve its

reputation.

Different cultures also need to be considered when employing people, especially given the importance

to Speedy Eat of employee relations. People might have different religious needs to be met or may

dislike being given autonomy so the management style needs changing.

Language problems

Different local languages can create problems, firstly in communication with staff. Secondly, product

names need to be considered to ensure they are acceptable in the local language. General Motor’s

Nova suggested that ‘it won’t go’ in Spanish, for example.

Page | 15

Environmental Influences

APM – Study Notes

Technological factors

Speedy Eat may need to train people in the use of their technologies if the local population is

unfamiliar with them, e.g. accounting systems or tills. In addition, technology might have to be adapted

to work in local environments, such as different electrical systems.

The Industry Environment

Porter’s Five Forces Model

The use of Porter’s Five Forces Model (see Figure 1) helps identify the sources of competition in an industry or

sector.

The model has similarities with other tools for environmental audit, such as political, economic, social, and

technological (PEST) analysis, but should be used at the level of the strategic business unit, rather than the

organisation as a whole. A strategic business unit (SBU) is a part of an organisation for which there is a distinct

external market for goods or services. SBUs are diverse in their operations and markets so the impact of

competitive forces may be different for each one.

Five Forces analysis focuses on five key areas: the threat of entry, the power of buyers, the power of suppliers, the

threat of substitutes and competitive rivalry.

Page | 16

Environmental Influences

APM – Study Notes

THE THREAT OF ENTRY

This depends on the extent to which there are barriers to entry. These barriers must be overcome by new entrants

if they are to compete successfully. Johnson et al (2005), suggest that the existence of such barriers should be

viewed as delaying entry and not permanently stopping potential entrants. Typical barriers are detailed below.

Economies of scale

For example, the benefits associated with volume manufacturing by organisations operating in the automobile and

chemical industries. Lower unit costs result from increased output, thereby placing potential entrants at a

considerable cost disadvantage unless they can immediately establish operations on a scale that will enable them

to derive similar economies.

The capital requirement of entry

These vary according to technology and scale. Certain industries, especially those which are capital intensive

and/or require very large amounts of research and development expenditure, will deter all but the largest of new

companies from entering the market.

Access to supply or distribution channels

In many industries, manufacturers enjoy control over supply and/or distribution channels via direct ownership

(vertical integration) or, quite simply, supplier or customer loyalty. Potential market entrants may be frustrated by

not being able to get their products accepted by those individuals who decide which products gain shelf or floor

space in retailing outlets. Retail space is always at a premium and untried products from a new supplier constitute

an additional risk for the retailer.

Supplier and customer loyalty

A potential entrant will find it difficult to gain entry to an industry where there are one or more established

operators with a comprehensive knowledge of the industry, and with close links with key suppliers and customers.

Cost disadvantages independent of scale

Well‐established companies may possess cost advantages which are not available to potential entrants irrespective

of their size and cost structure. Critical factors include proprietary product technology, personal contacts,

favourable business locations, learning curve effects, favourable access to sources of raw materials, and

government subsidies.

Expected retaliation

In some circumstances, a potential entrant may expect a high level of retaliation from an existing firm, designed to

prevent entry – or make the costs of entry prohibitive.

Government regulation

This may prevent companies from entering into direct competition with nationalised industries. In other scenarios,

the existence of patents and copyrights afford some degree of protection against new entrants.

Differentiation

Differentiated products and services have a higher perceived value than those offered by competitors. Products

may be differentiated in terms of price, quality, brand image, functionality, exclusivity, and so on. However,

differentiation may be eroded if competitors can imitate the product or service being offered and/or reduce

customer loyalty.

Page | 17

Environmental Influences

APM – Study Notes

THE POWER OF BUYERS

The power of the buyer will be high where:

There are a few, large players in a market. For example, large supermarket chains can apply a great deal of

price pressure on their potential suppliers. This is especially the case where there are a large number of

undifferentiated, small suppliers, such as small farming businesses supplying fresh produce to large

supermarket chains

The cost of switching between suppliers is low, for example from one haulage contractor to another

The buyer’s product is not significantly affected by the quality of the supplier’s product. For example, a

manufacturer of foil and cling film will not be affected too greatly by the quality of the spiral‐wound paper

tubes on which their products are wrapped

Buyers earn low profits

Buyers have the potential for backward integration, for example where the buyer might purchase the supplier

and/or set up in business and compete with the supplier. This is a strategic option which might be selected by

a buyer in circumstances where favourable prices and quality levels cannot be obtained

Buyers are well informed. For example, having full information regarding availability of supplies.

