Kotler, Philip Andreasen, Alan R - Strategic Marketing for non-profit Organisations United States Edition-Pearson Education UK (2013)

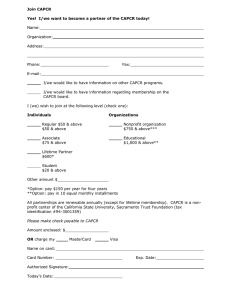

advertisement