THE POWER OF SUPPLIERS

The power of the seller will be high where (this tends to be a reversal of the power of buyers):

There are a large number of customers, reducing their reliance upon any single customer

The switching costs are high. For example, switching from one software supplier to another could prove

extremely costly

The brand is powerful (BMW, McDonalds, Microsoft). Where the supplier’s brand is powerful then a retailer

might not be able to operate a particular brand in its range of products

There is a possibility of the supplier integrating forward, such as a brewery buying restaurants

Customers are fragmented so that they have little bargaining power, such as the customers of a petrol station

situated in a remote location.

THE THREAT OF SUBSTITUTES

The threat of substitutes is higher where:

There is product‐for‐product substitution, e.g. for fax and postal services

There is substitution of need. For example, better quality domestic appliances reduce the need for

maintenance and repair services. The information technology revolution has made a significant impact in this

particular area as it has greatly diminished the need for providers of printing and secretarial services

There is generic substitution competing for disposable income, such as the competition between carpets and

flooring manufacturers.

COMPETITIVE RIVALRY

Competitive rivalry is likely to be high where:

There are a number of equally balanced competitors of a similar size. Competition is likely to intensify as one

competitor strives to attain dominance over another

The rate of market growth is slow. The concept of the life cycle suggests that in mature markets, market share

has to be achieved at the expense of competitors

There is a lack of differentiation between competitor offerings because, in such situations, there is little

disincentive to switch from one supplier to another

Page | 18

Environmental Influences

APM – Study Notes

The industry has high fixed costs, perhaps as a result of capital intensity, which may precipitate price wars

and hence low margins. Where capacity can only be increased in large increments, requiring substantial

investment, then the competitor who takes up this option is likely to create short‐term excess capacity and

increased competition

There are high exit barriers. This can lead to excess capacity and, consequently, increased competition from

those firms effectively ‘locked in’ to a particular marketplace.

In summary, the application of Porter’s Five Forces model will increase management understanding of an industrial

environment which they may want to enter.

EXAMPLE 1

Kleen‐up plc, which provides factory cleaning services, is considering a strategic decision to set up industrial

launderettes in order to enter the market for cleaning industrial work‐wear in the country of Eajland. Map the

following eight points onto the five forces model:

1. A government grant, equal to 95% of the start‐up costs, will be paid to any organisation setting up an

industrial launderette.

2. Disposable work‐wear is available on a nationwide basis from a distributor of imported products.

3. A large number of businesses spend large amounts of money on cleaning employees’ work‐wear each

week.

4. There are very few high quality launderettes capable of cleaning industrial work‐wear to a satisfactory

standard.

5. Health and Safety legislation in Eajland encourages the use of launderettes by businesses.

6. Other launderettes within the community regularly offer free cleaning, or high discounts on the cleaning of

clothing items.

7. The number of industrial firms setting up in Eajland is increasing by 10% per annum.

8. The market in the cleaning of industrial work‐wear in Eajland is relatively new, and is projected to grow

rapidly.

Answer

1. A government grant, equal to 95% of the start‐up costs, will be paid to any organisation setting up an

industrial launderette. threat of entry – low barriers to entry

2. Disposable work‐wear is available on a nationwide basis from a distributor of imported products. product‐

for‐product substitution

3. A large number of businesses spend large amounts of money on cleaning employees’ work‐wear each

week. high bargaining power of buyers

4. There are very few high quality industrial launderettes capable of cleaning industrial work‐wear to a

satisfactory standard. high bargaining power of suppliers

5. Health and Safety legislation in Eajland encourages the use of industrial launderettes by businesses. Threat

of entry reduced by legislation

6. Other launderettes within the community regularly offer free cleaning, or high discounts on the cleaning of

clothing items. Threat of entry – differentiation

7. The number of industrial firms setting up in Eajland is increasing by 10% per annum. bargaining power of

buyers

The market in the cleaning of industrial work‐wear is relatively new, and is projected to grow rapidly.

Page | 19

Performance Hierarchy & Budgets

APM – Study Notes

PERFORMANCE HIERARCHY & BUDGETS

Learning objectives

Discuss how the purpose, structure and content of a mission statement impacts on performance

measurement and management.

Discuss how strategic objectives are cascaded down the organisation via the formulation of subsidiary

performance objectives.

Apply critical success factor analysis in developing performance metrics from business objectives.

Identify and discuss the characteristics of operational performance.

Discuss the relative significance of planning activities as against controlling activities at different levels in

the performance hierarchy.

Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of alternative budgeting models and compare such techniques as

fixed and flexible, rolling, activity based, zero based and incremental.

Evaluate different types of budget variances and how these relate to issues in planning and controlling

organisations.

Page | 20

Performance Hierarchy & Budgets

APM – Study Notes

Performance Hierarchy

1. At the top of the hierarchy is the mission statement

2. The mission statement provides a framework for the setting of strategic objectives

3. Strategic objectives form a basis for the setting of tactical plans such as annual budgets

4. Operating plans and targets derived from tactical plans

Mission Statement

Mission statement

A clear expression of the reason why an organisation is in existence and what it is seeking to achieve

Not all organisations have formal statements

The Content varies – common elements are:

A statement of the purpose of the organisation

A statement of its broad strategy for achieving its purpose

A statement of the values and culture of the organisation.

Usefulness of a mission statement

It provides a guide to stakeholders

Aids formulation of business strategy (can be used to screen proposed strategies)

Can establish corporate culture

Strategic Objective And Cascading Down The Organisation

Every business needs to have set strategic objectives to develop a proper framework of plan which supports the

vision of each area of an organisation. Strategic objectives include a vision ranging from3 to 5 years which would

have long term effect of the performance of the company. They have a broad perspectives which include financial,

customer, operational processes, and staff development.

When developing strategic objectives, there are a few perspectives that should be kept in mind to help lay a more

efficient framework. The financial perspective guides according to the shareholders’ and stakeholders’

expectations for financial and social outcomes of the company. The customer perspective helps the planners

decide what value should be provided to the customers. The operations perspective involves the processes that

must be made efficient to provide and deliver value products and services. The people perspective helps define

the processes, skills, structures and expertise an organisation must have.

A framework plan should preferably consist of 4‐6 objectives as less than 4 objectives give the impression of an

incomplete plan while greater than 6 objectives give the impression of unachievable tasks.

Page | 21

Performance Hierarchy & Budgets

APM – Study Notes

Cascading to Create Annual Aligned Goals

Following strategic objective development, it is necessary to be able to communicate them to the rest of the

organisation in order to achieve them. For this purpose, aligned annual goals are formulated to help all areas

accomplish the yearly requirements and in turn long‐term objectives efficiently. It is important to communicate to

the employees that the aligned annual goals are of the highest priority at the present and should be achieved

actively in order to reach the actual long‐term objectives.

They aligned annual goals of a company might look something like:

150K in unrestricted grants and $1M total funding

Always have at least 90 days of cash on hand

25% of sales from outside of California and 15% growth in California

Quality control process for our services

Meaningful employee recognition program in place

All departments know the “customer” they serve

When constructing goals, it is important to make sure that the goal is clear and easily communicated. The goal

should clearly explain what it aims to achieve, who is responsible for achieving it and what the deadline is to

achieve it.

Once strategic objectives have been constructed and aligned annual goals are formulated in accordance to those

objectives, it is required that they are brought together and a framework of the strategic plan is defined using

them. Through this strategy, long term objectives can be achieved by fulfilling the annual goals which can further

be supported by short term goals.

Page | 22

Performance Hierarchy & Budgets

APM – Study Notes

Critical Success Factor (CSF)

Factors that are critical to the success of an organisation and the achievement of its overall objectives

Key areas where targeted performance must be achieved;

Failure to meet targets for any CSF will mean failure to achieve long‐term targets and objectives

Each CSF requires a performance measure (key performance indicators or KPIs)

Critical success factors must be in line with the mission or corporate strategy of the business

Managing Critical Success Factors

1. Identify CSF

2. Measure CSF using (KPIs‐ Key performance indicators)

3. Target setting (Benchmark)

4. Identify the problem areas

5. Take corrective actions

6. Re‐measure KPI

Characteristics of Operational Performance

There are five main operational performance objectives: speed, quality, costs, flexibility, and dependability.

Speed

Page | 23

Performance Hierarchy & Budgets

APM – Study Notes

This objective assesses the speed with which a company can provide services and products to the consumers. It

includes all concerns that involve time e.g. how fast research can be done and products developed and how much

time it is taken from the start of the manufacturing process to the delivery of the products.

Quality

Quality of a product measures how well a product falls within the general requirements expected of the product. It

also assesses the reliability, durability and performance of the products. The amount of trust customers put into

the value of the products and how easily it can be repaired also define its quality.

Costs

This part of operational performance measures how much the cost of one unit may differ with respect to different

factors which may include volume and variety of the manufactured products. Products that feature a greater

variety tend to sport lower volumes and higher unit costs and vice versa. Through this, the costs and profits of the

products are decided.

Flexibility

Flexibility means how well product lines and products adjust to new demands. A flexible product adjusts in

accordance to the speed objective as well adapting to the market demands and delivery demands. To be able to

produce varying quality products in accordance to all requirements is the true meaning of flexibility.

Dependability

This objective includes assessing how much customers can depend on a company with respect to quality, service,

delivery time and costs. When a company provides good quality and services over a long period of time, it

becomes accepted as dependable.

BUDGETING (PURPOSE)

Purpose

Planning

Control

Communication

Co‐ordination

Explanation

A business needs to map ahead how it intends to operate in its environment. By

planning, management are forced to think and plan ahead as to how their business

is to operate, compete and grow.

By setting up a budget, a business uses standard cost cards. These set out the

expected sales price to achieve for goods sold, the expected resources that each

unit should consume and at what cost.

The budget is a formal part of the businesses reporting channels, often reflecting the

hierarchy of responsibility in the business. The budget may reflect and indeed

dictate the intended activities of the business. E.g. Senior management may set

targets for junior management to achieve better in terms of sales volume and

activity through the budget.

In large organisations especially, it is hard to ensure that all departments are

working towards common aim and objectives. For example, it is critical that if the

sales department is aiming to sell 1,000 units, it must be communicated through the

budget to the production department so that it knows how many units they are

expected to make. The production department will need (via budgets) to

communicate with the purchasing department to ensure that enough components

are purchased to cope with the production of 1,000 units and so on.

Page | 24

Performance Hierarchy & Budgets

Evaluation

Motivation

Authorisation

APM – Study Notes

Budgeting can allow the business to have a benchmark in order to assess the

performance of individual departments, functions or indeed managers within a

business.

If a departmental manager is given a budget, it acts as a target for that manager to

aspire to. If by achieving that budget the manager is rewarded, the budget acts as an

incentive to the manager. If all managers achieve their targets (and are rewarded for

doing so) then the business as a could efficiently achieve its aims and objectives.

Budgets can act as a tool to authorise junior management to undertake a particular

action. For example if Manager X has $45,000 included in their budget to recruit two

new members of staff, then the manager has in essence been authorised to

undertake the recruitment and spend a set amount of money doing so.

Participation in budget

Top‐down approach

It is a budget, which is set without allowing the ultimate budget holders to have the opportunity to participate in

the budgeting process. It is also called ‘imposed’ budget or non‐participative.

Features

Senior management prepares budgets

It is imposed on junior management

It is quicker than bottom up approach

Time saving

The time when imposed budgets are effective

New organisation

Small businesses

In period of economic hardship

At a time when operational personnel have a lack of budgeting skills

At a time when different organisation’s units require precise coordination

Advantages

Strategic plans are incorporated in budgets

Increased coordination between plans and long‐term objectives of the division

Involvement of senior management in operational decisions

Decreased input from inexperienced employees

Time saving

Disadvantages

Low employees morale (hard for people to be motivated to achieve targets set by someone else)

Acceptance of organisational goals & objectives could be limited

Operational managers are likely to have a better understanding of day by day operations

Unachievable budgets (may be for local operations)

Page | 25

Performance Hierarchy & Budgets

APM – Study Notes

Method of budgets

Fixed budget

A Fixed Budget is designed to remain unchanged irrespective of the volume of output or turnover attained.

Flexible budget

A flexible budget is a budget which is prepared at the start of the year at more than one activity level and can be

flexed to the actual activity level for variance analysis. For preparing flexible budget cost behaviour of all elements

should be known and all cost should be classified as fixed or variable.

Example

Zenith Ltd. manufactures and sells a single product; Alpha. Operational capacity of plant is 100,000 units of

Alpha a year but due to plant deterioration it is now expected that it can only produce 80,000 units of Alpha a

year. A budget is prepared at 80% and 90% plant capacity.

Sales

Costs:

Direct material

Direct labour

Production overheads

Selling & distribution overheads

Net income

80%

$

640,000

90%

$

720,000

96,000

128,000

210,000

50,000

________

156,000

________

108,000

144,000

230,000

50,000

________

188,000

________

Actual production for the period was 68,000 units of Alpha. Actual costs and revenue for the period were as

follows:

$

Sales

680,000

Costs:

Direct material

105,400

Direct labour

132,600

Production overheads

213,200

Selling & distribution overheads

60,000

________

Net income

168,800

________

There was no opening and closing stock. Sales price is fixed.

Required:

You are required to prepare a flexed budget and compare the actual results with the flexed budget.

Page | 26

Performance Hierarchy & Budgets

APM – Study Notes

Incremental budgets

An incremental budget starts with the previous period’s budget or actual results and adds (or subtracts)an

incremental amount to cover inflation and other known changes.

It is suitable for stable businesses, where costs are not expected to change significantly. There should be good

cost control and limited discretionary costs.

Advantages

Disadvantages

Quickest and easiest method.

Builds in previous problems and inefficiencies

Suitable if the organisation is stable and historic figures

are acceptable since only the increment needs to be

justified.

Uneconomic activities may be continued. E.g. the firm

may continue to make a component in‐house when it

might be cheaper to outsource.

Managers may spend unnecessarily to use up their

budgeted expenditure allowance this year, thus

ensuring they get the same (or a larger) budget next

year.

Zero Based Budgeting

ZBB are an improvement of incremental budgets.

ZBB involves the simple idea of preparing a budget from a ‘zero base’ each period (like a ‘clean sheet of paper’!).

There is no expectation that current activities should continue from one period to the next. ZBB is unlikely to be

used frequently in manufacturing industries where the manufacturing processes are likely to be identical or very

similar year‐on‐year. Therefore, there is little point in redrafting the entire budget from scratch. The

manufacturing process largely dictates how costs are incurred.

ZBB is normally found in service industries where costs are more likely to be discretionary. There is more flexibility

to adapt the service provided from one period to the next to better fit in with customer expectation.

Suitability

Fast moving businesses and industries

Public sector organisations such as local authorities

Discretionary costs such as research and development (R&D).

Explanation

SKANS could in one year provide students with:

Tuition Days

Revision Days

Study Text Book

Revision Kit

Study Notes

Revision Notes

Practice Exams

Page | 27

Performance Hierarchy & Budgets

APM – Study Notes

All of these products and services will have their own associated costs. If however student demand is such, or

there is a major selling opportunity, SKANS can undertake ZBB and decide to alter their course structure and

provision dramatically.

For example SKANS can alter course structure in length and timings, change its course material, run courses

from new locations, offer new products (such as video lectures and discussion board) etc. As a service business

it is much easier to adapt the mode of delivery of its ‘product’ and previous budgets will bear little resemblance

to future activities (i.e. there is little scope for incremental budgeting).

Organisations considering using ZBB would need to consider the four basic steps to follow:

1. Prepare decision packages

Identify all possible services (e.g. courses offered by SKANS) and levels of service (e.g. length of course) that

may be provided and then cost each service or level of service. These are known individually as decision

packages.

Explanation

SKANS can consider a wide variety of methods of delivering courses. Each possible service or level of service

(decision package) needs to be included in the cost (e.g. printing cost of a textbook) and assessed for the likely

benefit (e.g. number of students attracted to SKANS courses) it will bring to the organisation.

2.

Rank the decision packages

Each decision packages is ranked in order of importance, starting with the mandatory requirements of a

department.

Explanation

SKANS has to provide a tuition and revision course for each paper. These are essential services which must be

funded by the business. Other decision packages can then be considered. SKANS may then consider updating its

course study notes as being the next most ‘value‐added’ activity. After that the next most important decision

packages are ranked. This forces the management to consider carefully what their aims are for the coming year

and importantly their priorities.

3.

Funding

Identify the level of funding that will be available to the business. This may relate to the amount of cash SKANS

has available, its lines of credit with its bankers etc.

4.

Utilise

These funds are then used up in the order of the ranking at step 2, until exhausted. The highest ranked

decision packages are financed. Allocation of funding continues until it is exhausted (say at the 12th ranked

decision package). Any lower ranking decision packages, being less of a priority to the business may not be

funded and are ‘shelved’ (e.g. the 13th ranked decision package onwards). If however more funding becomes

available, then the business can select the next decision package (the 13th) and undertake that decision

package.

The key with ZBB is that it focuses the business’s attention on where its money must be spent to the best effect. It

helps the business to prioritise where it should invest, without being dependent on a previous year’s budget (as

with incremental budgeting). It is a considered allocation of resources.

Page | 28

Performance Hierarchy & Budgets

APM – Study Notes

Advantages of Zero Based Budgets (ZBB) (as opposed to incremental budgeting)

1. Emphasis on future need instead of past actions. ZBB focuses on future plans and is not ‘swayed’ by what was

in last year’s budget. The strategies that worked well in the past are no guarantee of future success.

2. Eliminates past errors that may be perpetuated in an incremental analysis. Any inefficiencies or mistakes in

previous budgets under incremental budgeting are perpetuated (and often magnified) in future budgets. ZBB

eliminates these errors (although the possibility of new errors being introduced cannot be eliminated).

3. A considered allocation of resources. The business does not automatically carry on the projects that they have

always performed in the past.

4. Encourages cost reduction. The business may continue projects that it has undertaken in the past, but a close

review of costs will have been undertaken.

Disadvantages of Zero Based Budgets (ZBB)

1. Can be costly and time consuming. ZBB techniques will take a lot of time in terms of training managers in the

required techniques and more time and effort in preparing each decision package.

2. May lead to increased stress for management. Managers may become nervous that their decision packages

may not be accepted. It is possible that the manager may worry about redundancy if they have too few

decision packages that are approved. It is conceivable that managers may put forward unrealistic decision

packages to ensure that they are accepted.

3. Only really applicable to a service environment. It is not applicable in a manufacturing environment where the

production process dictates how the production is undertaken.

4. May ‘re‐invent’ the wheel each year. It is quite conceivable that if ZBB is undertaken each year, the same

decision packages are accepted. This is an inefficient approach to budgeting.

5. May lead to lost continuity of action and short‐term planning. The business may alter its activities and plans

year by year, causing a lack of consistency and possible drift from its strategic aims. For example if SKANS

decided one year to run its courses entirely online and the next year purely in the classroom, it would

antagonise students and have serious repercussions for resource allocation and usage (e.g. having to find and

kit out premises and recruit tutors at a very short notice).

Rolling Budget

A rolling budget is one that is kept continually up‐to‐date by revising at the end of each month and also adding a

further month.

For example, on 1 January 2008 prepare a budget for the whole year upto 31 December 2008.

At the end of January 2008, revise the budget for the remaining 11 months of 2008 (in the light of what happened

in January), and also prepare a budget for January 2009.

In this way there is always a budget for the coming 12 month period.

The benefits of rolling budgets are that they are likely to be more accurate, and also the work‐load of budgeting is

spread throughout the year and becomes part of the normal job – again leading to more accurate budgeting.

Page | 29

Performance Hierarchy & Budgets

APM – Study Notes

Example

A company uses rolling budgeting and has a sales budget as follows:

Q1

Q2

Q3

($)

($)

($)

Sales

125,750

132,038

138,640

Q4

($)

145,572

Total

($)

542,000

Actual sales for Quarter 1 were $123,450. The adverse variance is fully explained by competition being more intense

than expected and growth being lower than anticipated.

The budget committee has proposed that the revised assumption for sales growth should be 3% per quarter for Quar

ters 2, 3 and 4.

Required:

Update the budget figures for Quarters 2–4 as appropriate

Solution

ANSWER

The revised budget should incorporate 3% growth starting from the actual sales figure of Q1.

Sales

Q2 ($)

127,154

Q3 ($)

130,969

Q4 ($)

134,898

Workings

Q2: Budget = $123,450 × 103%

Q3: Budget = $127,154 × 103%

Q4: Budget = $130,969 × 103%

Example

ABC is a high growth non‐alcoholic drinks company, currently it uses a system of incremental budgeting. ABC

has been receiving complaints from customers about late deliveries and poor quality control. ABC's managers

have explained that they are working hard within the budget and capital constraints imposed by the board and

have expressed a desire to be less controlled. ABC's incremental budget for the current year is given below. You

can assume that cost of sales and distribution costs are variable and administrative costs are fixed.

Revenue

Cost of sales

Gross profit

Distribution costs

Administration costs

Operating profit

Q1

$'000

8,760

4,818

3,942

789

2,107

1,046

Q2

$'000

8,979

4,939

4,040

808

2,107

1,125

Q3

$'000

9,204

5,062

4,142

829

2,107

1,206

Q4

$'000

9,434

5,189

4,245

849

2,107

1,289

Total

$'000

36,377

20,008

16,369

3,275

8,428

4,666

Page | 30

Performance Hierarchy & Budgets

APM – Study Notes

The actual figures for Quarter 1 (which has just completed) are:

$'000

Revenue

8,966

Cost of sales

4,932

Gross profit

4,034

Distribution costs

807

Administration costs

2,107

Operating profit

1,120

On the basis of the Q1 results, sales volume growth of 3% per quarter is now expected.

Required

Recalculate the budget for ABC using rolling budgeting and assess the use of rolling budgets in this context.

ANSWER

A rolling budget is one where the budget is kept up to date by adding another accounting period when the most

recent one expires. The budget is then rerun using the new actual data as a basis.

For ABC, with its quarterly forecasting, this would work by adding another quarter to the budget and then

rebudgeting for the next four quarters.

Rolling budgets are suitable when the business environment is changing rapidly (which is likely to be the case

here) or when the business unit needs to be tightly controlled (which may not be valid here since managers are

complaining about control).

The new budget at ABC would be:

Revenue

Cost of sales

Gross profit

Distribution costs

Administration costs

Operating profit

Q1

$000

8,966

4,932

4,034

807

2,107

1,120

Current year

Q2

Q3

$000

$000

9,235

9,512

5,080

5,232

4,155

4,280

831

856

2,107

2,107

1,217

1,317

Q4

$000

9,797

5,389

4,408

882

2,107

1,419

Total

$000

37,510

20,633

16,877

3,376

8,428

5,073

Next year

Q1

$000

10,091

5,551

4,540

908

2,107

1,525

Based on the assumptions that cost of sales and distribution costs increase in line with sales and that

administration costs are fixed as in the original budget.

The budget now reflects the rapid growth of the division. Using rolling budgets like this will avoid the problem of

managers trying to control costs using too small a budget and as a result, choking off the growth of the

business. This may explain some of the quality issues that ABC is experiencing.

The rolling budgets will require additional resources as they now have to be done each quarter rather than

annually but the benefits of giving management a clearer picture and more realistic targets more than outweigh

this.

Page | 31

Performance Hierarchy & Budgets

APM – Study Notes

Poor budgeting is probably at the core of the managers' desire to be less controlled. Rolling budgets could be

seen as a tightening of control, so it may also be worth considering changing the style of control being used (see

Hopwood later).

Advantages

Disadvantages

Planning and control will be based on a more

accurate budget